여가제약에 대한 이전의 연구들은 여가제약이 존재함에도 불구하고 참여가 이루어진다는 것을 증명하기 위하여 노력하였다. 본 연구는 여가제약이 협상을 통하여 극복될 수 있고 여가제약이 존재함에도 불구하고 어떻게 참여가 이루어지는가를 결정하는 것이 여가동기라는 것을 증명하는 연구들의 후속과정으로 이루어졌다. 그동안 이러한 과정을 설명하기 위해 여러 가지 모델들이 개발되었다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 참여의 결과론적인 변인들 속에 존재하는 변화에 대한 실질적인 관심이 부족하였다. 따라서 본 연구는 한국의 스포츠 센터 참여자(298명)들의 레크리에이션 전문화 구조를 바탕으로 여가제약 협상 과정이 레크리에이션 관여 정도에 따라 차이가 발생하는가를 규명하고자 하였다. 이전의 연구에서 사용된 다양한 모델을 검증하고 비판적 관점에서 이러한 모델들을 재조명하는 과정에서 여가제약 협상과정은 대부분 레크리에이션 전문화수준이 높은 경우에 보다 활발하게 이루어진다는 것을 발견하였다. 본 연구의 결과는 여가제약 협상 모델을 발전시키고 여가활동 범위와 관여수준을 보다 구체적으로 이해하는데 중요한 자료가 될 것이다.

Individuals often encounter difficulties that prevent them from participating in leisure activities. Many surmount these problems and barriers and in turn initiate the desired leisure activities while others do not overcome the barriers and give up the intention to participate in the activities, perhaps turning to alternatives that are more available to them. These different decisions may be entirely a function of particular circumstances, but they may also result from different levels of motivation and commitment to particular activities. In particular, persistence in spite of constraints may be more common among those who have devoted themselves to the activities in the past. Examining relationships among leisure constraints, motivation, negotiation and recreation specialization may thus provide insight into leisure-related decision making.

Many researchers have investigated the nature of constraints on leisure participation (e.g., Crawford, Jackson, & Godbey, 1991; Jackson, Crawford, & Godbey, 1993; Kay & Jackson, 1991; Scott, 1991; Shaw, Bonen, & McCabe, 1991). From the “constraint negotiation” perspective leisure constraints are regarded as barriers to be surmounted for participation (e.g., Alexandris, Kouthouris, & Girgolas, 2007; Frederick & Shaw, 1995; Henderson, Bedini, Hecht, & Schuler, 1995; Hubbard & Mannell, 2001; Son, Kerstetter, & Mowen, 2008). Within the leisure constraint negotiation process, motivation is regarded as an important determinant of successful negotiation (Alexandris et al., 2007; Alexandris, Tsorbatzoudis, & Grouios, 2002; Carroll & Alexandiris, 1997; Crawford & Jackson, 2005; Hubbard & Mannell, 2001; Loucks-Atkinson & Mannell, 2007; Son et al., 2008). While these studies have all been concerned with the relationships among constraints, motivation, negotiation, and participation (e.g., Alexandris et al., 2007; Hubbard & Mannell, 2001; Loucks-Atkinson & Mannell, 2007; Son et al., 2008), their findings have differed to some extent; and they have not addressed differences in activity involvement and commitment. For this reason, these relationships should be investigated further in various leisure settings and with specific attention to their application at different levels of involvement.

Once people have participated in a certain recreational or leisure activity, their levels of interest in and commitment to the activity change over time according to a variety of factors such as their relationships with other participants, the acquisition of necessary or advanced skills and knowledge, family support, their physical condition, and so on. Some remain committed to the activity, whereas others become less committed and eventually give up and try to find another activity. In the same vein, Bryan (2001) concluded that recent empirical leisure studies concerning specialization demonstrate that while some participants do progress to more specialized stages of activity, most people probably do not. It might be assumed that such specialization - or the lack thereof - is influenced by leisure constraints, motivation, and negotiation and further, that once specialization occurs, the interpretation of constraints and the willingness to negotiate them will be influenced accordingly.

Many studies have investigated the relationships among constraints, motivation, negotiation, and participation in recreation and/or leisure activities (Alexandris et al., 2007; Alexandris, Tsorbatzoudis, & Grouios, 2002; Carroll & Alexandiris, 1997; Crawford & Jackson, 2005; Hubbard & Mannell, 2001; Loucks-Atkinson & Mannell, 2007; Son et al., 2008), yet no empirical studies have been conducted on the relationships among leisure constraints, motivation, negotiation, and recreation specialization. Furthermore, many researchers have demonstrated that negotiation serves as a mediator between constraints and motivation, and participation (Alexandris et al., 2002; Alexandris et al., 2007; Carroll & Alexandris, 1997; Hubbard & Mannell, 2001; Son et al., 2007), while there has been no published article on the relationship between negotiation and recreation specialization. Because recreation specialization can happen only when participation occurs and continues for some time, it could be expected that constraints, motivation, and negotiation are related in some way to recreation specialization. Especially, Therefore, the primary purpose of this study was to test the competing models with leisure constraints, motivation, negotiation, and recreation specialization. Furthermore, the relationships among constraints, motivation, negotiation, and recreation specialization in recreation and/or leisure activities, and the mediation role of negotiation in the relationship between constraints and motivation, and recreation specialization were examined.

