The diffraction grating consists of many grooves that are regularly spaced on a substrate surface. The spatial period of the groove lines typically ranges from one to several wavelengths of incident light. The wavefront of incident light falling on a grating surface is divided into many pieces, one at each groove line. The outgoing wavefront in a particular direction after the diffraction is composed of many interfering components from each groove line. Consequently,the direction in which all components are in phase is highly dependent on the wavelength of the incident light.In the years since its utility in the dispersion of multi-wavelength-component light was identified, it has been widely used for spectroscopy [1]. A tremendous number of spectroscopic applications are based upon grating-equipped spectrometers,including Raman scattering studies of molecular vibrational modes [2-4], fluorescent emission measurements of biological and chemical samples [5, 6], and optical spectrum analysis of photonics devices [7]. More recently,the diffraction grating has been found to be useful in the application of short laser pulse manipulation [8]. In this application, a multi-frequency-component short pulse laser beam is dispersed by a grating and focused on the Fourier plane, where each frequency component is controlled by a spatial light modulator to produce a variety of different shapes of laser pulses from the initial pulse after recombination through a second grating. This grating-based pulse manipulation has been widely adopted in chirped pulse amplifications to achieve high peak intensity laser beams[9, 10].

The spectral resolution of the diffraction grating is limited by the number of grooves that are covered by the incident beam [11], which is analogous to the diffraction-limited spatial resolution governed by the numerical aperture of the objective lens in optical imaging systems . Therefore,to achieve a high resolution, gratings are required to either be of a very large size or to have a high groove density.However, the high-precision ruling process can make this a difficult task. In this study, intrigued by the translational symmetry that is intrinsically imposed on the diffraction grating, we exploit the symmetry and present a very simple method to exhibit unprecedented spectral resolution with a limited groove number.

