The effect of labor unions on firm profitability is an important subject of inquiry in the study of industrial relations. The broad view emerging from existing studies is that labor unions (henceforth unions) generally lower firm profitability, but whether they actually do so depends on the circumstances. The circumstances often mentioned are whether firms have a competitive or a non-competitive position in the product market and whether firms have cooperative industrial relations (Freeman and Medoff, 1984, Chapter 12; Metcalf, 2003; Doucouliagos and Laroche, 2009). However, there are other factors that are as important as these circumstances.

Most of all, the effect of unions on profitability may be affected by the political environment. The political environment determines the legal and other institutional settings for unions. It may also affect the actual behavior of the state, which may have discretionary power in putting legal and institutional settings into practice. In the United States, for example, before the New Deal, the federal government was an ally of employers seeking to suppress unions, but the New Deal ushered in progressive politics in the 1930s, providing a favorable environment for unions (Krugman, 2009, pp. 50–53). On the other hand, the ascendancy of the conservative political environment since the 1980s should have provided an unfavorable environment for unions. The situation is similar in the UK. This change in the political environment may, at least partially, account for the empirical findings showing that the negative effects of unions on profitability and other financial performance of firms were weakened during the 1980s and 1990s in the US and the UK (DiNard and Lee, 2004; Menezes-Filho, 1997). In other developed countries, the changes in political environment is less clear, and no empirical evidence is available about the weakening of the union effect on profitability or other financial performance of firms. However, the decline of unions from the 1980s and its possible bottoming out in the 2000s is attributed at least partially to political environments (Bryson

The relationship between the political environment and the effects of unions on firm profitability, or the union bargaining power underlying it, may be more pronounced in developing countries. In developed countries, the political system is always a democracy, regardless of whether the prevailing atmosphere is progressive or conservative. In developing countries, the political system may be authoritarian or democratic. One may expect that, as a rule, democracy will be more favorable to unions.However, the actual relationship is often more complex. In many developing countries in Latin America and Africa, despite the remarkable case of Chile, an authoritarian state may co-opt unions and make them partners in the authoritarian rule. Meanwhile, in the high-growth economies of East Asia, a repressive political environment for unions was an important feature of their political system in the early phases of their economic development (Deyo, 1989; Nelson, 1991).

We also need a broader perspective when dealing with the economic environment. When industrial relations literature has traditionally focused on the conditions in the product market, the implicit assumption is that a competitive product market works as a formof ‘discipline’ upon unions. If the firmis shielded from competition, unions can erode profitability; if it is exposed to competition, they cannot do so. However, in terms of imposing discipline, the financial market condition may be as important as (or more important than) the product market condition.

One such condition is the degree of shareholder protection.When shareholder protection is strong, with shareholders having a strong voice in management or with hostile mergers and acquisitions (M&As) being activated (corporate raiders are the natural ally of minority shareholders), firms are under pressure to raise ‘shareholder value’ by raising profitability. Under such circumstances, unions will find it difficult to profit at the expense of shareholders. On the other hand, when shareholder protection is weak, the pressure upon unions is weak and possibility for such gains is high (Pagano and Volpin, 2005; Atanassov and Kim, 2009). Thus, for example, the M&As of corporations in the 1980s partly reflected shareholders recouping of the value of ‘rents’ held by unionized workers (Becker, 1995).

Another such condition is the discipline imposed by creditors. Creditors can impose the threat of bankruptcy when the leverage ratio is high, which makes it easier to discipline the behavior of workers (Bronars

Existing studies have not dealt with these problems adequately. No empirical study has analyzed explicitly the difference in the union effect on profitability under different political environments. Naturally, there is no study about the difference in the union effect on profitability under authoritarian and political regimes in developing countries. There is also a relative shortage of studies about the union effect on profitability under different financial market conditions.

We will try to fill this gap in a rudimentary way using the firm data of South Korea (henceforth Korea). Korea provides good empirical grounds for testing the union effect on profitability under different political and economic environments. Korea underwent a dramatic change in its political environment in the process of economic development. The country moved from an authoritarian military regime to a democratic polity in 1987. The economic environment also changed drastically, as the country experienced a radical change in its financial market conditions after the foreign exchange crisis in 1997.

In the rest of this paper, we first describe the Korean situation in terms of the political and economic environments for unions and their changes over time.We divide the periods considering those changes and discuss the possible union effect on profitability for each period. We then proceed to the empirical analysis and present its results.

1The decline of unions may also have bottomed out in the UK from 1997 with the incumbency of the Labour government (Blanden et al., 2006).

2. Political and Economic Environments for Unions in Korea

The political environment for unions has changed drastically over the years in Korea, with a major break occurring in 1987.2

Korea had an unfavorable political environment for unionswhen high economic growth began in the 1960s. The anti-communist ideology evident in Korean society since theKoreanWar (1950–53)was frequently used by the state and employers as an ideological weapon to repress independent unions. The repression continued in the 1970s and culminated during the military dictatorship of the Fifth Republic (1980–87), which will be the first period of empirical analysis in this paper. During this period, labor laws were most unfavorable to unions. An enterprise union system was forcefully imposed on the premise that it would reduce union bargaining power. Multiple unions, both at the firm and national (trade union federation) levels, were prohibited with the belief that prohibition would enable employers to control unions more easily. Political activity by unions was prohibited. Labor laws also prohibited union shops, the involvement of third parties – including trade union federations – in workplace-industrial relations, as well as strike activity outside the workplace. A long cooling-off period for strikes was imposed.

