The Bible is never read in a vacuum, insofar as it affects believers in their own contexts as a “Word of God” to live by. Whether the interpreter is aware of it or not, the context serves not only as a choice, but also as a consequence. It is a choice because the interpreters choose to read from a particular location. It is also a consequence because biblical interpretation has powerful effects on people and their lives in certain ways. Hence, critical readers have to make explicit at the outset their own context and bring to critical understanding their own interests and perspectives.

My reading of the Bible in general and the Gospel of Luke in particular emerges from an East Asian global context, where globalization becomes a new world order and its own rule and conception creates scarcity. This context informs my reading of the text. However, the same context is also informed by my reading which helps me to see it in a new light. In light of the Gospel of Luke, I see that the People of God struggle with a lack of agency under the construct of power.

The issue of human agency is such an “uncomfortable” subject in my native South Korea, which was one of the poorest countries in Asia until the 1960s and has grown into the tenth largest economy of the world. In a country, still gripped by the memory of the colonial rule and the ethnic, national divide, the “World” within and beyond has been heavily influenced by what Althusser calls “ideological representation of ideology.” 1)

During the latter part of the twentieth century, South Korea was governed by a military dictatorship that had served the Japanese Empire and then quickly turned to the U.S. for its protection.2) Consequently, the Japanese colonial legacy and the American hegemony have long supported each other in South Korea. At the same time, the domestic power has combined itself with such discourses as anticommunism, modernization, and globalization, which have followed one after the other, each supporting the next.

Being haunted by the memory of colonial cruelty and exploitation, South Korea has cultivated its own colony - not a “colony” abroad, but a “colony” within.3) Thus, while problems and contradictions emerge from the life of the colonial and postcolonial subjects, South Koreans must relegate them to a distant past and move on rather than contest and resist in their present (hi)story. They were deprived of their own (hi)story, culture, and language, while being harnessed for modernity, progress, and development - in Partha Chatterjee’s words, to experience “continued subjection under a world order which only sets their tasks for them and over which they have no control.” 4)

Therefore, what the colonial and postcolonial subjects desperately wanted and still cannot acquire is their sufficient agency and freedom. Their lack of agency, however, arises most poignantly today in globalization - a process of appropriation that reaches across diverse cultural, ethnic, and racial identities while creating ‘inside’ / ‘outside’ boundaries. With regard to the current globalization, Fernando Segovia traces it to the last five hundred years of imperialism and the domination of capitalism:

At each turn, human identities are contested, challenged, and often jeopardized by strife and scarcity. Throughout this history, the poor - the “others” of history - always have been present, crying for a more just world.

However, the issue of living together, as well as the representation of self and other, has drawn limited attention from modern (mostly, western) economics, while the over-representation of scarcity has been widespread.6) Biblical studies also have increased knowledge of wealth and poverty. However, biblical criticism’s seemingly “impartial” and “neutral” measures have not advanced the awareness of how the construction of political economy pertains to such a topic, while the value of such practices as “almsgiving” is dragged into the politically charged zone of economy.

This paper seeks a connection between human identities and agency, especially with regard to those materially poor who are locked out of the prevailing political-economic paradigms. For my overall project, I ground myself as a real reader, immersed in a specific historical, cultural, social, and geographical location. From such a location, I take into account the (hi)stories of Korean minjung as another text and evaluate as well as analyze in dialogue how a biblical text stands with regard to the particular East-Asian global context.

To begin with, I illuminate the social memory of

1)Louis Althusser, Essays on Ideology (London: Verso, 1984), 36-42. According to Althusser, “ideology is a representation of the imaginary relationship of individuals to their real conditions of existence,” and “their imaginary transposition is caused by a few men who base their domination and exploitation of the people on a falsified representation of the world which they imagined in order to enslave other minds by dominating their imagination.” As he points out, the “ideological representation of ideology” has influenced people to have a “consciousness” or “belief” in particular ideas, according to which they must act and conduct themselves, lest they become deviant. 2)For further elaboration, see George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2008). 3)As Franz Fanon observes, in this situation, the combination of colonialism and such other discourses forms oppression that runs tighter. The Wretched of the Earth (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1991), 148-205. 4)Partha Chatterjee, Nationalist Thought and the Colonial World: A Derivative Discourse? (London: Zen Books, 1986), 10. 5)Fernando F. Segovia, Decolonizing Biblical Studies: A View from the Margins (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2000), 127. 6)I find myself in agreement with the alert offered over the assumptions of modern economics and their solid presupposition of scarcity by Douglas Meeks, God the Economist: The Doctrine of God and Political Economy (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1989), see esp. 15-28.

