The traditional theme of the prostitute in popular texts has been ubiquitously employed in different times and cultures. In the South Korean context, the cultural representation of prostitutes was most prominent in ‘hostess (a Korean euphemism for prostitute) films’ during the 1970s. This was an ironic turn of events, given that state censorship was at its peak during the military regime (1960–1979). During the 1970s, South Korean cinema was often referred to as having hit a low point due to state regulation of films. However, hostess films became box office hits and contributed to the rejuvenation of the declining Korean movie industry.

Hostess films are characterized by the dichotomy of realism and the hyper-stylistic representation of their heroines. They dealt with realistic issues related to the migration of peasant women during the industrialization of South Korea and involve the contra-dictory presentations of highly unrealistic, idealized heroines. While conventional Holly-wood films portray sexually fallen women as immoral and eroticized, hostess films instead, focus on their extremely selfless and inherently good natures. The sacrificial qualities of hostess women often involve films with tragic endings that generically conclude with a heroine sacrificing herself for the sake of a man, a family and/or a nation. This article traces the cultural construction of the prostitute in popular texts and scrutinizes the major conventions of South Korean hostess films. In doing so, this work unspools how wider discourses concerning female sexuality, gender, and cultural politics were waged over the films’ deployment of the bodies of women and sex during a key formative period of Korean history.

The brief synopsis above may appear to be a story of a particular film but is actually a common archetypical narrative for many South Korean hostess (

Korean newspapers during that time period severely criticized hostess films, pointing out that such films were just an expedient commercial resort that sought to overcome the recent decline of the film market. For example, a newspaper article, “Desperate Korean Films” addresses the problem that hostess films are a reflection of the fact that Korean cinema was losing its quality. It states that “hostess films only focus on stripping off actresses’ clothing to gain audiences.”2 Film critics also mentioned that the presence of such obscene materials might lure young Korean girls into prostitution.

These negative views of hostess films have changed little since the 1970s: contemporary Korean film scholars continue to criticize hostess films for their sexual explicitness and lack of socially realistic representation. For instance, hostess films display “exploitive objectification of hostess bodies while dramatizing the decadence of their sexual adventures” (Pak, 123); “they did not exhibit any real analysis or criticisms of society, nor did they expose the irony of a society that put the heroines in such situations” (Min et al., 55); “hostess melodramas utilize explicit sexism by using women’s sexual and physical repression as a dominant strategy” (Yu, 143); “hostess melodramas exploit young working-class women’s bodies and sexuality by depicting them as ‘docile bodies’” (Kwŏn, 417).

Other film scholars nevertheless attempt to view the thematic employment of prostitutes in hostess films in relation to the rise of female labor in urban areas and subsequent problems during the rapid industrialization period of the 1970s.4 And these films dealt with actual social problems, such as sexual harassment and rape in the workplace, which frequently led to women winding up in brothels.5 Kim So-young (Kim So-yŏng), a Korean film scholar, sees the rise of hostess films as a symptom of state-initiated industrialization which “involved ex-ploitation of cheap female labor by controlling their sexuality” (185). Indeed, the late 1960s and the 1970s witnessed large-scale migrations of young women and men from peasant households to factories in cities. The number of female laborers who were over the age of sixteen during this period skyrocketed to 45.7% in 1976 from 26.8% in 1960. Kim asserts that the primary reason for the increase in the number of female laborers was because in Korean rural households, a filial daughter’s sacrifice for the sake of her male siblings or her parents was a “familiar and sacralized Confucian custom” (26). Thus a young woman’s sexualized service labor was mobilized “initially at the level of family and the domestic sphere through intersecting ideologies of familism and patriarchy” (ibid.).