As important as (or even more important than) laws was the behavior of the executive branch of the state (henceforth the ‘government’), which tended to dominate the legislative and judiciary branches under the authoritarian regime. It could exert wide-ranging discretionary power through enforcement ordinances, which included the rights to order the dissolution of particular unions, limit the qualifications of union officers, demand the re-election of particular union officers, and inspect the daily operations of unions. There were also unofficial and hidden interventions that included mobilizing the police and sometimes the (ubiquitous) secret police.The government used this method because many government officials perceived industrial relations from an anti-subversion perspective.

While severely repressing independent union activities, the state gave relatively strong protection to individual workers. Labor laws made it impossible to fire workers on the grounds of the poor financial performance of the firm. They also defined the working hours rigidly. The laws decreed priority of the payment of wage claims to other liabilities when firms went bankrupt. However, whether the laws were obeyed was another matter. Employers generally ignored the laws and the government was not interested in enforcing them.

The onset of democratization in June of 1987 critically changed the political environment for unions.At that time, independent union activity became possible for the first time in Korean history. Labor laws were revised in 1987, as the steep rise in strikes made the existing laws invalid. The laws ceased to impose enterprise unions and lifted the prohibition on union shops. The cooling-off period for strikes was shortened. The revisions repealed the discretionary power of the government, including the right to order the dissolution of particular unions, limit the qualifications of union officers, demand the re-election of particular union officers, and inspect the daily operations of unions.

The revisions were a make-shift measure in the wake of the sudden onset of democracy and thus were incomplete by global standards. Labor laws still prohibited multiple unions both at the firm and national levels, the involvement of third parties in workplace industrial relations, and political activity by unions.

The behavior of the governmentwas still important after the onset of democratization. Neither employers nor workers had much experience with independent union activities and thus were not accustomed to abiding by laws. Under such circumstances, the government came to have strong discretionary power in judging the legality or illegality of particular behaviors of employers and unions. Though the government now pretended to act as a mediator between employers and workers, it is highly questionable that the government was unbiased. It was difficult for the government to be impartial simply on account of the inertia from the authoritarian period.

Meanwhile, individualworker protectionwas further strengthened. Dismissing workerswas mademore difficult, and the priority ofwage claims in bankrupt firms over other debt obligations was strengthened. More importantly, with democratization, employers were apparently under stronger pressure to abide by the labor laws set in place to protect individual workers.

Another revision of labor law was made after the foreign exchange crisis in 1997. The crisis was not a political change, but it was an event that ‘purged’ the elements of the system inherited from the authoritarian era. The IMF demanded the reform of industrial relations together with the reform of firms and financial institutions. The demands were eagerly complied with by the more liberal, if not pro-labor, government that took power at the beginning of 1998.

The change that was made in 1998 basically consisted in moving to a ‘global standard’ by ‘exchanging’ the lifting of remaining restrictions on unions and the weakening of the individual protections set up for workers. New labor laws lifted restrictions on the prohibition ofmultiple unions at the national – if not the firm–level, the involvement of third parties in union activities, and political activity by unions. The behavior of the government became less partial to employers with the emergence of more liberal governments, which ruled from 1998 to 2007.3 Arbitrary intervention was reduced. On the other hand, the protection of individual workers was weakened by making it possible to dismiss workers on the grounds of the poor financial performance of firms. It also made it easier for employers to recruit workers on short-term employment contracts.

In Korea, there has been no critical event that has led to a discontinuous break in the product market, at least after 1980, the period on which we focus here. The Korean product market was heavily regulated internally and protected externally in the 1960s and 1970s, but it was gradually liberalized from the early 1980s. The IMF demand for structural reform after the foreign exchange crisis in 1997 did not focus on liberalizing the product market. On the other hand, a drastic change occurred in the financial market, as radical structural adjustments and reforms were carried out after the 1997 crisis.

As in many developing countries, shareholder protection was weak in Korea before the 1997 crisis. Shareholders lacking 5% ownership could not remove a director, request an injunction, file a derivative suit, demand convocation, scrutinize a company’s books, or inspect company affairs or property. Few boards of directors performed the role of monitoring and disciplining managers. Hostile M&As were prohibited; in friendly M&As, only small firms were permitted as targets (Joh, 2004, pp. 204–205).

