Since the mid-1990s, the world has witnessed an unprecedented outburst of free trade agreements (FTAs). Although economic regionalism has long been an important feature of the international political economy, recent developments outweigh the previous “waves” in its pervasiveness.1) The World Trade Organization (WTO) reports that almost 300 additional preferential trade agreements (PTAs) have been notified to the WTO since its inception in 1973 and that virtually every member country is now a party to at least one PTA.2)

This new phenomenon has called upon scholarly attention as to the determinants of the spread of economic regionalism. Economists, equipped with the Vinerian terms of trade effect,3) have attributed the uprising of FTAs to the expected welfare gains and the concomitant domino effects.4) Political scientists have identified both international and domestic political factors that have led to this new development. Internationally, the changes in global power distribution and the multilateral trade regime have been singled out,5) while the quest for liberal economic and political reforms has been considered one of the major driving forces behind the new wave of regionalism.6)

Notwithstanding their significance and contribution, these works leave behind an important aspect of the current wave of economic regionalism: the choice of partners and the underlying structure of the FTA network. As literature suggests, despite the general trend towards economic regionalism, countries are not indifferent to their trading partners. Since FTAs are essentially relational, any expected gains from FTAs, be they economic or political, are bound to the relative political and economic attributes of FTA partners. This is the reason why countries are selective in choosing their FTA partners, but only a few empirical works delve into the issue of choice.

Existing literature suggests that countries choose their FTA partners on the basis of relative political and economic attributes. Political scientists have identified crucial variables in the formation of FTAs such as regime type7) and alliance structure,8) but largely rely on the dyadic analysis in which the complexity of network structure is not fully addressed.

However, one major deficiency is that the literature relies on the rather strong assumption that each dyadic FTA partnership is independent of each other, while in reality FTA partnerships are overlapped and interdependent. The interdependent nature of FTA partnership, in turn, may amplify or alleviate the effect of economic or political attributes on FTA formation.

We attempt to fill this gap by utilizing the notions of “homophily” and “transitivity” in social network analysis. Homophily is the tendency to form social ties according to the similarity in actors’ attributes.9) The notion, “a friend of a friend is a friend,” captures the concept of transitivity. Transitivity refers to a situation when all pairs of three nodes have link to one another. The concept of transitivity would be useful to understand and analyze FTA formation beyond dyadic relations. Since an FTA is in essence an economic network of countries, the examination of these properties allow us to verify whether FTA network configuration is formed on the basis of their partner’s partner or similarities in political economic attributes as the literature suggests. Extant literature identifies three major attributes as the determinants of choosing FTA partners: political attributes (regime type), geographical proximity, and economic attributes (size, and sectoral composition). We examine all of these by describing the FTA network and fitting the Exponential Family Random Graph (ERG) models.

We find that the transitivity matters significantly, while other variables, except regionalism, produce mixed results. This finding confirms previous works that conjecture a strong association to seek stable relations, potential conflict reduction of the dyad, and trust building. From here the article proceeds as follows. The next section reveals the assumptions of transitivity and homophily in the literature on economic regionalism and elaborates our hypotheses. Section three provides a research design and a descriptive analysis of the existing FTA network. Section four analyzes the determinants of FTA networks by fitting the ERG models and provides a discussion of the findings. Section five discusses our findings and future avenues for research.

1)Edward D. Mansfield and Helen V. Milner, “The New Wave of Regionalism,” International Organization 53-3 (Summer 1999), pp. 589-627. 2)Preferential trade agreement (PTA) refers to a trade pact which provides preferential commercial access with a form of free trade area, custom union, and common market. Free trade agreement (FTA) is one of the PTA forms, which eliminates or reduces tariff and import quotas between signatories. In our analysis, we consider FTAs only as they are most conventional forms of PTAs. 3)Jacob Viner, The Customs Union Issue (New York: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1950). 4)Sang-Seung Yi, “Endogenous Formation of Customs Union Under Imperfect Competition: Open Regionalism Is Good,” Journal of International Economics 41-1/2 (August 1996), pp. 153-177. 5)Edward D. Mansfield, “The Proliferation of Preferential Trading Agreements,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 42-5 (October 1998), pp. 523-543. 6)Karen L. Remmer, “Does Democracy Promote Interstate Cooperation? Lessons from the Mercosur Region,” International Studies Quarterly 42-1 (March 1998), pp. 25-52. See also Mireya Solis, “Can FTAs Deliver Market Liberalization in Japan? A Study on Domestic Political Determinants,” Review of International Political Economy 17-2 (June 2010), pp. 209-237; Tony Heron, “Asymmetric Bargaining and Development Trade-offs in the CARIFORUMEuropean Union Economic Partnership Agreement,” Review of International Political Economy 17-2 (2011), pp. 209-237. 7)Edward. D. Mansfield, Helen V. Milner, and B. P. Rosendorff, “Why Democracies Cooperate More: Electoral Control and International Trade Agreements,” International Organization 56-3 (Summer 2002), pp. 477-513. 8)Edward D. Mansfield and Rachel Bronson, “Alliances, Preferential Trading Agreements, and International Trade,” American Political Science Review 91-1 (March 1997), pp. 94-107. 9)Taedong Lee and Susan van de Meene, “Who Teaches and Who Learns? Policy Learning through the C40 Cities Climate Network,” Policy Sciences 45 (Summer 2012), pp. 199-220.

Ⅱ. Theory: Homophily and Transitivity in FTA Network

An FTA has a dual-sided property. While it represents a move toward freer trade among trading partners, it discriminates against nonmembers, as preferential treatments are only extended to partners.10) This distinctive nature of economic regionalism constitutes the Vinerian terms-of-trade effect. Viner demonstrates that the creation of a new trade link between partners unambiguously increases the welfare of each partner as they are able to undermine each other’s less efficient industries.11) Yet this putatively positive effect may be offset as members are enabled to displace a more efficient outside supplier by taking advantage of the tariff preference they enjoy with a partner country.

On the basis of this discussion, the existing literature provides a number of predictions about which countries are likely to form FTAs. These predictions, in general, fall into two groups. One line of reasoning predicts that only welfare-enhancing arrangements are likely to be signed, while the other group emphasizes the political factors that buttress those arrangements. The baseline assumption of these predictions is that any FTA requires a simultaneous assent of partners. With this restriction, the welfare-enhancing group stresses that FTAs are likely to be formed if both countries are able to minimize the negative terms-of-trade effect of trade diversion. Such attributes as geographic proximity,12) the symmetry of economic size,13) and relative factor endowments14) have been singled out as key factors that determine the overall welfare impact of an FTA.

