ㅁ modern South Korea might balk at the idea of having its political leader engaging in an ‘immoral’ act of homosexuality, but this was not always the case throughout Korean history. Several kings, such as Hyegong of the ancient Silla and Kongmin in the Koryŏ period, were known for their homosexual behavior. The Neo-Confucian Chosŏn may not have been as lenient as the previous kingdoms, yet there is plenty of evidence for the continued existence of homosexuality in publicly or semi-publicly acknowledged forms. Even the introduction of sexology and the establishment of modern heterosexual norms under Japanese rule failed to wipe out their persistence at least until the 1940s (Chŏn 1980; Pak 2006; Ch’a 2009). Thus it is no surprise to see Korean queer cinema often borrowing its motifs from the pre-modern times, as the wildly popular film The King and the Clown (Wang ŭi namja, 2005) did with a midong (beautiful boy) character that typically played female roles in a namsadang all-male entertainment troupe.

The beginning of Korean queer or LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) communities in the modern sense is said to date back to the mid-1970s when the Nagwŏndong area, in the venerable Chongno district of Seoul, emerged as a “Gay Paradise” with a number of bars, bathhouses, and movie theaters attracting predominantly male homosexual clientele. Perhaps there is no better symbol for the deep connection between homosexuality and cinema than the legendary Pagoda Theater at the heart of Nagwŏndong, where Korean gays had secret encounters with one another or their international partners (Ch’oe 1996; Seo 2001; Cho 2003).

About two decades later, the LGBT movement sprang out in the aftermath of the democratic breakthrough in South Korea. A few glimpses of the early Korean LGBT movement were captured by The Grace Lee Project (2005), in which a Korean-American activist paid a dear personal price for her involvement in the very first Korean homosexual organization Ch’odonghoe and then the first lesbian advocacy group Kkirikkiri (Pak 2000, Shimizu 2007). Ever since the beginning, the Korean LGBT movement has been closely tied to the film culture/ industry in one way or another as we shall see later on.

A decade has barely passed since Jooran Lee wrote, “Discussing Korean gay and lesbian films is like drifting in a space without sunlight or oxygen” (2000, 273). We may be still drifting, but now there is much to bask and breathe in thanks to many filmmakers who ventured to fill the dicey space of homosexuality and queerness with their work. What we do here is to take a first stab at periodizing the history of Korean queer cinema in the hopes for more detailed, interpretive research to follow. In terms of visibility of queerness, we divide the history into three periods: the Invisible Age, the Camouflage Age, and the Blockbuster Age. Describing each of the periods, we will try to contextualize some of the representative films in the broader sociocultural milieu.

The name ‘Invisible Age’ is garnered from the idea that for many years, those filmmakers who wanted to bring homosexual themes to the forefront of their movies were unable to do so because of societal pressures against it, and instead laid the themes down discretely, invisible to the heterosexual eye; such themes would only be recognizable by members of the audience already familiar with homosexual content and indexicalities. In this sense the Invisible Age might well have begun at the birth of Korean cinema, but there is one problem. As early as in 1931, a film project entitled Women of Tomorrow (Myŏngil ŭi yŏin) was announced in a daily newspaper, inspired by the much scandalized real-life story of lesbian double suicide (Ch’a 2009, 69). Apparently this project never materialized, but it does suggest more visibility, and less inhibition, in dealing with the issue of homosexuality among filmmakers and the public in the colonial times rather than after.

If the modern heterosexual norm and homophobia settled in during and after the Pacific War mobilization and the Korean War periods as some of the aforementioned studies indicate, then it might be prudent for our purpose to set the starting point of the Invisible Age in 1945, when Korean ‘national’ cinema formally launched its post-colonial journey. This period runs until 1997, a turning point that will be discussed further on. There were films released in this era that exhibited explicitly homosexual themes, however, they remain elusive and hard to learn too much about beyond discussions of them in a few academic articles.

The actor and filmmaker Ha Myŏng-jung once claimed that The Pollen of Flowers (Hwabun, 1972), which his legendary brother Ha Kil-jong had directed and in which he himself had played the role of homme fatale, was “the first gay film in Korea” (Ha 2008).1 While homosexuality and the tension it creates among the characters were clearly on display, as a hypersexual avant garde film Pollen had so many other “shocking” and “perplexing” aspects at the time of release that even those critics and scholars who rediscovered the importance of the film decades later did not seem to regard it primarily as a queer film (Pak 2009; Yi 2009). Nevertheless, Pollen is the earlier and better known one of the two films queer activists of the 1990s–2000s dusted off of the shelves of the national film archive. The other has the more explicit title though—Ascetic: Woman and Woman (Kŭmyok: Yŏja wa yŏja, 1976).

