What type of political institutions has been arranged in ending violent civil conflicts and why? In this article I review intellectual debates on consociationalism and the power sharing approach to civil war resolution and formulate three testable hypotheses: an institutional affinity hypothesis, a United Nations (UN) intervention effect hypothesis, and a conflict characteristics hypothesis. These hypotheses are empirically tested with thirty-six cases of negotiated settlements of civil wars in the post-Cold War period. The empirical results present that parliamentarism has greater institutional affinity with executive power sharing than other types of government, that federalism is highly conducive to regional autonomy arrangements, and that UN intervention plays a pivotal role in arranging power sharing institutions between government and rebel groups in the transition from civil war to peace. These finding imply that the UN and other international actors should seriously consider the institutional context of civil-war torn countries when they intervene in and propose a power sharing deal during peace negotiations, because an incompatible set of institutions is far more difficult to be arranged and would not function as effectively as designed.

Political institutions often change as a consequence of resolving civil war. Especially when a civil war ends through peace negotiations, institutional (re-) arrangement is one of the core issues at the negotiating table. In ending violent civil conflicts, what type of political institutions has been arranged and why? While no systematic and comprehensive answer has been offered by the academic community, competing policy prescriptions based on a functionalist logic—a particular type of institutions

To systematically explore these questions, I review the intellectual debates on consociationalism and the power sharing approach to conflict management and formulate three testable hypotheses: an institutional affinity hypothesis, a United Nations (UN) intervention effect hypothesis, and a conflict characteristics hypothesis. These three hypotheses are empirically tested by cross-national data on thirty-six cases of negotiated settlements in the postCold War period. The empirical results of this study suggest that only a certain type of preexisting constitutional rule has institutional affinity with a particular component of power sharing and UN intervention plays an active role in arranging power sharing institutions during peace negotiations. From this I draw some policy implications and call for a more in-depth study about the relationship between political institutions and conflict resolution to develop an actor-centered theory of institutional arrangements.

Ⅱ. Political Institutions and Civil War Resolution

The Political Instability Task Force (PITF) put forward a bold claim: “It’s the Institutions, Stupid!” The Task Force predicted that countries with anocratic political institutions had eight to twenty-nine times higher probabilities of civil conflicts than countries that were fully autocratic or fully democratic, implying that anocratic institutions should be avoided to reduce the chances for large-scale political violence.1) The PITF’s efforts to forecast the impact of institutions on the risk of violent conflict is provocative, but the concept of anocracies, placed in the middle between autocracies and democracies, entails an overly broad range of institutional components. It is thus difficult to pinpoint which institutional aspects of anocracies actually raise the odds of near-term political crises and what particular institutions ought to be adopted to reduce the extremely high risk of conflict.2)

In this regard, the theory of consociationalism sheds more light on what institutions are especially helpful to ensure political stability in deeply divided societies. This theory posits that certain political institutions perform better than others in promoting a positive sum perception of political interactions and encouraging cooperation of various linguistic, religious, or ethnic communities living within the same boundary of sovereign states. Such consociational institutions include a grand coalition among political leaders of all significant segments of society, a proportional representation (PR) of major groups in elected office, a mutual veto between majority and minority groups in government decision making, and segmental autonomy granted under federalism.3) Consociationalism was originally developed to explain democratic stability in pluralistic Western European societies such as Austria, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Switzerland.4) But its scope has been widened to cover deeply divided societies in other parts of the world as well.5)

However, critics of consociationalism have raised serious doubts about its core assumption and claims. One conceptual critique is that consociational theory blurs the distinction between a normative and an empirical typology of democracy: in ideal types of democratic regimes, the opposite of consociational democracy is a majoritarian democracy, whereas in Lijphart’s fourfold empirical typology6) the opposite of consociational democracy is a centrifugal democracy.7) As the former typology (consociational versus majoritarian) is primarily based on institutional terms while the latter is based on behavioral ones, this discrepancy between normative and empirical types of democratic regimes causes problems in classifying political regimes in empirical research.

A more articulated and influential critique is that consociational theory assumes intra-group homogeneity under strong leadership. As this assumption is conceived as a precondition for the promotion of elite cooperation among different ethnic or religious groups, consociationalism pays little attention to managing within-group competition. This unmanaged centrifugal competition in turn imposes enormous constraints on democratic collaboration among rival groups.8) Furthermore, consociational institutions are in fact likely to serve to reinforce preexisting ethnic, religious, and linguistic cleavages. Party leaders under the incentive structure provided by PR systems have less motivation to appeal for voter support outside of their own constituencies than those under alternative electoral systems. Federalism can also lock preexisting cleavages into the boundaries of subnational units. The empirical works in this line of thought show that consociational arrangements are less likely to deter the escalation of ethnic conflicts to ethnonational crises in ethnically divided societies;9) proportional electoral systems do not produce inclusive governments;10) ethno-federalism in postcommunist states neither maintains peace nor fosters democracy.11)

These debates on the functional aspect of consociationalism directly shape intellectual discussions on what type of political institutions should be arranged in countries emerging from civil wars. Proponents of consociationalism claim that its core argument can be directly applied to civil war resolution and post-conflict peacebuilding and suggest power sharing among warring parties in governmental institutions.12) The logic behind this power sharing approach is that allocating executive and electoral seats to civil war adversaries can reduce the security dilemma and the credible commitment problem, which are two fundamental barriers to negotiated settlements of civil wars; granting significant autonomy to secessionist rebels can stop the fighting as quickly as possible, as it directly addresses the root cause of rebellion. These power sharing institutions are also expected to reduce fear and encourage cooperative behavior of former warring parties by ensuring that they will be closely involved in government decision making.

Therefore, the proponents have contended that power sharing is particularly useful when civil war adversaries have reached a mutually destructive stalemate. It can provide an institutionalized security guarantee and a strong incentive for warring parties to initiate negotiations, sign a bargain for peace, and implement peace settlement terms. Seemingly indivisible stakes become divisible, to some extent, by balancing the distribution of political power among the settlement parties. In this vein, Walter’s findings are suggestive.13) She demonstrated that government and rebels are 38% more likely to sign a peace treaty if it includes a political power sharing provision; they are 40% more likely if it includes a territorial autonomy arrangement.

