Gender representations in television advertisements have been a subject of academic research for many years (Eisend, 2010; Furnham & Paltzer, 2010). Most studies in this area have been conducted in the United States, beginning in the early 1970s (Dominick & Rauch, 1972; A. J. Silverstein & R. Silverstein, 1974). This was followed by U.S. studies in the 1980s (Bretl & Cantor, 1988; Caballero & Solomon, 1984; Ferrante, Haynes, & Kingsley, 1988; Lovdal, 1989), 1990s (Allan & Coltrane, 1996; Craig, 1992; Signorielli & McLeod, 1994), and 2000s (Bartsch, Burnett, Diller, & Rankin-Williams, 2000; Coltrane & Messineo, 2000; Fullerton & Kendrick, 2000; Ganahl, Prinsen, & Netzley, 2003; Stern & Mastro, 2004). Two decades after this type of research started in the United States, these studies were followed by some English-language studies on Asian countries, including Malaysia (Bresnahan, Inoue, Liu, & Nishida, 2001; Tan, Ling, & Theng, 2002; Wee, Choong, & Tambyah, 1995), Singapore (C. W. Lee, 2003; Siu & Au, 1997; Tan et al., 2002; Wee et al., 1995), Hong Kong and Indonesia (Furnham, Mak, & Tanidjojo, 2000). However, relatively few studies have examined gender representations in television advertising in Confucian societies (Arima, 2003; Bresnahan et al., 2001; K. Kim & Lowry, 2005; Siu & Au, 1997). This should be a particularly interesting arena for studies on gender, as Confucianism is based on a clear division between husband and wife (and, more generally, between male and female members of society). The former is the dominant partner and expected to show responsibility and benevolence to the latter, who is subordinate in the relationship and who should show obedience, loyalty, and respect (Hyun, 2001).

Korean society seems to be an especially interesting venue for gender research because scholars claim that the patriarchal Confucian philosophy has had an especially strong negative impact on women, and it has been blamed for both historical and contemporary gender discrimination. Although improvements have taken place in recent decades, e.g., in the form of increases in the access of women and girls to education and employment (K. Kim & Lowry, 2005), South Korean women still face large cultural disadvantages. This can be seen, for instance, in the results of Project GLOBE, a study of the differences in cultural patterns among 61 different cultures, in which South Korea scored the lowest in the category “gender egalitarianism” (House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, 2004). The Global Gender Gap Report of 2010 reported similar findings, in which South Korea was ranked number 104 out of 134 investigated countries. The report highlighted inter-gender wage differences in particular; women in South Korea earn 52% of the amount that men do. Furthermore, women make up a low percentage of legislators, and there is a relatively low level of enrollment of women at institutions of tertiary education (Hausmann, Tyson, & Zahidi, 2010). This study will analyze whether Korean television commercials reflect such gender inequalities and differences and what possible effects such representations might have.

Advertising not only reflects the social norms in a society (Frith & Mueller, 2010), but also teaches us about social roles and values (Pollay, 1986). Several theories support the argument of advertising shaping society. The most prominent one is social cognitive theory, which asserts that learning about the social environment can occur through direct as well as vicarious observation, such as watching television, including advertisements (Bandura, 2009). There are four processes to observational learning: attention, retention, production, and motivation (Bandura, 2009). One way to gain attention is through “attractiveness,”and television advertisements certainly show many physically attractive people (Stern & Mastro, 2004). Retention is the second essential process, since people can be influenced only if they remember what they see. One way to increase the likelihood of retention is repeated exposure (Smith & Granados, 2009), a trait of television advertising. The final processes are production (i.e., performing an act similar to that observed), and motivation. Motivation is influenced by the rewards associated with the modeled behavior. Generally, people are motivated by observing the successes of other people. Success stories are shown in most television advertisements. Boys eliminate their pimples and then can date the girls of their dreams; housewives are able to clean dirty clothes and are valued by their husbands. In general, people become more beautiful and attractive by using a specific product, and then they are rewarded with love, success, and admiration. Therefore, advertisements can be good motivators of behavior.