Does Minjung-Jesus Still Live?

In a context such as mine, the presence of the Korean

Since the seeds of capitalism and its infrastructure were first laid in Korea during the Japanese colonial period (1910-1945), colonial and neocolonial development has continued upwards. Economic success made possible by the

At that time, one famous poetic expression of discontent came in the form of a parody, “Five Bandits,” by Kim Chiha. “Five Bandits” employed stylistic features of

Upon being released, Kim Chiha wrote another

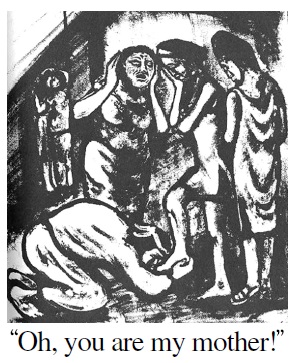

By way of this awakening, Chang not only recognizes but also invalidates the code of “identity thinking” - for Adorno, a “covertly paranoid style of rationality” which inexorably transmutes the Others into a mere simulacrum of humans or expels them beyond the human borders in “a panic-stricken act of exclusion.” 9) After his awakening, he himself becomes an itinerant preacher, proclaiming the liberation of people. He calls prostitutes his mother, kisses their feet, and declares:

Chang meets and argues with various urban mission pastors, priests, intellectuals, professors, trade union leaders, monks, servicemen, and social workers.

He acknowledges his own life as a journey going in a reverse direction to that which most people have been forced to take. He leads his disciples up a mountain and teaches them the philosophy of

Chang proclaims in their midst:

When the big march comes closer to the capital, the authorities get more confused and more frightened. The journey of Chang and his disciples goes against the flow of the multitudes undertaking their daily journey, an “endless transmigratory pilgrimage to their destination and then a return to the place where there is no food.” 14) These multitudes throng around Chang and his disciples, adding to their numbers. Before Chang finishes his journey, however, he gets arrested. He was betrayed by one of his disciples, another down-and-out.

The authority takes him out in order to execute him in public for conspiring against the throne. At the moment, he begins to sing a song, entitled “Food is Heaven” :

Finally, Chang is beheaded. Three days after his decapitation, however, he returns to life. His resurrection is so strange that his head is put on the betrayer’s body, and the betrayer’s head on Chang’s body. The head speaking justice and truth is bonded to the body carrying injustice and falsehood.

Presumably, such a strange scene promises resurrection not to physical bodies, but to hybrid existence woven out of “self” and “other,” regardless of whether or not each is recognized as “good” or “bad.” For Kim, this is the resurrection - an embrace that is truly celebrative, from which the notion of political economy shall flow. In the face of conceptual straitjacketing, Kim affirms heterogeneity over and against the tyranny of seamless homogeneity. Chang already witnessed the Otherness - a “God” - in a grimy cesspool of humanity.

As such, Kim envisions Chang’s birth, itinerating, preaching of liberation, trial, and execution as the reproduction of the life of Jesus.16) Those prostitutes, prisoners, and beggars, with whom Chang joins himself were, in fact, the

However, when Chang finds the truth at the bottom, the bottom turns upside down and becomes heaven. Chang’s resurrection is an initiation into mysteries, enabling those marginalized to perceive and understand what is otherwise beyond human perception and understanding. Through the carrier, a body of the “evil,” the news of liberation becomes widespread as by a wild and stormy wind.

