>

Social Capital and Parental Financial Preparation

To pay for their children’s college education, parents may adopt various financial strategies ranging from reducing expenses or working extra hours to setting up a college investment such as a mutual fund account. Obviously, these various financial strategies largely depend on the availability of economic resources (Steelman and Powell 1991). However, social capital may complement limited economic resources and play an important role in college persistence owing to its potential capacity to provide easy access to information and knowledge about college costs and academic life. Grodsky and Jones (2007) suggest that inequalities in the knowledge of college costs contribute to a pattern of postsecondary attendance stratified by socioeconomic background, finding that socioeconomically disadvantaged parents are less likely to provide estimates of college tuition costs and, when they do so, tend to have greater margins of error.

Low-income students have very different perceptions of information about financial aid and college opportunity compared to their more affluent counterparts (Choy 2001; U.S. Department of Education 2000). Low-income parents are also more likely than middle-income parents to lack information and knowledge about financial aid. Roderick

We believe that the degree to which children are financially prepared for college may be constrained by the information available to them, which in turn depends on the social capital of their parents. We attempt to link parental financial preparation with social capital and examine whether these two factors have a critical impact on children’s college completion. Parents who are committed to financing their children’s college education but are financially constrained are likely to gather information about college costs in advance. As part of this process, parents’ discussions with other parents as social capital may play an important role in determining whether appropriate action is taken. In addition, parents’ discussions with their children as another form of social capital frequently used in past education research may play an important role in parental financial preparation and children’s college completion.

>

Financial Preparation and College Experiences

Although various factors including students’ academic ability and the institutional environment affect persistence in postsecondary education (Tinto 1993), financial preparation appears to be playing an increasingly important role in college persistence. This is because college costs in the United States have dramatically increased over the past decade. The average cost of tuition, room and board at one of the nation’s four-year public colleges and universities for an entire academic year (2005-06) is approximately $13,000 for in-state students and more than $36,000 for out-of-state students (U.S. Census Bureau 2007), both of which are more than double the corresponding figures for 1990. A variety of funding sources such as student loans have also become increasingly available to tertiary students, but parents remain the primary source of support for adolescents in postsecondary education (Bozick 2007; Steelman and Powell 1991).

In a study of three cohorts of high school seniors (1972, 1982, and 1992), for example, Turley

Indeed, prior studies show that perceived college education costs affect students’ decisions on when (e.g., straight after high school graduation or somewhat later) (Bozick and Deluca 2005) and where (e.g., a two-year vs. four-year college) they begin their postsecondary education (Kim and Schneider 2005). In addition, costs actually incurred during their college years tend to affect the continuity of studies among students (Goldrick-Rab 2006). To cover educational expenses by themselves, many college students choose to work full-time or parttime; 37 percent of undergraduates were enrolled part-time in the fall of 2004 (U.S. Department of Education 2006). Working full-time or part-time often interferes with school work and tends to extend the time students take to complete their programs, or may increase the likelihood of eventually dropping out of college (Chen 2007; U.S. Department of Education 2002). As such, the degree to which financial resources are available within the family greatly shapes a variety of college experiences of children.

However, we believe that regardless of the availability of financial resources within the family and the type of financial strategy parents employ, parents’ sacrifices and efforts to support their children’s education can lead their children to have a stronger “sense of familial responsibility that transcends not only familial duty but the will to succeed” (Byun

1The U.S. Census Bureau 2007 data show that people with a B.A. earn $54,689 on average annually, compared to $29,448 for those with a high school diploma.

We used the NELS:1988/2000 data for which the National Center of Education Statistics (NCES) drew random samples of approximately 25 eighth- graders in about 1,000 randomly selected schools in 1988. NELS:1988/2000 followed these students through high school in 1990 and 1992, and beyond in 1994 and 2000 (at age 26 or 27), and consisted of approximately 12,100 students. Of these, if students who reported enrollment in postsecondary institutions in one of the last two follow-ups (i.e., 1994 and 2000), their postsecondary transcripts were requested from institutions they attended (approximately 9,600) (U.S. Department of Education 2003).

