이 연구는 환대산업 전공 대학생들의 커리어 탐색 행위에 영향을 미치는 선행요인을 규명하여, 해당 학부커리어 교육의 방향을 제시하고자 시행되었다. 특히 개인적 측면에 초점을 두고, 이 연구는 그들의 자아 존중감이 커리어 탐색 관련 스트레스와 커리어 탐색 행위 자체를 설명하는지를 분석하였다. 아울러, 커리어 탐색 관련 스트레스가 직무탐색 행위에 부정적 또는 긍정적 영향을 미치는지 규명하였다. 마지막으로, 변수들간의 관계가 구조적 모델에서 유의한 관계를 가지는지 실증분석을 하였다. 환대산업을 전공하는 4년제 대학교 학생들을 대상으로 하여, 300부의 설문에서 성실한 277부를 실제 분석에 이용했으며 데이터 분석을 위해 SPSS와 AMOS 20.0을 이용한 구조모형 방정식을 통해 연구가설의 유의성을 측정하였다. 결과에 의하면, 자아 존중감은 커리어 탐색관련 스트레스에 부정적인 영향을 주었고 커리어 탐색 행동에는 긍정적인 영향을 주는 것으로 나타났다. 특히, 셀프 탐색행동은 환경 탐색행동에 비해 자아존중감에 의해 상대적으로 더 영향을 받는 것으로 나타났다. 마지막으로, 탐색 스트레스는 셀프 탐색행동에 부정적인 영향을 주었고, 의사결정 스트레스는 환경 탐색행동에 부정적인 영향을 주었다. 이 결과를 통해, 관련 전공 학부는 커리어 탐색행위에 대한 근본적인 동기 요인을 찾고 학생들이 명료한 목표에 의해 움직일 수 있도록 관련 프로그램 또는 커리큘럼을 적립시켜 나가야 함을 시사하고 있다. 학생들의 커리어 개발 및 동기부여 스킬을 코칭해야 하는 필요성을 제고한다.

Among all the HR issues present in hospitality businesses, employee retention needs to be considered as the hardest issue to be managed (Enz, 2009). Retention issue is significant due to the financial cost of recruiting and retaining employees (Hinkin & Tracey, 2000). For instance, employee turnover could cause emotional costs as well as recruiting and training (Hinkin & Tracy, 2000). Emotional cost explains downward reduction of service quality and employee morale (Hinkin & Tracy, 2000). Hospitality business shows relatively higher costs in both of turnover and emotional issues because hospitality employees are more likely to be influenced by other colleagues (Hinkin & Tracy, 2000) and business productivity can be lowered (Dipietro & Milman, 2004). Thus, investigating the causes of the retention issues and the retention strategies becomes inevitable.

One of the primary factors comes from the candidates' unclear career goals. The more they have clear career goals, the more passionately they explore and acquire the requisite knowledges and/or techniques to accomplish them (Damon, 2008). The deficient knowledge and/or information create unmet expectations between their perception and real career experiences, and this process makes them experience frustration and change career often. To this end, universities and/or colleges which breed up those candidates need to help their students develop career exploration based on long-term career goals. This is one of their primary roles because not only the paradigm of university makes a shift to career focuses but also they are evaluated through the employment rate and the graduates' term of service since hired.

In other words, employment plays an important role for survival of universities and students perceive universities as a main step for their career development. Yoon (2010) also emphasized the university educators’ role to build up their students’ sound work values. Therefore, the universities need to motivate students to explore their own careers and help their career development. As a result, the urgent issues of hospitality businesses are interlinked with those of universities.

In general terms, career exploration has been found to influence on vocational interests (Savickas, 1990) and job satisfaction and attainment (e.g., Werbel, 2000). Moreover, career exploration contributes to the career adaptation of university students (Ahn & Cho, 2012), and that encourages their personal growth (Urakami 1996) and career identity (Robistscheck & Cook, 1999). To this end, the need to investigate the conditions of career exploration is raised.

Within the existing literature, one main stream of research has centered on how the individual motivational variables make an impact on exploratory activities (e.g., Blustein, 1988). In the previous literature, the studies about the relationship between individual motivational factors and the hospitality students' academic performance (e.g., Kim & Byun, 2011) and career exploration (Shim & Lee, 2012) have been developed as well. However, the theoretical assertions upon career factors and individual realms need to be reconfirmed because the vocational issues tend to be disregarded in counseling psychology (Keller, 2006).

In addition, there are few studies to search for the individual motivational factors towards career exploration focused on the specific majors regardless of the raised issues for current educational needs. At the same time, although in the previous literature, self-esteem and anxiety have been frequently examined as the motivational variables towards the college students’ academic and other decision-making behaviors (e.g., Kim, Kim, Cho, & 2002; Chapman, 2006), there are little studies to clarify their influence on career exploration behaviors in a model. As a result, self-esteem and contextual anxiety are likely to be the matters of concern as predictors of career exploration behaviors

Based on the study needs, this study chose self-esteem and contextual anxiety as the predictors of career exploration. Further, researching how anxiety related to career exploration and self-esteem take a part in a student's life can imply significance for university personnel making an effort to encourage students' personal growth (Parisi, 2011).

To this end, it is suggested that there should be renewed studies on the predictors of career exploration behaviors. Hence focused on university students having in hospitality-related majors, who are potential candidates in hospitality business, this study aims to clarify the following goals: 1) investigating whether self-esteem significantly influences contextual anxiety in relation to career exploration; 2) investigating whether the anxiety positively or negatively influences career exploration behavior; 3) presenting the hierarchical relationship among the variables in a structural equation model. Through this study, university personnel may have clear direction of how to conceptualize and treat students' career development.

Self-esteem, commonly developed at a young age, refers to how one perceives about himself or herself. It usually consists of cognitive, behavioral, affective and physical components. It is considered to be the evaluation on a self (Babbio, 2009). Based on the standard of excellence in every society or group, self-evaluation depends on whether he or she fulfills the framework of these particular standards (Rosenberg, 1989). Between the age of 15 and 18, individuals are experiencing a lot of changes and become more care of themselves. Because this is a period of life change, he or she becomes more concerned about his or her own image (Rosenberg, 1989). In a word, self-esteem is a perception about his or her capability and attractiveness from others point of views rather than reality. Noticeably, self-esteem does not reflect a person’s actual attractiveness, and it derives from his or her self-perception (Baumeister, Campbell, Kruenger, & Vohs, 2003). According to previous studies, people are willing to retain their self-esteem because they like to feel positive about themselves based on an intrinsic need.

Self-esteem is influential to people’s overall life like personality, emotions, anxiety, etc. Kowalski & Western (2005) asserted that under a general level of self-esteem, "people have feelings about themselves along specific dimensions, such as morality, physical appearance, and competence" (p245). This helps us to understand those with high self-esteem versus those who don't. Although a person with high self-esteem doesn't need to be good at everything they do, those with high self-esteem are inclined to consider their strength more valuable than those with low self-esteem. They are aware of what they are weak at, and don’t put much weight on it.

