The literature on the international taxation of firms is largely dominated by studies of how taxes affect the location and quantity of foreign direct investment (FDI). It is perhaps unsurprising that the empirical literature has broadly identified a negative relationship between the level of corporate taxation in national jurisdictions and the corresponding level of inward FDI (see Hines, 1999, for an overview and De Mooji & Ederveen, 2003; Devereux & Maffini, 2007, for surveys). The theoretical literature (see Krogstrup, 2002; Haufler, 2001;Wilson, 1999) suggests that disparities in corporation tax between competing host locations can be sustained via asymmetries between countries (Ottaviano & vanYpersele, 2005; Haufler & Wooton, 1999), although the international mobility of firms serves to put pressure on tax-setting authorities to keep taxes low (Janeba, 1998, 2000; Bond & Samuelson, 1989). In this connection, it is worth noting that the literature has most commonly focussed upon one type of response to an unattractively high tax in one location – the relocation of production to alternative host countries. It has, therefore, largely overlooked the potential for such taxes to affect the mode of engagement in foreign markets, e.g. export versus local production through FDI.

Furthermore, the literature to date has largely ignored how corporate tax rates might affect the composition of FDI. The reason being is that the literature has commonly assumed away heterogeneity across firms. Indeed, there is a common assumption of monopoly, with an accompanying focus upon the effect of the rate of tax on local tax revenues (and employment). However, one might expect the effect of an FDI on local tax revenues, employment and welfare to substantially vary depending upon the attributes of the firmthat undertakes the FDI. For example, thewelfare dividend for a host from attracting inward FDIwould be expected to vary across industries, e.g. firms in high technology industries might offer a relatively great benefit in the forms of high-value-adding production processes, highly-skilled jobs for locals and technology spillovers. It is not only differences across industries, but also differences across firms within each industry, that might affect the outcomes associated with inward FDI.

It is upon such intra-industry variation that this paper will focus.We will highlight the potential for corporate tax rates set within a national jurisdiction to influence the scale and composition of the inward FDI attracted to that country. More specifically, given that firms in an industry differ in cost efficiency, we investigate the effect of a local corporate tax on whether a country attracts FDI by the most or least cost-efficient firms. Any such effect is in addition to the potential influence of corporate tax rates on the scale of FDI, i.e. the associated reduction in the net profitability of host country operations affects both the absolute attractiveness of FDI and its attractiveness relative to exporting. In the presence of such scale and composition effects, one would expect both of these to affect tax-setting, i.e. policymakers will seek to both avoid an excessive deterrence of inward FDI and ensure that the inward FDI attracted is undertaken by firms that are more, rather than less, efficient, and which are therefore better-placed to set lower prices for host consumers and generate taxable profits. In this connection, the author is aware of only one paper that examines the affect of corporate tax rate on the composition of FDI. However, in stark contrast to the oligopolistic setting of the model presented here, Becker

Despite the policy focus of this work, our model is also related to recent developments in trade theory, which has sought to incorporate heterogeneity in individual firm characteristics. Motivated by recent empirical findings that acknowledge a strong correlation between firm-productivity and export status (Bernard & Jensen, 2004; Girma

Thus, this paper makes three main contributions to the extant literature. First, it extends the relevant tax-related literature by presenting a novel analysis of the under-explored potential for corporate tax to affect not only the scale but also the composition of FDI in respect of characteristics that can affect the host-country welfare implications of the FDI. Second, as we focus specifically on the composition of FDI regarding the cost-efficiency of the firm or firms that are attracted to the host location, a further novelty of our analysis is that the potential for only the relatively cost-inefficient to undertake FDI in equilibrium, which is an artefact of oligopolistic strategic interaction between firms, is demonstrated alongside the potential for host-country tax-setting to induce or avoid such an outcome.

Third, we model the choice for firms of whether to export or undertake FDI. In the relevant tax-related literatures, the choice of which location to sink any foreign direct investment is typically modelled but the choice of foreign production in preference to exporting is presumed. In the oligopolistic setting, such as is modelled here, there is potential for the choice between exporting and FDI to be used strategically by firms to shift the competitive balance of the market outcome to their own advantage relative to rival firms. Thus, the inclusion in our model of this choice as a constituent part of the internationalisation process may substantively affect the context for policymaking, and specifically the effect of tax-setting on FDI in equilibrium.

The following section outlines the set-up of the model. Section 3 presents the feasible range of subgame-perfect equilibria for a simplified game with homogeneous firms in the absence of taxation. In Section 4, firm heterogeneity is introduced while in Section 5 we add an exogenous host country corporate profit tax. Section 5.1 outlines the welfare implications of this tax, while Section 6 explores endogenous tax-setting prior to some concluding comments in Section 7.

1It is also worth noting that firm asymmetry under conditions of oligopoly has been addressed in the distinct but related strategic trade policy literature, see Collie (1993); Van-Long and Soubeyran (1997), and Leahy and Montagna (2001).

