Carbon blacks (CBs) have been widely used as reinforcing materials in advanced rubber composites. The mechanical properties of CB-reinforced rubber composites are mostly controlled by the extent of interfacial adhesion between the CBs and the rubber. Surface treatments are generally performed on CBs to introduce chemical functional groups on its surface. In this study, we review the effects of various surface treatment methods for CBs. In addition, the preparation and properties of CB-reinforced rubber composites are discussed.

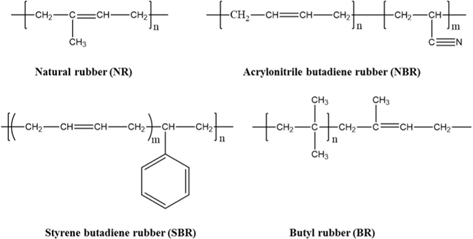

Rubber exhibits superior viscoelastic properties and improves the lifespan of products which continue to be transformed. At first, natural rubber (NR), which is composed of isoprene monomers, was obtained from nature. Later, as industries developed, synthetic rubbers were produced to supplement the production of NR. In particular, studies have been conducted on a new kind of rubber that is made of butadiene, namely, a copolymer of acrylonitrile butadiene rubber (NBR) and styrene butadiene rubber (SBR) as shown in Fig. 1 [1-6].

However, rubber lacks sufficient physical strength, which makes it unsuitable for various applications. For this reason, fillers, such as carbon materials and silica, are added to rubber to form rubber composites with improved mechanical behaviors [7-27].

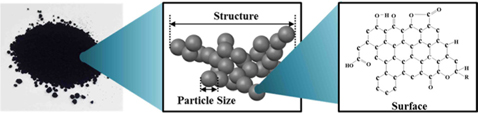

In recent years, carbon materials have been widely used as reinforcing agents in high-performance composite materials [28-35], adsorbents [36], electrochemistry [37], and energy storage materials [38]. Among various carbon materials used as reinforcing agents, carbon blacks (CBs) are the oldest carbon derivatives produced by the incomplete combustion of petroleum products, such as fluid catalytic cracking tar and coal tar. Moreover, the particle size, structure, and surface conditions of CBs (Fig. 2) make them popular reinforcing agents [19-21].

CBs contain more than 95% amorphous carbon, and their particle sizes vary from 5 to 500 nm. The physical properties of CBs vary with the production method and the raw materials used, which makes them suitable for applications in various fields. The mixing ratio of CBs in automobile tires is 50%, while that in other rubber products is approximately 30%. Relatively large amounts of reinforced CBs should be added to NR to attain acceptable mechanical properties. Cohesion occurs between CB particles due to chemical and physical bonds. The chemical composition of CB aggregates is 90%–99% carbon, 0.1%–1.0% hydrogen, 0.2%–2.0% oxygen, and a small amount of sulfur and ash. In addition, oxygen-containing functional groups, such as the carboxyl, hydroxyl, and quinine groups, exist on the surfaces of CBs. These are called surface functional groups. These surface functional groups increase the chemical and physical bonding between the CBs particles and the rubber matrix [39-43].

Therefore, the addition of CBs to rubber results in the formation of composites with improved mechanical properties, such as tensile strength, tearing strength, hardness, and abrasion resistance [4,22-25].

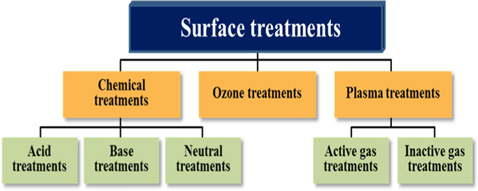

In addition, surface treatments of CBs render them suitable for practical applications in CB-reinforced rubber composites. The surface treatments mainly introduce chemical functional groups to the CBs surfaces. These functional groups increase the bonding between the CBs and rubber, which results in stronger interfacial adhesion compared to the case when untreated CBs are used. Various surface treatment methods may be applied to CBs, including chemical, plasma, ozone, electrochemical, and heat treatment [44-54].

In this paper, methods for the surface treatment of CBs and for the preparation of rubber/CB composites are reviewed in detail. A classification of surface treatment methods is shown in Fig. 3. In addition, the effects of various surface treatment methods on the mechanical properties of CB-reinforced rubber composites are discussed.

