This study examines how the development level of the host country relative to that of the home country affects the performance of emerging economy MNEs’ overseas subsidiaries. Drawing from the social psychology literature on intergroup bias, we suggest that host country members’ nationalistic in-group bias against firms from a particular country tend to be stronger when the host country’s level of development is more advanced than that of the home country. Since nationalistic in-group bias causes various disadvantages to the subsidiary in terms of local marketing and internal management, we hypothesize that the host country’s relative level of development is negatively related to the subsidiary performance. Based on intergroup contact theory, we also hypothesize that the extent of expatriate deployment at the subsidiary will positively moderate the relationship between the host country’s relative development level and the subsidiary’s performance. Findings from our analysis of 1,453 subsidiaries of 818 Korean MNEs operating in 47 host countries provide support for our arguments.

본 연구는 본국 대비 현지국의 발전 수준이 한국 다국적기업 자회사의 성과에 미치는 영향을 살펴보았 다. 사회심리학이론의 집단 간 편향에 대한 기존 연구들에 기반을 두어 본 연구는 본국에 비해 현지국의 발전 수준이 높을수록 다국적기업에 대한 현지국 직원들의 국수주의적인 내집단 편향이 강하게 나타날 것이라고 주장하였다. 현지국 직원들의 국수주의적인 내집단 편향은 다국적기업 자회사에 부정적인 영향을 미치기 때문에 본국 대비 현지국의 발전 수준은 다국적기업 자회사의 성과에 부(-)의 영향을 미칠 것으로 가정하였다. 또한 집단 간 접촉이론에 기반을 두어 자회사의 주재원 활용 정도는 본국 대비 현지국의 발전 수준과 다국적기업 자회사 간의 관계를 정(+)의 방향으로 조절할 것이라고 가정하였다. 47개국에서 경영활동을 수행하고 있는 818개 한국 다국적기업의 1,453개 해외자회사들을 대상으로 이상의 주장들을 실증적으로 검증하였다.

International expansion of firms based on emerging economies has been an important trend during recent decades. Although firms based in the world’s most economically advanced regions, or the so-called “triad” regions (

Little empirical research, however, has been done to examine how the liabilities of origin affect the performance of the overseas subsidiaries of EE MNEs. Although the influence of home country context on a firm’s international competitiveness seems self-evident, given that the world’s largest and most successful MNEs are still predominantly composed of those from the most advanced economies, the question of how the host country context affects the performance of EE MNEs’ overseas subsidiaries has rarely been addressed.

The purpose of this study is to fill this research gap by exploring the relationship between the host country’s level of development relative to that of the home country and the performance of the EE MNEs’ foreign subsidiaries, along with the moderating role of home country expatriate staffing in that relationship. First, we address how the extent of disadvantages faced by firms from a particular country can be affected by the host country’s level of development relative to that of the home country and empirically examine the latter’s effect on the performance of the EE MNEs’ overseas subsidiaries. Drawing from the social psychology literature on intergroup bias, we suggest that host country members tend to hold nationalistic in-group bias that negatively affects their evaluation of and attitude toward foreign-affiliated firms and that such bias tends to be stronger when the host country’s level of economic or institutional development is more advanced than that of the home country. Given that nationalistic in-group bias or prejudice could cause various disadvantages in terms of evaluation of the MNE’s products or services in the host market, organizational identification by local employees, and the cross-border transfer of strategic organizational practices, we predict that the host country’s relative level of development would be negatively related to the performance of the MNE’s subsidiaries.

Second, in light of the research finding on the effectiveness of intergroup contact in reducing intergroup bias (Brown and Hewstone, 2005; Pettigrew, 1998; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2008), we also suggest that the deployment of home country expatriates to the subsidiary offers a potentially effective means to mitigate the liabilities of origin caused by the nationalistic in-group bias of the local employees at subsidiaries. Since expatriates act as a major channel through which contacts between the subsidiary’s local workforce and the headquarters’ management are promoted, they play a significant role in reducing the nationalistic in-group bias that local employees may harbor toward the home country management and thus contribute toward alleviating the disadvantages that stem from the biased perceptions and attitudes of the local employees toward the foreign management. Since this positive role of expatriates would be needed to a greater extent at those subsidiaries where the nationalistic in-group bias held by local employees is stronger, we predict a positive moderating role of the extent of expatriate deployment at the subsidiary on the negative relationship between the host country’s relative level of development and the subsidiary’s performance. We test these hypotheses on a sample of 1,453 subsidiaries of 818 Korean MNEs operating in 47 host countries.

Literature on intergroup bias and intergroup relations from the field of social psychology provides the theoretical bases underpinning the hypothesized relationship. In this section, we first discuss the effect of intergroup bias on host country members’ perceptions and attitudes toward foreign-affiliated firms, and how the difference in development levels between the host and home countries may affect such bias. We then discuss how disadvantages caused by host country members’ bias toward the firms from a particular country impact subsidiary performance. The role of expatriates in promoting the reduction of local employees’ bias toward the foreign management and mitigating the liabilities caused by such bias is discussed afterwards.

1. Relative Development Level of the Host Country and Liabilities of Origin

It has been well documented in the social psychology literature that people tend to hold ‘intergroup bias’, referring to the existence of “systematic tendency to evaluate one’s own membership group (the in-group) or its members more favorably than a non-membership group (the out-group) or its members” (Hewstone, Rubin and Willis, 2002: 576; for a more recent review, see Dovidio and Gaertner, 2010). According to social identity theory - an influential theory that accounts for the causes of intergroup bias - intergroup bias occurs due to the peoples’ basic motivation to achieve a positive self-concept (Tajfel and Turner, 1986). ‘Social identity’, defined as “a person’s definition of self in terms of social group membership” (Turner, 1999: 8), constitutes an important part of one’s self-concept. Since people strive to achieve positive self-concepts, they tend to be motivated to maintain positive social identity by evaluating their own groups more favorably than they do others.

