It is Malaysia’s worst water crisis ever, surpassing the 1998 water shortage when Klang Valley folk had to suffer six months of rationing. There are only 80 days to the critical stage, and there can only be a reprieve if the state’s two major dams get as much rainfall this month as they usually do in November, one of the wettest months of the year’ -

Throughout 2013, Kuala Lumpur and surrounding areas suffered consecutive ‘spates of critical water cuts and shortages’ (Mak, 2014). On 21st February 2014 the Malaysian government recognized that this had become a major crisis requiring ‘severe rationing’ as well as consideration of further policy remedies. Following this, recommendations were made to the public to stop wasting water (with no great effect) and an initiative approved to try ‘cloud-seeding’ to break the drought (Ruslan, 2014). Yet, weeks later on March 7th, the government also announced plans to degazette ‘important forest reserves in the surrounds of Kuala Lumpur’ which served as a ‘vital water catchment’ area for the city (Chi, 2014). Indeed much media commentary and social media discussion about the emerging crisis has focused on the wider and long-term challenges of ensuring the future sustainability of local and national water resources. A

In this way and as discussed below, Malaysia’s on-going water crisis continues to exemplify Huitema and Meijerink’s (2009, p.3) point that water policy issues tend to represent examples of ‘wicked problems’ - that is, complex problems also typically involving a human or social dimension which resist simple one-shot policy or technical solutions (e.g. Conklin, 2005). This paper will discuss how the Malaysian water crisis also represents an exemplary instance of the opportunity as well as challenge of university-industry partnerships for problem-solving based on interdisciplinary foundations.

On this basis it will also explore a framework for more effective and integrated policy solutions that also includes more specialized domains of scientific and technological knowledge as well as integrating principles of stakeholder convergence and knowledge management. As a case study exploration of the larger challenge of sustainable policy development, the paper will focus on exploring the key elements and general approach likely needed to ensure Malaysia or any other country has a robust, integrated, and sustainable water policy framework for the future.

Despite the relative abundance of rainfall and plentiful surface water resources in Malaysia, recent reports suggest that the country is faced with the prospect of long-term water scarcity (AWER, 2011; Teng, 2011). Water governance in Malaysia is complex, multi-layered and embedded within various local and national political agendas (Tan, 2012). The root of much of the complexity lies in the ownership and responsibility for water. Malaysia’s State authorities have control of water resources (rivers, streams, reservoirs, etc.) whilst the Federal Government oversees water supply and wastewater service provision (Chin, 2008). Subsequently, there have been on-going disagreements between State and Federal levels of government. Furthermore, responsibility of water cuts across as many as eight different government departments and agencies adding to the multi-tiered governance of the industry (Tan, 2012). Currently, there are twenty-four water service providers in Malaysia consisting of a mix of privately owned, state owned and some joint private-state owned ventures. Whilst there is an overseeing commission for national water policy, the National Water Resources Council (NWRC), there is not one definitive water policy or overarching strategic direction for the management of the water industry (Abidin, 2004).

The predicted scarcity is thus less related to changes in rainfall patterns than to the diminishing availability of water resources, insufficient treatment capacity for urban populations, and the inadequacy of the current water policy and management regime. Related to this are growing concerns over dilapidated infrastructure (i.e. non-revenue water as high as 40 percent in some cities), urban water pollution concerns, institutional challenges and a complex diversity of related factors including on-going excessive wastage (Elfithri, 2011) which continue to beset Malaysia’s water industry. However, the emerging crisis goes a long way back. The Malaysian Water Partnership (2001) outlined at the turn of the century the following warning made in response to the findings of an international project undertaken to develop ‘national water visions’ in the Asia-Pacific region: ‘lately the water supply situation for the country has changed from one of relative abundance to one of scarcity.’ As initial signs of future issues emerged in the 1980s there were piecemeal efforts to privatise the sector across different states and territories (e.g. Santiago, 2005). This strategy was eventually replaced by a new series of policy changes over the last decade generally aimed at restructuring the Malaysian water sector in terms of ‘centralising and liberalizing its heavily indebted water sector to improve services’ (Borschardt, 2009).

More recently policy efforts to address Malaysian water dilemmas have tended to refer to the standard notion of a ‘better water future’ outlined in Malaysia’s 2020 Vision to strive for developed nation status. In terms of key related objectives (water for the people, food, rural development, economic development and the environment) the standard vision is to ‘ensure adequate and safe water for all (including the environment)’. The challenge of this process is epitomized by the title of a recent report ‘Malaysia continues the thorny process of water sector restructuring’ (Majudi, 2011). This article focused on how a series of water policy changes since the landmark ‘Water Services Industry’ and ‘National Water Services Commission’ Acts of 2006 and 2008, respectively, have reflected conflicting tensions between local and central planning as well as public and private sector involvement in the overall Malaysian water sector or industry.