Most content analyses of gender representation use message effect theories as their rationale. The most widespread applied theories are social cognitive and cultivation theory; several studies also used agenda setting and priming, framing, and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions of masculinity (Neuendorf, 2010; Furnham & Palzer, 2010). Although the results of content analysis cannot claim to show any effects on audiences, content analysis is an important first step in understanding the possible impacts of media (Riffe, Lacy, & Fico, 2005).

Empirical research also supports social cognitive theory. A meta-analysis of previous studies confirmed that television teaches sex role stereotyping in children as well as adults (Oppliger, 2007). For example, watching stereotypical gender depictions in occupational settings lead to gender stereotypical job interests while the opposite can be reached with nontraditional portrayals (Smith & Granados, 2009). Research on advertising has also supported social cognitive theory (Garst & Bodenhausen, 1997; MacKay & Covell, 1997). For example, Garst and Bodenhausen (1997) found that men exposed to traditionally masculine portrayals in advertisements got more traditional attitudes. MacKay and Covell (1997) reported that male and female participants viewing sex image advertisements reported higher support for sexual aggression and showed less acceptance of feminism. They therefore concluded that such advertisements might undermine women’s striving for equality.

Gender Representations in Television Advertisements

A vast number of studies have investigated gender representations in television advertisements (Eisend, 2010; Furnham & Paltzer, 2010). Thus, in the following review, we focus mostly on research performed after 1995. It should be noted that much of the existing research is not perfectly comparable, even when variables seem similar on the surface. Differences may exist in cultural or national representation, sample size, the presence of unduplicated vs. duplicated advertisements, variable definitions, units of analysis (television advertisements vs. characters), and prime time vs. whole-day recording, because commercials played at different times of day might have different gender representations (Furnham & Voli, 1989).

This study investigates a range of variables with a long tradition of use in gender studies, including gender dominance, age, setting, voiceover, and product category. In addition, we have added variables that were not commonly used in previous studies on gender representations but that were regarded as essential for this study and highly recommendable for use in future research; these added variables include body type and the use of celebrities.

Representations of social groups in the media and in advertising are regarded as a way to portray their worth in society, which might influence what the audience learns about these groups (Gerbner, Gross, Signorielli, & Morgan, 1980; Lauzen & Dozier, 2005). In gender studies, gender dominance is analyzed by the ratio between the number of males and females involved. In the case of television advertisements, this type of analysis has led to mixed results. Whereas some studies showed a male dominance (Mazzella, Durkin, Cerim, & Buralli, 1992; Neto & Pinto, 1998), others showed a female dominance (Ibroscheva, 2007; Villegas, Lemanski, & Valdéz, 2010), and yet others found almost no difference (Milner & Higgs, 2004; Valls-Fernández & Martínez-Vicente, 2007). Also, in terms of the influence of time and geographical differences on gender dominance, no clear patterns were found. However, because a previous study of advertisements in South Korea found evidence for female dominance (K. Kim & Lowry, 2005), and because females are strong consumers in South Korea (T. Kim, 2003) and are therefore an interesting target group, we suggest the following hypothesis:

Another often-investigated variable is the age difference that is represented between genders. Based on the presented age differences between genders, the television audience can learn what is regarded as the ‘proper age’ for the respective gender. Previous studies led to similar findings: more females than males were found in the youngest age segment (under 35), whereas more males than females were found in the middle (35-49) and oldest age segments (50+). We could not find any exceptions to the first findings, but there were a few exceptions to the second (Fullerton & Kendrick, 2000; Milner & Higgs, 2004) and third findings (for New Zealand: Furnham & Farragher, 2000; Valls-Fernández & Martínez-Vicente, 2007). This age imbalance between males and females is called the “double standard of aging,” reflecting a society that is much more permissive of aging in males than in females (Sontag, 1997). In other words, appearance is an important asset for women and younger means prettier in most societies, while for men experience and authority are more valuable, assets that are developed with age. Based on previous research, we propose the following hypotheses:

South Korean television commercials employ a high number of celebrities. Choi, Lee, and Kim (2005) reported that 57% of all television advertisements included celebrities, and Praet (2009) found that 61.1% of the people appearing in commercials were celebrities. Under these circumstances, we found it essential to analyze the variable of celebrity in relation to gender and other variables, since differences between celebrity and non-celebrity characters might appear. In addition, we wanted to investigate if celebrities are associated with a respective gender, since this might show, e.g., that females are underrepresented within the non-celebrity group while otherwise this is not the case. Choi et al. (2005) reported more male (55.6%) than female (44.4%) celebrities in South Korean television commercials; and thus, we state hypothesis 3 in the following way:

A few studies have investigated the body types of males and females appearing in advertisements. This is an important question in a time when an increasing number of individuals, especially females, are reported to suffer from eating disorders, which some studies have linked to media influences (Levine & Harrison, 2009). Signorielli and McLeod (1994) found that in television advertisements females were more likely than males to have very fit bodies: around three quarters of females had such bodies, whereas the same proportion of males had average sized bodies. Stern and Mastro (2004) found that female children and young adult women were the slimmest within the female group, whereas only male children were similarly slim. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

In the existing literature, setting is a variable that largely produced highly stereotypical results and clear gender divisions. From such representations, audiences learn the places (associated with typical actions in those places) where a particular gender is expected to be. Such depictions of males and females may teach and reinforce the viewer’s gender-typed occupational schemas. Research in the United States even has indicated that watching stereotypical advertisements leads to less interest in jobs traditionally associated with the opposite gender, while viewing females in nontraditional occupations can increase the acceptability of females working in nonconventional careers (Smith & Granados, 2009). Most studies reported more females to be shown at home. Very few studies reported different results, including Furnham et al. (2000), who found slightly more males than females shown at home in Hong Kong, and Breshnahan et al. (2001), who found the same percentage of males and females shown inside the home in Taiwan. Another finding that was similar across most of the literature is that more males than females are shown in a workplace setting (Ibroscheva, 2007; Uray & Burnaz, 2003) and in an outdoor setting. For example, this finding was reported in studies from Australia (Milner & Higgs, 2004) and Saudi Arabia (Nassif & Gunter, 2008). Based on these findings, we suggest the following hypotheses:

One of the most consistent findings in terms of gender representation in television advertisements has been the predominance of male voiceovers (Furnham & Mak, 1999). In the context of the United States, Bretl and Cantor interpreted the dominance of male voiceovers as representing the “voice of authority” (Bretl & Cantor, 1988, p. 605). Thus, the gender of the voiceover reminds the audience who the authority within a society is. We could not find any studies since the 1970s in which this finding was not supported. In addition, Uray and Burnaz (2003) found that when the primary character is a male, mostly male voiceovers are used, whereas when the primary character is a female, both male and female voiceovers are used. The authors proposed that male voiceovers reinforce the credibility of the female primary character. Because no study was found that showed a majority of female voiceovers, we propose the following hypothesis:

The product categories used by different genders are often analyzed to see whether the products are associated with the respective genders and to what degree these associations limit gender portrayals. However, there are relatively few consistent findings in terms of product categories associated with a specific gender; this may be because different studies often employed different product categories. One finding that was true in most studies was the association between females and body products, or as other studies called them, “toiletries,” “beauty products,” and “personal care products.” The strong association between females and cosmetics/toiletries products emphasizes the importance society assigns to females’ beauty and contributes to their sexualization (Luyt, 2011). The association between females and cosmetics/toiletries products was proven to be true in the United States (Ganahl et al., 2003), Mexico (Villegas et al., 2010), Spain (Royo-Vela, Aldas-Manzano, Küster, & Vila, 2008; Valls-Fernández & Martínez-Vicente, 2007), Turkey (Uray & Burnaz, 2003), Saudi Arabia (Nassif & Gunter, 2008), Singapore (Tan et al., 2002), Indonesia (Furnham, et al., 2000), Malaysia (Bresnahan et al., 2001; Tan et al., 2002), Japan and Taiwan (Bresnahan et al., 2001), and Great Britain and New Zealand (Furnham & Farragher, 2000). Fewer studies associated females with household and cleaning products (Nassif & Gunter, 2008; Royo-Vela et al., 2008; Tan et al., 2002). For males, product associations were less clear. Some studies found associations between males and television advertisements for cars (Furnham et al., 2000; Ganahl et al., 2003; Royo-Vela et al., 2008; Tan et al., 2002; Valls-Fernández & Martínez-Vicente, 2007) and telecommunications, electronics, technology, and computers (Bresnahan et al., 2001; Ganahl et al., 2003; Royo-Vela et al., 2008; Tan et al., 2002). Thus we formulate our last hypothesis as follows:

