This study aims to reconstruct the generalization process of the translated word minjujuui 民主主義 to better understand the conceptual history of democracy in Korea. As a means to this end, we must first ask whether the golden standard for research on conceptual history, set by the Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe (G.G., Basic Concepts in History: Historical Dictionary of Political and Social Language in Germany), applies to the Korean context. The G.G., a monumental study in the field, tracked the semantic histories of the basic concepts that constitute modern society, among which “democracy” is indispensable. In order to write democracy’s conceptual history, the authors traced the processes of “Verzeitlichung” (temporalization), “Ideologisirung” (ideologicalization), “Politisierung” (politicization), and “Demokrasierung” (democratization) that the concept of democracy underwent during a Sattelzeit (saddle period), thus declaring in its concluding remarks that democracy in mid-twentieth-century Western society had become All-Begriff (a universal concept) that anyone could use for their own clashing purposes (Brunner et al. 198). If so, is the same true of Korea—a non-Western society that underwent a dissimilar modernization process? How has democracy become one of the most prominent basic concepts representing modern Korea? What are the distinctive characteristics of the generalization process of democracy in Korea?

More than two decades have elapsed since the first studies on Korean conceptual history inspired a steady flow of quality research. Strangely enough, however, this scholarly interest has eluded the crucial historical process by which the imported concept of democracy arose as a basic concept marked by the four characteristics mentioned above (Na 2014, 97). Although numerous studies on modern Korean democracy have been published, most have analyzed it at the levels of political thought or political discourse.1 To fill this scholarly lacuna, our study directs attention to the historical generalization of minjujuui—the translated word for democracy that is peculiar but hegemonic in its usage in Korea and East Asia. In our research, the term “generalization” denotes two interconnected phenomena: First, the standardization of minjujuui as the translated word for democracy, and second, its popularization among the general public. Thus, our study investigates how this translated word for a foreign concept entered common usage and how it became the standard word for democracy—not two disparate events but two phenomena or processes tied together by their co-occurrence and mutual causation.

This process of standardization and popularization was not dealt with in the G.G. because it is specific to non-Western societies in which a word for democracy had to be newly introduced. In Western societies, the concept of democracy and the word to identify it has existed since the classical era. Hence, it seems sufficient to analyze in what contexts and through what processes the concept of democracy has expanded its meaning from the specific type of polity to the constituent principle of society to delineate its conceptual history. In contrast, the process of generalizing the translated word for democracy in non-Western societies such as Korea needs to be further reviewed because this concept is tied to a word (Olsen 2012, 172). In the early phase of Korea’s reception of democracy, several Korean translations for this Western concept were devised, and each competed for official status as the standard translated term for general public usage. This generalization process preceded the democratization (Demokrasierung) of the imported concept of democracy. In other words, for democracy to take root as a popular concept in Korea, the generalization of the translated term for it needed to be achieved in advance. Thus, this article examines the generalization process of the translated term minjujuui, mainly focusing on the timeline and manner by which it occurred.

To this end, we adopt both quantitative and qualitative approaches. The generalization process consists of two aspects: popularization and standardization. The completion of the former signifies that minjujuui has entered the mainstream language of the political community, while the latter indicates that members of the said political community also confirm the term as the standard translation for democracy. To examine the popularization process, we analyze the frequency with which the word minjujuui was used based on data derived from crawling Korean newspapers and magazines, on the assumption that more frequent use of the term minjujuui in popular print media indicates the term has become more popularized among Koreans in general. We also examine a series of bilingual dictionaries published in Korea to trace the standardization process. For the qualitative analysis, we investigate the ideological and political contexts of minjujuui’s popularization and standardization. Since an increase in the use of minjujuui must have been prompted by changes in the ideological and political contexts of the word’s users, our qualitative analysis will identify the contexts that were the driving force behind minjujuui’s popularization.

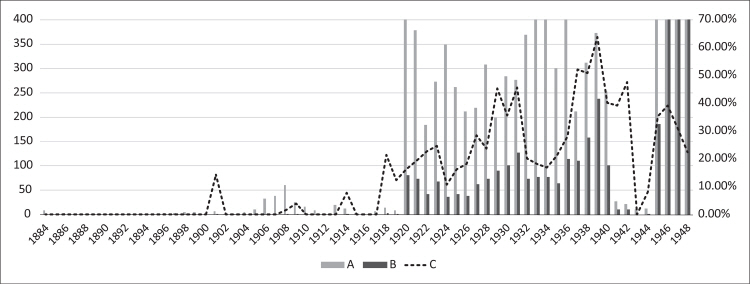

The chronological scope of analysis is from January 8, 1884 to August 15, 1948. The start date for this time frame is set on the year in which the newly translated word minju 民主 first appeared in a Korean newspaper after being translated from English to Chinese and then into Korean. During the early stages of democracy’s reception, various new translated words for democracy were derived from this original term. The endpoint of the research was also based on a preliminary analysis of the frequency of minjujuui’s use. Therefore, we first investigated the frequency with which the word minjujuui appeared in print from a total of 26,259 articles in Korean newspapers and magazines that include the word minju.2 The chart below represents the findings of our analysis in time series.