Furthermore, high self-esteem is related to psychological well-being while low self-esteem is likely to associate with sadness and depression (Leary, 1999). High self-esteem has also been found to be positively correlated with academic performance because people with high self-esteem may have higher career goals than the ones with low self-esteem (Parisi, 2011). High self-esteem may lead people to have positive level of self confidence to deal with difficult tasks. They are more likely to consistently make an effort regardless of failure while those with low self-esteem may lose self-confidence at the moment of failure (Baumeister et al., 2003).

Finally, school age children’s self-esteem predicts their adulthood’s important performances and overall behaviors (Chung & Yuh, 2009). However, the college students’ self-esteem can be developed through training for communication competency, collective counseling, and wring therapy (Lee, Choi, & Hwang, 2009; Suh, 2009). In other words, self-esteem can be increased among college students if professional training is provided.

2. Contextual Anxiety and the Relationship with Self-Esteem

Anxiety is a “stress-induced emotion that figures in the group-think model” according to Chapman (2006, p1396). In addition, anxiety includes a distressed state in a fear of future insecurity (Chapman, 2006). Contextual anxiety refers to a kind of trait anxiety generated from stress related with a given activity in the context of career decision making and./or exploring behaviors (Stumpf, Colarelli, & Hartman, 1983). This kind of anxiety can influence the process of information seeking (Mittal & Ross, 1998) and decision-making (Baradell & Klein, 1993). In detail, contextual anxiety consists of exploratory and decisional stress (Stumpf et al., 1983). Exploratory stress means to which extent the exploratory behavior for a career stresses a person compared to the other life issues. Similarly, decisional stress means to which extent the decision-making process for a career stresses a person compared to the other life issues.

Researchers have verified a negative relationship between contextual anxiety and the students' self-esteem as follows. The existing studies asserted that self-esteem and stress were interrelated (e.g., Parish, 2011). According to Emil (2003), university students who have higher self-esteem showed lower stressful life events. Additionally, Abouserie (1994)'s study, undergraduate students with high self-esteem are less suppressed by stress than low self-esteem. Further, high self-esteem are unlikely to lower one’s sense of self in the face of stressors, thus looking for intrinsic coping (Guinn & Vincent, 2002). In addition, Park, Bae, & Jung (2002) presented the negatively significant relationship between self-esteem and job exploration. Withdrawn from the previous studies, the relationship between self-esteem and contextual anxiety has been hypothesized, as follows.

3. Career Exploration and the Relationship with Self-Esteem and Contextual Anxiety

3.1. Career Exploration: theory and practice

The theory of career exploration has been extended since the early 1960s, when it was first considered as a concept of general exploratory behavior (Jordaan, 1963). Four different conceptions of career exploration were reviewed by Taveira (1997, 2001). He or she clearly illustrated the evolution of the construct during the several decades as follows.

The first concept, based on Krumboltz's learning theory of learning choice and counseling (Krumboltz, 1979), explains career exploration as an information-seeking behavior or as a career problem-solving behavior. A second concept was originated from career decision-making included the activities of identifying and evaluating options, and seeking information (e.g., Gelatt, 1962). A third concept was in relation with general career development theories considered exploration as a major life stage, that of adolescence (from age 14 to 24). It consisted of the career development behaviors such as collecting, experiencing and implementing an occupational options (Super, 1957). The final concept described exploration as a life-span process to train and develop careers (Taveira, 1997).

In the context of the last position, career exploration has been involving a complex psychological mechanism. For instance, career exploration continues to search for information related and examine self and environment on the basis of clear career goals. In other words, people need to be cognitively and emotionally motivated to interpret and recreate past and current experiences and utilize them for future career to exert the behaviors to exert career exploration. Finally, according to the existing views of the construct, selfand environmental exploration are convinced as two sub-dimensions of the career exploration.

Furthermore, career exploration is different from general exploration in the core goals of exploratory behaviors, and not in the process or condition of that activity. In other words, although someone merely seeks information or examine one’s own past or present experiences, it cannot be assured that he or she is in the process of career exploration. For example, career exploration needs to be conducted through clear goal set up.

As related to this study purpose, the study of career exploration process is considered as one of the main stream of research in the context of career exploration. The contextual and personal dimensions of career exploration are still questioned although they have been studied over the several decades under various perspectives. Under the social learning paradigm, the first studies indicate that individuals more reinforced to information and/or indirect experiences explore careers more frequently (e.g., Krumboltz & Schroeder, 1965).

Other studies suggest that an individual personality also makes a difference on career exploration behaviors (Lazarick, Fishbein, Loiello, & Howard, 1988), pinpointing the importance of external reinforcement in the qualitatively exploratory conditions.

In this context, mostly the studies regarding the motivational theory have suggested that personal factors predict to which extent individuals have career exploration activities. The personal dimension is explained by work role salience, the value of career domain, accomplishment of valued career goals, satisfaction from decision made and usefulness of career exploration (Bluetein & Flum, 1999; Taveira, 2001). In short, it can be said that career exploration is conducted through the value of the career development dimension and through the previous success with career results and the consequent balance between expectation and outcomes.

The studies including self-determination theory by Deci and Ryan (1985) are based on motivation theory as well, and thus suggest that career may be explored though self-determination to some extent (Blustein, 1988). This delivers that career exploration is processed by intrinsic motivation or internalization of extrinsic regulation and this explains the individual variables. Having delineated the elements involved in career exploration models, a motivational factors are revealed self-efficacy (e.g., Creed, Patton, & Prideaux, 2007; Park, 2011), contextual anxiety (Keller, 2006), self-determination, perceived competence, internal locus of control, and self-esteem move towards career exploration intentions and/or behaviors (e.g., Betz & Voyten 1997; Bluestein, 1988, 1989; Solberg, 1998; Taylor & Pompa, 1990).

According to Flum & Bluestein (2000), both individual and environmental variables motivate the exploratory behaviors. Individual factors include self-interest, abilities, other self-related factors while environmental variables include parents' level of education and relationship with important others such as parents, teachers, and friends. Savickas (2002) also indicated the both dimensions explained career exploration behaviors. However, this study focuses on the self-esteem and the contextual anxiety as individual variables. The following review of literature addresses how these factors related to career exploration.

3.2. The Relationship between Self-Esteem and Career Exploration

Students' psychological well-being such as self-esteem and life satisfaction influence their access (participation) to the experiences related to their future employment (Creed et al., 2007). Self-esteem is a perception on self through reflecting how similar a person’s ideal self and real self are. Therefore, self-esteem motivates an individual to make and retain specific goals for themselves (Leary, 1999). For example, adolescent females in a loss of self-esteem experience low academic achievement and loss of career goals (Sadker & Sadker ,1994). In addition, Cho & Ha (2010) asserted that self-esteem, so called psychological characteristic, had a significant and positive impact on career commitment, which explained participation and attachment to career development. Further, Shim & Lee (2011) also proved the positive impact of self-esteem on the hospitality students' career exploration behaviors. Based on the previous studies, the following hypotheses have been drawn.