Scholars that emphasize political factors explore the conditions under which FTAs are politically feasible. Grossman and Helpman15) and Levy16) argue that FTAs are likely to be formed when they generate substantial welfare gains for the median voters or supportive interests groups. Since FTAs require the assent of all governments, it is vital for the influential social groups to be indifferent or supportive to the proposed arrangement. They argue that these conditions are likely to be met when there is a relative balance in potential trade between the partner countries, and when the countries involved have capital-labor ratios that are on the same side of the world median capitallabor ratio average.

While these discussions emphasize the political aspects of FTA formation, they nevertheless deduce the politics of an FTA from the economic attributes of participating countries. Other scholars, however, explore more direct and independent impact of political factors on FTA formation. In particular, a group of scholars argue that political regimes matter in such a way that democracies are likely to form an FTA with other democracies regardless of their relative economic attributes. One speculation for this being the case is that democracies are in general more sensitive to gross social welfare than nondemocracies so that a welfare-enhancing FTA is likely to be signed between democracies. Others speculate that electoral constraints play a crucial role for democracies being mutual FTA partners as they often find in FTAs commitment device to actions that voters would otherwise find incredible.17) Because democracies share the similar electoral constraints, they are likely to be mutual FTA partners. Notwithstanding a nuanced difference, these views conclude that regime type is a crucial factor on its own in determining FTA partnership. In sum, despite considerable disagreements regarding FTA network formation, the existing literature on economic regionalism shares a common assumption that the likelihood of FTA partnership depends upon the relative attributes of participating countries. The point of disagreement relates to whether countries are likely to form an FTA on the basis of their

The existing literature suggests that countries with similar political institutions are likely to be FTA partners. The intuition behind this reasoning is that all the expected benefits from an FTA rely on the members’ willingness and ability to liberalize trade simultaneously. The positive effect on terms-of-trade, for example, may turn into an adverse one if only one party liberalizes. Yet since trade liberalization and the concomitant policy coordination are costly, countries’ ability to form an FTA will be constrained by political institutions that may influence the relative ease of striking and maintaining a deal. For this reason, scholars note that institutional similarity matters in promoting economic regionalism.19)

Out of the various aspects of political institutions, regime type has been singled out as the major determinant. A group of scholars argue that tradeliberalizing FTAs are most likely to be formed between democracies, due to their trade policy profiles. For example, Wintrobe speculates that democracies are less rent-seeking and more prone to free trade than nondemocracies.20) Since FTAs involve mutual trade liberalization, it is natural to expect that democracies are likely to be FTA partners with each other.

Mansfield

While these logics suggest that democracies tend to pursue trade liberalization with each other, Verdier argues exactly the opposite.22) According to him, political conflicts engendered by free trade are likely to lead democratic countries to adopt more protectionist policy against each other except when intra-industry trade dominates their trade flow. Like Grossman and Helpman23) and Levy,24) Verdier argues that only those democratic countries with similar factor endowments are likely to manage free trade between them, since it will guarantee more political feasibility. This logic suggests that regime types play only a marginal or negligible role as their impact is heavily conditioned by the distribution of economic attributes. The point of disagreement here is whether regime types matter independently from other factors that may determine the likelihood of FTA partnership.

One of the key features thought to determine the likelihood of FTA formation is regionalism. In fact, the very notion of economic regionalism hinges on the importance of geographic proximity, despite its inherent elusiveness.25) Scholarly debate on the role of geographic proximity relates to the putatively negative effect of trade diversion. While Viner26) and subsequent research stipulate that trade diversion produces welfare losses, a group of scholars have expressed deep suspicion of this claim.27)

Krugman, for example, notes that despite the potential for trade diversion, an FTA between geographically proximate countries can be welfare enhancing when considering transport costs.28) Frankel draws the same conclusion that FTAs between geographically close countries are always welfare-enhancing because they create more trade among member countries while trade diversion is minimized due to intercontinental transport costs.29)

This logic is not immune to criticism. Nitsch challenges this view by noting that it holds only if intra-continental transport costs are zero.30) Since this is unlikely, he concludes, the net benefits of an FTA among geographicallyclose countries depend upon the magnitude of intra-continental transport costs relative to inter-continental costs. Bhagwati and Panagariya point out that the idea of natural trading partners is neither symmetric nor transitive.31) According to them, both the United States and Mexico, for example, may be considered natural trading partners in this logic, but in reality the relationship between them is not symmetric. While the United States can be considered as the natural trading partner of Mexico, the reverse is not true. Thus, it is hard to hold that an FTA between geographically proximate countries is ceteris paribus superior to that between more distant countries.

The debate between these two logics is an empirical one. If an FTA between geographically closer countries can help countries reap the benefits of trade creation while appeasing the negative impact of trade diversion, we should expect that the existing network of FTAs reflects geographic distribution.32) If, on the other hand, the critiques are correct in expecting a zero to minimal effect of transport costs, geographic proximity would not be an important factor in considering FTA formation.

3. Economic Attributes: Size and Sectoral Composition

At the heart of the theoretical debate about the likelihood of FTA partnership lie the relative economic attributes of potential partners. Both explanations—the welfare-enhancing theory and the political factors theory—assume a fundamental decisiveness of economic attributes in determining FTA formation. Among others, the size and sectoral composition of a national economy are the most commonly referred attributes. Yet scholars are sharply divided over whether symmetry or asymmetry in these attributes contributes to a higher likelihood of FTA formation.33)

A group of scholars argue that FTAs are likely to be formed among those countries with a similar economic size.34) The logic behind this conjecture is quite straightforward. Given that an FTA allows improved access to another market, participating countries may expect the positive change in terms-oftrade stemming from the increased exports to the partner countries.35) This benefit will increase as the partner countries have larger domestic markets. If the market sizes of participating countries are asymmetric, however, forming an FTA would be difficult since any improvement in terms-of-trade for one country would come at the expense of the other. The larger country may expect a negative change in their terms-of-trade when forming an FTA with smaller countries. Thus, to the extent that a FTA requires the simultaneous assent of both parties, it is highly likely that an FTA will be formed between those countries with similar economic sizes.

Others argue that both the welfare benefits and the political feasibility of an FTA are contingent upon the relative symmetry in the sectoral composition of national economies. Venables points out that countries with a comparative advantage closer to the world average will do better in establishing FTAs than countries with more extreme comparative advantages.36) Since the negative effect of trade diversion will vary along with the members’ factor endowments relative to the rest of the world, an FTA between countries with similar capital-labor ratios is likely to produce more benefits than losses. Conversely, an FTA between poor countries with comparative advantages below the world average may distort their true comparative advantages so that trade diversion will undermine trade creation.