>

Negotiation of Leisure Constraints

Generally, leisure constraints are regarded as factors that prevent or limit participation in leisure activities (Crawford & Godbey, 1987; Crawford et al., 1991). Crawford and Godbey (1987) depicted three main types of constraints: intrapersonal, interpersonal, and structural. Before Crawford et al. (1991) and others (e.g. Kay & Jackson, 1991; Shaw, Bonen, & McCabe, 1991) suggested that constraints do not always keep or reduce participation, the general concept of leisure constraint had been regarded as an obstacle preventing people from participating in a certain leisure activity. And then, Jackson et al. (1993) argued that “leisure participation is dependent not on the absence of constraints (although this may be true for some people) but on negotiation through them”(p. 4). Such negotiations may modify rather than foreclose participation.

It is predictable that all participants encounter constraints at one time or another, and it is also reasonable to expect that constraints are negatively related to participation (Carroll & Alexandris, 1997; Loucks-Atkinson & Mannell, 2007; Raedeke & Burton, 1997). However, numerous researchers have recently asserted conceptually and empirically that constraints could be overcome through the negotiation process toward participation in leisure activities (e.g., Coble, Selin, Erickson, 2003; Frederick & Shaw, 1995; Henderson et al., 1995; Henderson & Bialeschki, 1993; Hubbard & Mannell, 2001; James, 2000; Livengood & Stodoloska, 2004; Son et al., 2008). For example, Henderson et al. (1995) found that women with disabilities utilized the negotiation strategies to resist gender role expectations and to become involved in leisure activities. Frederick and Shaw (1995) found that female aerobic participants used negotiation strategies to overcome their constraints; however, they did not measure the participants’ specific negotiation strategies.

In refining the measurement of constraint negotiation, Hubbard and Mannell (2001) demonstrated that employees providing recreation services facilitated their participation in leisure activities by using negotiation strategies. In their study testing four competing models of the interrelations among leisure constraints, motivation, negotiation efforts, and participation, they measured negotiation resources by asking 35 questions which included four types of negotiation resources: time management, skill acquisition, interpersonal coordination, and financial resources and strategies. In their study, constraints were found to lower the level of participation. However, constraints also triggered the use of negotiation strategies, which in turn increased participation. In addition, Loucks-Atkinson and Mannell (2007) tested the constraints negotiation process among individuals with fibromyalgia and found that the constraints decreased participation in leisure activities but also launched the use of negotiation strategies, and finally increased participation, a finding that is consistent with Hubbard and Mannell’s (2001) study. These two studies (Hubbard & Mannell, 2001; Loucks-Atkinson & Mannell, 2007) provided strong evidence of the mediation role of negotiation in the relationship between constraints and participation. However, in contrast with those studies, Son et al (2008) failed to find evidence that negotiation mediates the relationship between constraints and participation. Further investigation of the mediating role of negotiation in the relationship between constraints and participation is clearly needed, preferably in a variety of leisure settings.

>

The relationship between Motivation and Negotiation

As previously noted, Hubbard and Mannell (2001) tested a series of models among constraints, motivation, negotiation, and participation. This study found that motivation impacted participation in physically active leisure activities only indirectly through its positive effect on negotiation. However, motivation did not influence participation directly. In addition, when Loucks-Atkinson and Mannell (2007) tested a similar series of models incorporating constraints, motivation, negotiation, and participation with individuals who had fibromyalgia, their results were consistent with Hubbard and Mannell’s (2001) findings; neither study found support for a direct effect of motivation on participation.

On the other hand, Alexandris et al. (2007) investigated the relationship between motivation (both intrinsic and extrinsic), negotiation, and intention to continue participation in a leisure activity (skiing). Unlike previous studies, the results of their study revealed that motivation significantly and directly influenced intention to continue participation. More specifically, intrinsic motivation impacted intention far greater than did extrinsic motivation. Motivation also partially influenced negotiation; in turn, negotiation impacted intention. For testing the mediation role of negotiation on a link between motivation and intention, it was found that negotiation partially mediated the relationship between only intrinsic motivation and intention. Additionally, Son et al.’s (2008) study indicated that negotiation partially mediated the relationship between motivation and participation, which supported Alexandris et al.’s (2007) finding.

The term

One of the most important facets of recreation specialization is about progression rather than experience. Over more than 25 years, there have been many studies testing and arguing the measurement and theory of recreation specialization. Some researchers measured recreation specialization using only the behavioral dimension (Ditton et al, 1992; Donnelly, Vaske, & Graefe,1986), some only utilizing attitudes (McIntyre, 1989; Shafer & Hammit, 1995), and others using both behavioral and attitudinal dimensions (Bricker & Kerstetter, 2000; Kuentzel & McDonald, 1992; Virden & Schreyer, 1988). McIntyre and Pigram (1992) and Scott and Shafer (2001b) proposed three dimensions of recreation specialization: behavior, skill and knowledge and commitment. Recently, McFarlane (2004) used three dimensions (affective, behavioral, and cognitive dimensions) to measure recreation specialization in the context of a vehicle-based camp site. Additionally, Thapa, Graefe, and Meyer (2006) supported these measurement dimensions of recreation specialization in their study testing marine-based environmental behaviors.

Because recreation specialization is regarded as a continuum of behavior (Bryan, 1977; Scott & Shafer, 2001a), segmenting recreation specialization has been essential to conduct empirical studies. In this regard, Ditton et al. (1992) conceptually segmented recreation specialization into four groups: orientation, experiences, relationships, and commitment. With these four groups, Salz, Loomis, and Finn (2001) tested these segmentations with anglers. Scott, Ditton, Stoll, and Eubanks (2005) proposed three generic styles of participation within the specialization continuum: casual, active, and serious. Oh and Ditton (2006) generated three dimensions of the recreation specialization levels -- casual, intermediate, and advanced.