In a similar social context, Lee Jin-kyung connects the issue of labor and sexual exploitation of female rural migrants to the emergence of the literary “hostess genre” on which the majority of hostess films were based.6 Lee describes that the prevalence of the sexual harassment and sexual offenses against young female laborers often made sensual stories for a mass culture industry in the form of films, TV and tabloid magazines.7 She points out that hostess novels such as

These scholarly viewings are useful insofar as they at least assess hostess films as socially relevant texts that deal with the real problems and hardships of the working class and prostitutes. They however do not raise the issue of how specifically these ‘dangerous’ subjects could be rendered on screen given the notorious state censorship in operation during this time, as the state was particularly wary of the representation of lower class life and poverty.8 As Park illustrates in her study of state censorship practices during the 1970s, the Park regime removed all scenes and characters or prohibited the exhibition of a film if a film was too indicative of poverty or anything against the national-development campaign during the Park regime (Park, 66–68).

In hostess films nevertheless, such ‘dangerously’ realistic portraits of lower class life and poverty survived censorship without severe amendments or revisions when compared with other genre films.9 Many hostess films take place in urban areas and feature real life brothels and back alleys where prostitution was carried on. If the same measure of censorship had been applied to hostess films, portrayals of streets full of whore houses in

I suspect that this realism could be secured mostly for two reasons. First, the films’ protagonists are eroticized females who tend to be idealized and fantasized. Hostess heroines are constructed in remarkably fantasized and emblematic ways to either exaggerate or negate a woman’s existence through extreme close-ups, fragmented body shots and super impositions which work to dissipate the level of realism the films featured.

The second element that safeguards the filmic realism is the thematic employment of the woman’s sacrifice. Hostess films predominantly thematize a woman’s sacrificing for the sake of her man, family and/or society. In early hostess films such as

Therefore in-depth, textual analysis of hostess films is inevitable. This article scrutinizes the formal elements of hostess films particularly focusing on the films’ strategic juxtaposition of realism and idealization of the heroine. It simul-taneously relates such cinematic constructions of hostess’ bodies and narratives to the discourse on female sacrifice which work to dilute the socially acerbic subjects of films controlled by state censorship. Doing this will extend previous scholarly views of hostess films beyond simply seeing them as mere sexualized texts that seek to draw the decreasing number of film goers back to the theaters. In order to better understand the distinctive mode of representation of prostitute women in hostess films, this article offers comparative analyses to other cultural texts that centralize prostitutes and female sexuality in terms of characterization, narrative construction and stylization. Finally, two canonical hostess films, Lee Jang-ho’s

1These hostess films were ranked within the top five at the box office in that year. The Korean Film Year Book (Seoul: KOFIC). 2Kyŏnghyang ilbo, December 8, 1978. 3Kyŏnghyang ilbo, August 3, 1983. 4Korea went through dynamic economic reforms and rapid industrialization during the 1960s and 1970s under the military regime led by President Park Chung-Hee. According to Kim’s report on Korea’s economic progress from 1961 to 1981, the GNP tripled from $471 to $1,549. The primary fields of exports—agriculture, fishery, and mining shifted to labor intensive, light manufacturing fields including textiles and garments industry. Kim Kwan S. “Industrial Policy and Industrial-ization in Korea, 1961–1982” http://kellogg.nd.edu/publications/workingpapers/WPS/ 039.pdf. 5Barraclough states that working class women and girls were central to the industrialization of South Korea. During this period, “over one million women worked in the light manufacturing sector, an industry with factories all over the peninsula.” A significant number of these female factory girls were drawn to sex work, with “no available vents for their ambition, or possibilities for making money.” Ruth Barraclough, Factory Girl Literature Sexuality, Violence, and Representation in Industrializing Korea (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 72. 6Lee Jin-kyung describes these problems as being related to female factory labor. The media of that era frequently showed anecdotal evidence along the lines of “young women’s desperate pleas seeking advice in the newspaper columns.” The increasing exposure of the occurrences and offenses might have instigated the engenderment of hostess literature. Service Economies: Militarism, Sex Work and Migrant Labor in South Korea, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 87. 7Ibid., 85. 8See Park Yu-hee’s “The Study of Film Censorship System During Park Chung Hee Regime” in Yŏksa pip’yŏngsa, yŏksa pip’yŏng 99 (2012). 9For instance, the scenes that contain the explicit depiction of police and lower class residents in Young-Ja’s Heydays, brothels in Women’s Street and implied student demonstrations occurring on a university campus in Winter Woman remain intact whereas these kinds of cases were heavily regulated in Park’s examples of films.

