Water is essential for the maintenance of biological homeo-stasis and provides a suitable environment for living organ-isms. Drinking water contains a number of components that are considered to be important to human health. Deep-sea water in Japan and Hawaii has gained attention for its benefi-cial effects on the cardiovascular system and hyperlipidemia (Ueshima et al., 2003; Yoshioka et al., 2003; Miyamura et al., 2004; Katsuda et al., 2008). However, the mechanisms under-lying these effects are not well understood. Deep-sea water is rich in mineral components, such as magnesium, calcium, and potassium, which act as essential cofactors in a number of bio-chemical processes. An insufficient supply of minerals caused by the civilized lifestyle and an imbalanced diet can cause ma-jor health problems, leading to lifestyle-related diseases, such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes (Havelaar and Melse, 2003).

Jeju province in Korea, which is a volcanic island, has char-acteristic geological features distinct from the mainland. Jeju possesses a clean groundwater resource because the volcanic Halla mountain acts as a water purification system as well as a huge water reservoir. Recently, we discovered a different wa-ter resource, ground seawater, which infiltrates to the surface of the east area of Jeju from the Pacific Ocean. The present study found that the mineral composition of this ground sea-water is similar to that of the deep-sea water of Muruto Cape (Kochi, Japan) (Miyamura et al., 2004). We prepared desalted water by electrodialysis (electrodialysed seawater [EDSW]) from ground seawater and investigated its biological effects in terms of ethanol metabolism, glucose uptake, and fat ac-cumulation.

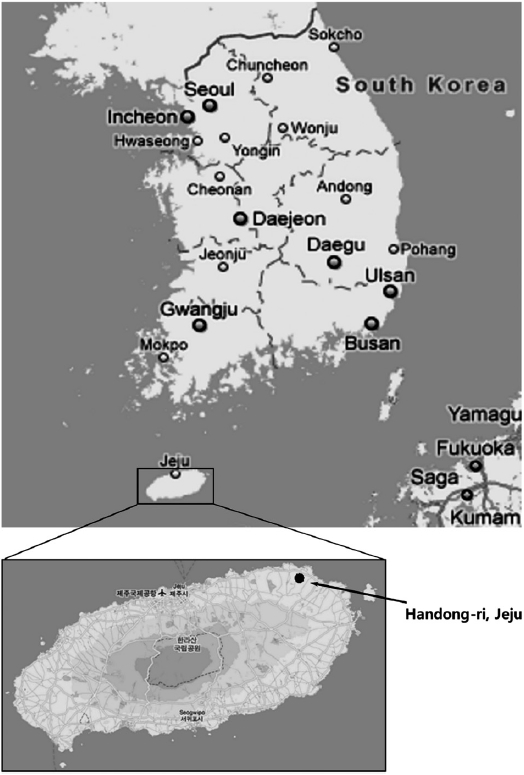

Ground seawater was pumped up from a depth of 130 m in Handong-ri, which is located 1.3 km inland from the northeast coast of Jeju (Fig. 1), Korea. Ground seawater was electrodia-lyzed using an electrodialysis system (CJTTS-2-10; Changjo Techno Co., Paju, Korea) to prepare EDSW deficient in mon-ovalent ion species, such as sodium, potassium, and chloride ions (Table 1). Three EDSWs with electroconductivities of 8, 10, and 12 mS/cm were prepared. However, the data presented herein were obtained using 12 mS/cm EDSW because the ma-jority of significant physiological activities in cells and ex-perimental animals were more pronounced with the use of this fraction (Koh et al., 2008). Mineral content analysis of ground seawater and EDSW was performed by a custom analytical service (Korea Testing and Research Institute, Seoul, Korea)

(Table 1). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) Ham’s F-12 medium, Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (D-PBS), trypsin-EDTA solution, and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were obtained from Life Technologies Inc. (Rockville, MD, USA). Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Electro-phoresis reagents, such as gels, Tris-glycine sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) running buffer, and poly(vinylidene difluoride) (PVDF) membranes were from Koma Biotech (Seoul, Korea). Other reagents were from Sigma Chemical Corp. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