There are two firms, Firm 1 and Firm 2 , and two countries, a source country and a host country. Both firms are potentially multinational and each is located in the source country. Set-up costs of production in the source country are treated as sunk prior to the commencement of the game. Thus, the firms have already established domestic production plants when the opportunity to serve an overseas market arises. This foreign market, which resides in the host country, has a demand for the good that is and will not be met by indigenous industry. However, there exists the following tension: if a firm wishes to exploit advantages associated with the concentration of production at home it must incur the necessary transport costs associated with transferring the good internationally from the site of production to the site of consumption; alternatively, if a firm wishes to exploit proximity advantages associated with locating production within the host country, it must absorb the additional fixed costs of establishing a plant there. Decision-making is represented in a two-stage game. First, firms must simultaneously decide whether or not to enter the foreign market and, if so, whether to serve the market via exports or via direct investment. In the second stage of the game, firms simultaneously choose outputs dedicated to the foreign market.

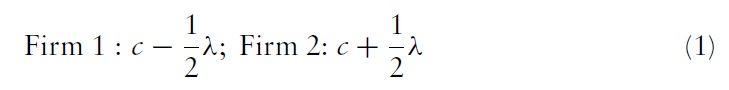

Each firm produces the good at a constant marginal cost determined by the parameters

For each unit of the good exported, a firm must pay

Given the normalisations of both the intercept and slope of the demand curve, transport costs can be interpreted as measured with respect to market size.

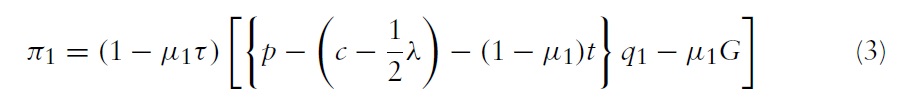

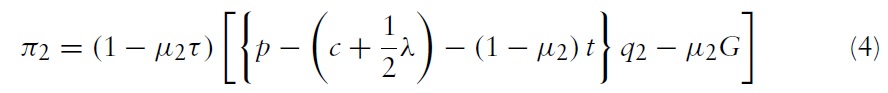

The game is solved by backward induction, i.e. we first must obtain equilibrium outputs, and hence prices and profits, for each firm under every possible combination of the firms’ first-stage choices. The solution concept is sub-game perfect Nash equilibrium, which requires that each firm makes an optimal choice given it has correct beliefs regarding its opponents optimal choice.This procedure can be easily illustrated using equation (1) and by considering the following profit expressions where

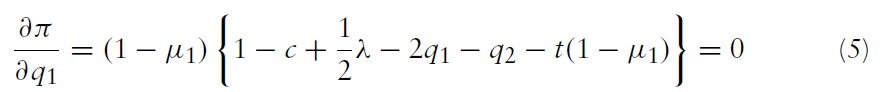

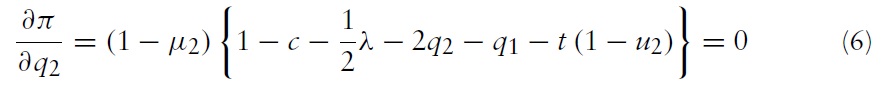

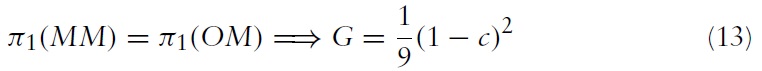

Assuming that firms maximise profits, the first-order conditions are:

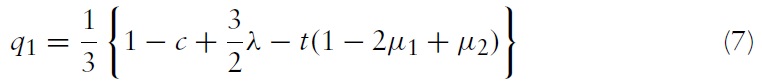

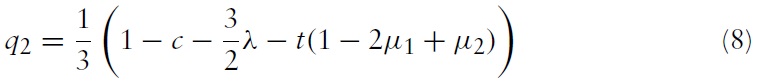

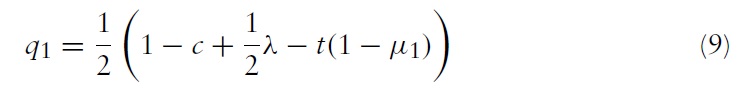

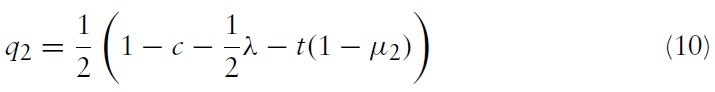

Manipulation of equations (5) and (6) yields the equilibrium values for outputs given duopoly in the host country market

Equations (2), (3) (4), (7) and (8) allow us to solve for equilibrium prices and profits. If only one firmserves the host country market in equilibrium, then either Firm 1 or Firm 2 will set output as a monopolist, as follows:

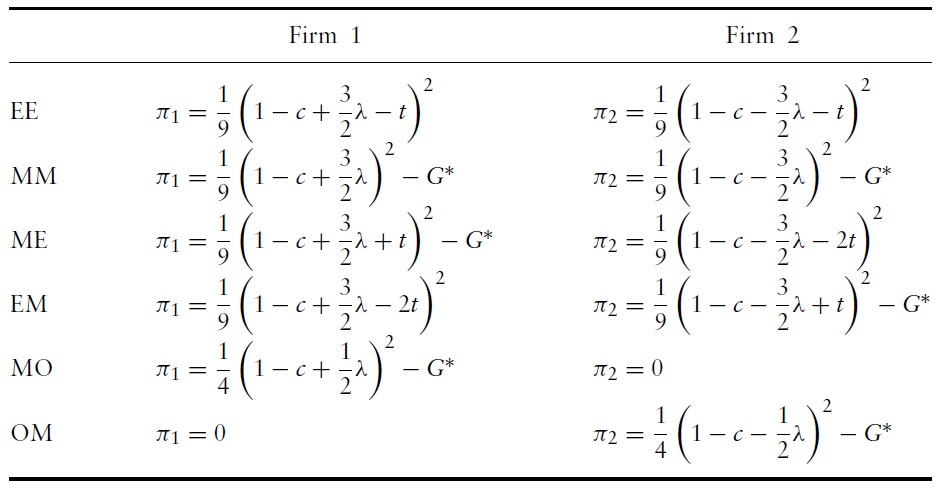

Equilibrium Profit

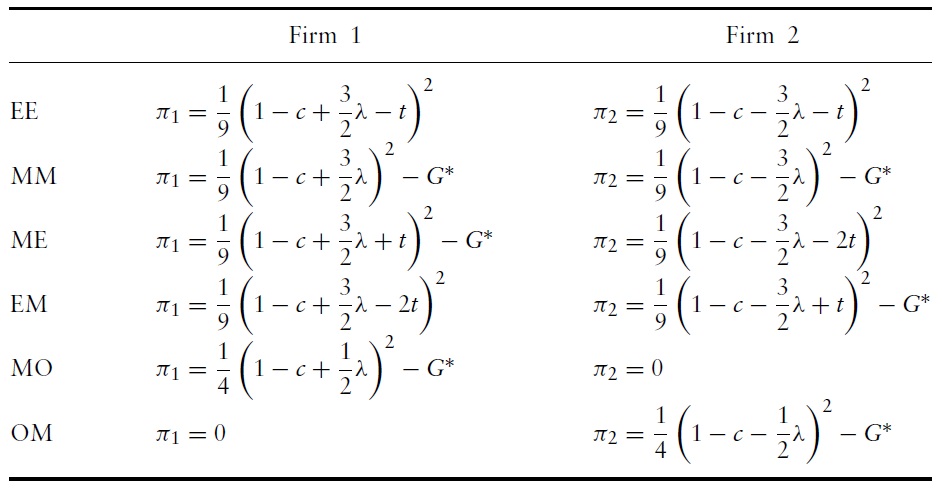

Profits for each firm under each of the possible combinations of internationalisation strategy are summarised in Table 1. On notation, the equilibrium outcomes are represented as follows: MM – duopoly in the host country market with both firms serving the market through local production; EE – exporting duopoly; ME(EM) – Firm 1(2) chooses to be multinational while Firm 2(1) is an exporter; MO(OM) – two-plant monopoly. Simply put, the exporting strategy is denoted by ‘E’ and ‘M’ denotes the multinational strategy, while the strategic choice to not serve the foreign market is denoted by ‘O’.

Each profit expression contains an operating profit component, and those associated with multinational operation contain an additional fixed cost element. While the parameters

3. Results for an Initial Base Case: Identical Firms and Absent Corporate Tax

We initially present results with neither a cost differential between the firms (i.e.

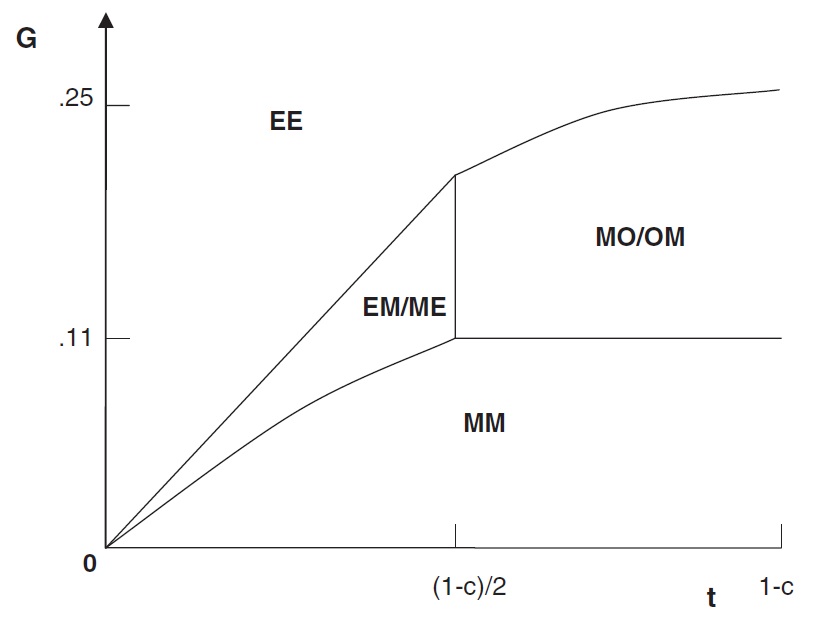

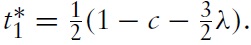

Given firm symmetry, Figure 1 describes, for the set of feasible parameter combinations, the market structures that prevail in equilibrium.2 It is generated by considering the various profit boundaries in

For

The boundary between the regions ME(EM) and EE gives the combinations of

For

Below the boundary, both firms choose to be multinational, whereas above the boundary fixed costs are at a level such that the market can support at most, one multinational firm. The boundary that divides the MO(OM) and EE outcomes lies at combinations of