Ascetic is the tale of two women, a young aspiring fashion model named Yŏnghŭi and her middle-aged patron Mi-ae, who is an artist. They begin cohabitation after Yŏng-hŭi had a mental breakdown during her model debut. Mi-ae’s intimate care helps her younger lover get back on her feet personally as well as professionally. But now-recovered Yŏng-hŭi falls in love with a man, leaving her partner in the cold. Having suffered from a physically abusive husband in a previous marriage, Mi-ae begs Yŏng-hŭi not to take the heterosexual path. Nevertheless, Yŏng-hŭi goes with the man who eventually betrays her, and then comes back only to discover Mi-ae’s suicide.

Kim Su-hyŏng, a specialist in the so-called ero yŏnghwa (erotic film)—ero in short—genre that would later come to dominate the Korean film industry from the late 1970s through the 1980s, made Ascetic as racy as possible given the circumstance of heavy censorship. Mi-ae is seen body-painting all over Yŏng-hŭi’s naked body in one scene, and releasing cockroaches on her bare back in another. All these thinly-veiled sex acts are described as “therapy” for Yŏng-hŭi, who had been sexually assaulted and traumatized by three unknown men. In terms of eerie atmosphere and shocking display of sexuality, this film provides a bridge between such experimental cult films as Kim Ki-yŏng’s Housemaid trilogy and the commercialized soft pornography of ero in the 1980s.2

Despite winning an award the year it was released, Ascetic remained a fairly unknown film. It was lost in between the worlds of lesbianism and feminism, with critics from both sides arguing that it does not go far enough to be truly a film for either cause. Korea’s first officially registered LGBT magazine Buddy came to the defense of Ascetic, calling it Korea’s first lesbian film. However, its invisibility in the larger film community is characteristic of works from the invisible age; it might have brought a taboo topic such as lesbianism to the fore, yet the film itself was too ‘invisible’ in the eyes of the public to create much of an impact. The risquéness of female homosexuality could have been well exploited by the typical male voyeurism of the ero genre, but it did not happen until Sabangji (1988) came out with a different twist. Sabangji is the name a hermaphroditic character—based on a Chosŏn-era sex scandal—who played a male partner role for sexually oppressed upper-caste women. Lesbianism and transsexuality in the ero films therefore offered little aid for making the LGBT theme visible on its own terms.

The chain of invisibility and silence about homosexuality was finally breached within the Korean film community when Pak Chae-ho released Broken Branches (Naeillo hŭrŭnŭn kang, 1995), driving the controversial topic straight into the heart of the Korean Confucian social system, the patriarchal extended family. Conceived as a socially-conscious drama, Broken Branches tells the story of a gay man named Chŏng-min growing up in a traditional Confucian household during the 1960s–70s; the son of his father’s third wife, he saw his older siblings rebel strongly against the patriarchal family structure they were raised in, yet continued to live under such rule until the father’s sudden death at the end of the 1970s. Now a young adult ‘liberated’ from patriarchal control, Chŏng-min begins dating a middle-aged man named Sŏng-gŏl, who recommends Chŏng-min to get married to a woman just as he himself did for camouflage. In the end, Chŏng-min goes to the seventieth birthday party for his stepmother—his father’s second wife who now represents the declining Confucian authority—and makes her faint by introducing Sŏng-gŏl as his ‘wife.’

Whether it is an act of defiance, or a gesture of reconciliation in which Chŏng-min “both fulfils his family obligations and simultaneously produces a space for his gay identity within the family” (Berry 2001, 218) is a matter of interpretation. But for all its respectable effort to make the topic less controversial and more accessible to the general public, the film’s insinuation of Chŏng-min’s homosexuality being a consequence of patriarchal oppression and broken family life did not sit well with the contemporary gay activists (Im 2000, 81–82). Considering that the Korean LGBT movement was just taking off around the same time, it was rather unfortunate that Broken Branches did not resonate at all with some of the most visible, outspoken members of the emerging LGBT community. The film’s up front manner in dealing with homosexuality definitely signaled a transition from the Invisible Age, but its failure in connecting with the real LGBT community cast an ominous shadow as the gay activists themselves were preparing to use cinema as a tool for expressing their identity.