Figure 1 shows that the use of the word minjujuui increased exponentially during the founding of a democratic South Korea immediately after independence, thus suggesting that the word minjujuui was widely used and recognized around this period. Based on this finding, we limit our research scope of the generalization process of minjujuui to the period between January 8, 1884 and August 15, 1948, i.e., the foundation date of the Republic of Korea. Also, given the fluctuation in frequency trends, it is possible to assume that the generalization process of minjujuui consists of four critical periods: during these periods, the use of minjujuui increased significantly. Therefore, we will focus on the four periods that figured so prominently in the generalization process, attempting to place each period in its proper ideological and political contexts.

Based on this preliminary analysis, this article is organized as follows. First, to understand the background of the use of the term minjujuui as the translated equivalent of “democracy,” we briefly examine early translations of “democracy” from the late 19th century to the 1910s in Section 2. We then examine four periods in which the use of minjujuui notably increased: the early 1920s in Section 3, the late 1920s to the early 1930s in Section 4, the mid-to-late 1930s in Section 5, and the United States Military Government period in Section 6.

According to our quantitative analysis, the term minjujuui did not feature in Korean media until 1900, whereas the word minju figured in Korean newspapers decades before this, i.e., from the earliest phase of democracy’s transplant into the Korean context. In this initial stage, the concept of democracy was translated in various ways, and minju was only one of these early translations. However, in contrast to the present common meaning of the term, the word originally originated as a Chinese translation of the English word “republic” and not “democracy” (Song and Kim 2021, 9-10; Chen 2011, 12-14). Subsequently, Korean literati, heavily influenced by Chinese cultural clout, uncritically embraced this translated term in the early 1880s.

In Korean media, the translated word minju first appeared in the Hanseong sunbo in 1884.3 In the KNA database for the Hanseong sunbo, there are nine articles in which minju was used in three variations (minjujiguk, minjuguk, and minju) to introduce Western political affairs. However, given the context in which these expressions were used, it is possible to ascertain that they correspond to “republic,” not “democracy.”4 This translation practice continued in the Hanseong jubo, which succeeded the Hanseong sunbo.5 Many articles in both the Hanseong sunbo and Hanseong jubo were translated reprints of Chinese newspaper articles from Shanghai or Hong Kong, so it seems that in this reproduction process the Chinese translation of “republic” as mínzhu 民主 was uncritically accommodated in Joseon Korea as minju in the 1880s.6

During the late 1890s, minju emerged in the Dongnip sinmun as the translated term for “democracy” instead of “republic.” This new usage of minju seems to be indebted to the cultural influence of Japanese translation practices.7 However, of the 13 total mentions of minju in this newspaper, 12 were still used to indicate “republic,” and only one corresponded with the word “democracy.”8 Therefore, it is fair to say that until the end of the 1890s, minju was used primarily to translate the word “republic,” in line with Chinese translation practices. However, this situation began to gradually change in 1905, as can be identified in the Hwangseong sinmun. In this newspaper, we found the word minju in 52 articles, of which 32 were judged to be the equivalent of “democracy,” and 31 of these 32 were published after 1906.9 This fact suggests that, as of 1906, minju was more frequently used to translate “democracy” than “republic.”

The critical historical contexts to this shift in usage were the increased Japanese influence over Korea and the top-down political reform in imperial Russia that followed the First Russian Revolution. Japan’s cultural sway grew even more potent in Korea with the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War and the subsequent conclusion of the Protectorate Treaty of 1905 between Korea and Japan. Under such changed circumstances, news about Russian politics in the post-Revolution era became a catalyst for the frequent use of minju as the translation for “democracy.” While delivering news from Russia via a foreign news agency, the Hwangseong sinmun consistently referred to the Russian “democratic party” as minjudang following the Japanese translation practice. All 31 references to minju in the Hwangseong sinmun starting from 1906 fall under this category.