In that nations constitute a basic social group, groupings based on national membership would be conducive to producing intergroup bias in evaluating the members of other nations. Nationalistic in-group bias, or the tendency to evaluate the members of one’s own nation more favorably than those of a foreign nation, will also affect the host country members’ perception and attitude toward the foreign-affiliated firms. In support of such a view, Newburry, Gardber and Belikin (2006) demonstrated that people indeed tend to evaluate foreign-affiliated firms as less attractive potential employers in comparison to domestic firms.

The strength of the nationalistic in-group bias that host country members hold toward a foreignaffiliated firm, however, may differ depending on the firm’s country of origin. We suggest that a perceived difference in status between the host and home country would affect the nationalistic in-group bias toward the foreign-affiliated firm, such that the bias would be stronger when the host country members in general perceive their country’s status as being higher than that of the home country. Such a view is based on the findings from the research on intergroup bias, which repeatedly demonstrates that the strength of intergroup bias tends to be affected by the group’s relative status. In general, intergroup bias has been found to be stronger when the perceived status of the in-group is higher than that of the out-group (for a meta-analytic review, see Bettencourt, Dorr, Charlton and Hume, 2001). Field studies conducted on multiethnic societies also report stronger prejudice against ethnic groups that are perceived to be lower in socio-economic status than one’s own group(Hagendoorn, 1995; Verkuyten and Kinket, 2000).

Countries differ in their levels of economic and institutional developments, and such differences are likely to shape peoples’ perception of their country’s status relative to that of other countries. The more advanced a country’s level of economic or institutional development, the more likely it is that the country’s members will perceive their national status as being higher than that of the other. Therefore, the more advanced the host country’s level of development in relation to that of the country from which an MNE originated, the stronger the nationalistic in-group bias will be that is held by host country members against the MNE’s local subsidiary. Since host country members’ discrimination against firms from a particular country constitutes an important source of the liabilities of origin, we posit that the disadvantages faced by MNEs in a given host market due to their national origin would be greater when the host country’s level of development is more advanced than that of the home country.

2. Liabilities of Origin and Subsidiary Performance

The MNE’s subsidiary may face various disadvantages as a result of the bias against firms from a particular country held by host country members both outside and inside the organization. On one hand, the nationalistic in-group bias will lead outside customers at the host market to evaluate unfavorably the products or services offered by the MNE’s subsidiary. On the other hand, disadvantages may also result from the nationalistic in-group bias held by the subsidiary’s local workforce. We argue that such bias by the local employees adversely affects the subsidiary’s local competitiveness through at least two attitudinal mechanisms: organizational identification and acceptance of strategic organizational practices transferred to the subsidiary.

Research indicates that local employees at foreign-affiliated firms tend to identify less strongly with their organization than employees at domestic firms do (Du and Choi, 2010). Referring to “the perception of oneness with or belongingness to” an organization (Ashforth and Mael, 1989: 21), organizational identification has been shown to have an impact on various work attitudes and behavioral outcomes, including motivation, organizational citizenship behavior, and job performance (Ashforth, Harrison and Corley, 2008; Pratt, 1998). As such, a lower level of organizational identification caused by the nationalistic in-group bias would lead to reduced levels of employees’ motivation and efforts to accomplish the organizational objectives, which in turn negatively impact the effectiveness of the MNE’s subsidiary and thus its competitiveness in the host country market.

We also expect that nationalistic in-group bias will increase the local employees’ reluctance or resistance toward accommodating the strategic organizational practices transferred from the foreign headquarters. ‘Strategic organizational practices’ refer to “those practices believed to reflect the core competencies of the firm and to provide a distinct source of competitive advantage that differentiates the firm from its competitors” (Kostova, 1999: 310). As such, successful transfer of such practices to the subsidiary would have an important impact on the subsidiary’s competitiveness in the host country. Successful cross-border transfer requires that the practices not only be implemented but also internalized by the subsidiary’s employees in the sense that they are “accepted and approved by employees” and “become part of the employees’ organizational identity” (Kostova, 1999: 311). Nationalistic in-group bias, however, would lead local employees to question the legitimacy and/or viability of the foreign organizational practices in the local environmental context, thereby reducing their motivation to accept and approve the practices.

Since nationalistic in-group bias against firms from a particular foreign country is expected to be positively associated with the development level of the host country relative to that of the home country, we suggest that the aforementioned disadvantages faced by the MNE’s subsidiary due to the host country nationalistic in-group bias would be greater when the host country’s level of development is more advanced than that of the home country. Prior research provides support for this view by demonstrating that the difference in development levels between the host and home country indeed has a significant influence on the local consumers’ product evaluation (Bilkey and Nes, 1982; Verlegh and Steenkamp, 1999), organizational identification by local employees, and the difficulties involved in cross-border transfer of organizational practices or knowledge (Edward and Ferner, 2004; Gupta and Govindarajan, 2000; Muller-Camen, Almond, Gunnigle, Quintanilla and Tempel, 2001; Smith and Meiksins, 1995). Since such disadvantages would adversely affect the organizational effectiveness and the competitiveness of the MNE’s subsidiary in the host country context. Furthermore, the findings of prior studies on Japanese MNEs’ subsidiaries indicate a negative association between expatriate ratio and subsidiary performance (Fang, Jiang, Makino and Beamish, 2010; Gaur, Delios and Singh, 2007). The following hypothesis is therefore proposed:

3. Moderating Role of Expatriate Utilization

Of the nationalistic in-group bias held by the host country members both outside and inside the MNE’s subsidiary, we argue that the bias held by organizational insiders cause disadvantages that are more primary and fundamental in their impact on the subsidiary’s local competitiveness. While the disadvantages caused by the nationalistic in-group bias of outside members, such as unfavorable evaluation of the MNE’s products or services, can be in part remedied by an effective marketing or public relations program, the effective design and implementation of such program will in no small part depend on the devotion and contributions of the local workforce. The bias against the foreign organization and management, however, would tend to limit their motivation to devote their efforts to protecting and pursuing the interests of the foreign organization.