3.3. The Relationship between Contextual Anxiety and Career Exploration

When concerning the relationship between contextual anxiety and career exploration, there are conflicting theories as to whether anxiety play a positive or negative role for career exploration..

For example, Greenhaus and Sklarew (1981) presented that the people who were less stressed showed active exploration and consequently resulted in positive outcomes. Nichols & Schwartz (1998)’s study also appears to emphasize that the lower level of emotional reactivity towards stress are beneficial when it engages with specific activities.

Further, Kowalski & Westen (2005) depicted that those who have more positive attitude towards a stressor have a resilience of mind than those with a negative attitude. In other words, less stressed individuals from a stressor have more control over their mind. This leads them to the quality of decision making is better than those who are more stressed (Chapman, 2006). Further, in Mittal & Ross (1998)’s study, those in the mood of anxiety tend to process information systematically. On the other hand, the people in a positive emotion are prone to search for information strategically. Those in a positive emotion are likely to be the efficient researchers.

On the other hand, Bluestein and Phillips (1988)’s study on the relationship does have different idea. They stated, "...some forms of contextual anxiety may provide a necessary incentive for individuals to engage in career exploration" (p213). It means that some anxiety about career decision making and exploration moves students towards exploratory behavior. In addition, Bartley (1998)'s study centered on university students suggested that the exploratory stress experienced by male students was likely to result in environmental exploration. Further, the study result added that the both of male and female students stressed by career exploration process are likely to engage in self-exploration. Keller (2006)'s study also indicated career-related stress makes students seek more career information and/or opportunities.

Anxiety associated with career exploration drives a person towards career exploration behaviors through the activation of common defence mechanism, however, defective decision-making could occur (Chapman, 2006). On the other hand, positive emotion associated with a stressor such as career exploration may result in strategic exploration according to Mittal and Ross (1998)’s idea. To this end, the significant influence of contextual anxiety on the college students’ career exploration behaviors can be assumed. However, the direction of the relationship could not be decided based on the literature. As a result, the hypothesis between contextual anxiety and career exploration have been suggested as follows.

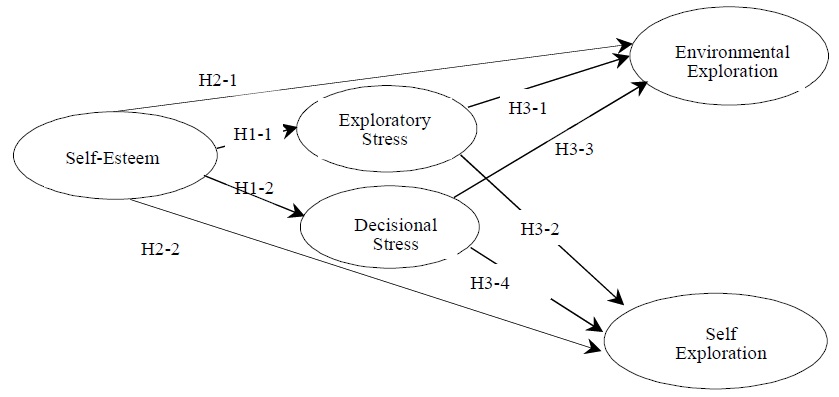

Based on the propositions developed from the literature review, the conceptual model to explain the relations among the hospitality students' self-esteem, exploratory stress, decisional stress, environmental exploration, and self-exploration is illustrated in Figure 1.

1.1. Self-Esteem

Self-esteem defined as a perception about individuals’ capability and attractiveness reflected by others was evaluated through Rosenberg Self-esteem scale (RSE:Rosenberg, 1989). The ten items were used to measure global evaluation of self worth. Participants were asked to rate to which extent they agree with each statement on a five-point scale from "strongly agree" to "strongly disagree".

1.2. Contextual Anxiety

Contextual anxiety refers to a kind of trait anxiety from stress regarding a mandatory activity within the context of decision making or career exploration in this study. Contextual anxiety was measured using the Exploratory Stress (ES) scale and the Decisional Stress (DS) scales of the Career Exploration Survey (CES; Stumpf, Colarelli, & Hartmen, 1983). The ES scale include three items and the DS scale have five items. The Participants compared career-related stress with other stresses related to important life issues. Answers were put on a 5-point Likert scale from “insignificant compared to other issues with which I have had to contend” to "one of the most stressful issue with which I have had to contend." Based on Stumpf et al. (1983)’s scale, modified items by Keller (2006) was used since he or she adjusted wording so as to apply to university sample.

1.3. Career Exploration

Career exploration is a long term process to train and upgrade careers through overall life and include exploration on self and environment. The dimensions of Environmental Exploration (EE) and Self Exploration(SE) scales were measured employing Exploration Survey (CES; Stumpf et al., 1983). Participants rated how much they were enrolled in career exploration activities over the previous three months. Environmental exploration consists of six items and self exploration consist of five items. Items were measured based on a five-point Likert scale raging from “little” to “a tremendous amount.”

The people targeted for this study are university students majoring in hospitality related management. First of all, draft survey questionnaires had been drawn after translating the questionnaire in English to Korean. In addition, hospitality students of K university in Seoul and D university in Daegu were identified to conduct preliminary survey to presume the validity of the structural model. In preliminary survey, the researcher mailed draft questionnaires to a total of 50 students. Moreover, the respondents were recommended to pinpoint any inadequate and/or unclear items. This preliminary survey has been executed from September 15th to 30th in 2012.

To conduct a main survey, a convenience sample of universities which have department of hospitality in Korea were surveyed; K1, K2 and S universities in Seoul, D1, D2, Y and G universities in Daegu, and D and P universities in Pusan. Further, a mail survey was employed to carry out the survey after each department professor's approval had been given. The main survey was conducted from October 15th to November 25th in 2012. A total of 315 responses were received out of the 400 cases. Cases with missing value were subsequently dropped from the analysis and 277 faithful cases have been analyzed.

The collected data was analyzed employing the SPSS and AMOS 20 software program. Descriptive statistics, multi-variate analysis of variance, and structural equation modeling (SEM) were utilized. Frequency analysis, reliability analysis after using Cronbach's alpha, and confirmatory factor analysis were operated. Further, the correlation analysis was conducted to verify the reciprocal relationship among the variables. To verify the hypotheses and model of the study, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to examine conformity of the causal relationship among each factor and covariance structure analysis was used to investigate a path coefficient.