By the mid-to-late 1990s, the Korean LGBT movement became quite visible in two respects. First, the grass-roots organizers of various LGBT groups coalesced around an umbrella organization called Tong’inhyŏp (Korean Homosexual Human Rights Association) in 1995, which was expanded and renamed as Handonghyŏp three years later. True to its original name, Handonghyŏp put the human rights issue at the front and center, protesting discrimination against sexual minorities and advocating for their equal rights in legal and institutional terms. In so doing, however, the LGBT rights activists tended to downplay the distinctiveness of LGBT identities and cultures. This created a political/ideological tension within the movement, whose more radical members strove to raise fundamental questions about the heterosexual-male dominant social order and practice ‘sexual politics’(sŏng chŏngch’i) to overthrow it (Kim 1997, 120–123; Cho 2003; Seo 2001; 2005).

The latter strand of the movement, often personified by the prominent ‘gay intellectual’ Seo Dong-Jin (Sŏ Tong-jin), focused on cinema as an essential vehicle for its cause from the early years of the movement. Thus came the second moment of visibility of the Korean LGBT movement when Seo and his fellow activists attempted to host the first Seoul International Queer Film Festival at Yonsei University in September 1997. One of the main attractions of the festival was the immensely popular Hong Kong filmmaker Wong Kar Wai’s Happy Together (Chun Gwong Cha Sit, 1997), which the Korean government censorship had banned from public viewing. Whereas the censoring authorities had no problem passing another main feature—The River (He Liu, 1997) by Taiwanese director Tsai Ming-lyang—with arguably more explicit homosexual content, they probably deemed Happy Together too impactful since Leslie Cheung and Tony Leung, the two star actors who played a gay couple in the film, had been very much adored by the Korean public at large (Kang 1997; Lee 2006). Although the attempt to view the film in defiance of the ban was quashed by the university’s decision to literally pull the plugs on the theater, the entire spectacle of protests and public debates over ‘queer cinema’ served as a punctuation mark for the Invisible Age.

1To be sure, this kind of ‘first ever’ claim is almost always disputable at some level. The film magazine Cine21 argued that Kim Su-yong’s Starting Point (Sibaljŏm, 1969) could qualify as the first Korean film depicting homosexuality (Mun 2003). But in fact Sin Sang-ok’s Eunuch (Naesi, 1968) had already done just that a year earlier. 2The Housemaid trilogy refers to the original Housemaid (Hanyŏ, 1960), and the two versions of Woman of Fire (Hwanyŏ, 1971, 1982).

While the Happy Together debacle was causing a popular backlash against censorship, the protracted democratic transition of South Korea turned another corner with the election of President Kim Dae Jung, a long-time leader of the opposition Democratic Party. The combination of popular pressure and a new liberal government helped bring a more sympathetic policy to the LGBT community and relax ‘ethical’ standards for films and other artistic expressions. Consequently, the ban on Happy Together was overturned in 1998, and some daring filmmakers started testing the limits of sexual expression the new ‘viewer rating’ system had set instead of the old school censorship. Yellow Hair (Norang mŏri, 1999) and Lies (Kŏjinmal, 2000) were typical cases of such transgression that left the mainstream movie industry uneasy about taking on sexual taboos, including homosexuality, in the supposedly new era of democracy. This hesitance, compounded with a desire to translate such themes onto the silver screen, characterizes the Camouflage Age. Some mainstream films produced in the years between 1998 and 2005 have similar characteristics of fading their queer content into the background in order to avoid costly run-ins with either the viewer rating authorities or the homophobic conservatives. Memento Mori (Yŏgo koedam tubŏntchae iyagi, 1999) and Bungee Jumping of Their Own (Pŏnji chŏmp’ŭ rŭl hada, 2001) are two of the most successful films that adopted such camouflage.

A Latin term meaning ‘remember you will die,’ Memento Mori refers to a genre of art that serves to remind the viewers of their own mortality. This imagery of mortality paints a dark backdrop for the horror movie to play on. The romance that the horror revolves around is that of a lesbian couple in an all-girls high school. Two of the students, Si-ŭn and Hyo-sin, get involved in a romantic relationship with each other, only to be marginalized by the rest of the school. This causes Si-ŭn to publicly renounce Hyo-sin, leading to Hyo-sin’s suicide. The terror begins when Hyo-sin’s ghost haunts the school and eventually possesses another student who has found and read a shared diary between the two lovers; through this new, possessed girl Min-a, the first romance between Si-ŭn and Hyosin can revive and continue.