II . SYMMETRY OF DIFFRACTED FIELDS AND A PLANE-PARALLEL MIRROR PAIR AS A FIELD TRANSLATOR

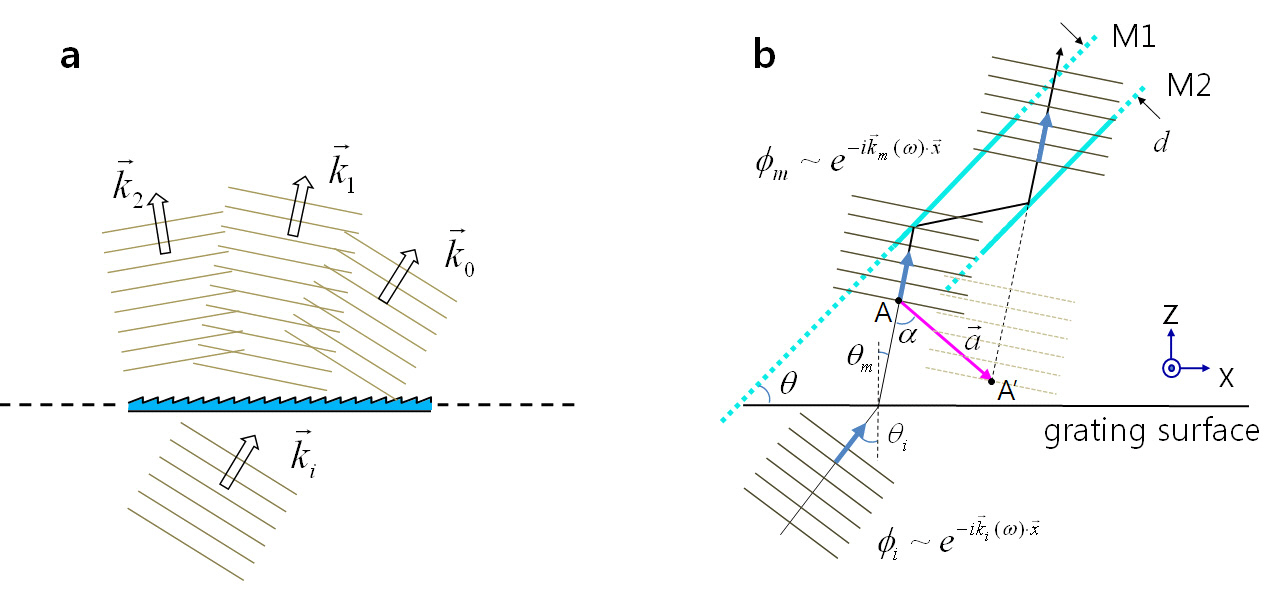

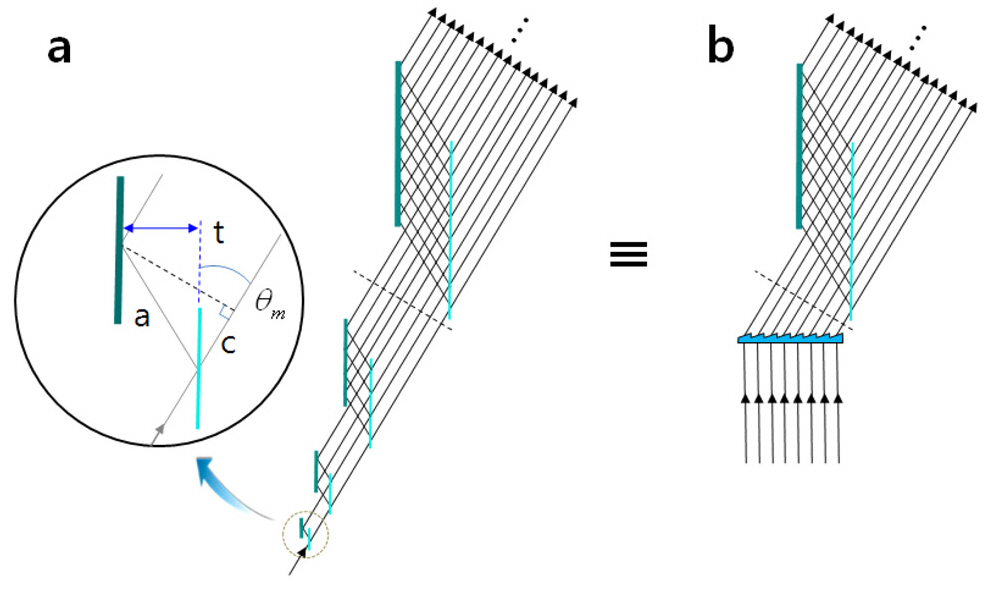

To exploit the intrinsic translational symmetry of diffraction gratings, we first want to have a close look into the field structure around a grating that is illuminated by a plane wave of wavelength λ. As the grating itself and the incident field are translationally invariant upon a x-directed movement,as depicted in Fig. 1(a), the diffracted fields above the grating surface that consist of many diffraction orders have translational symmetries along the x-direction. Throughout the discussions following, we choose a transmission grating and scalar fields for the sake of convenience. Provided that the m-th order diffracted field ?m(□) is a solution to the Helmholtz equation (∇2+k2)?m = 0 with appropriate boundary conditions, the field translated in space by

is also a solution because of the invariance of the equation under the translational operation; that is,

The plane wave solution ?(□) around the grating can be expressed below and above the grating as

where □i is the wavevector of the incident field below the grating, □m is that of the m-th order diffracted field above the grating, and

If we apply the translation operator

to the fields, then

transforms to exp

where □ is a displacement vector. Generally, the field translation is accompanied by the phase shifts of wave functions.To realize the translational operation on the fields, we now consider an imaginary two-mirror element that has two large plane-parallel mirrors that are separated by a certain distance

Thus, any point in the fields is shifted in space by twice the mirror separation, ?□?=2

everywhere in the space.For this condition, we should satisfy the following relations from Fig. 1(b):