The recording of the sample took place in Chuncheon, South Korea, during the week of October 19-25, 2009. Of the five major terrestrial television networks in South Korea, three were selected (MBC, GTB/SBS, and KBS) because they all broadcast advertisements and have the highest market share, each more than 10%, while cable channels have market shares of 2% or less (WARC, 2012). Recordings were made during prime time, which is referred to as Super A (SA) in South Korea. Super A includes the time period from 8:00 p.m. to 11:00 p.m. on weekdays and from 7:00 p.m. to 11:00 p.m. on weekends (KOBACO, 2006). From a theoretical point of view, the commercials in these channels are the ones most watched and presumably the ones most learned from. To represent all three channels, the total recording time was divided into one-hour blocks, and television channels were randomly assigned to one-hour time slots and rotated (see also B.-K. Lee, Kim, & Han, 2006; Zhang, Song, & Carver, 2008). Local advertisements, political campaign advertisements, self-promotional advertisements for the networks/television programs, advertisements for entertainment products (such as movies, music concerts, DVDs, CDs), advertisements for festivals and events, and public service announcements were not included in our sample (Bartsch et al., 2000; K. Kim & Lowry, 2005; Villegas et al., 2010). This yielded 415 commercials of which 322 commercials included primary characters, and this group served as our primary sample. We did not control for duplication because this represents the reality of television viewing (Roy & Harwood, 1997; Zhang et al., 2008). Moreover, the preservation of duplicates is also in line with social cognitive theory, in that repeated exposure might “function as a form of cognitive rehearsal, thereby strengthening sex-typed scripts in memory” (Smith & Granados, 2009, p. 349).

Our unit of analysis was the primary character. We analyzed whether there was a primary character in the advertisements and identified the gender of the primary character (0 = none, 1 = male, 2 = female). A primary character was defined as a person aged 18 or older who appeared on camera either with a speaking role or with prominent exposure for at least 3 seconds. The character must be clearly visible (most commonly through a medium camera shot or a medium long shot), especially his or her face, and the character must appear clearly enough for age and gender to be coded. When several characters appeared in a commercial, we followed the rules used in the existing literature to identify the primary character (Nassif & Gunter, 2008). The coders selected the primary character as the one who (1) provides substantial information about the advertised product or service, (2) uses or holds the product, (3) speaks longest, (4) appears longest, (5) appears in a close-up longest, and/or (6) appears in the center of the story or the shot (in this particular order of decision criteria). Commercials without primary characters were not further analyzed in this study.

Two South Korean students (one male and one female) were trained for 10 hours on a separate sample. After they reached a sufficient intercoder reliability, they started coding the entire sample independently. Intercoder reliability coefficients, as measured by Cohen’s kappa, ranged between .62 for body type and .93 for product category, and thus above .60 for all variables, and therefore were sufficient (Neuendorf, 2011). Disagreements among the coders were resolved through discussion to reach a final data set.

Age. A character’s age was estimated as being (1) 18-34, (2) 35-49, or (3) 50 years or older. Factors that aided in this judgment included the following (Simcock & Sudbury, 2006) : (1) the character’s age is known (i.e., a celebrity); (2) there are references to age in the advertisement; (3) the physical appearance of the character indicates the age (e.g., graying/thinning hair, wrinkles).

Celebrity. The primary character was coded to be (1) a non-celebrity or (2) a celebrity. A celebrity is a person who is recognized in a society or culture, including, for example, actors, singers/musicians, athletes, and TV personalities. Coders had to know the name of the celebrity in order for him/her to be counted as a celebrity.

Body Type. The body type of the primary character was categorized as (1) thin, (2) average, or (3) obese and/or out of shape.

Setting. The place where the primary character predominantly appeared was categorized as (1) a workplace (inside), (2) a home (inside residential space), (3) other indoor settings (e.g., store, restaurant), (4) outdoors, or (5) other (e.g., artificial background).