HepG2 cells from human hepatoblastonema, Chinese ham-ster ovary cells which overexpress human insulin receptors (CHO-IR), and differentiated L6 rat skeletal muscle cells (L6 myotubes) were used. Cells were grown in DMEM (HepG2 and L6) or Ham’s F-12 medium (CHO-IR) containing 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, and 10% FBS, and maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air at 37℃. Cells were grown to confluence (2 × 106 cells/35 mm2) in 24-well (for lactate dehydrogenase [LDH] and MTT analy-sis) or 6-well (for oil red staining or Western blot analysis) plates and further treated with reagents.

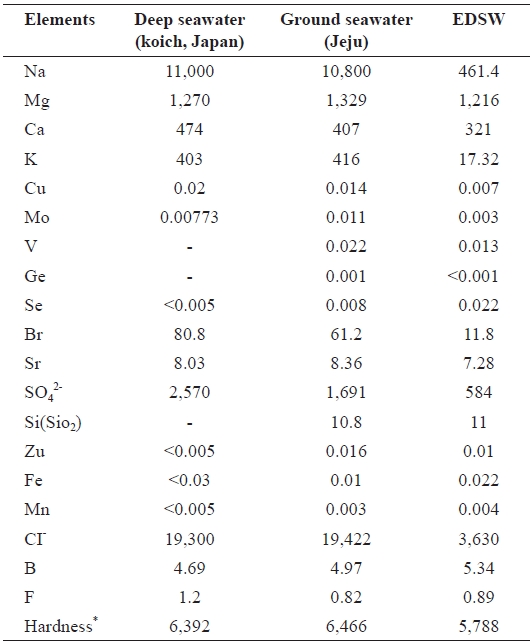

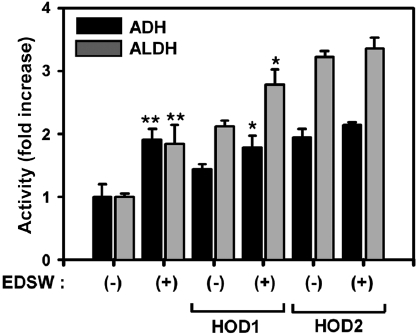

[Table 1.] Mineral contents of ground seawater and electrodialyzed, de-salted ground seawater (EDSW)

Mineral contents of ground seawater and electrodialyzed, de-salted ground seawater (EDSW)

Male three-week-old ICR mice were purchased from Central Laboratory Animal Inc. (Seoul, Korea). Mice were divided into four groups (

MTT analysis was performed as described previously (Mos-mann, 1983). Following treatment, media was removed from the wells, and 200 μL MTT reagent (Sigma) at a concentration of 1 mg/mL in RPMI-1640 medium without phenol red was added to each well. After 1 h incubation at 37℃, the cells were lysed by the addition of 1 volume 2-propanol and shaken for 20 min. Absorbance of converted dye was measured at a wavelength of 570 nm. Alternatively, cells were stained with a DNA-specific fluorescent dye (H33342) then observed under a fluorescent mi-croscope equipped with a CoolSNAP-Pro color digital camera (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA) to examine the degree of nuclear condensation. The quantity of LDH that had leaked from damaged cells into the culture medium was mea-sured using reagents from Takara (Otsu, Shiga, Japan).

>

Measurement of glucose consumption

Glucose consumption by L6 muscle cells during a 24-h in-cubation was measured without the use of radiolabelled 2-de-oxyglucose. The amount of glucose in the culture medium was measured using the glucose assay reagent (Sigma) before and after treatment, and the differences between groups were re-garded as the amount of glucose consumed by muscle cells. Data were normalized to protein levels.

