Low-value, or trash fish (i.e., as raw ingredients not reduced to fishmeal), is a term used to describe fish species with various characteristics, generally including fish that are small in size and have little or no direct commercial value (Funge-Smith et al., 2005). The FAO (2012) estimates that the total worldwide volume of low-value fish used as feed in aquaculture is approximately 9 million tons. The use of low-value fish as feed is a common husbandry practice in marine fish farms in several countries within the Asia-Pacific region (Funge-Smith et al., 2005). Approximately 90% of the marine fish (e.g., Korean rockfish) cultured in Korea are fed with farm-made aquafeed, whose formulation generally consists of low-value fish mixed with 10–20% (w/w) industrially manufactured compound fish meal feed (Kim et al., 2013). Although accurate information about the exact species of low-value fish used as feed in Korea is lacking, Pacific sand eel

>

Bacterial isolation and identification

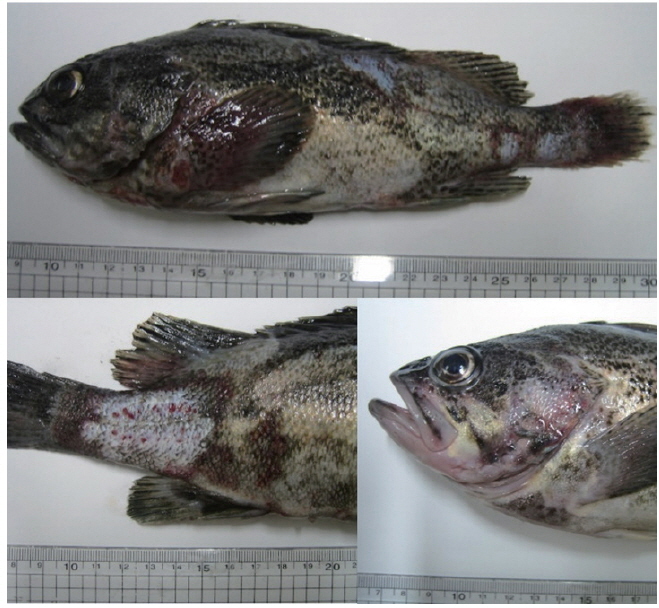

Infected Korean rockfish

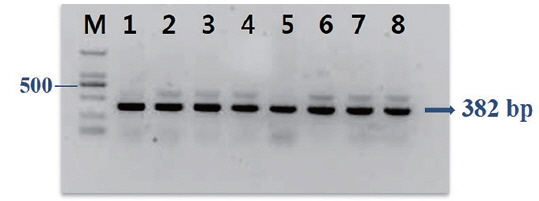

Frozen low-value fish samples were thawed quickly in a microwave oven, and the kidney and liver were aseptically removed and used to isolate bacteria. Several colonies with different morphologies appeared on BHIA after a 7-d incubation at 25℃. A colony polymerase chain reaction was then performed on each well-isolated colony using 16S rRNA gene primers (f D1: 5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′; rP2: 5′-ACGGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) (Weisburg et al., 1991), following the procedure described in Kim and Kim (2013). Sequencing reactions were conducted using a BigDye Terminator v.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and the amplified DNA fragments were sequenced on an automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems 3730xl DNA Analyzer). Specific primers (toxRF1 5′-GAAGCAGCACTCACCGAT-3′; toxRR1 5′-GGTGAAGACTCATCAGCA-3′) amplifying a part of the