As previously noted, many researchers deliberated upon how to measure recreational specialization and how to segment the levels of specialization and arrived a better degree of specification as a result. This paper suggests that relationships among leisure constraints, motivation, negotiation, and recreation specialization may be equally as instructive. Previous studies have demonstrated the influence of leisure constraints, motivation, and negotiation on participation. However, no study has explored the effects of the above factors on recreation specialization with exceptions of Hwang (2010) and Hwang, Choi, & Han (2010)’s studies recently published in Korea. These articles indicated that leisure constraint negotiation positively influenced recreation specialization. It is expected that this study will be useful for understanding the complex relationships among factors that influence recreation specialization.

The survey population frame included recreational participants who had memberships with sport centers in Seoul, Korea. A cluster random sampling method was utilized (50 participants from each of six randomly selected sport centers). Specifically, all sport centers in Seoul were alphabetically numbered and six centers were selected using the table of random numbers. Paper-and-pencil surveys were distributed to 300 leisure participants and returned directly to the survey administrators. In this study, three leisure activities, namely body building, aerobics, and swimming activities (100 participants from each activity) were selected due to the popularity of the selected leisure activities. After excluding two incomplete surveys, the final sample size was 298. The ages of the respondents ranged from 20 to 69, with an average age of 35. The sample was 51.4% male and 48.6% female. The average monthly income was 2,250,000 won.