The current ‘reform impasse’ discussed by Majudi and others is deeply entrenched in the country’s most populous state, Selangor, where State and Federal governments, respectively, have been unable to agree on water asset value and ownership (Weber, Memon and Painter, 2011; Khailid, Rahman, Mangsor et al, 2012). Despite significant debt liabilities held by the State government and private water companies, the prospect of potential tariff hikes and reduced control of water has led to considerable State and public opposition. Furthermore, the disagreement has stalled the completion of an inter-state water transfer project that could seriously compromise Selangor’s future water security (Lingan and Arbee, 2012; Bernama, 2012). The level of disagreement and disharmony amongst macro-level stakeholders has reached new heights of potential crisis since resolution may only be found through expensive litigation in a court of international arbitration (Lim, 2012). Whilst the major crisis of 2014 has emboldened the government to try and resolve these conflicts once and for all, it remains to be seen how successful these efforts will be.

The challenge then is to achieve sustainability in practice and not just in the rhetoric of policy. In other words, a framework seems to be needed to sufficiently and effectively provide strategic guidance on the long-term sustainability of Malaysian water industry. For the purposes of this paper we take the lead of the 1991 UK ‘Water Industry Act’ and use the term ‘water industry’ in the wider sense - that is, not just synonymous with an economic or market

The link between a case study focus on the Malaysian water industry and the challenges of sustainable policy building will be developed in relation to the need for a more integrated or systemic approach to policy design and development as a mode of complex problem-solving. Such an integrated approach will be conceived and applied in relation to four interdependent aspects: science and technology innovations, environmental (vs. economic) sustainability challenges, human resource performance and coordination, and key stakeholder perspectives. The challenge of achieving a sustainable policy focus for the Malaysian water industry thus provides a particularly interesting and useful example of the ever increasing global need for an integrated, emergent and optimal approach to achieving sustainable policy solutions for complex problems.

1. Applying an Interdisciplinary Research Framework to Complex Problems of Industry

This paper also represents the application of an interdisciplinary research framework to enhance as well as support university-industry collaborative research. In particular, collaborations that can address complex and policy-related challenges or problems faced by various industry hubs of human work, activity, and common resources in a changing world and emerging knowledge economy and society. As Rycroft and Kash (2004) anticipated, the growing ‘complexity challenge of [sustainable] organizational plans, corporate strategies or national policies’ indicate how policy research provides a natural focus for both ‘internal’ multi-disciplinary collaboration within universities and also ‘external’ opportunities for university-industry collaboration. In this way, interdisciplinary policy research can integrate and harness a wider range of applied research expertise towards the kinds of authentic solutions and outcomes to various challenges increasingly needed by business, government and society. Trewhella (2009) has pointed out how interdisciplinary research is the crucial basis for the most effective ‘high performance teams… [to be able to] create knowledge that drives innovation’. As the Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy (COSEPUP) (2004: 26) has influentially defined the concept of an important new emerging paradigm of research:

Interdisciplinary research (IDR) is a mode of research by teams or individuals that integrates information, data, techniques, tools, perspectives, concepts, and/or theories from two or more disciplines or bodies of specialized knowledge to advance fundamental understanding or to solve problems whose solutions are beyond the scope of a single discipline or field of research practice.

The emerging field of interdisciplinary research has a particular connection to the central idea of ‘wicked problem-solving’ (e.g. Kolko, 2012). This is that governments, corporations and societies are increasingly dealing with complex challenges and issues that resist simple solutions, but requite collaborative across areas of knowledge as well as the public-private divide (Klein, 2004; Repko, 2008). The convergent idea of interdisciplinary approaches to complex or wicked problem-solving is also informed by a range of models - such as complexity, fractal and chaos models of science - which in various ways support a convergent ‘self-organising systems’ view of the relation between nature and human activity in changing, complex environments (Forrester, 1991; Berkes, Colding and Folke, 2003). As Klein (2004) put it, ‘in recent decades the ideas of interdisciplinarity and complexity have become increasingly intertwined… the implications [of this link] span the nature of knowledge, the structure of the university, the character of problem-solving, [and] the dialogue between science and humanities’. This new emerging version of systems theory cuts across the traditional separation between the natural and social sciences on one hand, and on the other mechanical versus digital technologies. In our related version of this in terms of various knowledge and organizational structures of human activity, authentic self-organising systemic resilience in the face of changing or complex environments is inevitably a function of deep rather than surface level accountability or integrity and also feedback processes (Richards, 2013).