Overall, Figure 1 displays the following expectable pattern: increases in t tend to bring shifts towards greater FDI; whereas increases in G tend to bring shifts towards exporting. Consistent with this, dualmulti-plant production(MM)arises when fixed costs are small relative to transport costs. For intermediate values of fixed costs and transport costs, the asymmetric equilibrium ME or EM arises; when transport costs are large relative to fixed costs, there is a multinational monopolist in equilibrium. These outcomes highlight that across a range of parameterisations, there is strategic interdependence between the firms in respect of their FDI decisions. Specifically, each firm’s best response is to choose FDI only if the rival firm does not choose FDI, and this results in multiple FDI equilibria, i.e. ME(EM) and MO(OM). Thus, FDI strategy is determined by both cost and strategic considerations.

2In Figure 1, an upper bound on t is imposed, which marks the zero output condition for an exporting duopoly. 3This represents the zero output condition for the outcomes ME(EM). 4The emergence of multiple equilibria is a direct consequence of strategic interaction. In cases of multiple equilibria, the determination of which outcome will emerge as an equilibrium outcome, i.e. in this instance either EM or ME, is, without further assumptions, beyond the scope of this model. However, in terms of equilibria selection, multiplicity of equilibria poses important policy implications. This issue will be addressed further in Section 5. 5The upper bound on MO(OM) region in Figure 1 is defined such that the optimal response to exporting by one firmis for the other firmto undertake FDI, rendering the exporter loss-making and causing it to prefer not to serve the foreign market (MO(OM)). Above the boundary, the optimal response to exporting by one firm is for the other firm to also export (EE) – a profitable outcome for both firms.

4. Results: Firm Heterogeneity in Cost-efficiency

We will now (and hereafter) assume that

and is lower for the relatively cost-inefficient firm, at

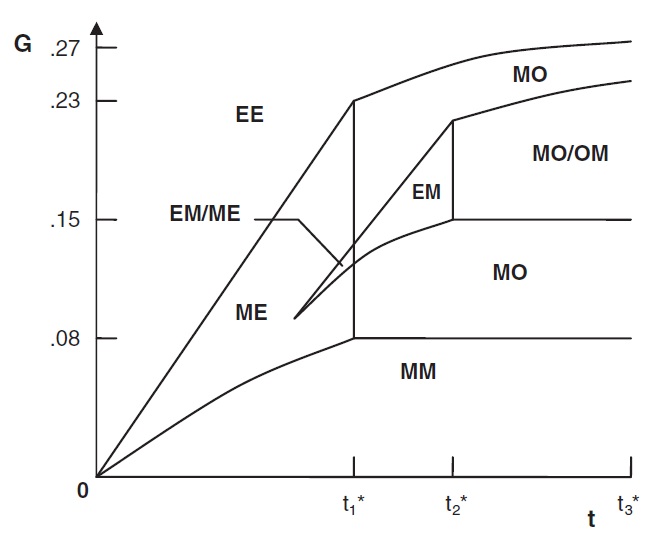

6 Moreover, as a result of the such changes, asymmetric equilibrium configurations not seen in the symmetric case emerge – MO(EM) and MO – as presented in Figure 2.

Overall, in comparison with Figure 1, there is (i) a contraction ofmultinational duopoly (MM) and exporting duopoly (EE), which exhibit strategic symmetry; (ii) an expansion of multinational monopoly for the cost-efficient firm; and (iii) a contraction of potential multinational monopoly for the cost-inefficient firm. The results follow from the tendencies for cost-asymmetry to promote strategic asymmetry and for lower (higher) variable production costs to boost (reduce) a firm’s incentives to serve a market (with or without competition from a rival) and incur the fixed cost of FDI. Thus, the introduction of firm heterogeneity to our duopoly model makes FDI by the cost-(in)efficient firm more (less) prevalent across feasible parameterisations.

However, in this connection it is worth noting that, in those circumstances where only one firm will undertake FDI, cost-efficient Firm 1 is not sure to be the multinational – rather, the EM and OM outcomes remain possible equilibrium outcomes. Despite the cost advantage for Firm 1, it may be that, were Firm 2 to undertake FDI, Firm 1’s best response would be to not follow suit. This is because Firm 2 as a multinational would avoid the increase in variable costs that would be suffered as an exporter (i.e. they avoid

6Note that here we consider a feasible range of equilibria with an upper bound of which marks the upper limit for the outcome EE in equilibrium.

