Proxy mobile IPv6 (PMIPv6) has been standardized by the NETLMN Working Group; it enables local network-based mobility management for meeting the needs of a heterogeneous handoff (HO) environment where client mobility can be performed without the use of another mobility management operation [1]. However, PMIPv6 cannot directly support global mobility and any specific authentication approach between different domains because it was originally designed for local mobility in a single domain. Because of these security issues, authentication is the fundamental security technology and has become the focus of security research [2].

Recently, some research has been conducted on the domain-level mobility of the PMIPv6 authentication method. This paper proposes secure pre-authentication and key management schemes for fast HO in PMIPv6. In addition to providing pre-authentication, the proposed authentication method can prevent threats such as replay attacks and key exposure. Further, analytic models have been used for measuring the authentication latency and for cost analysis. Then, the effects of mobility and traffic parameters on the authentication cost and latency, respectively, are analyzed.

In [3], Zhou et al. proposed a PMIPv6 authentication scheme based on diameter protocol, utilizing a pre-shared key between the AAA sever and the proxy mobile entities. They suggested that the interactions between the AAA sever and a proxy mobile entity can reduce the access efficiency. However, they do not mention sharing the key in advance. In [4], Zhang et al. proposed a certificateless signcryption scheme in the authentication process to solve the key management issue in a wireless environment during key negotiations with the AAA server, leading to an increase in the AAA server’s cost, and the scheme did not mention how to deal with handoff authentication. In [5], Gao et al. proposed an authentication scheme for PMIPv6 on the basis of a two-level identity-based signature scheme, which is a mutual access authentication protocol, for eliminating the interactions between the home network and an access network and thereby improving authentication efficiency and reducing cost. Nevertheless, their scheme is restricted to mobile access gateways (MAGs) in the same domain and does not consider a reduction in the authentication delay as in the case of the pre-authentication.

>

A. Authentication Architecture

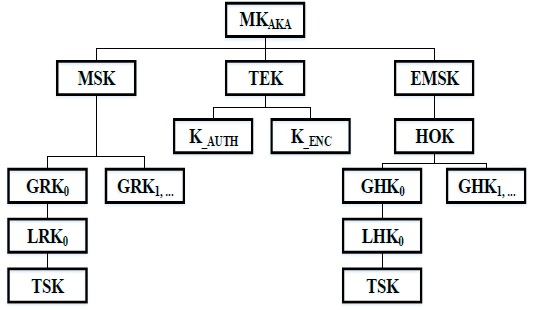

We use EAP-AKA, RADIUS, and the L2 triggers defined in IEEE 802.21 MIH for supporting a secure key distribution, mutual authentication, and inter-local mobility anchor (LMA) HO when a mobile node (MN) crosses the boundaries of a MAG within a PMIPv6 domain. We presume that the MAG and the LMA take charge of the authentication routine for a visiting MN. The AAA client is located at MAG and LMA. When the MN initiates a new session, the MN needs to be authenticated (i.e., initial authentication). In the standard EAP-AKA, the MN and the AAA must generate a master session key (MSK) and an extended MSK (EMSK) after successful authentication [6]. An MSK is delivered to the access point (AP) to be used in generating a transient session key (TSK). An EMSK is generated, but its use is not determined. We propose the use of an EMSK to derive additional keys in order to achieve secure pre-authentication without compromising security. We extend the key hierarchy in the EAP-AKA protocol by introducing MAG domain-level and local-level keys derived from the MSK and the EMSK as shown in Fig. 1. Globallevel keys are unique keys derived by the AAA and the MN for a PMIPv6 domain. Local-level keys are unique keys derived by the LMA and the MN for an AP within the MAG domain. Session keys are unique keys derived by the MAG and are later used for deriving TSKs. MSK is used for deriving additional keys for the MN’s re-authentication operations without HO. Further, we propose the use of the EMSK as the root key for HO pre-authentications.

The keys derived from the EMSK are the HO root key (HOK), the global-level HO key (GHK), and the local-level HO key (LHK). LHK is ultimately used for deriving TSK in intra- and inter-MAG HO.