Levy also demonstrates that the political feasibility of an FTA increases as the members are on the same side of the world median capital-labor ratio and when the prospect for intra-industry trade is considerable.37) Since intraindustry trade allows countries to reap gains from product diversification without having to suffer from industry dislocation, an FTA between those countries with similar sectoral composition is politically more sustainable than one where inter-industry trade is prevalent.38) Taken together, these logics suggest that FTAs are likely to be formed between homogeneous economies, in terms of (1) the size and (2) sectoral composition of the national economy.

Other scholars question these propositions. First, in light of the standard Ricardian trade model, Ethier argues that FTAs between heterogeneous economies are likely to be more welfare-enhancing than those between homogeneous economies.39) Since countries with similar economic attributes have less potential gains from trade in terms of comparative advantage, they conclude that North-South FTAs are more likely to be prevailing than NorthNorth or South-South FTAs.

Second, those who emphasize strategic considerations behind FTA formation suggest that FTAs are likely to be formed between heterogeneous economies despite asymmetric welfare gains to the participating members. In the economic models discussed above, FTAs between small-developing and large-advanced economies produce asymmetric welfare gains to the smalldeveloping economies. The expected gains for these economies range from easier access to a larger market, technology and skill transfer, to the increased potential for inward investments.40) While large-advanced economies are not able to expect similar economic gains, they nevertheless may be willing to form such an FTA out of strategic considerations, which take advantage of FTA membership as a means to enhance their voice or bypass a deadlock in a multilateral negotiation. In addition, sometimes FTAs are formed purely out of foreign policy considerations as in the US-Israel and US-Jordan FTAs.41)

In sum, the literature exhibits considerable disagreement over whether similarity or dissimilarity in economic attributes determines the choice among FTA partners. As in the case of geographic proximity, this issue is ultimately an empirical one.

Despite extensive studies looking for dyadic relations in FTA formation, theorizing triadic relations has been scant. A triad is any set of three actors. The process of triad closure implies that triads with two ties are likely to form the third ties, thus create triangles.42) Transitivity in social network analysis provides an intuitive idea that knowing something about the relationship between two actors often tells us about relationship with the third. In addition, the notion of transitivity is closely related to the putative stability in a triad. Among three actors, if actor A has ties with actor B and actor C at the same time, then the very fact that B and C do not share ties is likely to create a tension among in this triangle. Thus in order to have stable relationship among three actors, B and C are likely to have a balanced tie which ends up making stable triadic relations.43) As Wasserman and Faust argue, transitivity has been a key structural property in social network in that a third actor plays a role of brokers to reinforce group norm.44)

In the FTA context, if country A chooses country B as an FTA partner and country B chooses country C as an FTA partner, if FTA partnership is transitive, country A chooses country C as an FTA partner. There are several reasons that we expect transitivity (or triadic relationships) in FTA networks. First, conflict is more likely to be managed in a triad than a dyad because of the existence of a third party which may ameliorate trade related tensions.45) Instead of having a confrontational situation between two parties, having a third party in their FTA formation may help to have a reference point to reduce potential dyadic trade disputes. In addition, triadic relations may signal an actor’s willingness to trust other actors that its partner trusts.46) Choosing a partner’s partner as an FTA partner may reduce transaction cost in finding a trustworthy economic tie. For instance, FTA ties between the United States and Israel may have a positive signal to Canada’s willingness to trust Israel as an FTA partner given Canada already formed an FTA tie with the United States. Canada may have reviewed FTA-related interactions between Israel and the United States to assess whether Israel is a reliable economic partner and vice versa.

10)Jamie de Melo and Arvind Panagariya, “Introduction,” in Jaime de Melo and Arvind Panagariya (eds.), New Dimensions in Regional Integration (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 3-21. 11)Jacob Viner, op. cit. 12)Jeffrey A. Frankel, Ernesto Stein, and Shang-Jin Wei, “Regional Trading Arrangements: Natural or Supernatural?” American Economic Review 86-2 (January 1996), pp. 52-56. 13)Michael Michaely, “Partners to a Preferential Trade Agreement: Implications of Varying Size,” Journal of International Economics 46-1 (October 1998), pp. 73-85. 14)Wilfred Ethier, “Regionalism in a Multilateral World,” Journal of Political Economy 106-6 (December 1998), pp. 1214-1245. 15)Gene M. Grossman and Elhanan Helpman, “The Politics of Free Trade Agreements,” American Economic Review 85-4 (Winter 1995), pp. 667-690. 16)Philip I. Levy, “A Political-Economic Analysis of Free-Trade Agreements,” American Economic Review 87-2 (September 1997), pp. 506-519. 17)Edward Mansfield et al., op. cit. 18)Miller McPherson, Lynn Smith-Lovin, and James M. Cook, “Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks,” Annual Review of Sociology 27 (Summer 2001), pp. 415-444. 19)Julio J. Nogues and Rosalinda Quintanilla, “Latin America’s Integration and the Multilateral Trading System,” in Jaime de Melo and Arvind Panagariya (eds.), New Dimensions in Regional Integration (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 278-313. See also Peter J. Katzenstein, “Introduction: Asian Regionalism in Comparative Perspective,” in Peter J. Katzenstein and Takashi Shiraishi (eds.), Network Power: Japan and Asia (New York: Cornell University Press, 1997), pp. 1-44. 20)Ronald Wintrobe, The Political Economy of Dictatorship (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998). 21)Edward Mansfield et al., op. cit. 22)Daniel Verdier, “Democratic Convergence and Free Trade?” International Studies Quarterly 42-1 (March 1998), pp. 1-24. 23)Gene Grossman and Elhanan Helpman, op. cit. 24)Philip Levy, op. cit. 25)Peter J. Katzenstein, op. cit. 26)Jacob Viner, op. cit. 27)Richard E. Baldwin, “The Causes of Regionalism,” The World Economy 20-7 (November 1997), pp. 865-888. 28)Paul Krugman, “The Move toward Free Trade Zones,” in Policy Implications of Trade and Currency Zones, a symposium sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, 22-24 August 1991, pp. 7-41. 29)Jeffrey A. Frankel, Regional Trading Blocs (Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics, 1997). 30)Volker Nitsch, “Do Three Trade Blocs Minimize World Welfare?” Review of International Economics 4-3 (October 1996), pp. 355-363. 31)Jagdish Bhagwati and Panagariya Arvind, “The Theory of Preferential Trade Agreements: Historical Evolution and Current Trends,” American Economic Review 86-2 (May 1996), pp. 82-87. 32)Thomas Hale, “The de facto Preferential Trade Agreement in East Asia,” Review of International Political Economy 18-3 (2011), pp. 299-327. 33)Marks Manger, Mark A. Pickup, and Tom A. B. Snijders, “A Hierarchy of Preferences: A Logitudinal Network Analysis Approach to PTA Formation,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 56-5 (April 2012), pp. 853-878. 34)Taiji Furusawa and Hideo Konishi, “Free Trade Networks,” Journal of International Economics 72-2 (July 2007), pp. 310-335. See also Michael Michaely, “Partners to a Preferential Trade Agreement: Implications of Varying Size,” Journal of International Economics 46-1 (October 1998), pp. 73-85. 35)Kyle Bagwell and Robert W. Staiger, “An Economic Theory of GATT,” American Economic Review 89-4 (Winter 1999), pp. 215-248. 36)Anthony Venables, “Winners and Losers from Regional Integration Agreements,” The Economic Journal 113-490 (October 2003), pp. 747-761. 37)Philip Levy, op. cit. 38)Paul Krugman and Maurice Obstfeld, International Economics: Theory and Politics (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 2000). 39)Wilfred Ethier, “Regionalism in a Multilateral World,” Journal of Political Economy 106-6 (December 1998), pp. 1214-1245. 40)Maurice Schiff and Alan L. Winters, Regional Integration and Development (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.) 41)Howard Rosen, “Free Trade Agreements as Foreign Policy Tools: The US-Israel and USJordan FTAs,” in Jeffery J. Scott (ed.), Free Trade Agreements: US Strategies and Priorities(Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2004), pp. 51-77. 42)Steven M. Goodreau, James A. Kitts, and Martina Morris, “Birds of a Feather, or Friend of a Friend? Using Exponential Random Graph Models to Investigate Adolescent Social Networks,” Demography 46-1 (February 2009), pp. 103-125. 43)Xun Cao, “Global Networks and Domestic Policy Convergence: A Network Explanation of Policy Change,” World Politics 64-3 (November 2012), pp. 375-425. 44)Stanly Wasserman and Katherine Faust, Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995). 45)David Krackhardt and Mark S. Handcock, “‘Heider vs Simmel’: Emergent Features in Dynamic Structures,” Lecture Notes in Computer Science 4503 (2007), pp. 14-27. 46)Adam Douglas Henry, Mark Lubell, and Michael McCoy, “Belief Systems and Social Capital as Drivers of Policy Network Structure: the Case of California Regional Planning,” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21-3 (2011), pp. 419-444.

