It has now been more than a decade since Korean1 popular culture has made a massive inroad into East Asia and, subsequently, other Asian countries. The mass media and concerned scholars have given the appellation of “Korean Wave” (

The surge of popularity of Korean popular culture in these countries has drawn “anti-

Despite the suspicion that the Korean Wave is only a temporal and isolated trend like a short-lived fashion, it has not only survived but expanded to more diverse and wider products and to countries beyond East Asia. Thus, a major Korean newspaper recently featured an article entitled “Evolving ‘

Since a Chinese newspaper coined the term

After more than a decade since its inception, the question of longevity, or the future, of

Specifically, this study tries to answer the following questions. First, is

1Korea in this paper denotes South Korea only. 2In this paper, I use the term Hallyu to mean both the flow and popularity of Korean popular cultural products, especially media contents, in other Asian countries and beyond, as well as exported Korean popular cultural products themselves. 3Korean news media recently reported that a Korean idol group concert in Paris was sold out within 15 minutes and a demonstration asking for another concert was staged in front of the Louvre museum by ardent fans that could not get tickets (KBS News, May 2, 2011).

Theoretical Approaches to and Empirical Works on Hallyu

One of the prominent theories that inform existing studies on

There are diverse models and dimensions of globalization. A prominent model is the political-economic one, which explains globalization in terms of changing conditions of capitalism. According to James Mittelman (2000), for example, the recent phase of globalization started as a response to the deep recession in Western countries in the 1970s. In order to get over the economic crisis, new strategies including restructuring, deregulation, privatization, and enhanced competitiveness, which have been elevated to the neo-liberal ideology, were adopted. In addition to the transnational ideology of neoliberalism, Ramesh Mishra argues, hegemony of the Anglo-Saxon form of capitalism has also been extended and consolidated in this process (Mishra 1999, pp. 7-8). In this model, economic factors, or more precisely the logic of capital, are foremost in importance for the modern phase of globalization, and they subsume all other aspects of globalization.

But, globalization is a complex term involving many dimensions, including not only economic and political but also social and cultural ones. This study is specifically concerned with cultural globalization, the contemporary process of which has been driven by establishment of new global cultural infrastructure, the rise of Western popular culture, the dominance of multinational culture industries, and an increase in cultural exchange and interaction across national borders (Held et al. 1999, p. 341).

Cultural globalization is often associated with the notion of imperialism, which is regarded as its earlier form (Tomlinson 1991; Schiller 1979; Crane 2002; Curren and Park 2000). According to this conception, cultural imperialism refers simply to cultural domination, or to the imposition of a particular nation’s beliefs, values, knowledge, behavioral norms, and style of life by core nations over peripheral ones. It emerged in the 1960s as part of a Marxist critique of advanced capitalist cultures that emphasize consumerism, hedonism, and mass communication.

Cultural imperialism has been criticized on many grounds. For one, cultural flow is not necessarily one-way, from the core to the periphery, but multi-directional, sometimes flowing from the periphery to the core (Berger 2002; Crane 2002). Critiques also indicate that the theory fails to acknowledge the significance of local resistance to imperial culture, especially the rise of nationalism in opposition to globalization, and that it ignores the processes of negotiation, adaptation, and indigenization on the part of receiving cultures (Curren and Park 2000; Robertson 1994). Thus, it is often the case that, instead of a global, uniform culture as a result of cultural imperialism, local indigenous cultures are rediscovered, and hybrid cultures are created (Appadurai 1990; Nederveen Pieterse 1995).

Existing works on

Some critical observers view

In a similar vein, Hyun-Mee Kim (2003) explains the

These political-economic approaches, whether critical or not, tend to emphasize structural or institutional backgrounds for the rise of

Thus, some researchers look to cultural aspects of

But this cultural commonality approach is obviously not enough to explain the

In a similar vein, the concept of cultural discount emphasizes that distinctiveness of a country’s cultural products in terms of values, believes, and style may hinder their acceptance by consumers in other countries. Iwabuchi’s account of Japanese cultural products exported to other Asian countries is a typical example. He contends that Japanese cultural producers are careful to remove “Japanese odor” from their products so as not to induce resistance from foreign audiences (Iwabuchi 2004). In a sense, Korean cultural products, which have indigenized Western popular culture that resulted in a hybrid culture blending traditional Asian and modern Western cultures, provide less cultural discount to Asian audiences who want to enjoy modern Western popular culture but, at the same time, are reluctant to accept the latter outright due to ideological and other reasons (Gim 2007; Hong-xi Han. 2005; Lee et al. 2006; Lee 2006; Shim 2006; Yun 2009).

The thesis of cultural hybridity requests our attention be turned to the tastes of young Asian audiences who prefer modern to traditional, and Western to Confucian, cultural products, because most of them grew up in a more prosperous period in history and are in better contact with Western culture due to recent developments in communication and transportation technologies. Some observers note that Korean popular cultural products are unique in that they are mainly Western in form but mostly traditional Confucian in contents (Yun 2009; Shim 2006; Lee 2006). These unique characteristics of Korean popular culture have attracted many young Asian audiences who are fond of cultural products of modern flavor but are uneasy with Western cultural contents. Unlike Japan where

The reception theory or the cultural approach to

From the above review of theories and empirical works on

Two kinds of data are utilized in this study. One is statistical data with regard to cultural markets and culture industry in Korea, most of which are produced by government agencies and research institutes. Data to be analyzed include the size as well as changes over time and variations among countries and genres of Korean cultural products exported to East Asian countries for the past several years. Changes in cultural policies and market situations both in Korea and other East Asian countries are also examined. Resulting data will provide evidence for the continuity and transformation of

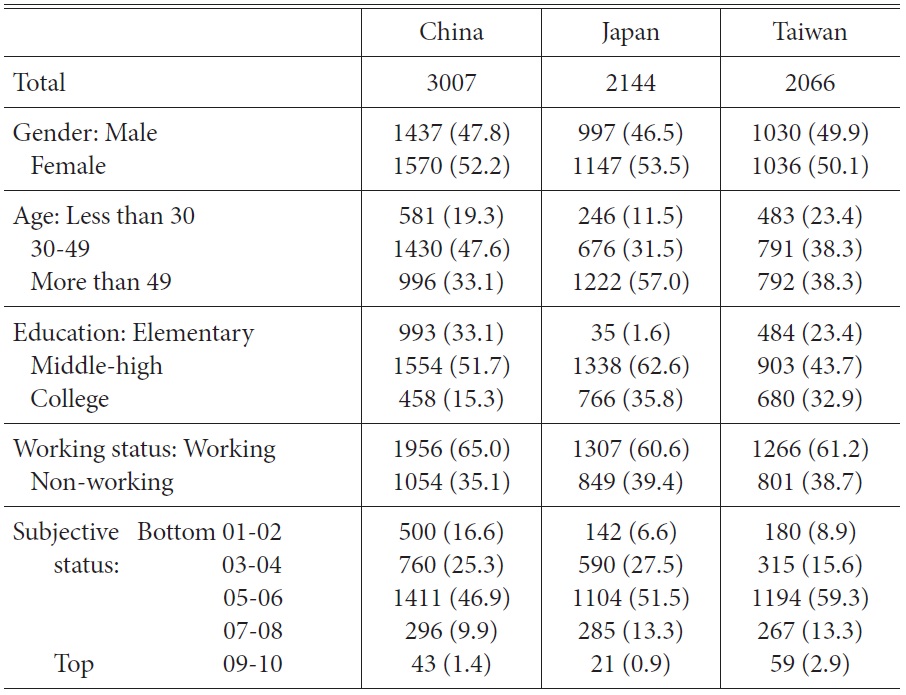

The second, but very important, source of data in this study is the 2008 EASS (East Asian Social Survey). EASS is a national sample survey conducted annually in four East Asian countries of China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan to collect data on various aspects of peoples’ lives, opinions, and attitudes, and the 2008 EASS was conducted in 2008 in each of the four member countries. A brief description of the four national samples is given in table 1. Each member country has its own questionnaire, but includes a special module that applies to all four members. The special module for 2008 EASS is “Culture and Globalization in East Asia,” which contains questions regarding consumption of foreign cultural products, cultural values and tastes, social distance and social networks, attitudes toward globalization, and so on. This study analyzes responses to the questions in this special module in China, Japan and Taiwan.

The dependent variable is the consumption of Korean TV dramas by respondents in China, Japan, and Taiwan. It was, after all, Korean TV dramas that initiated and sustained

There are three types of independent variables, reflecting the three major approaches to

The second independent variable, social proximity, is also a composite variable consisting of three items measuring social distance to Korean people. This is a proxy variable for the cultural proximity thesis. Because the cultural proximity theory is limited in its application and other types of proximity such as racial proximity are proposed in explaining the popularity of Korean popular culture in Asia (Kim 2007), a more general measure of proximity seems to be necessary; social proximity can be an alternative. For this measure, respondents were asked to answer ① “yes” or ② ”no” to the following three questions: (1) Can you accept Korean people working alongside you at your workplace? (2) Can you accept Korean people living on your street as neighbors? (3) Can you accept Korean people as close kin by marriage? The social proximity variable is the sum of the scores for these items.

