More than 40 years had passed since the collapse of the Bretton Woods system. Since then, the post-Bretton Woods system had faced various challenges. The imbalanced trade among the United States, Japan, and Germany led to the Plaza agreement. Many emerging countries suffered from economic crises after liberalizing their capital accounts. To prevent another economic crisis, these countries piled up huge amounts of foreign exchange reserves, and this action caused a big international controversy. The recent global financial crisis, which occurred with the global imbalances, generated debates on international monetary system reform.

The international monetary system limits a set of available international monetary policy options for each country. The exchange rate was fixed under the Bretton Woods system, which prompted the need to limit the international capital mobility to obtain monetary autonomy in view of the trilemma. The available policy options for each country change along with the economic environment. If the capital account is liberalized under a fixed exchange rate system, each country has to give up its monetary autonomy in view of the Trilemma.

The post-Bretton Woods system imposed new restrictions on each country’s available policy options. Emerging countries experienced substantial changes in their economy and in their available policy options after the collapse of the Bretton Woods system. Moreover, as emerging countries grew fast, their economic actions started to affect other countries and the entire system.

This study discusses how available international monetary policy options for emerging countries changed over time during the post-Bretton Woods era in view of the trilemma. The available policy options for emerging countries changed along with their economic environment, and this occurrence increased the need for the reform of the international monetary system. After summarizing the current progress in the international monetary system reform, this study suggests that the evolution of the international monetary system will have an important implication on the available policy options of emerging countries.

Section II explains the trilemma and the post-Bretton Woods system. Section III discusses how the changes in the economic environments affected the available policy options for emerging countries. Section IV summarizes the current progress in the international monetary system reform. Section V concludes the study.

II. Post-Bretton Woods System: Early Years

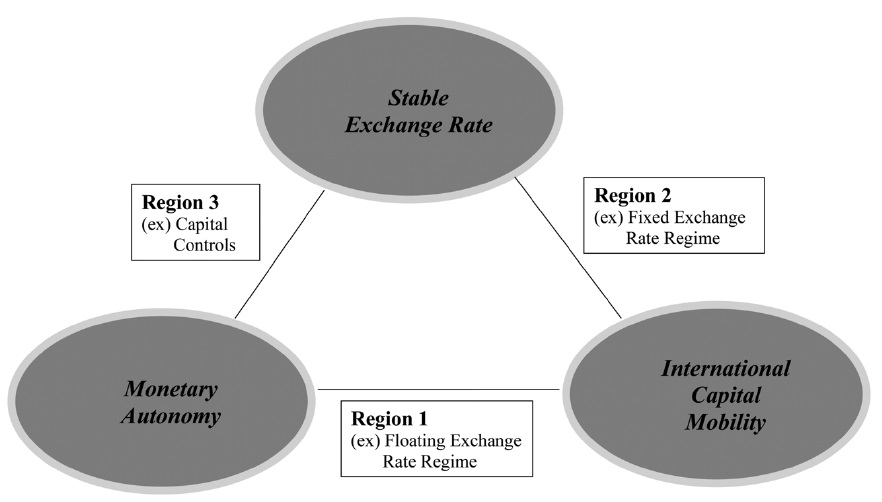

The trilemma describes the international monetary policy frameworks for each country. It involves three policy objectives, namely, stable exchange rate, monetary autonomy, and free international capital mobility, and they are considered beneficial to the economy. A stable exchange rate may promote international trade. Monetary autonomy enables each country to use its monetary policies to stimulate its economy during recession. Free international capital mobility can also benefit the economy, as explained in Section III.A.

Each country can choose two out of these three objectives, a situation from which the term trilemma originated. By adopting the floating exchange rate regime with free international capital mobility (Region 1 in Figure 1), a country can achieve monetary autonomy and free international capital mobility in exchange for its stable exchange rate. By adopting the fixed exchange rate regime with free international capital mobility, a country can achieve a stable exchange rate and free international capital mobility (Region 2 in Figure 1) in exchange for its monetary autonomy, as the monetary policy is used to fix the exchange rate. By adopting capital controls, a country can achieve monetary autonomy and a stable exchange rate in exchange for its free international capital mobility (Region 3 in Figure 1). This theoretical framework is well accepted because it clearly indicates that each country must give up one of its objectives in each region.1