Ⅲ. Data and Network Description

The extant literature hypothesizes that countries are likely to form FTAs on the basis of their relative attributes. We now turn to the empirical examination of these hypotheses by describing the network structure of FTA ties in the world. In our analysis, we only consider the formal bilateral Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) notified to the GATT/WTO for the following two reasons. First, while GATT/WTO reports other types of PTAs such as customs union, more than 90% of the contemporary PTAs are FTAs. Due to its pervasiveness, we only focus on FTAs. Second, we treat existing PTAs such as the European Union (EU) and European Free Trade Association (EFTA) as single entities since a number of FTAs are formed between them and individual countries. We do not consider the PTA ties within the EU and EFTA, but we do count the FTAs between these regional groups and individual countries such as FTAs between the EU and Algeria, between EFTA and Korea, and so on. Since this choice rules out some customs unions from the beginning, we exclusively focus on FTAs for the sake of coherence.

1. Brief Description on FTA Network Evolution

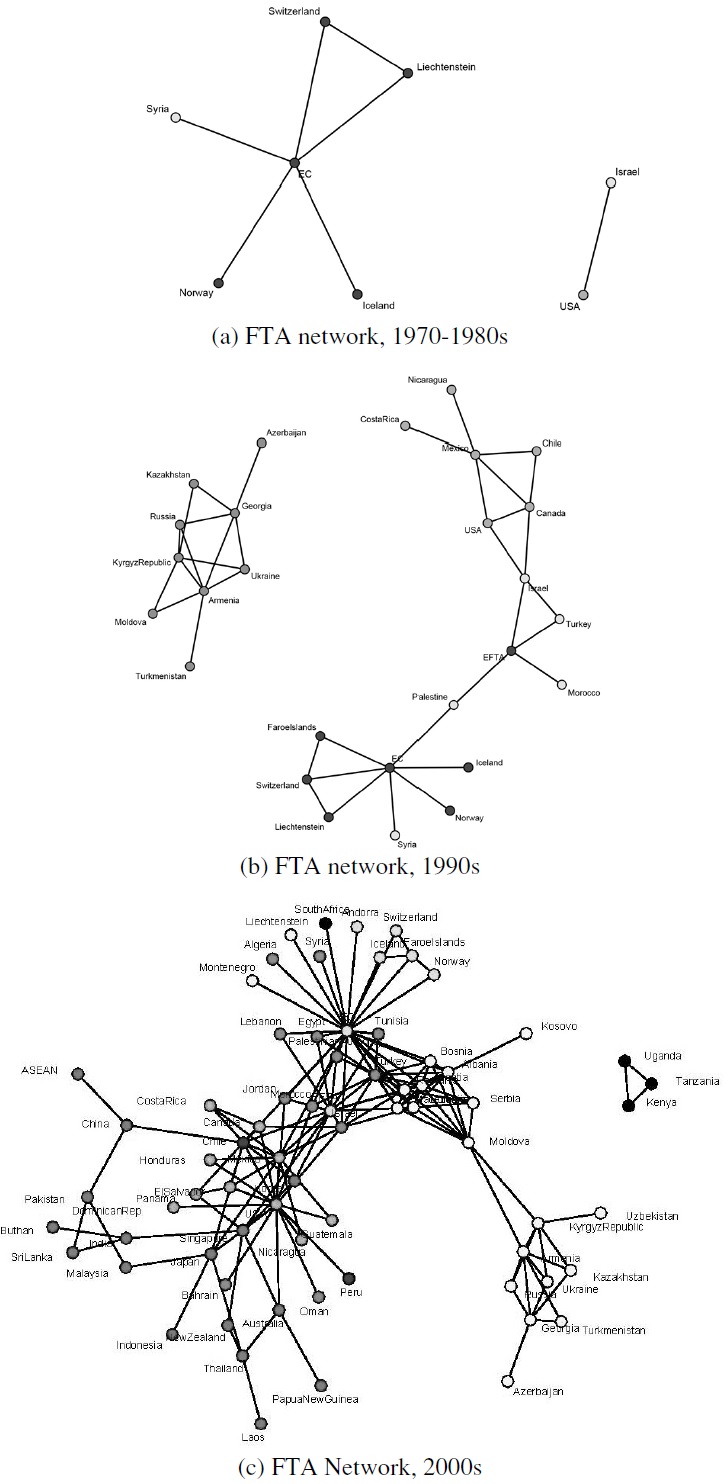

Three figures in Figure 1 present how FTA networks have evolved over time. After FTA ties were formed between the European Community (EC), Switzerland and Liechtenstein in 1973, FTA network began to grow slowly in the 1970s and 1980s, then proliferated in the 1990s, and rapidly expanded in the 2000s. Figure 1 (a) of early FTA networks (1970s-1980s) illustrates that two components were divided by EC network and US network. Star-shaped EC FTA network shows the extension of EC FTA to other European countries including Iceland and Norway. The United States formed an FTA with Israel in 1985.

Figure 1 (b) reflects the legacy of two economic and political blocs in the Cold War. One component consisted of FTAs among East European countries and Russia. After the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989, FTAs formed between Armenia and Russia, Georgia and Russia, Kyrgyz Republic and Armenia, and many others. During the transition from planned economy to market economy, former countries of the Soviet Union tended to establish trade ties with each other, forming the Commonwealth of Independent Countries (CIS).47) This European Europe FTA network has not been connected to the other component, which consists of the links between European FTAs and Americas’ FTAs.

Figure 1 (c) illustrates that the current FTA network has 71 vertices and 157 edges as of 2007. That is, 71 political economic entities around the world have 157 bilateral FTAs with each other. In the network, we find two distinctive components: one consists of densely connected 68 entities while the other comprises only three African countries (Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda). The latter is isolated from the overall network without any ties to outside countries. Previously separated Eastern European FTA networks have formed close ties to EC and other Western European countries. We also witness the rapid expansion of FTAs in Asian and American regions.