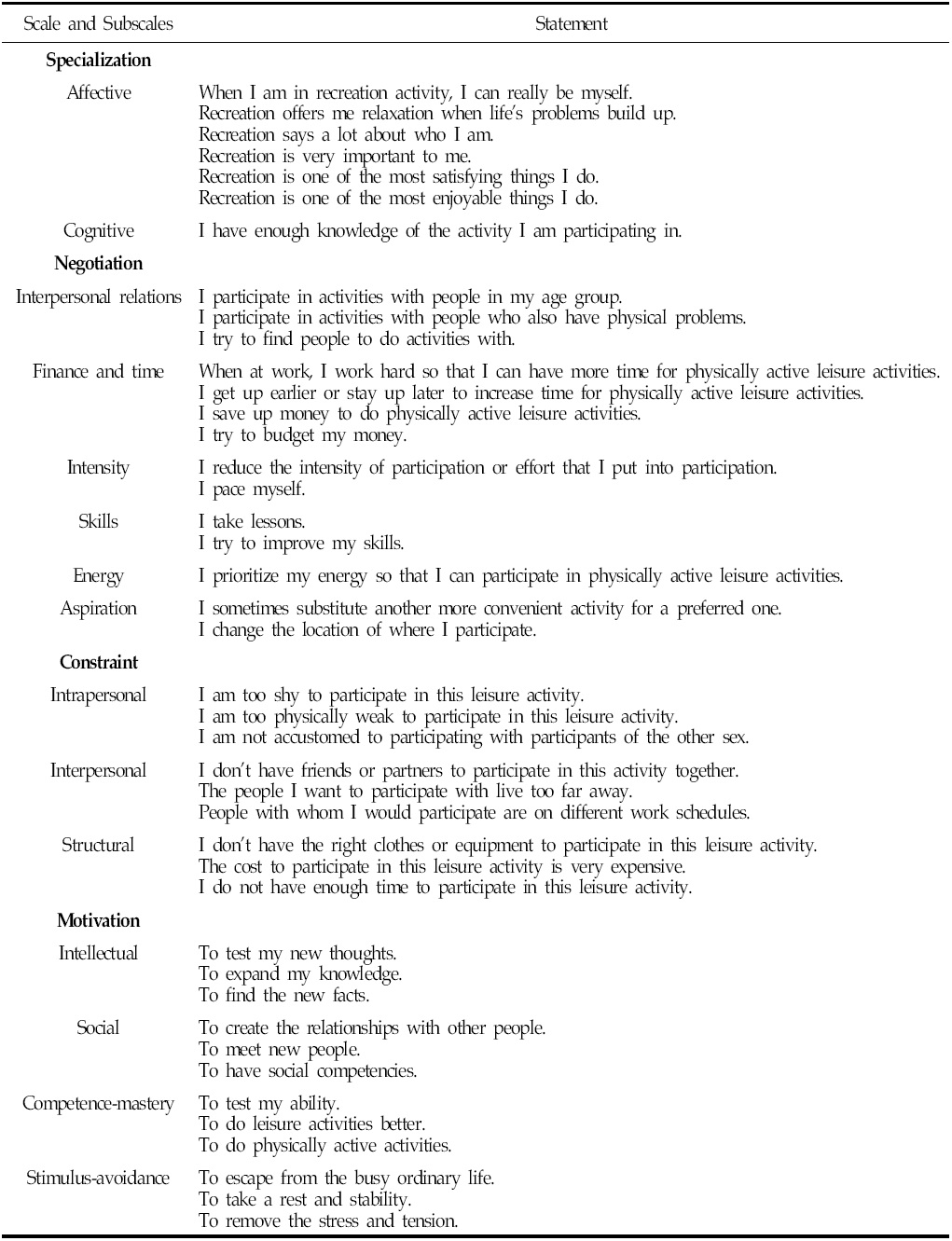

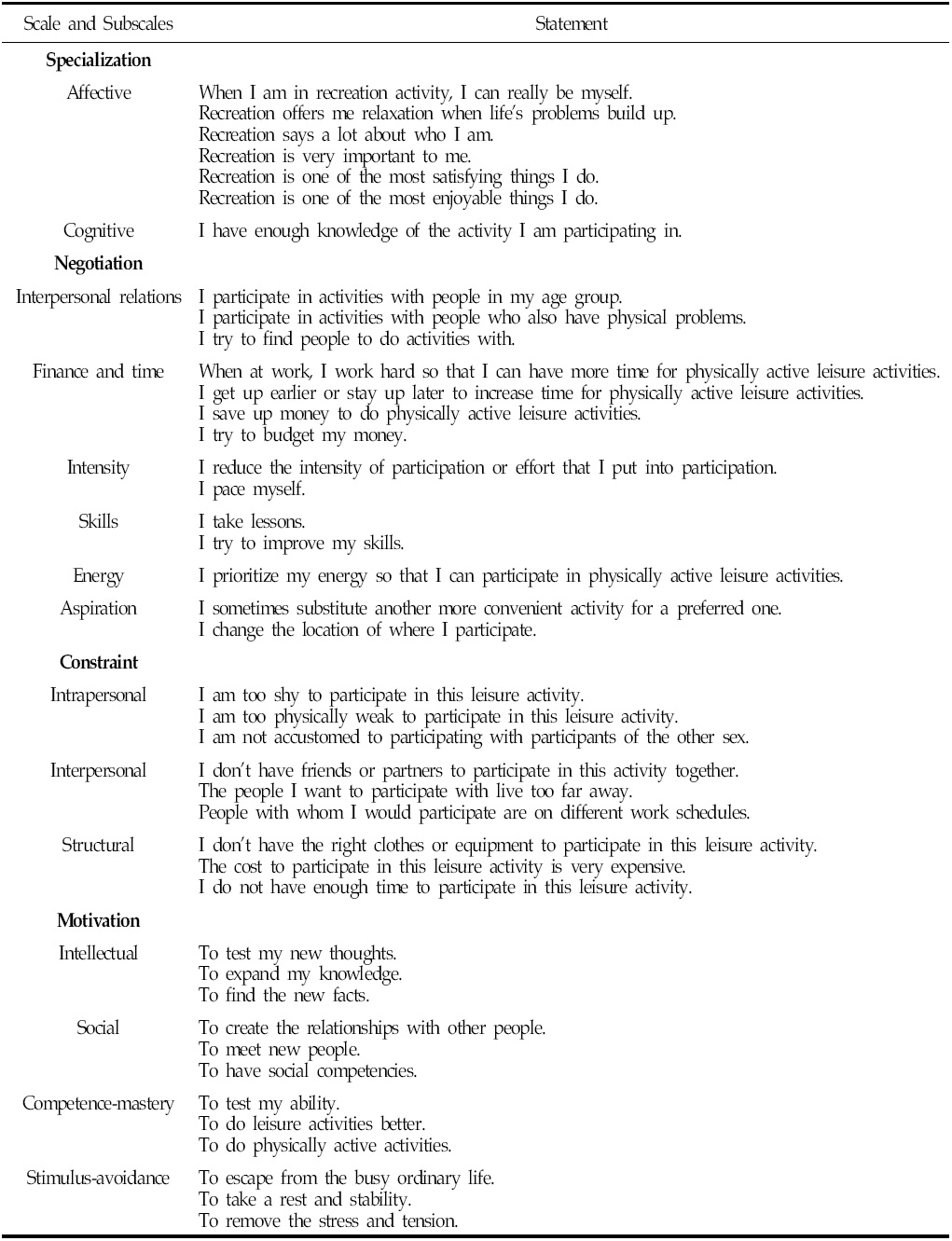

Recreation Specialization. The extent of recreation specialization was assessed using 13 items tapping three specific aspects (i.e., affective, cognitive, and behavioral specialization) of the recreation specialization developed by McFarlane (2004). Specifically, affective specialization was assessed using 12 items focused on three specific areas of the affective specialization as identified by McFarlane (2004). The specific areas were: (a) attraction (6items), (b) centrality (4items), and (c) importance (2items). Cognitive specialization was measured using a single item (see Table 1). Respondents answered affective and cognitive items on a 5-point scale. Behavioral specialization was measured by three open-ended items asking the frequency, duration, and intensity of leisure participation but these behavioral specialization items were excluded as the factor loading value from CFA was .26. The overall Cronbach’s alpha score for the recreation specialization scale was .92.

Negotiation. Loucks-Atkinson and Mannell (2007) tested the constraints negotiation process among individuals with fibromyalgia using 37 negotiation strategies stemming originally from Jackson and Rucks’ (1995) behavioral strategies. These strategies consisted of six types: changing leisure aspirations (5 items), improving finances (4 items), changing interpersonal relations (6 items), pain coping strategies (10 items), skills acquisition (3 items), and time management (9 items). Based on these indicators, Kim, Hwang, and Won (2008) developed the leisure constraints negotiation measurement scale for Koreans. In this study, to assess negotiation, a total of 24 items from Kim et al.’s (2008) scale were used to measure the level of agreement on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = Not at All and 5 = Very Much). This scale included six types of negotiation strategies: changing interpersonal relations (6 items), improving finance and time management (7 items), controlling intensity of an activity (3 items), skills acquisition (3 items), charging energy (2 items), and changing leisure aspiration (3 items). See Table 1 for exemplary items used in this study. The Cronbach’s alpha scores for the negotiation scale were .76, .81, .79, .77, .68 and .79 respectively.

Constraints. A total of 28 items were used to measure constraints to leisure activities developed by Hubbard and Mannell (2001): 11 items assessed intrapersonal constraints (e.g., I am too shy to participate in this leisure activity); 7 items assessed interpersonal constraints (e.g., I don’t have friends or partners to participate in this leisure activity together); and 10 items assessed structural constraints (e.g., I don’t have the right clothes or equipment to participate in this leisure activity). Responses were made using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha scores for three constraints were .83, .80, and .78 respectively.