The film clearly plays up the homosexuality angle within a safe boundary, showing the two girls kissing on a few occasions and using delicate symbols of lesbianism (Kim and Pak 2005). However, as the directors Kim T’ae-yŏng and Min Kyu-dong stated in an interview, their intention to make it “a feminist movie or a queer movie” was not “communicated properly” to the majority of viewers, who probably did not expect such seriousness from the sequel of a prototypical schoolgirl horror film, Yŏgo koedam (Whispering Corridors, 1998). As a matter of fact, Min had been experimenting with the lesbian theme in his earlier short film Herstory (1996), with which he “wanted to make some kind of a [political] statement.” But with Memento Mori he concluded that “the most politically provocative way to deal with homosexuality is not to politicize it at all.”3

Regardless of the filmmakers’ intention, the particular genre selection of schoolgirl horror helps to soften the political edge by locating lesbianism in an all-girls high school setting, where romance between classmates or between upper-and lower-class girls is quite common and largely tolerated as a ‘rite of passage.’ Fantasies inherent in this type of horror film, such as ghosts, possession, and telepathy, also form a buffer zone from the intolerant realities. If the ero genre rendered the LGBT sexualities invisible, therefore, the horror genre gave only a glimpse of them in a heavy cover.

Equally full of fantasies but not of horror, Kim Tae-sŭng’s Bungee Jumping was received as more provocative than Memento Mori, at least by some film critics and academics Grossman and Lee 2005, 188; Cho 2009, 15–17). The first part of the movie tells the tragic love story of a young man named In-u and his girlfriend T’ae-hŭi. They quickly fall in love, but on the day In-u leaves to serve in the military, T’ae-hŭi is killed by a bus on her way to see him off. Skipping ahead seventeen years, the viewers now see In-u as a high school teacher married with children. The sad twist of fate arrives when In-u finds the reincarnation of his first love in one of his male students, Hyŏn-bin. In spite of himself, In-u begins to pursue Hyŏn-bin romantically, causing heavy grief in his own life. Hyŏn-bin, who hitherto has shown no hint of homosexuality, eventually reciprocates In-u’s feelings after initial apprehension. Leaving his family and losing his job, In-u seeks to continue his relationship with Hyŏn-bin, taking a trip to New Zealand together. While there, they decide to go bungee-jumping off of a cliff—without the bungee cords. In a parallel to the portrayal of the beautiful landscapes of New Zealand at the beginning of the film, In-u and his lover Hyŏn-bin/T’ae-hŭi plunge off the cliff hoping to be reincarnated as lovers once again, presumably in a more tolerant society that would accept their love.

As Anthony Leong points out, the film might have made some viewers “feel a sense of unease watching societal norms being trashed in the name of love, particularly since [Hyŏn-bin] offers a triple-whammy of lines being crossed, as he is (a) a teenage (b) male (c) student of [In-u]’s.” But it stops short of pushing this moral conflict further, and “ends up stumbling on its last step with a disappointingly contrived third act that tries too hard to please everyone” (Leong 2002, 142). Robert Cagle, on the other hand, devotes almost an entire chapter to analyzing Bungee Jumping in terms of sexual politics. He puts a finger on the contradictory strategy in that “the film finds ways of subsuming queer desires into a normative narrative of heterosexuality, the action merely serves to disavow them rather than negate them.” The film indeed has “a more progressive message, showing viewers that there is very little that separates heterosexual from homosexual relationships” and “does its best to break down widely held stereotypes that link male heterosexuality and femininity by focusing on characters whose behavior fits comfortably into (heterosexual) masculinity.” However, Bungee Jumping would probably not please the same gay activists who shunned Broken Branches, for it “bears the marks of two divergent desires—one to represent and one to repress homosexuality” (Cagle 2007, 286–287).

In a slightly oblique fashion, these two Camouflage Age films reflect the aforementioned political/ideological tension within the LGBT movement. The equal rights advocates, particularly those who worked at the first-ever Korean gay male organization Ch’in’gusai and later at Handonghyŏp as well, stressed the notion that gay men are not so different from heterosexual men. In other words, gays are pretty much ordinary folks except that they are, as the motto of Ch’in’gusai reads, “men who love other men.” This strategy of ‘different but equal’ masculinity did help dispel some of the worst prejudices and homophobia the Korean gay community had faced, even though its detractors argued that it contributed to the “normalization” of queerness and the increasing depoliticization of gay communities by painting sexuality as a “private” matter (Ch’oe 1996, 34–38; Cho 2003, 48–49; Seo 2005, 79–81). It is not too difficult to see a parallel between Bungee Jumping and Ch’in’gusai/Handonghyŏp with regard to their strategy to gain acceptance from the heterosexual majority. On the other hand, the ‘sexual politics’ crowd turned out to have delivered the government censorship a Memento Mori—reminder of mortality—in the form of the Happy Together debacle. Just like the film Memento Mori, however, their intention of upending the dominant heterosexual norms does not seem to have communicated clearly enough to the mainstream society, as their activities have gradually faded into obscurity since then.