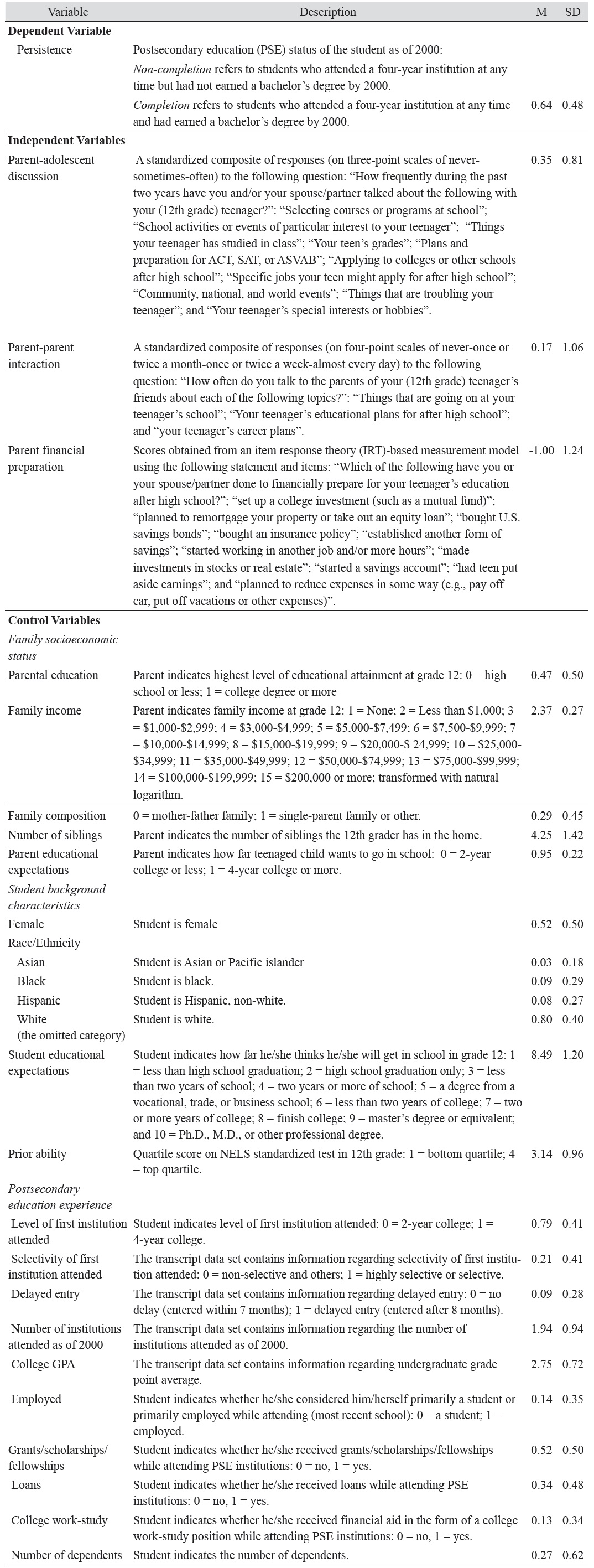

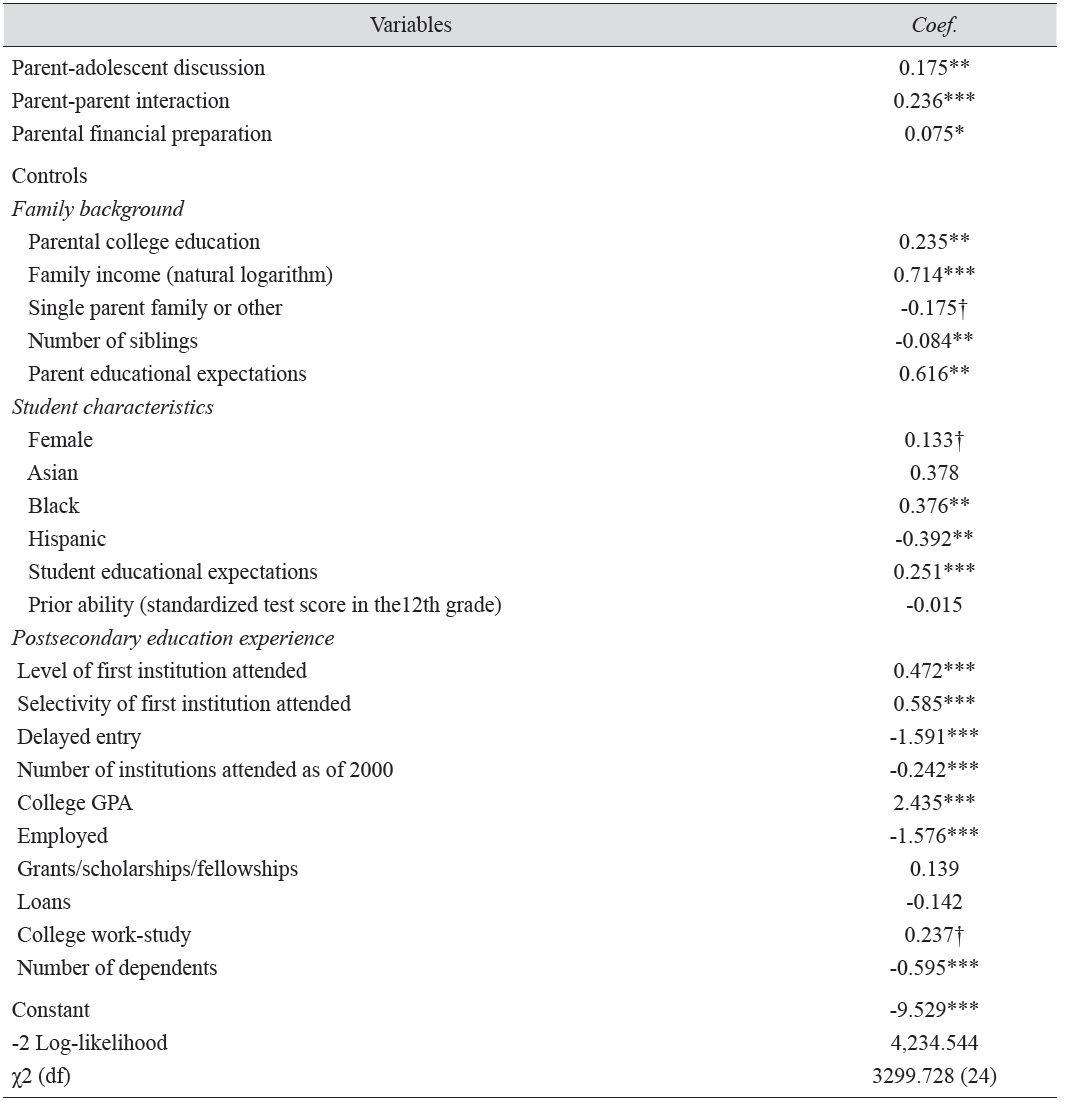

We restricted our analytic sample to the NELS students who attended a four-year institution at any time before 2000 and whose high school and postsecondary transcript data were available. Due to small sample sizes, we excluded American Indian/Alaska Native and multiracial students, resulting in a total sample of 5,780.2 Of these, approximately 64 percent earned a bachelor’s degree by 2000 (see Table 1). In other words, only about six out of ten NELS students enrolled in a four-year postsecondary institution had completed their four-year college within eight years of graduating from high school.

[Table 1.] Descriptions of Variables

Descriptions of Variables

It is important to note that although there are more recent survey data that follow U.S. high school students through college than the NELS:1998/2000, the NELS:1988/2000 data were the most appropriate for our study because they offer postsecondary transcript information. In other words, the High School Longitudinal Study of 2009 has followed the most recent cohort of high school students but its second follow-up data (2012) were not available when the current study was conducted. The Education Longitudinal Study of 2002 has also followed a more recent cohort of high school students into the postsecondary years than the NELS:1988/2000, but again its postsecondary transcript data were not available either when the current study was conducted. Yet we acknowledge that NELS:1988/2000 may reflect neither contemporary U.S. high school students nor recent trends in U.S. higher education.

Social capital

In the literature, the operationalization of social capital varies across studies. In this study, among others, we were interested in two types of social capital: (1) parent-adolescent discussion and (2) parent-parent (of teenager’s friend) interaction. Parent-adolescent discussion was measured by using a standardized composite (i.e., M = 0, SD = 1) of responses (on threepoint scales of never-sometimes-often) to the following question: “How frequently during the past two years have you and/or your spouse/partner talked about the following with your (12th grade) teenager?”; (a) “Selecting courses or programs at school,” (b) “School activities or events of particular interest to your teenager,” (c) “Things your teenager has studied in class,” (d) “Your teen’s grades,” (e) “Plans and preparation for ACT, SAT, or ASVAB,” (f) “Applying to colleges or other schools after high school,” (g) “Specific jobs your teen might apply for after high school,” (h) “Community, national, and world events,” (i) “Things that are troubling your teenager,” and (j) “Your teenager’s special interests or hobbies.” Parent-parent interaction was also measured by using a standardized composite (i.e., M = 0, SD = 1) of responses (on four-point scales of never-once or twice a month-once or twice a week-almost every day) to the following question: “How often do you talk to the parents of your (12th grade) teenager’s friends about each of the following topics?”; (a) “Things that are going on at your teenager’s school,” (b) “Your teenager’s educational plans for after high school,” and (c) “your teenager’s career plans.”

Parental financial preparation

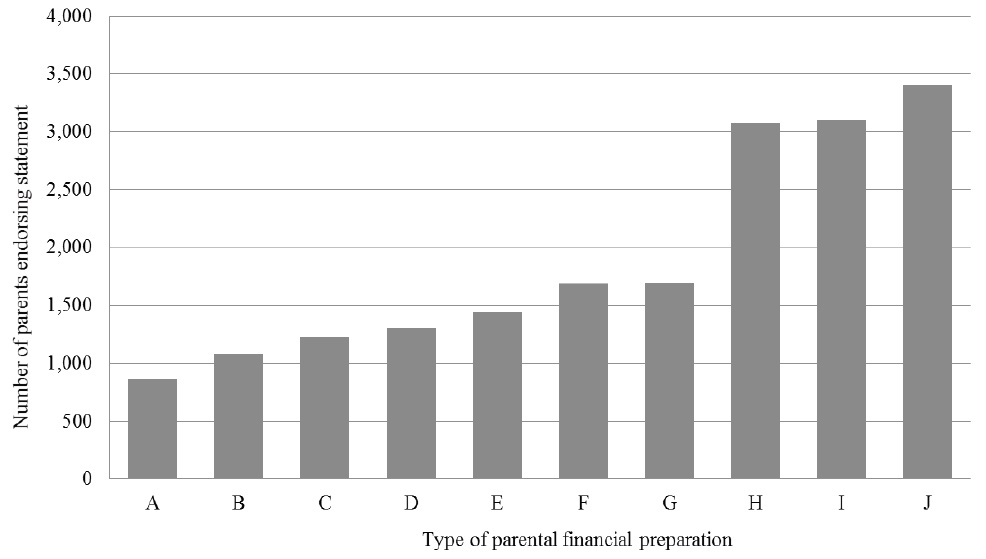

To measure the extent to which parents had financially prepared for their adolescents’ postsecondary education by the time their adolescent graduated from high school, we obtained a composite score by employing an item-response theory (IRT)-based measurement model that uses the following dichotomous yes-no questions and responses: “Which of the following have you or your spouse/partner done to financially prepare for your teenager’s education after high school?”; (a) “set up a college investment (such as a mutual fund),” (b) “planned to remortgage your property or take out an equity loan,” (c) “bought U.S. savings bonds,” (d) “bought an insurance policy,”; (e) “established another form of savings,” (f) “started working in another job and/or more hours,” (g) “made investments in stocks or real estate,” (h) “started a savings account,” (i) “had teen put aside earnings,” and (j) “planned to reduce expenses in some way (e.g., pay off car, put off vacations or other expenses)”.