Promoting intergroup contact between the subsidiary’s local employees and the home country management provides a potentially effective means through which reduction in nationalistic prejudice and improvement in attitudes toward the foreign management can be facilitated. Literature on intergroup bias and intergroup relations has repeatedly demonstrated the effectiveness of intergroup contact in bringing about a reduction of intergroup prejudice and improvement in intergroup attitude (for a meta-analytic review, see Pettigrew and Tropp, 2008). According to this literature, contact contributes to prejudice reduction through (1) enhancing knowledge about the out-group, (2) reducing intergroup anxiety that individuals often experience when encountering members of other social groups, and (3) enabling one to take the perspective of out-group members and empathize with their concern (Brown and Hewstone, 2005; Pettigrew, 1998; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2008).

Home country expatriates function as a primary channel for contact between the subsidiary’s local employees and the headquarters’ management. Consequently, the higher the number of expatriates deployed to the subsidiaries, the greater would be the opportunities for intergroup contact and the formation of intimate cross-national relationships. As the literature demonstrates, an increase in the quantity and quality of intergroup contacts helps reduce intergroup bias (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006). Therefore, the greater extent of expatriate deployment would be conducive to bringing about reductions in local employees’ nationalistic in-group bias toward the foreign management. The reduction in nationalistic in-group bias would in turn have a positive effect on local employees’ organizational identification and alleviate their resistance toward accepting and internalizing the foreign organizational practices that are of strategic importance. Expatriate deployment thus constitutes an effective strategy to mitigate the disadvantages caused by the nationalistic in-group bias of the local workforce. Since we expect such disadvantages to be greater when the development level of the host country is more advanced than that of the home country. Thus the following hypothesis is proposed:

Our sample consists of overseas subsidiaries of Korean MNEs. Information on these firms can be found in the 2008