However, the power sharing approach has been criticized for the same conceptual problem as consociational theory. Bogaards particularly points out that power sharing is a clear-cut case of conceptual stretching, in that the term only adopts the political characteristics of consociationalism in order to expand drastically the domain of empirical application.14) While consociationalism was proposed for particular types of societies (i.e., ethnically or religiously plural ones), power sharing is now suggested as the only viable institutional option for all kinds of divided societies. This conceptual stretching causes unnecessary ambiguities in defining and operationalizing power sharing. Although Lijphart has used power sharing and consociationalism as synonymous,15) power sharing is often considered to describe purely ad hoc political concessions between government and rebels in civil war countries16) or, conversely, a whole range of political institutions intended to reduce tension and encourage cooperation among rival ethnic groups.17) This definitional ambiguity in turn leads to very different operationalization of power sharing: while Norris focuses only on formal institutions such as PR and federalism,18) Hartzell and Hoddie operationalize power sharing more comprehensively, including political, economic, military, and territorial aspects of peace agreements in ending civil wars.19)

In addition to this conceptual issue, the power sharing approach is criticized as a short-term solution to end civil war via peace negotiations.20) It tends to build wartime cleavages into post-war political structures, thereby providing a strong incentive structure for former warring parties to maintain the status quo of the initial institutional set-up and perpetuate the war-induced cleavages into post-war politics. That is, power sharing arrangements provide a political opportunity structure for the leaders of former warring groups to frame all of their demands as constitutional rights, leading to the proliferation of institutional weapons that can be used against a newly established central government. Another fundamental problem of power sharing is its institutional rigidity. Once a power sharing system is arranged, it is hard to change the initial institutional set-up. The end result is often either the collapse of the power sharing system and the return to conflict, or the persistence of ineffective and weak central governmental institutions.

Along with the pros and cons of the power sharing approach, the extant literature that has empirically investigated the effects of power sharing on post-conflict peace has provided mixed results. Whereas Hartzell and Hoddie found that power sharing arrangements make the recurrence of civil war less likely,21) Mukherjee discovered that power sharing agreements among civil war adversaries contribute to lasting peace after some civil wars but not others, depending on whether the agreements reflect accurate information about the combatants’ military capacities and resolution to end the fighting.22) Even when Hoddie and Hartzell decompose their comprehensive measure of power sharing,23) political power sharing turns out to be insignificant in improving the chances for establishing durable peace; the significant components are only territorial and military power sharing. Yet Glassmyer and Sambanis’s analysis presents another contradictory result: military power sharing agreements specifying how rebel-military integration will proceed do not provide an effective peacebuilding mechanism in civil war countries.24)

However, these intellectual debates do not engage directly with the question of under what conditions a particular type of power sharing arrangements is adopted. They offer only some hints. First, consociational theory implies that a particular type of preexisting constitutional arrangements is conducive to the adoption of a power sharing agreement between government and rebel groups when they reach a military stalemate and negotiate how the conflict should be resolved. I call this speculation an institutional affinity hypothesis. Put specifically, a parliamentary form of government would be a better institutional environment for the adoption of executive-level power sharing because it is “a system of mutual dependence” that avoids the winner-take-all outcome of presidential elections.25) By the same token, a mixed form of government (or semi-presidentialism) can be considered more compatible with executive power sharing than presidential systems because equally powerful presidency and parliament can reduce fears of the domination of one group over the other and promote the formation of a broad coalition government.26) In line with this reasoning, if the preexisting electoral rule is proportional representation regardless of whether or not elections had taken place as stipulated in constitutions, it would be relatively easier for warring parties to agree on an electoral quota system that can guarantee the legislative power of minority groups. Also, federalism is a better constitutional environment than unitary systems for regional autonomy arrangements during a negotiated end to civil war because the preexisting constitutional order need not be amended to delegate rule-making power from the national-level government to subnational units.

Second, proponents of the power sharing approach have also emphasized a positive role of the UN in adopting power sharing institutions in post-civil war transitions. For instance, Walter shows that UN intervention along with power sharing arrangements increases substantially the chances for resolving a civil war through peace negotiations.27) Wantchekon also offers a theoretical logic about the role of an impartial external mediator in arranging and implementing a power sharing deal as civil war adversaries cannot resolve the conflict by themselves.28) Lijphart thus made a strong policy proposal that the international community should be aware that power sharing is the only feasible institutional option for peaceful resolution of civil conflicts.29) As all these arguments expect, and even encourage, the effects of UN intervention on power sharing institutional arrangements, I call them a UN intervention effect hypothesis.

Third, despite the pitfalls pointed out by opponents, power sharing can be conceived as an inevitable compromise in cases where deadly violence would have not ended without such a short-term institutional arrangement. That is, power sharing may be the only solution to stop the bloodshed in most difficult cases of civil war resolution. It is then plausible to expect that power sharing institutions are more likely to be adopted in ethnic or religious civil wars than in ideological ones because identity-based conflicts pose more significant impediments to peaceful resolution of conflict. In the same vein, power sharing is more likely to be arranged in long-standing conflicts that have not been resolved by other methods of conflict resolution and in more costly cases in terms of the number of casualties. As this line of reasoning implies that power sharing arrangements are endogenous to war-related factors, I call it a conflict characteristics hypothesis.