where

separation, and

III. BEYOND THE LIMIT ON THE SPECTRAL RESOLUTION OF DIFFRACTION GRATINGS

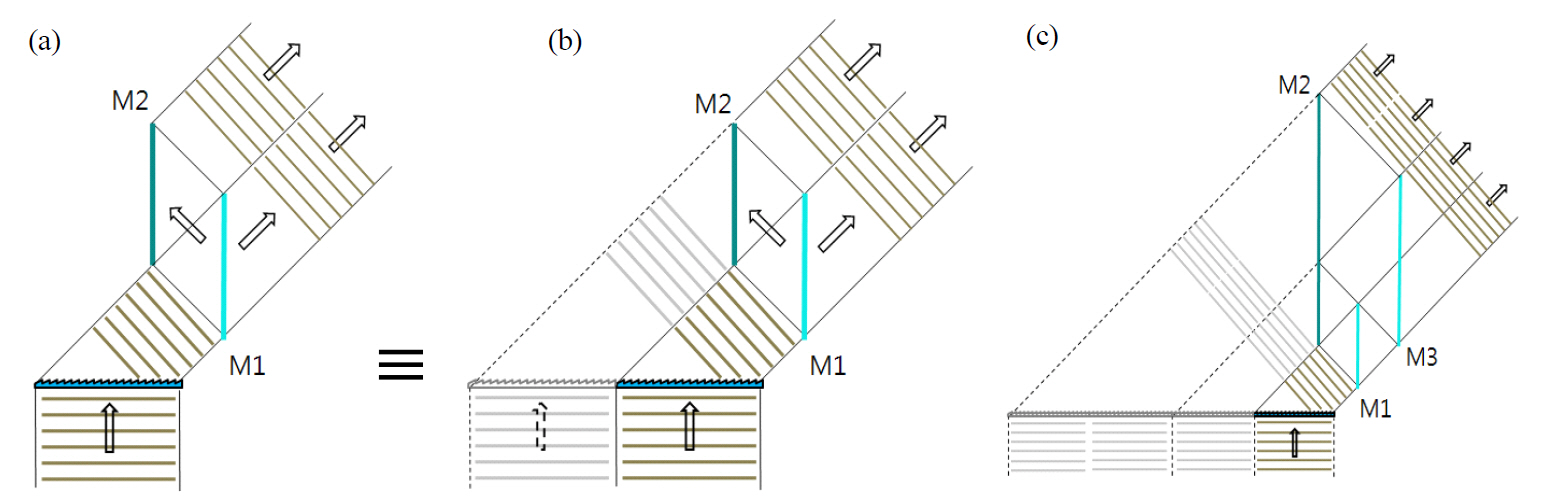

To exploit the symmetry nature of the fields that are formed around a grating system, we propose an optical configuration,as shown in Fig. 2(a), where a plane wave of wavelength λ is incident on a grating plane and diffracted. We restrict the discussion to m = -1. The optical setup simply consists of one full mirror M2 and one half mirror M1 (50%reflectivity) which are parallel to each other and separated by

of the diffracted beam transmits through the half mirror.The other half is reflected toward the full mirror and is reflected again from the full mirror to become parallel to the transmitted beam. Consequently, the second half of the diffracted beam is the field translated by the mirror pair,which has the same phase and intensity as the first half.Therefore, the corresponding equivalent grating system can be depicted as shown in Fig. 2(b). The system works in a manner such that half of the original field and the other half of the field that is translated by 2d interact to provide a larger aperture grating system. This system effectively doubles the number of grooves that are covered by the incident beam. The two-mirror configuration can be repeated once more by adding one more full-half mirror combination,and it consequently enhances the spectral resolution to quadruple that of the original diffraction grating. This concept is illustrated in Fig. 2(c), where the size of half mirror M3 is two times larger than that of mirror M1, and mirror M2 is extended to cover the reflected beam from M3. Additionally,the mirror separation between M2 and M3 is twice as large as that between M1 and M2. In principle, the spectral resolution can be enhanced indefinitely by repeating the full-half mirror combinations.