Creditors’ rights were relatively well protected in global standards (La Porta

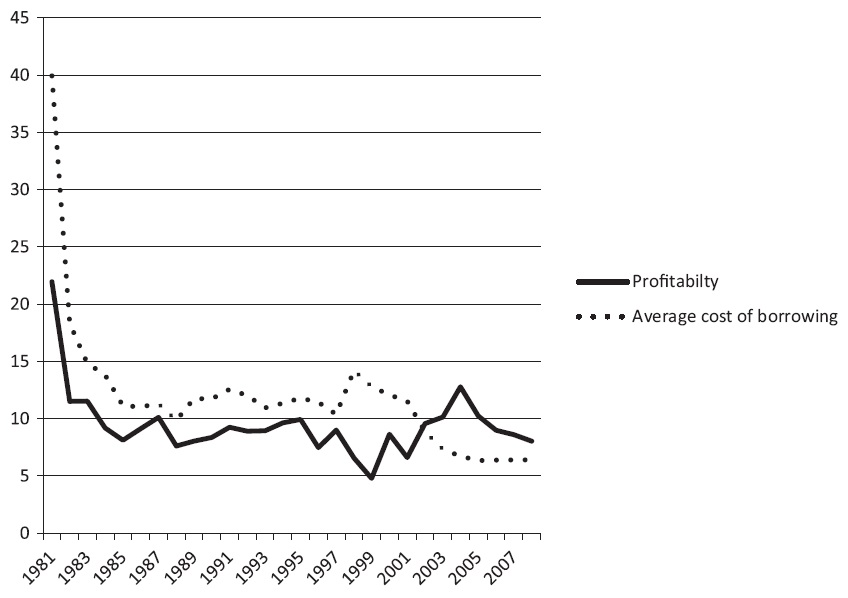

This is illustrated in Figure 1, which presents the average ‘operating profitability’ (the operating income divided by the operating capital; explained later) and the average of the average cost of borrowing for all firms listed in Korea’s stock exchange, whose data we will use in the analysis below. Before the crisis, on average, operating profitability consistently fell short of the average cost of borrowing. Korean firms were ‘destroying shareholder value,’ which confirms that shareholder protection was weak.4 It also means that, as long as the operating profit is uncertain incomewhile the cost of borrowing is a sure obligation, Korean firms were chronically producing non-performing loans (henceforth NPL), which confirms that they were under a soft budget constraint.

The weak shareholder protection and soft budget constraint may have provided a favorable condition for unions. If unions lower firm profitability due to this favorable condition, they are also contributing to the creation of the situation illustrated in Figure 1.Of course, shareholder protection was not completely weak, nor was the budget constraint completely soft. Moreover, employers, who were often controlling shareholders, were exploiting the weak shareholder protection and soft budget constraint to maximize their personal gains in the long run. They may have well regarded unions as a stumbling block, preventing them from attaining this goal. However, their resistance to the demands of the unions were likely to be weaker compared to when they were under strong shareholder protection and hard budget constraints.

The structure that chronically produced NPL was unsustainable, and as it was combined with the high debt-to-equity ratio of Korean firms before the crisis,was certain to precipitate a major financial crisis.5 The financial crisis broke out in early 1997 andwas extended to the foreign exchange crisis in late 1997. During the crisis, which spanned 1997 and 1998, more than 20,000 bankruptcies occurred, including those of approximately one-third of the banks. As a result, the budget constraint on firms and banks was suddenly hardened (Alexeev and Kim, 2008).

Alongside these bankruptcies, IMF-mandated radical reforms were carried out to strengthen shareholder protection and harden the budget constraint on firms. Shareholder protection was strengthened by activating boards of directors and audit committees and by making it possible for minority shareholders with 0.01% of a firm ownership to file derivative suits against managers. Hostile M&As, at least

The increased foreign share ownership also helped to strengthen shareholder protection and harden the budget constraint. By 2004, as high as 44% of listed companies, in terms of market value, were owned by foreign capital, one of the highest rates in the world. All major banks, except the one owned by the government, have come to be majority-owned by foreign capital.

As a result, the financial situation of firms has improved. As shown in Figure 1, since 2002, on average, operating profitability has consistently exceeded the average cost of borrowing. Korean firms are no longer destroying shareholder value or chronically producing NPL.

The strengthening of the financial market discipline for firms after the crisis meant the same thing for unions. Employers were expected to resist union demand more strongly as financial market discipline was strengthened. Moreover, the strengthening of the financial market discipline was combined with the weakening of the individualworker protection mentioned above: actually the purpose of the weakening of individual worker protection was to facilitate structural adjustments as well as to move to the ‘global standard.’ As a result, hundreds of thousands of workers lost their jobs, and the remaining workers were less sure of their job security. In addition, as it became easier to recruitworkers on short-term employment contracts, the share of ‘non-regular workers’ skyrocketed, accounting for 48.4% of employment by 2004 (Kim 2008, p. 182). This is likely to have weakened union bargaining power to the extent that unions represent – at least thus far – the interest of regular workers.6

If the strengthening of financial market discipline after the crisis weakened the union effect on profitability, it may have contributed to the improvement of the financial situation of firms, as illustrated in Figure 1.

2The description of the political environment here is a summary of contents of the Korea Development Institute (2010, Chapter 6), the Korea Labor Institute (2000), Kim (2004), Lee (2005), and Kwon and O’Donnell (1999). 3From 1998 to 2003, Korea was ruled by two consecutive liberal governments: the first was the Kim Dae-jung government, from 1998 to 2002, and the second was the Rho Mu-hyun government, from 2003 to 2007. 4This is consistent with the fact that the rate of return on stock ownership was lower than that of bond ownership before the crisis (Korea Development Institute, 2007, pp. 163–164). 5There is no doubt that the debt-to-equity ratio of Korean firms was high before the crisis. For example, the average debt-to-equity ratio in the manufacturing sector as of the end of 1995 was 287% in Korea, while it was 160% in the US, 206% in Japan, and 86% in Taiwan. The ratio fell drastically after the crisis: the average debt-to-equity ratio of the manufacturing sector amounted to 107% as of the end of 2007 (Source: The Bank of Korea: http://ecos.bok.or.kr). 6One may surmise that a higher ratio of non-regularworkers is the result of the bargaining power of unions, representing the interest of regular workers. There is indeed debate about this (Eun, 2007, pp. 11–14; Kim, 2003). However, in the comparison of the union effect between the periods, the revision of the laws to make the hiring of non-regular workers easier and the subsequent rise in the ratio of non-regular workers should have weakened union bargaining power.