Voiceover. Voiceovers were categorized as (1) no voiceover, (2) male voiceover, (3) female voiceover, or (4) male and female voiceover. Voiceover refers only to the voices of people who cannot be seen throughout the commercial in any of the camera shots. Specifically, voiceovers are defined as messages spoken by an off-camera speaker during a commercial. A voiceover does not include the following: (1) the thoughts of people who appear in the advertisement; (2) voices that are heard only singing; (3) voices of children; (4) a product slogan or company name spoken at the end of a commercial.

Product Category. Based on the results of a pilot test, 16 product categories were investigated: (1) foods/snacks, (2) non-alcoholic drinks, (3) alcoholic drinks, (4) cosmetics/toiletries, (5) pharmaceutical/health products, (6) cleaning products/kitchenware, (7) household appliances, (8) home entertainment, (9) real estate/housing, (10) automotive/transportation, (11) finance/insurance/legal, (12) restaurants/retail outlets, (13) fashion/accessories, (14) mobile phones/providers, and (15) computer/ communications (not including mobile phones). All other product categories, such as travel/vacation, toys/games, etc., were categorized as (16) other, since they rarely appeared during the pilot test and in the coding of our sample.

The final sample of South Korean television advertisements included 322 primary characters, of which 58.1% (

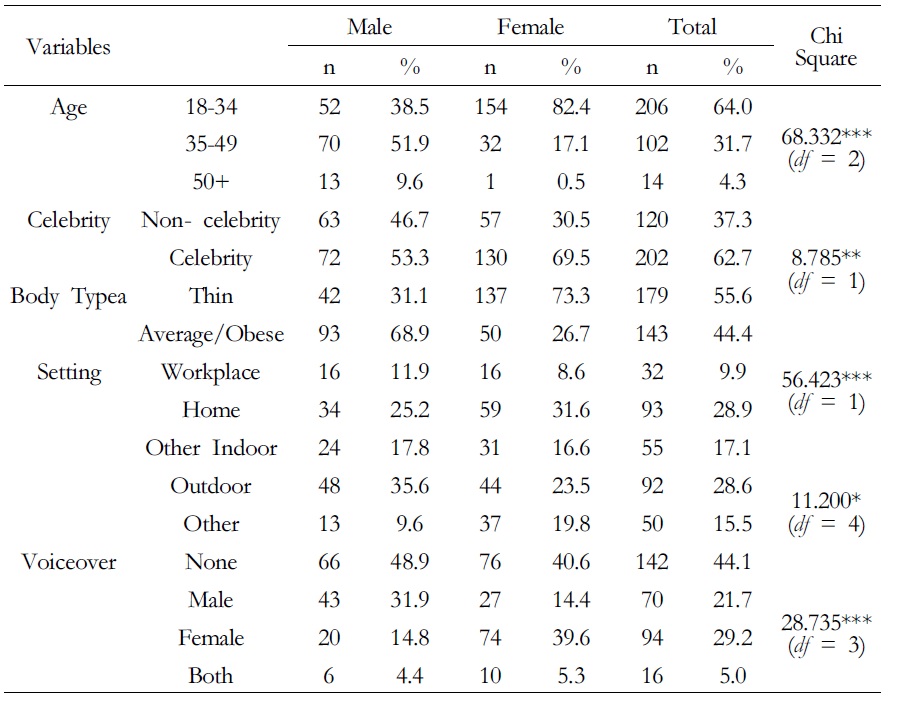

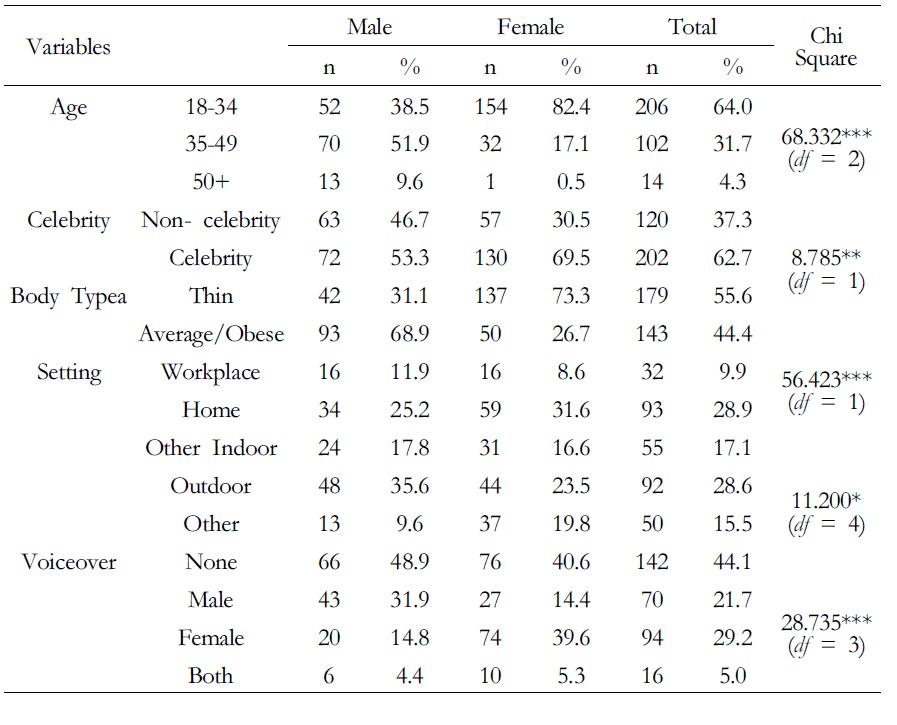

In terms of the age of the primary characters (see Table 1), there was a significant difference between the two genders (

[Table 1.] Relationships between gender and different variables

Relationships between gender and different variables

We found more celebrities than non-celebrities for both genders. Celebrities represented 53.3% of males and 69.5% of females; overall, 62.7% of all primary characters were celebrities. In addition, we found a relationship between the gender of the primary character and the celebrity/ non-celebrity variable (

The importance of celebrities as a control variable for this research can be seen when looking at the age variable. Among the male non-celebrities, 61.9% (n = 39) were young, and 38.1% (

The body types displayed for primary characters were differentiated by gender (

As in the case of age, the results regarding body types were strongly influenced by the presence of celebrities. Whereas there was no significant difference between male and female body types among the non-celebrities, who were mostly shown with average bodies (

For the settings variable, we found a significant difference between genders (

Overall, there were more female (29.2%;