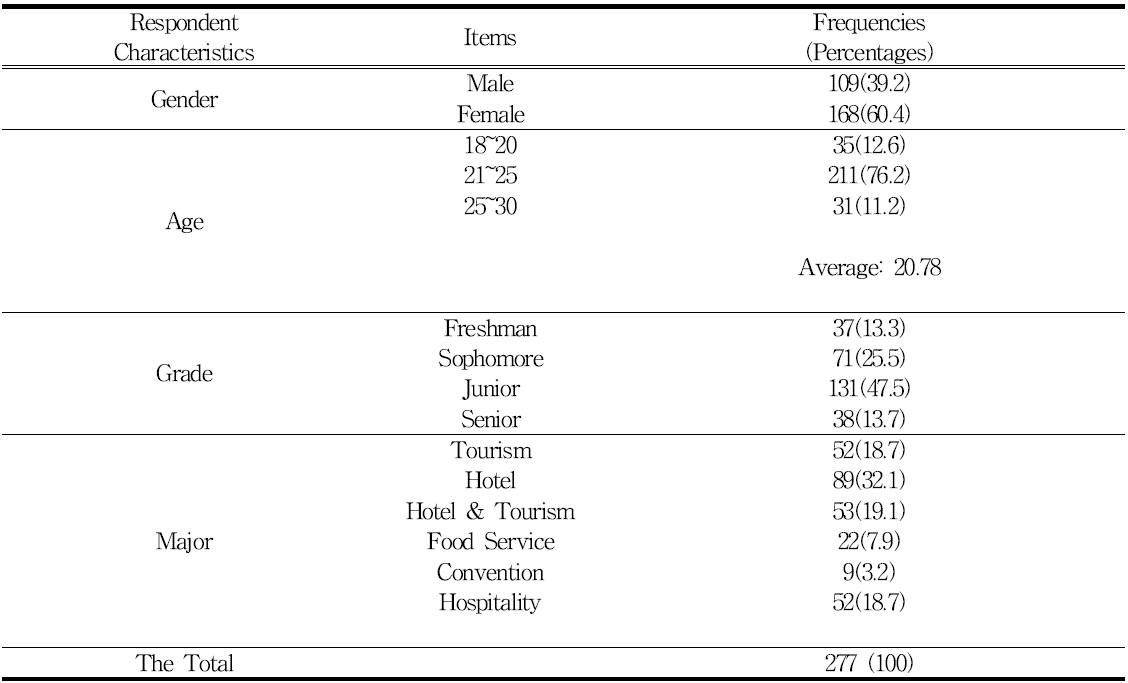

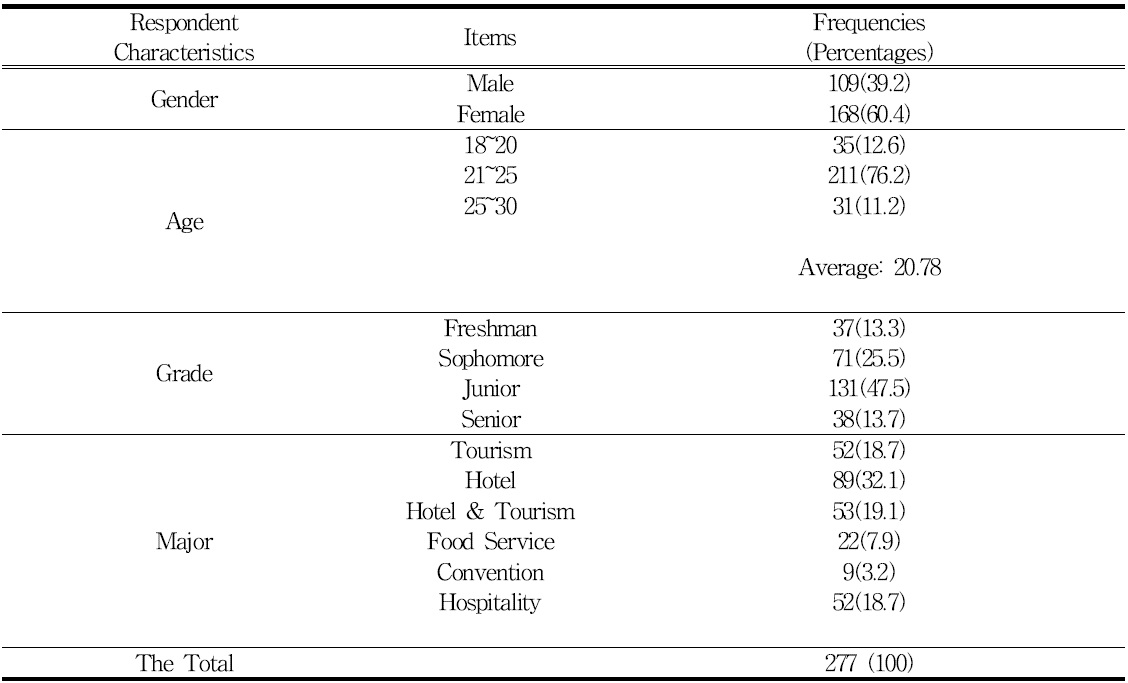

As presented in Result of the demographic analysis of the respondents

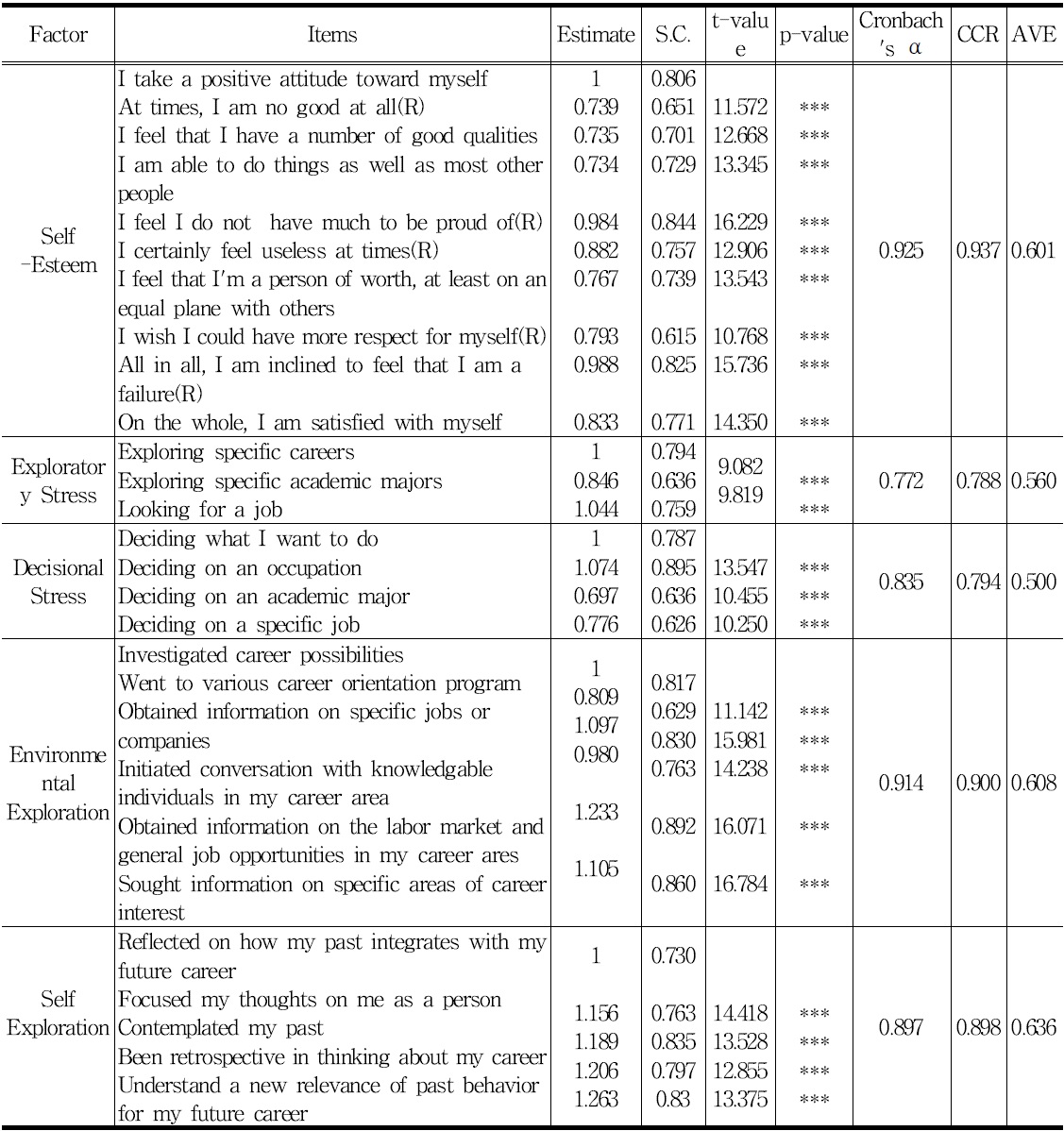

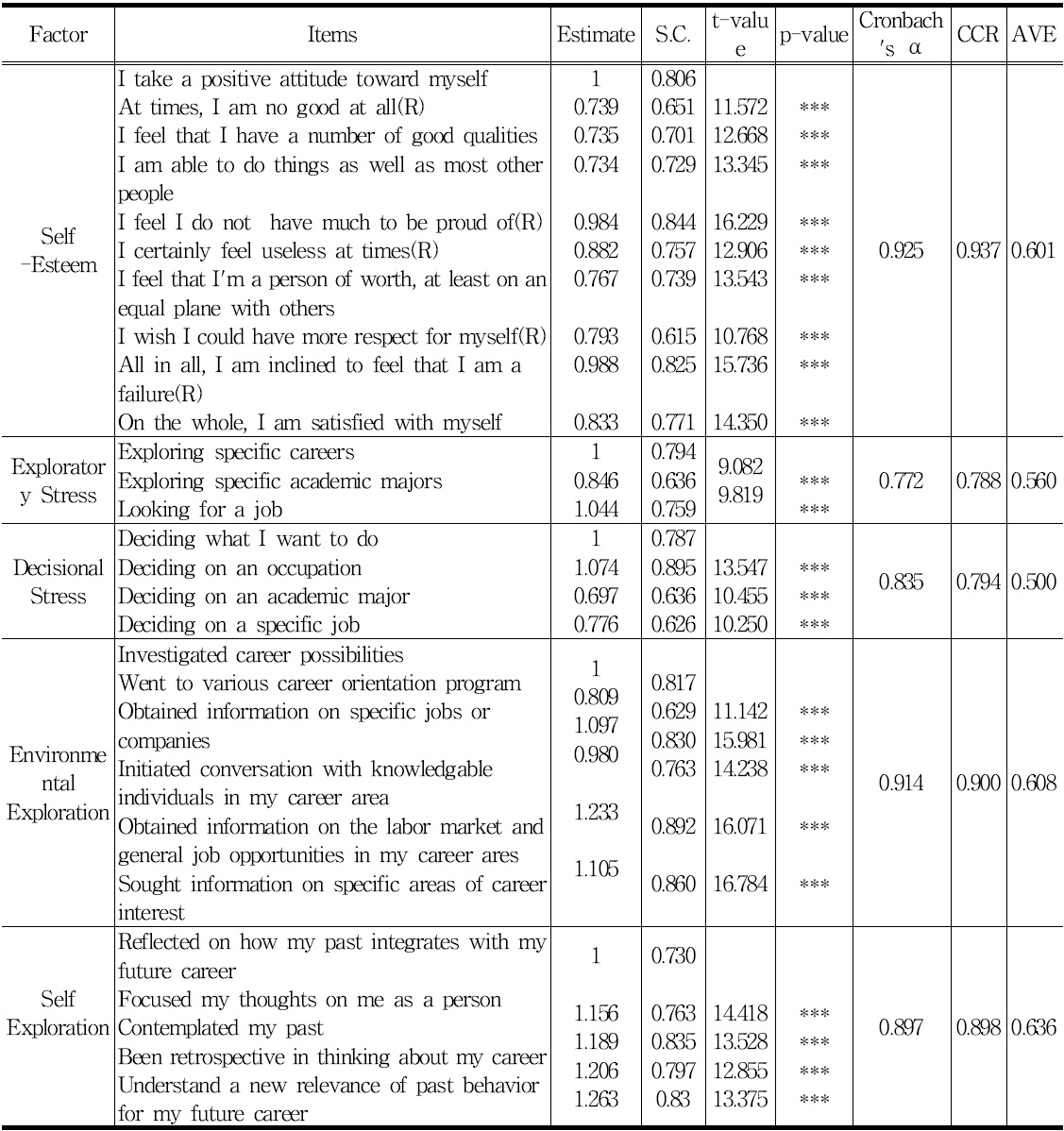

2.1. Results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The confirmatory measurement model was assessed to evaluate the construct validity of the measurement used in this study. As noted by Noar (2003), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) procedures can provide confirmation that psychometric properties a scale are satisfactory that extend beyond exploratory analytic technique. It was noted that CFA can add further information about dimensionality of scale by testing a variety of models against one another (Noar, 2003). In this study, the confirmatory factor analysis was completed with maximum likelihood estimation. CFA was applied to all the items and chi-square of 502.09, degree of freedom of 331, and p-value of 0.000(p<0.001). Further, the value in chi-square/df should be less than three to secure overall goodness of fit (Kim, 2007). The value of chi-square/df shows 1.517 so that overall goodness of fit is identified. In assessing model fit, the following indices were employees: GFI (Goodness-of-fit index: desirable at ≧ 0.90), AGFI (Adjusted Goodness of fit Index: desirable at ≧0.90), RMR (Root Mean Square Residual: desirable at ≦0.05), NFI (Normed fit index: desirable at ≧0.90), CFI (Comparative fit index: desirable at ≧0.90), x2 (chi-square: desirable at >0.05), TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index: desirable at ≧0.90), RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation: desirable at < 0.05). As presented in Confirmatory factor analysis and reliability analysis Further,