>

B. Intra/Inter-LMA HO Authentication Procedure

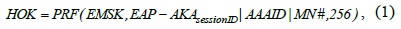

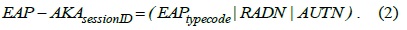

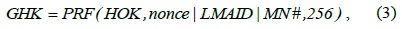

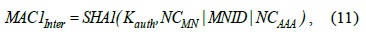

When an MN initiates a new session in a PMIPv6 domain, an authentication procedure is started. To derive the required additional keys, we suggest the following modifications to the EAP-AKA message flow as depicted in Fig. 2. After the EAK-APA protocol is successfully performed, six new keys are generated. The HOK, that is, the root HO key is derived from the EMSK by the AAA and the MN. Both nodes use a special pseudo random function (PRF) similar to the one used in generating the MSK in the standard EAP-AKA protocol.

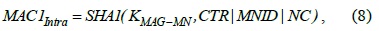

where “|” denotes concatenation and MN# represents the MN address in the medium access control layer. AAAID indicates the identity of the AAA server.

The global-level HO key, GHK, is derived from HOK by the AAA and the MN.

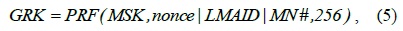

where LMAID and MAGID denote the identity.

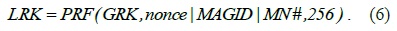

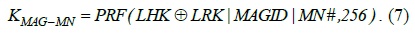

The global-level and local-level re-authentication keys, GRK and LRK, are derived from the MSK and the GRK by the AAA and the LMA, respectively.

A key used for securing traffic between the MN and the AAA,

Secure delivery of GRK, GHK and TMAGID is performed by the AAA to the LMA. Secure delivery of LRK is performed by LMA to the MAG. The derivation of HOK, GHK, LHK, GRK, LRK, and

>

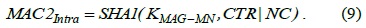

C. Intra/Inter-LMA Pre-authentication Procedure

An MN roams to a neighbor AP when experiencing the low signal intensity level of the current AP (CAP). The target AP (TAP) may be in the same LMA domain or belong to a different LMA domain. Because of the lack of an LMA HO authentication protocol in the PMIPv6 domain and the inadaptability of existing MIPv4/MIPv6 authentication protocols, we have designed intra and inter-LMA HO preauthentication protocols to minimize the authentication delay and the signaling overhead. The proposed protocols utilize the EAP-AKA messages and can efficiently operate in the PMIPv6 domain. The intra-LMA HO is locally carried out when the CAP and the TAP reside in the same LMA domain. Further, the inter-LMA HO is executed when the CAP and the TAP reside in different LMA domains. The intra/inter-LMA HO minimizes the dependency on the HSS and the HAAA to authenticate the MN and thus results in improved performance without compromising security.

The MN needs to supply the identities of the TAP and the TMAG that it requires to execute an HO to TAPID and TMAGID, respectively. Thus, we propose an adjustment of the IEEE 802.11 probe response management frames sent by the TAP to include its identity and the identity of the MAG associated with it as the information elements (IEs). A part of the IEs is set aside for future use and can be utilized for this purpose [7]. Do note that HO-related decisions such as HO triggers and the best TAP selection are out of the scope of this paper. Further, Fig. 3 depicts the inter-MAG HO authentication operation; here, the MAG controls the MN authentication instead of the HSS and the HAAA. The inter-MAG HO authentication protocol proceeds as follows:

The MAG also increments CTR and sends an EAP success message to the MN. Consequently, the MN derives LHK and increments CTR. CMAG and TMAG exchange a notify-request and notify-accept RADIUS AAA message to confirm the HO operation. Finally, LHK is sent to the TAP in the RADIUS access-accept messages with the MS-MPPE-Recv-Key attribute [8].

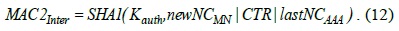

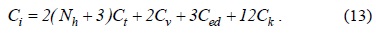

In the inter-LMA HO, the authentication procedure is completed without the need to retrieve security keys from the HSS, as shown in Fig. 4. The protocol procedure is as follows:

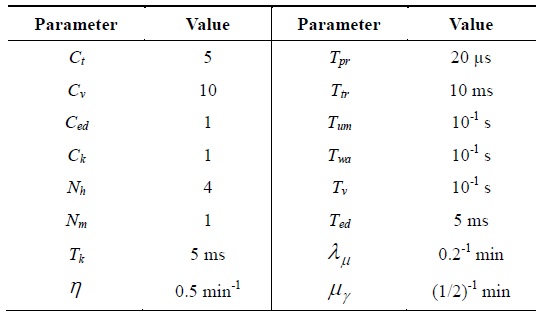

At the conclusion of a successful intra- or inter-LMA HO, a fresh LHK is retained by the MN and the TAP. The LHK is used for deriving TSK, which is then applied to generate additional keys that are demanded to secure the channel between the MN and the TAP.