In order to verify the hypotheses derived from the literature, we categorize 71 entities with four different vertex attributes: “Regime Type,” “Region,” economic size (“GDP”), and sectoral composition (“Industrial Sector”). We collapse economic attributes of each entity into two categories (GDP and Industrial Sector) as the literature suggests and use each of these four vertex attributes as a proxy for the contending hypotheses. We first describe the existing FTA network according to these attributes before fitting the ERG model.

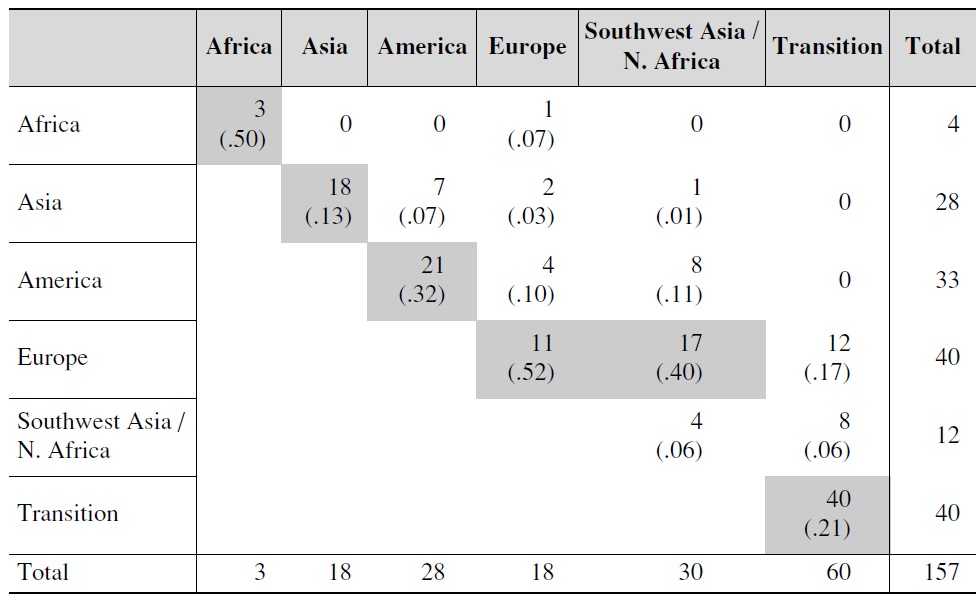

2. Political Institutional Homogeneity

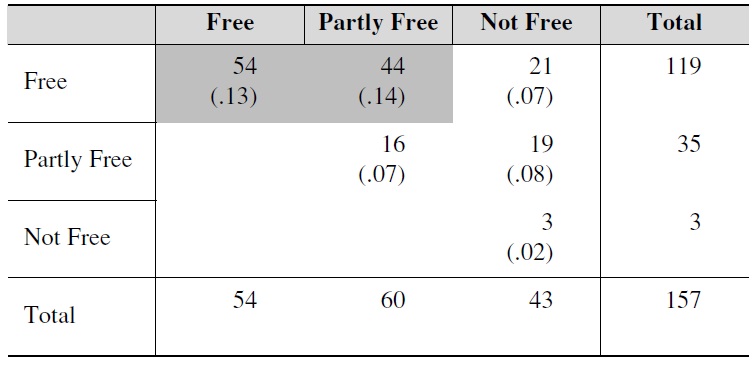

We begin with the homophily in regime type. As mentioned above, the point of analysis here is whether democratic countries tend to form FTAs with each other independently from other attributes. Our descriptive analysis exhibits a strong homophily effect among democratic countries. For the analysis, we utilize the Freedom House Democracy Index (2004), which categorizes countries into three categories: free, partly free, and not free. These three categories indicate the overall status of regime types on the basis of political rights and civil liberties ratings. In the FTA network, there are twenty-nine free countries, twenty-two partly free countries, and twenty nonfree countries.

Table 1 illustrates FTA network homophily by regime types. FTAs between free countries demonstrate strong homophily. The probability of FTA ties between free countries is 0.022 (= 54/2485), and the ratio of the total ties is 0.3446 (=54/157). Countries in partly free regime types tend to make FTA ties with free countries instead of with partly free countries or with not free countries. Countries in not free regimes show a similar pattern. Forty out of the forty-three FTA ties from not free countries are through FTA links to free countries (twenty-one FTAs) and partly free countries (nineteen FTAs). There are only three FTAs between not free countries: China-Pakistan, Kyrgyz Republic-Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyz Republic-Uzbekistan. The probability of ties between not free countries is 0.001 (=3/2485), and the ratio of ties between not free countries in the FTA network is 0.019 (=3/157). The probability of homophily by regime type is 0.029 (=(54+15+3)/2485), and the ratio of homophily by regime is 0.461 (=72/157). Homophily by regime types is mainly determined by FTA ties between free countries rather than by those in partly free or not free countries. Both non-free countries and partly free countries tend to choose democracies as FTA partners rather than countries with a similar regime type to themselves.