>

B. Post-Bretton Woods System

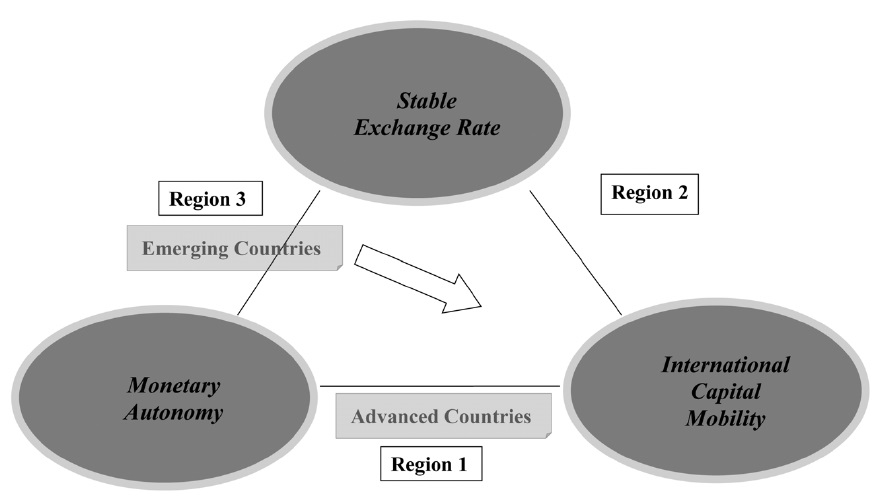

The Bretton Woods system collapsed in the early 1970s, and its collapse launched a new international monetary system. In the post-Bretton Woods system, international coordination and external equilibrium is important, whereas in the Bretton Woods system, internal equilibrium of each country is important. This new system was called a non-system or a hybrid system, in which many advanced countries adopted a more flexible exchange rate regime, whereas most developing/emerging countries adopted a highly managed exchange rate regime. Moreover, advanced countries had a higher degree of international capital mobility than the developing/emerging countries. Many advanced countries had a high degree of international capital mobility during the 1980s, but developing countries continued to impose severe capital controls. In view of the trilemma, developing countries are located in region 3, and advanced countries are located in region 1.

1Aizenman, Chinn, and Ito (2008) found that a rise in the measure of one policy objective is traded off with a drop in the measures of the other policy objectives, thus supported the notion of the trilemma.

III. Changes in Economic Environments

>

A. Capital Account Liberalization of Emerging Countries

Advanced countries experienced an unprecedented economic success after liberalizing their capital accounts. Therefore, they pressured the emerging countries into doing the same, and some countries reluctantly obliged. As shown in Figure 2, this situation implies that emerging countries have moved from region 3 to regions 1 and 2 in the trilemma.

However, instead of becoming successful, these emerging countries encountered certain problems after liberalizing their capital accounts, mostly due to the volatile international capital flows. Their exchange rates and financial markets became unstable, and they often ended in a sudden stop and an economic crisis. Therefore, although the trilemma considers free international capital mobility as a good policy objective, its implication in emerging and developing countries should be reviewed.

Theoretically, international capital mobility can provide various benefits. Countries can smooth their consumption by international lending and borrowing. They efficiently allocate their savings and financial investments through international capital markets. They diversify countryspecific consumption risks and conduct international risk sharing. Diversifying risks through international capital markets could provide opportunities for high return of investments, which may ultimately lead to faster economic growth (Obstfeld 1994).

However, in reality, many puzzles, such as the Feldstein-Horioka Puzzle (Feldstein and Horioka 1980), the Home-Bias Puzzle (or International Portfolio Diversification Puzzle, French and Poterba 1991), the Consumption ― Output Correlation Puzzle (Backus, Kehoe, and Kydland 1992), and the Backus-Smith puzzle (Backus and Smith 1993) have been found. These puzzles tend to imply that international capital flows and markets do not work as predicted by theory, and they suggest that we may not achieve many benefits from international capital mobility.

We also found various costs of international capital mobility in emerging markets. Highly volatile international capital flows often generate excess volatility in emerging financial markets. They also generate boom ― bust cycles, sudden stops, and economic crisis in some cases.2 Emerging countries could only benefit minimally from international capital mobility, but its costs were usually large. Kim, Kim, and Wang (2006), Kim, Lee, and Shin (2008), and Kim and Lee (2012) found a very small degree of consumption risk sharing among emerging Asian countries. Conversely, Kim, Kim, and Wang (2007) reported that the saving ― investment correlation was very high in emerging Asian countries. This high correlation implies that their savings were not efficiently allocated.

All of these findings showed that free international capital mobility was not a viable option for emerging countries. Given its huge costs, the flexible or fixed exchange rate regime with international capital mobility (regions 1 and 2) was no longer an option. The only remaining choice was to move back to capital controls (region 3). However, trends of liberalization and peer pressure were observed in the international society before the global financial crisis. Thus, emerging countries encountered difficulties in re-imposing capital controls and thus in choosing any of these policy combinations.