5. Results: Firm Heterogeneity and an Exogenous Host Country Corporate Tax

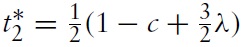

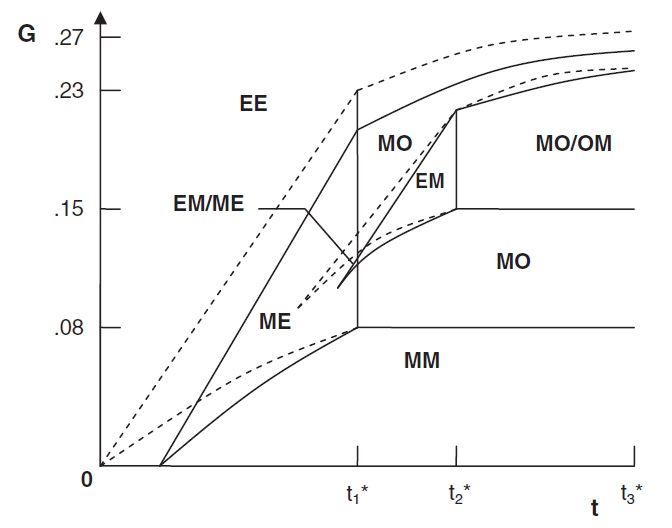

This section analyses the extent to which the imposition of a pure profit tax inhibits multinational activity. That is, we introduce an exogenous tax (

It is evident from Figure 3 that regions corresponding to multinational activity have contracted in size. As one would expect, the tax on multinationals’ profit causes FDI to be a less attractive means of serving the foreign market. For example, the multinational duopoly equilibrium emerges only at higher transport cost levels and all regions accommodating the equilibria ME, EM, MO, OM also contract. Thus, it serves to inhibitmultinational behaviour and encourages armslength penetration of the market, with an expansion of the exporting duopoly and exporting monopoly regions. In this connection, it is worth highlighting one particular shift in equilibrium outcome: from MM to ME. Thus, if, as a result of the corporate tax, only one firm changes its configuration, it will be the costinefficient firm that will be driven out of local production in the host country. This is because the larger ceteris paribus profit margin of the cost-efficient firm boosts that firm’s capability to earn operating profits in excess of the fixed cost of FDI, and thus the cost-efficient firm is less easily deterred from FDI than is its rival.