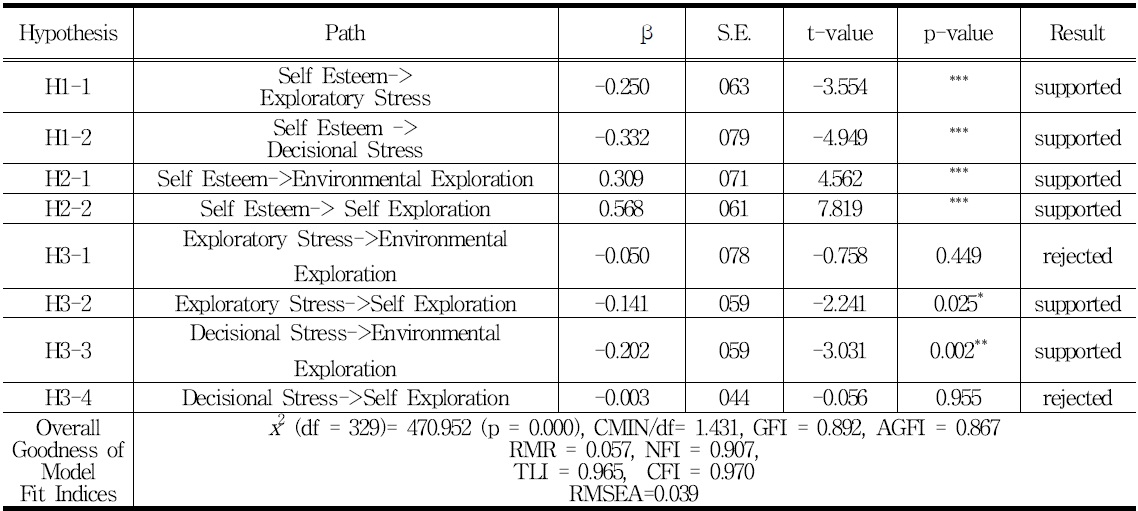

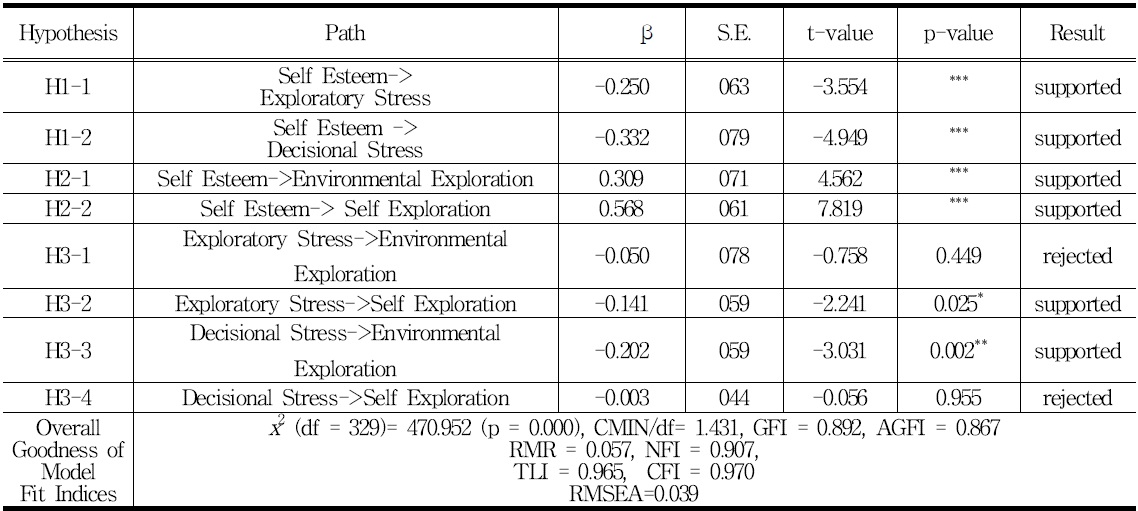

2.2. Results of Validity and Reliability

As the survey items are adapted from different streams of studies, it is important to ensure construct reliability and validity. Cronbach's coefficient alpha was calculated to determine reliability of the measurement. As indicated in Measurement model Discriminant validity was established using the procedures outlined by Fornell and Larcker (1981). Preceding verification of theoretical model showed some fit indices such as GFI and AGFI were not fulfilled and therefore, covariance was conducted using modification indice(MI) so as to improve goodness of fit. This is based on Hooper, Joseph, & Mullen (2008)'s suggestion of "Allowing modification indices to drive the process is a dangerous game, however, some modifications can be made locally that can substantially improve results"(p 56). Parameter estimates in structural model As shown in Secondly, results suggest that hospitality majored students' self-esteem significantly influences environmental exploration (β = 0.309, p<0.001) and self exploration (β = 0.568, p<0.001). That is, the students who have higher self-esteem tend to look for career opportunities and reflect themselves to fit into specific careers. Therefore, the hypotheses 2-1 and 2-2 were supported. That is, the hypothetical impact of self-esteem on career exploration was fulfilled. Finally, results indicate that hospitality majored students' exploratory stress does not have any significant impact on their environmental exploration while it significantly influences their self exploration behavior (β = -0.141, p<0.05). At the same time, decisional stress is a negative predictor of environmental exploration (β = -0.202, p<0.01), while it is not a significant predictor of self exploration. Therefore, hypotheses 3-1 and 3-4 were rejected while the hypotheses 3-2 and 3-3 were supported. As a result, the contextual anxiety has a partially negative impact on career . This means, the students with positive emotion about career exploration have more research on career opportunities and self examination to some extent. In the hypotheses setting, the positive or negative direction was not decided due to the possible outcomes of both directions based on the existing literature. This study result supports the negative relationship between the contextual anxiety and career exploration. This study presented and tested a structural model depicting the relationship among self-esteem, contextual anxiety, and career exploration behavior focused on hospitality students. The results are discussed as follows. Firstly, the structural analysis found path coefficient of -0.250 for the impact of self-esteem on exploratory stress and –0.332 for the impact of self-esteem on decisional stress. The influence of self-esteem on decisional stress is relatively higher than the one on exploratory stress. The current findings were consistent with previous research. For example, Guinn & Vincent (2002) and Emils (2003) also found a significantly negative relationship between high self-esteem and status of anxiety or stress. These results underlie that the hospitality students’ self-esteem help them to regulate their anxiety towards career-related stress. At the same time, the students who have higher self-esteem are willing to explore career information with lower stress. Secondly, the significant influence of self-esteem on self exploration(the path coefficient of 0.568) is relatively higher than the significance of self-esteem on environmental exploration (path coefficient of 0.309). This results follow the notion of Creed et al. (2003), who suggested that self-esteem, a condition of the psychological well-being lead to the active career related experiences. Noticeably, hospitality students seem more interested in self-exploration than environmental exploration on the basis of their self-esteem. In other words, the interest in self put more weight on self-oriented exploration than environment-oriented exploration. Finally, the negative impact of exploratory stress on self exploration has been found to have path coefficient of – 0.141 while it does not make any significant impact on environmental exploration. Furthermore, decisional stress makes a negative influence on environmental exploration with path coefficient of –0.202 while it does not significantly influence self exploration. This result is consistent with Greenhaus and Sklarew (1981) who presented that contextural anxiety related to career exploration functioned as a hinderance to career exploration behaviors. On the other hand, the results are inconsistent with Bartely (1988) and Keller (2006) who demonstrated that the moderate levels of stress motivate the students to explore career development. That is, the hospitality students seem to explore their own interest more actively, when they are in psychologically positive condition toward career exploration rather than anxious status. There are several theoretical and practical implications for university practitioners. Those who ever explored their careers are likely to be satisfied with their jobs. At this point, this study provides insight into human resources issues of turnover and/or job dissatisfaction. The hospitality students are employed in the various industries. For example, the hospitality majored students enter management and other office work (32.1% of the graduates), financial business (20.4% of the graduates), sales and marketing (11.7% of the graduates), hospitality business (11.4% of the graduates) (Statistical Data of Korea Culture and Tourism Institute, 2013). This implies that any other industries as well as hospitality industries need to keep an eye on whether the applicants have high self-esteem in relation with career exploration. Together with this, university practitioners play important part to motivate and reinforce their career development. Also, in previous studies, the relationship between anxiety and career exploration was unclear. For example, the positive results by Keller (2006) and Blustein & Phillips (1988) are disparate to Greenhouse and Sklarew (1981)’s negative relationship. This study adds the negative relationship to the existing literature. It is important to notice that the scholars who addressed the positive relationship even emphasized the anxiety management. Otherwise, individuals may have distorted information acquired during exploration activities. In other words, some degree of anxiety may initiate exploration behavior, however the emotional response, need to be regulated to have satisfactory outcomes. Further, high self-esteem, positive attitude toward self is a part of