We chose the IRT measurement model over classical psychometric approaches (e.g., principal factor analysis) because IRT models provide better definitions of the underlying construct, item scales and incremental information (Cella and Chang 2000), as well as more robust item statistics that are independent and invariant over sample populations that vary in the trait measured by the test (Dapueto

Figure 1 shows parents’ endorsement rates for the ten items listed above. The results suggested that item A (set up a college investment) was the most difficult option (i.e., few parents choose to financially prepare for their adolescent’s postsecondary education), whereas item J (planned to reduce expenses in some way) was the most straightforward one and was chosen by most parents.

College completion status

The dependent variable was college status and included two states: non-completion and completion. Non-completion refers to students who attended a postsecondary institution at any time after graduating from high school but had not earned a bachelor’s degree by 2000. Completion refers to students who attended a postsecondary institution at any time after graduating from high school and earned a bachelor’s degree by 2000. To identify students’ college completion status more accurately, we used postsecondary transcription data collected as part of the NELS.

Controls

For the control variables, we included a variety of family background variables, individual factors and postsecondary experience variables. For family background, we included (1) parental education; (2) family income; (3) family composition; (4) family size; and (5) parents’ expectation for their adolescent’s attainment of a four-year college degree (vs. a two-year college degree). For student characteristic variables, we included (1) gender; (2) race/ethnicity; (3) educational expectations; and (4) prior ability. Finally, for adolescents’ postsecondary education experience, we included(1) the level of the first institution attended; (2) the selectivity of the first institution attended; (3) delayed entry; (4) number of institutions attended as of 2000; (5) average college GPA; (6) whether the subject considered him/herself to be primarily a student (= 0) or primarily employed (= 1) while attending postsecondary institutions; (7) each of the following types of financial aid received: (a) grants/scholarships/fellowships, (b) loans, and (c) college work-study positions (measured by a dichotomous variable (yes = 1 vs. no = 0); and (8) number of dependents as of 2000. Table 1 outlines the variables included in our analyses.

We first performed descriptive statistics for the variables included in our analyses. We also examined differences in selected family background indicators, student characteristics, and postsecondary experiences between students who completed a four-year degree and those who did not. We next examined whether social capital was related to parental financial preparation using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. Note that for this OLS regression analysis, we controlled only for family background and student characteristics but not for college experiences. We then conducted logistic regression analysis to estimate the effects of social capital and parental financial preparation on college completion among adolescents with other variables held constant. Finally, based on our expectation that parental financial preparation would have a greater impact for adolescents from low-income families than for their counterparts from high-income families, we tested whether the effect of this factor on college completion among adolescents differed according to the level of family income (by dividing the sample into two groups based on whether family income exceeds the sample mean household income level of $45,000).

Because listwise deletion results in a considerable loss of data, we used multiple imputation 58 Korean Journal of Sociology techniques to replace missing values through an alternative algorithm suggested by King

2Sample sizes throughout the article are rounded to the nearest 10 in compliance with NCES regulations for using restricted data.