2. Methods and Effects of Surface Treatments on Carbon Blacks

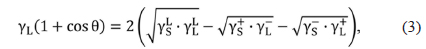

Surface free energy is commonly related to the mechanical properties of a material. Fowkes [55] proposed that the total surface free energy can be divided into two components:

where γL is the London dispersive component of surface free energy, and γSP is the specific (or polar) component of surface free energy.

The term γSP is further divided into two parameters using the geometric mean:

The surface free energies between the liquid and solid are calculated according to the following equation using van der Waals acid-base parameters:

where the subscripts S and L represent solid and liquid phases, respectively. Here, γL is the experimentally determined surface tension of the liquid,

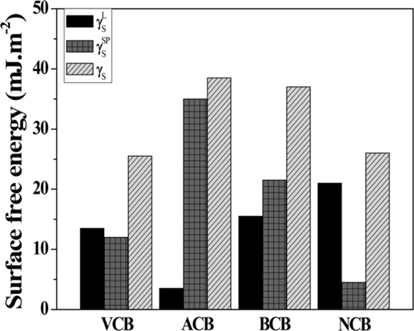

Virgin carbon blacks (VCBs) were produced at temperatures over 1400℃. Neutral-treated carbon blacks (NCBs), base-treated carbon blacks (BCBs), and acid-treated carbon blacks (ACBs) were prepared by treating VCB with C6H6, 0.1 N KOH, and 0.1 N H3PO4 for 24 h, respectively. Prior to each analysis, the CBs were washed several times with distilled water and dried in a vacuum oven at 90℃ [58-60].

Ketone (C=O) and hydroxyl (O-H) groups exist on the surface of VCB. According to some reports, an increased number of oxygen-containing groups, such as pyrone and chromene, and other stable basic surface functional groups has been observed in CBs produced at temperatures higher than 800℃. Thus, basic functional groups are already present on the surface of CBs produced at high temperature. For this reason, the intensity of the oxygen-containing groups rapidly increases through an acid-base interaction when CBs are treated with an acid. Meanwhile, the interaction between oxygen radicals and the surface of CBs generates oxides, and the intensity of the functional groups increases slightly when CBs are treated with a basic solution. When CBs are treated with a non-polar solution, a decrease in the intensity of the functional groups that exists on the surface of VCB is observed [61-63].

As observed from Fig. 4, for the case of ACBs, γSP of the polar component increases largely through the acid-base interaction between the surface of VCBs containing basic functional groups and the oxygen radicals from the solution. On the other hand, the BCBs show a large increase in γSP and γL of the non-polar component owing to the presence of stable basic functional groups. For NCBs, a decrease in the number of polar functional groups resulted in a decrease in the strength of the chemical bond between CBs or an increase in γL due to dispersion interactions resulting from the stabilization of the surface functional groups [55-57,59,60].

Ozone is composed of three oxygen atoms, and it resonates into four structures. Ozone, as a powerful oxidizing agent, is highly reactive with various organic and inorganic substances as well as with all metals except platinum and gold. Ozone is formed from OH radicals by various methods, such as silent electric discharge, electrolysis, the photochemical method, high frequency silent discharge, and irradiation. Among these, the silent electric discharge method is most widely used. In general, the CBs surface contains 3%–4% oxygen. However, ozone surface treatment of CBs breaks the unstable bonds present on the surface and produces highly reactive radicals and oxygen-containing functional groups. This causes a large increase in the number of oxygen-containing functional groups present on the CBs surface [64,65].

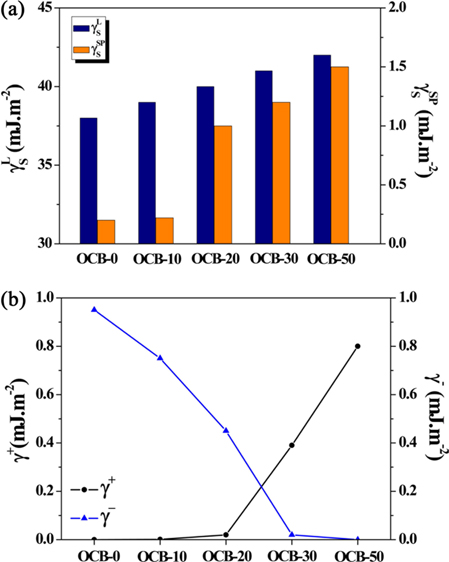

Ozone treatment of CBs was performed at various ozone concentrations: 0, 10, 20, 30, and 50 mg L−1 at room temperature. The as-prepared samples were labeled as OCB-0, OCB-10, OCB-20, OCB-30, and OCB-50 corresponding to the ozone concentrations of 0, 10, 20, 30, and 50 mg L−1, respectively [66].