3. Analytical Framework, Data, and Definitions of Variables

3.1 Analytical Framework and Data

It is clear from the above discussion of political and economic environments that there were two major breaks between 1981 and 2007, the period discussed here (the analysis is confined to the 27 years from 1981 to 2007, as explained below). The first is the onset of democracy in 1987, and the second is the foreign exchange crisis in 1997. We thus divide the 27 years from 1981 to 2007 into three periods using an interface of political and economic environments:

The years 1987, 1997, 1998 and 1999 are excluded because our major concern does not includewhat happened during the yearwhen the transition to democracy occurred or the years when the economy was in crisis. The year 1999 is included in the crisis period because firm bankruptcies continued in spite of the recovery of the economy.

During the authoritarian period, political environment was repressive while financial market discipline was weak. The repression may have made unions unable to have bargaining power. However, if the repression failed to deprive unions effectively of all the bargaining power, they could have lowered profitability given the strong individual worker protection and weak financial market discipline. What the net effect was is a matter for empirical investigation.

During the democratization period, the repressionwas lifted, though with some limitations, and individual protection was strengthened. Meanwhile, shareholder protection remained weak and budget constraints soft. Unions are thus likely to have lowered profitability. If unions indeed turn out to have lowered profitability, they contributed to the production of NPL and thus were responsible for the crisis.

In the post-crisis period, the extension of union rights and the incumbency of liberal governments provided unions with a better political environment. On the other hand, the weakening of individual worker protection together with the strengthening of financial market discipline should have made unions care for job security for their members.What the net effect was is again a matter for empirical investigation.

Our sample consists of the firms listed on Korea’s stock exchange, excluding financial firms and state enterprises. The Korea Listed Company Association provides the financial statement data of the listed firms (the data are the sources of the figures in Figure 1). The union data, which are not provided by the Association, are from the

There are several reasonswhywe analyze the union effect on profitability rather than the union wage premium, which is more commonly used in the industrial relations literature.

First, there are no data by which we can analyze the union wage premium consistently from the authoritarian period to the post-crisis period.

Second, in Korea, there are various forms of non-wage compensation to workers, such as subsidized school fees and housing benefits, especially after democratization. These benefits are not easily captured by the union wage premium. Firms also subsidize the expenses of unions, such as office rents and staff salaries, to a considerable extent, which is naturally not captured by the union wage premium.

Third and most importantly, the union effect on profitability is better than the union wage premium for an analysis of industrial relations under different political and economic environments. The analysis of the union wage premium cannot take the effects of unions on productivity into account. Unions may affect productivity as well as wages, though evidence on the union effect on productivity is less clear than the union effect on wages (Doucouliagos and Laroche, 2003; Metcalf, 2003). If the union wage premium is positive due to the positive effect of unions on productivity, profitability is not affected. In such a case, managers (in this case representing shareholders) will not resist much. On the other hand, managers will resist the union wage premium in excess of the union effect on productivity. The union effect on profitability thus represents the degree of the ‘conflict of interest’ between workers and managers, or, in a more classical term, ‘class struggle,’ better than the union wage premium. How that conflict of interest is handled under different political environments is the major concern of this paper. The union effect on profitability is also better than the union wage premium for the analysis of how unions and managers behave under different levels of financial market discipline. If unions raise wages but this does not affect profitability, it will not be a matter ofmuch concern for shareholders or creditors. Financial market discipline imposed on firms will thus communicate itself to the union effect on profitability rather than the union wage premium.

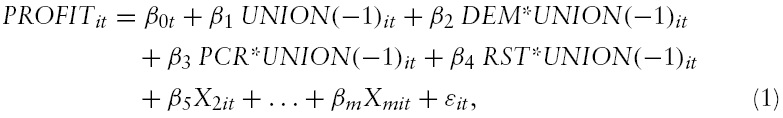

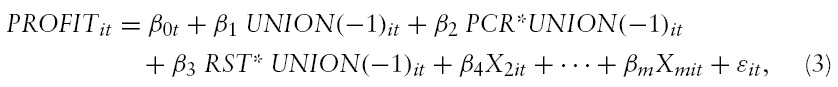

The regression equation is specified as follows:

The coefficient

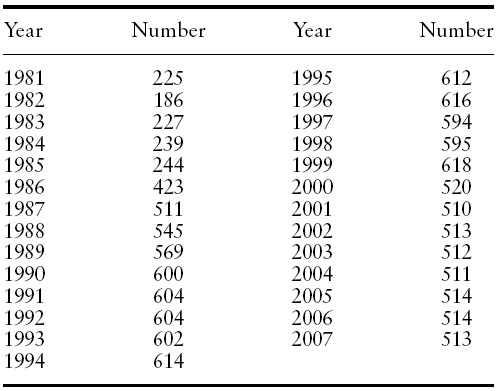

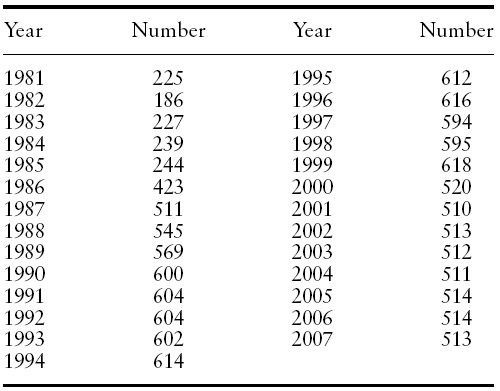

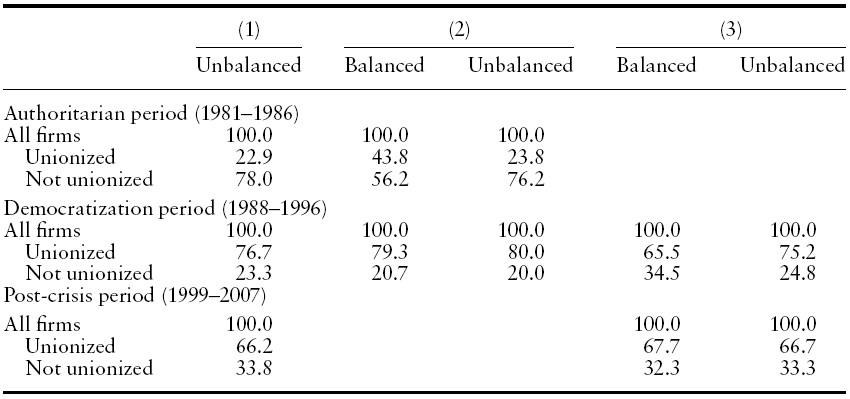

The problem with estimating Equation (1) is that there are large differences in the sample firms across the years from 1981 to 2007 due to the entry and exit of listed firms. Even among the listed firms, financial statement data are missing for some years from 1981 to 2007. Table 1 presents the number of listed firms with complete data. The number of listed firms with complete data increased drastically in the 1980s and then stayed somewhat stable in the 1990s. It fell in 2000 and then stabilized subsequently.

[Table 1.] Number of listed firms with complete data

Number of listed firms with complete data

Because of the data situation, it is impossible to construct a balanced sample across all of the years from 1981 to 2007. This is a problem because, for a strict comparison of the union effect on profitability between the periods, we need balanced samples. Balanced sample estimation is possible to a limited extent. We can construct two sets of balanced sample data: the first containing the data from 1981 to 1996, which makes a comparison between the authoritarian and the democratization periods possible, and the second containing the data from 1988 to 2007, which makes the comparison between the democratization and the post-crisis periods possible. Then, we can compare the two estimations to make some indirect comparisons between the authoritarian and the post-crisis periods.

The regression equation using the panel data from 1981 to 1996 is specified as follows:

Here,

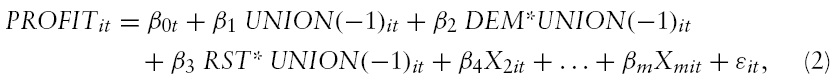

The estimation equation for the years from 1988 to 2007 is as follows:

Here, the democratization period is the base, and

We conduct unbalanced sample estimation as well as balanced sample estimation for Equations (2) and (3). The former will help to check the robustness of the results obtained for each period.

A fixed effects model is used for all estimations of the panel data. As software, E-View 5.1 is used.

3.2 Definitions of the Variables

There are two ways to define profitability: return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE) (Copeland

Operating income is the profit accruing as a result of the main business activities of the firm and operating capital is the amount of the assets put into those activities. Operating income does not include income on investment assets; thus, we have to subtract investment assets from total assets to obtain operating capital. Deferred assets, assets on construction, and machinery in transit also have to be subtracted because they are not used for the purpose of generating operating income.

The unionization variable is defined as follows:

The union data provided by the Ministry of Labor do not give consistent information about union density (organization ratio) for the 27 years from 1981 to 2007. Only the data about whether a firm was unionized or not is available. This data may not necessarily be inferior to the union density data considering that, once unions exist, non-members can benefit from their bargaining power.To minimize the simultaneous equation bias, we use the presence of unions as of the end of the year preceding the year analyzed as a sample. Thus,

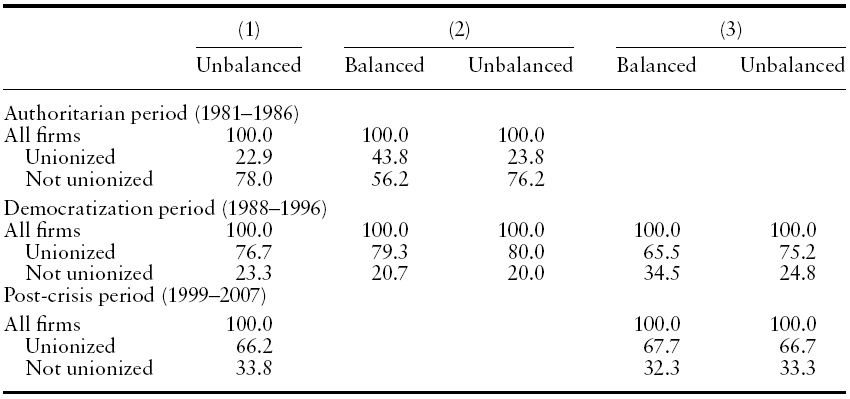

Table 2 presents the composition of the samples in the panel data used in the estimation equations explained above. The table shows the ratio of unionized firms in each of the three periods. The ratio of unionized firms is an important indicator of the strength of the labor movement. It will be affected by the political and economic environments discussed above. The ratio indeed rose drastically with democratization,whereas it did not change remarkably with the crisis.However, an analysis of those changes is beyond the scope of this paper.We focus here on how the existing unions affect firm profitability.