1)Jack A. Goldstone and Jay Ulfelder, “How to Construct Stable Democracies,” Washington Quarterly 28-1 (Winter 2004-05), pp. 9-20. 2)The PITF’s forecasting model suggests that nominal democracies with factionalized political competition are the most vulnerable to violent conflicts; autocracies with some political competition are the second. Yet factionalized political competition is less indicative of institutional elements of a political system than of the patterns of political behavior, since its main characteristics are identified as parochialism or polarization of major political parties and mobilization of violent collective action (Ibid., pp. 15-16). 3)Arend Lijphart, Democracy in Plural Societies: A Comparative Explanation (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1977), pp. 25-52. 4)Hans Daalder, “The Consociational Democracy Theme,” World Politics 26-4 (1974), pp. 604-621; Arend Lijphart, The Politics of Accommodation: Pluralism and Democracy in the Netherlands (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1968). 5)Arend Lijphart, 1977, op. cit., pp. 142-176; Wolf Linder and André Bächtiger, “What Drives Democratization in Asia and Africa?” European Journal of Political Research 44-6 (2005), pp. 861-880; Eric A. Nordlinger, Conflict Regulation in Divided Societies (Cambridge: Center for International Affairs, Harvard University, 1972). 6)Lijphart classifies democratic regimes along two dimensions as follows (Arend Lijphart, 1977, op. cit., p. 106): 7)Matthijs Bogaards, “The Uneasy Relationship between Empirical and Normative Types in Consociational Theory,” Journal of Theoretical Politics 12-4 (2000), pp. 295-423. 8)Donald Horowitz, Ethnic Groups in Conflict (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1985); Donald Horowitz, “Constitutional Design: Proposals versus Processes,” in Andrew Reynolds (ed.), The Architecture of Democracy: Constitutional Design, Conflict Management, and Democracy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), pp. 15-36; Stephen John Stedman, “Spoiler Problems in Peace Processes,” International Security 22-2 (1997), pp. 5-53. 9)Philip Roeder, “Power Dividing as an Alternative to Ethnic Power Sharing,” in Philip Roeder and Donald Rothchild (eds.), Sustainable Peace: Power and Democracy after Civil Wars (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005), pp. 51-82. 10)Benjamin Reilly, Democracy in Divided Societies: Electoral Engineering for Conflict Management (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001). 11)Valerie Bunce and Stephen Watts, “Managing Diversity and Sustaining Democracy: Ethnofederal versus Unitary States in the Postsocialist World,” in Philip Roeder and Donald Rothchild (eds.), Sustainable Peace: Power and Democracy after Civil Wars (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005), pp. 133-158. 12)David Lake and Donald Rothchild, “Containing Fear: The Origins and Management of Ethnic Conflict,” International Security 21-2 (1996), pp. 41-75; Arend Lijphart, “The Wave of Power-Sharing Democracy,” in Andrew Reynolds (ed.), The Architecture of Democracy: Constitutional Design, Conflict Management, and Democracy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), pp. 37-54; Ian O’Flynn and David Russell (eds.), Power Sharing: New Challenges for Divided Societies (London: Pluto, 2005); Donald Rothchild, “Settlement Terms and Postagreement Stability,” in Stephen John Stedman, Donald Rothchild, and Elizabeth Cousens (eds.), Ending Civil Wars: The Implementation of Peace Agreements (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2002), pp. 117-138; Timothy Sisk, Power Sharing and International Mediation in Ethnic Conflicts (Washington D.C.: US Institute of Peace, 1996). 13)Barbara F. Walter, Committing to Peace: The Successful Settlement of Civil Wars (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002), pp. 77-83. 14)Matthijs Bogaards, op. cit., pp. 415-417. 15)For comparison see Arend Lijphart, Power-Sharing in South Africa (Berkeley, CA: Institute of International Studies, 1985); Arend Lijphart, “The Power-Sharing Approach,” in Joseph V. Montville (ed.), Conflict and Peacemaking in Multiethnic Societies (Toronto: Lexington, 1990), pp. 491-509; Arend Lijphart, 2002, op. cit.; Arend Lijphart, “Constitutional Design for Divided Societies,” Journal of Democracy 15-2 (2004), pp. 96-109. 16)See for example, René Lemarchand, “Consociationalism and Power Sharing in Africa: Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of Congo,” African Affairs 106-422 (2006), pp. 1-20. 17)For instance, Sisk conceives power sharing as consisting of both Lijphart’s consociational approach and Horowitz’s integrative approach to conflict regulation (Timothy Sisk, op. cit.). 18)Pippa Norris, Driving Democracy: Do Power-Sharing Institutions Work? (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008). 19)Hartzell and Hoddie define political power sharing as electoral, administrative, or executive proportional representation between government and rebels, economic power sharing as proportional distribution of economic resources, military power sharing as a balanced distribution of the state’s coercive power (i.e., military and police) among the former adversaries of civil war, and territorial power sharing as a division of autonomy among different levels of government on the basis of federalism or regional autonomy arrangements (see Caroline Hartzell and Matthew Hoddie, “Institutionalizing Peace: Power Sharing and Post-Civil War Conflict Management,” American Journal of Political Science 47-2 [2003], p. 320). As each component of power sharing is added to a five-point measure of a comprehensive power sharing index, all thirty-eight negotiated settlements of civil wars in Hartzell and Hoddie’s data include at least one dimension of power sharing, except one case: the Angolan peace agreement that ended temporarily the insurgency of the União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola (the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola, UNITA) in 1989. 20)For example, see Anna K. Jarstad and Timothy D. Sisk (eds.), From War to Democracy: Dilemmas of Peacebuilding (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008); Jai Kwan Jung, “Power-Sharing and Democracy Promotion in Post-Civil War Peace-building,” Democratization 19-3 (2012), pp. 486-506; Jai Kwan Jung, “The Paradox of Power Sharing,” Korean Political Science Review 46-6 (2012), pp. 59-84; Donald Rothchild and Philip Roeder, “Power Sharing as an Impediment to Peace and Democracy,” in Philip Roeder and Donald Rothchild (eds.), Sustainable Peace: Power and Democracy after Civil Wars (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005), pp. 29-50. 21)Caroline Hartzell and Matthew Hoddie, op. cit. 22)He identifies power sharing if peace agreements include any of the following political provisions: 1) appointment of rebel leaders to cabinet positions; 2) appointment of rebels to civil service, foreign service, and commissions; 3) use of a PR electoral system (Bumba Mukherjee, “Why Political Power-Sharing Agreements Lead to Enduring Peaceful Resolution of Some Civil Wars, But Not Others?” International Studies Quarterly 50-2 [2006], pp. 479-504). Since his measure of power sharing is identical to Hartzell and Hoddie’s political dimension of power sharing, the correlation between the two measures is 0.93. 23)Matthew Hoddie and Caroline Hartzell, “Power Sharing in Peace Settlements: Initiating the Transition from Civil War,” in Philip Roeder and Donald Rothchild (eds.), Sustainable Peace: Power and Democracy after Civil Wars (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005), pp. 83-106. 24)Katherine Glassmyer and Nicholas Sambanis, “Rebel-Military Integration and Civil War Termination?” Journal of Peace Research 45- 3 (2008), pp. 365-384. 25)Alfred Stepan and Cindy Skach, “Presidentialism and Parliamentarism in Comparative Perspective,” in Juan J. Linz and Arturo Valenzuela (eds.), The Failure of Presidential Democracy (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994), p. 120. 26)See for example, Barbara Geddes, “Initiation of New Democratic Institutions in Eastern Europe and Latin America,” in Arend Lijphart and Carlos H. Waisman (eds.), Institutional Design in New Democracies: Eastern Europe and Latin America (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996), pp. 15-41; Linda Kirschke, “Semipresidentialism and the Perils of Power Sharing,” Comparative Political Studies 40-11 (2007), pp. 1372-1394; Arend Lijphart, “Democratization and Constitutional Choices in Czecho-Slovakia, Hungary and Poland 1989-91,” Journal of Theoretical Politics 4-2 (1992), pp. 207-223; Matthew Soberg Shugart, “The Inverse Relationship between Party Strength and Executive Strength: A Theory of Politicians’ Constitutional Choices,” British Journal of Political Science 28-1 (1998), pp. 1-29. 27)Barbara Walter, op. cit. 28)Leonard Wantchekon, “The Paradox of ‘Warlord’ Democracy: A Theoretical Investigation,” American Political Science Review 98-1 (2004), pp. 17-33. 29)Arend Lijphart, 2004, op. cit.