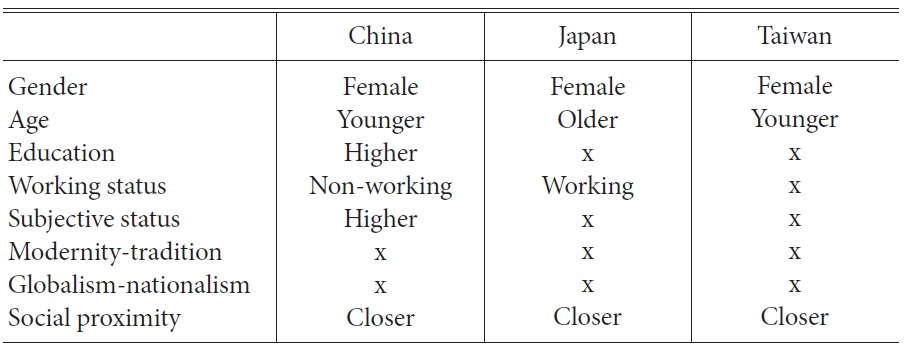

[Table 1] Demographic and Socio-economic Characteristics of the Samples (%)

Demographic and Socio-economic Characteristics of the Samples (%)

The third independent variable is the modernity-tradition variable that which represents the modernity theory. This variable is measured by six items, which were answered on a seven-point scale from ① “strongly agree” to ⑦ “strongly disagree.”. The six items are as follows: (1) It is not desirable to oppose an idea which the majority of people accept, even if it is different from one’s own. (2) One should not express one’s complaints about others in order to have a good relationship with them. (3) When hiring someone at a private company, it would be better to give the opportunity to relatives or friends even if an unacquainted person is more qualified. (4) I feel honored when people who come from the same town play an important role in society. (5) A subordinate should obey superiors’ instructions even if s/he does not agree with them. (6) It is better to let capable leaders decide everything. This variable is also a composite variable summing the scores for the six items.

Finally, control variables include gender, age, education (highest level of education attended), working status (working versus non-working), and subjective social status (subjective position on a ten-point scale) representing respondents’ demographics, and socio-economic characteristics (cf. table 1 for a description of these variables).

For structural and institutional backgrounds on

Survey data are analyzed using such statistical methods as cross tabulation and regression analysis. For multivariate analysis, the dependent variable is converted into a dummy variable by combining “often” and “sometimes” as 1, and “seldom” and “not at all” as 0. The three independent variables are all composite variables consisting of more than one item. In order to simplify the procedure, actual scores of the items for each variable are added to produce the score for the composite variable.4 For the multivariate relationship between the dummy dependent variable and the composite independent variables, logistic regression analyses are utilized.

Structural and Institutional Bases of Hallyu

It was, above all, the development of the Korean popular cultural market and industry, together with globalization and expansion of the Asian market that made

Korean cultural market had been closed to foreign input for quite a while, and its culture industry had been very much underdeveloped due to the government’s strict control of cultural flow and cultural market since the liberation from Japanese colonial rule in 1945. The Kim Young Sam government (1992-1997), the first civilian government since the military dictatorship of two-and-a-half decades, took neoliberalism as its basic ideology and liberalized Korean economy by joining the WTO in 1995 and the OECD in 1996. This neoliberal economic policy is at least partly responsible for the 1997 economic crisis, which brought about the IMF intervention and liberalization policies. Subsequent Kim Dae Jung government (1998-2003) had no choice but to follow the IMF-mandated structural reform which emphasized liberalization, deregulation, and privatization (Yang 2007, p. 184).

As part of liberalization, Korean cultural market began to open to foreign influence. Allowing Hollywood film distributors to do business in Korea in 1988 was probably the first foreign intrusion into the Korean cultural market, although foreign films were screened by local distributors within the limit of certain quotas set by the government even before this event. Since the mid-1990s when cable television services started, the number of television channels has greatly expanded, followed by rapid increase in importation of foreign programs. Ban on importation of Japanese popular culture, which had been imposed for more than five decades, has been lifted step by step since 1998. These are a few of the events that have made the Korean cultural market wide-open, resulting in its globalization and enhanced competitiveness (Shim 2008; Yang 2007).

Korean government also realized and emphasized the economic value of the culture and media industry. The government has, since the early 1990s, supported the culture industry by establishing the Culture Industry Bureau for the first time in the Ministry of Culture and Tourism in 1994 and by enacting the Motion Pictures Promotion Law in 1995, which encouraged big corporations (

In addition to these government actions and market changes, the dramatic expansion of communications and information industries, their extensive penetration into everyday life, and people’s greater concern with quality of life as a result of improvement in life conditions have contributed greatly to the development of culture industry.5

Recent changes in other Asian cultural markets are no less important for the rise of

Japan has a unique place in East Asia because it is the first modernized country in Asia and the only country that colonized many parts of the region in modern times. Because of these facts, at least in part, it has always looked to the West and considered itself as “being in Asia but not part of Asia” (Chua 2008, p. 80) or “always in and yet always above Asia” (Iwabuchi 2004, p. 150). This attitude of “Japan is forward and the rest backward” is probably responsible for its reluctance to actively engage in a cultural relationship with other Asian countries. Japanese popular culture, however, has been popular since 1970 in a few East Asian countries such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore. At first, audiences of Japanese popular culture in these countries were limited to a minority of enthusiasts but became widespread in the 1990s, especially among young people. At that time, Japanese culture industry, which had been mostly inward-looking because its domestic market was large enough to support it, began to search for overseas cultural markets. Paradoxically, the popularity of Japanese popular culture began to wane by then (Iwabuchi 2002).

Japan’s cultural relationship with Korea had been strained for a long time because of the aforementioned ban on importing Japanese popular culture due to Korea’s experience of colonial rule by Japan for 35 years. However, even before the opening-up of Korean cultural market to Japanese cultural products, they were smuggled in by enthusiastic fans and copied by Korean cultural producers, most notably television programs. Concurrently, a few Korean popular singers gained fame in Japan even before 1998, and some of the Korean films, such as Shiri, were well-received by the Japanese audience in early 2000s (Kyeong-mi Shin 2006). A series of events including the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games and the 2002 FIFA Korea-Japan World Cup also helped change Korea’s image in Japan and the otherwise sore relationship between the two countries to a friendly one (Mori 2008).

Above all, it was the television drama series

The People’s Republic of China had been a secluded communist country since 1949, but it made a drastic transformation of its communist economy into a market economy under Deng Xiao Ping’s “four modernization policy” in the 1980s. The drive towards more liberalized economic reforms has not only geared to a great expansion of mass media but also has been translated into a gradual commercial view on media policy. Competition among mass media in attracting audiences has become keen, which has led them to adopt such measures as making more of entertaining and profit-making products, importing them from abroad, and co-producing with non-Chinese finance (Stockman 2000, pp. 169-70).

In the early 1990, the film and television industries were liberalized, and cable and satellite television networks grew rapidly, due in part to the development of media technologies and also in part to popular demand for leisure from economically improved audiences. Satellite television networks have made broadcasts from Taiwan and Hong Kong available to Chinese viewers, which resulted in the state losing its monopoly over broadcasting. Subsequently, the state changed its policy on television production from “literature and arts” to “entertainment,” and the media industry took profit maximization as its prime motive (Leung 2008, p. 58).

The burgeoning of local television stations and the scarcity of local programs due to low production capacity have made Chinese television stations turn to foreign programs which are cheaper than local productions and which often provide ideas and formats to be adopted by local producers (Leung 2008). In fact, there have been a flow of media contents among ethnic Chinese countries, i.e., Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and China. As well, a study reports that Japanese television programs were popular among Chinese television viewers in the 1970s and 1980s, but Japanese programs have become less popular and consumed by only a fragmented young audience in the 1990s (Iwabuchi 2002, pp. 123-37).

However, liberalization of media in China does not mean total freedom of speech such as enjoyed by the media in the West. Television production is still heavily regulated and censored by such government agencies as the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television.6 Chinese government is especially sensitive towards “foreign elements,” which is regulated by such policy measures as the quota system that limits foreign programs to less than 20 percent of the total broadcasting time and restriction on broadcasting foreign programs during prime time (Leung 2008).

Thus,

In Taiwan, cable channels make up a major part of the television industry from the start, supplementing the three free-to-air stations whose signals could not be received by some of the country’s population. Since the late 1970s, illegal cable television stations have burgeoned rapidly to meet the audiences’ demand for entertainment programs which the three terrestrial television stations cannot provide due to the authoritarian government’s strict control over them. Since Taiwan became an independent state that seceded from mainland China in 1949, the KMT (The Nationalist Party) government had run the country under martial law, and every aspect of society was tightly controlled by it.