The surface free energy of the CBs after ozone treatment is shown in Fig. 5. Fig 5a shows the polar and non-polar components of the surface free energy, and an increase in both components is observed. This can be explained as follows. Ozone with a strong oxidizing power attacked the unstable functional groups present on the CB surfaces resulting in the activation of a large number of stable functional groups, which in turn, led to an increase in the non-polar components of the surface free energy. In addition, Fig. 5b shows the γ+ (acid) and γ− (base) components of the surface free energy. After ozone treatment, γ+ increased greatly, while γ− decreased. This trend was observed because of the increase in the number of −OH and −COOH groups on the CB surfaces caused by ozone treatment. As a result, the polar component of the surface free energy also increased with an increase in γ+. In addition, the polar functional groups present on the CB surfaces react and form a chemical bond with the −CN group of NBR. Therefore, the interactions of interface between NBR and the CBs were activated by an increase in the number of the oxygen-containing polar functional groups present on the CB surfaces after ozone treatment. Finally, the cross-linking density increased due to the network structure [65].

Plasma is a gas in which negatively charged electrons are separated from the positively charged protons at high temperature. In plasma, interactions between particles produce light, and the active movement of the particles causes a high reactivity. Plasma gases used for the surface treatment of polymers can be classified into inactive gases, such as argon, helium, and nitrogen, and active gases, such as ammonia and carbon tetrafluoride. For each type of gas, the surface is modified by the introduction of specific functional groups on the surface [67-69].

Plasma surface treatment is a dry process that produces less pollution and does not cause changes in the mechanical properties of composites, such as strength and modulus of elasticity. In contrast to other treatments, this process changes the surface characteristics [70].

2.4.1. O2 plasma treatments

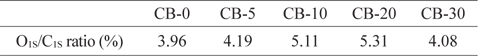

The plasma power used for oxygen plasma treatment was 20 W at a frequency of 13.56 MHz under a pressure of about 0.1 kPa. The treatment was carried out for various durations of 0, 5, 10, 20, and 30 minutes for which the as-prepared samples were named CB-5, CB-10, CB-20, and CB-30, respectively [67].

O2 plasma surface treatment oxidizes the surface of polymers and introduces oxygen-containing polar functional groups, such as hydroxyl, carboxyl, quinine, and lactone. These polar functional groups increase the hydrophilicity of the surface of hydrophobic polymers and improve their wettability and adhesion. It is generally known that the introduction of oxygen-containing polar functional groups on the CB surface by oxygen plasma treatment increases the interfacial adhesion between CBs and organic elastomers, such as butyl rubber (BR), NR, and NBR, which is polar rubber [67-69].

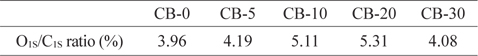

Table 1 shows the oxygen content of the CB surface in terms of O1S/C1S ratio after plasma surface treatment. As seen in Table 1, as the plasma processing time was increased, increases in the O1S/C1S ratio were observed. The most significant increase of 5.31% was observed with the processing time of 20 min. The ratio decreased to 4.08% when the processing time was 30 min [67].

[Table 1.] Results of the O1S/C1S ratio of the carbon black treated by oxygen plasma studied

Results of the O1S/C1S ratio of the carbon black treated by oxygen plasma studied