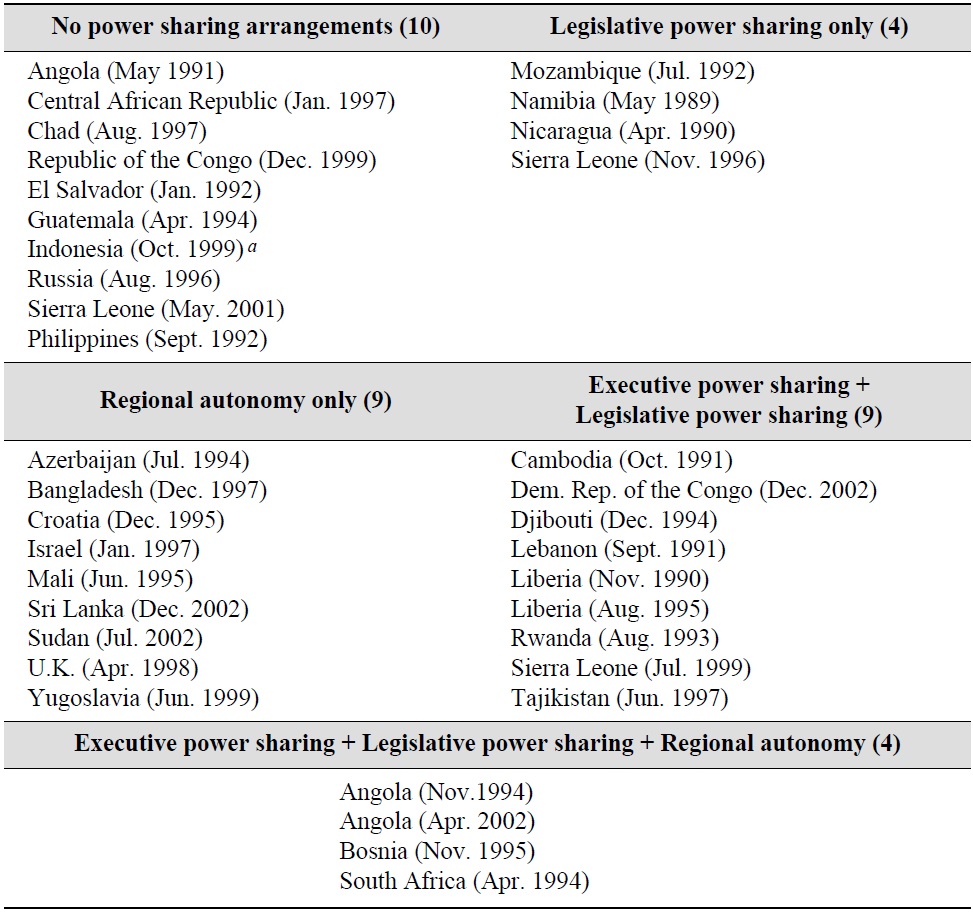

To test the three sets of hypotheses drawn from the debates on consociationalism and the power sharing approach to civil war resolution and peacebuilding, I created three dependent variables and three sets of independent variables with thirty-six cases of negotiated settlements in the post-Cold War period. Between 1989 and 2002, a total of sixty-nine civil wars ended. Thirty-six of the sixty-nine cases were resolved the conflict through signing a peace agreement. In classifying civil war termination into one-sided military victory versus negotiated settlements, I used Sambanis’s civil war data that provide information on the month of civil war termination.30) In his classification, negotiated settlements refer to cases where a peace treaty produced at least six months of peace, while one-sided victory means that the armed fighting stopped with a clear winner at least for six months.

The dependent variables are three components of power sharing arrangements that are designed to end a civil war: executive power sharing (sharing presidency and cabinet positions among warring parties), legislative power sharing (proportional allocation of electoral seats via a quota system), and regional autonomy arrangement between government and territorially concentrated rebel groups. This coding scheme is based on Lijphart’s clarification on the notion of power sharing. Of the four consociational institutions originally formulated in

In contrast, the other three elements of power sharing institutional arrangements are clearly observable. Executive power sharing is coded as 1 if a peace agreement includes any provision regarding how the chief executive and ministerial positions would be distributed to warring parties 34); legislative power sharing is coded as 1 if parliamentary seats are agreed to allocate to the adversaries of civil war through adopting a fixed quota system or a PR system; regional autonomy is coded as 1 if a peace agreement stipulates the devolution of power to territorially concentrated insurgent groups or a particular segment of the population. Each component of power sharing institutions was created by reading the text of peace agreements. Principal data sources include the Peace Agreement Digital Collection in the US Institute of Peace,