The government tried to stop the illegal cable channels, but in vain. Or it may be better a description to say that the Taiwanese government took a hands-off policy on television, imposing loose restrictions on ownership, number of channels, number of foreign programs, and so on. Since the 1980s, democratic and liberal movements have sprung up as a result of strong economic growth and market liberalization, and the government finally lifted martial law in 1987. Under pressure from the US, a new copyright law was passed in 1992 and a new cable television law in 1993, which legalized the cable television stations and allowed them to broadcast foreign programs up to 80 percent of the air time. It was estimated that more than 80 percent of the Taiwanese audience watched cable television channels, which numbered more than 120 as of the early 2000s (Lin 2006; Kim 2003).

As a result of these changes in the media industry, Taiwanese cable television stations began to import a large number of foreign programs in the 1990s. The increased number of channels demanded equally large number of programs, while the share of each channel in the market decreased. For example, a study reported that the share of the top ten programs in the viewership ratings amounted to only 4 percent. Thus, in order to make a profit, channel providers had to resort to importation of foreign programs that are relatively cheaper than domestic production, but of high quality. During the period of illegal cable system, imported television programs were mostly from Hong Kong, China, and Japan, from which 62, 54, and 61 dramas were imported, respectively, for the period of 1993-1999 (Lin 2006). Broadcasting of Japanese dramas increased rapidly after the Taiwanese government lifted the ban on importation of Japanese cultural products in 1993, which was imposed due to its colonial history. The audiences of Japanese television dramas were mostly young people who seemed to have cultural tastes of a modern flavor. According to an expert on Asian popular culture, “Taiwanese consumption of Japanese TV dramas … is due in part to an emerging sense…of coevalness with the Japanese, that is, the feeling that Taiwanese share a modern temporality with Japan” (Iwabuchi 2002, p. 122).

Even after the deregulation of the media industry, however, Taiwanese cable television providers showed little interest in Korean dramas due to a couple of factors in addition to language and cultural barriers. One factor is political: The long-standing friendly relationship between the two countries was abruptly ended in 1992 when Korea established formal diplomatic relationship with People’s Republic of China (PRC). The other is cultural: Taiwanese consumers perceived Korean cultural products as backward (Lin 2006; Kim 2003). This situation changed since the late 1990s, when GTV, a cable channel which specialize in domestic programs mainly for older rural housewives, began to import Korean dramas because the latter were much cheaper than domestic ones and of high quality. The imported Korean dramas were “domesticated” before broadcasting, with Chinese dubbing and subtitling, inserting Taiwanese pop songs at the beginning, replacing OSTs with Taiwanese songs, and adapted translation (i.e., the original version of the drama was reconstituted in accordance with Taiwanese cultural system) (Hwang 2007; Kim 2003). GTV did not even label these imported Korean dramas as Korean dramas.

It was in 2000 that

4See appendix for factor analyses results for these variables. 5See Shim (2008) and Yang (2009) for a detailed account of these changes. 6This agency recently sent out directives to all major television stations not to broadcast entertainment programs for three months but to broadcast only those dramas and documentaries which depict or propagate Chinese Communist revolution and socialist ideology in order to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the foundation of the Chinese Communist Party (Chosun ilbo, May 6, 2011).

Due to these changes in the neighboring countries as well as in its own structural and institutional conditions, Korean culture industry grew rapidly. Total sales of the Korean culture industry had grown 21 percent per annum for the period of 1999-2003, compared with the GDP growth rate of 6.1 percent for the same period. The industry’s growth rate has slowed down since 2003, with an average of 4.2 percent per year for the period of 2004-2008, due primarily to the recent world-wide economic recession (MCT 2003, p. 28; MCST 2010a, p. 19). The publishing industry was the largest in terms of its share in the total sales (35.7 percent) in 2008, followed by broadcasting (18.6 percent), advertisement (15.8 percent), and game (9.5 percent).

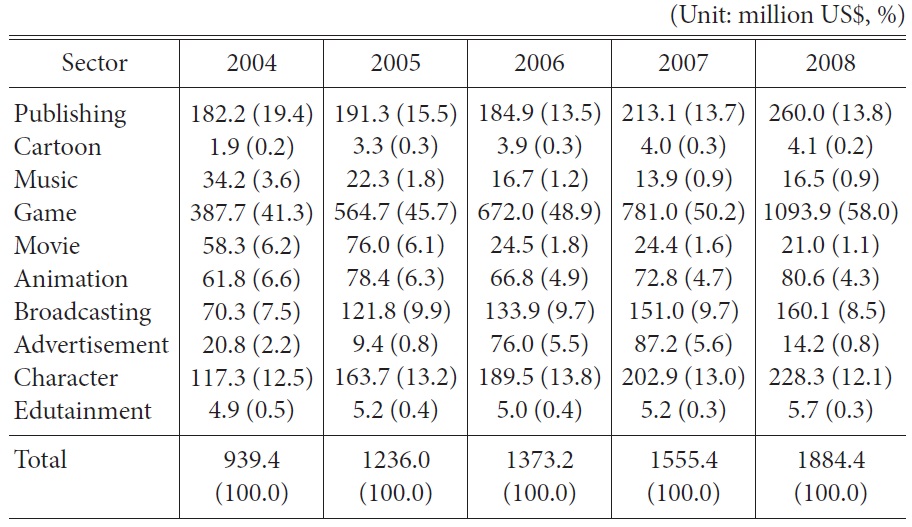

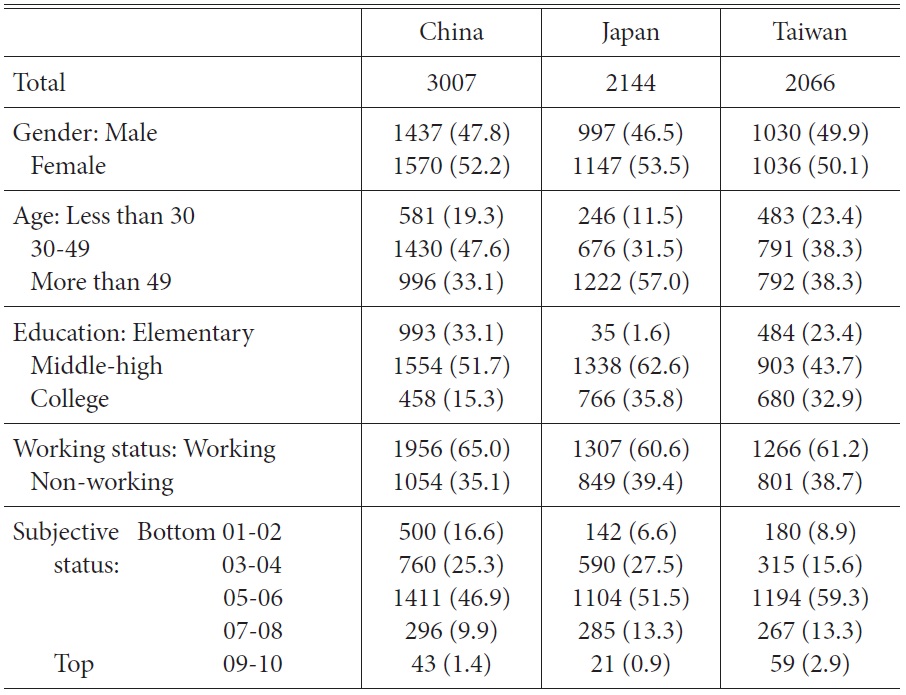

[Table 2] Annual Export of Korean Cultural Products by Sector

Annual Export of Korean Cultural Products by Sector

As globalization swept throughout the world, many of the Asian national markets began, from the early 1990s, to open their doors to foreign cultural flows. The Korean culture industry has gradually participated in the international market, exporting its products in increasingly large numbers firstly to such East Asian countries as China, Taiwan, and Japan and subsequently to the regions beyond East Asia. For example, the total value of exportation of the Korean culture industry was 413 million dollars in 1998, but increased more than twice to 939 million dollars in 2004. It took only four years for the total amount of export to double to 1,884 million dollars in 2008 (see table 2). The digital game industry has led the export drive, comprising 58 percent of total export in 2008, followed by publishing (13.8 percent), character (12.1 percent), and broadcasting (8.5 percent). These four sectors combined account for more than 90 percent of export and have been leading exporters for the past decade, with little variations among them in terms of relative weight. The game industry has always been the leading exporter with its weight increasing, while the share taken up by the publishing industry has been decreasing considerably. The other two sectors seem to remain stable, while the total amount of export by these industries has been steadily increasing.