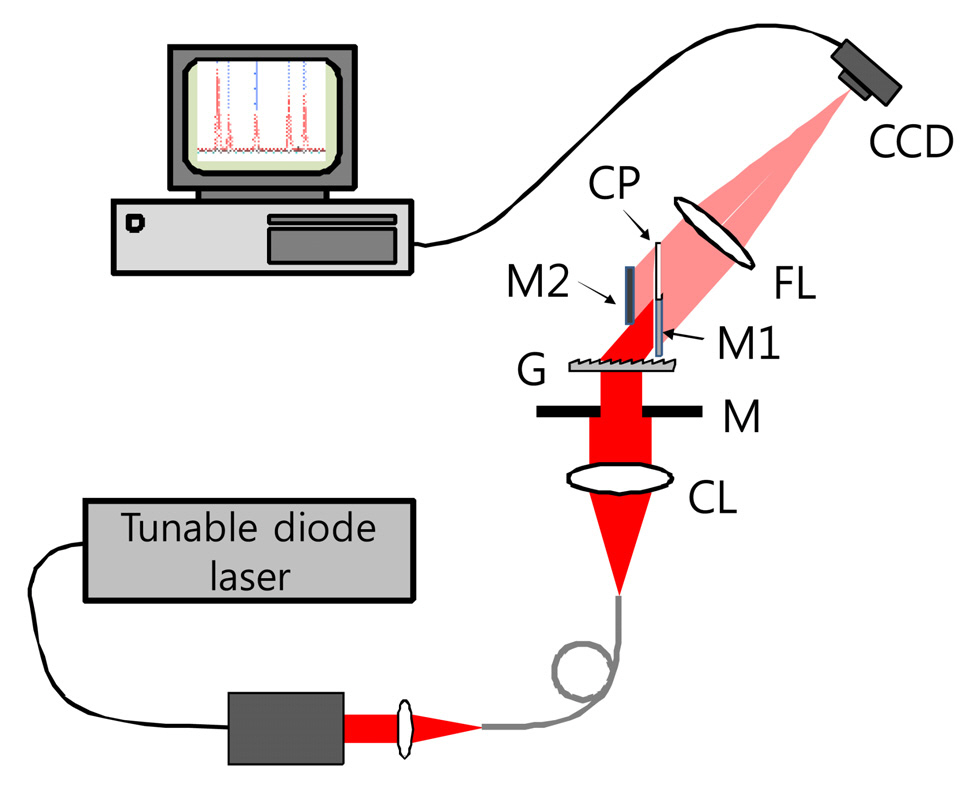

For an experimental demonstration of the enhanced spectral resolution, an approximately 7 mm long and 5 mm wide rectangular-shaped aperture was placed onto a large diffraction grating of 1000 grooves/mm to simulate a grating of size 7 mm × 5 mm. The schematic of experimental setup is shown in Fig. 3. As a light source, a tunable diode laser operating around 773 nm with a linewidth of less than 300 kHz was coupled to a single mode fiber of NA0.12. The diverging laser beam from the output end of the fiber was collimated to make the beam size about 10 mm which was large enough to cover the entire area of the grating surface.The beam was made to strike the grating surface at a normal incidence, as in Fig. 2. Therefore, there were approximately

mately 7000 grooves that were covered by the laser beam, meaning that the first order spectral linewidth

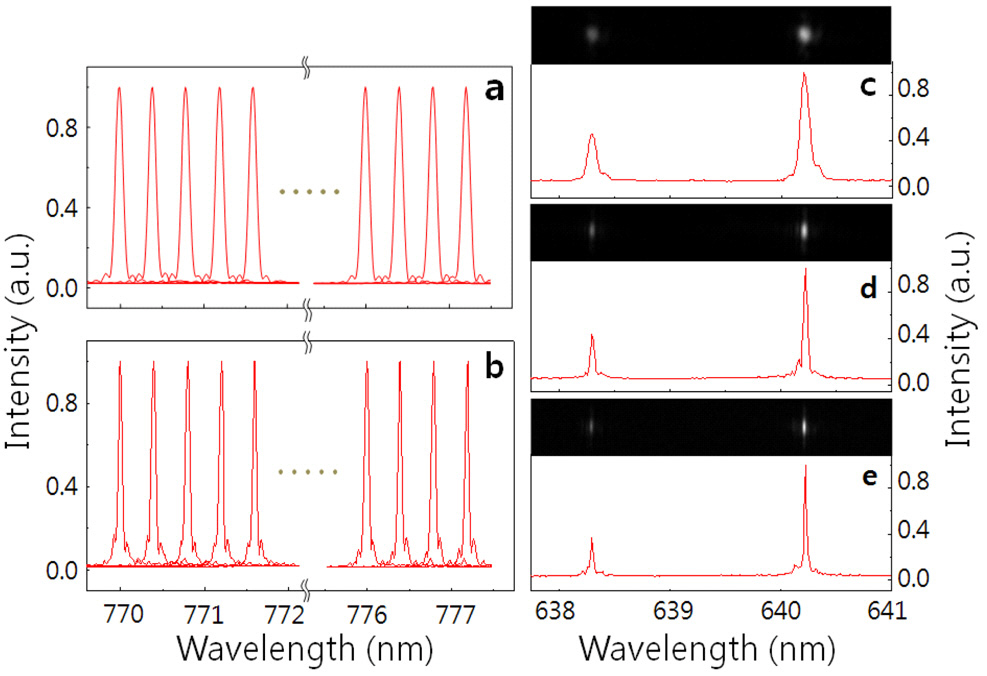

In Fig. 4, we also present the neon emission spectra that were measured in our experiment. Due to the limited size of the CCD detection area, only two spectral lines out of many emission lines from a neon lamp are presented. One is positioned at 638.299 nm, and the other brighter line is at 640.225 nm. Fig. 4(c) corresponds to the neon spectrum that was obtained with the bare grating only, Fig. 4(d) to