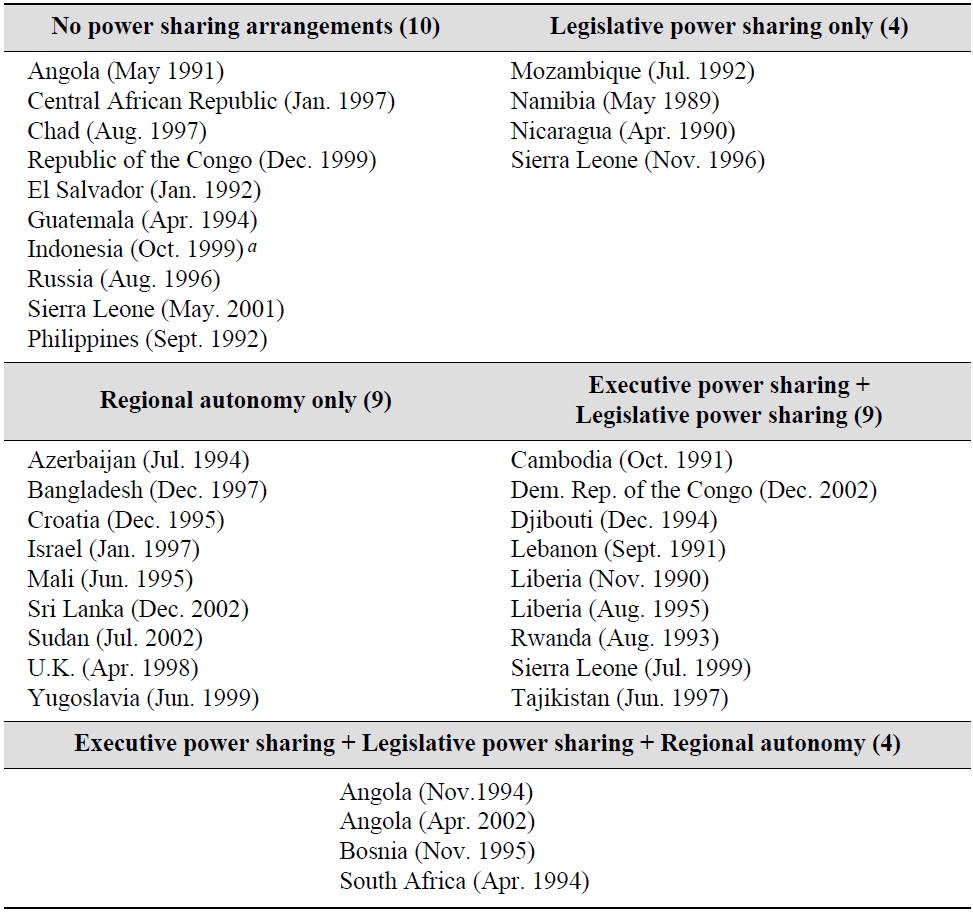

[Table 1.] Power Sharing Arrangements in Negotiated Settlements of Civil Wars

Power Sharing Arrangements in Negotiated Settlements of Civil Wars

It is worth noting in Table 1 that power sharing arrangements occur only in negotiated settlement cases because if a civil war ends in a decisive victory either by government or by rebels the winner has little reason to share power with the loser,35) but negotiated settlements do not always arrange power sharing institutions. In ten out of the thirty-six negotiated settlement cases, the fighting stopped through a mere bilateral ceasefire agreement or through a peace treaty simply providing that rebel groups would be allowed to enter into political competition as legal political parties. The remaining twenty-six cases show that at least one institutional component of power sharing was adopted as a result of peace negotiations.

Why a particular component of power sharing was adopted in some cases but not in others? To answer this question, I constructed three sets of independent variables. First, preexisting constitutional rules are measured by the type of government, electoral systems, and federalism to assess institutional affinity with a certain component of power sharing. For the type of government, I employ Cheibub’s criteria for classifying executivelegislative relations into parliamentary, mixed, and presidential systems. His classification rule is based on three questions: 1) Is the government responsible to the elected assembly?; 2) Is there an independently elected president?; and 3) Is the government responsible to the president?36) Unlike other classifications such as the World Bank political institutions data and Gerring

Evaluating institutional affinity between a certain constitutional arrangement and a particular type of power sharing runs a risk of endogeneity problems if the conceptual distinction between the two sets of institutions is not clear or if temporal sequence is confused. For instance, PR electoral systems and federalism that were already stipulated in constitution or in practice before the end of civil war can be confused with legislative power sharing and regional autonomy that were arranged during peace negotiations. To solve this problem is one of the reasons why the actual text of peace agreements is employed in coding each component power sharing. That is, if a PR system, for example, had already been in practice and was not an issue in peace negotiations, as in El Salvador when the war with the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) ended in a negotiated settlement in 1992, I do not regard it as a legislative power sharing arrangement.

Second, the variable of UN intervention is constructed to test the UN intervention effect hypothesis by collecting information on whether the UN mediated peace negotiations to resolve the conflict. Using Doyle and Sambanis’s dataset and various documents on the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) website,39) it is coded as 1 if UN mediators were present during peace processes, 0 otherwise.

The third set of independent variables is war-related factors that are likely to lead to the adoption of a particular element of power sharing in stopping the armed fighting. Using Doyle and Sambanis’s dataset, the type of war classifies civil wars into ethnic or religious conflicts (coded as 1) versus ideological ones40); the duration of war measures how long the conflict lasted from the onset to the end via peace negotiations41); and, lastly, the costs of war are measured by the number of people killed and displaced during a civil war.42)

30)Nicholas Sambanis, “What Is Civil War? Conceptual and Empirical Complexities of an Operational Definition,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 48-6 (2004), pp. 814-858. 31)Arend Lijphart, 2004, op. cit. 32)The Dayton Peace Agreement is an exception in that it has constitutionally guaranteed the veto power of each ethnic group in Bosnia-Herzegovina. 33)It required that parliamentary seats be equally distributed to the Conservative and the Liberal parties and that all legislation be passed by a two-thirds majority. 34)Typical examples of executive power sharing are the interim constitution in South Africa that granted all parties with a minimum of five percent of the legislative seats the right to be represented in the cabinet, the San Carlos agreement in Columbia that stipulated the equal representation of the Conservative and the Liberal parties in the cabinet and alternation between the two parties in the presidency, and the 1943 National Pact and 1989 Ta’if Accord in Lebanon that gave the presidency to the Maronites and the premiership to the Sunnis. 35)Indeed, there have been few power sharing experiments when a civil war ended by onesided military victory. The only case of power sharing after ending a civil war by military victory is Burundi’s power sharing experiment in 1993-96. 36)José Antonio Cheibub, Presidentialism, Parliamentarism, and Democracy (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 33-42. 37)John Gerring, Strom C. Thacker, and Carola Moreno, “Centripetal Democratic Governance: A Theory and Global Inquiry,” American Political Science Review 99-4 (2005), pp. 549-566. 38)Matt Golder, “Democratic Electoral Systems around the World, 1946-2000,” Electoral Studies 24-1 (2005), pp. 103-121. 39)Michael Doyle and Nicholas Sambanis, Making War and Building Peace: United Nations Peace Operations (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006); For the UN DPKO documents, go to