THEME OF THE PROSTITUTE AND FALLEN WOMAN IN POPULAR TEXTS: NARRATIVE AND CHARACTERIZATION

The popular rendition of prostitutes or sexually fallen women is not unique to South Korean hostess films. It is prevalent in various time periods and cultures. It is found in places as varied as Victorian literature, early Hollywood films (e.g. fallen women films) and other national cinemas (Weimar street films), all of which employ prostitutes as a form of social satire or cultural text that subsumes the basic human values of desire, vanity and survival. Overall, popular representations of prostitutes have been ambivalent (Roos, 2006; Pullen, 2005; Pattnaik, 2009). As Patrice Petro notes, the idea of a prostitute developed into “an emblem for the cinema as a whole, typifying literary intellectuals’ simultaneous contempt for and fascination with an openly commercial (and hence “venal”) form” (8).

Petro mentions that the ambivalent social identities of prostitutes invited both hostility and defensiveness and that the prostitute became a primary icon that harbored multi-faceted meanings of life and society in various arts and cultural texts. In Weimar culture, Expressionist artists used the icon of the prostitute in various forms that reflect “facets of modern life as expressionists experienced… as the artistic personification that transgresses the social, moral and legal boundaries” (114). The socially transgressive nature of the prostitute is both celebrated and despised by the expressionists. On the one hand, the prostitute is a holy public figure. She is selfless and indiscriminating to humans and can liberate people from sexual and moral constraints. On the other hand, she is a quint-essential symbol of money and power in modern capitalist society. She commoditizes herself all night just as “the shelves in supermarket are constantly refilled.”10

Nevertheless, even as a symbol of capitalism, the prostitute is occasionally charged with positive values such as social activism and determination. These values allowed writers, including Bertolt Brecht, to deploy prostitutes to voice social criticism. Brecht’s prostitute characters such as Frau Hogge in

Positive portraits of prostitutes also appear in early Korean literature such as the New Novels (

Perhaps these literary and artistic works on prostitutes were relatively more progressive and ‘generous’ compared to the representation of prostitutes in the cinematic context, because presumably literary and artistic products were less constrained by censorship than was the case for films over which censors had more direct and immediate control. In films, prostitutes tend to appear pre-dominantly in a negative light, typically being accused of overt sexuality, immorality and greed. Largely infused with the Victorian epitome of ‘fallen woman,’ prostitute narratives are prevalent in early cinematic texts such as fallen woman films (1920s), White slavery films (1930s) and Weimar street films (

Some scholars see the roots of such negatively charged characterizations of prostitutes or sexually fallen women in early American cinema in Victorian models of characterizations of prostitutes (Campbell,1999; Fishbein,1986). In Victorian literature, the definition of a prostitute is often character-based and not simply sexually-based(Attwood, 2011). Ralph Wardlaw, an early Victorian writer, claimed that the term, prostitute was a “designation of character.” Prostitutes were characterized as women with weak will power and fatal moral flaws who “chose to select ‘the strength of the sexual propensity, and the comparative weakness of the moral principle’” (Attwood, 3). Accordingly, these Victorian prostitutes are often portrayed with common expressions such as ‘inherently immoral,’ ‘shameless,’ and ‘impulsive’ in their actions, because their choices were based on their innate nature of weakness.11