Furthermore, this phenomenon was not limited to the Hwangseong sinmun. According to our statistical analysis, the expression minjudang appeared with increased frequency in every Korean media from 1906, suggesting that the new translation practice resonated with other contemporary newspapers and magazines. The usage of minjudang as a translation of “democratic party” continued into the 1910s after the Japanese annexation of the Korean Peninsula. In the Maeil sinbo, the only Korean-language newspaper in the 1910s, we identified 82 articles from 1910 to 1919 that included the expression minju. The most significant number of articles were written in 1913 when all expressions with minju were references to minjudang. This practice of translating a democratic party as minjudang played a pivotal role in phasing out the late 19th-century Chinese translation practice of using minju to mean “republic.”

Though minju shifted from being the translation for republic to that for democracy at the beginning of the 20th century, this did not coincide with the widespread use of minjujuui as the translated word for democracy. The term minjujuui had begun to circulate in early 20th-century Korea under deepening Japanese influence, but the frequency of its use was negligible throughout the 1900s, with only two articles including minjujuui being found in Korean newspapers and magazines of the period.10 According to our analysis, this trend continued into the 1910s—the word minju was used in only 76 articles between 1911 and 1919; minjujuui was limited to only five cases.11

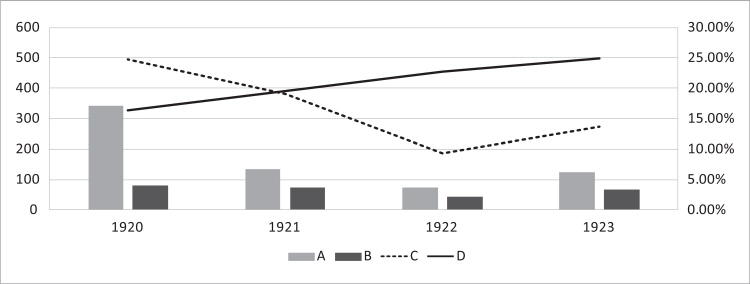

By the 1920s, there was a dramatic change in the frequency of minjujuui’s use, as visually represented in Figure 2. In the 1920s, the total number of articles including minju amounted to 495 articles—81 of these included minjujuui. This seems to be a sudden increase of frequency in the use of both minju and minjujuui, given that the number of articles including minju and minjujuui in 1919 was only eight and one, respectively. While the number of articles including minjujuui decreased slightly from 1921 to 1922, the general tendency indicates an upward trend with the proportion of articles referring to minjujuui to all articles that included minju steadily rising each year from 16.36 percent in 1920 to 24.82 percent in 1924.

This rapid spike in the usage of minjujuui can be attributed to the popular use of minshushugi 民主主義 in Japan that was provoked by World War I and its subsequent diffusion into colonial Korea following a reluctant change of Japanese colonial policy in 1920. During World War I, the Entente Powers framed their war against Germany as democracy’s valiant fight against militarism (Siracusa 1998, 3). British society in particular advanced this ideological purpose with great persistence from the onset of the war. British newspapers drummed for Britain’s struggle against Germany, portraying it as the conflict between two fundamentally competing forms of political organization.12 According to this popular opinion, democracy was not only a specific form of government but also an ideologicalized construct that embodied a particular type of civilization.13 This public opinion about democracy that began in Britain gained greater mileage as American forces joined the war. In his 1917 State of the Union Address, Woodrow Wilson declared Allied effort to make the world “safe for democracy,”14 which gave strength to the Allies’ attempts to shape the ideological nature of the war as a defense of democracy.

In contrast, imperial Japan had firmly repudiated democracy internally. But she swiftly declared war on Germany from the early stages of World War I in consideration of its national interests. Japan’s entry into the war unexpectedly sparked domestic public demands for democracy in tandem with the widespread fervor for democracy that swept its wartime allies Britain and the United States. According to John Dewey, during his 1919 visit to Japan, the political atmosphere had changed, with even manual workers and rickshaw men expressing their opinions on democracy in the streets (Dewey 2008, 156). Such a burst of public interest in democracy naturally led to the explosive use of the translated word minshushugi in Japanese popular media. In short, the word and concept of minshushugi became considerably popularized in Taisho Japan during this time (Song and Kim 2021, 23).