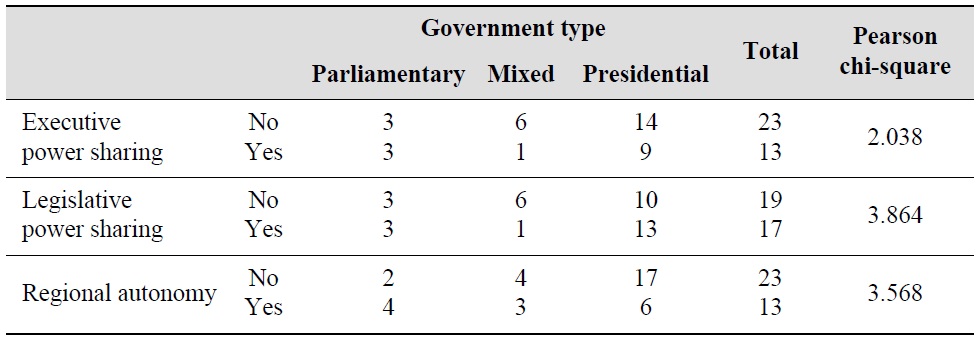

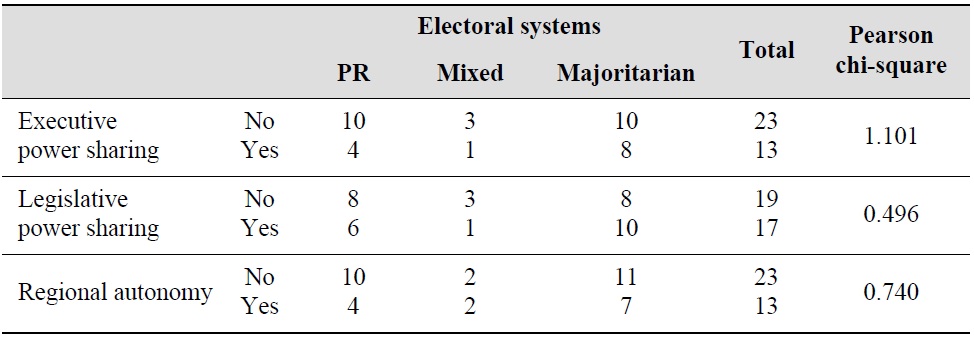

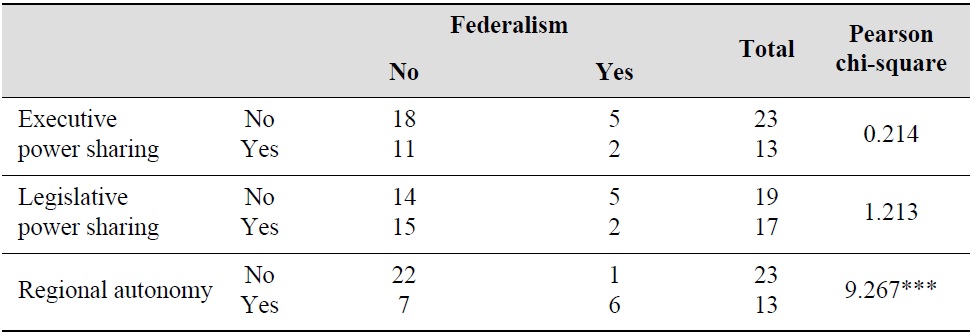

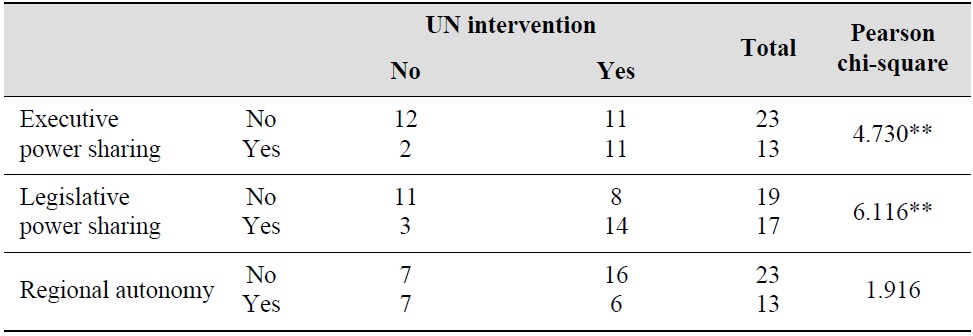

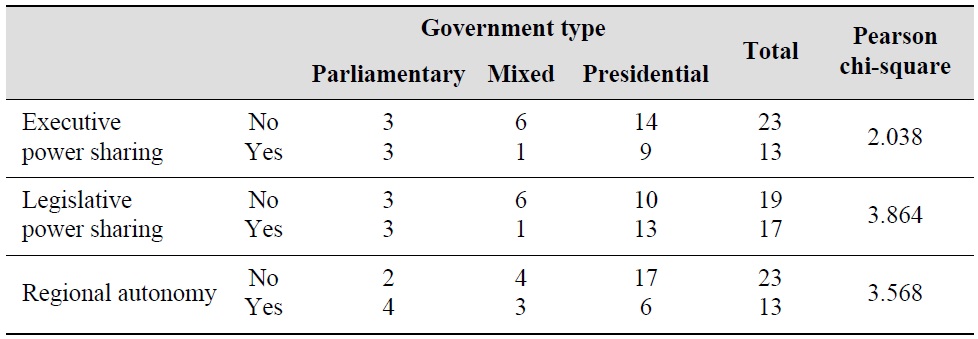

To examine institutional affinity between preexisting constitutional rules and power sharing arrangements, Tables 2 to 4 present the distribution of thirty-six negotiated settlement cases by the type of government, electoral systems, and federalism, respectively. In these tables, we can first see that executive power sharing was adopted in thirteen cases, legislative power sharing in seventeen cases, and regional autonomy arrangement in thirteen cases.

[Table 2.] Distribution of Power Sharing Arrangements by the Type of Government

Distribution of Power Sharing Arrangements by the Type of Government

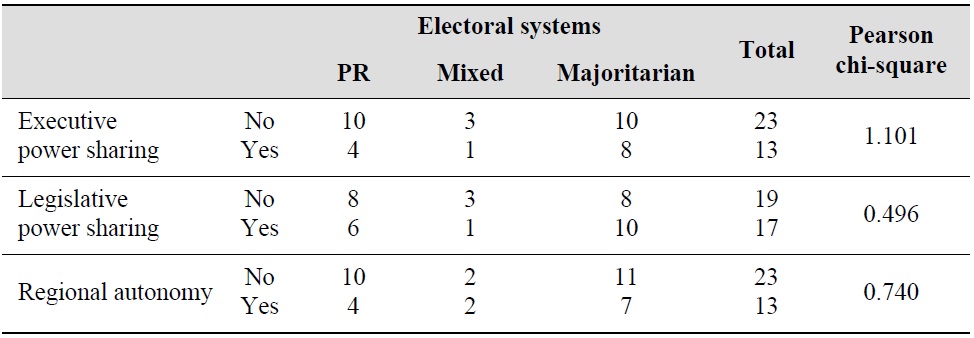

[Table 3.] Distribution of Power Sharing Arrangements by the Type of Electoral Systems

Distribution of Power Sharing Arrangements by the Type of Electoral Systems

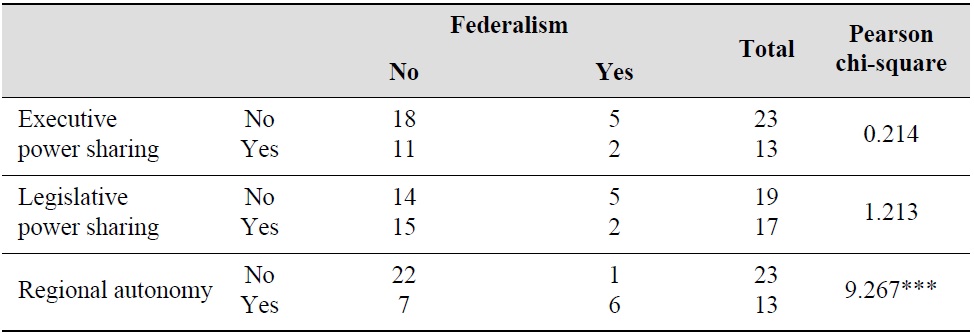

[Table 4.] Distribution of Power Sharing Arrangements by Federalism

Distribution of Power Sharing Arrangements by Federalism

Table 2 shows that a presidential form of government is stipulated in constitutions of twenty-three negotiated settlement cases, parliamentary regimes in six cases, and mixed systems in seven cases. Although each component of power sharing was adopted more frequently under presidential systems, no clear pattern can be found in the relationship between government type and power sharing arrangements, given the nonsignificant chi-square test statistics.