After experiencing a devastating economic crisis, emerging countries began accumulating huge reserves to avoid another crisis.3 This action is viewed as an effort to open up regions 1 and 2 as viable options. Many studies have affirmed that the high level of foreign exchange reserves decreases the chances of crisis.4

However, such reserve accumulation is costly for reserve holders because these reserves are safe assets that offer very low interest rates.5 The accumulation also involves distortions and inefficiencies, as the government only accumulates safe foreign assets that distort the portfolio decision of the private sector and of the whole country. Reserve ac-cumulation also involves systemic costs and may influence interest rates in reserve centers. It may also become excessive because of competitive reserve hoarding.

Moreover, the current system may not be sustainable. The demand for reserves in emerging countries will likely increase further, but creditworthy advanced countries will not be able to meet such demands. The demand will continuously increase as emerging countries grow faster than advanced countries. This demand will increase even faster as the financial globalization progresses further. Credit-worthy advanced countries will have to issue more gross government debts to meet such demands. However, this action implies that the governments of advanced countries run on continuing deficits and that they need to back up their debts by acquiring risky assets. Therefore, government debts of advanced countries will likely become risky and will not properly function as reserves.

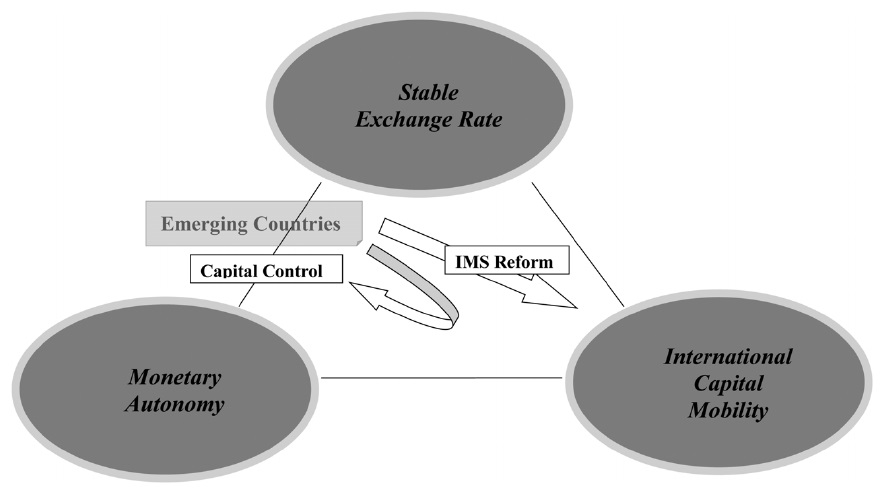

As the current pace of reserve hoarding will be difficult to maintain in the long term, the following two possibilities remain. First, the global economy may establish a proper global liquidity provision system that can stand amid highly volatile capital flows or the financial globalization. This system will enable emerging countries to reside safely in regions 1 and 2 without the need for hoarding foreign exchange reserves. Second, emerging countries may go back to capital controls by directly regulating international capital flows. In other words, emerging countries may make regions 1 and 2 viable by replacing reserve hoarding with a proper global liquidity provision through the reform of the international monetary system, or emerging countries may move back to region 3 by re-imposing capital controls (Figure 3).

2For example, Kim, Kim, and Wang (2004) and Kim and Yang (2011a) documented that capital flows generate boom ― bust cycles and asset price fluctuations in emerging Asian countries. 3Some studies, such as Aizenman and Lee (2007), empirically supported the precautionary motive of reserve hoarding, whereas others, such as Obstfeld et al. (2010), Hashimoto (2008), and Dominguez (2010), concluded that the reserve accumulations are not excessive. 4See Kaminsky, Lizondo, and Reinhart (1998) for surveys on early studies, and Frankel and Saravelos (2010) for the study on the episode of the recent global financial crisis. 5See Obstfeld (2011) for a more detailed discussion on the costs of reserve hoarding and the sustainability of the current system.

IV. Progresses in the Reform of the International Monetary System

This section briefly reviews the current progress in the reform of the international monetary system. The international community actively discussed such reform after the global financial crisis. The reform undergoes slow progress especially in the G20. Some aspects of the global liquidity provision system’s structure are still not agreed upon, such as whether to use a single or multiple currency system, or whether the SDR could be used as the main reserve currency. Therefore, many people expect that accomplishing the fundamental reform will take considerable time. Apart from the fundamental reform of the international monetary system, progress and discussion have been conducted as regards the building of global financial safety nets and capital controls.