>

Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) assay

ADH and ALDH activities were measured as described previously (Bostian and Betts, 1978) with minor modifica-tions. Briefly, S9 rat liver post-mitochondrial (cytoplasmic) homogenate (Moltox, Boone, NC, USA) was used as the source of ADH and ALDH fractions. S9 rat liver homogenate was dissolved in 0.1% bovine serum albumin and aseptically filtered. Two commercial hangover drinks (HOD1 and HOD2) were freeze-dried and used as positive test samples stimulat-ing ADH and ALDH activities. The reaction mixture used for the ADH assay consisted of 0.25 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 0.2 mM NAD+, 1.7 M ethanol, 5% (v/v) ADH fraction, and test samples (3 mg/mL, HOD1 and HOD2) dissolved in distilled water or EDSW. The mixture was incubated at 30℃ for 5 min, after which the absorbance at 340 nm was measured to determine the rate of NADH production. The ALDH assay reaction mixture consisted of 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.7 mM NAD+, 0.03 M acetaldehyde, 0.1 M KCl, 0.01 M 2-mercaptoethanol, 3% (v/v) ALDH fraction, and test samples (3 mg/mL, HOD1 and HOD2) dissolved in distilled water or EDSW. After incubation for 5 min at 30℃, the rate of NADH production from NAD+ was determined by measuring absorbance at 340 nm.

Intracellular fat droplets were stained with oil red. Briefly, cells were washed twice in D-PBS, fixed in 10% formalin for 10 min, and then stained with Oil Red O solution (0.3% in 60% isopropanol) for 10 min. Cells were washed in 60% iso-propanol and digitally imaged.

Unless otherwise indicated, cells were lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 1% nonidet P-40, 0.25% so-dium deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM sodium orthovana-date, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM aprotinin, 1 mM leupeptin, 1 mM pepstatin A). Identical amounts of proteins were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 4-20% polyacrylamide gels and elec-trotransferred onto PVDF membranes. Membranes were then incubated in blocking buffer (5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buff-ered saline [TBS]-0.1% Tween-20 [TBS-T]) for 1 h at room temperature and probed with different primary antibodies (1:1,000-1:5,000). After a series of washes, membranes were further incubated with different horseradish peroxidase-conju-gated secondary antibodies (1:2,000-1:10,000). Signals were detected with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection sys-tem (Intron, Seoul, Korea).

Results are presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical signifi-cance was determined by a Student’s

Mineral contents of ground seawater and EDSW were com-pared to those of the deep-sea water produced in Koich, Japan. There was little difference in the mineral compositions of the deep-seawater and ground seawater, except for the presence of oxidized silicon (SiO2) (10.8 mg/L) and negligible vanadium, germanium, and selenium content in ground seawater (Table 1). Hardness of the seawaters was also similar. In the 12 mS/cm EDSW, more than 80% of the monovalent ions sodium (96%), potassium (96%), and chloride (82%) were removed after electrodialysis.