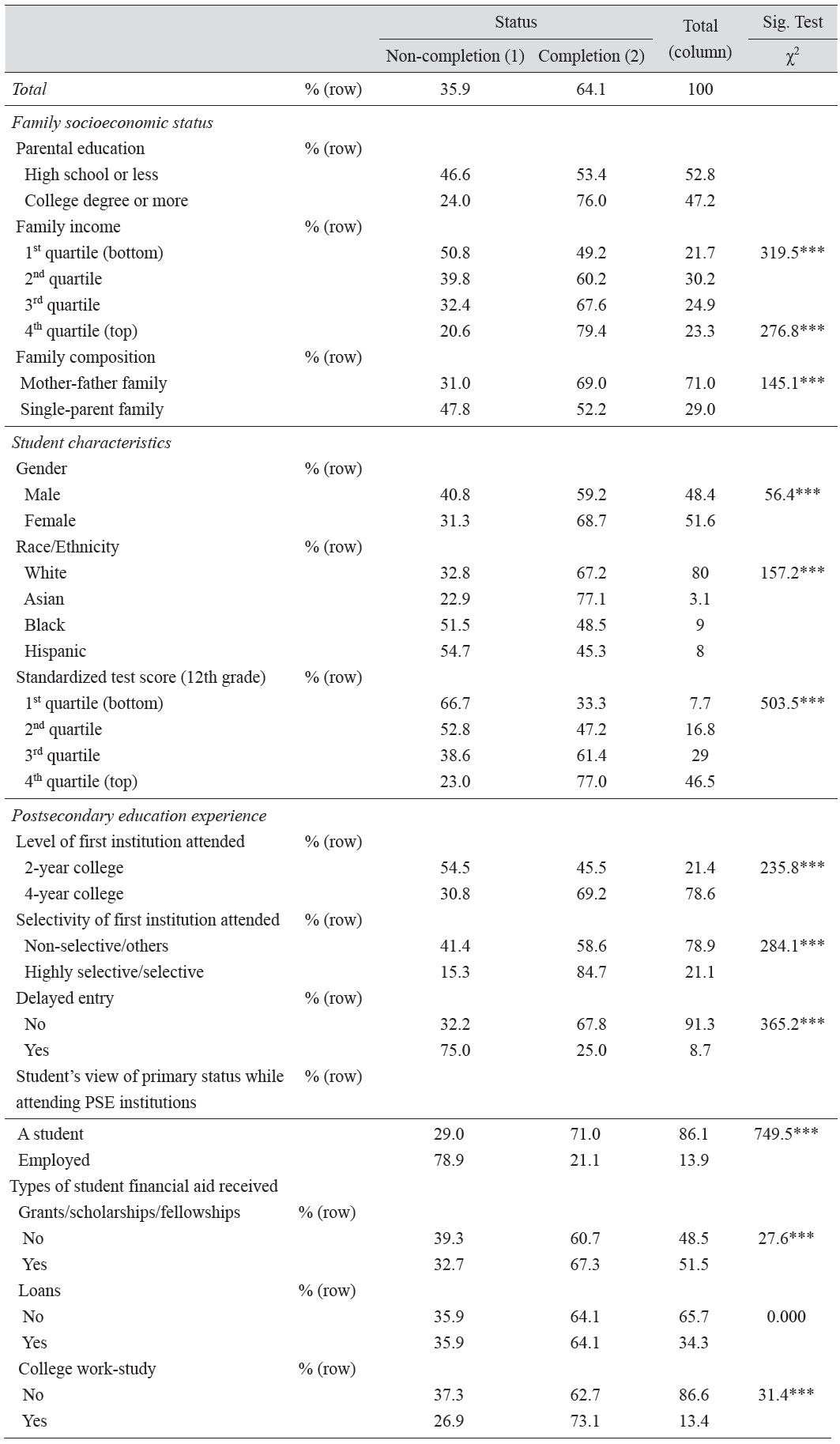

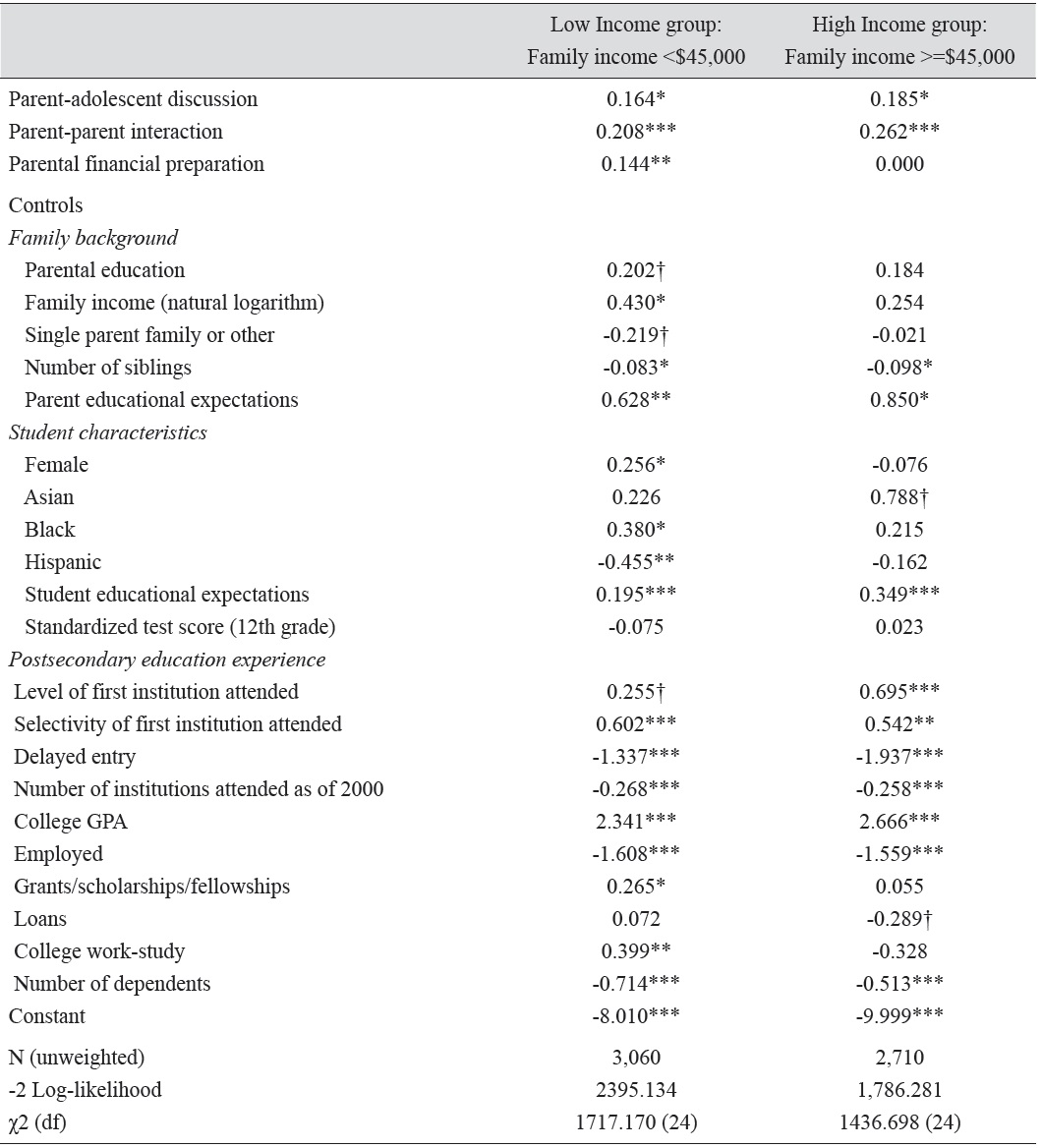

Table 2 shows differences in postsecondary educational attainment status among 1992 NELS high school seniors who had attended a four-year institution by 2000 according to their selected background and postsecondary experience indicators. With respect to family background, 76 percent of students whose parents attended college received a bachelor’s degree within eight years of graduating from high school, while approximately 54 percent of first-generation college students earned a bachelor’s degree within the same timeframe. Approximately 80 percent of students from households in the top 25 percent of the income distribution earned a four-year degree, while only 50 percent of students from households in the bottom 25 percentof the income distribution earned a four-year degree. Approximately 70 percent of students from traditional mother-father families completed a four-year postsecondary education, while only about 52 percent of students from single-parent families earned a four-year degree.

Percentage Distribution for the Four-year College Education Completion Status of 1988 NELS Students by Selected Characteristics

With regard to student characteristics, of those who had attended a four-year postsecondary institution at any time after graduating from high school, approximately 70 percent of female students earned a bachelor’s degree, compared to approximately 60 percent of male students. Sixty-seven percent of white students and 77 percent of Asian students earned a bachelor’s degree, compared to less than half of black and Hispanic students. Approximately 77 percent of students whose standardized test scores were in the top 25 percent of the distribution earned a bachelor’s degree, while approximately 33 percent of students whose scores were in the bottom 25 percent succeeded in earning a four-year degree.

Finally, with respect to the various measures of postsecondary education experience, only about 46 percent of students who began their postsecondary education at a two-year institution earned a bachelor’s degree, compared with approximately 70 percent of students who began their postsecondary education at a four-year institution. Approximately 85 percent of students who began their postsecondary education at a selective or highly selective institution received a bachelor’s degree, while approximately 59 percent of students who began their tertiary studies at a non-selective institution did so. Approximately 68 percent of students who entered college immediately after high school earned a bachelor’s degree, whereas approximately 25 percent of those who delayed their entry to postsecondary education graduated with a four-year degree. Of those who primarily considered themselves to be a student, approximately 71 percent received a four-year degree. In contrast, only 21 percent of those who primarily considered themselves to be employed earned a four-year degree. Approximately 67 percent of students who received grants or scholarships earned a bachelor’s degree, compared to approximately 61 percent of those who did not benefit from a grant or a scholarship. Sixty-four percent of students who received loans earned a bachelor’s degree, the same as the proportion of those who did not receive a loan. Approximately 73 percent of students who held a college workstudy position at least once during their period of study at a postsecondary institution completed their bachelor’s degree, compared to approximately 63 percent of those who did not hold a college work-study position at any time. In summary, while some student, family, and postsecondary education factors appear to operate as facilitators of college completion, other factors appear to function as barriers. In the section that follows, we examine factors associated with parental financial preparation for their adolescent’s postsecondary education using OLS regression models.