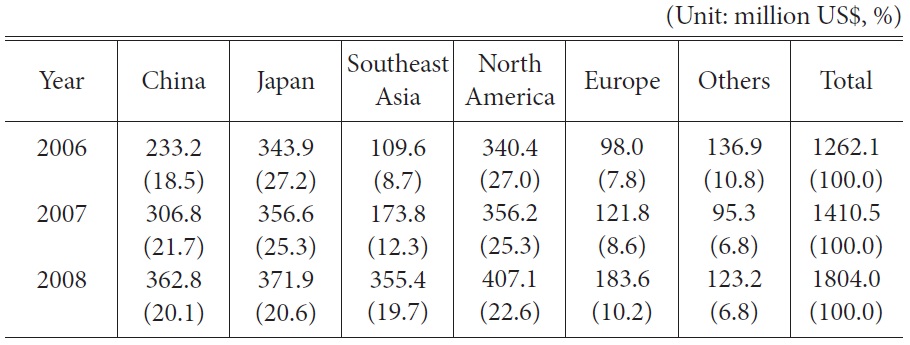

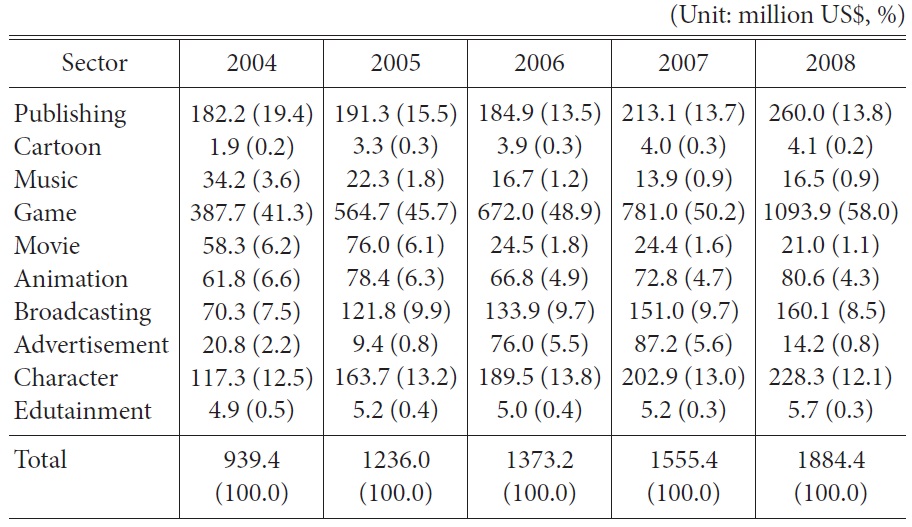

[Table 3] Annual Export of Korean Cultural Products by Destination

Annual Export of Korean Cultural Products by Destination

In terms of destination, more than half of the Korean culture industry export goes to Asian countries, with the distant second being North America. Japan has been the leading importer of Korean cultural products, but China and Southeast Asia are rapidly closing the gap with Japan. As seen in table 3, Japan’s share of Korean export in 2006 was 27.2 percent, while China and Southeast Asia took up 18.5 percent and 8.7 percent, respectively. But these shares changed to 20.6 percent, 20.1 percent, and 19.7 percent, respectively, in 2008. There are also considerable variations among the countries in terms of importation of cultural products. More than 80 percent of China’s total import from the Korean culture industry was from the game industry in 2008, followed by 10.6 percent from the character industry, 5.4 percent from the publishing industry, and 2.2 percent from the broadcasting industry. The figures for Japan were 61.2, 3.4, 6.7, and 17.6, whereas those for Southeast Asia were 68.0, 5.9, 19.5, and 4.8, respectively. Thus, character was the second major import for China besides game, broadcasting for Japan, and publishing for Southeast Asia.