In terms of applied methods of inquiry, data collection, analysis and applied problem-solving, there are a range of related theories and concepts, but also specific research methodologies which are either directly supportive of or indirectly useful to an interdisciplinary inquiry or even experimental, approach to authentic complex problems or policy challenges (e.g. Schon and Rein, 1994). This includes such related models as design experiments, grounded theory development, participatory action research, knowledge management, and ‘mixed-mode’ methodologies of research evaluation. As the COSEPUP principle outlines, the interdisciplinary research framework represents a convergent methodology open to include and reconcile a range of different methods. Trewhella (2009) points out how the key to such a framework in practice is to be able to go ‘beyond simple collaboration and teaming to integrate data, methodologies, perspectives, and concepts from multiple disciplines in order to… assemble and create a common language and framework for discovery and innovation.’

In other words, interdisciplinary research has particular application to alternately but also convergently achieve a

2. Integrated Industry-Based Problem-Solving for Sustainable Policy Development

The challenges of the Malaysian water sector thus exemplify how a systems approach to complex problems might be most usefully understood and applied also as

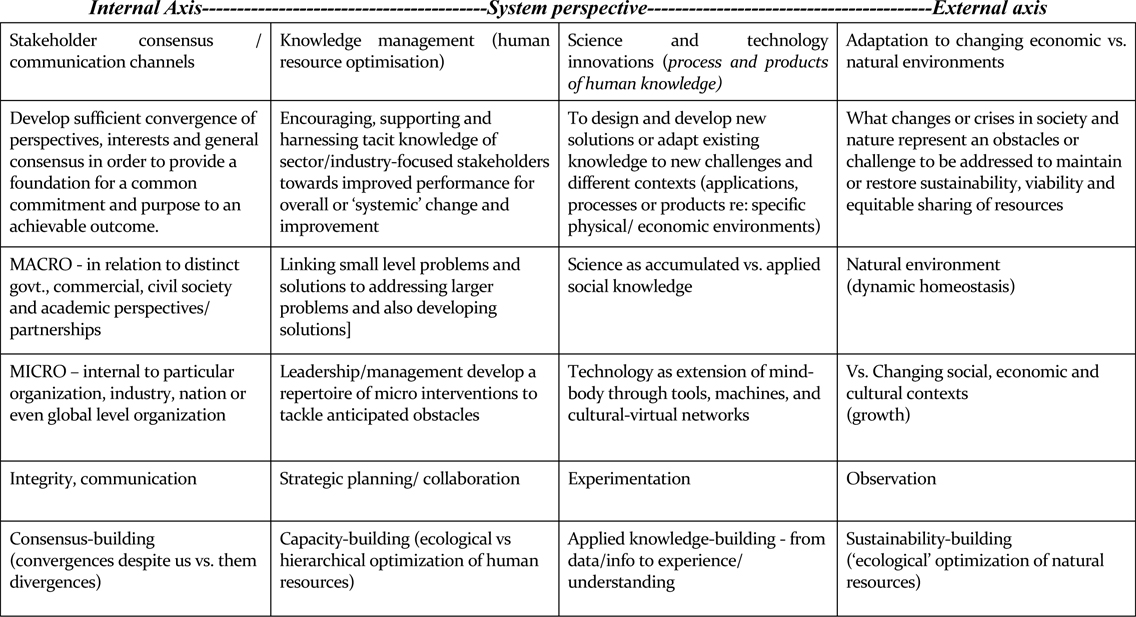

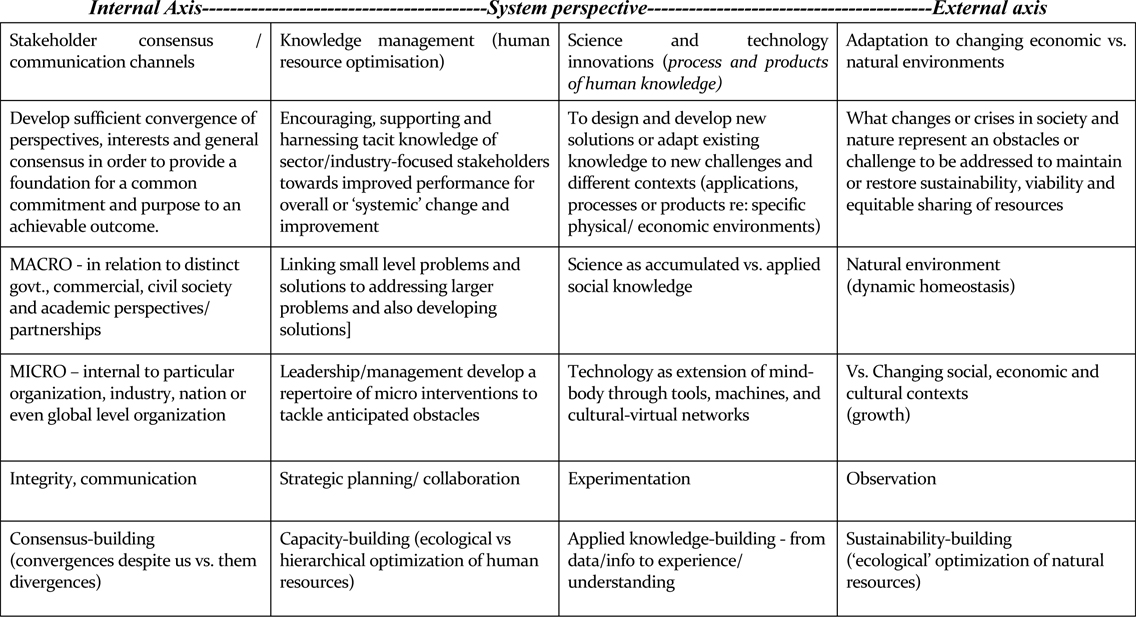

Complex problem-solving and related policy solutions might be the most effective approach in terms of four basic stages (Richards, 2013): first, identify a central problem in the most strategically relevant and useful terms; second, break this down into the key related problems and critical factors; third, not only seek manageable solutions or remedies for these related problems or issues, but do so in terms of their specific interdependent relation and local as well as possible global context; and fourth, develop an overall solution, remedy and/or planning strategy around four generic or ‘macro’ interdependent aspects: a) science and technology innovations, b) environmental sustainability challenges, c) human resource performance and coordination, and d) stakeholder perspectives. These aspects provide the focus for outcomes-based problem-solving geared towards the ‘optimisation’ of natural and human resources, a ‘green’ approach to new science and technology solutions, and the process of achieving a foundation to sustainable change also through consensus-building and focusing on common purposes. As also depicted in Table 1, a sustainable policy framework therefore also involves four distinct aspects and requirements or elements of integrated problem-solving and policy-building reflecting corresponding modes of knowledge:

Four critical elements of integrated industry-based problem-solving for sustainable policy development

3. Applying an Interdisciplinary Framework to the Diverse Challenges of the Malaysian Water Industry