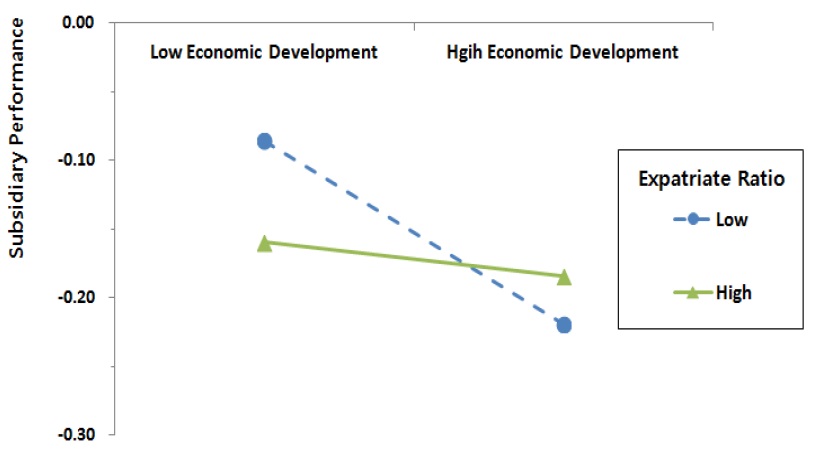

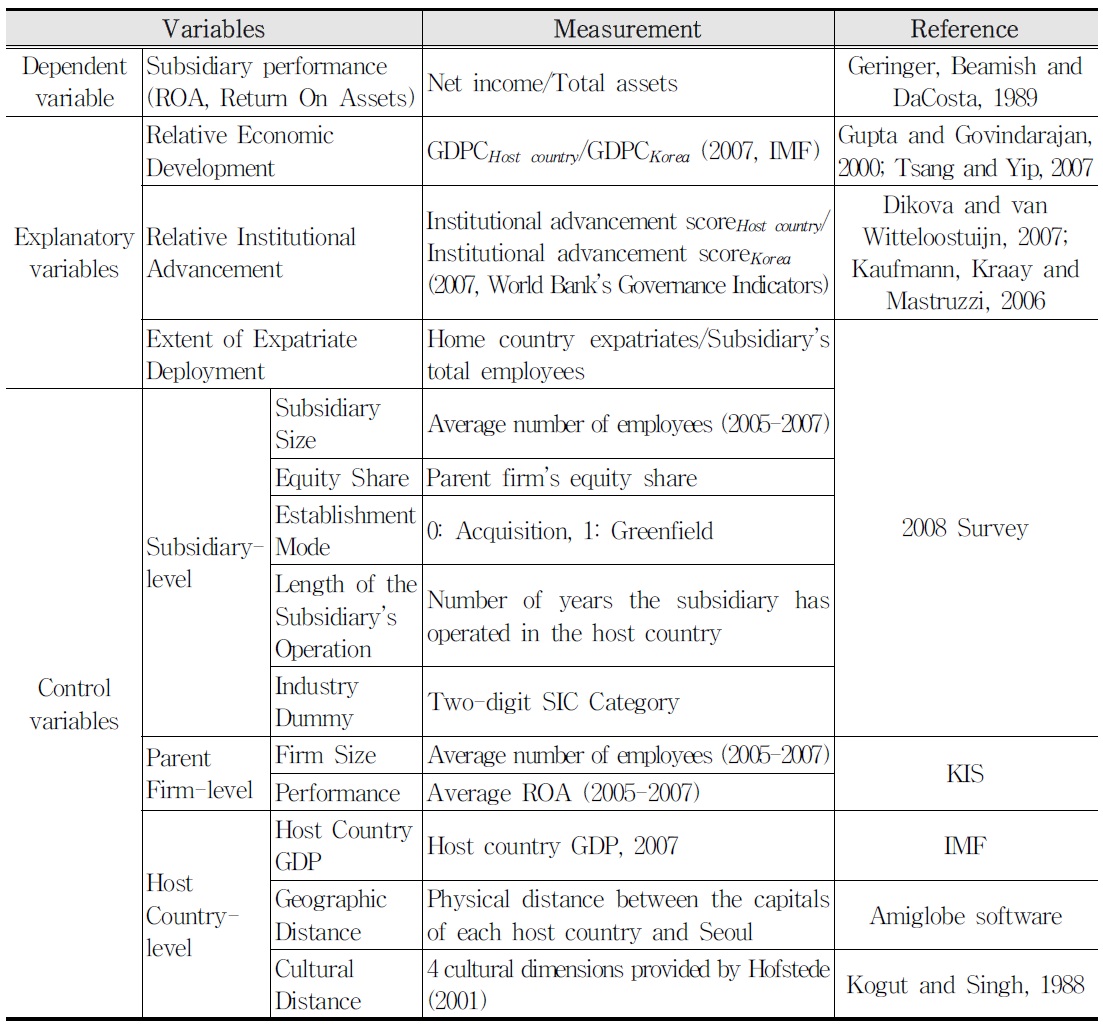

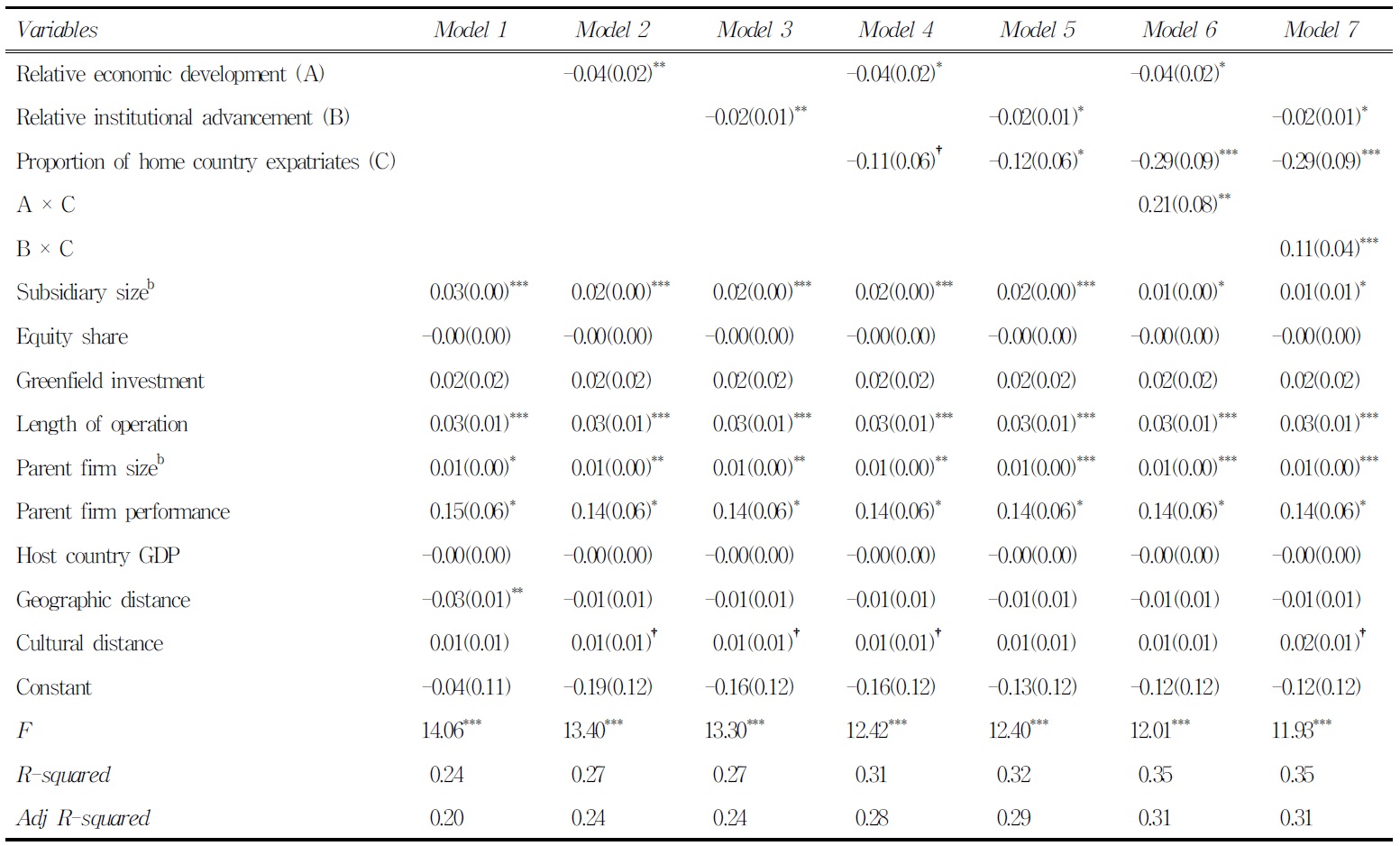

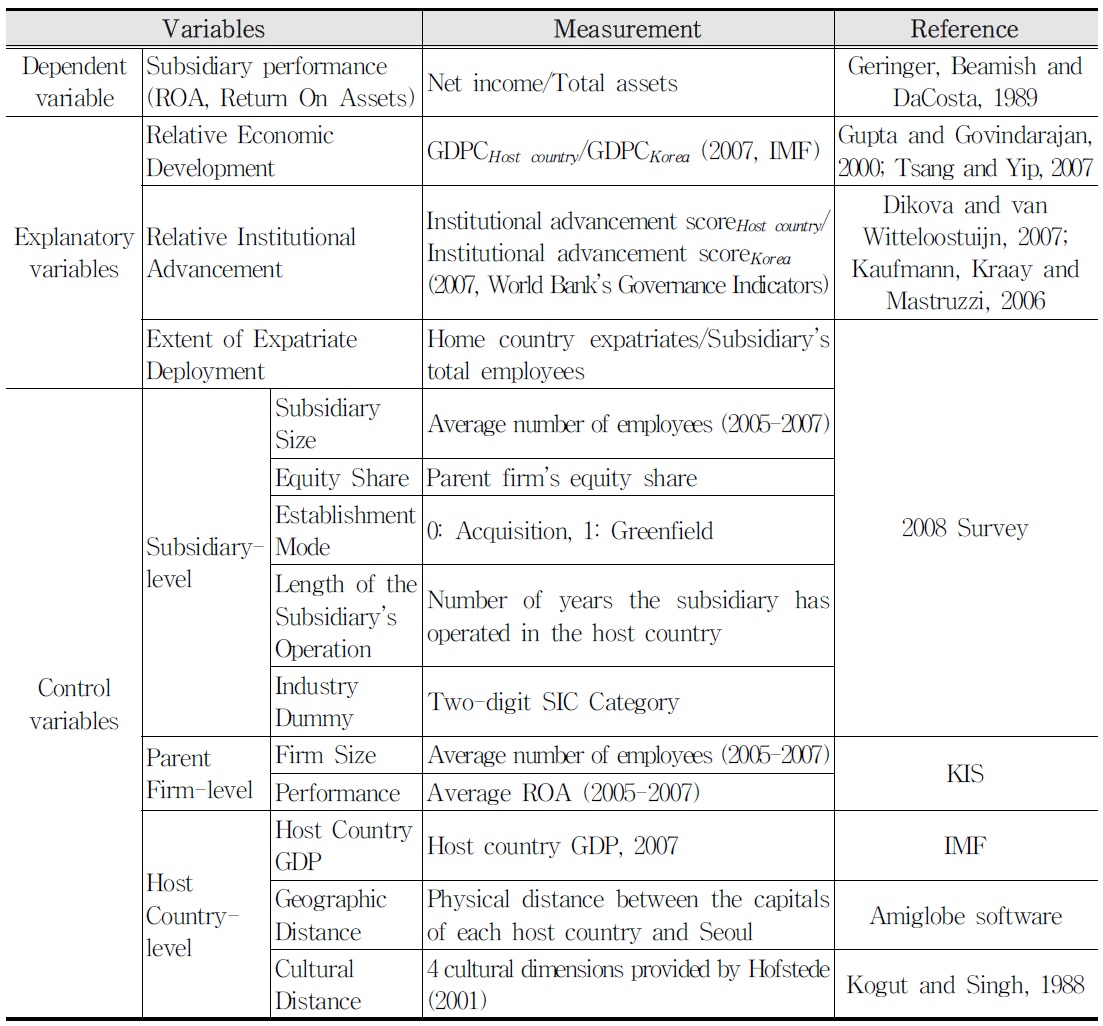

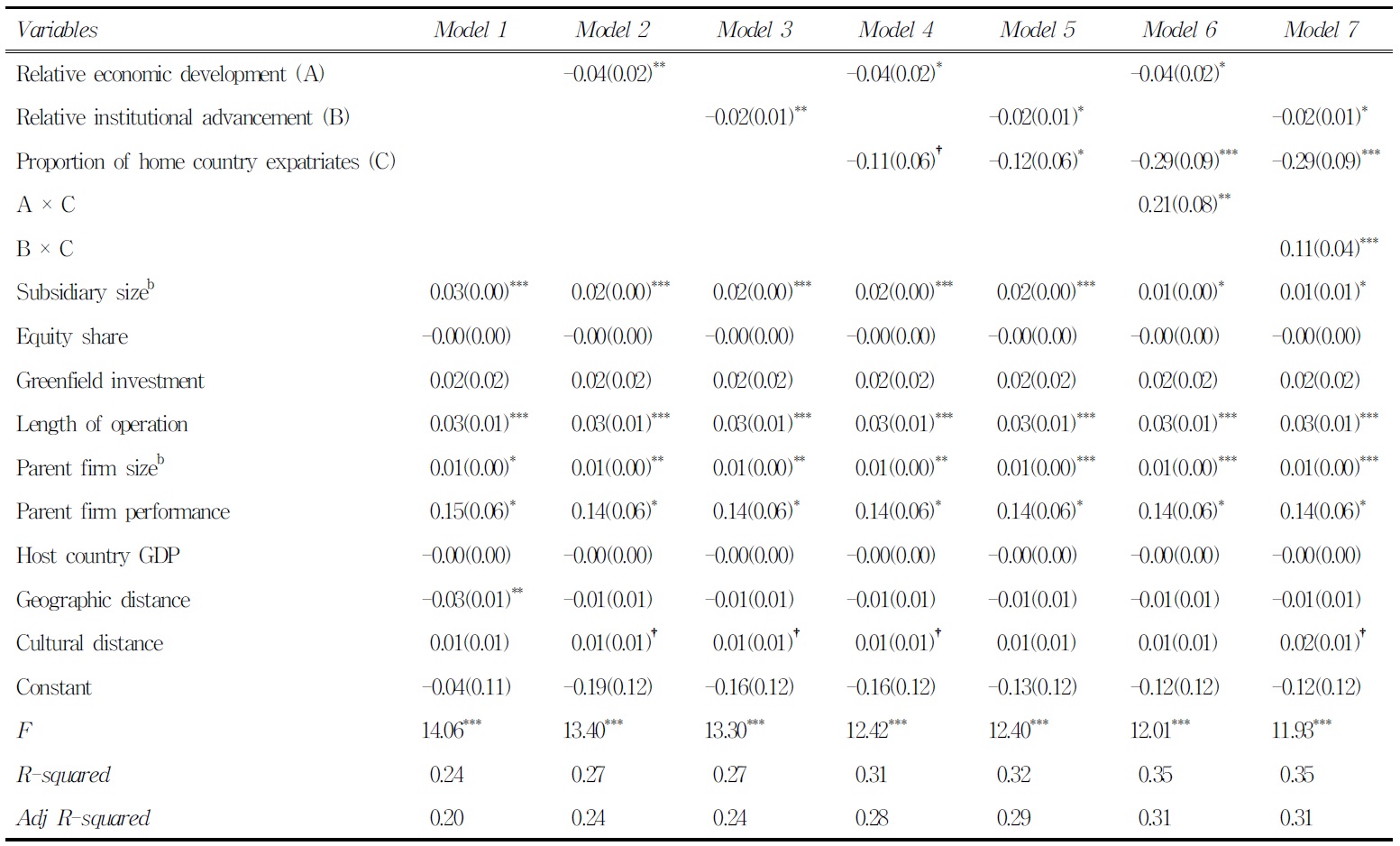

Measurement of the variables is described in Measurement Descriptive Statistics and Correlations (N=1,453)a Results of Regression Analysis on Subsidiary Performancea The coefficient estimates for the independent variables representing the relative economic and institutional development levels of the host country were negative and highly significant at the p<0.001 level in Models 2 through 7. Therefore, Hypothesis 1, which predicts a negative association between the host country’s relative development level and the performance of a foreign subsidiary, is supported. The coefficient estimate for interaction between the host country’s relative economic development level and the proportion of home country expatriates was positive and significant at the p<0.01 level in Model 6, while the coefficient estimate for interaction between relative institutional advancement level and the proportion of expatriates was positive and significant at the p<0.05 level in Model 7. Thus, the results support Hypothesis 2, which predicts the positive moderating role of the extent of expatriate deployment at the subsidiary on the negative association between the host country’s relative level of development and the subsidiary performance. A number of control variables have shown significant relationships with the dependent variable throughout the models. Among the subsidiary- level controls, the length of subsidiary’s operation in a host country shows positive associations with subsidiary performance at the significance level of p<0.001 throughout the models. Coefficient estimates of greenfield investment are positive but insignificant. Among the parent firm-level controls, both parent firm size and parent firm performance show positive association with subsidiary performance at the significance level of p<0.05 in all models. Among the countrylevel controls, coefficient estimates of geographic distance were negative and significant at the level of p<0.05 in all models. Coefficient estimates of host country GDP were also negative and significant at the p<0.05 level only in Models 3, 5, and 7, which included relative institutional advancement as a measure of host country’s relative development level. The differential effect of the host country’s relative development level on subsidiary performance for varying extents of expatriate utilization is depicted in This study examined the relationship between the host country’s relative development level and the performance of MNEs’ foreign subsidiaries and the moderating role of expatriate deployment in that relationship. Drawing from the literature on intergroup bias, this study suggests that nationalistic in-group bias in the perceptions and attitudes of a host country’s members against foreign-affiliated firms constitutes an important source of the liabilities faced by MNEs in a host country, and that such bias tends to be stronger when the host country’s level of development is more advanced than that of the home