>

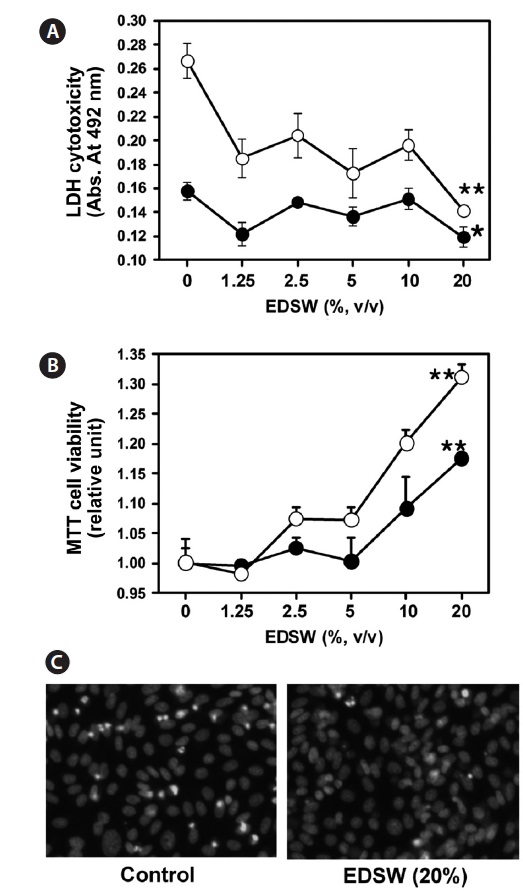

Effect of EDSW on cell viability

CHO-IR cells, which originated from non-tumorous epithe-lial cells (Tjio and Puck, 1958), were used to investigate any cytotoxic effects of EDSW. When CHO-IR cells were incu-bated in serum-free medium containing various EDSW doses for 48 h, MTT activity was significantly (

>

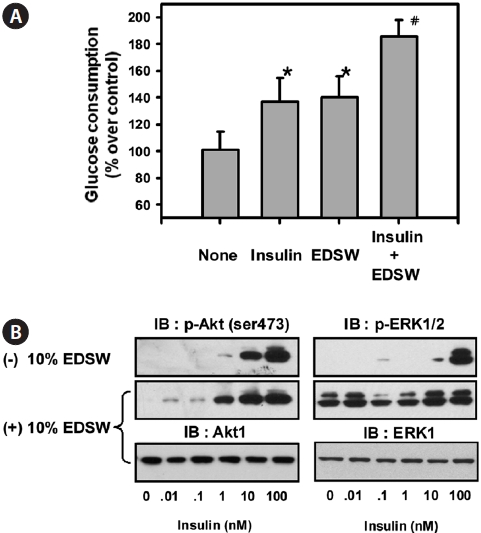

Effect of EDSW on glucose consumption in L6 muscle cells

Muscle is a primary target tissue for glucose transport through the actions of insulin receptors in the cell mem-brane, thereby contributing to the maintenance of normal blood glucose levels. We examined whether EDSW affects basal- or insulin-dependent glucose consumption in L6 muscle cells. The addition of 10% EDSW significantly (

>

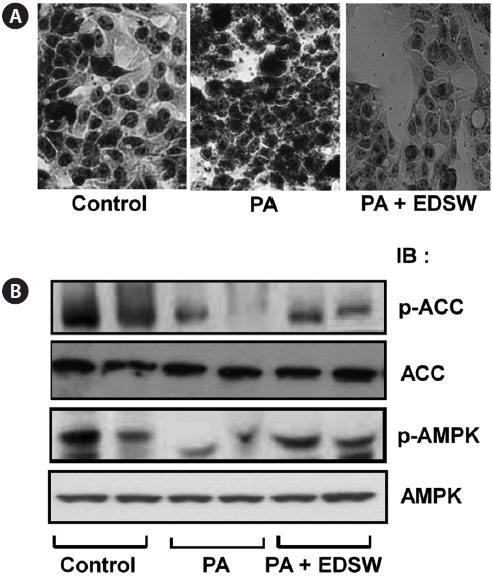

Effect of EDSW on ADH and ALDH

ADH and ALDH activities were measured using S9 rat liver homogenate enzymatic fractions (Fig. 4). EDSW stimu-lated basal activities of both enzymes by almost two-fold (