>

A. Analysis of Average Authentication Cost

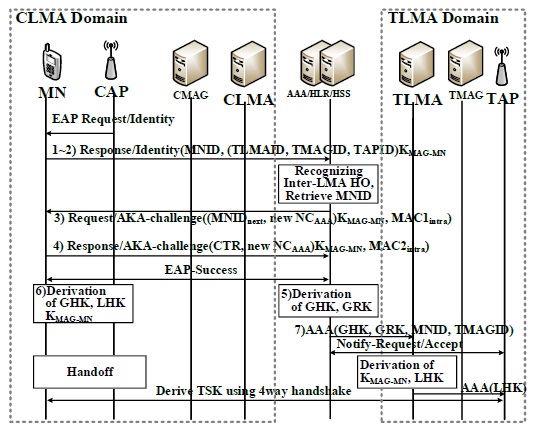

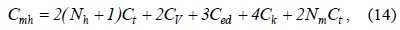

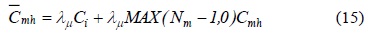

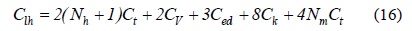

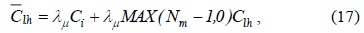

We define the authentication cost as the amount of signaling load and processing load during each authentication procedure. Then, the initial authentication cost,

where

where the last processing cost,

where

where the last processing cost, 4

where

>

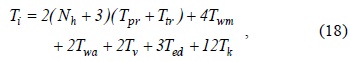

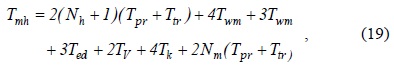

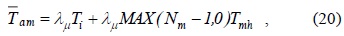

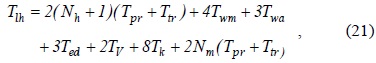

B. Analysis of Average Authentication Delay

We define authentication delay as the time from when an MN sends out an AR to when the MN receives the authentication reply (i.e., the EAP success message). Then, the delay per initial authentication,

where the time parameters

where the time parameter

where

where the time parameter

where

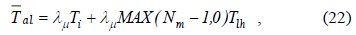

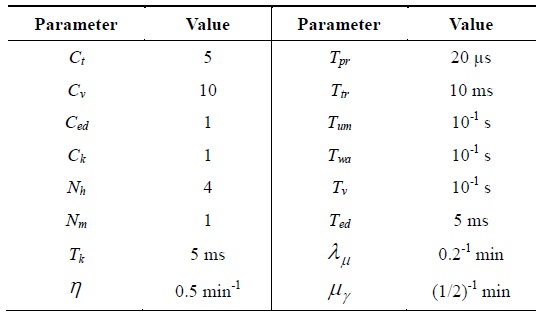

The parameters to evaluate the authentication cost and delay are shown in Table 1. Some parameter values for the analysis have been taken from [3]. The authentication cost in Eqs. (13), (14), and (16) can be calculated using the number of messages [10]. We utilize the ratio of the processing times to obtain the authentication cost because the time required to complete an operation represents the payload of the server to complete it [11]. The key generation cost,