7)The concept of minjung first came to the fore when people in a rural area flocked to urban centers after the Korean War (1950-1953). 8)Kim Chi Ha, The Gold Crowned Jesus And Other Writings, eds. Chong Sun Kim and Shelly Killen (Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 1978), 27. 9)Terry Eagleton. Ideology: An Introduction, 126; Theodor W. Adorno, Negative Dialectics, 1973. 10)Kim Chi Ha, The Gold Crowned Jesus And Other Writings, 27. 11)Ibid., 29. 12)See Suh Namdong’s discussion of Dan, “Towards a Theology of Han,” in The Commission on Theological Concerns of the Christian Conference of Asia, Minjung Theology: People as the Subjects of History (Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis, 1983), 55-72. According to Suh, Dan (meaning the act of “cutting” ) is the poet’s self-denial. One’s enlightenment (or revolution) should be accompanied by living as “a wayfarer, leaving everything behind.” Dan also conveys a social dimension of the people: “Cutting the vicious circle of revenge” for “the transformation of the secular world and secular attachments.” If needed, Dan ought to be developed into a decisive and organized explosion. This transition lies in “religious commitment” and in “internal and spiritual transformation.” I will address the theme of “commitment” and “internal/spiritual transformation” in the concluding chapter. See Suh (1983), 56-57. 13)Kim Chi Ha, The Gold Crowned Jesus And Other Writings, 28. 14)Suh Namdong sees the life of Chang as the social biography of the Korean Minjung. Suh notes that: “religious ascetism, revolutionary action, a yearning for the communal life of early Christianity and a deep affection for the valiant resistance of Koreans are all part of Chang’s kaleidoscopic world.” For Suh, some of those movements and ideas combine and coalesce, and others clash in confrontation. See “Historical References for a Theology of Minjung,” in eds. The Commission on Theological Concerns of the Christian Conference of Asia, Minjung Theology: People As the Subjects of History (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1983), 155-182; esp. 177. 15)Kim Chi Ha, The Gold Crowned Jesus And Other Writings, 30. 16)David Suh describes Chang’s life as “complete conformity with the han of hell.” According to Suh, Han which is a feeling of helpless suffering and oppression becomes the most important element in the politico-economic consciousness of the minjung. See the discussion of David Suh, “A Biographical Sketch of an Asian Theological Consultation,” in Minjung Theology: People as the Subjects of History (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1983), 24-28.

Challenge of Minjung Theology Today

The word

What particularly caused his suicidal protest were the miserable lives of “See-da,” who worked in a sweatshop covered with dust, from early morning to midnight every day. The term “

These “

For the

First, they bear “the remaining suffering” of Messiah. In Matt 25:31-46, for example, the poor, the weak, and those who are in need of clothes and have nowhere to go are identified with Jesus. They are “Jesus in disguise.” A man who suffered at the hands of robbers in Luke 10:30-35 also can be a type of Messiah, playing a Messianic role, a role of Jesus Christ. He was half dead and cried out for help. His groaning and crying is a symbol that repeatedly asserts itself in the process of history and controls what one may find in the cultural text.

By presenting the despised

Second, tainted as they are by colonial exploitations, the identity of

In this regard, Suh states that:

The affirmation of those participants as a

With hope both for and against historical realities,

For early Minjung Theology, the “social biography of the

For an East Asian global reader, recourse to the

17)The word minjung indicates common people who undergo socio-cultural alienation, economic exploitation, or political oppression. Kim Yong-bock states that “the reality and identity of Minjung is not to be known by the philosophical or scientific definition of the character or substance of minjung. It is to be known by the story of minjung, that is, the social biography created by minjung themselves.” Kim Yong-bock, Korean Minjung and Christian (Seoul: Hyungsungsa, 1988), 110. 18)Suh Namdong, A Study on Minjung Theology (Seoul: Hangilsa, 1980). 19)Ibid., 181; emphasis mine. 20)Ibid., 180-81. 21)This seems peculiar when compared with the Hebrews exodus from bondage in Egypt. Richard Horsley asserts that those Hebrews are the very prototype of people claiming its agency. See Richard Horsley, Covenant Economics: A Biblical Vision of Justice for All (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2009), 18. 22)Indeed, listening to those stories and voices from the margin should broaden one’s knowledge and information base, provoking the process that becomes a discursive conscientization. See Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (New York: Continuum, 1993), 52-53. 23)Kim Yongbock, Korean Minjung and Christian (Seoul: Hyungsungsa, 1988), 110. 24)Hyun Younghak, “A Theological Look at the Mask Dance in Korea” in Minjung Theology, ed. Commission on Theological Concerns of the Christian Conference of Asia (CTC-CCA) (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1983), 47-54. 25)Ibid. 26)Freire (1993): 52-53.