With regard to institutional affinity between electoral systems and power sharing arrangements, Table 3 shows that PR electoral systems were constitutionally provided in fourteen cases of civil war countries that ended the conflict through peace negotiations, majoritarian systems in eighteen cases, and mixed electoral systems in four cases. Power sharing institutions were adopted more frequently under majoritarian electoral systems, but, again, none of the chi-square test statistics is significant.

In Table 4, we can see that twenty-nine cases of peace agreements during the post-Cold War period occurred under unitary systems and seven cases under federalism. Executive and legislative power sharing appear to be adopted more frequently under unitary systems, but they are not statistically significant relationships. Only the relationship between federalism and regional autonomy arrangement produces a significant chi-square test result. It substantively means that granting regional autonomy to secessionist insurgents is easier in countries where federalism was already in practice than in countries under unitary systems.43)

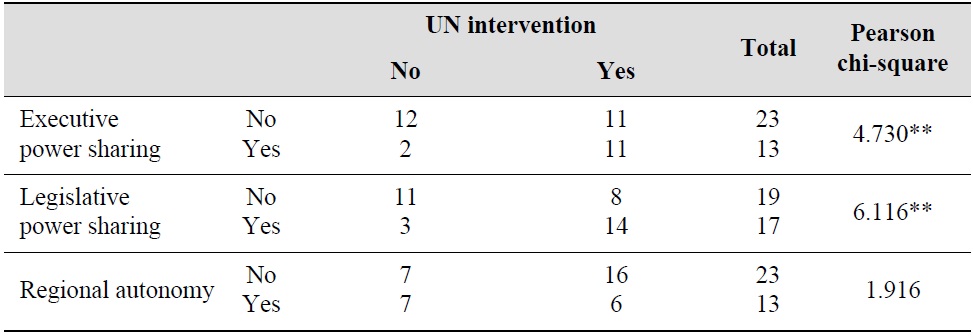

The institutional affinity hypothesis posits that under certain preexisting constitutional rules, a particular component of power sharing is relatively easy to agree upon among warring parties. Yet it is not well supported by cross-tabulation results in Tables 2 to 4, except for the significant affinity between federalism and regional autonomy arrangement. Then what about the role of UN intervention in peace processes? Table 5 presents that UN mediated peace negotiations in twenty-two cases. One can find a clear pattern in Table 5 that executive and legislative power sharing was adopted when UN mediators were present at the peace negotiation table. These statistically significant relations of UN intervention with executive and legislative power sharing imply that the UN as a neural mediator has preferred to resolve civil conflicts by relying on the power sharing approach, even if it is a short-term solution as the critics of the power sharing approach have contended.

[Table 5.] Distribution of Power Sharing Arrangements by UN Intervention

Distribution of Power Sharing Arrangements by UN Intervention

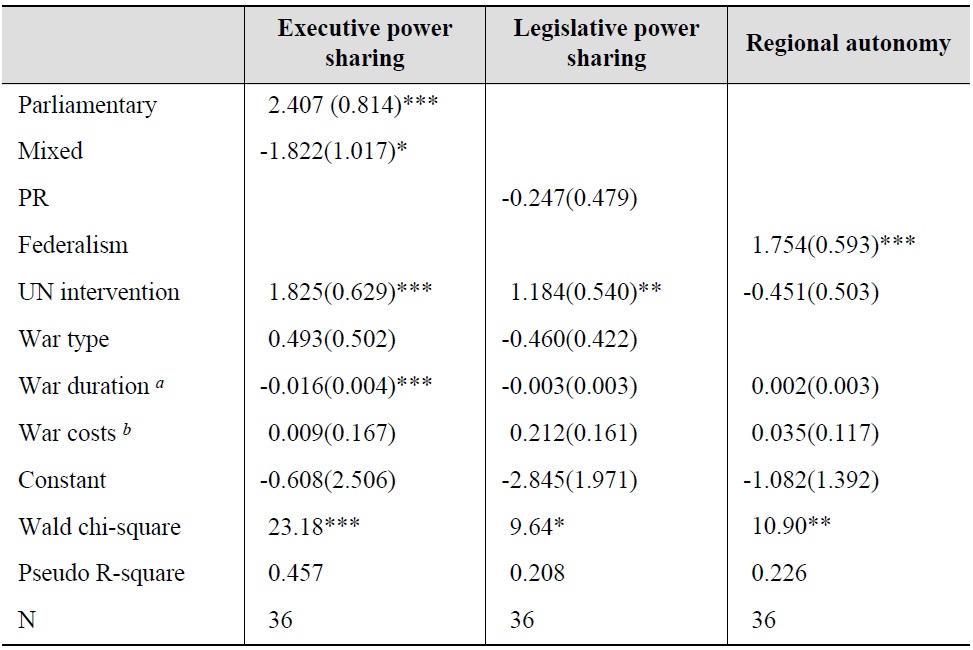

Yet the cross-tabulation results in Tables 2 to 5 are not conclusive. I thus conduct a multivariate analysis of under what conditions power sharing institutions are more likely to be adopted in the negotiated end to civil war. Table 6 presents the results of the probit analysis. Here, the dependent variables are three components of power sharing, and independent variables are included as hypothesized in the previous sections. Since some countries (Angola, Liberia, and Sierra Leone) experienced multiple numbers of civil war resolution during the post-Cold War period, I clustered all thirty-six observations and estimated robust standard errors to control for withincountry correlations.