[Table 1.] Examples of Items from the Specialization, Negotiation, Constraint and Motivation Scales

Examples of Items from the Specialization, Negotiation, Constraint and Motivation Scales

The SPSS 16.0 package was used for reliability and correlation analyses among variables. AMOS 5.0 was used to test competing models including the independence model, the constraint-effects-mitigation model, and the perceived-constraint-reduction model (cf. Hubbard & Mannell, 2001). In the Hubbard and Mannel’s (2001) study, it was determined that there was no moderating effect of negotiation on the constraint-participation relationship which indicated that the negotiation-buffer model was not appropriate. through the hierarchical regression analysis. For this reason, the negotiation-buffer model was excluded in this study.

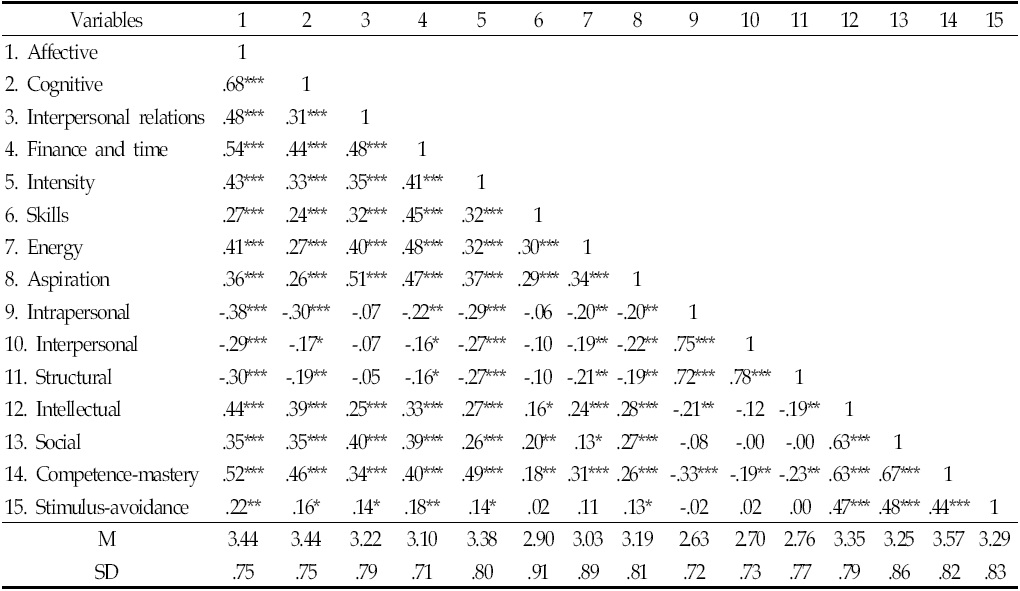

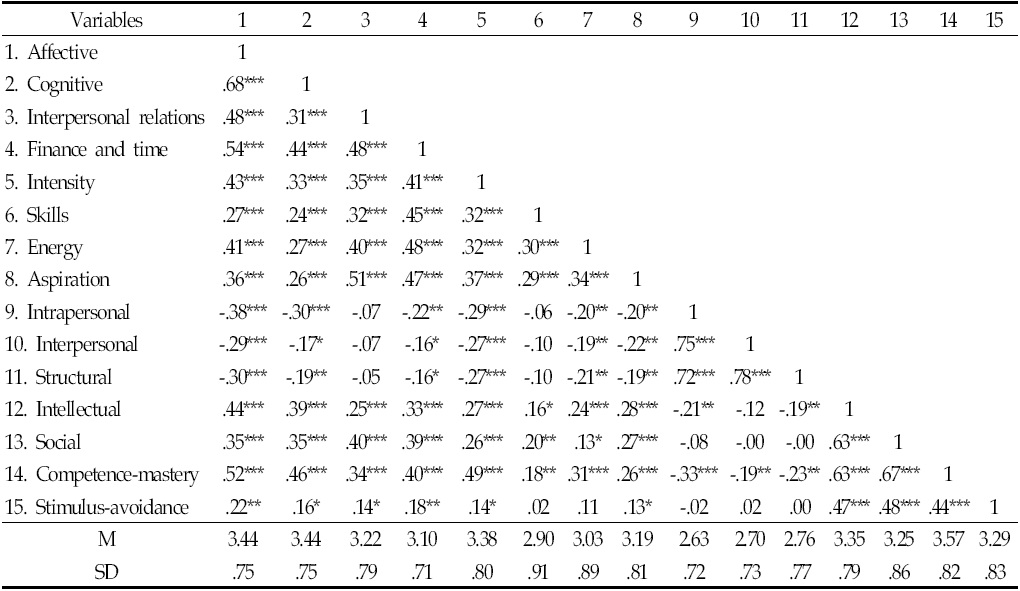

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations of Recreation Specialization, Negotiation, Leisure Constraint, and Motivation

>

Correlations among Variables

In the present study, a correlation analysis using the average scores of the measurement variables was conducted prior to the test of the structural model of the recreation specialization process. According to Table 2, there were significant correlations between leisure constraints, leisure motivation, leisure constraints negotiation, and recreation specialization. Particularly, it appeared that intrapersonal, interpersonal, and structural constraints had negative correlations with leisure motivation, leisure constraints negotiation, and recreation specialization. Regarding the average scores, the affective (3.44) and cognitive (3.44) dimensions of recreation specialization were relatively high. The average scores of all dimensions of leisure constraints negotiation were greater than 3.03 with the exception of skills acquisition (2.90). The average score of leisure constraints was 2.75 and the average scores of all motivation dimensions were higher than 3.25, which were somewhat high.