>

Analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequences

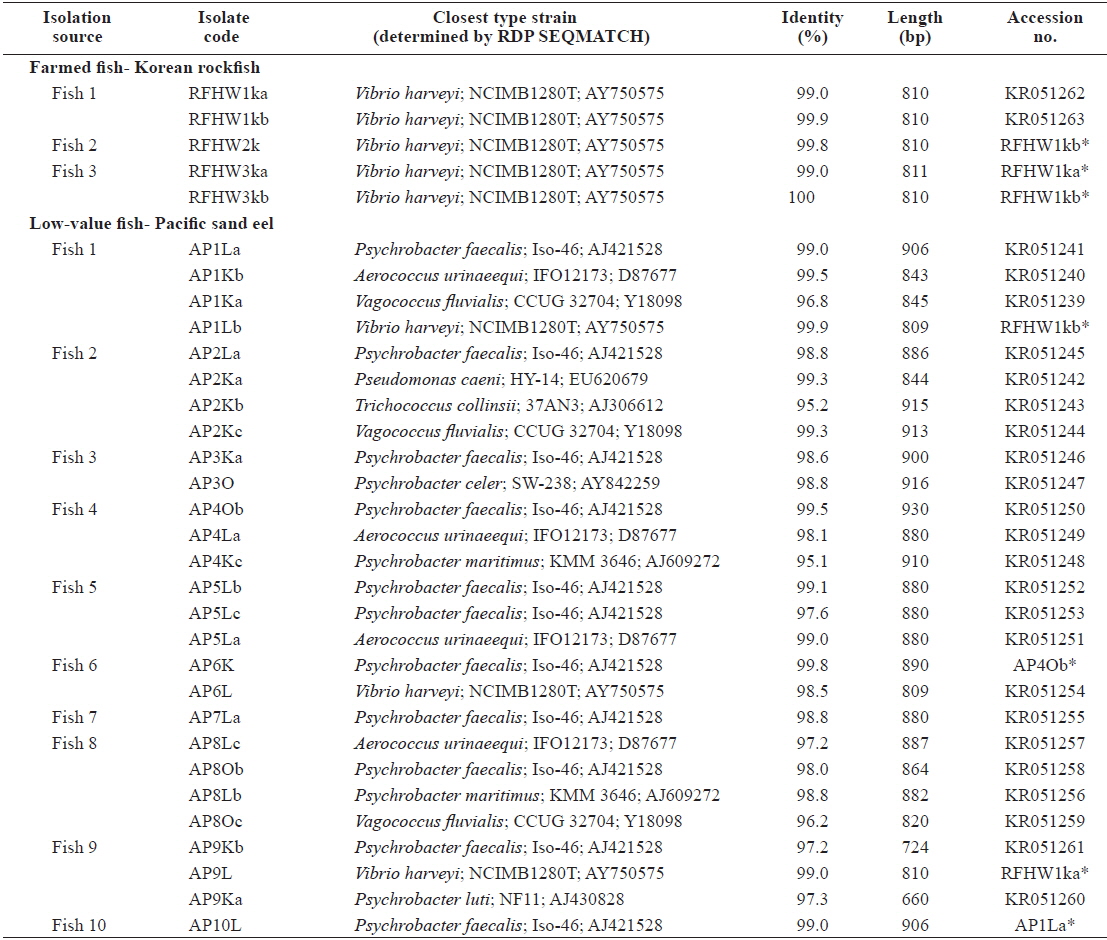

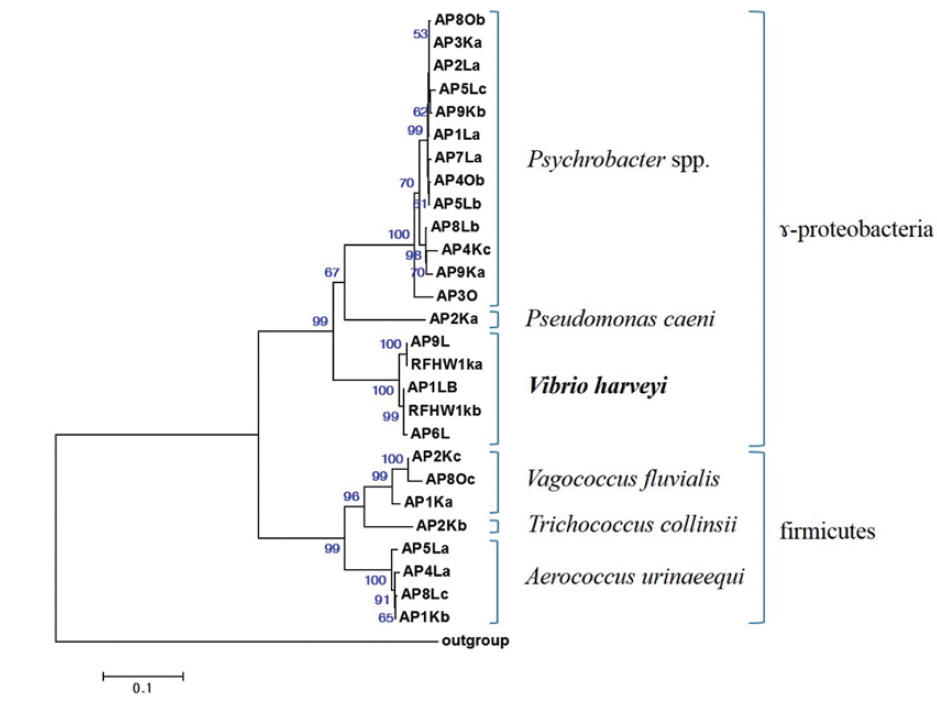

All sequences were subjected to similarity searches using BLAST, and the closest type strain was determined using RDP SEQMATCH (www.rdp.cme.msu.edu) (Cole et al., 2009). The sequences of all isolates were aligned using the ClustalX software for phylogenetic analysis, and positions 63–779 (