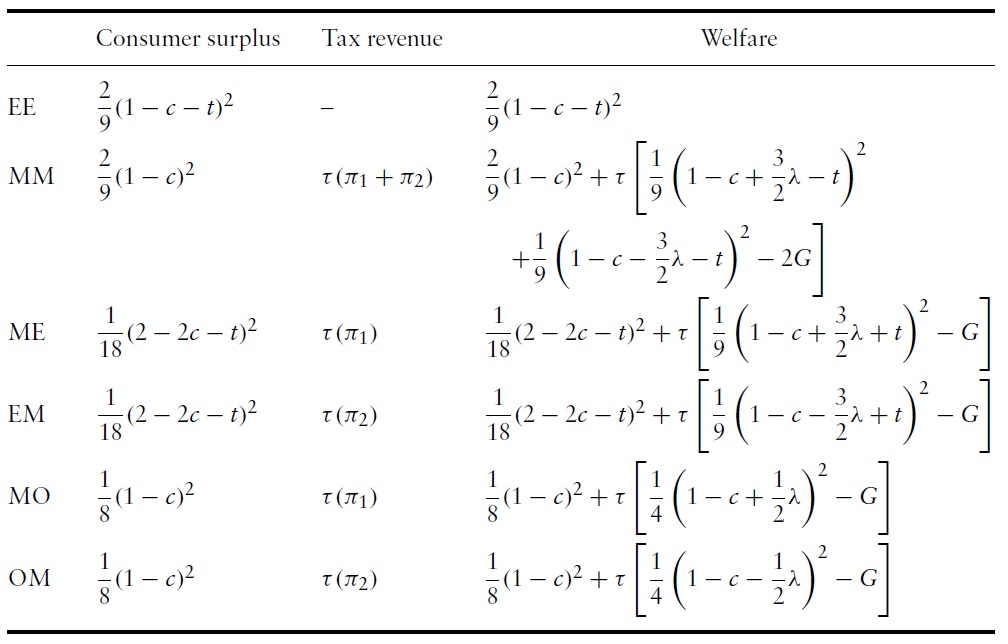

5.1 Welfare Implications of the Exogenous Tax

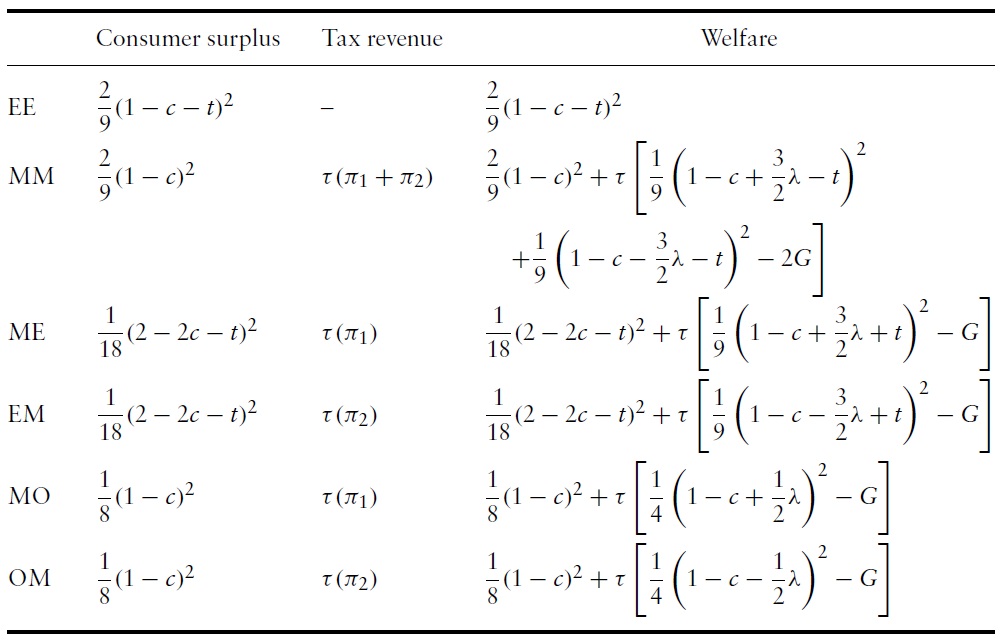

Before moving on to endogenous tax-setting, we will next consider the welfare effects of the tax, including those from the tax-induced shifts in equilibrium plant configuration. An increase in the tax parameter has two distinct effects. First, it directly increases tax revenue for the host government. Second, it can deter FDI by both firms, although this effect is stronger for the cost-inefficient firm. Indeed, it is not only thatMMmight be replaced byMEas a result of a change in tax, but also that EM might switch to ME, or that EM orOMmight switch toMO. In all these additional cases, FDI by the inefficient firm is replaced by FDI from the efficient firm. Such shifts have positive implications forwelfare owing to the cost-efficiency of Firm 1, tending to both depress prices for host-country consumers and boost the taxable profits within the jurisdiction.Welfare analysis here is complicated by the prevalence ofmultiple equilibria, and for completenesswe will,wheremultiple equilibria are possible, consider all of these in our analysis. In keeping with the assumption that no indigenous production takes place in the foreign country, we define foreign welfare as the sum of consumer surplus plus any tax revenue earned from Firm 1 and/or Firm 2. Therefore, in instances where no change in plant configuration is observed, increases in tax rate are welfare improving for the host country. Table 2 presents welfare expressions for the foreign country for the range of plant configurations.