>

Testing the Structural Models of the Negotiation Process for Recreation Specialization

The structural equation modeling method using AMOS 5.0 was employed to test the structural model. Since Hubbard and Mannell (2001) found no moderating effect of negotiation on the constraint-participation relationship, the negotiationbuffer model was not tested. Only the independence, constraint-effects-mitigation and perceived-constraintreduction models were tested in the current study.

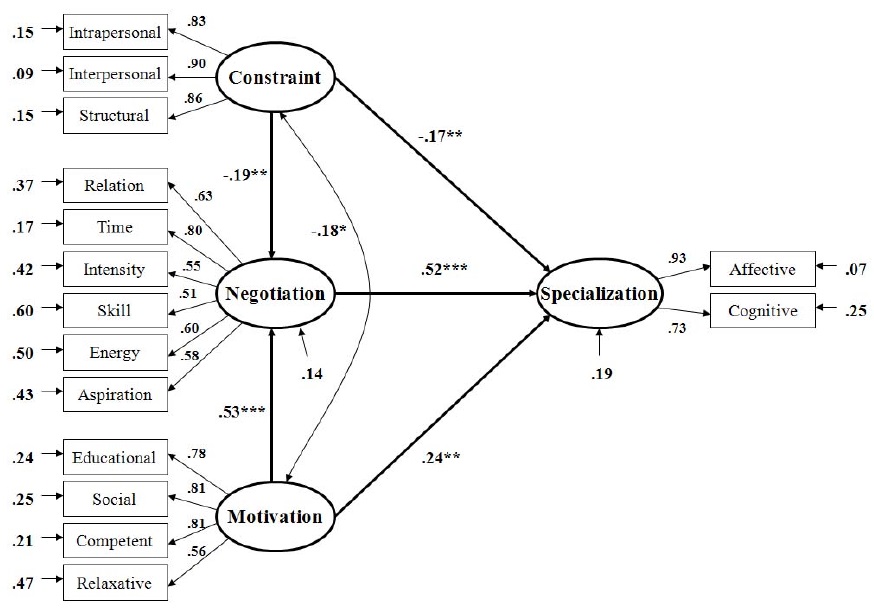

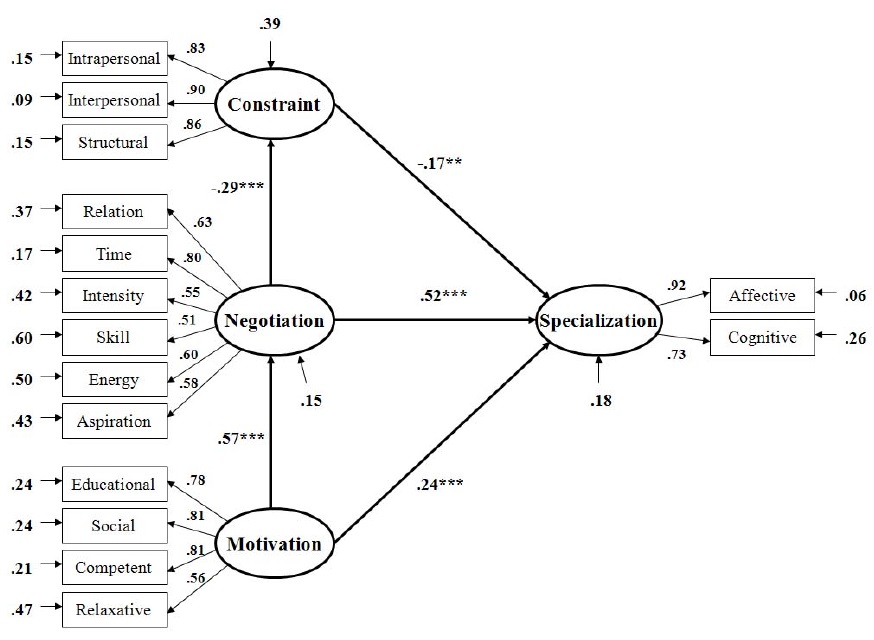

In the independence model of the negotiation process for recreation specialization, constraints, negotiation, and motivation were put as exogenous variables, and recreation specialization as an endogenous variable. It assumed that there are correlations among exogenous variables. Factor loading values of constraint, negotiation, motivation, and recreation specialization in the measurement model were greater than .40, which indicated multi-dimensional subfactors. As shown in Figure 1, negotiation (

In the constraint-effects-mitigation model of the negotiation process for recreation specialization, constraint and motivation were placed as exogenous variables, and negotiation and recreation specialization as endogenous variables. As shown in Figure 2, constraint (

In the perceived-constraint-reduction model of the negotiation process for recreation specialization, motivation was put as an exogenous variable, and negotiation, constraint, and recreation specialization were placed as endogenous variables. The structural flow of this model indicates that not only did motivation have a direct effect (