The Parable of the Prodigal Son

The Parable of the Prodigal Son unveils a material construct of economy that carries out the norms affirming “this is the way things are” or “should be.” In order to disclose what is really at stake in the parable, there is a need to reconstruct the submerged voices emerged within the

The older son disparages himself as a slave at home, when his father champions his voiceless younger brother as the cause for celebration. The kyriarchal order hinted at in his speech carries out the authorization of scarcity. The father as a property owner, a slave master, and a patron to clients, exerts both “material and moral power over those who live in and around” the household, as Paul Veyne states. With the

In this regard, the older son is a counter-model, an illustration, or clarification of the problem in Luke’s

When the deprivation of the older son emerges from the power problematic, its mode of relational polarity should condone silence or engender mimicry. For its victims, poverty becomes an intention or discipline of “God,” just like the younger son says to the father, “I have sinned against heaven” (Lk 15:18, 21). For its masters, on the other hand, it only reinforces opportunities to develop a vast source of patronage and to evade accountability. This makes it very difficult for colonial subjects to discern the call of God to act and resist (Lk 15:29).

Hence, turning the older son’s speech into a personal confrontation, the way most commentators do with this parable, could undercut any chance of envisioning human subjectivities, or what it means to be a human being, singularly and in community.28) For the older son, “the problem” is not the lack of loyalty, but the lack of agency to live the kind of life he has reason to value, ‘that [he] may celebrate with his friends.’ A young goat he refers to becomes goods that not only define his subjectivity, but also his communal experience.

The older son has long internalized the rule of kyriarchal boundary. He could not go out to celebrate with his friends, since, for him, the boundary is highly marked by the power of the

Thus, it is striking that the

What really strikes the reader herein, however, is not the father’s attitude, but the father’s construction of communion between the

The father’s sense of (comm)unity, in which self and other seem so interconnected and interdependent, allows one’s property to be absorbed in each other. The father’s utterance, “Son, you are always with me; all that is mine yours,” could amount to saying: You are neither indebted nor obligated to me, as you think, because you are part of the

This is not a zero-sum game, but a positive-sum game. The household as a whole widens and everyone in it wins. Its pervasive interdependence from within and without salutes the full humanity of shameful and honored, have-nots and haves, powerless and powerful, all embracing culture of a community caught in structural oppression. Hence, the sacred space of the family encourages human subjects to cross over imperial-colonial descriptions of the boundary between center and periphery, metropolis and the margins - in effect, the imperial and the colonial.

For the father, celebration serves as a symbolic act in which one can enter and participate as a community and communicate a different faith/vision and a sense of the move from the binomial polarities and contradictions to the heternomous communion and correlation. Those persons formerly conceived as voiceless and invisible, are reclaimed and become legitimated for the (comm)union of the

This new world that we hear from the parable is quite challenging, since it redefines what our culture sees as the problem with the economy, and therefore how we envision security for ourselves and our society. Luke’s housheold might be felt as unsettling and even as threatening. Indeed, few New Testament texts reflect to the same degree an awareness of the link between human existence and economy.

Within the reconfiguration of Luke’s household and its related, ideological stance against the empire, a postcolonial

27)For more detailed discussion, please see Rohun Park, “Revisiting the Parable of the Prodigal Son for Decolonization: Luke’s Reconfiguration of Oikos in 15:11-32,” Biblical Interpretation: A Journal of Contemporary Approaches, Volume 17,?Number 5, 2009: 507-520. 28)The manifest breach of rules in Luke is actually the condition for the alternative oikos and oikonomia to become more visible. When colonial agents apply dominant power to every corner of the household, creating scarcity, especially in a zero-sum colonial society, Luke’s oikos discourse tends to focus on entitlements rather than on loyalty, on rights rather than on discipline. Hence, the idea of ‘repentance’ alone, condoning the “like-indedness” under the Empire, fails to explain Luke’s substantial development of the human agents. The text of Luke does not give a chance to exploit the marginalized with a sense of indebtedness, inequality or immorality. 29)This cannot be told through narratives of success or failure, narratives with their endings in this present world. But it might take the form of eschatological genealogies, as in Luke (3:23-38) - a story that can be told only from a redeemed end that is continuously transcendent from the present moment. In this regard, Luke’s genealogy is a cultural turn to the culture of the now and the present Household of God.