This popularity, however, did not immediately spread to colonial Korea due to Japanese restrictions on freedom of the press there.15 Japanese suppression of Korean political expression was so severe that the Japanese Government-General of Korea did not issue a single license for Korean-owned newspapers until the March First Movement in 1919 (Jung 1978, 243-244). Due to such restrictions on a free press, colonial Korea initially remained immune from the feverish spread of democratic ideas and values that swept the Entente Powers. However, as Japan reluctantly adopted a conciliatory policy after the March First Movement, freedom of the press was allowed, albeit with limitations.16 Indebted to this propitious circumstance, the public passion for democracy and the concomitant popularity of minshushugi in Japan swiftly transferred to colonial Korea.

Under these new circumstances, minjujuui (the Korean equivalent of minshushugi) was easily picked up by Korean intellectuals. However, we need to be careful not to jump to the hasty conclusion that their use of minjujuui was simply a reflex of the popularity of minshushugi in Japan. Instead, it must be seen as the fruit of their active endeavors to receive and internalize the idea of democracy. The concept of democracy was still an obscure and remote one in colonial Korea in the 1910s, regardless of whatever translated term was used in the print media. However, Korean students studying in the cosmopolitan center of Japan were surrounded by the idea of democracy and determined to introduce it to their Korean homeland. In the latter half of the 1910s, these students formed a cohort group roughly 700 strong bound by their shared hopes for the post-war fate of colonial Korea. These new Korean elites were conscious of their national responsibility to save Korea from its tragic colonial status. They saw grounds for new hope in the face of the seemingly rapidly changing world order prompted by WW I. In this awakening, they naturally came close to the Japanese Taisho democracy movement, which upheld democracy as the symbol and promise of a coming new world order. Korean elites did not limit themselves to passively assimilating the movement’s ideas, but actively engaged in the Movement itself (Lee 2017, 72-74).

In their active involvement in the Taisho democracy movement, the Korean students in Japan found new prospects for overcoming the reality of colonial Korea in the much-touted concept of democracy. Many of them returned to Korea with this expectation and joined the ranks of Korean newspapers. The Dong-A Ilbo is a representative case because all its major writers and staff—editor-in-chief Chang Deok-soo, members of the editorial board such as Lee Sang-hyup, Jang Deok-jun, Jin Hak-mun, and Park Il-byeong, and the owner of newspaper Song Jin-woo—had studied in Japan as members of the cohort mentioned above (Lee 2017, 78). As was the case with the Dong-A Ilbo, a new generation of Japan-educated Korean intellectuals pegged their hopes for their nation’s future on democracy, and this expectation led to their frequent and fervent invocation of minjujuui in colonial Korea.

In the early 1920s, minjujuui was, being used to denote “democracy,” had yet to become the standard translation word for “democracy.” It was even further removed from entering the everyday language. The use of minjujuui in newspapers and magazines slightly decreased from 1923,17 and it was not used in contemporary dictionaries.18 However, the number of articles including minjujuui steadily increased from 1927 to 1931 and numbered 63, 73, 90, 102, and 127 respectively for each year. Furthermore, the proportion of articles with minjujuui among the articles that include minju almost doubled between 1927 and 1931.19

This increase in the use of minjujuui in the late 1920s can be attributed to the worldwide spread of communism during the first half of the 1920s. According to Marxist-Leninism, the mainstream form of communism in the 20th century, democracy was a means of proletariat domination and a prerequisite to arriving at the final stage of communist society (Lenin 1964, 457-461). With this new perspective, communists militantly engaged in the semantic struggle over democracy in which various other political forces defended democracy as defined from their respective viewpoints.20 This battle over the meaning of democracy spread to the Far East as Soviet leaders turned their eyes to Asia (Service 2007, 115; S. Kim 2019, 350). The ideas of revolutionary international Marxism deeply resonated with the socialist group that had formed in Korea around 1919, which then proceeded to actively organize domestic mass movements from 1920 (J. Park 2008, 80).21 Along with the nationalist movement, these socialist movements formed one of the two central pillars of mass movements in Korea and played a crucial role in increasing the use of minjujuui starting from 1927, as illustrated in Table 1.

The above table suggests that the increased use of minjujuui dating from 1927 was associated with a simultaneous increase in the number of articles related to communism or socialism.22 This implies that minjujuui was primarily associated with the mid-1920s communist and socialist movements. However, one peculiar aspect is that the Korean socialist movement was already actively underway by the early 1920s. In contrast, minjujuui began to be used frequently in this context only after the mid-1920s, so there is a conspicuous time lag between the event and the invocation of minjujuui in its context. Why was the term minjujuui brought forth with such frequency in this context from the mid-1920s, rather than from the early 1920s? The following four factors may account for this gap.