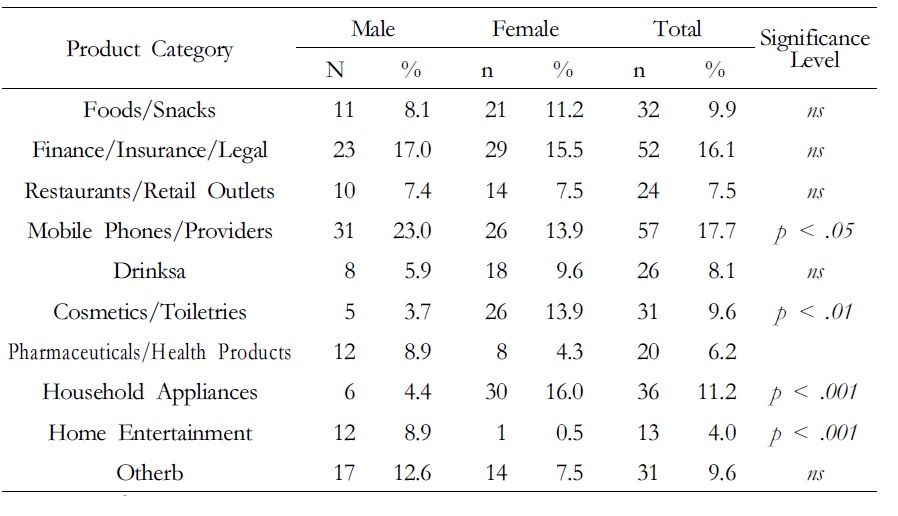

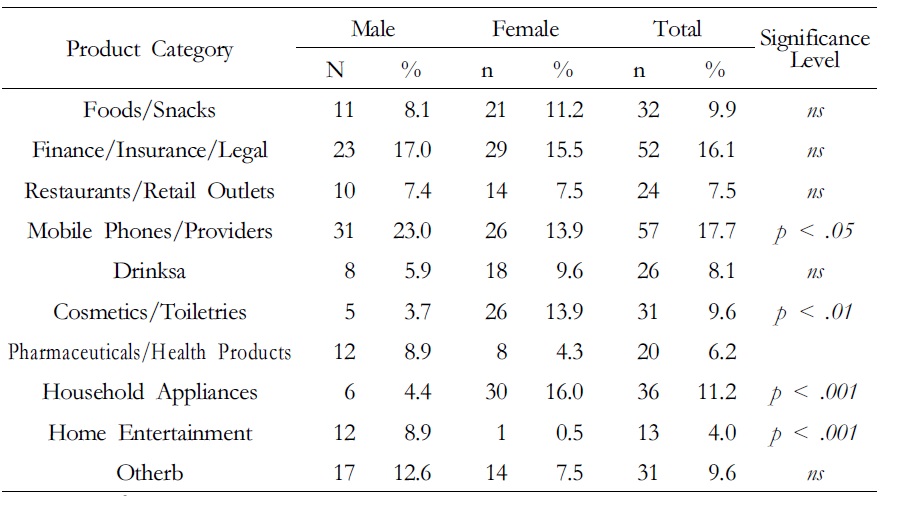

[Table 2.] Relationships between gender and product category

Relationships between gender and product category

As shown in Table 2, different product categories were associated with different genders (

The analysis of gender representations in South Korean prime time television advertisements yielded stereotypical and counter-stereotypical results. Some areas were still very much in accordance with stereotypical gender representations, as delineated in previous research. These representations included the dominance of females in the younger age segment as well as females being predominantly portrayed with thin bodies. However, it should be noted that both findings were true mainly for celebrities, a category in which females also predominated. Finally, we confirmed some product categories that were associated with males and females: females were shown with cosmetics/toiletries and household appliances, whereas males were shown with electronic products, such as mobile phones/providers and home entertainment.

In contrast to these stereotypical representations, which were in line with previous research, there were also some counter-stereotypes. Considering that numerical representations are often seen as an indicator of the importance and relevance of a social group (Gerbner et al., 1980), it is an important finding that more females than males were found in South Korean television commercials. This finding counters research from many other countries as well as the expectations of representations in a Confucian society, where males have traditionally dominated (Hyun, 2001). However, one must question whether this truly represents female importance and relevance and whether this is a positive result. In the case of females in South Korean television advertisements, this would mean that young, thin females are most relevant. In addition, there might be other reasons for the dominance of females, such as that programs are geared more toward a female audience, which can be seen in the fact that women clearly watch more TV than men in South Korea, even during prime time (KOBACO, 2006). Another reason might be that a male-dominated society wants to “gaze” (Mulvey, 1975) more at young females than at males. In the context of television dramas, Gerbner et al. (1980, p. 40) wrote, “the character population is structured to provide a relative abundance of younger women for older men,” a pattern that also seems to hold true in the context of television advertisements in patriarchal South Korea even many years later.