The integrated and cross-disciplinary problem-solving framework outlined above has many useful applications. But above all else it provides a basis for seeking to engage stakeholders in constructive, collaborative, and problem-solving research which will harness the tacit, local and social knowledge of all those within different levels of industry organization. As an exemplary industry case study in a project focused on sustainable policy development linking government, business and community macro-stakeholders, we collaborated with the Malaysian Water Association in organizing a seminar involving a diverse group of informed industry stakeholders from government agencies, the private sector, and the wider society (Padfield et al, 2014). The stated purpose of the seminar was to discuss present and future Malaysian water industry challenges with a view to better recognise and appreciate the possible elements of a sustainable, robust and integrated water policy framework for the Malaysian context. It was framed as a proposed collaborative macro-stakeholder effort to develop the outlines and relevant aspects of an integrated industry problem-solving framework that might also provide the foundation for future efforts to develop a sustainable Malaysian water policy option or model.

A common view of a central problem gradually emerged from the various discussion of a series of related points or ideas. It was clear that many felt that Malaysian society in general no longer valued ‘water’ sufficiently to stop wasting, polluting and unequally sharing a common resource. Conflicting values within and across government, business and community sectors were seen as the cause as well as symptoms of the general problem that what should be still an abundant resource had become a focus of disagreement struggling to deal with a growing current scarcity of clean quality water to meet the future needs of all. Although the central problem was conceived in various related ways perhaps one of the most useful ways that this was expressed as follows:

In light of a changing climate and the increased needs and demands of a growing population and economy, what policy framework could best promote the required optimization of organizational, social and ‘industry/sector’ responses to achieve a physical and also technical optimization of Malaysian water resources?

What also emerged as the discussion proceeded from initial small groups to a general forum discussion based on group reports was the sense that the central problem was informed by two key related negative cycles or self-fulfilling prophecies. The first was linked to the perceived need for a general mind-set change and public awareness program in Malaysian society at large to get people to recognize that even in Malaysia clean water is becoming increasingly scarce and that the ‘true cost’ of a reliable quality water supply needs to be better appreciated. The second negative cycle was framed in terms of the perception that because governments often seemed disinclined to bring in unpopular reform along ‘user-pays’ lines directed at the utility-user-cum-consumer that this was would make it more difficult in the future to change. However, this was before the current Malaysian water crisis - which is putting enormous pressure on government as a key stakeholder in the industry to act more decisively and constructively.