First, the sudden increase in references to minjujuui can be explained in part by the debate between the “ML” and “Seoul” Korean socialist factions over the issue of the “National Cooperation Front,” a revolutionary strategy advocated by the ML faction that was based on an understanding of the Korean revolution as a stage of bourgeois-democratic revolution (Jun 1998, 114; I. Kim 2004, 392). This consequential debate was conducted in newspapers, and thus minjujuui was also frequently mentioned in the same pages. Second, Korean socialists actively devoted themselves to organizing various public associations during this period, and in this process, they adopted minjujuui-jeok jungang jipgwonje (democratic centralism) as their operational rule for associations (J. Kim and C. Kim 1986, 114). In the newspapers, the word minjujuui was repeated with great frequency to introduce their organizing activities.

Third, the surge in references to minjujuui also reflects the Korean public’s interest in the political activities of Japan’s socialist movements. In 1928, Japan conducted the first election following its General Election Law (1925) that had introduced universal male suffrage. Japanese socialists participated in this electoral process, actively vying for seats in the House of Representatives (Masumi 1988, 138-139). Korean newspapers such as the Chosun Ilbo and Dong-A Ilbo, delivering news about these exciting new political developments, employed terms such as “sahoe minjujuui” (social democracy) or “bureujoa minjujuui” (bourgeois democracy) commonly mentioned by Japanese socialists in their speeches. Fourth, yet another factor was the socialist literary and art movement that sought to employ the arts to revolutionary ends. The Korea Artista Proleta Federatio (KAPF) was organized in late 1925 and attempted to promote socialist culture to a popular audience from the late 1920s (Choi 2014, 202). To this end, its members often contributed to newspapers as a part of their promotional endeavors. While doing this, they frequently used the word minjujuui in their submissions.

The second popular spread of minjujuui also influenced the translation practice, as can be seen in the 3rd edition of James Scarth Gale’s The Unabridged Korean-English Dictionary (韓英大字典) published in 1932. Gale added more than 35,000 new words in these dictionaries, reflecting timely updates in modern words and their contemporary usage in Korea (Gale 2012, 18-19). According to our research, this dictionary was the first to introduce minjujuui as a Korean word for “democracy.” Although this entry represents a significant development in the generalization of minjujuui, this single dictionary entry alone certainly cannot attest to the complete popularization or standardization of the term. Even Gale’s dictionary included minju and minju jungche—alternative expressions that had been commonly used as translations for democracy. A similar word, minjujiguk, was even listed as the Korean counterpart for “republic,” thus indicating that the original Chinese translation still exerted semantic influence. Furthermore, the frequency with which the word minjujuui appeared in print media decreased from 124 to 74 articles between 1931 and 1932, a trend that lasted until 1935.23

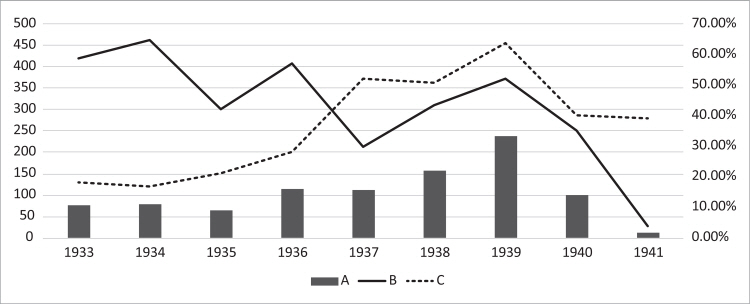

This short downward trend in the use of minjujuui changed suddenly in 1936 (Fig. 3). The number of articles including minjujuui was only 64 in 1935, but this figure almost doubled in 1936, when a total of 115 articles featured this word. This upward trend continued until 1939, when we identified 238 cases—this is twice as much as the highest count from the second period of popular spread that coincided with Korea’s socialist movements in the late 1920s. More interestingly, the percentage of occurrence of minjujuui among articles that included minju was more than 50 percent in 1937 and 1938 and then peaked in 1939, when it reached 63.81 percent. Thus, we note that after the downturn in use between 1932 and 1936 came a boom in the use of the term minjujuui.