>

A. Global Financial Safety Nets

Global financial safety nets are international cooperative systems that provide global liquidity to avoid a crisis. Global financial safety nets have various layers, such as bilateral, regional, and global arrangements. The bilateral currency swap is a bilateral arrangement, the Chiang-Mai Initiative Multilateral (CMIM) is a regional arrangement, and the various liquidity provision methods of the IMF are global arrangements. Global financial safety nets need to satisfy certain conditions to function properly. First, they should provide funds sufficiently to prevent a crisis. Second, they should ascertain their provision of funds whenever needed. Third, no stigma effect should be present. Fourth, they should minimize the moral hazards. The IMF developed various facilities in the G20, such as the Flexible Credit Line, the Precautionary Credit Line, and the Precautionary and Liquidity Line.6

Global financial safety nets have faced many problems. Although many IMF facilities have become flexible in recent years, they seem to suffer from certain stigmas. Asian countries have recently avoided these facilities because of their bad experiences with these facilities during the Asian financial crisis.7 The CMIM has insufficient funds to rescue large member countries from crises. Moreover, its surveillance mechanism should be developed further.8 The currency swaps incur limitations because they are primarily temporary. Future endeavors should connect these layers of arrangements much closer.

Nevertheless, the development of global financial safety nets is not a true fundamental reform of the international monetary system. Global financial safety nets are used to supplement the current international monetary system or global liquidity provision system. Given that the international monetary system reform will take a long time, the development of global financial safety nets is valuable. However, the global economy will eventually need to reform the international monetary system.

Issues on capital controls were also discussed in the G20 after the global financial crisis. The views on capital controls varied among advanced and emerging countries. Emerging countries suggested that the imposition of capital controls was a sovereign right of each country. However, advanced countries argued that capital controls would result in externalities, which provided them with a reason to disallow such imposition. Some countries were blamed for using capital controls to devalue their currency and improve their exports, as they would negatively affect other countries.9,10

These conflicting views were settled in the Coherent Conclusion at the 2011 Cannes G20 summit, which proposed that capital controls could be used but should be reversed upon the abatement of destabilizing pressures.11 Despite this compromise, no detailed agreements have been met on certain issues, such as which types of capital controls are allowable, under what exact conditions capital controls are allowable, and how long they are allowable. Therefore, future disputes will be very likely. Furthermore, such consensus was only made in the G20, and it might not be accepted by other international communities such as the OECD.

To summarize, regions 1 and 2 can be considered viable choices for emerging countries, with proper global liquidity provision by the reform of international monetary system. However, such reform will take a very long time to achieve. Global financial safety nets may help, although not fundamentally, in the interim. Aside from global safety nets, the only alternative for emerging countries is to re-impose capital controls (moving back to region 3). The issues on capital controls are not clearly agreed upon in the global economy, but if regions 1 and 2 cannot be considered viable choices for emerging countries, they will have no choice but to re-impose capital controls.

6Refer to Kim and Yang (2012) for details. 7Refer to Ito (2012). 8Refer to Kim and Yang (2011b) for the current problems of the CMIM. 9Refer to Bautista and Rhee (2011). 10In the G20, the capital controls are differently defined from prudential policy in the following manner: when discrimination based on residency exists, then it is considered as a capital control. 11Refer to G20 (2011).

The future evolution of the international monetary system is crucial for emerging countries. It will dictate the options on international policy frameworks for emerging countries in the future. The careful handling of highly volatile international capital flows and the proper provision of global liquidity will directly affect the available policy combinations for emerging countries. The fundamental reform of the international monetary system and the global liquidity provision system will assist emerging countries in coping with their liberalized capital accounts. However, the realization of such reform will require a considerable period. Properly developed financial safety nets and/or sustainable accumulation of reserves may help emerging countries in the interim. If they cannot rely on these two solutions, emerging countries will have no choice but to re-impose capital controls.

To make more options available, emerging countries have to draw international attention to the reform of the international monetary system. However, they cannot achieve such reform all by themselves, as the international monetary system also governs advanced countries. Advanced countries need to understand the options of emerging countries. Advanced countries have blamed emerging countries for hoarding reserves and imposing capital controls, which may have led to competitive devaluation and global imbalances. However, given the current situation of emerging countries, advanced countries must not criticize their choices on international monetary policy frameworks. Emerging countries will not have any viable options under the current international monetary system with free international capital mobility if the hoarding of reserves and the imposition of capital controls are disallowed. Their situation becomes worse if their accumulation of reserves is not sustainable in the near future. This tension between emerging and advanced countries may eventually lead to trade war, competitive devaluation, financial war, and currency war. In this regard, advanced countries must strive together with emerging countries for an international monetary system reform that can reflect the recent worldwide developments. Given that the realization of such a reform may require a considerable period, advanced countries should also focus on the development of global financial safety nets.