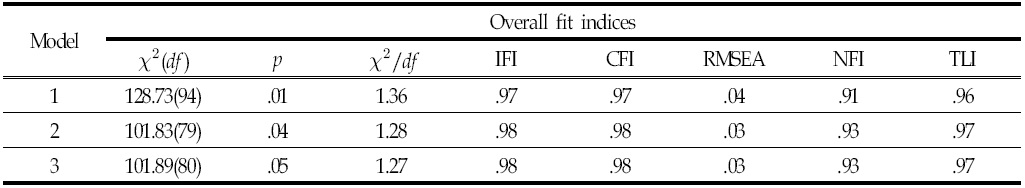

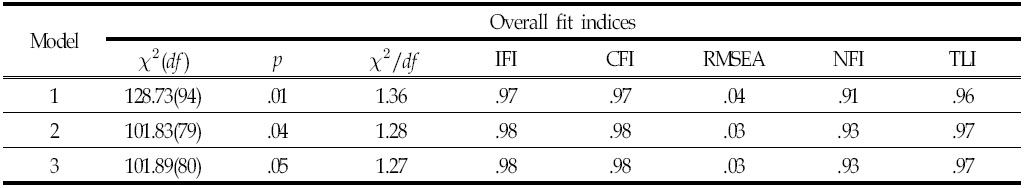

The results of testing the goodness-of-fit of the structural models were shown in Table 3. According to Hu and Bentler (1999), there are three kinds of model fit indices: an absolute fit index, an incremental fit index, and a parsimonious fit index. It is recommended to provide at least one specific model fit index of each kind of index to identify the model fit. In the present study, the following model fit indices were used: the ratio of the chi-square statistic to the degree of freedom (X²/

[Table 3] Summary of Overall Fit Indices for the Three Models

Summary of Overall Fit Indices for the Three Models

The model fit of the independence model (Figure 1) shown in Table 1 describes that the chi-square was statistically significant at the level of

model had a better model fit. Regarding the fit of the perceived-constraint-reduction model (Figure 3), the chi-square was not statistically significant at the level of

The authors constructed competing models of the recreation specialization process based on Hubbard and Mannell’s (2001) study and then tried to identify which was the best model for explaining the recreation specialization process. In addition, the relationships among the variables within these models were tested. To extend the process provided by Hubbard and Mannell (2001) to recreation specialization beyond participation, the participation variable in their models was replaced by the recreation specialization variable. The results of the present study revealed that the fit of the recreation specialization process model was increased in contrast to Hubbard and Mannell’s (2001) and Loucks-Atkinson and Mannell’s (2007) models. However, there are some limitations. In this study, since the subjects were limited to participants in the recreation programs presented by sport centers, there was a limitation to generalize the results of the study. Furthermore, since the behavioral dimension of recreation specialization had a somewhat low factor loading value with .26 resulting from the CFA, the dimension was excluded in this study. So, we are unable to discuss the behavioral dimension of recreation specialization.

In spite of these limitations, the current study was meaningful and informative because the leisure constraint negotiation process has been further clarified. Hubbard and Mannell (2001) contributed not only to understanding the nature of leisure behavior by identifying the roles of motivation and negotiation within the leisure constraint negotiation process for participation in leisure activities but also by extending the aspects of the leisure constraint negotiation process in subsequent studies (e.g., Loucks-Atkinson & Mannell, 2007). The current study extends this work still further.

Furthermore the current study improved on earlier research in adhering more closely to basic assumptions for establishing research models. Structural equation modeling should put the logical relationships among latent variables (constraint, motivation, negotiation, and participation) into the form of a diagram. In SEM, the latent variables should appear as the circles and the measurement variables should be described as the squares. In previous studies, the relationships between the latent variables (constraint, motivation, and negotiation) and the measurement variable (participation) were investigated, but methodologically, the participation variable should have been placed as a latent variable (circle) connected with the measurement variables. In the case that the latent variable was a single dimension, this variable would be a latent variable and a measurement variable. Second, the latent variables did not contain the measurement errors. The measurement errors of the latent variables should appear because these could be very important indicators to indirectly infer the power of explaining variable. The last problem concerns the direction in the relationship between constraint and negotiation. Hubbard and Mannell’s (2001) study showed the positive effect of negotiation on constraint. This result is not consistent with Jackson et al.’s (1993) proposition that “variations in the reporting of constraints can be viewed not only as variations in the experience of constraints but also as variations in success in negotiating them” (p. 6). According to Jackson et al. (1993), since sufficient negotiation resources would result in fewer constraints, negotiation should have had a negative effect on constraint.

In order to overcome the problems mentioned, the authors made the following efforts to generate meaningful results in the present study. First, a participation variable placed as a square in Hubbard and Mannell’s study was replaced with a recreation specialization variable as a latent variable (circle) linked with two measurement variables (square) including affective and cognitive dimensions. Second, measurement errors of the latent variables were considered. Finally, there was the negative relationship between leisure constraint and negotiation variables, which means that participants may experience difficulty with negotiation as leisure constraints increase and that leisure constraints may decrease as the ability of participants to negotiate increases.

>

Fit of Negotiation Process Model to Recreation Specialization

All three models proposed in the present study had adequate model fits such as an absolute fit index (chi-square and RMSEA), an incremental fit index (NFI and TLI), and a parsimonious fit index (IFI, CFI, and NCM). However, the perceived-constraintreduction model had the most acceptable model fit, followed by the constraint-effects-mitigation model and the independence model. The model fit of the perceived-constraint-reduction model was very similar to one of the constraint-effects-mitigation model, but the former had the better probability (p) and the normed chi-square measure(NCM) than the latter. This indicates that the perceived-constraint-reduction model accounted best for the negotiation process affecting recreation specialization in this context.

The most important finding in the present study is that the perceived-constraint-reduction model had a better model fit than the others. However, Hubbard and Mannell (2001) asserted that the constrainteffects-mitigation model had a better model fit (NCM=1.62, IFI=.96, CFI=.95, RMSEA=.06, NFI=.89, TLI=.94) than the other models. Comparing the results of the present study with those of previous studies, the model fit of both the independence and the constraint-effects-mitigation models were increased from that in the Hubbard and Mannell’s study. This may have resulted from the establishment of the measurement variables for the latent variable (recreation specialization). In other words, Hubbard and Mannell (2001) put participation as a single measurement variable, but we placed recreation specialization as a latent variable with multidimensions. However, there is still a limitation of these models because the behavioral dimension of recreation specialization was excluded. In contrast to the affective and cognitive dimensions of recreation specialization, the behavioral dimension was measured by open-ended questions. Generally, this can cause deterioration of the validity of the construct when employed with the Likert-type scales simultaneously. Accordingly, it is essential that a more suitable measure of the behavioral dimension for recreation specialization be developed to advance the recreation specialization-related model.