psychological well-being. As mentioned above, self-esteem can be raised in college level through training for communication competency, collective counseling, and writing therapy (Lee, et al., 2009; Suh, 2009). Psychological well-being can be also acquired through physical condition, mind set, and spirit. In other words, to approach self-esteem university practitioners or counselors need to provide the students with training their body and mind as well. For example, department of hospitality administration of K university in Seoul has already undertaken so called 'self-management' subject so as to implant sense of purpose to their students. For example, the professor, who teach this subject, said that a balance of body and mind had a connection to self-esteem (dr. YJ Kwon, personal interview, May 15th, 2013). This says that, simply informing them raising self-esteem and lowering stress does not help them alter their attitude toward self and environment. They need to have some opportunity to realize their values and the consecutive confidence. Thus, they may be motivated to navigate opportunities. In addition, those who are overwhelmed by anxiety and stress experience difficulty in distinguishing thoughts from emotions, and thus they tend to respond to emotion rather than regulating the process (Nichols & Schwartz, 1998). Actually, the most of adolescents exposed to the need to find a career must experience these stressful processes (Keller, 2006). To this end, the hospitality students who perceive career related-anxiety are likely to react to the anxiety or emotional experience. To some extent, they are aware of the need of career exploration and may have exploratory behaviors. However, they may not effectively conduct the tasks since they are possibly inclined to decrease the level of anxiety temporarily rather than enter the real exploration. On the other hand, those who do not take stress emotionally better understand themselves and engage in exploration behavior effectively. Hence, the university personnel need to look for how to relieve anxiety effectively and separate thoughts from feelings. For example, cognitive change could be one of the strategies to separate thought from emotions since it emphasizes the interpretation of the situation (Scherer, Schorr, & Johnstone, 2001). Emotion regulation could be one of the strategies. It means how we control our emotional choice, period, and the way of experience and expression (Gross, 2007). According to Gross (2007), individuals need to select either avoidance or confrontation through analysis of the context. In other words, the hospitality students need to be directed to confront the situation or avoid it depending on how important the anxiety is for their lives. In addition, the students can be advised to withdraw attention by closing the eyes and redirect attention through a shift of internal focus (Gross, 2007). That is, if the hospitality students are trained to cognize the situation in more positive way, their anxiety may not lead to emotional pressure. Finally, emotion regulation can be processed through direct control of physiological and behavioral responses (Gross, 2002). For example, exercise and relaxation may be helpful to minimize the negative physiological and behavioral dimensions because as body, mind, and spirit are interrelated. as mentioned above. As a result, these activities can be conducted via specific lecture and/or programs.

There are several limitations to be addressed. First of all, self-report was used to all measures, and therefore it might influence the study results since people tend to evaluate themselves in socially desirable way although it is confidential (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). In other words, the practical difference among the respondents’ level of self-esteem and career exploration may be overlooked in spite of the possible difference if it is measured from others' perspectives instead of self-report. Secondly, both individual and relational variables need to be addressed in overall models of exploratory behaviors (Flum & Bluestein, 2000), however, this study only included individual variables as the predictors of exploratory behaviors. Finally, non-response bias may influence the results due to fairly high level of non-response rate. Bias is calculated with non-response rate and the difference between the respondent and non-respondent answers (Ritz, 2009). Researchers need to make their attention on reducing the non-response rate to minimize bias, since it is often impractical to design a survey to influence the difference between the respondent and non-respondent answers (Ritz, 2009). Future studies can reduce non-response rate through having personal and professional introduction, short survey length, clear wording, sending reminding e-mails to non-respondents, and so on. Future studies to be developed for career exploration are suggested as follows. First, future studies can choose the variables of one’s emotional response and effective career exploration behavior in their models. In other words, emotional response is more actually experienced than contextual anxiety merely measured through cognitive judgement. Thus, this study may complement the limit of perceived stress itself. At the same time, effectiveness of career exploration could be measured through satisfaction on career exploration because quantity of exploration does not necessarily associate with effective exploration. In addition, the different perspective of male and females need to be further addressed, and thus future studies need to find the unidentified variables that are specific to career exploration for female and/or male students. Finally, individual and environmental variables need to be addressed altogether in future studies. For example, they can include individual variables related to individual traits and environmental variables originated from social dimensions. Although there are several studies investigating both dimensions (e.g., Keller, 2006), future studies need to look for further variables and suggest practical implications., 39.2 % of respondents were males, and 60.4% of them were females. It reflects that mainly females are majored in hospitality management. All the respondents are in twenties and average age is 20.78. Moreover, freshmen consist of 37 people (13.3%); sophomores consist of 71 people (25.5%); juniors consist of 131 students (47.5); seniors consist of 38 people (13.7%). Finally, their current majors were as follows; tourism management (18.7%), hotel management (32.1%), hotel and tourism management (19.1%), food service management (7.9%), convention management (3.2%) and hospitality management (18.7%).