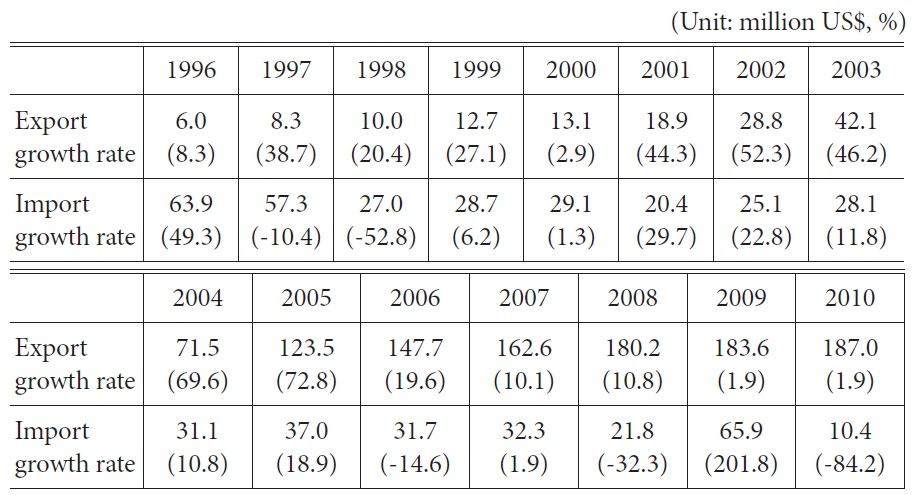

Since

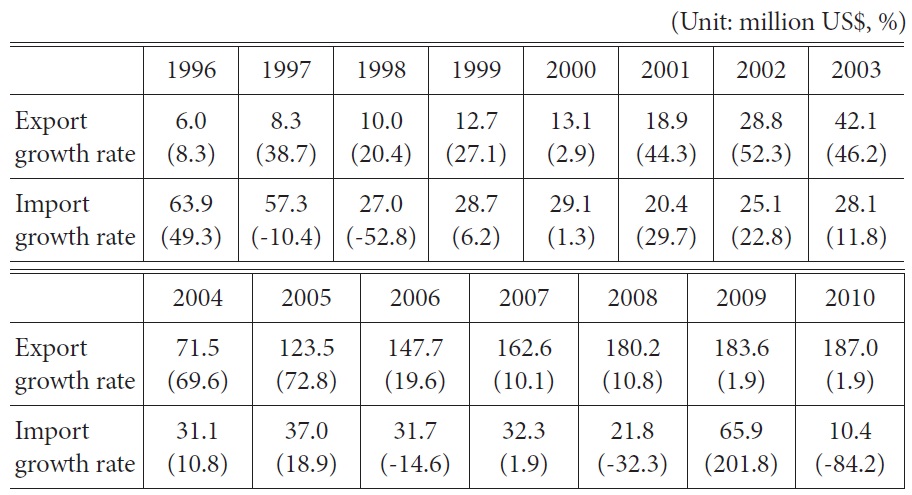

[Table 4] Annual Export and Import of Korean Broadcasting Programs

Annual Export and Import of Korean Broadcasting Programs

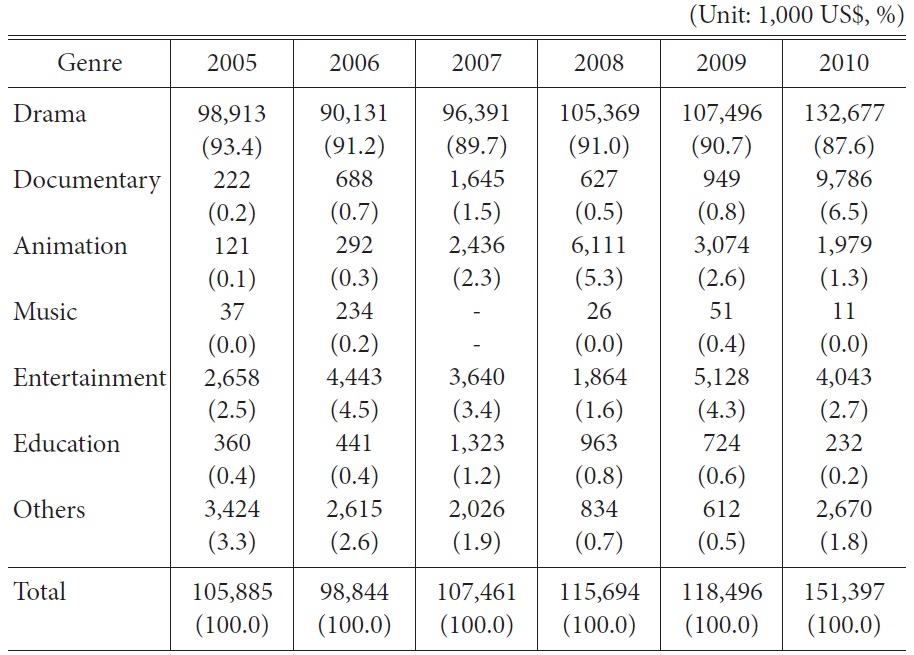

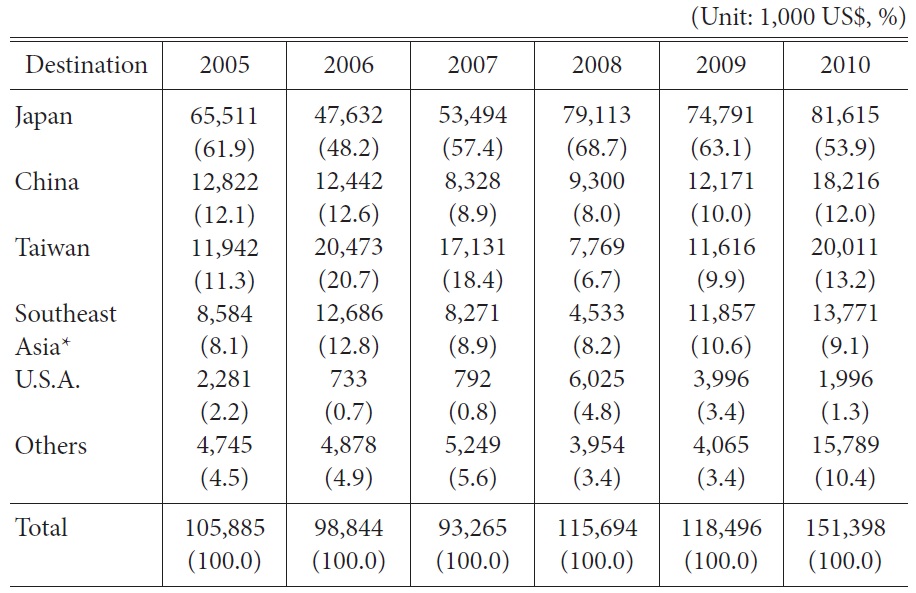

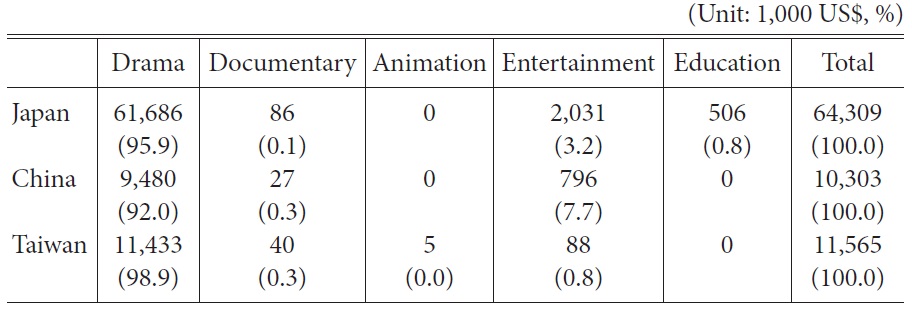

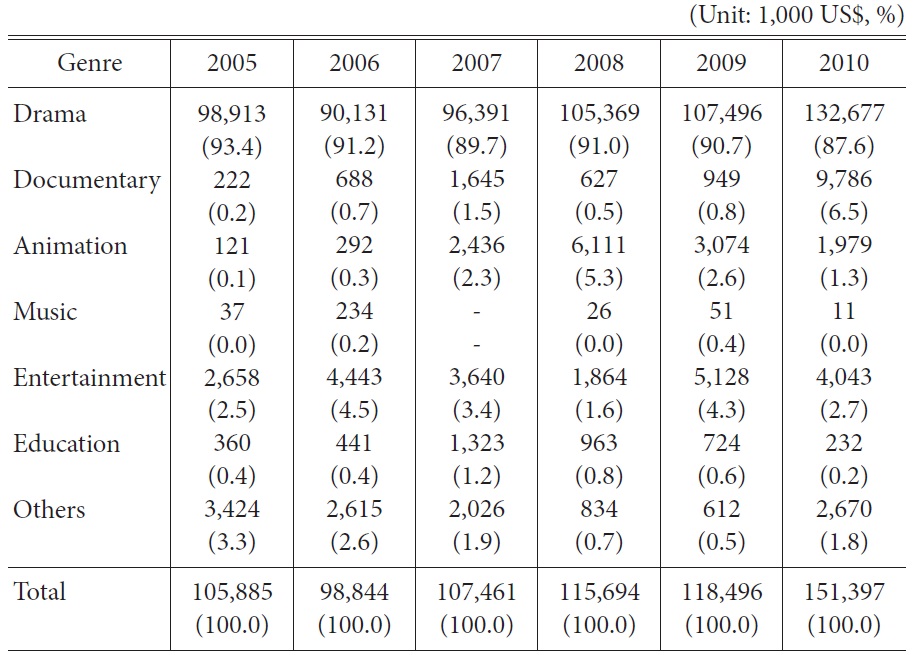

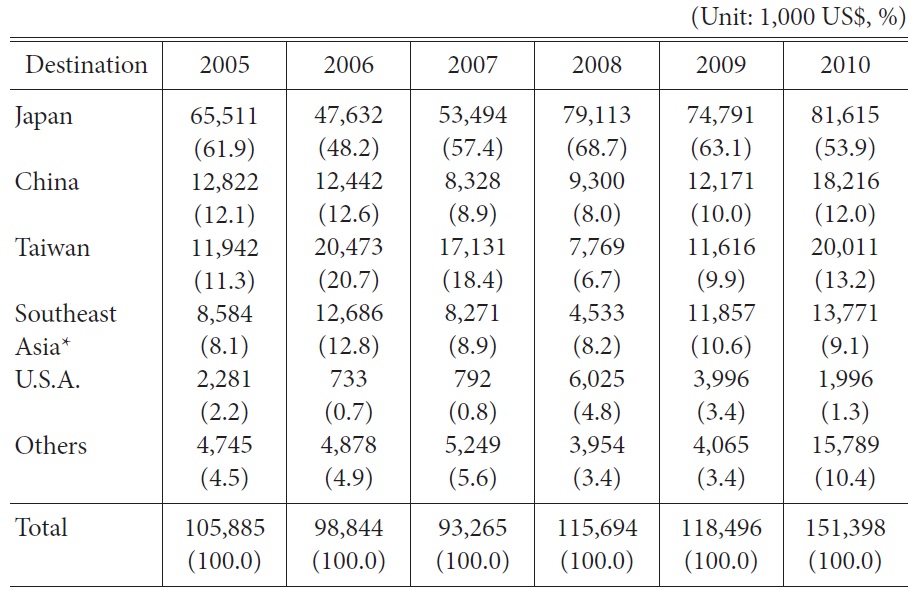

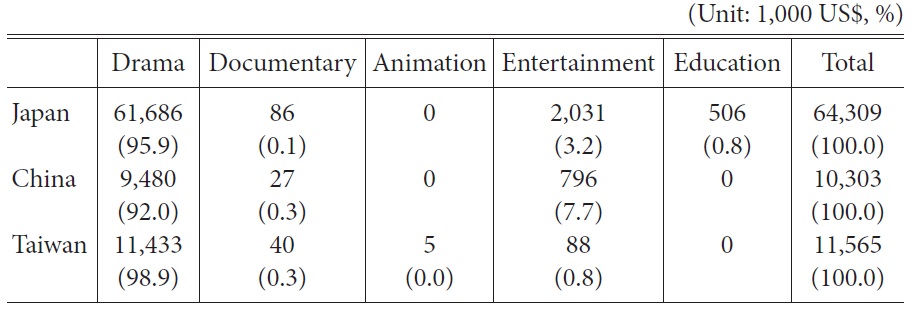

Among the programs exported, drama stands out, accounting for about 90 percent of the total broadcasting export in the past five years. Among other programs, entertainment, animation, and documentary each account for more than 1 percent of the total program export. Export of documentary programs in particular jumped from 0.9 million dollars (0.8% of the total export) in 2009 to 9.8 million dollars (6.5%) in 2010 (table 5). In terms of destination of broadcasting export, Japan is the biggest importer (81.6 million dollars, or 53.9%, of the total in 2010), followed by Taiwan (20.0 million dollars, 13.2%), and China (18.2 million dollars, 12%). But the share of total export for Japan has been decreasing while those for China and Taiwan have been increasing. These three East Asian countries have imported more than 80 percent of the total Korean broadcasting export in the past five years (table 6). Again, drama accounts for more than 90 percent of program import for these three countries, followed by entertainment and documentary in 2009 (table 7).