[Table 1.] Parameters for evaluation

Parameters for evaluation

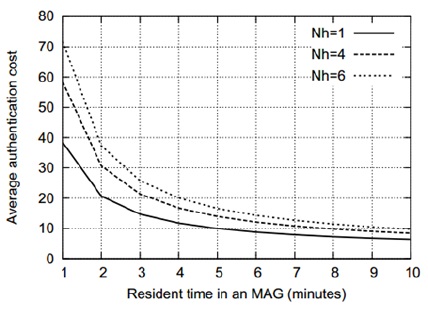

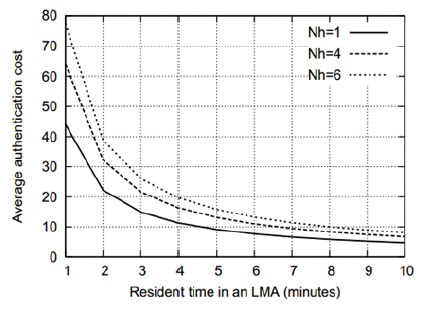

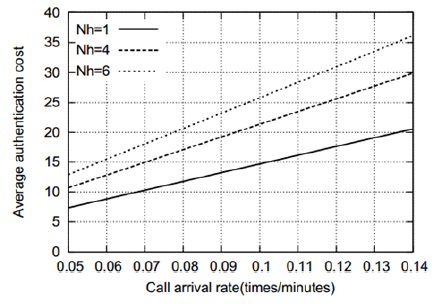

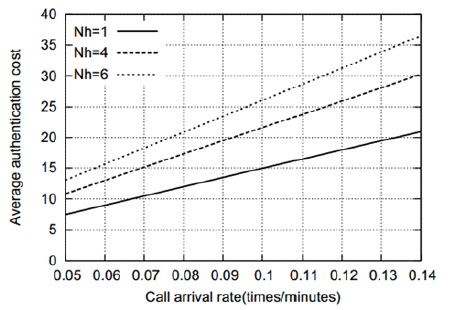

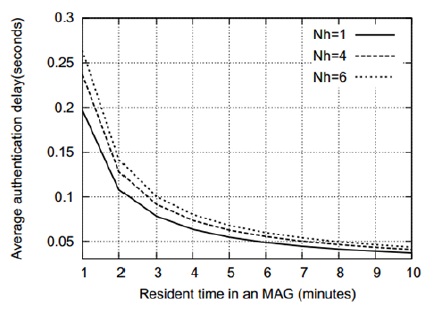

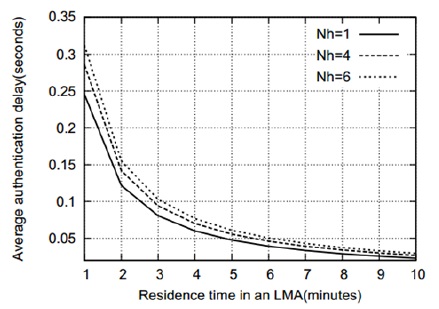

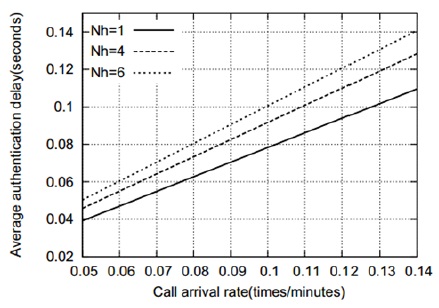

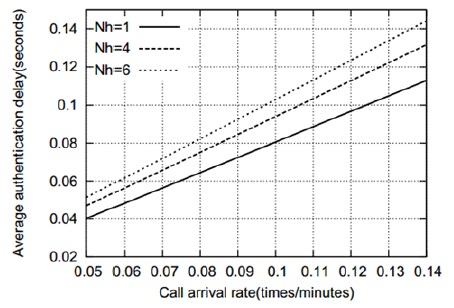

Figs. 5–8 show that the average authentication cost increases with an increase in the number of hops between the AAA servers. This is attributed to the fact that a relatively high transmission cost will be needed in such a case. Figs. 9 and 10 show the effect of the residence time on the average authentication delay. As we can see, the authentication delay decreases with an increase in the residence time of an MN in a MAG. As in the case of the authentication cost, this trend is attributed to the decrease in the handoff AR. Thus, if the residence time of an MN approaches infinity, the authentication delay will be the same as the initial authentication delay. In contrast, when the residence time approaches 0, most of the authentications are handoff authentications and the average authentication delay approaches infinity. However, for the sake of clarity, this is not shown in Figs. 9 and 10. Figs. 11 and 12 show that the average authentication delay increases with an increase in the call arrival rate of an MN. As shown in Eqs. (20) and (22), the authentication delay is proportional to the call arrival rate

In this paper, we proposed a pre-authentication method for the PMIPv6 protocol, which invokes the EAP-AKA signaling messages towards the AAA system. The proposed secure pre-authentication method prevents threats such as replay attacks and key exposure. We also conducted a performance analysis of the authentication cost and delay with respect to the mobility and traffic patterns. Therefore, this scheme presents a further understanding of the authentication mechanism in PMIPv6 networks. In the future, we plan to improve the proposed authentication method with a more detailed security analysis and better comparisons with other new authentication mechanisms in a PMIPv6-based network.