country. Since the bias against a foreign firm from a particular country is likely to have a negative impact on the firm’s competitiveness in the host country, we hypothesized that host country’s relative level of development would be negatively related to the performance of the MNE’s overseas subsidiary. The findings from the analyses of the performance of Korean MNEs’ overseas subsidiaries demonstrate the significant negative relationship between a host country’s development level and subsidiary performance. In addition, our results indicate that the use of expatriates positively moderates the negative relationship between host country development level and subsidiary performance. Interpreting this moderating effect from a different angle, we also found differential effects of expatriate utilization on subsidiary performance depending on the host country’s level of development. For less developed host countries, subsidiaries with lower levels of expatriate utilization showed better performance, while the opposite held true for more developed host countries. Under performance of subsidiaries with higher expatriate ratios in less developed host countries is consistent with the findings of prior studies on Japanese MNEs’ subsidiaries that indicate a negative association between expatriate ratio and subsidiary performance (Fang

Our findings extend previous research in several important ways. First, this study contributes to the literature on liabilities of foreignness by emphasizing how people’s innate bias or prejudice toward members of other social groups constitutes an important source of the liabilities faced by the MNE’s subsidiary in the host country. While previous studies have highlighted the more explicit sources of the liabilities of foreignness, such as unfamiliarity with the local environmental context, cultural or institutional incongruence, and discriminatory treatments by host country governments and organizations, this study emphasizes the importance of a more implicit source, namely, the inherent psychological tendency to evaluate individuals or organizations that are considered as members of an ‘out-group’ less favorably than those belonging to an ‘in-group.’ This study also highlights some of the important disadvantages arising from negative bias or prejudice toward firms from a particular country, such as lower level of organizational identification and greater difficulties of transferring practices and knowledge that are of strategic importance. Second, this study contributes to the literature on expatriate staffing by suggesting the important role of home country expatriates in promoting reductions in local employees’ prejudice toward the foreign management. This study’s findings also suggest that such a role played by the expatriates is likely to be more important in subsidiaries located in host countries that are significantly more advanced than the home country. Third, this study contributes to the literature on international business by demonstrating the significant impact of the host country’s relative development level on MNE’s foreign operations. While the literature on MNE has long recognized the important influence of