[Table 1.] Mixing Matrix of FTA Network by Regime Types

Mixing Matrix of FTA Network by Regime Types

In addition to the actual number of ties, the mixing ratio in parentheses show the density of each cell, reflecting the ratio of the number of observed ties to that of possible ties. That is, the mixing ratio can be measured by dividing observed ties by possible ties to get block densities. For instance, the mixing ratio of free country-free country cell is 0.13. This numeric value is calculated by dividing observed ties (54) by the number of possible ties 406 (=(28×29)/2), given that there are 29 free countries in the FTA network. A high number in mixing ratio indicates the density of ties in a given cell is also high. The z-score statistically tests the null hypothesis that the density of a given cell is not different from that of the whole network. Shaded cells which have a z-score greater than 1.96 indicate that FTAs between free countries is apparent and statistically significant.

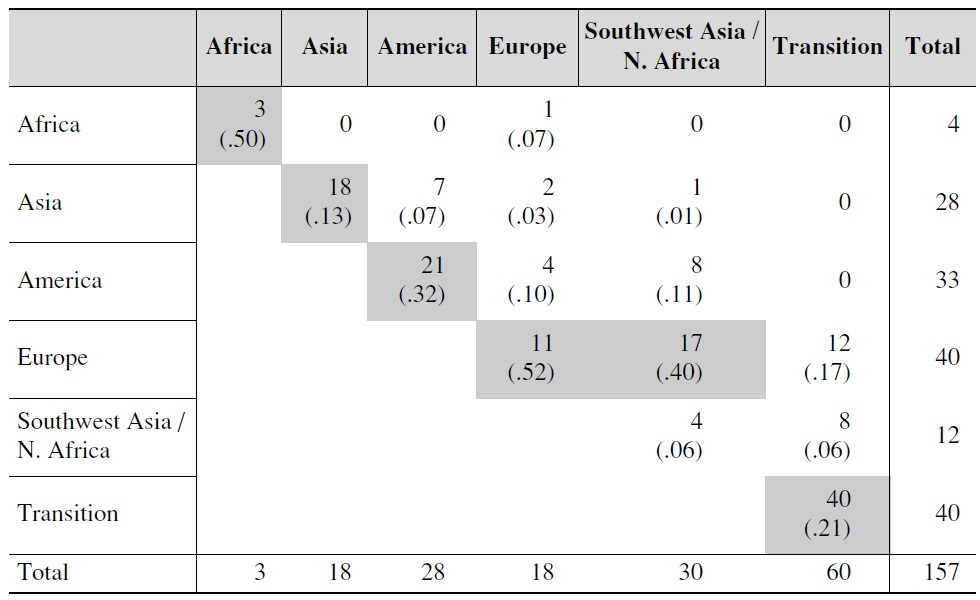

The vertex attribute “Region” tests the hypothesis on homophily in geographic proximity. If geographic proximity matters in forming FTAs as some scholars assert, then we should see the clustering of FTAs among those countries within the same region. According to the generally accepted geographic classification scheme, the world consists of eleven regions: North America, Middle America, South America, West Europe, East Europe, East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Oceania, Africa, and Southwest Asia-North Africa.48) Since the sample sizes are small in some regions like North America and South Asia, we collapsed these eleven world regions into six regions.

Figure 2 illustrates the strong tendency for FTA ties to be homophilous by region. The sub-network of FTAs in the African region is isolated within the main FTA network. Only three nodes, Uganda, Tanzania, and Kenya, form a small and separate network, not embedded within the larger network. Asian countries are mainly connected to Asian countries, while a few ties exist between Asian countries and European countries such as the EFTA-Korea and the EFTA-Singapore FTAs.49) There is no FTA links between Asian countries and countries in Africa, Southwest Asia/North Africa, and Eastern Europe transitional countries.

Transitional economies in Eastern Europe exhibit a strong homophily effect by region. Out of the sixty FTAs that involve these countries, forty FTAs are formed solely within the region. The exception is the FTA networks with Central Asian countries in which Moldova plays a crucial role in connecting these two regions. In Western Europe, the story is somewhat different as most of the FTA ties of this region are connected to countries in Southwest Asia, North Africa and transition regions (twenty-nine out the forty-seven FTA ties in Europe).

Table 2 shows that most of the FTA ties are concentrated on the diagonal except for homophily in Southwest Asia/North Africa. The probability of homophily by region is 0.003 (=77/2485), and the ratio out of the total ties is 0.493 (=77/157). Considering that most regions have a tendency to form FTAs with neighboring regions, economic geography is a noteworthy driver of FTA formation.