[Table 5] Export of Korean Broadcasting Programs by Genre, 2005-2010

Export of Korean Broadcasting Programs by Genre, 2005-2010

From the above analysis of aggregate data, we may conclude that the international flow of Korean cultural products has expanded continuously for the past decade, with some fluctuations due to external factors such as economic recession, policy changes, and anti-

[Table 6] Export of Korean Broadcasting Programs by Destination, 2005-2010

Export of Korean Broadcasting Programs by Destination, 2005-2010

[Table 7] 2009 Export of Broadcasting Programs by Genre for China, Japan, and Taiwan

2009 Export of Broadcasting Programs by Genre for China, Japan, and Taiwan

It should also be pointed out that expansion of export of Korean cultural products or broadcasting programs is only partial evidence for the continuing and increasing presence of

Size and Demographic Characteristics of Hallyu Audiences

The

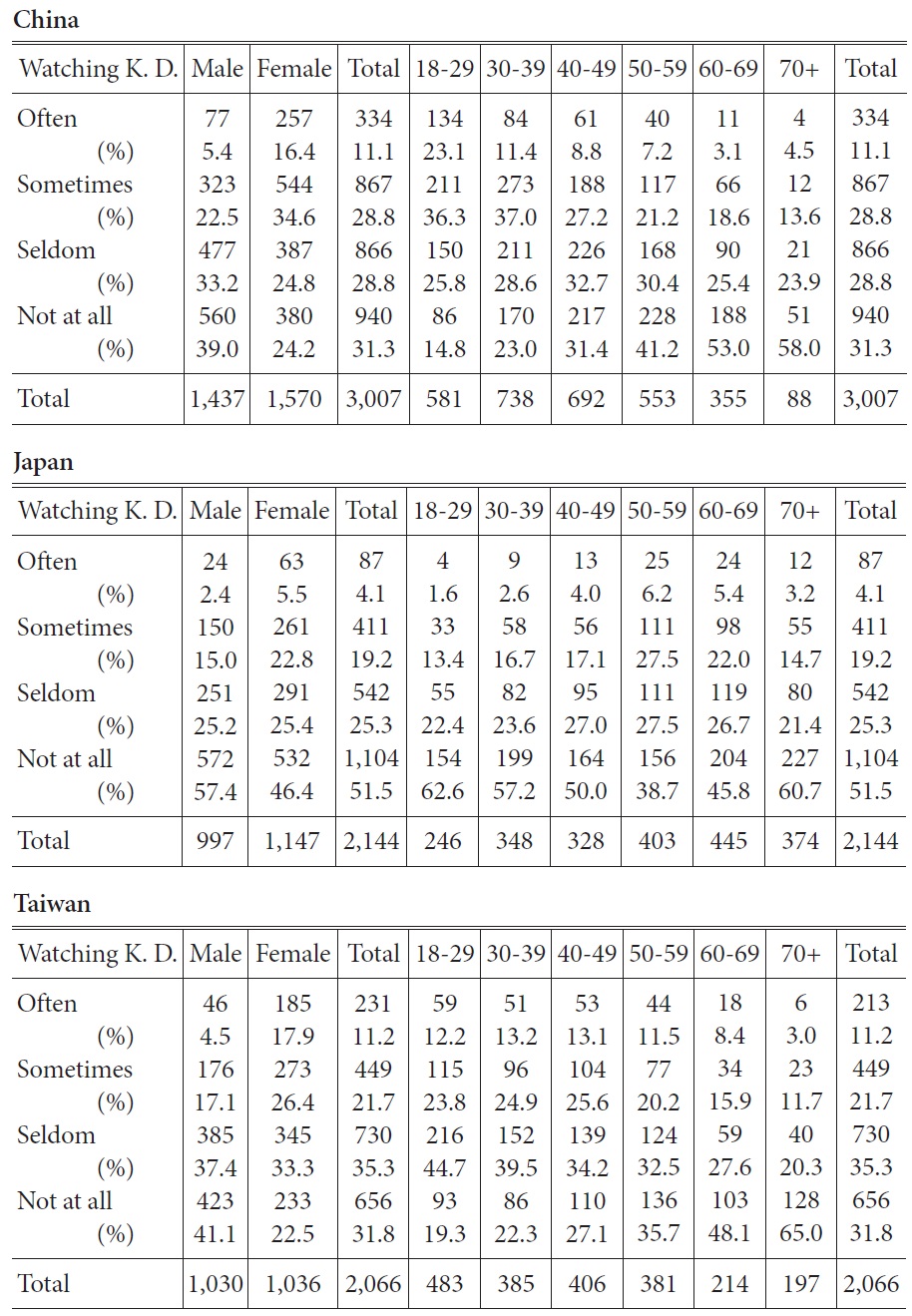

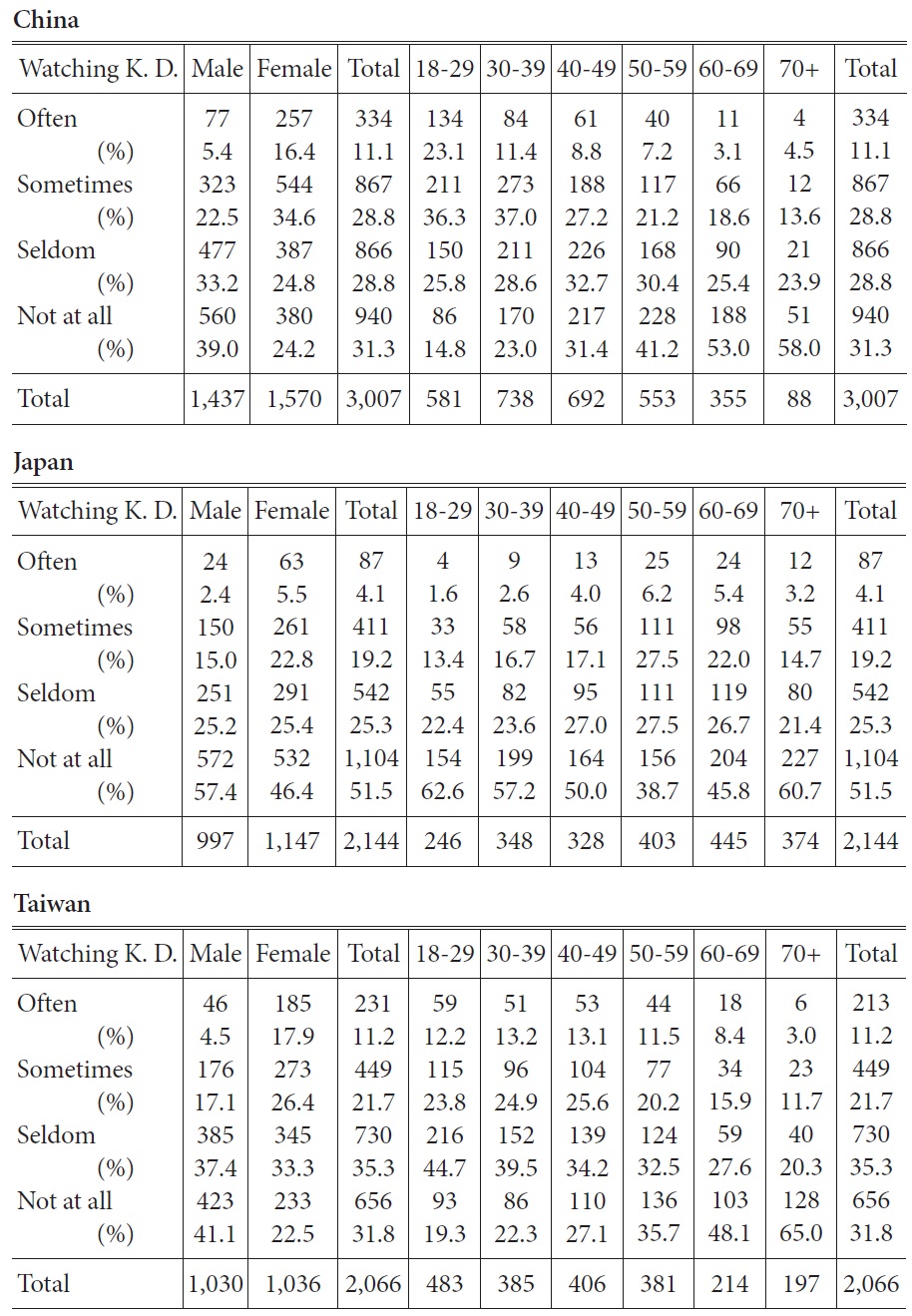

table 8 shows how many people watch Korean television dramas and how often they watch in the three East Asian countries of China, Japan, and Taiwan. Among the three countries, Chinese audiences watch Korean television dramas most, followed by Taiwan and Japan. According to the same table, 11.1 percent of the Chinese sample view Korean dramas often, 28.8 percent sometimes, and 28.8 percent seldom, while 31.3 percent do not watch them at all. Thus, it is safe to say that about 40 percent of the Chinese people are

Thus, if we define

The survey data analyzed here cannot answer the question of whether

Who are the audiences of Korean television dramas? Cultural theories suggest that demographic variables are usually related to cultural tastes. In the case of

Unlike gender, the age pattern of Korean drama fans is not uniform among the three countries. In China, for example, a clear age pattern can be detected; the younger a Chinese, the more likely s/he is a consumer of Korean popular culture. As seen in table 8, 59.4 percent of Chinese who are younger than 30 watch Korean dramas often or sometimes, in contrast to 21 percent of those over 60. In contrast, more than half of older Chinese who are 60 or over never watch Korean television dramas, while the same is true of only 14.8 percent of young Chinese under 30. Taiwanese fans of Korean dramas are little older than those in China. More than 38 percent of the Taiwanese sample in their 30s and 40s and 36 percent of those under 30 may be classified as

[Table 8] Frequency of Watching Korean Drama by Gender and Age Group

Frequency of Watching Korean Drama by Gender and Age Group

Age pattern is not as clear in the Japanese respondents as in the Chinese and Taiwanese sample, however. That is, Japanese fans of Korean popular culture are relatively evenly distributed across age groups. But a slightly larger proportion of older Japanese respondents views Korean television dramas than their younger counterparts. Especially a higher proportion of