Determinants of profitability other than the unionization variable, which are denoted as

[Table 2.] The composition of samples

The composition of samples

The first of them is the firm size. We represent firm size with the amount of total assets using log values instead of absolute values, as is usually done:

Larger firms may enjoy economies of scale and a higher market share and may therefore show higher profitability. However, before the crisis, larger firms may have been subject to weaker financial market discipline, with poorer corporate governance and a softer budget constraint.Whether larger firms had higher profitability before the crisis is thus a matter of empirical test. On the other hand, after the crisis, the IMF-mandated reforms to improve corporate governance and harden budget constraints particularly targeted larger firms. As a result, larger firms enjoying economics of scale and higher market sharemay showhigher profitability after the crisis. To take this into account, we use dummy variables with the pre-crisis period (from 1981 to 1996) as the base.

The next variable is:

Advertising may work as a barrier to entry, or the value of total assets used as the denominator in defining

Another variable related to entry barriers is:

Large amounts of fixed assets relative to sales may impose an entry barrier by increasing the minimum amount of capital required to do business. On the other hand, a higher

Another variable is the dummy variable representing the percentage of foreign share ownership:

Firms with high foreign share ownership are likely to have better corporate governance and harder budget constraints. However, as in the case of the firm size, the effect of foreign share ownership on profitability may be different between the pre-crisis and post-crisis periods. Before the crisis, firms with high foreign share ownership are likely to have been less characterized by the poor corporate governance and soft budget constraints. After the crisis, foreign share ownership may have become a ground for further improving corporate governance and strengthening budget constraints. Alternatively, domestically owned firms may also have improved corporate governance and hardened budget constraints so that foreign share ownership may not matter after the crisis. To test these possibilities, we include

Finally, dummy variables representing industries are included. Industries are classified into 10 sectors: primary, light manufacturing, heavy and chemical manufacturing, construction, electricity, communication, sales, transportation, personal and business service, and ‘the other.’ Nine dummy variables representing the first nine industries in this list (excluding ‘the other’) are included.

This list of variables is of course short of the comprehensive list of the determinants of firm profitability. However, as long as our major concern is to identify the union effect on firm profitability, it may not be a serious problem unless some variables highly correlated with the union variable are left out. It is not easy to imagine that there are such variables left out.

7A variable related to the firm size is the affiliation with chaebol, Korean business conglomerate. Several studies have shown that chaebol firms had especially weak shareholder protection and soft budget constraints before the crisis (Joh, 2003; Krueger and Yoo, 2001). On the other hand, the crisis and reforms affected chaebol firms more heavily. Unfortunately, the variable denoting chaebol affiliation is too highly correlated with the firm size variable, causing a serious multi-collinearity problem when both variables are included. The regressions using the chaebol variable instead of the size variable give exactly the same results.We thus focus here on the analysis with the firm size variable.