This idea of the Victorian prostitute transferred to the silver screen in early fallen woman films the 1930s. The quality of the heroine in fallen woman films is typically defined as sexually aggressive, materially driven, exploitative (especially in their relationships with men) and unashamed (Jacobs, 1997; Vieira, 1999). Jacob’s analysis implies that such negative qualities are not causally related to a woman’s sexual activeness. In other words, she is bad not because she is sexually active, but she is ‘innately’ bad and sexual activeness is simply one of the innately negative qualities that come with being bad. Such characterizations inevitably locate the sexual woman in an immoral position. Jean Hollow in

The characterization of the sexually fallen woman in early American cinema developed further and conventionalized into the more popular icon of the ‘femme fatale’ in noir films and later genres of action films or thrillers: numerous examples include Rita Heyworth in

These inherently negative qualities attached to a prostitute/fallen woman in popular media usually call for the woman dooming herself at the end. As some scholars point out, the industry’s self censorship canonized the narrative in which the fallen women is eventually destroyed in the service of the “moral standard of audiences” (Jacobs, p. 76; Fishbein, 1987; Staiger, 1995). Simply speaking, the fallen woman film could not have a happy ending, and if it did have a happy ending, it was “designed to fulfill a didactic function” (Jacobs, 76). The patriarchal discourse of the sexual woman ‘getting what she deserves’ became an axiom of early classical narrative films, whereby the narrative punishment of “downward progress” involves the fallen woman commonly ending up tragically with disease, destitution and early death (mostly suicide) (Attwood, 2010; Auerbach, 1982).

Indeed, the narrative device of the ‘downward progress’ of a fallen woman or a prostitute character works efficiently, fleshing out ideological norms of female sexuality. Also, applied to their social status, it solidifies representational stereotypes of lower class women. As Liggins exemplifies in her discussion of early Victorian prostitute literature, the working class status of the prostitute woman is often used to indicate her sexual openness.13 Liggins argues that working class women tend to be attacked on the grounds of “their sexual knowledge and consequent impurity … given that they have a ‘familiarity’ with and ‘completer knowledge’ of sexual matters than middle-class girls, therefore often considered very close to the shameless prostitute, even if they do not sell their bodies on the street” (41–42). Such stereotypes imposed on working class prostitute women function to justify the ‘prostitute narrative’ of a downward path, rationalizing the tragic ending of the prostitute.

As these examples demonstrate, the prostitute’s downward path is predominantly caused by her innate immorality and class background which is likely to be related to her sexual inclinations. The South Korean hostess films conform to this popular tendency of a downward narrative of a ‘fallen woman getting what she deserves,’ by giving the heroine either a pessimistic fate—by committing suicide (

However, as mentioned above, these virtuous traits of hostess women do not necessarily lead to happy endings, and the unhappy endings in turn dramatize and emphasize the sacrificial theme of the hostess woman’s life even more. Unlike the typical triumphant happy endings that involve innocent, wholesome female characters in classic Hollywood films such as

The episode concerning the ending sequence of

This ambiguous ‘happy’ ending can also be found in another hostess film,

In terms of technical aspects, the sacrificial and selfless heroines in hostess films are visualized in an abusive and exploitative manner. Some Korean film scholars have pointed out that the exploitative use of close-ups and fragmented body shots involving female protagonists is one of the dominant features of hostess films (Yu, 2000; Kim, S., 2012). Drawing on Laura Mulvey’s notion of woman as a visual spectacle in narrative cinema, Kim Sun-ah points out that Young-ja’s face in