The above analysis of the 2008 EASS survey data demonstrates that the three East Asian countries differ in terms of the demographic characteristics of Korean television drama fans. While female respondents tend to watch Korean dramas more often than their male counterparts in all countries, age groups of

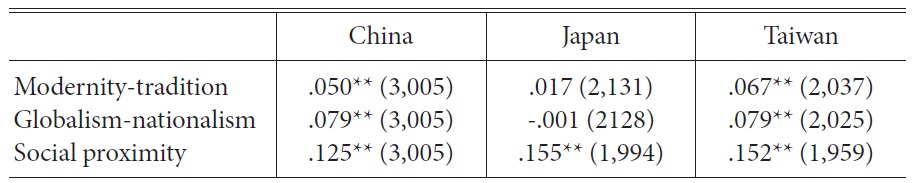

Theoretical and empirical reviews of

The globalism-nationalism scale measures the degree to which respondents are open to outside or foreign political, economical, and social influence. It is hypothesized that the more global a person is, the more s/he accepts or subscribes to

The social proximity variable measures social distance to Korea and is used as a proxy for cultural proximity. This variable is also a composite variable in the form of a scale from 0 to 3. Survey data indicate that Japanese people feel closest to Korea (mean = 1.979), followed by Taiwan (1.934) and China (1.460). Japan and Taiwan are close on this measure, while China is far from the other two countries. Correlation analyses between this variable and the dependent variable shows that they are significant in all three countries. This result may be interpreted as supporting the cultural proximity thesis regarding

The modernity thesis is also a powerful approach to the rise of

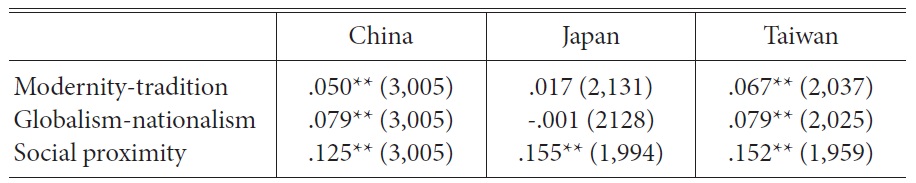

Correlation between Watching Korean Dramas and Each of the Three Independent Variables, Globalism, Modernity, and Proximity

The two-way correlation analyses between the dependent variable and the three independent variables clearly indicate cross-national variations; all three independent variables turn out to be significant predictors of

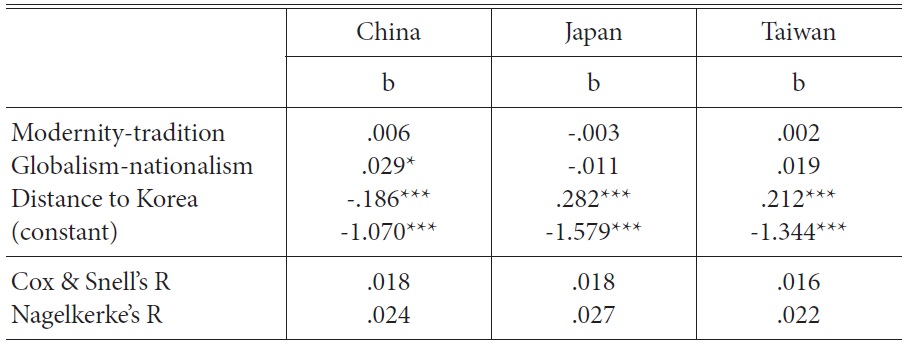

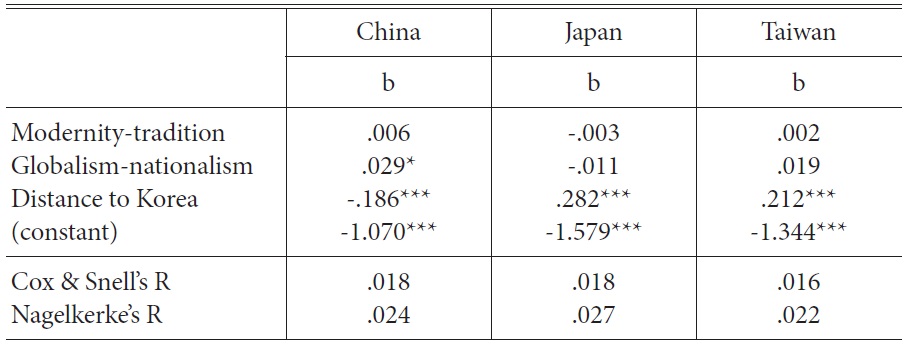

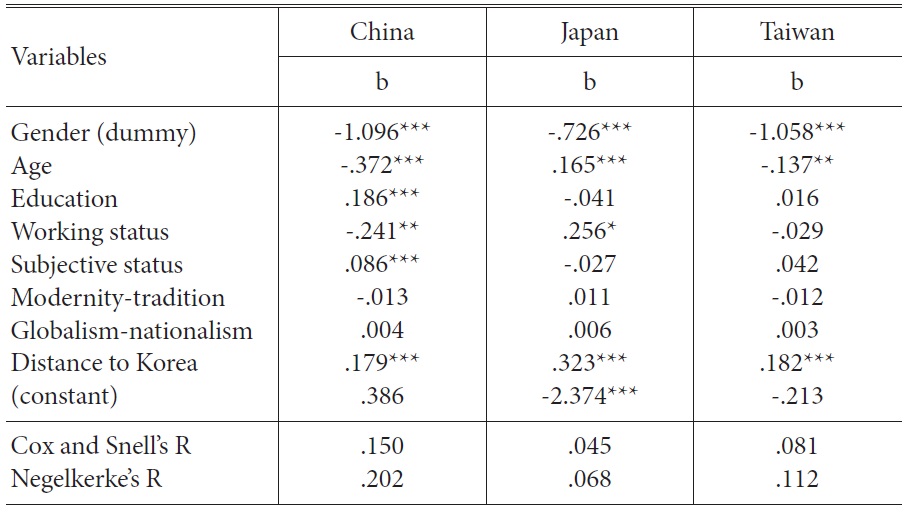

Since independent variables in this study cannot be assumed to be independent from one another, multivariate analyses are necessary in order to detect spurious relationships. For multivariate analyses, dependent variable is converted into a dummy variable by combining (1) often and (2) sometimes into 1 and combining (3) seldom and (4) not at all into 0. A logistic regression analysis for the relationship between the dependent variable and the three independent variables, that is, globalism-nationalism, social proximity, and modernity-tradition, is conducted for each country, the results of which are shown in table 10. Among the three independent variables, only the social proximity variable is significantly related to viewership of Korean television dramas in all three countries, meaning that the closer one feels to Korea, the more likely s/he watches Korean television dramas. The globalism-nationalism variable is proved to be a significant predictor for

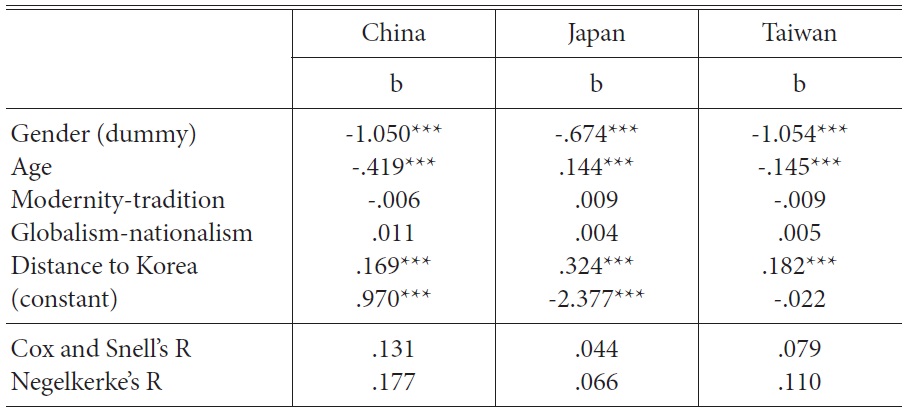

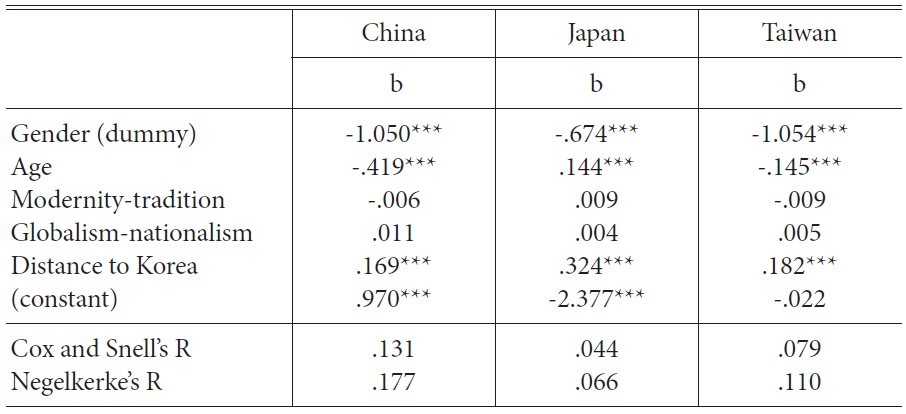

Since demographic variables are proven to be significantly related to

[Table 10] Logistic Regression Results for Watching Korean Dramas (3 Independent Variables)