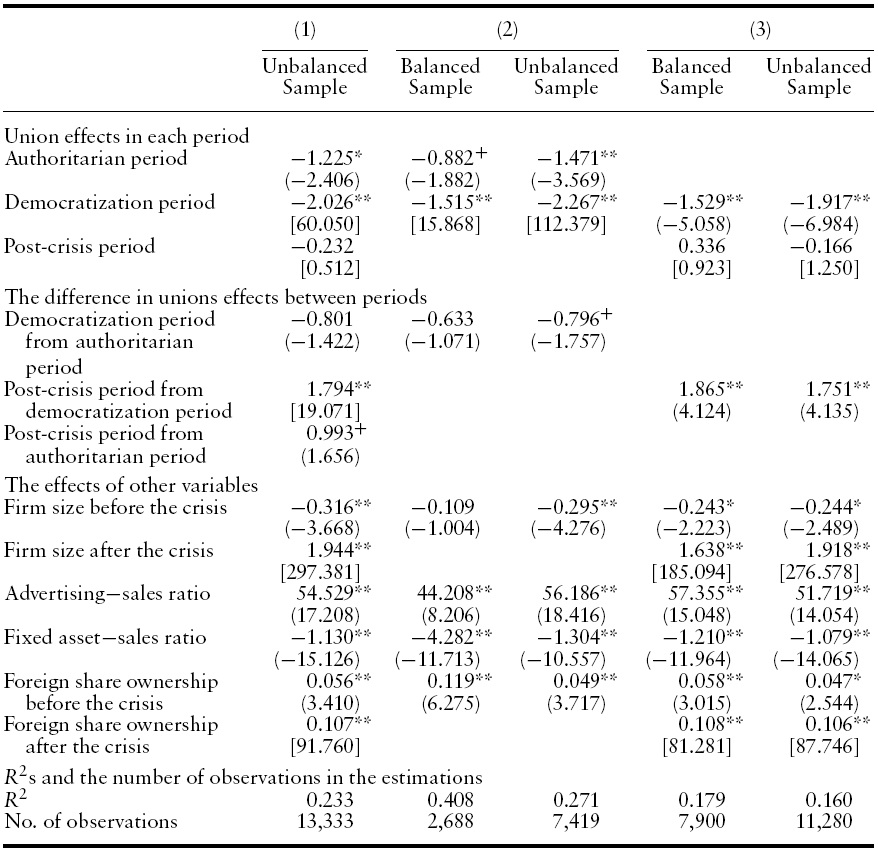

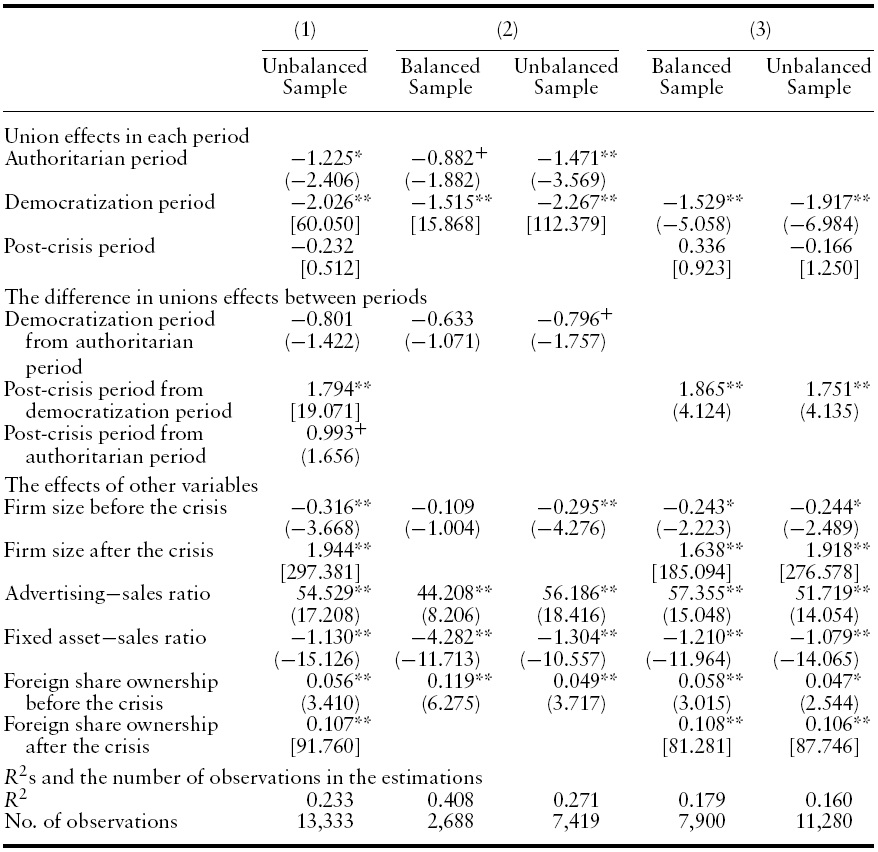

We do not present the estimation results directly, considering that the coefficients in the regression equations do not necessarily capture the union effect on profitability by themselves. Instead,we present the estimated coefficients for the union effects on profitability in each period and the difference between the periods. Table 3 presents those results, together with the estimated coefficients for the other determinants of profitability and R2 and number of observations for each of the estimations. The direct estimation results are presented in the Appendix

[Table 3.] The effects on firm profitability: Unions and other variables

The effects on firm profitability: Unions and other variables

In Table 3, some figures pertaining to the union effect come directly from the estimations. For example, the union effect in the authoritarian period is directly from the estimation of Equations (1) and (2), and the union effect in the democratization period is directly from the estimation of Equations (3).To determine their statistical significance,

In the authoritarian period, the union effect on the profitability is significantly negative. The effect of repression was dominated by the effect of weak financial market discipline.What transpired is that the repression failed to deprive unions effectively of all bargaining power, and once unions had some bargaining power, they could lower profitability given the strong individual worker protection and weak financial market discipline.

In the democratization period, the union effect on profitability is also significantly negative. Not surprisingly, unions significantly lowered firm profitability during the democratization period, by a larger margin than in the authoritarian period. These estimation results imply that unions are responsible for the crisis by contributing to the production of NPL: they lowered profitability so that profitability fell below the average cost of borrowing, as described in Figure 1.

In the post-crisis period, unions do not lower firmprofitability any longer. This suggests that the effect of weakened individual worker protection and strengthened financial market discipline dominates that of the strengthened union rights and the installation of liberal governments. Now, unions are apparently putting priority on the job security of their existing members rather thanwage hikes. This is consistent with the pattern of strikes. After the crisis, major issues of strikes are job security rather than wage hikes (Choi and Kim, 2004). This absence of the union effect on profitability contributed to the better financial situation of firms from 2002, as illustrated in Figure 1. Now unions are not on average contributing to the production of NPL.

Table 3 shows that there is not so robust a difference in the union effects on profitability between the authoritarian and democratization periods. With the onset of democracy, the ratio of unionized firms rose drastically, as shown in Table 2. However, the union effect on profitability failed to rise as drastically. It rose marginally fromthe effect already existing in the authoritarian period.Onthe other hand, there is a strongly significant difference between the democratization and post-crisis periods in all estimations.The crisis did not lead to a drastic change in the ratio of unionized firms, as shown in Table 2, but it drastically reduced the effect of existing unions on profitability. This suggests that the effect of the weakening of individual worker protection and the strengthening of financial market discipline dominates that of the strengthening of union rights and the installation of liberal governments.