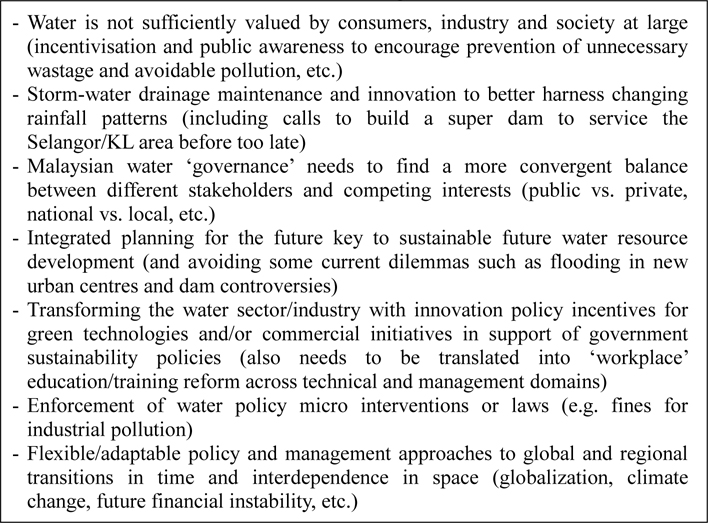

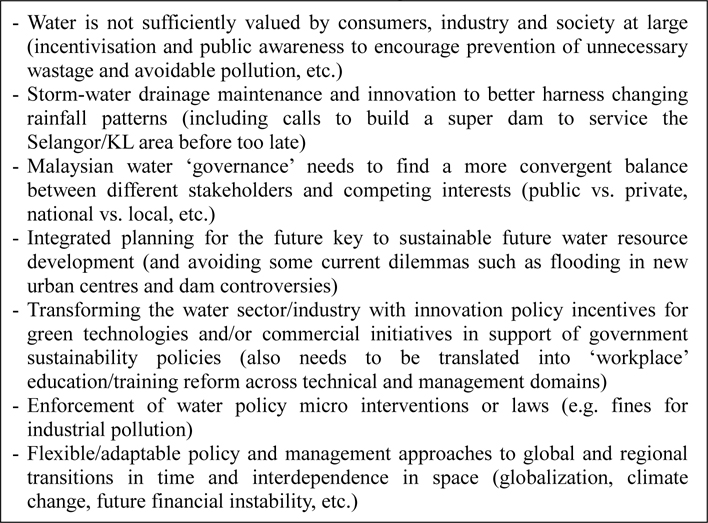

Table 2 summarises the key contributing factors initially identified by stakeholders in the seminar. Whilst the key contributing problems of a central problem focus may be prioritized in terms of a range of internal and external factors or issues, from a systemic point of view each of these represents an important interdependent aspect and part of the main problem identified. In this way the seminar group discussions encouraged an integrated perspective towards also prioritising, balancing and engaging simultaneously the ‘parts’ of the general challenge. Just as the Malaysian Water industry also represents a network of diverse interests, stakeholders and perspectives across a range of divides (public vs. private, management vs. technical, macro vs. micro, global/regional/national vs. local, etc.), so too an interdependent and convergent set of solutions will be needed.

[Table 2] Outline of key contributing issues/ critical factors

Outline of key contributing issues/ critical factors

This may be further understood in terms of how a policy as distinct from management perspective for better engaging future needs, requirements and vision is generally framed by the central macro-stakeholder dynamic. In other words, governmental or public responsibilities for sustaining (and also ‘maintaining’) society and nature need to balance with private sector or market forces of growth, profit and progress as the basis for needed ‘research and development’ innovations and investment in the future. Across local, state, national and regional as well ultimately global contexts it remains the responsibility of government agencies to defend the sustainable future interests of both the wider community and also the natural environment from merely short-term commercial and profit-driven development agendas of the market place - in this case to optimize the harnessing and use of water resources. Feedback was provided that whilst earlier efforts to privatize the industry had proved a failure the central planning tendencies of recent Malaysian government policy initiatives to restructure the water industry- had not resolved this basic dilemma. In other words, an either/or approach was seen to reinforce rather than resolve a range of related problems to do with the wastage, pollution of existing water resources, and related failures to maintain and upgrade existing storm-water drainage on one hand, and on the other, to apply integrated water management plans to new urban development (e.g. Tan, 2012). There was a general consensus that policy-makers had so far shied away from some of the critical decisions needed for greater sustainability (i.e. were not prepared to risk ‘short-term unpopularity’) because of a possibly mistaken assumption that the ‘rakyat’ (or people) would not generally accept the need for change. Most seminar participants enthusiastically and unanimously endorsed the need for greater convergence across a range of distinct knowledge and stakeholder domains.