the differences in host and home country environments on various aspects of international operations, most research has used distance variables, such as cultural distance or institutional distance, as a measure of the national difference. As Shenkar and colleagues (Shenkar, 2001; Shenkar, Luo and Yeheskel, 2008) point out, however, ‘distance’, by definition, connotes symmetry, such that the distance from point A to point B is identical to the distance from point B to point A. As such, the application of distance measures in the study of MNEs “conceals the different roles of the home and host environments,” and “diverts attention ... from relational properties such as the stereotypes held by members of one country toward another” (Shenkar This study suggests that not all liabilities faced by MNEs doing business abroad are uniformly imposed upon them. By identifying the sources of liabilities that affect MNEs operating in foreign countries to varying degrees, depending on their countries of origin, this study emphasizes the importance of the active management of the liabilities. While the more explicit and apparent parts of liabilities of foreignness are “always relative to the experience of the local firm” (Ramachandran and Pant, 2010: 238), the notion of liabilities of origin implies that a MNE, through its deliberate efforts, can reduce such liabilities more effectively than other competing MNEs. For instance, the efforts to enhance the home country’s cultural image among the people in the host country may mitigate, at least to a certain extent, disadvantages of the home country that are due to underdeveloped economic and institutional infrastructure. Diverse events that promote the home country’s unique culture and/or history may lead to a more holistic understanding of the home country among people in the host country, as the lack of understanding often leads to negative perceptions. While firm-level initiatives can take many actions, government agencies of the home country can play a significant role in improving the public image of the country, for the liabilities of origin by definition refer to legitimacy deficit that is largely external to the given firm. The MNEs could maximize the effectiveness of the efforts to enhance the image of their home country by securing the support of government agencies and aligning their own activities with such support. In such efforts, it is necessary to develop “a long-term virtuous cycle of coevolution” with the country image and the brand image (Ramachandran and Pant, 2010: 244). Given that the transfer of firm-specific advantages to subsidiaries typically relies on the use of expatriates from the home country, it has been widely recognized that expatriates to be dispatched should possess both businessrelated capabilities and ability to adapt to new foreign environment. Our findings further imply that it could also be critical for the expatriates to be equipped with keen understanding of their own culture as well as with the capability to actively communicate and promote it. Thus, training programs designed to enhance their understanding of the cultures of the home and host country would be useful.