This third popular spread of minjujuui occurred during a period in which political repression and thought control were strictly enforced in the name of the Kokutai Meicho 國體明徵 (Clarification of the National Polity). In 1935, the Japanese government adopted two declarations to clarify the kokutai (Gordon 2005, 364), and in 1936 the tosei-ha (control faction) in the Imperial Japanese Army later reiterated the importance of the Japanese kokutai and its incompatibility with democracy (Osaka mainichi shimbun, December 5, 1936). In 1937, the Japanese Ministry of Education officialized this position by issuing a statement on the relationship between the kokutai and Western thought, in which it condemned democracy, socialism and communism alike as contrary to the kokutai (Monbushō 1937, 5). However, minjujuui became popular again in colonial Korea despite the Japanese government’s staunch anti-democratic stance. To make sense of this counterintuitive trend, it is necessary to look into the articles published in the two major Korean newspapers (Chosun Ilbo and Dong-A Ilbo) containing the most significant number of articles including minjujuui.

Table 2 shows that articles about Europe, the Americas, and Russia accounted for almost 90 percent of the articles that included minjujuui. This staggering proportion suggests that foreign news was the primary driving force behind this third popular spread of minjujuui. The underlying cause of this burst of foreign news was the escalation of the global political and ideological confrontation between democracy and fascism. In 1936, the Spanish Civil War broke out as reactionaries launched a coup d’état against the country’s Popular Front government, which quickly led to fatal ramifications at the international level. Moreover, Germany, which had concluded an Anti-Comintern Pact with Italy, persisted in its expansion to unite the German nation and thus triggered World War II. Ideological confrontation over democracy also intensified during this escalation of political conflict. This is because fascist leaders, despite their blatant opposition to Western liberal democracy, nonetheless fancied themselves as vigilant guards of true democracy and actively pushed for recognition as such.24 Thus, the rise of these totalitarian ideologies did not simplify ideological competition into the dichotomous camps of fascism and democracy, but rather intensified and complicated the semantic competition over democracy itself. The third popular use of minjujuui was indebted to this deepening political and ideological confrontation. Newspapers in Korea intently traced the series of turbulent events that culminated in the outbreak of World War II and in the process adopted the expression minjujuui to deliver information regarding growing global confrontation.

This third popular spread of minjujuui marks a critical juncture in the word’s long journey to become the standard translated term for democracy. One way to identify the standard translated word for “democracy,” and thus minjujuui’s status relative to alternative expressions, is to examine the standard Korean translation for “democratic country/democracy.” Although minjujuui was used in the 1920s as established in the preceding paragraphs, it was rarely appended to the letter “country” (guk) to form the amalgam minjujuuiguk to refer to democracy as a polity.25 Rather, the word minjuguk was more frequently called upon for this purpose. However, this trend began to change as minjujuuiguk, an idiosyncratic translation in the 1920s, came to be more widely used than the previous orthodox expression during the peak of minjujuui’s popularization i.e., between 1938 and 1939. This suggests that minjujuui had by then gained the upper hand in the battle to become the standard translation of democracy.26

At this point, we are compelled to adopt a comparative perspective to assess the validity of the conclusions we draw from our data-based analysis. This general trend in the reception and popularization of the translated word for “democracy” was not an exceptional phenomenon limited to colonial Korea. We identified a similar pattern in Japan. According to our analysis of two Japanese Databases—the Kobe University Library Newspaper Clippings Collection and the Japanese National Diet Library Digital Collections—the number of articles and books including minshushugi (democracy) increased significantly from 1936 to 1941.27 It is, however, unsurprising that such a similarity exists between Korea and Japan, given their shared political experiences. For World War II, the outcome of heated global ideological confrontation was a common subject of intense interest for both countries. Thus, it was natural that a significant increase in the use of minjujuui and minshushugi in Korea and Japan, respectively, occurred in similar forms and at similar times.

However, it may be an oversimplification to deem the two phenomena identical, given that the third popular spread of minjujuui in Korea was more than a reaction to global ideological confrontation. Korean media viewed minjujuui from a more positive outlook, as seen in the articles covering the global confrontation between democracy and fascism. For example, in a Chosun Ilbo editorial published on June 6, 1936, the writer predicts that minjujuui will prevail in its mortal combat with fascism because human beings have a strong and innate desire to enjoy fundamental freedoms and rights. The Dong-A Ilbo article entitled “Lack of Awareness of Rights,” published on May 1, 1936, also expressed similar hopes for minjujuui and its promise of human dignity. The fact that all major newspapers in Korea spoke in unison in their hope for democracy during the mid-to-late 1930s proves the unified desire that Korean intellectuals had for democracy, even though these expectations were temporarily abandoned after the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Pacific War.