Towards the end of the seminar participants were surveyed about what they considered to be the most pressing research themes that should be prioritised. A list of fifteen identified themes was subsequently reassessed, regrouped and prioritized into six major themes used to focus on the emerging water crisis:

4. Applying an Integrated Framework of Industry Problem-Solving

The various groups of the seminar discussed above generally found the

As some seminar groups explored further, a particularly useful subsequent stage of policy-building is to build into the problem-solving process the anticipation of possible future obstacles and issues. For instance, current decision-making and planning within the Malaysian water industry will need to include both the external factor of climate change and the internal factor of possible future urbanization needs and tendencies. This integrated framework encourages a more interdependent and integrated anticipation of future policy design, development and implementation challenges. Likewise, the interplay of macro level outcomes and objectives and micro level details is more effectively applied to inform processes of decision-making and planning when considered within these distinct domains as well as overall.

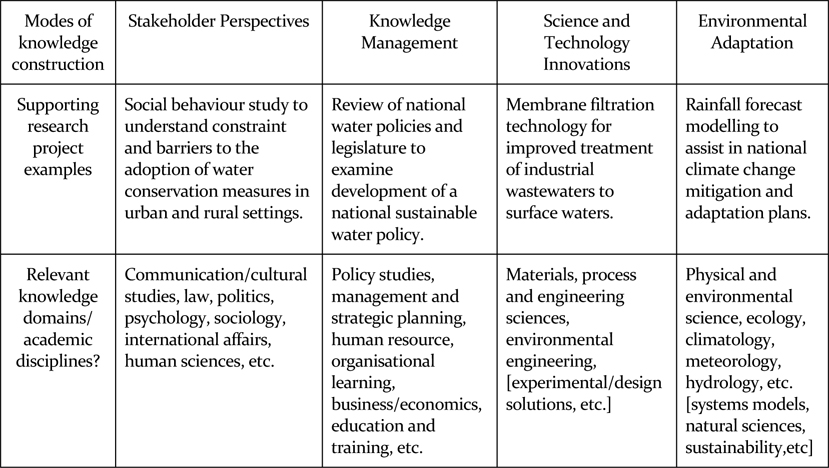

As Table 3 shows, such an integrated approach should also be approached within as well as across the distinct knowledge domains outlined. Just as managers and policy-makers within public or private sector organizations need to better appreciate their role in supporting and harnessing the benefits of ‘science, technology and innovation’, so too scientists and technicians within the water industry in Malaysia and elsewhere can and should use an integrated context to prioritize future priorities of maintenance as well as research and development. On one hand there was much discussion about the need to move from top-down leadership within organizations to a better supporting, harnessing and engaging with the tacit knowledge of all human resource groups. This reflects a related need of leadership to engage with what Frisch (2012) calls a ‘portfolio of teams’ within a particular organization or within the industry as a whole. On the other hand, there was a good deal of discussion about what might or should be future science and technology ‘research and development’ priorities to support the industry. Reflecting the need to adapt global to local contexts, one participant provided an eloquent case about how wastewater treatments methods in Malaysia needed to be either better adapted or improvised in relation to the local context (e.g. Ugang and Henze, 2004). Using the example of how high levels of ammonia (as well as other toxic chemicals) in many local water systems were linked to related problems of drainage leakage (and the selection of suitable piping), he effectively argued that further priorities about drainage or decisions about particular water treatments were more likely to be effective and sustainable if current water testing regimes were improved.

Applying an integrated framework of industry problem-solving to a checklist of related aspects

As set out in the introduction, the development of more relevant research collaborative initiatives between industry stakeholders and academia may be critical to achieve more integrated, optimal and sustainable policy directions in the future Malaysian water industry. Such a change might be needed to more effectively address a range of related issues and challenges ranging from the smaller, more localised issues to the more complex problems that converge to inform the Malaysian water crisis. Therefore the formulation of an organised plan for industry-related research and development is an important issue. The framework outlined above has set out a logical and organised method of identifying research needs and concerns relevant to specific stakeholder groups and knowledge modes which address the wider needs of the industry. There is still the additional problem of how to bring parties and funding agents together to merge research priorities and generate more productive industry-university collaboration. Moreover, the following section explores the question of prioritizing related research priorities as a basis for seeking appropriate and effective funding as well as other support.