>

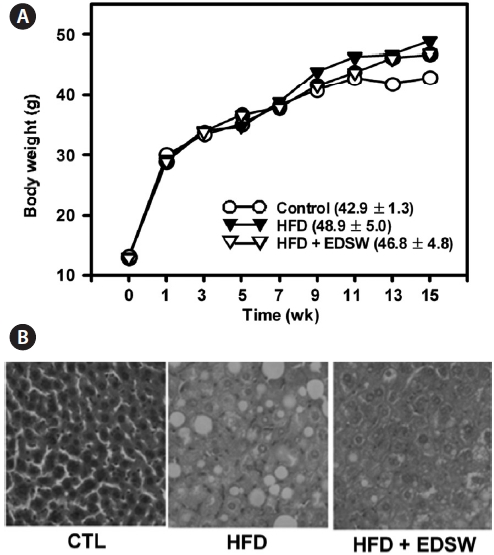

Effect of EDSW on lipid metabolism in HepG2 cells

Incubation of HepG2 cells in medium containing a 0.5 mM palmitate:oleate mixture (1:2) for 24 h induced intracellular fat accumulation (Fig. 5A). However, addition of 10% (v/v) EDSW to the culture medium suppressed the palmitate:oleate mixture-induced fat accumulation. We then determined wheth-er EDSW affects AMP-stimulated protein kinase (AMPK) and acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC) activities, two key enzymes in intracellular triglyceride biosynthesis in HepG2 cells. Phosphorylation of AMPK and ACC was suppressed after treatment (2 h) with the palmitate:oleate mixture (Fig. 5B).

However, EDSW (10%, v/v) restored the palmitate:oleate mixture-induced suppression of both enzymes, suggesting that EDSW suppresses AMPK and ACC activities, leading to the suppression of intracellular triglyceride biosynthesis.

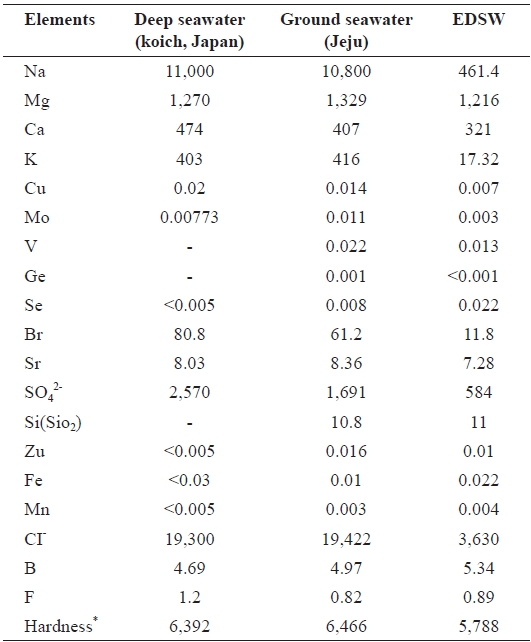

We investigated whether the effect of EDSW on fat accu-mulation might also occur in the liver of experimental ani-mals. ICR mice were allowed free access to a high-fat diet and 10% (v/v) EDSW or tap water (control) for 15 weeks. The high-fat diet lead to a 13.9% increase in body weight (48.9 ± 5.0 g) compared to that of control mice (42.9 ± 1.3 g) after 15 weeks; this was not significantly reduced by EDSW administration (Fig. 6A). However, hepatic fat accumulation was observed in animals fed a high-fat diet and was suppressed by EDSW admin-istration (Fig. 6B).

EDSW with 12 mS/cm electroconductivity, which was pre-pared by electrodialysis of Jeju ground seawater, lacks mon-ovalent ions (sodium, potassium, and chloride), but contains abundant divalent cations including magnesium and calci-um. The presence of microelements (vanadium and selenium) in EDSW is also of interest due to their rarity in other water resources. Recently, the physiological importance of min-eral components has been stressed for the amelioration of a

number of chronic metabolic diseases, such as hypertension (Rylander and Arnaud, 2004), hyperlipidemia (Chen and Lin, 2000; Schoppen et al., 2005), and diabetes mellitus (Barbagal-lo et al., 2007).