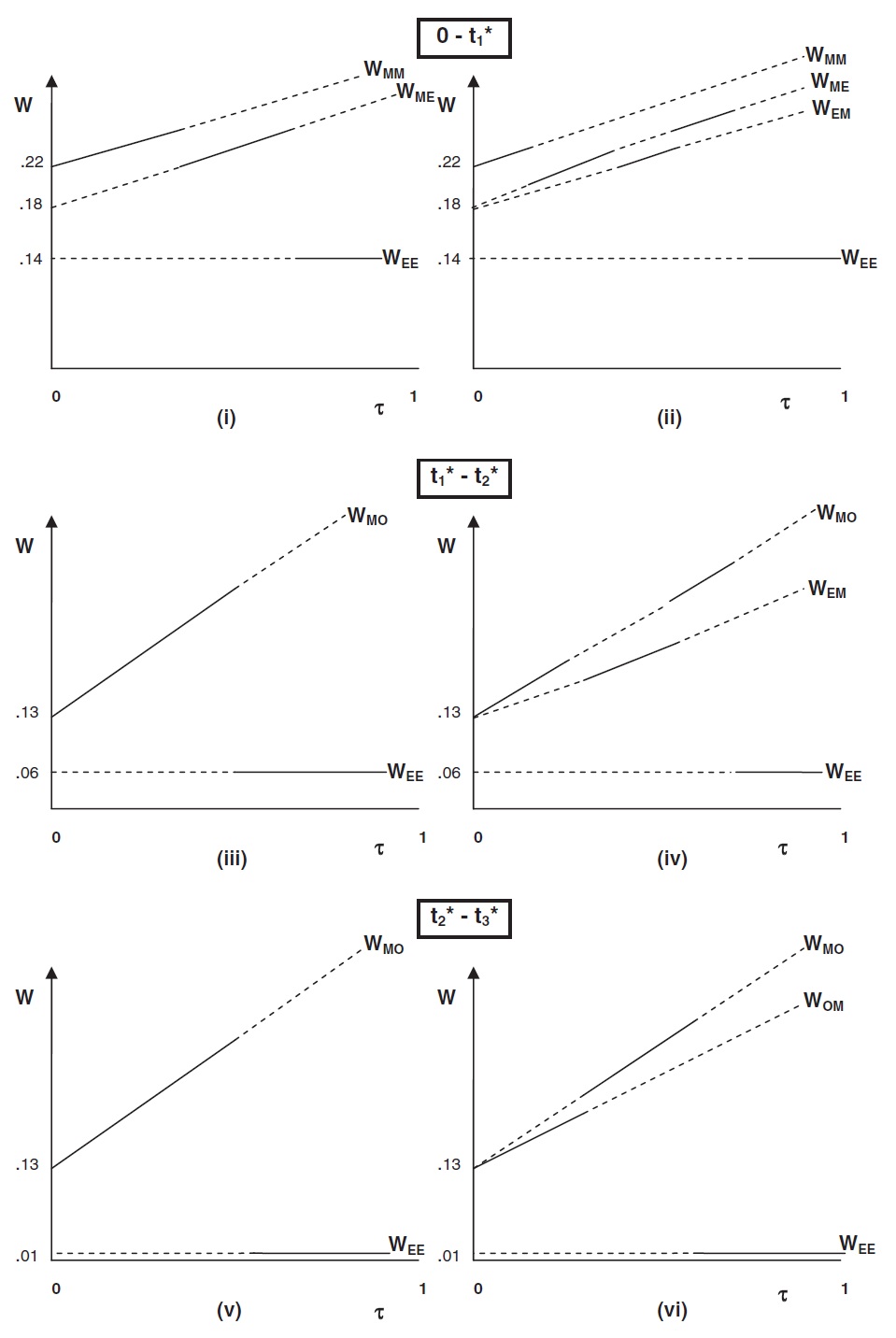

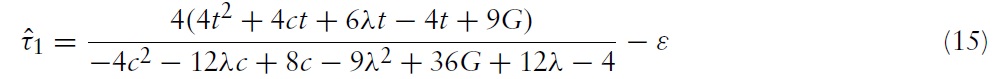

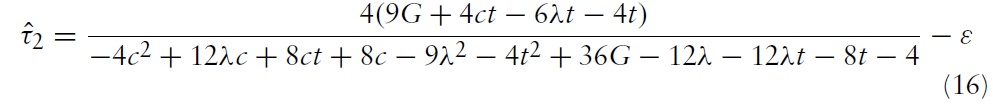

To examine thewelfare effects of such tax-induced shifts in plant configurations we proceed by dividing the space of Figure 3 into three main sections according to the three transport cost thresholds (

Welfare

Figures 4(iii) and (iv) repeats the exercise for transport cost values between t∗ 1 and t∗ 2 , where Figure 4(iii) illustrates the possible sequence of plant configuration changes assuming MO rather than EM emerges in the MO(EM) region and Figure 4(iv) illustrates the possible sequence of plant configuration changes assuming EM is selected from the multiple equilibria. In the former figure, gradual increases in taxation are shown to shift plant configuration from MO to EE with negative implications for welfare. The latter figure depicts a broader range of shifts in plant configuration from MO to EM, from EM to MO and from MO to EE, where the middle of these three shifts from an increase in tax rate is associated with an improvement in host country welfare. Finally, Figures 4(v) and 4(vi) illustrate for transport cost values between (

Overall, Figure 4 demonstrates that marginal increases in taxation can induce large changes in host country welfare. In addition, shifts in plant configuration induced by an increase in the tax rate bring about welfare losses for the host country in many cases, but can instead bring a welfare dividend for that country – this is the case where a tax rate increase induces FDI by the cost-efficient firm.

7Modelling taxation in this way is analogous to assuming that fixed costs are fully tax deductible. It is also worth noting that, as the policy instrument modelled is a profit tax, rather than output tax or some other region-specific revenue-raising policy that exerts some direct effect on output-setting, it affects FDI decisions in a manner akin to a lump-sum transfer. Therefore, our results regarding a corporate profit tax may, at least in part, straightforwardly generalise to host-country FDI policies that subsidise a foreign firm towards the fixed cost of FDI, e.g. the public provision of production infrastructure through the strategic and targeted building of industrial parks. 8Note that for the highest levels of taxation, regions hosting some equilibria outcomes may disappear altogether, with taxation thus having a more exaggerated impact on the chosen production regime. 9As was found in Hostmann and Markusen (1992) and Motta and Norman (1996), even small changes in certain parameters can induce large changes in welfare functions.

6. Results: Firm Heterogeneity and an Endogenous Host Country Corporate Tax

In this section,we will extend the model to incorporate endogenous tax setting by the host government, which seeks to maximise host country welfare as previously defined. In order to ensure that FDI decisions are taken in the context of a given policy environment, we assume that the host government moves first in a bid to pre-empt firm behaviour. The move-order is as follows.

Stage 1: Host government sets the local corporate tax rate

Stage 2: Each firmchooses whether to serve the foreign market, and if so whether to export or undertake FDI.

Stage 3: Each firm sets its foreign-dedicated output.

Optimal tax-settingmust take into account not only direct effects on tax revenues but also the potential for the tax rate to affect the firms’ internationalisation strategies. The effects on welfare due to the latter considerations are described in Figure 4, which shows the potential for tax-setting to be optimally employed to ensure that it is the cost-efficient firm, rather than cost-inefficient firm, that locates within the jurisdiction – i.e. that ME prevails rather than EM or thatMO prevails rather than OM.

To solve for optimal tax-setting, we must consider all potential equilibrium plant configurations and all possible shifts in FDI strategy that can be induced by a change in tax rate. First, for every parameterisation that, for all positive tax rates, brings exporting duopoly (EE), neither firm pays the tax, tax revenues are zero and both corporate strategy and welfare are independent of the tax rate. In that case, optimal tax-setting provides for all

While there are five possible plant configurations that include FDI – MM, ME, EM,MOandOM– only three of these offer the prospect of the highest achievable level ofwelfare for the host country –MM,MEandMO.The exclusion ofEMand OM is driven by the foregone host-country welfare associated with the relatively cost-inefficient firm rather than the cost-efficient firm serving the local market (as reflected in a deleterious impact on consumer surplus) and setting-up local operations (as reflected in a deleterious impact on tax revenues).