] Result of the demographic analysis of the respondents

2. Analysis of Validity and Reliability

, GFI (0.888) and AGFI (0.862) indicate unfulfilled indices, however, RMR (0.050), NFI (0.900) CFI (0.963), TLI (0.963), and RMSEA (0.043) indicate the reasonable fits of the data. The relatively small sample sizes limit the possibility of reaching the 0.9 cutoff value for the two fit indices and they are not dependable as "a stand alone index " (Hooper, Joseph & Mullen, 2008, p54). Further, a strict adherence to suggested cutoff values can result in the improper rejection of an acceptable model (Marsh, Hau, & Wen, 2004). Therefore, the relationship among the latent variables can be presumed with the reasonable fits of the data.

] Confirmatory factor analysis and reliability analysis

presents standard estimates for a measurement model. As illustrated, factor loading of all measures were moderate (ranging from 0.615 to 0.892). The factor loadings showed that relevant measurement items performed moderately well in reflecting the designated underlying construct.

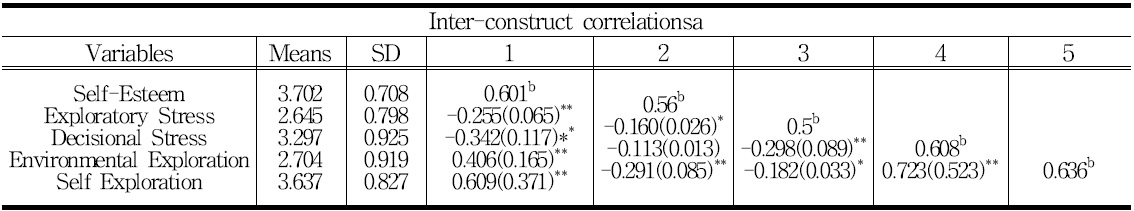

, Cronbach's a of each construct in measurement model is ranged from 0.772 to 0.925, significantly a scale with high level of reliability; this value is adequate at Cronbach's a >0.60 (Lee, 2009). If construct reliability reaches above 0.7, convergent validity or internal consistency is secured 2007). Also, convergent validity is procured as long as AVE reaches above 0.5 (Kim, 2007). In terms of construct reliability, the values of five constructs are ranged from 0.788 to 0.937. At the same time, as illustrated in

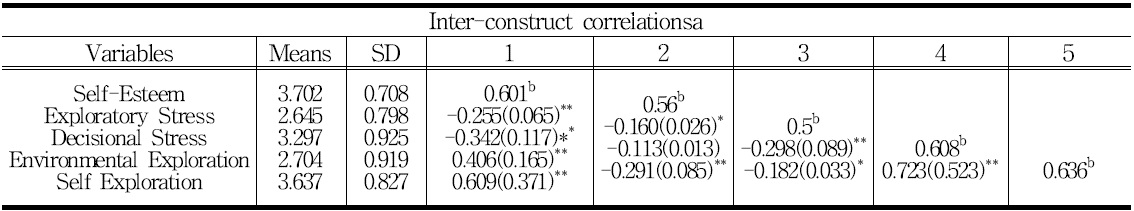

, factor loading of each variable is above 0.615, showing a moderate to high construct validity. Further, each average variance extracted (AVE) reaches between 0.500 to 0.636.

] Measurement model

shows the correlations between the latent variables and the average variance extracted (AVE) of each construct. Fornell and Larcker (1981) prescribe that the squared correlation between constructs must be less than the AVE of each underlying construct in order for the constructs to have discriminant validity. As suggested in

, the squared correlations between two constructs are ranged lower than each AVE. These outcomes established discriminant validity. As a result, these values represent all five constructs and it is significant to analyze the relationship between those constructs.

illustrated the strength of the relationships among the constructs, showing path coefficients and overall goodness of model fit indices. Overall, the model was acceptable fit; (x2: df =329)= 470.952 (p = 0.000), GFI = 0.892, AGFI = 0.867, RMR = 0.057, NFI = 0.912, TLI = 0.965, CFI = 0.970, RMSEA=0.039.

] Parameter estimates in structural model

, the postulated hypotheses were examined through investigating the path coefficients of the constructs in the final model. Firstly, the results indicate that exploratory stress (β = - 0.250, p<0.001) and decisional stress (β = - 0.332, p<0.001) were significantly predicted by hospitality majored student's self-esteem. In other words, the students' self-esteem drives them to less stress about exploration and decisional activities. Specifically, the negative impact of students' self-esteem on decisional stress is higher than the impact on exploratory stress. Therefore, hypotheses 1-1 and 1-2 were supported. Overall, the hypothesis 1 for the relationship between self-esteem and contextual anxiety was supported.

2. Limitations and Future Research

참고문헌

34.

Kim G. J, Byun G. I.

(2011)

The effect of learning motivation and self-control learning ability of college students majoring in hotel and food service on academic achievement: Focusing on comparison between junior colleges and senior colleges in Daegu & Gyeongbuk.

[Korean Journal of Hospitality Administration]

Vol.20 P.207-226

59.

Shim J. Y., Lee H. R.

(2012)

A Study of relationship between self-leadership and career exploration behavior in students majoring airline service, hospitality, tourism, food service management: Focused on the mediating effect of self-Esteem.

[Korean Journal of Hospitality Administration]

Vol.21 P.231-251

59.

Shim J. Y., Lee H. R.

(2012)

A Study of relationship between self-leadership and career exploration behavior in students majoring airline service, hospitality, tourism, food service management: Focused on the mediating effect of self-Esteem.

[Korean Journal of Hospitality Administration]

Vol.21 P.231-251

61.

(2013)

이미지 / 테이블

61.

(2013)

이미지 / 테이블

[

<Figure 1>

]

Proposed Research Model

[

<Table 1>

]

Result of the demographic analysis of the respondents

[

<Table 1>

]

Result of the demographic analysis of the respondents

[

<Table 2>

]

Confirmatory factor analysis and reliability analysis

[

<Table 2>

]

Confirmatory factor analysis and reliability analysis

[

<Table 3>

]

Measurement model

[

<Table 3>

]

Measurement model

[

<Table 4>

]

Parameter estimates in structural model

[

<Table 4>

]

Parameter estimates in structural model