>

The Role of Motivation in the Negotiation Process

The term recreation specialization was coined by Bryan (1977) and, although many researchers in the recreation and leisure study area have been interested in it for over 30 years, it has still been controversial with respect to concept, measurement, and effectiveness (Scott & Shafer, 2001a). In general, it is considered that recreation specialization is a multi-dimensional concept consisting of affective, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions. Of the many previous studies related to recreation specialization, there are few that measure all three dimensions (McFarlane, 2004). For instance, Bryan (1977 assessed attitude and behavior; McIntyre (1989) and Shafer and Hammit (1995) utilized only the affective dimension; Ditton et al. (1992) and Donnelly et al. (1986) used only the behavioral indicators; and many researchers measured both behavioral and attitudinal factors (e.g., Bricker & Kerstetter, 2000; Kuentzel & McDonald, 1992; Virden & Schreyer, 1988). In the present study, all three dimensions were measured, but the behavioral dimension was excluded due to the low factor loading value extracted from the CFA. However, the use of the affective and cognitive dimensions, which could be regarded as important components of recreation specialization, was still enough to find meaningful results.

Regarding the role of motivation and negotiation, in the independence model constraint, negotiation and motivation had significant effects on recreation specialization while having significant correlations with one another. Specifically, negotiation and motivation had positive correlations with each other, whereas these had negative correlations with constraint. These correlations had a similar pattern with effects on recreation specialization. In other words, negotiation and motivation promoted recreation specialization, while these reduced constraint. Therefore, negotiation (

In the constraint-effects-mitigation model, this model showed that constraint and motivation, which had negative correlations with each other, had significant effects on negotiation and recreation specialization. Constraint had negative effects on negotiation and recreation specialization, whereas it had a positive effect on motivation. Particularly, this model showed the mechanism by which negotiation could be reduced by constraint, but increased by motivation. This model is not consistent with the results of Hubbard and Mannell’s (2001 study, but consistent with Jackson ea al.’s (1993) proposition. Their study demonstrated that constraint had a positive effect on negotiation, while in the present study constraint had a negative effect. In general, when recreationists face leisure constraints, they are likely to make some effort to surmount these constraints. In the case that it is impossible to overcome the constraints, however, these constraints could have recreationists lose the will for negotiation.

In the perceived-constraint-reduction model, not only did motivation directly facilitate recreation specialization but it also did so indirectly through negotiation efforts and reduction of constraints. The flow structure of this model is different from that of Hubbard and Mannell’s(2001) model, showing the structure that negotiation facilitated by motivation had a positive effect on constraint. In spite of the negotiation theory (Jackson et al., 1993) that utilizing the leisure constraint negotiation strategies reduces leisure constraints, the results of Hubbard and Mannell’s (2001) study did not support the theory because their model indicated that leisure constraints are increased as the efforts of negotiation are increased. The indirect effects of motivation on recreation specialization through negotiation and constraint (.57 × -.29 × -.17 = .03) and negotiation (.57 × .52 = .29) in the present study suggested that negotiation reduces the effect of constraint, finally resulting in the positive indirect effect of motivation on recreation specialization.

In sum, the motivation and negotiation variables are useful in predicting recreation specialization in the constraint-effects-mitigation model and the perceived-constraint-reduction model. Specifically, motivation and negotiation appear to contribute to recreation specialization. Simultaneously, motivation and negotiation appear to play the roles of reducing and mitigating constraints for progressing to recreation specialization as well. This means that motivation and efforts to negotiate constraints, rather than leisure constraints alone, are important determinants of recreation specialization. Finally, With two better models(constraint-effects-mitigation and perceived-constraint-reduction models), the constraint-effects-mitigation model did not support the trigger role of leisure constraint on negotiation (Jackson et al., 1993) with inconsistence of Hubbard and Mannel’s (2001) study and the perceived-constraint-reduction model did support the reduction role of negotiation on leisure constraint (Jackson et al., 1993) with inconsistence of Hubbard and Mannel’s (2001) study.

It is recommended that future studies on the leisure constraint negotiation process be conducted as follows: First, the levels of recreation involvement should be tested in a variety of leisure activity types, such as passive and active activities, sedentary and physically active activities, and extreme activities. It is anticipated that the levels of leisure constraints, motivation, negotiation, and specialization could be different according to the types of leisure activity. For instance, physical recreation activities as active activities could have more and various constraints than spectator sports and appreciation of music as passive activities. Second, the process of recreation specialization should be investigated in relation to demographic characteristics and socio-economic status since these factors have significant influences on participation in leisure and recreational activities. Research on the degree of recreation involvement and the process of constraint negotiation based on these factors would be helpful to reach a better understanding of the nature of recreation specialization. Similarly, while there is nothing to suggest that the Korean sample used in the current study would be different from samples from other countries, the possibility of cultural variations should continue to be examined.

Finally, the scale of recreation specialization should be developed. As previously mentioned, the present study excluded the behavioral dimension to measure recreation specialization due to its low factor loading values. Therefore, recreation specialization in the present study does not adequately reflect the behavioral dimension even though these are important indicators of the level of participation in leisure activities. Consequently, future studies need to explore the ways that improve the construct validity of the behavioral dimension.