>

The Role of Social Capital in Parental Financial Preparation

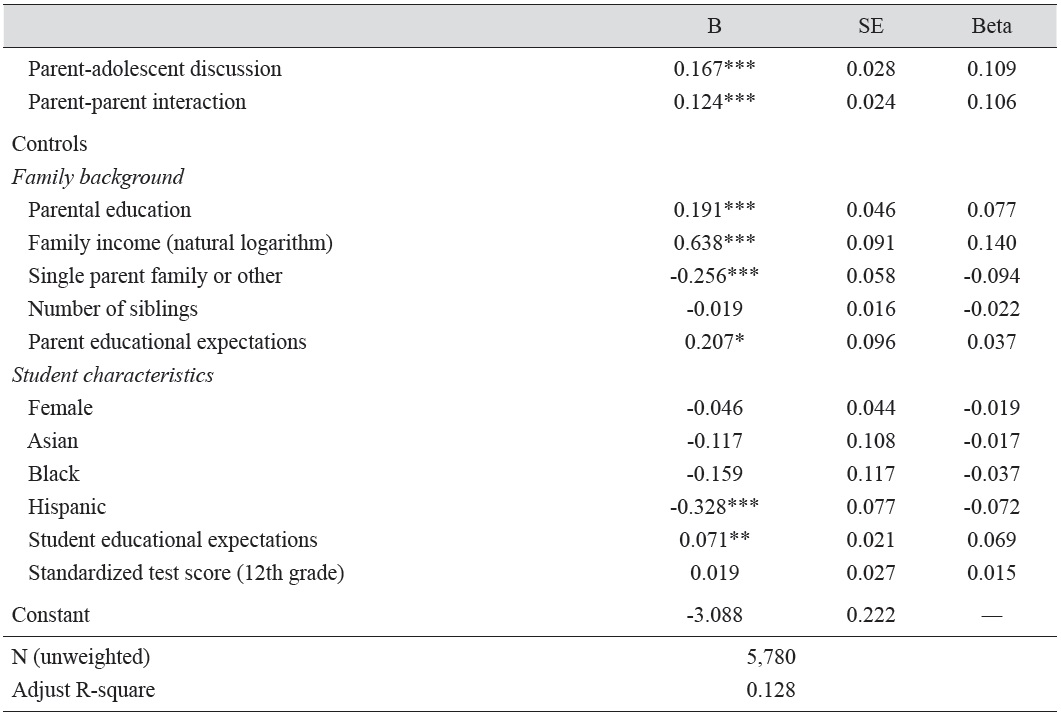

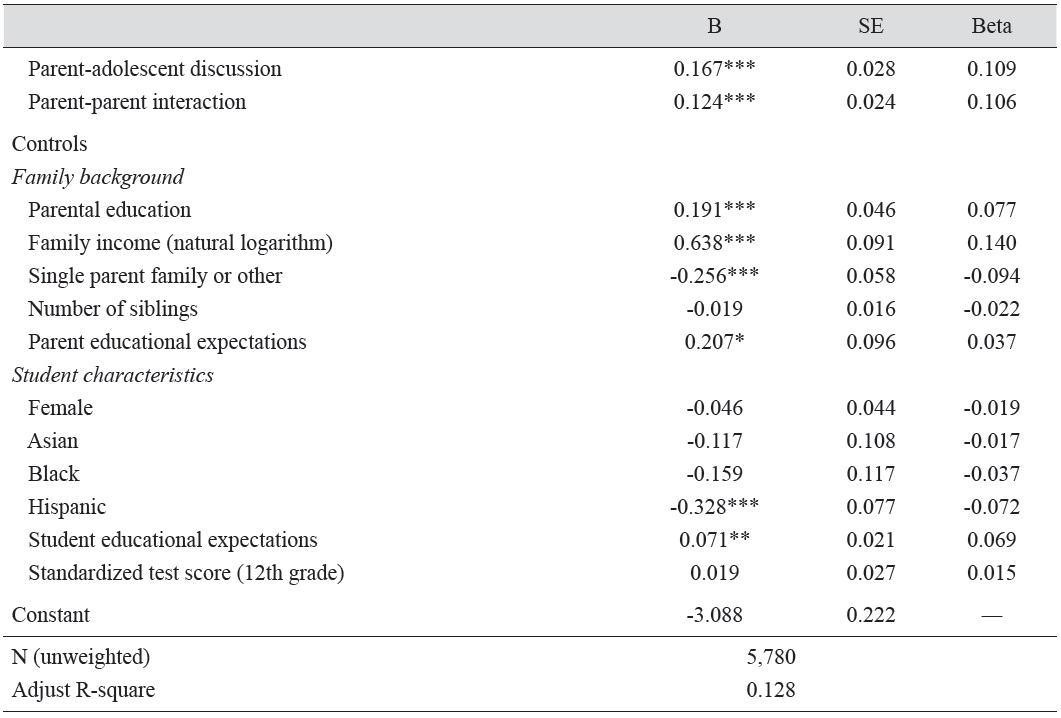

Table 3 shows the determinants of parental financial preparation for adolescents’ postsecondary education. Results revealed the importance of the role played by social ties between parents and their adolescents and between parents and parents of their adolescents’ friends. Both types of social capital were positively related to the degree of parental financial preparation. Furthermore, the relative importance of parent-adolescent discussion (beta = .109) and parentparent interaction (beta = .106) were far greater than those of parents’ human capital (measured by parental education) (beta = .077) and adolescent’s human capital (measured by prior ability) (beta = .015). Yet, financial capital (beta = .140) played the most important role in determining the degree of parental financial preparation.

OLS Regression Predicting Parental Financial Preparation for Teenager’s Postsecondary Education

Results also indicated a significant role of family background in shaping the extent to which parents financially prepared for their adolescent’s postsecondary education. Both parental education and family income were positively associated with the degree of parental financial preparation. Non-traditional families had a negative association with the extent of parental financial preparation. Family size was also negatively associated with parental financial preparation, but its association was statistically non-significant. Parental expectations were positively associated with the degree of parental financial preparation for adolescents’ postsecondary education.

Some, but not all, of the student characteristics also had a significant effect on the extent to which parents financially prepared for their adolescent’s postsecondary education. For instance, there were significant differences between Hispanic and white students in the extent of parental financial preparation for adolescents’ college education favoring white students. Few differences in the degree of parental financial preparation were observed between white and Asian students and between white and black students. Students’ educational expectations were significantly related to the degree of parental financial preparation. Neither gender nor prior ability was significantly associated with the degree of parental financial preparation.