Two representations that clearly ran against the global trend were the settings and voiceovers used. We could not find any significant differences between the genders being shown at home or at the workplace; this is in stark contrast to nearly all previous studies. The only significant difference found was that more males were shown outside; however, this variable also loses interpretive potential when females are not shown at home. As a result, the results for settings clearly ran against a traditional representation of gender. One reason for this might be an increase in female labor participation within South Korean society, from 37% in 1963 to more than 50% nowadays (B. S. Lee, Jang, & Sarkar, 2008), indicating that Korea no longer reflects the labor division of a Confucian society. However, the female labor force still is rather small and there are many areas of employment in which females are underrepresented (Hausmann et al., 2010). This clearly shows a strong gender division in the labor force in Korea and shows that South Korea is still a heavily patriarchal society with a clear gender division of power. Nevertheless, women are increasingly well educated and starting to play more important roles within companies. A more valid explanation for a nearly equal gender representation at home and in the workplace might be that Korean women are an important target group as the main audience during prime time, and television advertisers want to sell at least the dream of a workplace with equal chances.

Lastly, the use of voiceovers in South Korean television advertisements is probably the most striking finding. We could not find a predominance of male voiceovers; there was actually a higher proportion of female voiceovers (though this gender difference in voiceovers was not statistically significant), which runs in opposition to the existing literature. Voiceovers are commonly associated with authority (Bretl & Cantor, 1988), so this finding is a particularly surprising one. This finding might be connected with the fact that voiceovers were associated with the gender of the primary character and female primary characters dominated Korean TV ads. As previously stated, one reason for that might be the dominance of the female audience during prime time, making it the potential target group of these advertisements.