[Table 2.] Mixing Matrix of FTA Network by Regions

Mixing Matrix of FTA Network by Regions

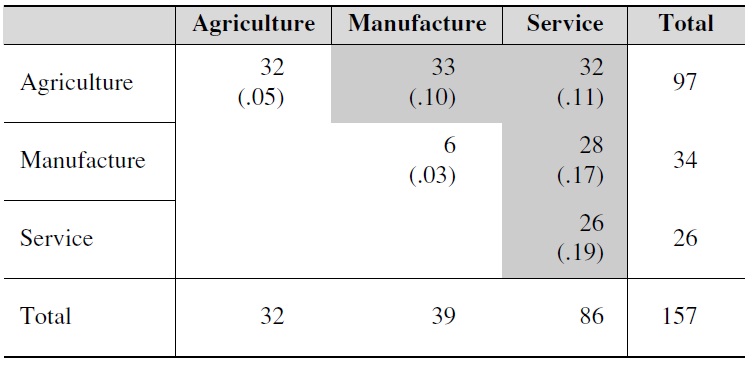

4. Homophily in Economic Attributes

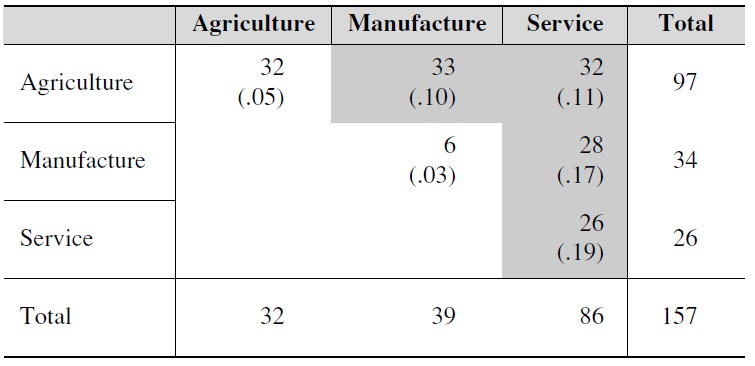

We collapse economic attributes into two categories: size and sectoral composition. In order to test the impact of economic size on FTA formation, we use GDP as a proxy for economic size.50) While GDP is a continuous variable, we categorize countries into four different groups by using quartiles. This operationalization should be considered as relative rather than absolute. As for the hypotheses on sectoral composition, we categorize each economic entity into three groups: agriculture, manufacture, and service sector-based countries. We first calculate the relative weight of each sector in GDP and compared it to the world average (3% agriculture, 28% manufacturing, and 69% service sector). The final categorization was conducted on the basis of whether a country exhibits a significantly higher portion of a certain sector than the world average. In Albania, for instance, agriculture covers 23% of GDP while manufacturing and service sector mark 22% and 56%, respectively. Therefore, we categorize Albania as an agriculture-based country. In this categorization scheme, there are thirty-five agricultural countries, nineteen industrial countries, and seventeen service-based countries.

The mixing matrix by GDP illustrates that there are two noteworthy trends in the relationship between economic size and FTA formation. First, countries tend to form FTA ties with those countries that have different economic sizes. There are thirty-one homophily FTAs in terms of economic size (ten FTAs between smallest, three between second largest, four between third largest, and fourteen between the largest economic scales). Homophily in economic size accounts for 20% of total FTAs. Second, strong gravity appears in the network. More than two thirds of the FTAs are linked to the largest economies. Countries in each category have more FTAs with countries in the 4th quartile than any other categories.

The strong gravity toward big economies casts doubts on the argument that an FTA is likely to be formed between countries with similar economic sizes. While the largest share of FTAs is between countries in the 3rd and 4th quartile of GDP, FTAs with the biggest economies are prevailing in each quartile. That is, despite the expectation that an FTA between large and small countries is less likely, the existing FTA network reveals that the majority of FTAs are formed between countries with asymmetric economic sizes. For instance, there are thirty-eight FTA ties between the biggest economies (all the economies in the first quartile) and second biggest economies (all the economies in the second quartile), which yield a mixing ratio of 0. 25 (=38 (observed ties)/ 153 (possible ties: (18*17)/2)). This finding partially supports the gravity model in the formation of FTA ties since there are dense FTA links between biggest economies and smaller economies, while relatively few FTA ties exist between the biggest economies.

The mixing matrix in Table 3 does not present evidence of homophily by industrial composition. Among others, manufacture-based economies are less likely to form FTAs with other manufacture-based economies. Only six FTAs are formed between industrial countries. The probability of homophily by industrial composition is 0.025 (=64/2485), and the ratio in total FTAs is 0.408 (=64/157). Instead, we see more FTAs between countries with different industrial compositions. Agriculture-based economies make up thirty-three and thirty-two FTAs with manufacture-based economies and service-based economies, respectively. Service-based economies also form more FTA ties with economies that have a different industrial composition.

[Table 3.] Mixing Matrix of FTA Network by Industry Types

Mixing Matrix of FTA Network by Industry Types

The descriptive analysis reported above reveals that homophily within the region and regime types are the strongest attributes in the FTA network. However, other economic attributes produce mixed results. With respect to the attribute of economic size, gravity toward larger countries, instead of homophily, turns out to be prevailing in FTA formation. Most FTAs (102 of 157) are formed between the largest economies and all others. Evidence of homophily in sectoral composition is ambiguous at best. No distinctive trend exists as far as sectoral composition is concerned.

In comparison to the economic attributes, political regime turns out to be a strong factor in determining FTA partnership. As the literature suggests,51) democratic countries tend to be active in forming FTA ties with other countries and especially with other democracies. FTA ties that involve democratic countries account for 75% of total FTAs (119 of 157), and 35% of them are between democratic countries. In sum, democracies attract more FTA ties. We now turn to a more systemic analysis of this result by fitting the ERG models.

47)Harry G. Broadman, From Disintegration to Reintegration: Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union in International Trade (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2005). 48)We use region as a proxy for geographical proximity. While geographic distance is usually used for a basic control in a gravity model, testing the homophily hypothesis requires categorical data such as continents rather than dyadic geographic distance. Sangmoon Kim and Eui-Hang Shin, “A Longitudinal Analysis of Globalization and Regionalization in International Trade: A Social Network Approach,” Social Forces 81-2 (2002), pp. 445-468. 49)Thomas Hale, op. cit. 50)We also tested the amount of trade (export + import) as another measure for economic size. Since the amount of trade is highly correlated with GDP (correlation coefficient .97), we only use the natural log of GDP. 51)Edward D. Mansfield et al., op. cit.

Mixing matrixes in the previous section are able to present the different attributes of FTA formation. We now present a more systemic analysis using the exponential family random graph model. The ERG model is a method to examine the probability of observing a particular set of network ties. This model aims to predict the joint probability that a set of edges (ties) exist on given nodes in a set of networks.52) Contrary to conventional regression models, which have focused on attributes (gender, democracy, trade amount, etc.) of the nodes (individuals, organizations, states, etc.), ERG models in social network analysis address a form of relational data. Relations in the ERG models can be presented in a dichotomous variable that indicates the propensity of ties or no ties between given nodes.53)

In the context of network formation, the FTA network is not simply random. The ERG model explores alternative hypotheses about the structure that exists and the underlying processes that generate it. In particular, the ERG model is an appropriate approach to examine the questions of how similarities in nodal attributes and network structure such as transitivity influence the absences and presences of FTA ties. For instance, ERG models can predict the probability of having a tie between countries sharing similar socioeconomic attributes, such as regime type, and how links tend to be structured among triad of countries.