>

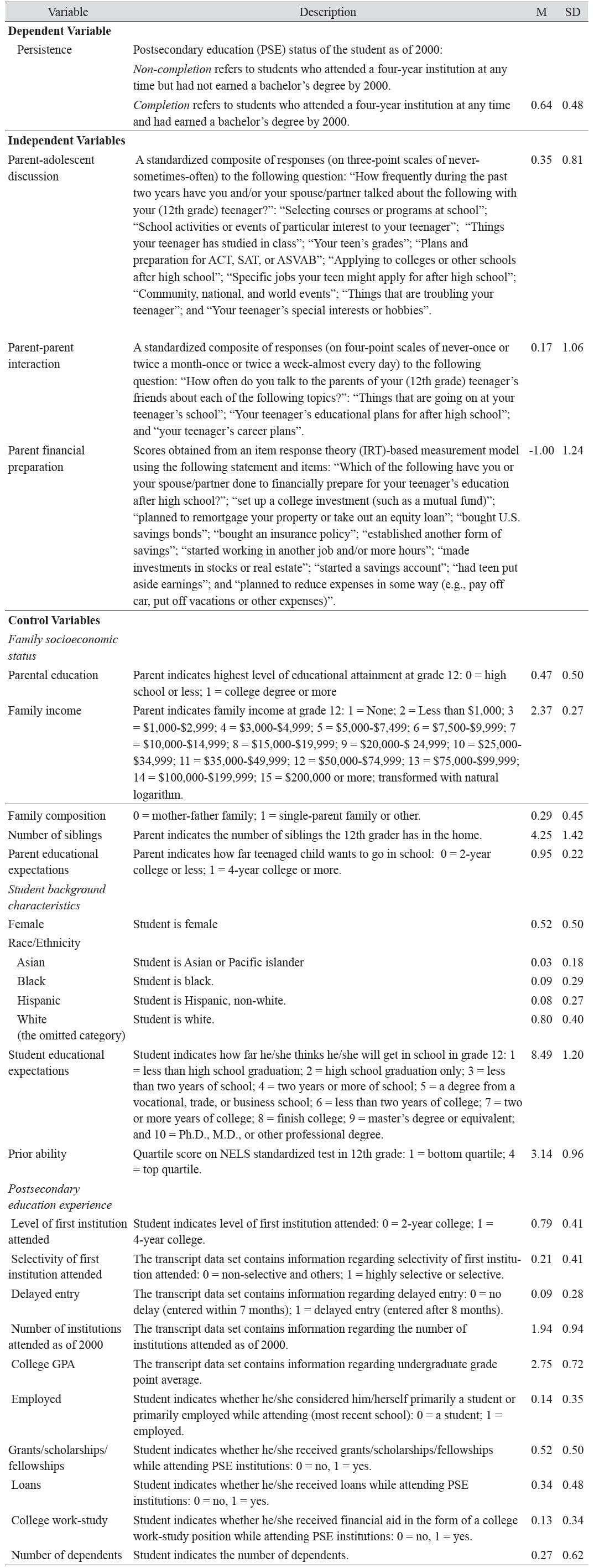

The Roles of Social Capital and Parental Financial Preparation in College Completion

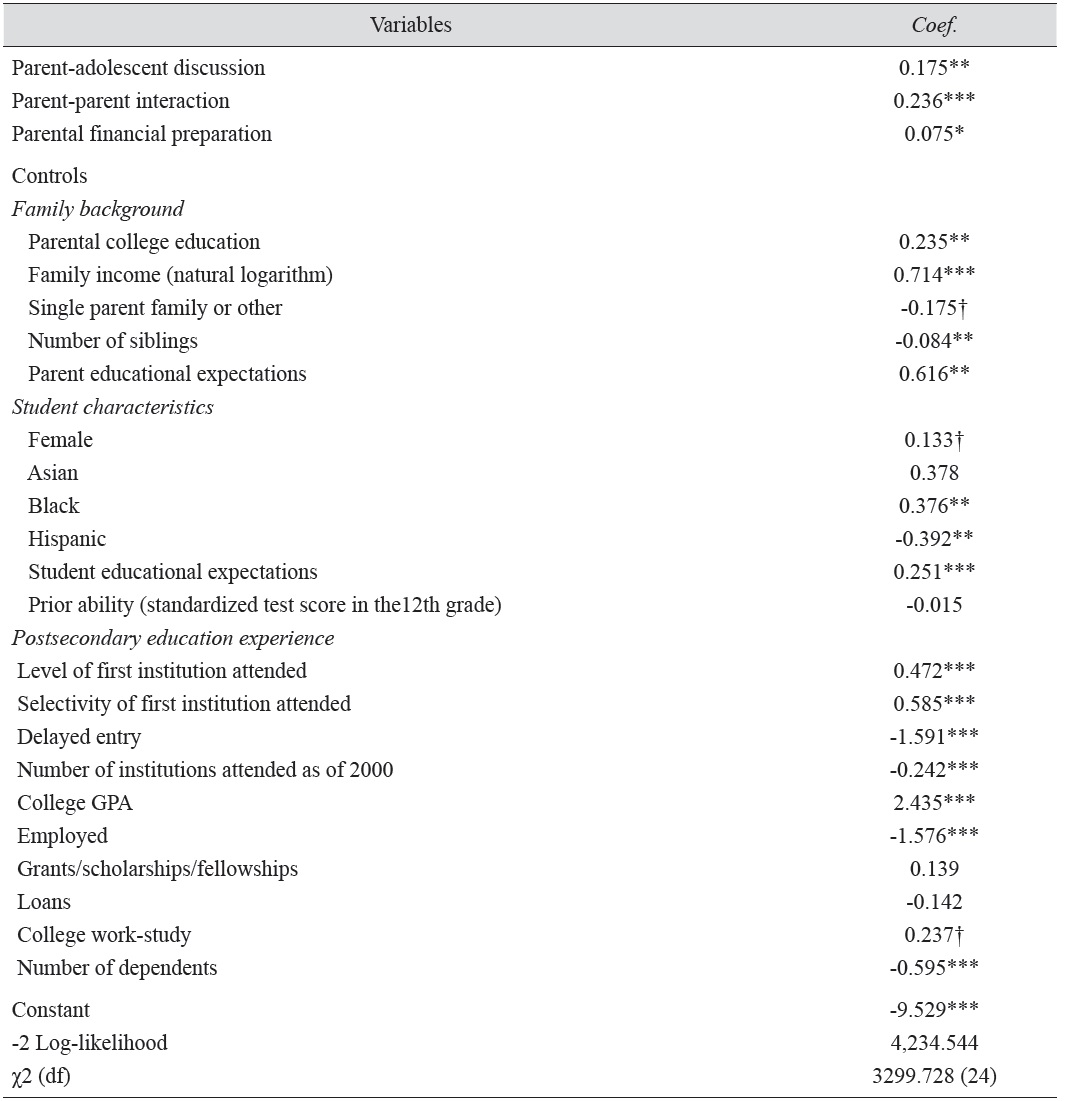

Table 4 shows logistic regression results for the effects of social capital and parental financial preparation on the likelihood of college completion. Results showed that both types of social capital (i.e., parent-adolescent discussion and parent-parent interaction) were positively associated with the likelihood of an adolescent completing a four-year college degree, even when other factors were controlled for. Furthermore, parental financial preparation for adolescents’ postsecondary education significantly increased the likelihood that adolescents would complete their four-year college degree, even after controlling for other variables.

[Table 4.] Logistic Regression Models Predicting the Likelihood of Four-Year College Completion

Logistic Regression Models Predicting the Likelihood of Four-Year College Completion

Before turning to the possible differential effect of parental financial preparation by the level of income, we examine the control variables that were significantly related to the likelihood of an adolescent completing a four-year college degree. All of the family factors were significantly associated with the likelihood of college completion among adolescents, suggesting the importance of family background. Specifically, both parental college education and family income significantly increased the odds of adolescents earning a bachelor’s degree. Single parenthood has a significant and negative effect on the likelihood of four-year college completion. An increase in the number of siblings was associated with a decrease in the likelihood of the adolescent completing a four-year college degree. Parents’ educational expectations were positively associated with the likelihood of an adolescent completing a fouryear college degree, even when other factors were controlled for.

Some of the student characteristics also mattered to four-year college completion. Specifically, female students were more likely than male students to complete a four-year college degree within eight years of graduating from high school when all other variables were controlled for. After controlling for other factors, black students were more likely than white students to complete a four-year college. On the other hand, being a Hispanic student decreased the odds of college completion in comparison with white students. Students’ educational expectations significantly increased their odds of earning a bachelor’s degree. Prior ability measured by the standardized test score attained in the 12th grade had a significant effect on the likelihood of the student earning a bachelor’s degree.