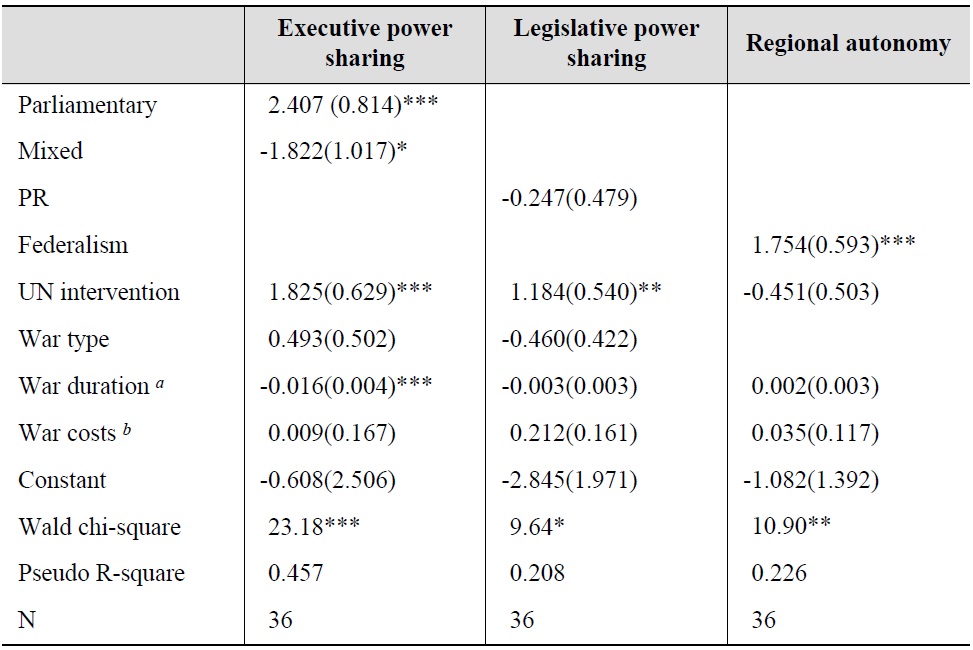

[Table 6.] Probit Analysis of the Adoption of Power Sharing Arrangements

Probit Analysis of the Adoption of Power Sharing Arrangements

To examine the conditions under which executive power sharing is more likely to be adopted, the type of government is included along with UN intervention and the three war-related factors: War type, War duration, and War costs. Setting presidential systems to be the reference category, the executive power sharing model in Table 6 shows that parliamentary systems are more conducive to the sharing of presidential power and ministerial positions. Put more precisely, a parliamentary form of government increases the predicted probability of adopting executive power sharing by 32%, compared to presidential systems.44) This estimation result supports the institutional affinity hypothesis drawn from the consociational logic of emphasizing the consensual nature of parliamentarism in contrast to the winner-take-all nature of presidentialism.45) Yet, as opposed to consociational theory, executive power sharing is less likely to be adopted under a semipresidential form of government than under presidentialism. The estimation results in the legislative power sharing model also indicate that PR electoral system is not a better constitutional environment for the arrangement of sharing legislative power through a fixed quota system. However, granting regional autonomy to territorially concentrated rebels is relatively easier under federalism than under unitary systems, as consociationalism implies.46) Overall, the multivariate analysis in Table 6 provides only mixed empirical evidence for the institutional affinity hypothesis. The only statistically significant findings that are also substantively consistent to the consociational logic of political institutions are that parliamentarism is a better institutional environment for the adoption of executive power sharing than the alternative types of government and that federalism is highly conducive to regional autonomy arrangements.

In comparison, UN intervention in peace negotiations significantly increases the likelihood of adopting executive and legislative power sharing. With holding all the other variables to their mean or median values, the predicted probabilities of executive and legislative power sharing arrangements increase from 11.5% to 45.9% and from 21.7% to 61.4%, respectively, if the UN intervenes in negotiated settlements of civil wars. These substantial effects of UN intervention do not mean that the mere presence of UN mediators leads to the power sharing arrangements. The empirical results reflect the fact that when the UN intervened in peace processes in civil war-torn countries, it has actively pursued the power sharing approach to stop the bloodshed as quickly as possible. This interpretation can be supported by a number of anecdotal evidence that the UN has strongly suggested or even imposed a power sharing deal on civil war adversaries since its successful experience in ending Namibia’s long-standing conflict with a power sharing arrangement.47)

The estimation results for the type, duration, and costs of civil war fare poorly for the functionalist logic that expects power sharing institutions to be arranged in most difficult cases of civil war resolution.48) The three warrelated factors do not account for the adoption of executive and legislative power sharing and regional autonomy arrangement. The only significant coefficient estimate is for the duration of war, but the direction is opposite to the expectation drawn from the power sharing approach.49)

43)Those cases in which regional autonomy was granted as a result of a peace agreement under preexisting federalism are Azerbaijan, Bosnia-Herzegovina, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Sudan, and Yugoslavia. The correlation between federalism and regional autonomy arrangement is also 0.507 (significant at 99%). 44)This predicted probability is computed by estimating the change in marginal probabilities of adopting executive power sharing from nonparliamentary to parliamentary systems, holding all the other variables to their mean or median values. The estimated change is from 57.2% to 89.4%. 45)It makes more substantive sense if we look at the cases in which executive power sharing was arranged in peace process under parliamentarism: Cambodia in 1991, Lebanon in 1991, and South Africa in 1994. If the type of government were a presidential system in these cases, it would have been almost impossible for the warring parties to agree on sharing executive power. 46)While holding all the other variables to their mean or median values, a preexisting federal system raises the predicted probability of regional autonomy arrangements by over 60%. 47)The power sharing approach requires a high degree of commitment by the UN as it is necessary to monitor and implement a power sharing deal. 48)The type of civil war variable cannot be included in the regional autonomy model since regional autonomy arrangements occurred only in resolving ethnic or religious conflicts. 49)These estimation results do not change substantively even if additional variables, such as GDP per capita, are added in the models.

Drawing on the intellectual debates on consociational theory and the power sharing approach, this article has investigated the types of political institutions arranged in the transition from civil war to peace and the conditions under which a particular type of institution is likely to be adopted. The empirical results showed that only a certain type of preexisting constitutional rule has institutional affinity with a particular component of power sharing and the UN has played an active role in arranging power sharing institutions during peace negotiations. A clear policy implication from this finding is that the UN should seriously consider the institutional context of civil-war torn countries when it intervenes in peace process. An incompatible set of institutions is far more difficult to be arranged and would not function as effectively as designed.

Yet, while highlighting the role of UN intervention, this article has paid little attention to the role of domestic actors in the transition from civil war to peace. The UN mediators often pushed warring parties into a power sharing deal when they intervened in peace processes, but not all of their forceful proposals were accepted by leaders of warring parties, as seen in the Mozambican government’s rejection of a power sharing proposal when the country’s civil war was resolved by a UN-mediated peace process. Put differently, it is natural to expect that external mediators and domestic actors have distinctive institutional preferences in resolving civil war through peace negotiations. Domestic actors’ preferences are likely to be shaped by the balance of power between government and rebel forces and the type of institutions that had existed before the outbreak of civil war. But external actors like the UN prefer to arrange political institutions that are believed to be efficient for prompt resolution of conflicts. Then the type of institutions finally arranged will be determined by the degree of convergence between distinctive actors’ preferences. This actor-centered logic of institutional adoption calls for a more in-depth study about the relationship between political institutions and conflict resolution.