Logistic Regression Results for Watching Korean Dramas (3 Independent Variables)

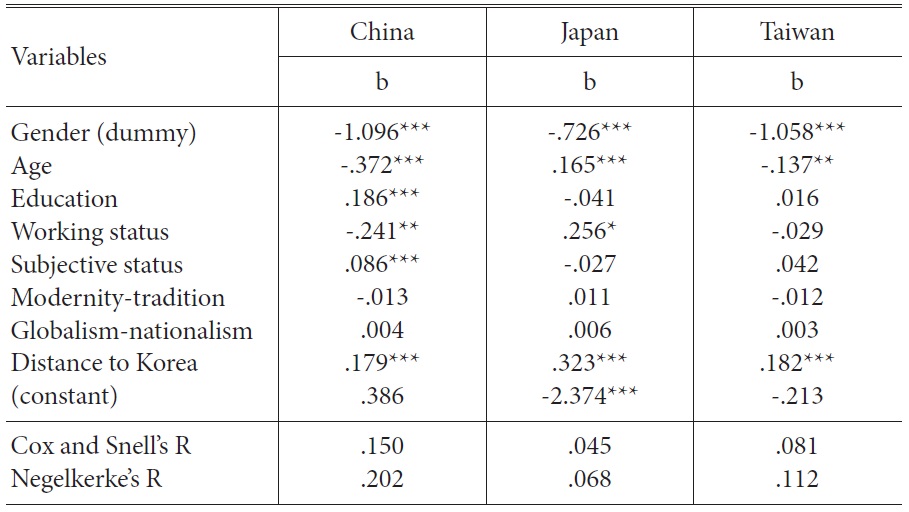

Finally, three more variables representing respondents’ socio-economic status, that is, respondents’ education, working status, and subjective social status, are included in the regression analyses as control variables. Table 12 reports the results of the logistic regression analysis involving eight independent variables. According to the table, respondents’ gender, age, education, working status, subjective social status, and the social proximity variable are all statistically significantly related to viewership of Korean television dramas in China. Thus, a young female Chinese who is highly educated, non-working, high in the subjectively evaluated status scale, and feels close to Korea is likely to be a

The two demographic variables are also prominent in Japan and Taiwan. But in Japan, social proximity turns out to be the most important in accounting for

[Table 11] Logistic Regression Results for Watching Korean Dramas (5 Independent Variables)

Logistic Regression Results for Watching Korean Dramas (5 Independent Variables)

[Table 12] Logistic Regression Results for Watching Korean Dramas (8 Independent Variables)

Logistic Regression Results for Watching Korean Dramas (8 Independent Variables)

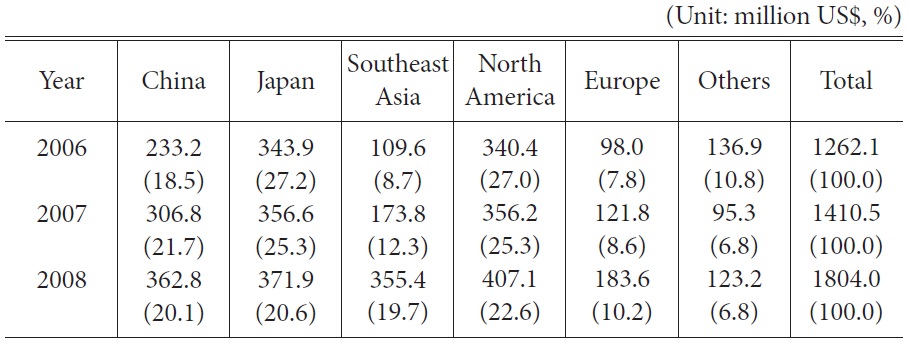

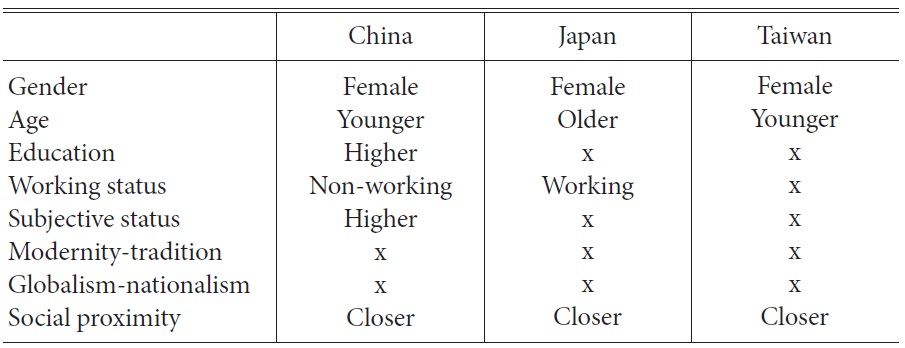

[Table 13] Summary of Multivariate Regression Analyses: Significant Factors for Hallyu

Summary of Multivariate Regression Analyses: Significant Factors for Hallyu

To sum up, the social proximity variable and the two demographic variables turn out to be significant factors for viewership of Korean television dramas in all three East Asian countries. Indicators of socio-economic status are also proven to be important in China, but not as much in Taiwan or Japan. There are other variations among the three countries. Demographic variables turn out to be important in all three countries. This is evident in the comparison of the three coefficients of determination (R²) in tables 10 to table 12. For example, Cox and Snell’s R² for China in table 10 is 0.018, which means that the three independent variables explain 1.8 percent of the total variance in the dependent variable. But R² increases to 0.131 when gender and age are included in the equation (table 11), indicating that the two demographic variables alone contribute to the increase of R² by 0.113. When three socioeconomic status variables are added, the increment of R² is only .019 (table 12). For Taiwan, corresponding R²’s are 0.016, 0.079, and 0.081, which proves that demographic variables have the largest share of R² increment (0.063), followed by the three independent variables (0.016) and socio-economic variables (0.002). A similar result can be seen for Japan: Cox and Snell’s R² for the three independent variables is 0.018, as compared to 0.026, the increment made by the two demographic variables. Korean television dramas seem to attract mostly female audiences—young females in China and Taiwan, and older females in Japan (table 13). The explanatory power of these eight variables is weak in Japan (Cox and Snell’s R², coefficient of determination, is .045), as compared to that of China (0.150) and Taiwan (0.081).

At the same time, other East Asian countries opened their domestic cultural markets to outside inputs. The uncomfortable relationship between Japan and Korea due to the former’s colonization of the latter for 35 years has recently eased, and the inward-looking Japanese culture industry began to look to outside, especially to East Asia, for possible markets. China, the largest socialist country, transformed its economy to a market economy in the 1980s and liberalized the media industry in the 1990s. Intense competition among the numerous television networks forced them to import cheap but high-quality ideologically acceptable foreign programs, of which Korean television programs were one of the most suitable candidates. Taiwan, sharing contemporary historical events with Korea such as Japanese colonization, ideological division of the country, military dictatorship, and late development, escaped from the firm grips of a dictatorial Nationalist government in the late 1980s and saw burgeoning television networks, especially cable television channels, the keen competition among which led to a search for cheaper and well-made programs from overseas. In addition, these East Asian countries share the Confucian cultural tradition, which originated from China, in varying degrees.

Against this backdrop, a few Korean television drama series such as “Dae Jang Geum” in China,

However, analyses of audiences in the three East Asian countries reveal that there are some common factors as well as differences among them. Among the three factors suggested by previous studies, only social proximity turns out to be important for the rise of

But there are differences among the countries. Females are more attracted to Korean popular culture than male audiences in all sample countries; typically, China has the youngest

Thus, although individual indicators of globalism and modernity variables turn out to be spurious in accounting for

It should not be overlooked that the Korean popular cultural products exported to these countries are well-made and of high-quality, however. I think the quality of the products itself is important in accounting for the success of

This is evident in the recent evolution of

Compared to the first stage in which Korean television dramas were the chief promoter of

The initial stage of

In a sense,

7A group of Korean singers belonging to SM Entertainment recently completed a successful world-wide tour, performing in Seoul, Shanghai, Tokyo, Los Angeles, Paris, and New York. The Last performance was on October 23, 2011 in New York. Madison Square Garden; its 15,000 seats were sold out within two weeks (Chosun ilbo, October 25, 2011). 8The following characteristics are evident in an interview with Mr. Sooman Lee, CEO of SM Entertainment Inc., the largest and most successful in this field in Korea (Chosun ilbo, October 16, 2011).