The potential for the MM or ME to offer the highest achievable host-country welfare is illustrated in Figure 4(i), which is drawn to reflect that it is ambiguous whether MM or ME offers a higher maximum level of welfare. This is because

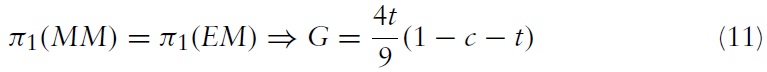

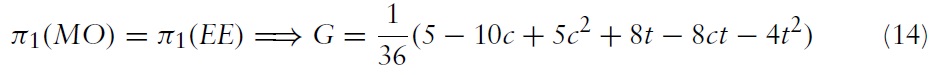

MM provides for two taxable profits and a relatively high level of consumer surplus but occurs only at a relatively low tax rate, whereas ME provides for only one taxable profit and a lower level of consumer surplus but permits a higher tax rate and so greater tax revenues to be collected from Firm 1. For some parameterisations, MM offers the highest achievable welfare and the optimal tax is the highest that does not deter Firm 2 from undertaking FDI given that Firm 1 is multinational – this is

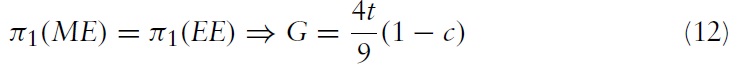

For some parameterisations, ME offers the highest achievable welfare and the optimal tax is the highest that does not deter Firm 1 from undertaking FDI given that Firm 2 exports – this is

Indeed, the potential for ME to offer the highest achievable level of host-country welfare is also illustrated in Figure 4(ii). In that scenario, the optimal tax is again the highest that does not deter Firm 1 from undertaking FDI given that Firm 2 exports, i.e.

once again.

The potential for the optimal tax rate to be thatwhich secures theMOoutcome is illustrated in Figures 4(iii), 4(iv), 4(v) and 4(vi). In that case, the imperative for the host-country policymaker is to set the highest tax rate that does not deter Firm 1 from undertaking FDI when such investment secures a monopoly position in the foreign market (MO), given that were Firm 1 to instead export, Firm 2 would follow suit (EE) – this is

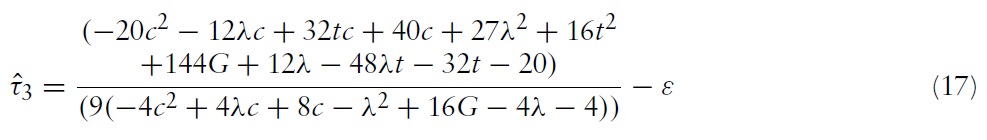

The three optimal tax rates described above

and

are as follows (where, in each case, ε denotes some small amount and reflects the imperative to suitably incentivise the required pattern of FDI):

The analysis suggests that a host-country corporate profit tax can be optimally used to manipulate not only the scale but also the composition of FDI. That is, while taxation discourages FDI by both firms ceteris paribus, it can also be set to ensure that FDI by the cost-efficient firm is more prevalent in equilibrium. The model illustrates a role for policymakers that derives from a tendency for the strategic interdependence found in oligopoly to precipitate the emergence of FDI by a relatively cost-inefficient firm that rules out any such investment by a relatively cost-efficient rival. Given the unattractive effects on host-country welfare associated with a pattern of FDI that favours such inefficiency, there is an imperative for the tax rate to be set to promote FDI by the cost-efficient firm where it is beneficial to do so. Simply put, the execution of such a policy implies a tax rate that is sufficiently high to deter FDI by the cost-inefficient firm, but not so high as to deter FDI by the cost-efficient firm.

We present a duopoly model with heterogeneous firms that vary in cost-efficiency, each ofwhich can choose to serve a foreign market by either exporting or local production. We do so to analyse the effects of a host-country corporate profit tax on both the scale and composition of FDI, and find that strategic interaction between oligopolistic firms provides for a pattern of FDI that favours cost-inefficiency to the detriment of host-country welfare; and the host-country tax rate can be optimally used to avoid such patterns of FDI and instead promote direct investment by a relatively cost-efficient firm.

Although simple and abstract, the model provides for a broad variety of equilibria, encompassing strategic symmetry and asymmetry among firms, and a wealth of strategic interactions, both among the firms and between a tax-setting policymaker and the firms. Regarding corporate internationalisation strategy, the choices observed here echo results found by Helpman

In future research, the model presented might be usefully extended in a number of ways. For example, as the model fixes the total number of firms at the theoretically elegant but empirically uncommon duopoly, endogenising the creation of firms, and the accommodation of a broader range of market structures (to include oligopolies of more than two firms) would be potentially useful next steps. In addition, while tax-setting in the host-country jurisdiction is modelled and discussed, we do not accommodate FDI policy by the source-country government. While such analyses lies beyond the scope of this paper, it may be that a source country policymaker would, guided by an imperative to maximise repatriated profit net of subsidy payments, set a corporate subsidy to promote certain plant configurations in equilibrium. Specifically, given that the cost-efficient firm generates greater profits ceteris paribus, the source-country government may, if international agreements permit, offer to the most cost-efficient firm(s) a subsidy that offsets the fixed cost of FDI. Such a policy would be reminiscent of the practice of ‘picking winners’ that was commonly observed at the time when the identification and support of national champions exerted a strong influence on the industrial policies of numerous countries.