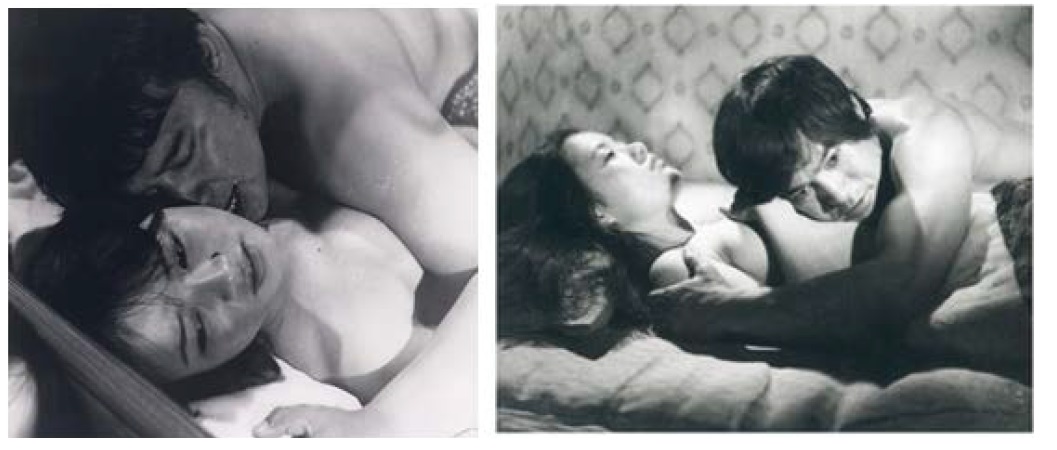

Nevertheless, I would argue that the representation of women found in hostess films is often shown in a way that de-eroticizes or actually obscures women’s presence. More particularly, the facial close-ups of hostess women in sex scenes tend to be predominantly de-eroticized. Instead of exaggerating women’s sexual engagement, hostess films rather focus on their ‘unnaturally’ emotionless facial expressions and static bodily movements. The woman is displayed as being somewhat ‘machine-like’ and lacking in human emotions even when she is with the man with whom she is romantically involved. One of the hostess woman’s defining characteristics is her ‘selflessness,’ which is visually rendered throughout these sexual scenes. As two stills from the hostess films,

In addition, these female expressions are occasionally shot from the camera eye from the male point of view, using a high angle from which the male looks down on the heroine (Figure 3-2). Throughout

Accordingly, the hostess woman tends to be ‘captured’ within the male perspective, which in turn hinders access to the woman’s presence. The camera technique is often accompanied and empowered by the thematic convention of a male voice over, flash backs and dream and fantasy sequences led by male characters. Two canonical hostess films, Lee’s

10The poem by Oscar Kanehl. “Nachtcafe” (1913). Quoted from Christiane Shonfeld’s “Prostitutes in Expressionism,” Commodities of Desire (Rochester: Camden House, 2000), 119. 11Emma Liggins. “Prostitution and Social Purity in the 1880s and 1890s.” Critical Survey. Vol. 15 No. 3. (2003). 12John Blaser, “No Place for a Woman: The Family in Film Noir,” 2008, http://www.lib. berkeley.edu/MRC/noir/np05ff.html. 13Ibid. 14During his interview with the author, Kim stated that this version was designed in order for the film to pass the censorship which would not have passed such a tragic and pessimistic ending because it could be seen as being more “socially critical.”

To explain the enormous financial success of

Soon afterwards, Young-ja is kicked out of the house by the son’s mother who blames and denounces her as an “ungrateful bitch.” From this point onwards, Young-ja’s life gradually goes downhill; after wondering about a series of meagerly paying jobs, she finally works as a bus conductor. She is happy in this job but loses her arm in an auto accident. She has nowhere else to go, so she goes to a brothel where she works under the name of Venus, the nickname she acquires because she only has one arm. The film returns to its beginning, where Young-ja reunites with Chang-su at the police station. Chang-su hopes to start a new life with her but their romance does not last very long. Young-ja thinks that she has been tainted by her experiences and will never be good enough for Chang-su. She decides to leave him and marry a man who is disabled just as she is.