a single mirror pair with the grating, and Fig. 4(e) to double mirror pairs with the grating as depicted in Fig. 2(c).Since the relative phase between four diffracted beams is precisely adjusted, more careful alignment is necessary for the double mirror pair case. The spectral linewidths of the 640.225 nm emission for all three cases were measured as 0.095 nm, 0.049 nm, and 0.025 nm, respectively. Above each spectrum are the diffracted emission line spots that were imaged on the CCD detector. It should be noticed that along the dispersion direction the two emission spots become narrower as an additional mirror pair is added.

From the experimental results presented so far, we found that the proposed method works well for a fairly broad range of wavelength even though the working concept is depicted only for a single wavelength in Fig. 2. It can be attributed to the following reason. In the setup, we put the half mirror as close to the grating as possible, which is less than 15 mm. Considering the dispersion of the grating 0.0015rad/nm at 773 nm, the swing angle for 7 nm wavelength change is just 0.0105 radians amounting to 0.16 mm transversal shift at the mirror. It is quite small compared to the diffracted beam width 4.6 mm and does not affect the spectral width so much. However, for a large change of wavelength, the mirror pair has to be moved vertically to be aligned for the new diffraction angle. Now we want to comment on the mirror misalignment effect on the phase mismatching. The most important part is to align the mirror pair at 90 degrees to the grating surface. If the angle is deviated from 90 degrees, then the relative phase of the two beams varies rapidly with wavelength. A simple calculation using Eq. (3) suggests that to keep the relative phase less than one quarter of

IV. OPERATION PRINCIPLE IN THE GEOMETRICAL OPTICS POINT OF VIEW

Next, we want to look at the diffraction system from a different perspective in which the light field is represented by optical rays. This would allow us to see how the multiple two-mirror pairs in a grating system work from a geometrical optics point of view. Let’s consider the interesting optical configuration depicted in Fig. 5, which exhibits scale symmetry. Thick lines represent full mirrors and thin lines represent half mirrors. Along the light propagation direction,the mirror pair scales double in mirror size and separation,and the number of rays is also doubled accordingly. At the smallest unit enlarged in a circle, the mirror pair splits a ray into two rays, between which the optical path difference is represented by

diffraction angle of a specific wavelength

where

For the case of non-zero incident angle upon a diffraction grating, we do not have solutions that satisfy Eq. (3) for the entire wavelength range. Instead, there is a small range, Δλ , around a specific wavelength λ0 over which the equation is satisfied. This case would be important from a practical point of view because diffraction gratings in most spectrometers are generally used in non-zero incident angles. This case will be addressed in detail in future work.

In conclusion, exploiting the translational symmetry of the diffraction gratings, we have found a way to enhance the spectral resolution beyond the limit that is set by the number of grooves covered by an incident beam. A combination of full and half mirrors that are parallel to each other can optically replicate the original grating and place a virtual grating beside it, which effectively doubles the size of the grating, resulting in the resolution enhancement. This twomirror operation can be continued indefinitely for further enhancements by adding more full-half mirror combinations despite the increased complexity and difficulty of experimental implementation. Experimental demonstrations with a narrow band tunable diode laser and a neon fluorescence lamp were provided to show its promising utilities in spectroscopy applications. We have also presented an explanation of the two-mirror operation principle from the geometrical optics point of view, and an illustration with an interesting optical configuration that has scale symmetry was provided.Even though there are some drawbacks of our method such as the limitation of the working spectral range, it can be easily applied to any grating-based spectrometer due to its simplicity. As an example, bulky spectrometer systems in which most internal parts are simply empty space can be made smaller and more compact without degrading the spectral resolution. Since the present study can be applied only to the zero-incident angle, the future study will include the oblique incident angle case for more practical applications.