2.4.2. Plasma treatments in N2 condition

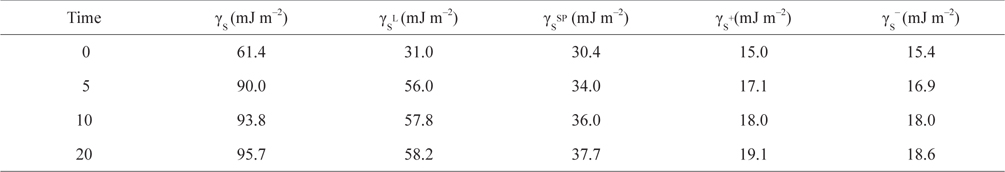

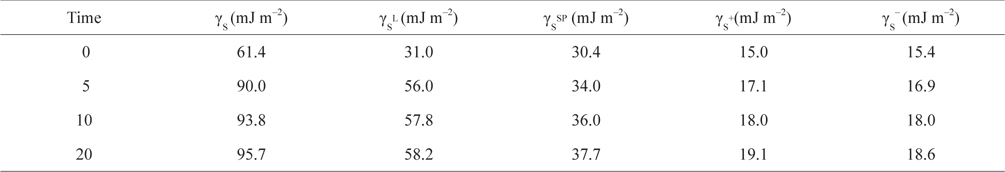

Plasma treatment of CB samples was carried out using a radio frequency for N2 gas. The radio frequency (13.56 MHz) generated by N2-plasma was operated at 30 W. The input treatment time for the N2-plasma treatment was varied to 0, 5, 10, and 20 min under a pressure of 0.1 kPa [71].

As seen in Table 2, an increase in the duration of the plasma treatment of the CB samples resulted in an increase in the γs+ and γs− of the CBs along with an increase in the non-polar components. The oxygen or hydrogen released from the surface of the CBs by the plasma surface treatment was plasmanized, which activated the polar functional groups present on the surface. In addition, the non-polar components increased greatly. In the case of plasma surface treatment using inactive gas N2, the parts of the CB surfaces having the most unstable chemical bonds were attacked and either hydrogen or oxygen was released. The stable functional groups that remained on the CB surface or the surface itself were stabilized. As a result, the non-polar components also increased significantly [70].

[Table 2.] Surface tension components and parameters of the carbon blacks studied, measured at 20℃

Surface tension components and parameters of the carbon blacks studied, measured at 20℃

2.5. Treatment of other carbon materials

2.5.1. Graphene

Three grams of graphene was dispersed in 300 mL of a concentrated H2SO4:HNO3 solution at 35℃. The mixture was stirred for 12 h followed by sonication for 1 h. The reaction mixture was then filtered and washed with double-distilled water and acetone until the pH reached 6-7. The resulting oxidized graphene was then dried under vacuum at 80℃ for 12 h [72].

2.5.2. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes

Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) were produced by chemical vapor deposition and had a diameter of 10–30 nm and a length of 20–50 μm. The MWCNTs were chemically purified in 5 M nitric acid for 2 h at room temperature. They were filtered and thoroughly washed with distilled water several times and then dried in a vacuum oven for 24 h at 60℃. The purified MWCNTs were immersed in 2 M phosphoric acid and were treated for 2, 5, and 10 h [73,74].

2.5.3. Activated carbons

2.5.3.1. Preparation method I

The nature of activated carbons (ACs) depends on their ash content because liquid-phase modification can cause the removal of some inorganic species followed by structural changes. The ACs were obtained by chemical surface treatment in an aqueous solution consisting of 35 wt% HCl and 35 wt% NaOH for 24 h, which thus modified the AC surfaces. Prior to use, the residue of chemical solutions in the modified ACs was removed by Soxhlet extraction by boiling with acetone at 80℃ for 2 h. The treated ACs were washed several times with distilled water and then dried in a vacuum oven at 85℃ for 24 h [75,76].

2.5.3.2. Preparation method II

ACs were treated by ozone produced from pure oxygen at the rate 6 g O3/h. The reaction time was varied from 1–4 h and the corresponding samples obtained after treatment were denoted as 1, 2, and 4 h, respectively. The surfaces of the samples were analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectrometry [52].

2.5.4. Carbon fiber

2.5.4.1. Preparation method I

This method was used for the oxidation of carbon fiber (CF) s. A 3:1 mixture of concentrated H2SO4/HNO3 was sonicated at 60℃. In a typical reaction, several small pieces of CF paper were added to 60 mL of the above mentioned mixture in a reaction flask. The flask was placed in an ultrasonic water bath operating at 152 W and 47 kHz and maintained at 60℃. The treatment duration was varied from 10 s to 240 min. The treated substrate was then washed twice with de-ionized water [77].

2.5.4.2. Preparation method II

CFs were used in various plasma treatments. Prior to the plasma treatments, CFs were washed with trichloroethylene and were then heated at 120℃ in a vacuum oven overnight. All the treated CFs were stored

3.1. Natural rubber/carbon blacks composites

NR was added to the mixing chamber having a rotor speed of 70 rpm. The CBs were then added and the contents were mixed for 2 min. The rotors were stopped and the filler caught in the chute was then swept down into the chamber and mixed for 5 min before dumping. Dump temperatures were around 150 ℃. The density values determined by pycnometer were used to maintain a volume fraction of 0.20 for each grade of filler. This is equivalent to 50 phr mass loading of the unmodified CBs. A second mixing step was performed in a laboratory two-roll mill [79].