Overall, there have been some changes in South Korean television advertisements that run against traditional Confucian values, such as the traditional gendered division of labor and home, a traditional role division that was not seen in television advertisements. However, from the perspective of social cognitive theory, we should not neglect the possible influences of continuing and problematic gender representations (Oppliger, 2007), especially for the representation of age and body image. Females, in particular, are still predominantly shown as young, and almost no older women are featured. This is a finding that cannot be explained by the viewers of prime time at all, since the majority of women watching TV during prime time are actually older women (KOBACO, 2006). This shows the limitations of practical considerations and the importance of cultural and social considerations in analyzing this phenomenon. This age imbalance between males and females confirms the “double standard of aging,” in which society is much more accepting of aging in males than in females (Sontag, 1997). Such representations also have social consequences. Research has revealed that the media can influence how older people perceive themselves (Donlon, Ashman, & Levy, 2005; Mares & Cantor, 1992) and how they are perceived by younger people (Gerbner et al., 1980).

What is true for representations of age is also true for representations of body types. Previous research has shown that women’s self-image becomes significantly more negative after viewing media images of thin women and that media consumption preferences predicted women’s eating disorders (Groesz, Levine, & Murnen, 2002; Levine & Harrison, 2009; Levine & Murnen, 2009). In a comparative study, Jung and Forbes (2006) found higher rates of body dissatisfaction among Korean university students than among students in the United States. These findings are surprising in a culture where thin bodies have traditionally been associated with ill health and reduced fecundity and where modestly plump bodies were admired. However, in South Korea, society has clearly changed, and a Westernization of beauty ideals has become evident (Jung & Forbes, 2006; T. Kim, 2003). It should not be forgotten that among the celebrity group, almost all female celebrities were young and thin. This finding does not, however, imply that a lack of identification between viewer and celebrity might lead to a weaker desire of the viewer to model her behavior on the character’s behavior. Based on the fact that South Korean women, in particular, follow celebrity-led trends (cf. Jung & Lee, 2009), this pattern might even lead to stronger modeling behavior than in the case of non-celebrities.

This study has provided an analysis of gender representations in South Korean television advertisements. What was found was a mix between stereotypical and traditional depictions, such as the dominance of young females with thin bodies in certain product categories associated with gender, and such counter-stereotypical depictions as the dominance of female characters, and no gender association for the settings and voiceovers. Overall, these representations do not confirm the hypothesis that the Confucian society of South Korea should have a strong gender division. The study also does not reflect the results of the Project GLOBE and the Global Gender Gap Report, in which South Korea scored especially poorly (Hausmann et al., 2010; House et al., 2004). Previous research in other countries has shown a high degree of gender differences and stereotypes (Furnham & Paltzer, 2010), while the results in this study were mixed.

These findings might reflect the actual situation in South Korea, where the role of gender is in flux in a culture that is in a constant negotiation between traditional and Western culture. Also, economic development clearly plays a role in the changes occurring in contemporary gender situations in South Korea. There definitely have been improvements in the labor situation for women. This might be reflected in the settings, voiceovers, and the dominance of female primary characters in television advertisements and, overall, in females being the main target audience. The predominance of young and thin females might be a form of Westernization in a country that valued traditionally less skinny women and highly respects age. However, one has to be careful to consider changes only into the context of Westernization. There can be many reasons for changes, and it is not always clear if they are based on a changing culture. Even if this is the case, can we really speak about Westernization if other players, such as other Asian countries, are involved in the process as well?

This research has provided some new insights into gender representation in South Korean television advertisements. Nevertheless, we can only speculate about the possible effects on audiences. As a result, we recommend that more research studying the effects of gender representations be performed. In addition, we have investigated only primary characters and adults, a limitation that restrains the amount of information on gender representation gleaned from the television advertisements to a certain extent. Future research should consider including more characters, and also children. Lastly, our research was based only on prime time commercials, limiting the inferences that can be made regarding the gender representations of a whole day of television advertisements. As a result, we suggest that future gender research examines the differences in representations between different television time slots in South Korea.