In Malaysia, water research tends to be the domain of a government supported institution, the National Hydraulic Research Institute (NARHIM), and a handful of research focused universities. NAHRIM conducts basic and applied research on water such as water resources, river, coastal, geohydrology and water quality (NAHRIM, 2012). Universities undertaking water research include Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Universiti Malaya (UM) and Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM). These universities have international track records in water research with particular expertise in water and wastewater treatment technologies (Chelliapan, Wilby and Sallis, 2006; Ujang and Hense, 2006) and applied hydrological research (Yusop et al, 2006; Shamsudin et al., 2014). Thus a related characteristic of the Malaysian water research landscape is how there is keen university competition for government research funding grants. However this does not necessarily lead to a harnessing of expertise, skills and knowledge for the benefit of the water industry. A more effective model might encourage more interdisciplinary academic collaboration within but also across different universities.

To date in Malaysia there is still no overarching national research strategy or institute coordinating current research activities in the industry or across the universities and research bodies. Research tends to takes place in the areas that different researchers and funding agencies think are in most need. Two government ministries, the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Science and Technology, largely allocate funds for research projects undertaken by NAHRIM and aforementioned universities. The result of such a reliance on governmental funds appears to be a greater emphasis on hard science and engineering focused (i.e. specialized and isolated) research than a more comprehensive portfolio of projects addressing the wider needs of industry. Two related points indicate this. First, governmental funding bodies have a track record of funding a smaller number of research projects at high cost (rather than many projects at lower cost) with accompanying higher end technology and cutting-edge science. A case in point is the water desalination plant project in Sarawak. Second, in the past interdisciplinary research applications involving a ‘social science’ focus also on issues of governance, policy and any possible conflict of stakeholders have often been perceived as irrelevant. It should not be surprising then that a recent publication on Malaysia’s water policy and governance challenges was funded through an international body and not a Malaysian governmental agency (Tan, 2012).

1. Towards a Re-framing of Industry-University Collaborative Research in the Malaysian Water Sector

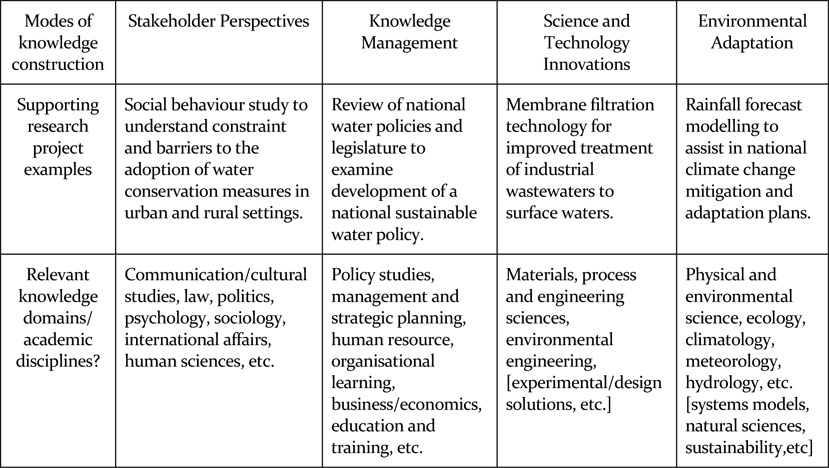

As indicated above, an integrated, optimal and sustainable approach to complex problems-solving represents the key to the Malaysian public policy goal of providing sufficient levels of clean water for domestic use. This will involve such an approach to a range of key factors. The interdisciplinary framework recommended here for future industry-university collaborative research provides a foundation for linking interdisciplinary academic collaboration to corresponding issues and challenges. This should include a focus on the following in particular: the public awareness challenge of getting people to better value water as a common resource (and avoiding wastage and also pollution by companies as well as individuals); an integrated human resource focus linking management and technical aspects of capacity-building; science and technology innovations to improve drainage, waste treatments, and piping; and how a changing urban demographic as well as climate patterns reflecting a changing as well as complex environment. Table 4 thus provides a sample outline of how the complex problem of water sustainability in the Malaysian context might be broken down in this way.

Distinct yet inter-related project examples of interdisciplinary university/R&D collaboration with the Malaysian water industry

The four examples of ‘supporting research projects’ outline how distinct yet interdependent modes of knowledge construction also frame multiple academic disciplines that might be harnessed in industry-university research collaboration. Just as a ‘complex problem’ approach might be broken down into interdependent yet distinct challenges and issues, so too supporting industry-based problems might be most usefully translated into relevant focus questions to depict multi-disciplinary applications for a convergent or interdisciplinary academic framework of collaborative research. Thus, the appendix Table outlines a comprehensively suggestive framework of the kind of interdisciplinary research questions corresponding which reflect a complex problem-solving approach to the thematic priorities identified in the seminar feedback session and represented in Table 3 above. It is a sample set of questions and not meant to be definitive. Also, whilst the generic framework has universal transferability, the particular configuration outlined here remains particular relevant to the local Malaysian context.