As the narrative demonstrates, Young-ja, despite her inherently good, sefless nature, undergoes events throughout the film—leaving home → amputation of her arm → prostitution → sacrificial marriage—that are progressively worse and impose bigger costs on Young-ja. Symbolically, these incidents that Young-ja experiences throughout this film, such as rape, injury at work and moving into the sex industry, etc. are all similar to the type of issues frequently experienced by working class women particularly during the rapid industrialization period.18

This thematization of working class hardships could be read in conjunction with the state concept that Park Chung-hee designed and campaigned for in order to expedite the industrialization process. The Park administration emphasized the spirit of “giving back” to the nation for the prosperity of the state. Participating in the national project of modernization was not optional but rather “the Korean people’s duty” (Park, 80). With the enactment of this campaign, the Korean people, particularly women were subjected as a public offering for the “greater good.” This vigorous national project that imposed sacrifices people was doubly worse for women. Lee Jin-kyung explains that states played a significant role in “mobilizing and legislating working-class women’s sexuality, that is, in industrializing sex.”

The Park government established a series of laws, regulations and legal mechanisms during the 1960s and 1970s that were intended to indirectly facilitate the enlistment of working class women in the profitable sex tourism industry (22). During this time, women were not only utilized as cheap labor in sweatshops but also manipulated to meet the need for the sex workers. Park simultaneously promoted tourism as a source of foreign exchange “to replace that previously acquired through participation of Korean troops in Vietnam…the number of Japanese tourists to South Korea jumped from 96,531 in 1972 to 217,287 in 1973 in just one year promoting sex tours…”19 The Park administration issued work permits that legitimatized prostitution at hotels that catered to foreign travelers in 1973 in order to boost the tourism industry.20

The opening sequence begins with the camera back-tracking a little boy who is slowly walking around back alleys. It is a dark night. The only thing that the audience can see is the dimly lit sign of a humble motel located in a presumably recognizable area in Seoul where small lodges and motels are crammed together in order to lure male clients. The subjective camera is hand held and aimlessly wanders every corner of the street showing drunken men passing by. Finally the camera stops to focus on some unknown woman’s face using an extreme frontal close up. She is waving her hand in strong denial. The viewers soon find out that she is a prostitute and the camera ‘eye’ was a police man. She is arrested and the man who was hiding behind her is seen running away. In the following scene, the heroine Young-ja appears in a similar extreme close up shot and is also arrested indicating that she is one of these prostitutes too.

The sequence conjures a documentary-like effect by offering a vulgar and yet sincere portrait of tenement life by displaying poor streets. The film invasively tracks the back of an anonymous by-passer on a small dark street. The extreme low key lighting obscures the faces of bystanders but only spotlights the dilap-idation of the street: torn-off posters, blinking street lights and run down houses. However, these markers of lower-class poverty and desperation are conspicuously shown by the streetwalkers’ shabby outfits and slouched postures. In addition, their status is metaphorized through degrees of visibility. The main characters do not appear until after the camera completes such a lengthy, meaning-laden sketch of the dark street in a city that is teeming with people and objects all of which are indicative of lower class reality.

This quasi-documentary introduction breaks its mood with representations of female characters, particularly through the use of close-up shots of the prostitute heroine accompanied by sound muting. Such a lack of sound is accompanied with the heroine’s exceedingly visible, frontal close up that emphasizes her facial expressions either in pain, fear or arbitrarily emotionlessness. In the opening sequence, for instance, the first prostitute who is caught by the police and Young-ja are shown in their huge wigs while holding their artificially red lips wide open, supposedly screaming and denying that they are prostitutes. Because these visual indications are off-sound, the viewers are prompted to focus more on the visual elements.

What is striking in this sequence is the prominent contrast between the mode of representation which realistically renders the street by using hand-held cameras and location shooting. It simultaneously presents elaborate visuals of women using close-ups paired with muted sound which invokes her presence as an ‘image’ rather than an actual presence. This contrast establishes the woman as being ‘incorporeal’ in that she is simultaneously existent and non-existent. It resonates with feminist accounts of filmic representation of women: how women and women’s bodies are both visible and invisible in popular cinema. She must be ‘corporeally’ visible for male pleasure but at the same time she is invisible because her existence is imagined to reach such goal.