This study’s hypothesis about the effects of the host country’s relative development level on subsidiary performance was based on the premise that the difference in development levels between the host and home country would significantly affect host country members’ attitudes and perceptions toward foreign firms. The premise, however plausible, was not directly tested, and therefore constitutes an important limitation of this study. As such it is pure conjecture whether the relationship is due to the alleged social psychological mechanisms or some other. What needs to be done is, obviously, to adequately deal with alternative explanations. One such explanation can be that companies originating in a country like Korea may find it hard(er) to compete in the most advanced markets due to a comparative lack of highly valued brands, and a history of low-priced (though good value) products. Another explanation can be that Korean companies even now experience a tough time entering advanced markets due to less access to distribution channels, localized resources, and lack of local networks. These alternative explanations also involve the moderating effect of expatriate deployment, since effectively dealing with such competitive disadvantages typically requires sending home country nationals to the those markets/locations. A valuable subject of a future study, therefore, would be the analyses of the influence of the difference in development levels between the host and home country on host country members’ attitudes and perceptions toward a foreign firm. A major challenge with cross-sectional studies on dynamic issues is that it is more or less impossible to treat the causal inference in a rigorous manner. So the relationship must be established theoretically. In other words, the possibility of endogenous variables in the model has to be checked. This issue should therefore be addressed both theoretically and statistically. In terms of empirical analysis, this study analyzed the foreign subsidiaries of MNEs from a single home country. Using a single home country sample thus limits the generalizability of this study’s findings. Future research that includes subsidiaries of MNEs from various emerging countries as a sample could test the robustness of this study’s findings and extend the arguments put forward in this study..