Our data show that EDSW promoted the proliferation of non-cancerous CHO-IR cells, but accelerated apoptotic death of hepatoblastonema HepG2 cells. The reason for this discrep-ancy in modulating cellular viability in different cell types re-mains unclear. Previous studies have focused on the role of di-valent cations, especially Mg2+, as critical cofactors for several enzymes. Although Mg2+ promoted citrus flavone tangeretin-induced inhibition of leukemic HL-60 cell growth with less cytotoxicity to normal lymphocytes (Hirano et al., 1995), little is known regarding the direct inhibition of cell growth by Mg2+. Mg2+ concentration is critical for phosphorylation of the tyrosine kinase of several protein kinases (Barbagallo and Dominguez, 2007). It was notable that 10% EDSW stimulated basal ERK activity, a mitogenic MapK, in L6 muscle cells. However, it failed to stimulate the basal activity of PKB/Akt, but augmented insulin-stimulation of PKB/Akt. These results suggest that the abundant Mg2+ in EDSW stimulates the in-trinsic mitogenic enzyme, ERK, thereby promoting CHO-IR cell proliferation. Failure to stimulate the basal activity of PKB/Akt may explain why Mg2+ has a limited role in phos-phorylating tyrosine residues of insulin receptors, but has an important role in maintaining their tyrosine phosphorylation status. EDSW increased both basal- and insulin-induced glu-cose consumption of L6 muscle cells. Insulin-induced glucose uptake in muscle is dependent on the localization of Glut4 from the cytosol to the plasma membrane (Antonescu et al., 2009). Thus, stimulation of basal glucose consumption by EDSW suggests that insulin/Glut4-independent pathways are activated by EDSW. Muscle contraction also stimulates glu-cose uptake independent of insulin receptors through AMPK ac-tivation and Glut4 translocation (Santos et al., 2008). In the present study, EDSW stimulated phosphorylation of AMPK and ACC in HepG2 cells. It is likely that insulin-independent glucose consumption by EDSW might arise from AMPK activation and subsequent Glut4 translocation. The additive in-crease in glucose uptake by insulin and EDSW supports such a possibility. The precise mechanism underlying these effects will be investigated further.

Divalent cations stabilize yeast ADH (De Bolle et al., 1997), and removal of magnesium inactivates ADH complete-ly (Niefind et al., 2003). The binding affinity of

Pharmacological activities of deep-sea water have been reported in hyperlipemia (Yoshioka et al., 2003), atheroscle-rosis (Miyamura et al., 2004), cardiovascular hemodynamics (Katsuda et al., 2008), and fibrinolytic activity (Ueshima et al., 2003). The present study determined a role for EDSW on non-alcoholic hepatic steatosis, a feature of metabolic syn-drome. Incubation of HepG2 cells with 0.5 mM palmitate induced intracellular fat accumulation within 24 h. Exposure to palmitate over 24 h lead to cell death, due to palmitate-induced lipotoxicity. However, addition of EDSW (10%) to the medium prevented excess cytoplasmic fat accumulation for 24 h. Western blot analyses showed that AMPK and ACC phosphorylation were blocked by palmitate, but restored by EDSW, suggesting a beneficial effect of EDSW in the control of hepatic steatosis. In order to support this notion, the effect of EDSW on hepatic steatosis was examined in a high-fat diet mouse model. A high-fat diet increased body weight, but free access to EDSW for 15 weeks inhibited this effect, although not significantly. As shown in HepG2 cells, EDSW reduced hepatic intracellular fat accumulation.

An association between mortality from ischemic heart dis-ease and drinking water characteristics was first shown in Ja-pan (Kobayashi, 1957). Since then, it has been suggested that a number of diseases are related to a lack of essential minerals, especially cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Reductions in the global water supply as well as the severe contamina-tion of water resources threaten human health. Oceanic deep-seawater or ground seawater has been shown to be clean, min-eral-rich, and safe. After previous reports on deep-sea water and the physiological roles of minerals, this study developed a new water resource, ground seawater in Jeju, Korea, and in-vestigated the physiological effects of EDSW. EDSW showed a number of beneficial activities in glucose, lipid, and ethanol metabolism. Although the exact mechanisms underlying these effects remain to be elucidated, some mineral ingredients, par-ticularly the abundant Mg2+ in EDSW, may play crucial roles in such health-promoting effects.