While economy originally refers to a household, it also provides a norm, whereby self and other, or individual and community (communal selves), may live in a house in a manner that is both just and sustainable. Under the neocolonial dominance of global economy, however, the flow of economy has the effect of marginalizing the rest of the world, so that those on the periphery become merely a means of supplying the needs of others.

In this regard, Luke’s

Since globalization has become a new world order, its own rule and conception has been able to influence virtually every space in the world. Its deceptive appearance presents capitalist realities as natural and eternal - a continuing representation of ‘god,’ which is an idolatrous cult of Mammon.32)

Henceforth, when capitalism charges itself with domination and exclusion, poverty becomes the result of divine will, though it is an inevitable consequence of the nature of the capitalist market. It has thrived at the cost of such disenfranchised human subjects, while at the same time having excluded those who do not have the property which results from having a livelihood. This leads to a number of issues, or problems to be resolved: first, the market itself as the mechanism of global domination; second, commodification as the reality of the mechanism as such; and third, scarcity as the consequence of the domination and its justification.33)

First, while the market promises a free and harmonious way of integrating and coordinating society, its universal justification for “rational” choice is, in reality, a reflection of domination. Second, commodity chains emerge as the core of marketization. The whole process of commodification effectively reduces the lands and labor to rents (in place of lands) and wages (in place of persons) as well as limiting justice, health, and life. Everything in the commodity chain is commodified; the market renders all transactions inhuman. Third, as wealth is used merely as a means for gaining more wealth, scarcity emerges and it effectively denies others access to their livelihood.34) The Gospel tackles the problems and needs as such, while conveying a liberating new narrative for the people of God living under global capitalism.

In this regard, Luke’s representation of human beings suggests that my existence is not quite my own since my life is already bound up with the life of the Other(s). In addition, the relationship to self and other emerges in the

The teaching is therefore seen as unsettling and even threatening. However, constant empowerment through the corrective of the Gospel shall serve as a condition for being rescued from the power of mammon and its destructive bondage of slavery. This understanding certainly opens the possibility of liberation, as opposed to oppression by neocolonial market mechanisms. For the people at the grassroots, Luke’s

Luke’s economy not only goes beyond all the concepts of “utility” or “disutility” but also establishes transformation across categorical dominant boundaries of “self” and “other.” In the

From a perspective of the minjung-messiah, however, the Gospel of Luke does not condone interested relations, but rather fosters (comm)union - such as “hugging” and “kissing” with the “prodigal.” Hence, the disappeared will be found, the missing welcomed home. For an East Asian global reader, the “prodigal” remains a marker of the

Neither an “atomized” self nor an “ideal” whole can be viable “in a salutary and vivifying manner” without the Other(s).37) In view of the Gospel, it is pure formalism to imagine that otherness, heterogeneity and marginality are unqualified political/economic benefits. Without the imperial-colonial drive to “atomized singles” (e.g., the older brother) or “constrained wholes” (e.g.,

This calls into existence the people of God as

30)E. S. Fiorenza, “Changing the Paradigms: The Ethos of Biblical Studies,” in Rhetoric and Ethic, 31-55. 31)Thomas L. Friedman, “The End of the Rainbow,” New York Times: 29 June 2005. 32)See the earlier discussion of Segovia (2000); Meeks (1989). 33)Rohun Park, “Revelation for Sale: An Intercultural Reading of Revelation 18 from an East Asian Perspective,” The Bible and Critical Theory 4 (2008:2): 25.1?25.12. 34)In this regard, Dussel notes that “Once capital is absolutized - idolized, fetishized - it is the workers themselves who are immolated on its altar, as their life is extracted from them (their wages do not pay the whole of the life they objectify in the value of the product) and immolated to the god. As of old, so today as well, living human beings are sacrificed to mammon and Moloch.” Ethics and Community (Maryknoll, NY : Orbis Books, 1988), 260. 35)It is here worth quoting from the poem of Wallace Stevens: “We are not our own. Nothing is itself taken alone. Things are because of interrelations and interconnections.” Opus Posthumous: Poems, Plays, Prose, ed. Milton J. Bates (NY: Vintage, 1990), 163. 36)Deleuze defines transcendence by means of the dative relation. Between Deleuze and Derrida, eds. Paul Patton and John Protevi (London; New York: Continuum, 2003), 81; see Claire Elise Katz and Lara Trout’s Emmanuel Levinas: Levinas and the History of Philosophy (London; New York: Routledge, 2005), 179. 37)Dwight N. Hopkins’s insightful discussion of humanity, Being Human (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2005), 82.