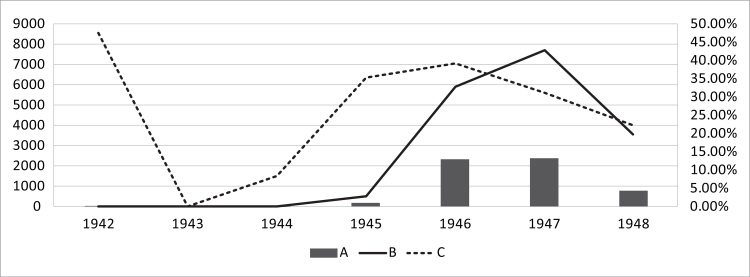

As the Japanese Government-General’s control over Korean media intensified in preparation for all-out war in 1940, freedom of the press was heavily restricted, and the major dailies Chosun Ilbo and Dong-A Ilbo were forced to close. As a result, the number of articles including minju and minjujuui plummeted, as shown in Figure 4. It is no exaggeration to say that minjujuui almost completely disappeared from the pages of the Korean press between 1943 and 1945. There is only one exception to this rule: an article published in the Maeil sinbo (August 6, 1944) mentioned minjujuui, but primarily to criticize American hypocrisy.

However, the use of minjujuui exploded immediately after Japan lost the World War II and its former colonies gained independence. In the first half of 1945 through August 15, there were precisely two articles that even mentioned minju, but this number rapidly increased to 528 between August 15 and December 31, with a total of 187 articles among these explicitly referring to minjujuui. The word minjujuui became daily more popular once newspapers and magazines began to publish again in 1946. In 1946, there were more than 2,300 articles including minjujuui, almost ten times the number of 1938—the peak year of the third period of popularization.

This fourth popular spread of minjujuui resulted from the happy marriage of the American policy of Korean democratization and the Korean people’s own passionate desire for the long-awaited promise of democracy. First, the US military government championed and pushed for the democratization of the Korean peninsula—a policy goal that became the trigger for minjujuui’s explosive popular use. Furthermore, as mentioned before, World War II was cast as a confrontation between competing ideologies. Thus, the victory of the Allies and the defeat of Japan could be interpreted as a triumph of none other than democracy itself. In this vein, the US attempted to apply principles of democratic self-government to the reforms in Japan immediately after World War II (Dower 1999, 76-77), and the US military government in Korea similarly presented its goal as the democratization of Korea and the establishment of a stable democratic country, as John Reed Hodge, the American military governor, declared at a press conference (Jayu sinmun, October 10, 1945).

In addition, American government policy, as embodied in the outcome of the Interim Meeting of Foreign Ministers of the United States, United Kingdom, and USSR, was another major factor that enabled minjujuui to emerge as a mainstream catchphrase on the Korean Peninsula. In the communiqué agreed to by the three victorious powers, it was decided to install “a provisional Korean democratic government” in consultation with “the Korean democratic parties and social organizations,” with “a view to the re-establishment of Korea as an independent state, the creation of conditions for developing the country on democratic principles.”28 Given these straightforward guidelines, the American military government instated democratization policies in various fields from the very outset of its interim military rule. In turn, Korean media frequently invoked minjujuui to deliver the latest news about the US military government’s policies and their editorial boards’ opinions on them.29

However, the fourth popular spread of minjujuui cannot be explained by American policy decisions alone. The rivalry between political parties over the course and goals of democratization in Korea also had a decisive influence. In an optimal environment to seek and explore Korean democracy made possible by American policy decisions, domestic political parties tried to funnel the deep desire for democracy simmering in Korean society by rallying around the catchphrase minjujuui. This collective desire for democracy in Korean society was palpable even in the eyes of a foreign correspondent for an American newspaper (Jayu sinmun, November 4, 1945).

The Korean people’s fervent longing for democracy, apparent to anyone who visited the nation, did not arise suddenly after 1945 but had been dormant in Korean society since the mid-to-late 1930s, as mentioned in the previous section. Under colonial rule, minjujuui was invoked to signify the vast array of aspirations held by the suppressed but hopeful Korean people so that the usage of the term was more intense than in Japanese society. Although the Japanese totalitarian government suppressed the expression of these aspirations during World War II, democracy’s defeat of fascism and the concomitant independence of Korea unleashed an outburst of suppressed longing for democracy with the explosive use of minjujuui.30

The term minjujuui became much more than a word, and this new embodiment of the aspirations of the Korean people naturally became the focal point for heated confrontation between political parties on the left and right. The major right-wing political party that came to the defense of minjujuui was the Hanmin Party, which had roots in the Dong-A Ilbo group. Immediately after Korea gained independence, editorial members of the Dong-A Ilbo reaffirmed their endorsement of minjujuui (Dong-A Ilbo December 1, 1945), and the Hanmin Party, in which key figures from the Dong-A Ilbo participated, also advocated the implementation of “political minjujuui” and “economic minjujuui in order to realize democracy’s promise of freedom and equality” (Chosun Ilbo, December 22, 1945).