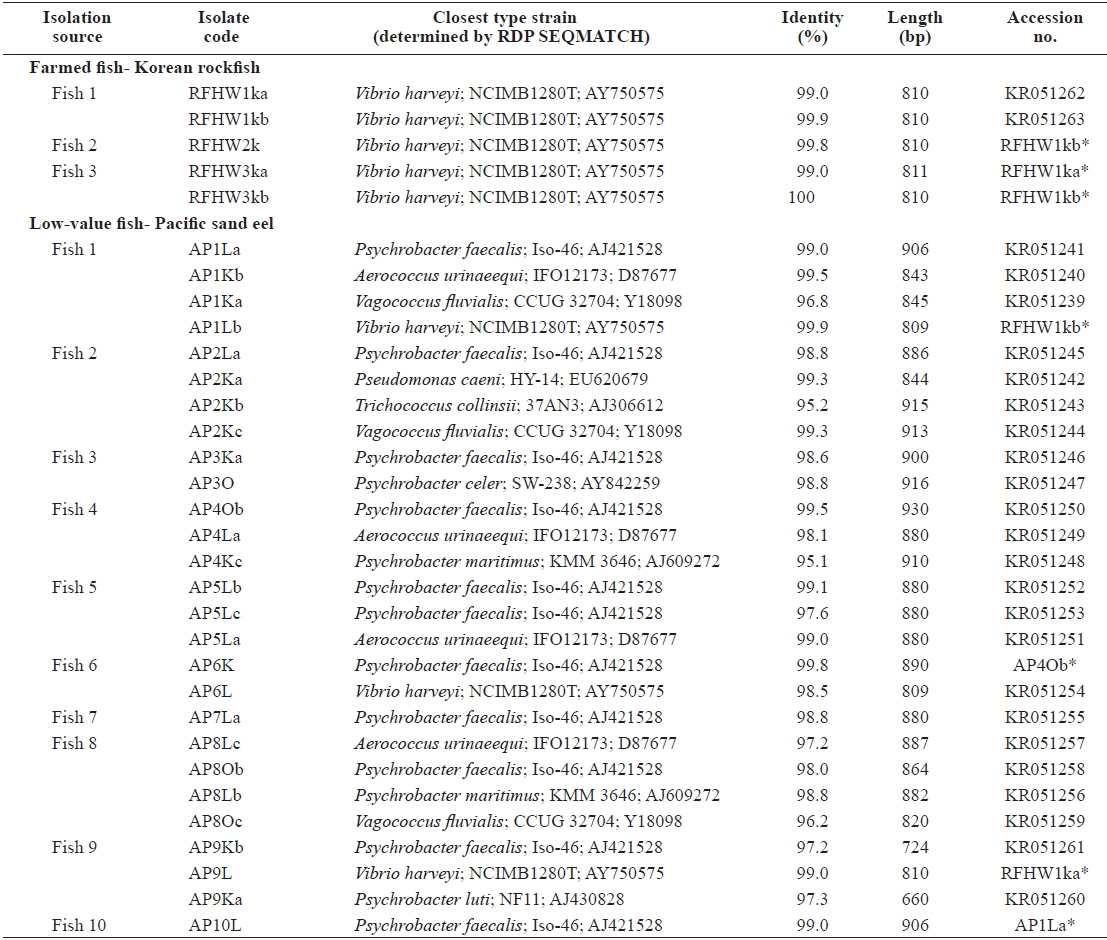

Representative sequences (16S rRNA gene) of isolates obtained from the internal organs of pacific sand eel Ammodytes personatus and infected Korean rockfish Sebastes schlegeli.

>

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

A disc diffusion assay was performed for all isolates and reference strains according to the protocols specified in the CLSI guideline M42-A (CLSI, 2006). All tests were conducted on Mueller–Hinton agar supplemented with 1% NaCl, with incubation at 22℃ for 24–28 h. Eight antimicrobials, including discs containing gentamicin (10 μg), erythromycin (15 μg), florfenicol (30 μg), nalidixic acid (30 μg), oxolinic acid (2 μg), enrofloxacin (5 μg), oxytetracycline (30 μg), and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (SXT) (1.25/23.75 μg) (Oxoid, Cambridge, UK) were used. These are all antibiotics that have been approved for use in aquaculture.