As for the difference between the authoritarian and the post-crisis periods, direct test is possible only for the unbalanced sample estimation of Equation (1). Unions turn out to lower the profitability significantly less in the post-crisis period than in the authoritarian period.Aguess is also possible fromthe balanced sample estimations of Equations (2) and (3). Democratization failed to raise the union effect on profitability clearly, while the crisis reduced that effect dramatically, implying that the union effect on profitability before the two ‘big breaks’ is larger than that after them.

It is interesting that unions lower profitability in the authoritarian period, but they fail to do so in the post-crisis period. Political repression is less effective than weak individual worker protection combined with strong financial market discipline in eliminating the union effect on profitability. Even such an authoritarian state as Korea’s Fifth Republic could not eliminate that effect. In contrast, weak individual worker protection and strong financial marker discipline in the post-crisis period managed to eliminate that effect. In otherwords, inKorea, ‘neoliberal’ institutional arrangements which weakened individual worker protection and strengthened financial market discipline were more effective than political repression in eliminating the union effect on firm profitability.

In relation to this, it should be noted that the lack of a significant union effect on profitability in the post-crisis period is unlikely to be the result of cooperative industrial relations. There is a strong reason to believe that Korean industrial relations are far fromcooperative, though theremay be rare exceptions. Theywere conflict-ridden before the crisis, as employers attempted to exploit the repression and government partiality to the greatest extent possible and unions resisted those attempts. After the crisis, the government took some steps tomake the relationship more cooperative by establishing the ‘Tripartite Commission’ after the model of European countries, but this effort did not succeed in enacting a ‘grand bargain.’ Thus, the lack of the union effect on profitability after the crisis is most likely the result of an increased threat to the job security of union members rather than the emergence of cooperative industrial relations.

Table 3 also presents the estimation results for the other determinants of profitability than the unionization variable. The effect of firm size on profitability before the crisis is negative in all estimations, with statistical significance except in the balanced sample estimation of Equation (2). This suggests that the effect of weak financial market discipline was stronger than the effect of economies of scale or the market share before the crisis. On the other hand, after the crisis, the effect of firm size on profitability is significantly positive in all estimations. Larger firms have higher profitability, apparently due to the economies of scale and larger market share under the strengthened financial market discipline. Meanwhile, advertising-sales ratio has positive coefficients with strong statistical significance in all estimations, as expected. Fixed asset-sales ratio has significantly negative coefficients in all estimations, implying that the turnover ratio effect of fixed assets outweighs possible entry barrier effects. Foreign share ownership before the crisis has significantly positive effects on profitability in all estimations, as expected. The effect of foreign share ownership on profitability is also significantly positive in the post-crisis period. Actually, the effect of foreign share ownership on profitability is significantly stronger after the crisis than before the crisis, as shown by the fact that

We have analyzed the union effect on profitability under different political and economic environments using the data of Korea’s listed firms. This was done through a regression analysis using unionization as a determinant of profitability during the authoritarian period, the democratization period, and the post-crisis period.

In the authoritarian period, unions did lower firm profitability. Repression failed to deprive unions effectively of all of their bargaining power, and thus unions lowered profitability under the conditions of strong individual worker protection and weak financial market discipline. During the democratization period, unions clearly lowered firm profitability. During the post-crisis period, unions did not lower firm profitability, apparently because of the weakened individual worker protection and strengthened financial market discipline.

The union effect on firm profitability increased marginally with democratization but decreased sharply with the crisis. This implies that ‘neo-liberal’ structural adjustments and reforms were more effective than political repression in eliminating the union effect on profitability.

Our motivation in this paperwas to overcome the dearth of studies of the union effect on profitability under different political and economic environments. We have particularly attempted to present the first analysis of the union effect on profitability under authoritarian and democratic political regimes in developing countries.We have also tried to add to the body of research on the union effect on profitability under different financial market conditions. Some results obtained in the paper are apparently new, given the state of existing studies.

However, the analysis of the paper is rudimentary and has many limitations. For example, we observed that the lack of the union effect on profitability after the crisis is most likely the result of the weakened individual worker protection and strengthened financial market discipline rather than the emergence of cooperative industrial relations. This interpretation of the Korean situation will raise some questions to those who are familiar with international differences in the union effect on profitability. In the US, financial market discipline is stronger and individual protection is weaker than in European countries. However, the union effect on profitability is larger in the US, probably due to the less cooperative industrial relations (Doucouliagos and Laroche, 2009). We cannot pursue this problem in depth here. One plausible explanation is that Korean workers after the crisis faced a situation different from that of US workers. Korea underwent a massive bankruptcy of firms and dismissal of workers after the 1997 crisis, but the Korean labor market was far less ‘flexible’ than in the US, and the social safety net was close to being absent. If dismissed from their current jobs, Korean workers were likely to find that their alternatives were unemployment with little social protection, simple laboring jobs, or petty selfemployment. However, whether this explanation is correct is beyond the scope of this paper.

Our analysis also failed to take into account conditions such as the competitiveness of the product market.We did not deal with product market conditions given the absence of a visible break in these conditions in the period from 1981 to 2007. However, a more practical reason is the lack of data. Given better data, a better analysis would be possible by encompassing the effect of the competitiveness of the product market.