If the preceding Invisible Age had only one very visible spot in Broken Branches, the Camouflage Age showed many uncovered patches. LGBT-themed short films by upstart, independent directors became a staple of the film festival circuit (Kang 2004; Grossman and Lee 2005, 182). The relationship between the independent film community and the LGBT groups was actually so tight that the secretary general of the Association of Korean Independent Film and Video (Han’guk Tongnip Yŏnghwa Hyŏp’hoe) gave a speech of support for the ‘Rainbow’ Queer Culture Festival in 2003. Outside the independent circles, there were some established ‘art house’ filmmakers whose works dabbled with homosexuality in varying degrees, such as Pak Ch’ŏl-su’s Bongja (Pong-ja, 2000), Song Il-gon’s Flower Island (Kkossom, 2001), and Kim Ŭng-su’s Desire (Yongmang, 2002). In the mainstream movie business, Kim Yong-gyun’s melodrama Wanee and Junah (Wa-ni wa Chun-ha, 2002) featuring a sideshow of a gay couple did reasonably well at the box office.

Camouflaged or not, the increasing LGBT presence in Korean cinema gave the impression that an openly ‘homosexual movie’ would soon make a splash at the mainstream box office. The most likely candidate to do so at the beginning of the new millennium was Road Movie (Rodŭ mubi, 2002), produced and distributed by big name majors in the business. Kim In-sik won several best new director awards for making this film, and the solid character actor Hwang Chŏng-min played a homeless gay man who fell into a strange love triangle involving another homeless man and a female prostitute. Hwang also won several best new actor awards for this role, raising the profile of Road Movie even higher. For all the glitz, though, it sold only about 16,000 tickets in Seoul’s theaters—a dismal number overall, and even less than one sixth of what Wanee and Junah took in. Regardless of its quality, Road Movie turned into a road block for the arrival of openly ‘homosexual blockbusters,’ at least for a couple of years.

3“People: Memento Mori co-directors, Kim T’ae-yŏng and Min Kyu-dong,” Cine21, January 6, 2000. http://www.cine21.com/Article/article_view.php?mm=005002002&article_id=33328 (last accessed on May 19, 2011).

The years surrounding 2005 witnessed a small victory for the LGBT rights groups, as the National Human Rights Commission—an independent government agency created to uphold democratic principles and protect constitutional rights for all citizens—drafted a comprehensive anti-discrimination bill (ch’abyŏl kŭmji pŏban) including a ‘sexual orientation’ clause, and officially recommended its legislation by the National Assembly. Quite predictably, a conservative backlash soon followed. The right-wing Christian organizations in particular have been relentlessly spearheading an all-out opposition with street protests, petition drives, picketing, legislative lobbying, and a series of daily newspaper ads warning of the ‘dangers’ of homosexuality since the announcement of the original bill. As a result, the anti-discrimination bill is still pending in the legislature after all the hoopla about dropping and then putting back in the sexual orientation clause over the years.

These are tell-tale signs of how conspicuous the topic of homosexuality has become in public discourse. And if the recent surge of homophobic campaign is any indication, it owes a great deal to the increasing media representation of LGBT cultures. For instance, the Korean TV network SBS ran into trouble when its openly gay-themed drama Life Is Beautiful (Insaeng ŭn arŭmdawŏ, 2010) became a target of the anti-gay newspaper ad that read: “My son turned ‘gay’ because of Life Is Beautiful; SBS should be held responsible if he dies of AIDS!”4 The latest and most daring for sure, but Life Is Beautiful was not the only one; such ‘trendy’ dramas as The First Shop of Coffee Prince (K’ŏp’i p’ŭrinsŭ ilhojŏm, 2007) and Personal Taste (Kaein ŭi ch’uihyang, 2010) had already picked up LGBT themes to spice up their main storyline of heterosexual romance (Hong 2008).