On the left, the Communist Party portrayed itself as the political force that had shouldered the “struggle for minjujuui-jeok (democratic) freedom and its development” during the colonial period. It advocated for the establishment of “progressive minjujuui” that was understood to be “substantial minjujuui with specific contents to tackle fundamental challenges, such as the rapid improvement of working people’s lives” (Jayu sinmun, October 12, 1945; Dong-A Ilbo, December 2, 1945). In line with the stance and claims of the Communist Party, various other social groups joined forces and also defended the slogan of “progressive minjujuui” (Jayu sinmun, December 14, 1945; Joongang sinmun, January 25, 1945; Chosun Ilbo, January 25, 1946).

On the other hand, a group of moderates endeavored to form a left-right coalition by promoting what they coined “new minjujuui.” One such proponent was Ahn Jae-hong, a center-right figure who published a series of articles titled “New Nationalism and New minjujuui” in the Sinjoseonbo between October 12 (no. 1) and November 14, 1945 (no. 23), arguing for the necessity of a “new minjujuui” to build a “unified nation-state.” Baek Nam-eun, yet another center-left figure, argued further that a “united new minjujuui” was the “right route for establishing a democratic Korea” (Sincheonji, June 1946).

In short, almost every political party advocated the cause of minjujuui and repurposed it toward their ideological demands. They then cast each other as anti-minjujuui, the most damning accusation possible in these heated minjujuui debates. This scramble for minjujuui among the political elite reveals the popularity of the concept of minjujuui among the general public. “Time for minjujuui,” a seemingly odd radio program title, symbolized the status of minjujuui that had finally entered the everyday language of Koreans with broad appeal among all Koreans.31 As the title of the program suggests, all Koreans were living in the time for minjujuui, and in the heat of the moment, their collective concept of democracy gained added measures of diversity and complexity, which became expressed in an equally diverse number of ways. Simultaneously, the word minjujuui entered the colloquial language of everyday Korean (dailyization). Thus, this once word-for-word translation of a Japanese term for a Western concept gained official status as the standard Korean word for the concept of democracy (standardization). In bilingual dictionaries published after the establishment of the Republic of Korea, democracy was almost consistently and uniformly translated as minjujuui.32 Consequently, going through this fourth period of popular use, minjujuui was finally generalized as the translated term that would serve as the bedrock for the concept of democracy in Korea.

To address the crucial questions of how democracy became a basic political concept in Korea and what characterized this process, we examined the generalization process of the word minjujuui because this was a prerequisite for the democratization of the concept of democracy and its eventual realization in political organization and society. As a result of our quantitative and qualitative analysis, we established that minjujuui was already subject to ideologicalization, politicization, and temporalization in its generalization stage. The first popular use of minjujuui was driven by the temporalization of minjujuui, and then it was ideologicalized and politicized in tandem with successive waves of the popular use of minjujuui. These phenomena were even more intense than in the West, from which the concept of democracy originated. One explanation for Korean democracy’s intense conceptual history is the confluence of internal and external factors that drove the generalization process.

The popularization of minjujuui in Korea reflected the global spread of democracy that had already been intensely ideologicalized and politicized in the West. All four periods examined in this article were a reaction to global trends and events—more specifically, the conflict between democracy and militarism during World War I, the spread of communism following the Russian Revolution, and the ideological confrontation between democracy and fascism in the inter-war and World War II periods. In their endeavor to keep abreast with these global ideological currents, Korean newspapers and magazines frequently used minjujuui in their printed pages, which in turn contributed to the generalization process at home.

However, the generalization process of minjujuui was not simply a byproduct of the ideological confrontations that started in the West and spread to East Asia. Desperate to overcome the yoke of Japanese colonial rule, a generation of young Korean intellectuals sought hope and vision for an alternative political future in the concept of democracy. For this reason, the meaning of the word minjujuui came to further embody fervent hopes and expectations for an autonomous Korean future so that the Korean word for democracy came to assume additional layers of meaning more intense than in the West. In other words, the Korean people’s confrontation with the reality of colonial rule provided the temporalization of minjujuui in Korea with its peculiar intensity. This intensified the semantic competition over this term and its political appropriation. Therefore, the generalization process of democracy in Korea was accompanied by much more intense ideologicalization, politicization, and temporalization of democracy than in the West.