The closest type strains to the 32 isolates retrieved in this study and their accession numbers are listed in Table 1. The phylogenetic relationships are presented in (Fig. 2).

Most of the Korean rockfish sampled in this study displayed skin ulcers and hemorrhaging in the operculum and around the base of the pectoral and pelvic fins and the caudal peduncle (Fig. 1). Most of the bacteria isolated from the fish showed similar colony morphology; thus, five isolates were selected for further examination. The 16S rRNA gene sequences of the five selected rockfish isolates (RFHW1ka, RFHW1kb, RFHW2k, RFHW3ka, and RFHW3kb) and three Pacific sand eel isolates (AP1Lb, AP6L, and AP9L) were found to be most closely related to the

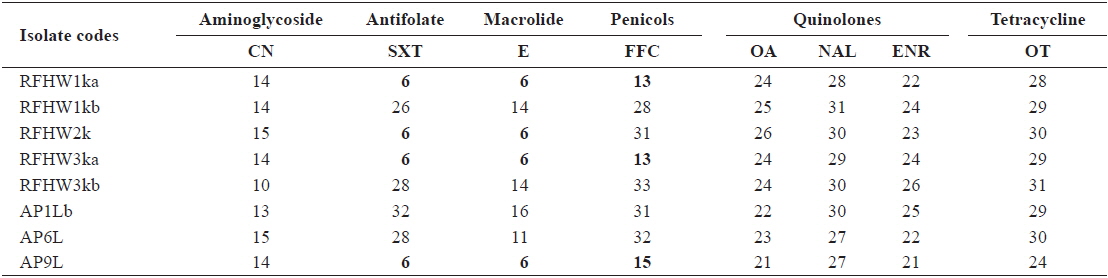

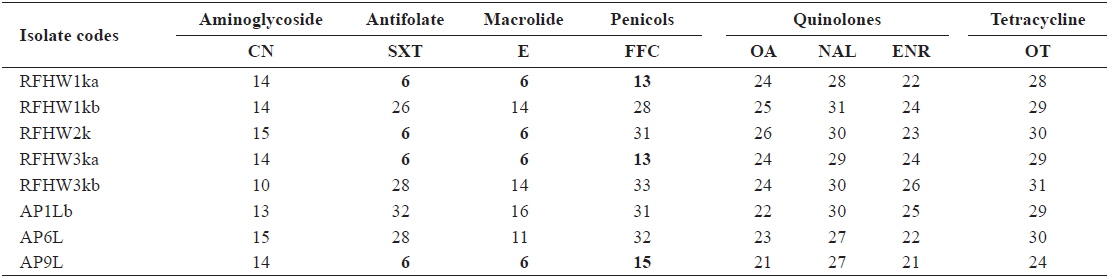

The inhibitory zones obtained for the reference strains were within the acceptable ranges specified in the CLSI guideline M42-A (CLSI, 2006). The zone sizes obtained from the