Finally, many of adolescents’ college experiences were significantly related to the likelihood of college completion. First, both the level and the selectivity of the first postsecondary institution mattered to the likelihood of attaining a bachelor’s degree. Not surprisingly, both delayed entry and an increase in the number of institutions attended as of 2000 significantly decreased the odds of completing a four-year college degree. An increase inthe average college GPA was significantly associated with an increase in the odds of college completion. Considering oneself to be employed while in college significantly decreased the likelihood of college completion. Whereas whether students received grants or loans made little difference to the likelihood of college completion, holding a college work-study position made a significant difference to the four-year college completion rate. Finally, an increase in the number of dependents adolescents had to support while attending college (as of 2000) significantly decreased the odds of four-year college completion. In the following section, we examine whether the effects of parental financial preparation on four-year college degree completion vary according to the level of family income.

>

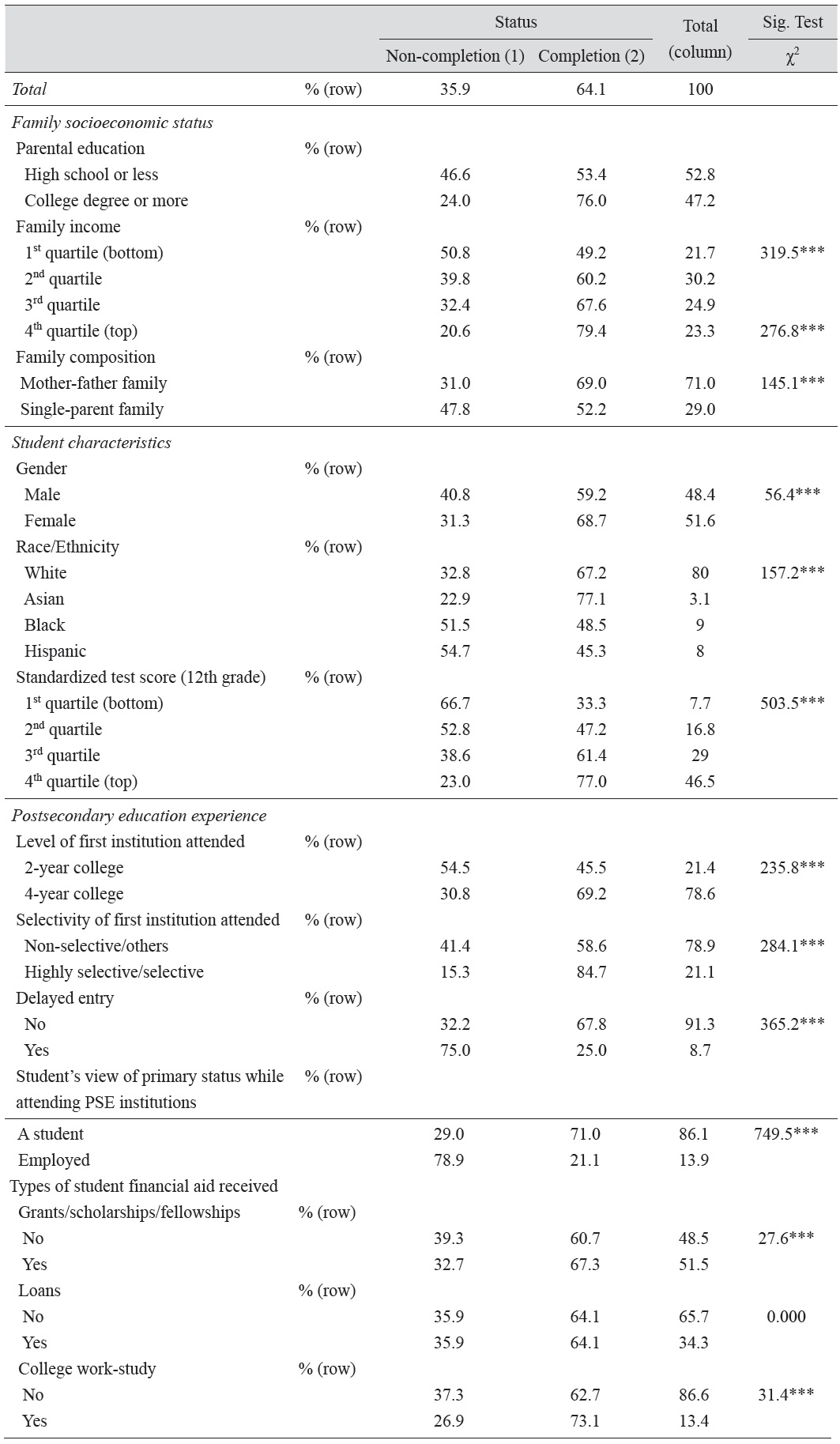

The Varying Role of Parental Financial Preparation by the Level of Family Income

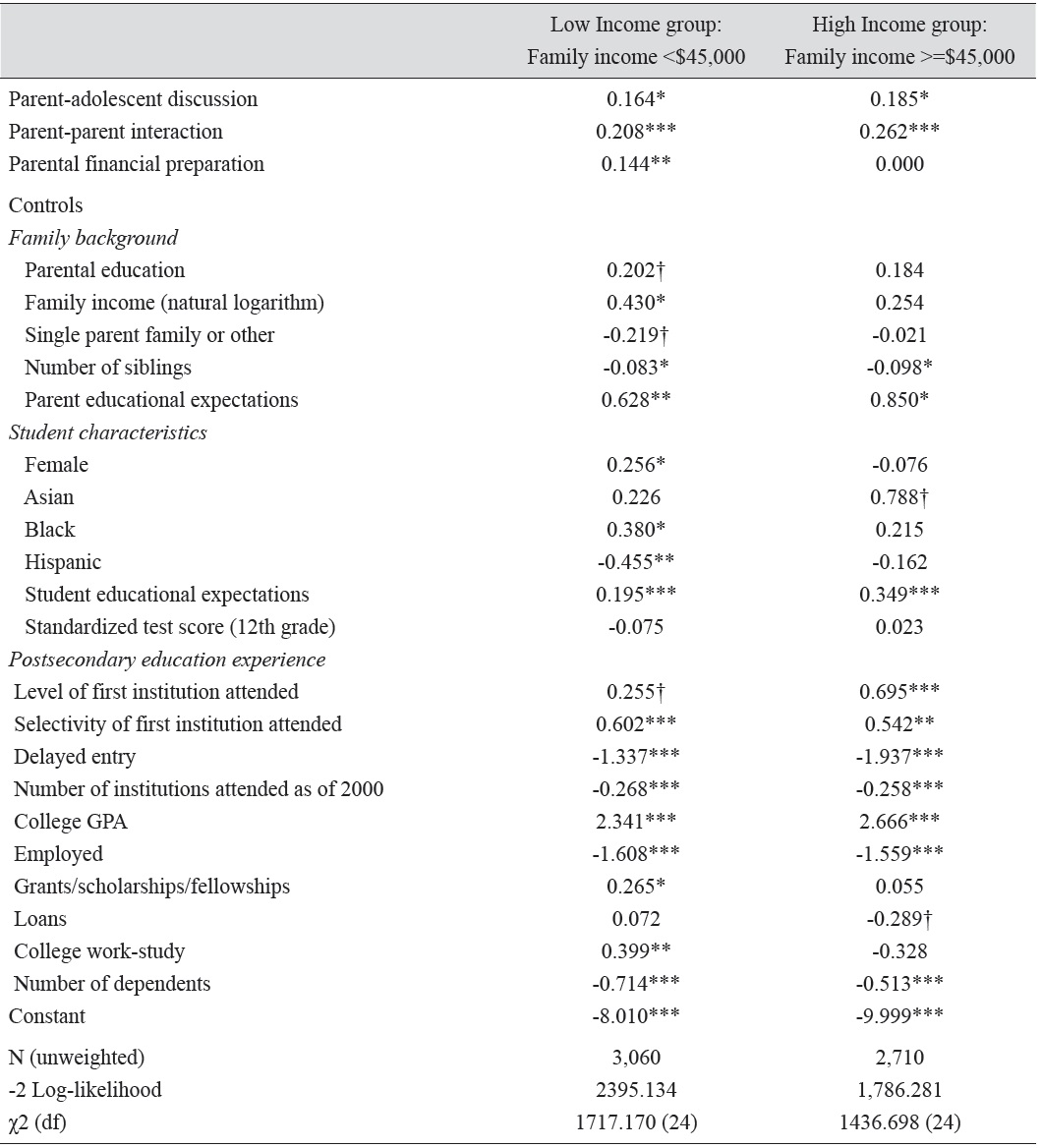

Table 5 shows the logistic regression estimates of the effect of parental financial preparation on four-year college completion among adolescents by the level of family income. Recall that we expect that the degree to which parents financially prepare for their adolescent’s postsecondary education might have a differing effect on the adolescent’s commitment to college education depending on the extent of the parents’ economic resources, with a greater effect being observed for adolescents from low-income families. To test this prediction, we estimated the logistic regression model separately for high- and low-income families.

Logistic Regression Models Predicting the Likelihood of Four-Year College Completion by the Level of Family Income

Results showed that parental financial preparation had a strong and positive effect on college completion among adolescents for the low-income group, whereas it had no significant effect for the high-income group. This result indicated that, as expected, parental financial preparation made to support their adolescent’s postsecondary education had a greater impact on college completion among adolescents from low-income families than it did on college completion among those from high-income families.

It is important to note several contrasting patterns of factors associated with four-year college completion between low- and high-income groups. First, parental education and family income were found to have a significant effect on completion only among adolescents from low-income families. In other words, for the high-income group, neither parental education nor family income was a significant predictor of four-year college completion among adolescents. Single parenthood was also found to have a significantly negative effect on completion only for adolescents from low-income families. Likewise, being a female student was significantly associated with college completion only for adolescents from low-income families. The advantage of blacks and the disadvantage of Hispanics in college completion in comparison with white students were also found for the low-income group only. Financial aid in the form of a grant (or scholarship or fellowship) or a college work-study position significantly increased the odds of college completion among adolescents in the low-income group, but this was not the case for the high-income group. On the other hand, when the type of financial aid given was a loan, this significantly decreased the odds of college completion among adolescents in the high-income group, although it made little difference for those in the lowincome group.

Over the past few decades, social capital has captured the attention of educational researchers and policymakers as an important source of educational attainment in America’s schools (Dika and Singh 2002). Numerous studies in the literature have examined the role of social capital in various educational outcomes including GPA (Israel

Our analyses of the NELS:1988/2000 data confirmed that family socioeconomic background measured by parental education and family income was a significant predictor of college completion among adolescents. However, one important finding was that two forms of social capital–parent-adolescent discussion and parent-parent interaction–had a direct or indirect influence on the success of adolescents in college through their influence on parental financial preparation, even after controlling for other variables. Another key finding was that parental financial preparation had a significant influence on the odds of college completion, especially for adolescents from low-income families. For students from low-income families, specific forms of financial aid such as grants or scholarships and college work-study positions were also found to have a significant effect on college degree completion.

Taken together, our findings suggest that social capital measured both within the family and between families, parental financial preparation, and institutional financial support make a significant difference to disadvantaged adolescents’ completion of four-year college. These findings are in line with existing policy and research focusing on how to deliver financial resources that help low-income students to complete college. However, this study also shows that parents who strategically manage their children’s educational careers go beyond their own structural constraints by activating social capital both within and outside the family and obtaining the information needed to ensure their children manage to complete a four-year college degree. This tells us that financial aid programs which are not complemented by social resources may not be as effective as they would otherwise be, even though the amount of money available from such programs may raise the expectations of students who are academically talented but come from poor families.