In numerous instances, a woman’s body becomes a crucial means of accomplishing these ends. Williams has noted that because a woman’s body invokes powerful sensations with her sexuality, women on screen have been inserted into various levels of cultural discourses and are subjected to various cultural functions that a given society needs to reinforce. This mode of address visualizes woman’s labor (body) as amorphous and transitory and directly relates to the question of women’s agency. Janet Staiger notes that woman’s agency, or as she puts it, “the essence of woman” in movies is often seen as the “transitory object (here woman)” which works as “an ideological maneuver attempting to stabilize an eternal subject (here man)” (12).21

The opening sequence of

The elaborated visualization of the woman presented above is reiterated and simultaneously contrasted with the realist sets of the

This somewhat abrupt ending maximizes the bridge between realism and the stylization of the heroine in the opening sequence. Unlike the candid sketches of the

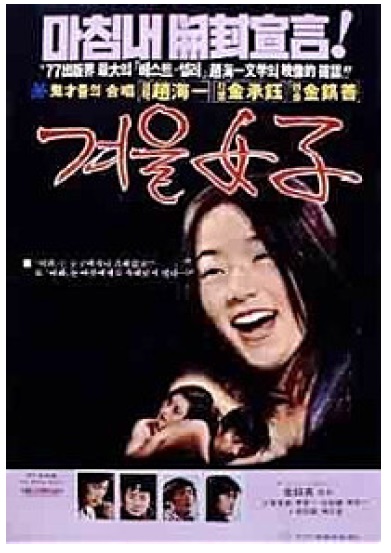

A meaning-laden copy line of another hostess film,

Throughout the film, Young-ja is continuously excluded and subordinated to male characters through various techniques of fragmentation (facial and bodily close-ups), super-imposition and sound mutation. These techniques function to accentuate and idealize the female sacrifice for the sake of her family and men—Chang-su and her disabled husband.

Similar visual techniques and thematic elements are employed in an equally successful hostess film,

The film was a record breaking hit in 1974. It attracted an audience of 464,308 which led to the production of two sequels (1979, 1981). The film also won numerous awards, including the Best New Director Award at the Grand Bell Awards (1974) and the Baeksang Art Awards for Best Cinematography (1975), which demonstrated that the film was critically valued as well. Some critics attributed the success of the film to its candid depiction of the changes in women’s life in an industrializing society: “Indeed, at the time, numerous women who came to the city during the course of Korea’s industrialization and modernization worked as hostesses in bars, and the movie reflects this state of affairs,”22 Cho mentions that hostess films such as

These accounts convincingly suggest that

The film begins with Mun-ho holding a white box which appears to be a funeral urn. The narration states that it belongs to Kyŏng-a. The film flashes back to where Mun-ho first encountered Kyŏng-a. The camera shows Mun-ho in a bar drawing someone in his sketch book. Then Mun-ho looks at the subject of his sketches, Kyŏng-a, who appears in heavy make-up and wearing a flamboyant wig, which signal her current profession. The camera in a tableau exhibits her actions—sipping her drinks and smoking, slowly paced. The camera then returns to Mun-ho’s drawing and his gaze towards Kyŏng-a. She is shown again in another tableau with more dramatization: her repetitive drinking and smoking are again slowly paced using intense lighting, making her look somewhat ‘staged.’ The scene is exclusively framed for her. The presence of the bartender is indicated off-screen, only showing the hands of the bartender pouring drinks and lighting her cigarettes.