The homophobic paranoia that the TV medium is full of HIV-infected homosexuals actually has its roots in a decade-old incident involving an actor-broadcaster named Hong Sŏk-ch’ŏn. His public admission of homosexuality in 2000 was immediately scandalized, prompting his banishment from the broadcasting business. The LGBT movement rallied around Hong’s cause, and he was allowed back to the business three years later albeit in a reduced capacity. It was not only an inspiring human story especially for the LGBT community, but also a stinging exposé of the deep-seated sexual conservatism and hypocrisy in the Korean mass media. Nevertheless, there was a few years’ gap between Hong’s travail and the recent ‘queer drama’ boom, suggesting that something other than TV might have been also at work to bring out a sea change in public perception, more specifically ‘visual’ perception, of homosexuality and queerness.

Probably nothing had a bigger impact in this respect than The King and the Clown, the grand opening salvo of the Blockbuster Age of Korean queer cinema. The staggering box office number alone would impress anyone; over twelve million viewers, that is nearly a quarter of the entire South Korean population, set the new record at the time and still keep it ranked third in history. The King and the Clown swept virtually all major categories at Korea’s most prestigious Grand Bell Awards (Taejongsang), including the best director won by Yi Chun-ik.

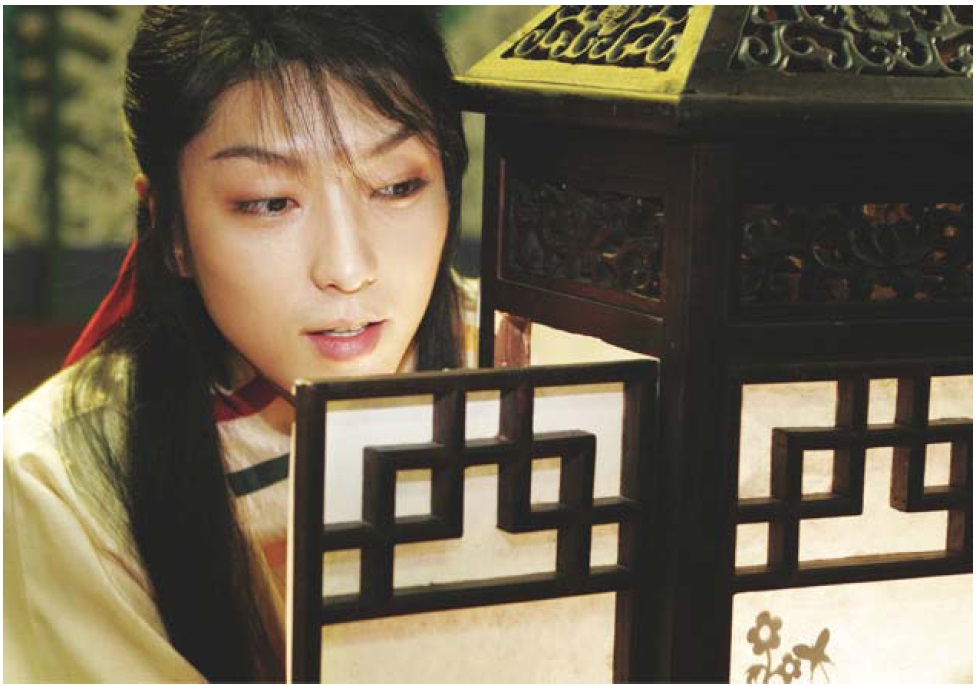

The movie plot revolves around the midong character named Kong-gil, played by the ‘prettier than female’ actor Yi Chun-gi. His masculine namsadang partner is Chang-saeng, with whom Kong-gil has had a sort of platonic relationship since their childhood. A series of luck, both good and bad, brings them in the royal court where the mentally and emotionally troubled King Yŏnsan—one of the two deposed ‘tyrants’ in Chosŏn history—spares their lives when Kong-gil manages to amuse him. As the namsadang troupe is kept to do its shows in the court, the king grows increasingly fond of Kong-gil to the point of having a sexual relationship with him. Apparently incensed by this turn of events, Chang-saeng insults the king and receives a death sentence for his offense. In the end, the love triangle between the three reaches a breaking point as political turmoil builds around the increasingly unhinged king.