2. Towards an Interdisciplinary Focus for Industry Research Bodies

In order to harness the relative strengths of universities and to help fund projects across the four knowledge modes, a similar approach could be taken to the UK’s water industry. In 1993, the UK water industry established a research body called UK Water Industry Research (UKWIR). UKWIR provided a framework for the procurement of a common research programme for UK water operators on issues of common interest and need. UKWIR’s members comprise twenty-three water and sewerage undertakers in England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland and these all pay a yearly fee that covers the costs of the research projects (UKWIR, 2012). Industry-academic collaborations make up an important component of the research strategy as demonstrated by the presence of two national research councils, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) and the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) (UKWIR, 2012). Since UKWIR’s inception, universities and research institutions have supported numerous projects, including those as diverse the development of technology to minimise disruption during repair of water and sewerage systems (UKWIR, 2013) to quantifying ecosystem services at a catchment level (UKWIR,2013)

Such a research body could have offer a similar value to the Malaysian water industry where annual fees from stakeholders could be directed towards the pressing needs of the industry as a whole. This could be less focused on the more specialised sciences and engineering related projects which are already addressed through government research but encourage the kind of convergent and interdisciplinary connections and complex problem-solving discussed earlier. An existing industry association, the Malaysian Water Association (MWA), could be a useful vehicle in mobilising support whilst providing the institutional structure of the body. Indeed, one of its principle objectives is to promote research and development within the industry.

‘Innovation typically comes from the fringes of an organization and/or through the cross-pollination of ideas from different disciplines. We need to invite such thinking outside traditional silos and structures.’ - J.Cufaude (2010), ‘Break out of the silo mentality’,

This paper has explored how, in relation to the often complex challenges which confront the world a systems approach to integrated problem-solving lends itself to the natural policy nexus linking governments, the private sector (and commercial markets) and society at large within global as well as local contexts. The related link between an emerging paradigm of ‘science, technology and innovation’ and the challenge of achieving sustainable development suggests the future and critical ‘macro-stakeholder’ role also for universities and all related agencies of ‘research and development.’ This is in the context that universities also having an important role in reinforcing universal standards of critical rigor (i.e. which combine global as well as local convergences of accountability and feedback in various related senses and applications of these terms). The further related challenge of engaging with the ever-widening forces of complexity and change suggest the need for innovative as well as integrated problem-solving linking the domains of the human and natural sciences.

As evidenced above in relation to the Malaysian water industry, the crucial role of industry as well as other sustainable policy macro-stakeholders in optimizing as well as innovating sustainable and integrated human responses to a changing world is also usefully depicted in the ‘quadruple helix’ innovation theory models (e.g. Ofonso, Monteiro and Thompson, 2010). Such models typically focus on the need to convergently innovate (i.e. as economic growth) the distinct cultures of markets, bureaucracy/governance, academia and civil society. Whilst the innovation system model does often refer to ‘sustainable growth’ this is not strictly consistent with the basic definition of sustainability (especially when linked to a growing population and diminishing natural resources) as present local consumption to also meet the needs of a future world and global humanity. However, sustainability is also a crucial key to the global and long-term effectiveness of any local initiatives. In social-ecological systems theory the convergent resilience of communities and their habitats is viewed as an emergent internal-external adaptation response to complex environments (Berkes, Colding and Folke, 2003; Berkes and Ross, 2013). We extend this model to recognise how ‘internal’ notions of growth framed as adaption to changing ‘external’ environments can also be conceived as a relation of ‘dynamic equilibrium’ (Richards, 2013). And this should naturally apply to the interplay of complex human as well as natural systems.

In relation to how integrated methodologies and models of problem-solving and policy-building are needed to sustainably address and achieve designs solutions to ‘wicked problems’, this paper has especially explored in relation to the on-going Malaysian water crisis the related proposal that universities, academics and universal ‘research and development’ can and should take a more important and constructive future role in macro-stakeholder collaboration and convergent knowledge-building. Instead of mere data collection, decontextualized knowledge specialization, and descriptive linking of stakeholder perspectives, academics and researchers might better link macro and micro domains of knowledge and action (i.e. policies) in terms of a systems view of the future and not just the past. Thus, the future university has a pivotal role to play in the transition from the typically divergent past and present relation between the macro-stakeholders (or ‘quadruple helix’) towards a more convergent role in the future based on sustainability linking short-term and long-term interests as well as surface and deep modes of knowledge-building and macro and micro domains of policy-building. Our collaborative seminar with diverse industry participants from the Malaysian Water Association and beyond indicated that such a dialogical relation is not only possible, but also preferable and may even be crucial.