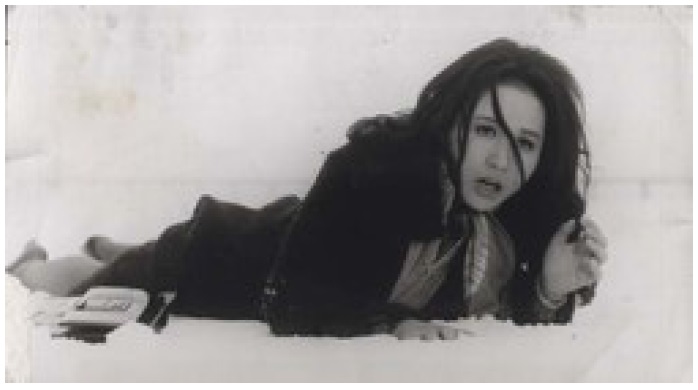

The ‘staging’ of Kyŏng-a is maximized in the final sequence. The scene starts with a landscape view of a vast plain that is completely covered in snow. Kyŏng-a appears out of nowhere and slowly walks in a zigzag manner towards the camera positioned in front of her. She stumbles and takes out the sleeping pills wrapped in her handkerchief. In an extreme close-up, she hallucinates and smiles at her very first love, Yŏng-sŏk whom she imagines running towards her. She soon recognizes that it is a hallucination. She frowns and slowly consumes a larger quantity of sleeping pills followed by a handful of snow. Her persistent dialogue with herself, “I should not fall asleep here,” emerges as an internal sound which contradicts her consumption of sleeping pills.

In a manner similar to the opening sequence of

The two films,

In this article, I have demonstrated how South Korean hostess films endorsed and nurtured the cinematic construction of female sexuality, idealized in a way that complies with the patriarchal discourse of women’s sacrifice. Although I have dealt with a particular film genre from a particular period, the re-presentational mode of femininity in hostess films resonates with women in other popular Korean film texts. As mentioned previously, I am particularly concerned about the persistently recurring notion of female sacrifice which imposes woman’s labor and sex as a form of compensation (both thematically and visually). This generic tendency was not limited to the genre of ‘hostess films’ but was widely employed in subsequent films of the 1980s, such as the erotic historical films (

15During the 105 days after its premiere, Heavenly attracted around 465,000 filmgoers and also recorded the largest film audiences for 1974. 16Pak Mi-suk (Park Mi-Sook), “Yŏnghwa rŭl t’onghae pon maech’un pogosŏ – Yŏngja ŭi chŏnsŏng sidae esŏ” (Report on prostitution through the film, Young-Ja’s Heydays), Mal (Words), December 1972)., Kwŏn Ŭn-sŏn (Kwon Eun-sun), “Kŭ sijŏl, Yŏng-ja rŭl asinayo?” (Do you know Yŏng-ja from that period?) in CINE21, December 28, 1999. An Pyŏng-sŏp (An Byung-Sup), “Ŭmji ŭi insaeng ŭl t’onghae pon minjung ŭi sam kwa kŏn’gangsŏng—Yŏngja ŭi chŏnsŏng sidae”; (Looking at the life and health of the Minjung through a dark life, Young-ja’s Heydays) in Cine-Reality, Imaginative Reality, Chŏngŭmsa, 1989. 17Roh Ji-Seung. “The Pleasure of a Lower Class Woman in the Movie Young-Ja’s Heydays (Yŏng-ja ŭi 全盛時代 [chŏnsŏng sidae]”—An Essay on the Cultural History of Class and Gender” in The Study of Korean Literature (2008). 18Cho Oe-Suk, “Han’guk yŏnghwa e nat’anan hach’ŭng kyegŭp yŏsongsang yŏn’gu—1970 nyŏn-dae yŏnghwa rŭl chungsim ŭro” (Analysis of lower class women and female laborers in 1970s Korean films) (2002). 19Yoon, “Agenda Building in South Korea,” in Handbook of Global Social Policy. Ed. Stuart Nagel (Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2000), 172. 20Cho Oe-suk, “An Analysis of Lower Class Women,” 32. 21Staiger particularly talks about movies in their teens, how the construction of women’s representation was practiced even in the primitive cinema. Bad Women: Regulating Sexuality in Early American Cinema (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995). 22Quoted from the notes on the film, The Korean Film Archive. http://www.koreafilm.org/ feature/100_52.asp. 23See Cho’s “The Analysis of Lower Class Women and Female Labor in the 1970s and 80s Korean films,” MA Thesis (2002).