Deploring the recent slowdown in the growth of educational attainment in the United States, Goldin and Katz (2008: 7) point out that this trend “has been most extreme and disturbing for those at the bottom of the income distribution, particularly for racial and ethnic minorities.” They blame the lack of academic college readiness among American youth and the lack of financial access to higher education for this slowdown and identify the rise in the share of American children living in poor families and single-parent households since 1970 as a potential hindrance holding back educational attainment in the U.S (Goldin and Katz 2008). While concluding that rising college costs and the complexity of the U.S. college financial aid system double the adversity that youth from low-income families face when they pursue college education, Goldin and Katz (2008) call for social and emotional support to be given to poor children and for financial assistance to be provided for college education to ensure lowincome youth are ready for college.

College knowledge such as accurate knowledge about college costs has recently been added to more traditional measures as one of the important aspects of college readiness (Roderick

The present study has several limitations that need to be addressed in future studies. First, this study was limited to students who attended a four-year college. Accordingly, we did not address the role of social capital and parental financial preparation in two-year college completion among adolescents. Second, the restriction of our analysis to students attending a four-year college may have led to the role played by family background, including parental financial preparation, being underestimated. Disadvantaged students are less likely to enroll in college, especially a four-year college, and thus students enrolled in a four-year college might be relatively homogeneous in terms of family background. On the other hand, this study might overestimate the role of parental financial preparation due to the omission of other important variables (e.g., parental occupation) and to the selection bias inherent in observational data. In other words, the observed net effect of parental financial preparation may be likely to reflect pre-existing differences in family background between adolescents who have financial resources and those who do not. More rigorous methods that address selection bias are needed to test the robustness of the results and assess them for the presence of unobserved covariates or hidden bias. Finally, some of the students whose college completion status was identified as incomplete in this study may eventually earn a college degree, although it may take them a number of years to do so. These students are then likely to be counted as completers. Thus, our estimates of four-year college completion rates and the effects of social capital and parental financial preparation may be subject to change, depending on the timespan of any longitudinal study carried out in future. A longitudinal study with a longer timespan will increase our understanding of the complex patterns of college persistence and completion.

Despite these limitations and the focus on the United States, this study has broader implications for some other countries, including South Korea, where rising tuition bills and mounting student loan debt increasingly become a social issue especially for students from low-income families. In South Korea where 80 percent of high school graduates go to college, tuition has dramatically increased in recent years. From 2002 and 2012, for example, the average tuition increased by 66 percent (from 2.5 million won to 4.1 million won) for public college and by 45 percent (from 5.1 million won to 7.4 million won) for private college(Korean Educational Development Institute 2012). During the same period, the cumulative inflation rate was approximately 39 percent (Korean Statistical Information Service, http://kosis.kr/). As a result, an increasing number of Korean students, especially those from lowincome families, has relied on student loan to pay high tuition, while many are involved in part-time work to repay their debt during and after their college education. Like in the United States, a growing concern in this country is that students from low-income families may likely fall into a debt trap and may be less likely to complete their college education. In this regard, our findings, which highlight the importance of social capital and parental financial preparation in college completion, offer important insights into family strategies conducive to achieve children’s postsecondary goals above and beyond the United States.

Of course, it remains to be seen to what extent our findings based on the United States can be generalizable to South Korea (and other countries). However, we believe that our conceptualization of social capital as a beneficial factor for college persistence via parent financial preparation may be quite relevant for understanding a strong commitment to education among Korean college students. This is because in South Korea it is taken for granted that parents (and other family members) should take a financial responsibility not only for their children’s education but also for some of the costs for assuming adults roles (e.g., marriage), and as a result, the reciprocal relationship between parents and students may be arguably much stronger in South Korea than in the United States (Byun