3.2. Butyl rubber/carbon blacks composites

The 10–100 phr samples of BR were prepared using a high-abrasion furnace, a fast-extruding furnace, and a semi-reinforcing furnace. The preparation techniques have been described elsewhere. The composites were vulcanized at 150℃±2℃ under a pressure of 40 kg cm−2. The duration of vulcanization was 30 min. The samples were thermally aged at 90℃ for 35 days to attain reasonable stability and reproducibility. Disc-like samples with a thickness of 3 mm and a diameter of 10 mm were obtained [80-82].

3.3. Acrylonitrile butadiene rubber/carbon blacks composites

3.3.1. Preparation method I

The NBR/CBs composites were prepared by mixing bio-based engineering polyester elastomer with 40 phr of carbon blacks and 2 phr of dicumyl peroxide at 50℃ and a speed of 40 rpm. All the composites were finally vulcanized under 15 MPa at 160℃ for 20 min to produce 2 mm thick sheets [83].

3.3.2. Preparation method II

The NBR/CBs composites were produced in a laboratory two-roll mill. The mixing ratio of CBs was fixed in the range 0–30 phr. The rubber composites were prepared by vulcanization of the rubber compound during compression molding in a hydraulic press. This was done under a pressure of 1500 psi and at temperature of 150℃ using a 1 mm thick mold [84].

3.4. Styrene butadiene rubber/carbon blacks composites

3.4.1 Preparation method I

We used SBR as an elastomer for preparing SBR/CBs composites. SBR is composed of 24.1% styrene and 75.9% butadiene. The CB-filled rubber composites were prepared using a mixer at a speed of 70 rpm at 110℃–150℃ for 4 min. The weight ratio of SBR:CBs was fixed as 2:1 [85,86].

3.4.2 Preparation method II

SBR/CBs compounds with varying filler concentrations were prepared as follows. Approximately 5 g of SBR cut into small pieces was placed in a Petri dish and dissolved in 200 mL of benzene. CBs were added to the rubber solution, and the solvent was evaporated. The film composed of rubber and CBs obtained after the evaporation of benzene was processed on a cold two-roll mill. Care was taken to ensure thorough dispersion of the filler into the rubber. After mixing, the compounds were compression molded for 1 h at 145℃ to prepare about 1 mm-thick film samples [87].

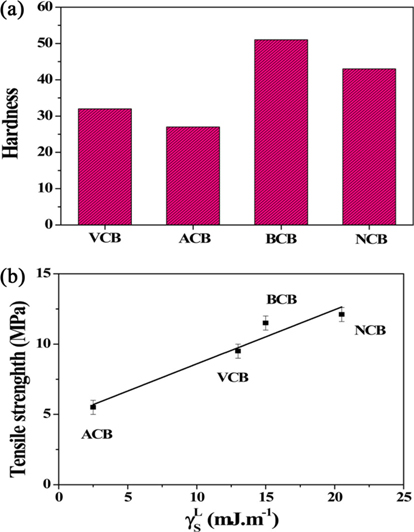

4.1. Rubber/chemical-treated carbon blacks

Park et al. [56,57] performed chemical surface treatments of CBs and investigated changes in the hardness of rubber reinforced with surface-treated CBs. Fig. 6a shows the changes in the hardness of CB-reinforced rubber after chemical surface treatments. Also, Fig. 6b shows the dependence of tensile strength on the London dispersive component of the surface free energy of the resulting composites, and a model of these properties is shown in Fig. 7. The hardness or elastic modulus of rubber depends heavily on filler properties, such as particle type and size; surface properties; and the cross-linking density of the polymer. The basic functional groups present on the surface of VCB and the active acid-base interactions lead to an increase in aggregation and a decrease in the cross-linking density of the polymer, which in turn, leads to a decrease in the hardness of rubber. In the case of BCB or NCB, the hardness increases, and the increased dispersion force of the CBs strengthens the filler and improves the cross-linking density of the polymer. NCB has a greater London (non-polar) component than BCB. However, a decrease in the number of surface functional groups weakens the physical bonding between the polymer and filler. Hence, NCB shows a lower hardness value [88]. Dai et al. [89] performed surface treatments on CBs using an acid and a base and measured the tensile strength and elongation of CB-reinforced rubber. The mechanical properties of BCB were improved according to the mechanism described above. In addition, the difference between the acid and base surface treatments was larger in terms of tensile strength than elongation [90].