To a certain extent, The King and the Clown’s commercial as well as critical success can be attributed to the compelling storylines, superb acting, and other such elements that usually make up a great film. But it was undoubtedly the ‘visual’ element that broke down the barrier of social taboo and turned homosexuality into the film’s strong attraction. As Darcy Pacquet points out, “Like many other instances of discrimination in modern-day Korea, aesthetics or appearance can sometimes write over prejudicial, ideological attitudes. This may not represent any progressive advance, but it wouldn’t surprise me if many young men who saw this film with their girlfriends spent time thinking about their inner reaction to Kong-gil.”5

While the film’s visual pleasure is hardly limited to Kong-gil’s midong character alone, there is no denying that he started the ‘gay man = gorgeous beauty’ formula now prevalent in Korean mass media, known as the ‘flower boy’ (kkonminam) phenomenon. The next two ‘homosexual blockbusters,’ Antique (Sŏyang koldong kwajajŏm aent’ik’ŭ, 2008) and A Frozen Flower (Ssanghwajŏm, 2008) followed the same formula, albeit not as successfully as The King and the Clown. The Memento Mori co-director Min Kyu-dong returned once again to the LGBT theme with Antique, a film derived from the Japanese yaoi (boys’ love) culture that caters to the sexual desires of the young female population by depicting a homoerotic relationship between two pretty boy characters in manga comics or amateur ‘fan fictions’ (Noh 2002; Lunsing 2006). Whereas Antique’s setting is a modern Korea where some young, well-to-do male professionals and college students pay attention to facial treatments and hair styling more than ever before, A Frozen Flower goes back to the medieval Koryŏ kingdom to find another troubled king who had a ‘flower boy’ lover. In both movies, the major male characters are all fabulously gorgeous, regardless of their sexual orientations.

The ‘flower boy’ phenomenon in the film and TV drama business has been heavily criticized for the fantasized, unrealistic representation of homosexuality that in effect alienates the LGBT community and their real-life issues; homosexual characters are often portrayed as oversexed, immature, or mentally unstable (Cho 2009; Lee 2009). But some of those who have studied the yaoi culture point to the subversive queerness of female sexuality at the roots of the ‘flower boy’ phenomenon, for whatever shortcomings it may have vis-à-vis the dominant male heterosexual desires (Hong 2008; Ch’oe 2009). The fact that the box office results of the latter two films were primarily driven by—presumably heterosexual— female viewership confirms that there is something more than just male-to-male sexuality in these ‘homosexual blockbusters.’ As sexual minorities, the LGBT community could not, and in all probability did not wish to, claim these movies as their own stories.

Even in the Blockbuster Age, therefore, queer films from LGBT perspectives are mostly found in the independent film circuit.6 In fact, two of the leading figures of Korean independent queer cinema are activists themselves, affiliated with the gay rights group Ch’in’gusai: Yi-Song Hŭi-il and Kim-Cho Kwang-su. The director Yi-Song’s debut short film, Everyday like a Sunday (Ŏnjena iryoil kach’i, 1997) was created in the heat of the censorship battle involving both the LGBT and the independent film community, and followed by a series of queer movie projects in the 2000s. Starting as a producer, Kim-Cho only recently turned to directing a couple of short films in cooperation with Ch’in’gusai.

Together, Yi-Song and Kim-Cho made their mark in Korean queer cinema with No Regret (Huhoehaji ana, 2006). The film sits in the gray area between the mainstream commercial world and the independent art world. Kim-Cho’s company, Ch’ŏngnyŏn Film, produced both independent and mainstream big box office movies, including the Camouflage Age hit Wanee and Junah. Thus they were able to have No Regret released nationwide by a major distribution company, even though the director and cast members were all from the obscure ‘indie scene’ and the production cost merely a 100 million won—a little more than 9,000 USD—in total. A savvy marketing plan targeting the female yaoi enthusiasts managed to create a dedicated fan base called Huhoep’yein (Regret-heads), who then carried out a word-of-mouth campaign to fill theater seats.7 Consequently, more than 44,000 people went to see No Regret, setting a record at the time for independent films. Some would joke that considering the relatively tiny number of theater screens it was on, No Regret is an ‘indie version of The King and the Clown’ in terms of viewership.

Obviously the two films are very different, not just in absolute numbers but in homosexual content as well. Whereas The King and the Clown shows no more than a kiss, No Regret has few qualms about brandishing highly charged acts, even one-upping the notorious opening scene of Road Movie. No wonder since “Be truthful to your libido” is the lesson to take away from No Regret in the director’s own words.8 Furthermore, underneath this surface of sexual explicitness No Regret has two layers of queer strategy that challenges the notion of heterosexuality as the established social norm, or as queer theorists call it, ‘heteronormativity’ (Warner 1991; Weiss 2001). If The King and the Clown gently asks for tolerance, No Regret loudly demands recognition.