Inhibitory zone diameters (mm) of Vibrio harveyi isolates obtained from pacific sand eel Ammodytes personatus and infected Korean rockfish Sebastes schlegeli

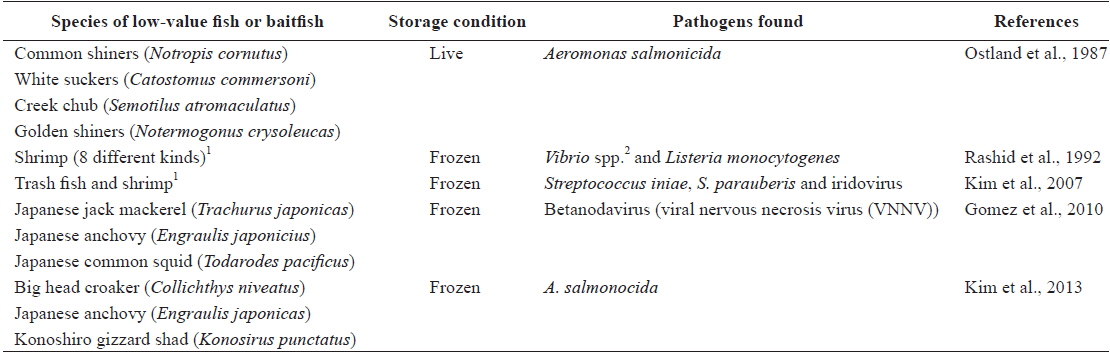

In general, the use of baitfish and low-value fish for feed raises the possibility of disease transmission (Gill, 2000; Hardy, 2004; FAO, 2011). Several studies have shown that baitfish or low-value fish pose significant risks for the spread of diseases, as summarized in Table 3 (e.g., Ostland et al., 1987; Rashid et al., 1992; Kim et al., 2007; Gomez et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2013). Low-value fish are often used in close proximity to their source; however, larger numbers of low-value fish captured from the wild are moved and released into new regions far from their origins (Goodwin et al. 2004). Indeed, frozen low-value fish are of particular concern, given evidence that freezing is insufficient to inactivate all of the viruses and bacteria present in infected fish (Arkush et al. 1998; Hervé-Claude et al. 2008; Kim et al., 2013). Thus, as described previously by Hyatt et al. (1997) and Ward et al. (2001), imported frozen whole feed fish could play an important role as a vector for the introduction and spread of exotic diseases. In light of this, many countries have restricted the use of low-value fish in fish farming activities. For example, the use of low-value fish is prohibited in Denmark, and fish farms have been forced to switch to formulated feeds. Re-feeding of salmon to the same species (intra-species recycling) is also banned by law in Norway and Chile (FAO, 2006). Finfish aquaculture activities in Korea still depend too much on low-value fish feed, so serious biosecurity concerns continue to exist in the country. Therefore, the introduction of new regulations to ban the use of whole low-value fish (containing internal organs) on Korean fish farms may be needed in the near future to ensure the sustainability of aquaculture, as well as protect the natural environment. Furthermore, as low-value fish or baitfish imported into Korea are not a designated quarantine item under current Korean law, legislation to require inspection of the imported fish to be used as aquaculture feed by a competent authority should be urgently introduced to minimize the occurrence of exotic diseases.

[Table 3.] Aquatic pathogens found in baitfish or low-value fish used as aquaculture feed

Aquatic pathogens found in baitfish or low-value fish used as aquaculture feed