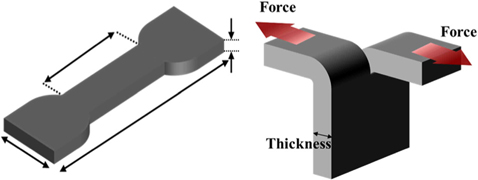

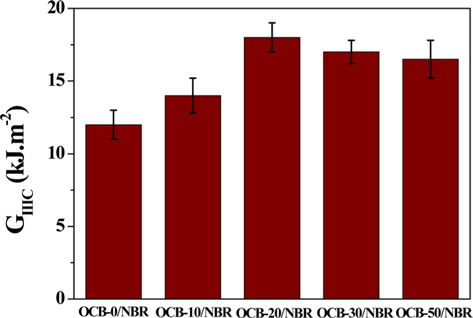

4.2. Rubber/carbon blacks treated with ozone

Park et al. [65] treated the surface of CBs with ozone and investigated changes in the hardness of CBs. The tearing energy (GIIIC) measurement results of CBs/NBR composites are shown in Fig. 8. The GIIIC was characterized by a trouser beam test for analyzing the mechanical behavior of the composites, as shown schematically in Fig. 7. As shown in Fig. 8, the GIIIC of the ozone-treated composites significantly increased compared to OCB-0/NBR. This result shows a tendency similar to those of the cross-linking density. The polar functional groups present on the surface of CBs improved the interfacial bonding with NBR, and the mechanical properties of the interface increased according to the mechanism described above [91]. According to the experiment performed by Léopoldès et al. [92], the elastic modulus of CBs increases after oxidative gas-treatments [50].

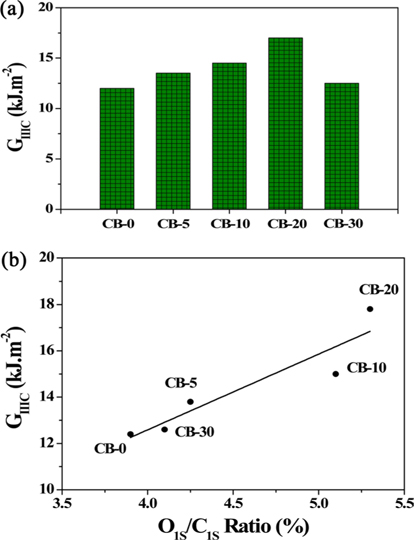

4.3. Rubber/carbon blacks after plasma treatments

Park et al. [67] performed O2 plasma surface treatments on CBs and investigated the corresponding changes in the GⅢC of rubber filled with O2 plasma-treated CBs. Fig. 9 shows variations in the mechanical properties of the interface with GⅢC. The increase in GⅢC for the rubber composites filled with O2 plasma-treated CBs was greater than that for the rubber composites filled with VCB. The GⅢC of CBs/rubber composites increased generally with the duration of the surface treatments. In general, polar functional groups present on the surface of CBs react and form chemical bonds with the CN group of NBR when NBR is filled with CBs. Therefore, carboxyl, hydroxyl, lactone, and carbonyl groups formed on the surface of CBs by O2 plasma treatments increase the interactions between NBR and the interface, and as a result, these composites lead to substantial improvement in the mechanical properties of the interface as compared to that shown by of the rubber composites filled with VCB [93-95]. Akovali et al. [96] introduced additives after surface treatment of CBs using plasma and examined the change in the hardness of CB-reinforced rubber. As a result, the cohesion between other additives and rubber was strengthened after the plasma surface treatment of CBs. This was determined by tensile strength measurements [97,98]. Mathew et al. [99] found that there was less interaction between plasma-treated CBs and other fillers in rubber compounds from Payne effect data. This increases the affinity of CBs for rubber; thus, the mechanical properties of rubber composites are improved [100,101].

In this paper, we have reviewed various surface treatment methods for CBs and the procedures used to introduce functional groups onto CB surfaces. Good interfacial adhesion between CBs and rubber has been observed after the treatment of CBs due to changes in the surface free energy. We have reviewed the preparation methods in detail and have also discussed the mechanical interfacial properties of CB-reinforced rubber composites, such as hardness, tensile energy, and tearing energy in this system.