] Measurement

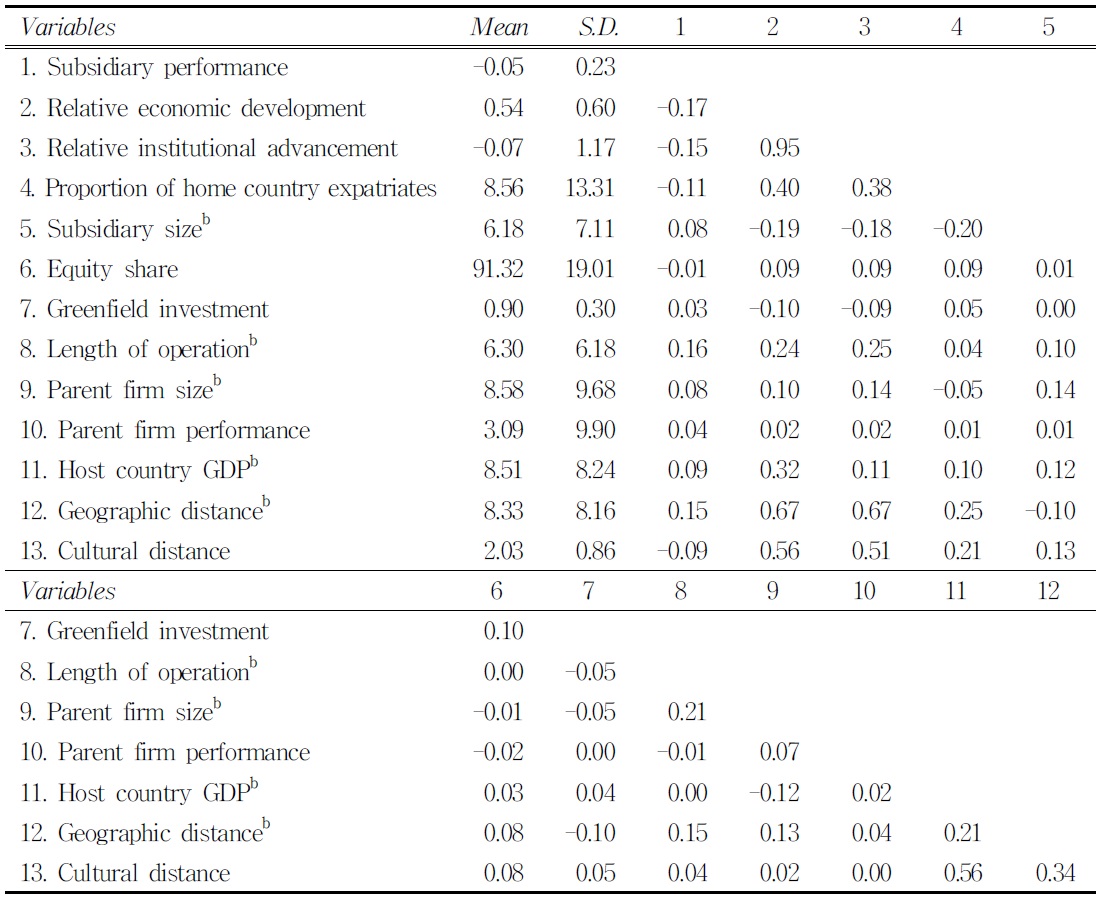

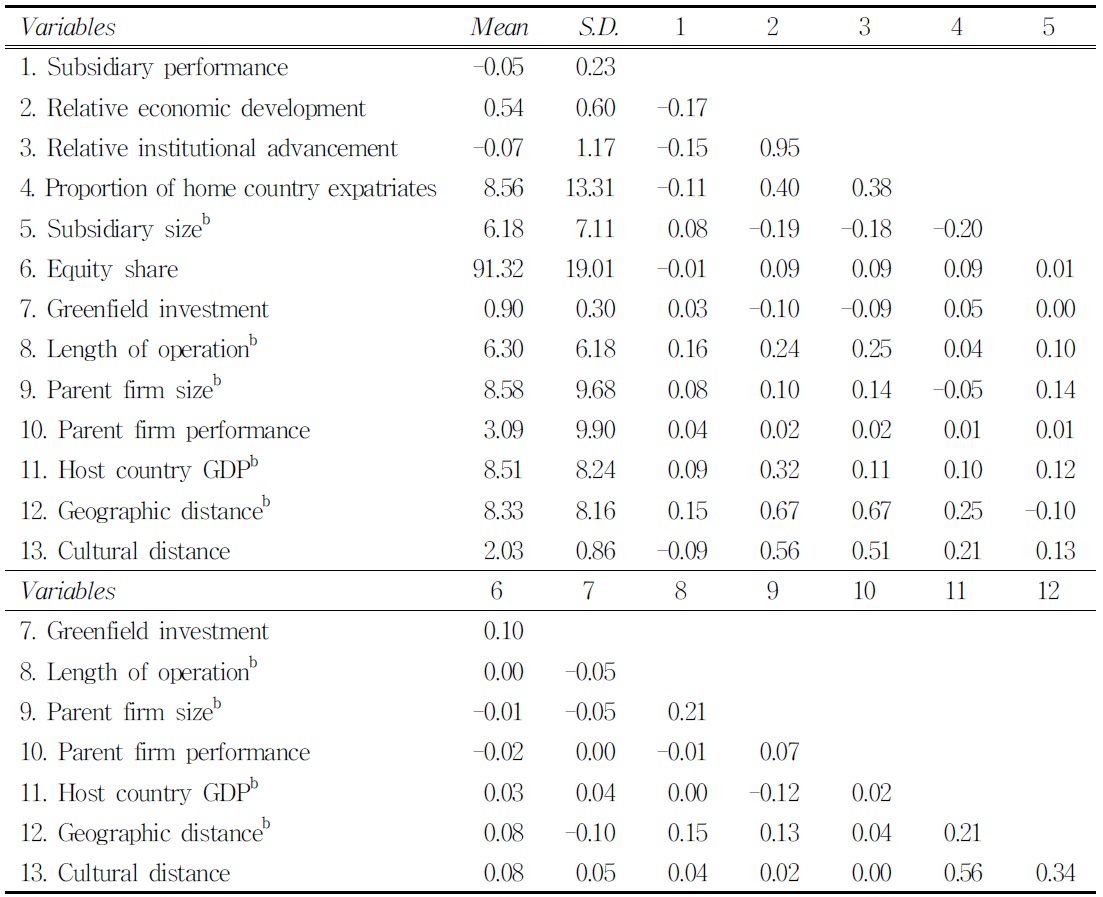

presents descriptive statistics and a correlation matrix for all of the variables included in the analyses except the industry dummies. We examined the potential for multicollinearity by inspecting the variance inflation factors (VIFs). Because we used per capita GDP and the institutional advancement scores of each country in separate models to avoid multicollinearity, the average VIFs for each regression model were all below 1.20. We thus concluded that multicollinearity does not threaten our parameter estimates.

] Descriptive Statistics and Correlations (N=1,453)a

presents the results of the ordinary least square (OLS) regression analysis, with the subsidiary performance as the dependent variable. Model 1 is a baseline model that includes only control variables. Two highly correlated independent variables used as measures of the host country’s relative development level - economic development and institutional advancement - were separately added to the baseline model in Models 2 and 3. Models 4 and 5 add the proportion of home country expatriates to Models 2 and 3, respectively. Models 6 and 7 are full models that include controls, each of the independent variables used as measures of host country’s relative development level, proportion of home country expatriates, and the interactions between each measure of host country’s development level and the proportion of home country expatriates in the subsidiary’s workforce.

] Results of Regression Analysis on Subsidiary Performancea

1. Contributions and Theoretical Implications

3. Limitations and Future Research

참고문헌

29.

Ramachandran J., Pant A.

(2010)

“The liabilities of origin: An emerging economy perspective on the costs of doing business abroad,” In T. M. Devinney, T. Pedersen & L. Tihanyi (Eds.), Advances in international management: The past, present, and future of international business & management

P.231-265

이미지 / 테이블

이미지 / 테이블

[

<Table 1>

]

Measurement

[

<Table 2>

]

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations (N=1,453)a

[

<Table 2>

]

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations (N=1,453)a

[

<Table 3>

]

Results of Regression Analysis on Subsidiary Performancea

[

<Table 3>

]

Results of Regression Analysis on Subsidiary Performancea

[

<Figure 1>

]

Moderating effect of the extent of expatriate utilization on the subsidiary performance

[

<Figure 1>

]

Moderating effect of the extent of expatriate utilization on the subsidiary performance