In the Gospel of Luke, human misappropriations bring about scarcity. For those who monopolize resources and exclude those who do not have property from the

Hence, Luke unabashedly presents a whole range of work options: renouncing riches for the poor, lowering debts (16:5-7), lending without expecting return (6:34-35), putting oneself at others disposal both with service and riches by and providing hospitality (8:1-3; 10:38-42), inviting the poor and the social outcasts (14:15-24), offering (21:1-4), wasting for love (7:36-50; 15:22-32), disposing half of one’s assets and also making restitutions (19:1-9), and communal ownership (Acts 4:32-37). This sort of variety in the Lukan corpus precludes the formulation of any single norm as to “the” Lukan ethic about property and wealth. Rather Luke commends and even celebrates all the options by inviting the people of God, be they “children” (16:25), “friends” (12:4, 22; 16:9), or “disciples” (14:26; 16:1), to the

Luke’s political economy, therefore, pertains to cultural, ontological, and theological consciousness. All the parables we have observed occur in Luke’s unique so-called Travel Narrative. Jesus’ journey to Jerusalem, which inspired Chang Il Tam, remains a central section of Luke. Luke describes Jesus as one constantly on the road. At the heart of this journey are the invitations to the people of God to live in the present being shaped and transformed by the dreams and visions, which go beyond simply a concept of “utility,” or “disutility,” while affirming communion and liberation. As such, reading the Gospel from the present may give us pause, but does Luke’s narrator also want to stop us in our journeys? Notice that the parable is still open-ended!

Thus far, my reading of the Gospel has not taken place beyond perspective and contextualization. While the exclusive focus on the text has long obscured the ways in which cultural context and social location inform the subjectivity of interpretation, foregrounding cultural/social location puts readers in a better position to recognize the ways in which their location informs and reforms their understanding of the text. Bringing an interpreter’s context to critical understanding also enables interpreters to “see” more clearly when their interpretations contribute to oppression or to justice - that is “ethical dimensions and ethical consequences.” 39)

Hence, from an East Asian global perspective, I have employed the marginality of the colonized as a cultural text that creates new horizons with biblical interpretations. I have since attempted to read the text anew by way of discursive reflections and conscientizations through a struggle between competing visions and ideologies.40) In the process, meaning has been produced through complex modes of interaction involving both text and reader; the meaning is, for sure, not value-neutral, not autonomoushermeneutical, and not authoritative-dominant.

The alternative construction of Luke challenges our own convictions and empowers us to confront the economy in our worlds. We cannot be inactive in this endeavor since without our collective self-reflection of and engagement in the political economic institution we will remain its victims. As “the child grew and became strong in spirit” (1:80), the readers need to be deeply connected to, and grow out of the irrepressibly inspired convictions that imagine the world that is not and draw them into radical visions of the beyond. Since the experience as such cannot be transmitted directly - because it is not an idea or doctrine that one can understand - one only experiences it in a true experience of communion with the Others, in which one determines the very character of political economic existence.

It is, then, a relocation into the imaginative landscape of God’s

38)Sondra Ely Wheeler, The New Testament on Wealth and Possessions: A Test of Ethical Method (Ph.D. Dissertation: Yale University, 1992). 39)Rhoads (2004): 55. 40)On this point, Segovia states that: “[C]ritical situation envisioned is not necessarily one where ‘anything goes,’ since readers and interpreters are always positioned and interested and thus always engaged in evaluation and construction: both texts and “texts” are constantly analyzed and engaged, with acceptance or rejection, full or partial, as ever-present and ever-shifting possibilities.” Interpreting Beyond Borders (2000), 47; see also the discussion of E. S. Fiorenza. She asserts that: “In and through such a critical rhetorical process of interpretation and deliberation religious and biblical studies are constituted as public discourses that are sites of struggle and conscientization. The transformation of biblical studies into such a theo-ethics of interpretation calls for a rhetorical method of analysis that is able to articulate the power and radical democratic visions of well-being inscribed in biblical studies.” E. S. Fiorenza, “Changing the Paradigms: The Ethos of Biblical Studies” in Rhetoric and Ethic, 55.