The first layer of queer strategy in No Regret is “naturalization” of homosexuality. According to Ch’oe Sŏn-yŏng, whose master’s thesis consists of a detailed analysis of the film, “the main characters of No Regret show no sign of doubt about their sexual orientation; feel neither shame nor guilt about their homosexuality. Just as heterosexuality is considered biologically natural in the romance film genre, No Regret adopts the strategy to make homosexuality look innate and natural” (Ch’oe 2009, 38). At this level, it is not unlike Chin’gusai’s strategy of ‘different but equal’ masculinity as discussed previously. The film starts encroaching on heteronormativity when it lays the second layer of queerness on top of the “men love other men” storyline, by borrowing the narrative structure of the so-called ‘hostess film’ and giving it a twist.

As a precursor and later subgenre of the aforementioned ero yŏnghwa in the 1980s, the hostess film genre typically follows the trajectory of an innocent young girl from a poor rural village ending up as a broken-down prostitute in the big city. Su-min, the poor orphan character who ends up working as a male host, takes the central role in the sex-changed hostess film narrative of No Regret. Pursuing him romantically is Chae-min, an heir of a wealthy family, who is about to have an arranged marriage with a woman. Unlike the heterosexual narrative where the woman goes through “sexual degradation” of becoming a hostess while her male lover suffers few consequences, the gay host Su-min, by virtue of being male, does not bear the same kind of moral burden. Rather, it is Chae-min who feels the burden of family loyalty, as he is being pushed into marriage by his mother even after admitting his homosexuality to her. In this way, the homosexual parody of the hostess film upsets the heterosexual code of moral judgment biased in favor of males (Ch’oe 2009, 48–52).

The film is full of genre clichés that highlight the class divide within the hostess romance narrative. For example, Su-min rebukes Chae-min’s indecisiveness, saying “A rich man like you may have many places to hide, but I have none.” It does not, however, follow the genre convention to the end, where the life of the lower-class female prostitute is destroyed over the remorseful tears of her upper-class male ex-lover. As the movie title suggests, there appears to be no regret on either side as Chae-min and Su-min go through the final tumult together. While this ending may look like another cliché from a romance drama, it actually completes the subversion of the hostess, and furthermore the ero genre, affirming LGBT sexualities to the fullest without pleasing the voyeuristic eye of male heterosexuality. If anything, such an eye would be harassed by the sight of gay bathhouses (tchimjilbang) and host bars throughout the film.

4Hankyore, October 29, 2010, http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/society/society_general/446342.html (accessed on May 19, 2011). 5“King and the Clown,” last updated on November 15, 2008, http://koreanfilm.org/kfilm05.html #kingandclown. 6Like a Virgin (Ch’ŏnhajangsa Madonna, 2006), a brilliant, witty film about a transgender highschool boy, might be considered a rare exception, yet even this one is not free from the suspicion of “beautifying” queerness for the sake of mainstream acceptance (Ch’oe 2009, 45).. 7“A Problematic Queer Film, No Regret,” Cine21, November 14, 2006. http://www.cine21.com/Article/article_view.php?mm=005001001&article_id=42650 (last accessed on May 19, 2011). 8Ibid.

It has been a long time coming both for Korean queer cinema and the LGBT community since the obscure, highly experimental films and the dark theater rooms of Nagwŏndong in the 1970s. From the mid-1990s on, the solidaristic alliance between the independent film and the LGBT communities started removing the veil of invisibility by fighting against the censorship and promoting LGBT-themed films. For the next ten years or so, the mainstream movie industry took some baby steps, forward and backward, testing the marketability of ‘homosexual films’ in various disguises. When it finally concocted the right formula in the ‘beautification’ of queerness, the floodgate was open; now we suddenly find ourselves in a rush of big box office movies and serial TV dramas starring ‘flower boys,’ no matter how vaguely gay they are in fiction or in reality. Meanwhile, the indie circuit’s steady production of LGBT films did reap some benefit from the public attention generated by the mainstream blockbusters. Its cutting-edge work attempts to combine LGBT equal rights and challenges toward heteronormativity, which looks like a noble yet daunting task.

This is a brief synopsis of Korean queer cinema thus far, and we put down our markers to divide it into three periods: the Invisible Age, the Camouflage Age, and the Blockbuster Age. We also tried to show how some of the representative works followed or bent the genre conventions of ero and horror films in characterizing each period. Having reviewed the past, we have a little bit of confidence in predicting that independent queer cinema will continue on strong, supported by the dedicated viewership of a respectable size, ranging from the yaoi women (tong’innyŏ) to the LGBT groups to independent film buffs. As for the future of the Blockbuster Age, it may end relatively soon if the ‘flower boy’ phenomenon turns out to be a transient fad, but no one would be so sure after spending one of these weekends flipping through various TV entertainment programs.