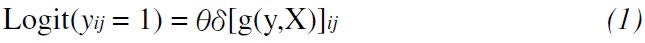

The ERG model is fitted by the following formula:

where Yij is an actor pair in Y (the random set of relations), and

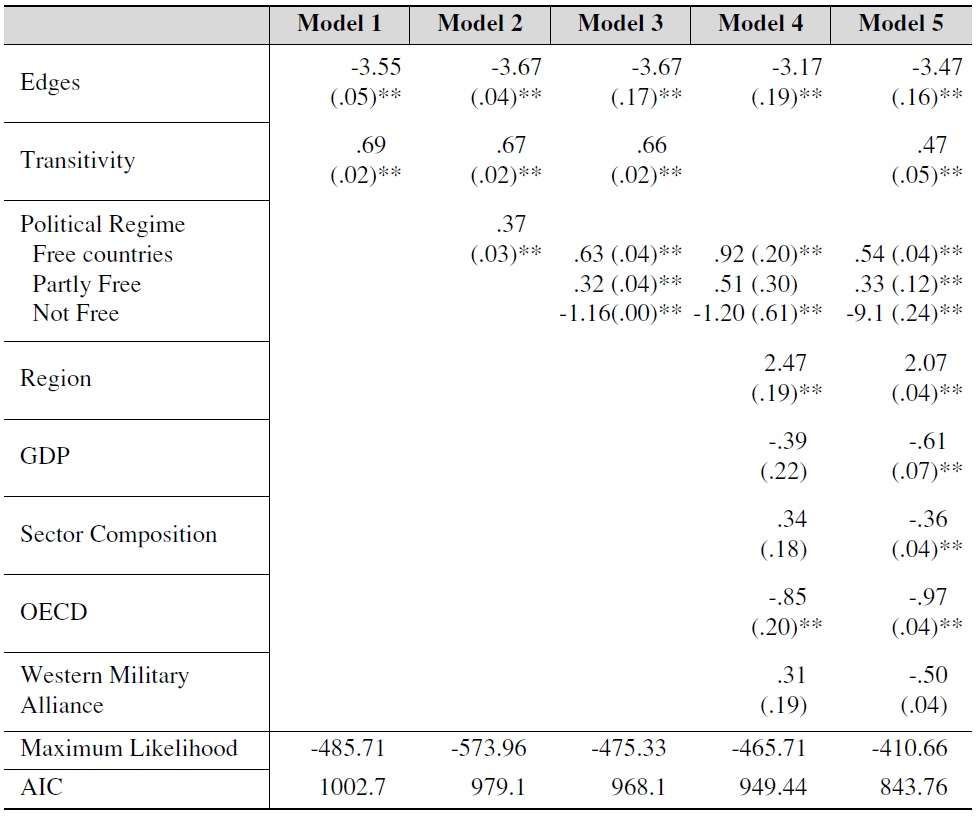

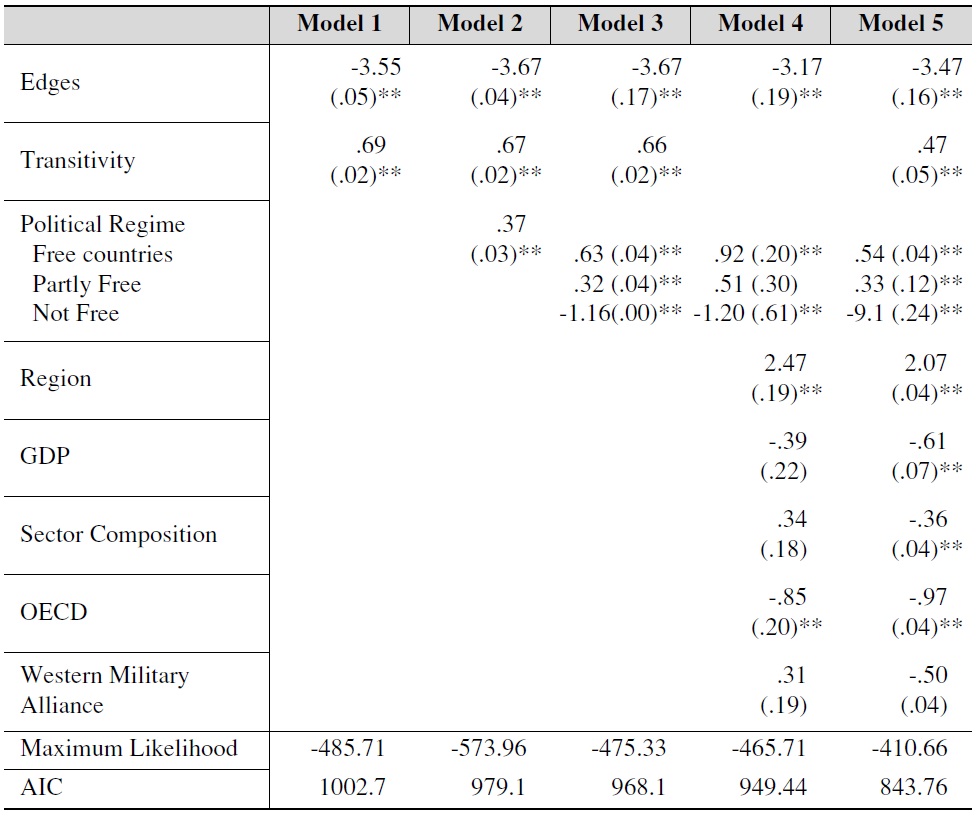

We have five models by adding an explanatory variable according to each hypothesis. In this way, we are able to test the hypotheses one by one by comparing model fits between different models. Model 1 includes edges and transitivity term in the network, which is the baseline to compare to other models. In order to test hypothesis on transitivity, we included GWESP (geometrically weighed edgewise shared partner distribution) term in Model 1. The GWESP statistic defines a parametric form of the shared partner count distribution by counting triangles when “two actors ‘share’ a partner if both have a tie to the same partner, and each shared partner forms a triangle if the original pair are tied.”

The coefficients (parameters) associated with each network variable (configuration) indicate the log-odds ratio of tie formation due to the process associated with the variable.55) For instance, a positive and statistically significant coefficient in a transitivity term in model 1 indicates that an FTA tie is more likely to form if the creation of the ties will result in a triangular configuration, which an estimated log-odds ratio is significantly different from zero at the 95% confidence level.

In Model 2, we include regime term to test the hypothesis on regime type homophily. Both terms are statistically significant at the 95% level. Homophily in political regime in model 2 is positively associated with FTA tie formation. However, this homophily term reflects assortative mixinguniform homophily within the attribute. The same tendency occurs within political regime edges, regardless of which political regime is being considered. Therefore, Model 3 disintegrates the subcategories of political regime to figure out which categories of political regime homophily promote FTA tie formation. This selective mixing within attributes’ categories is differentially likely to cross category ties.56) Model 3 shows that only free countries are positive and statistically significant in FTA formation.

[Table 4.] Homophily Models on FTA Ties

Homophily Models on FTA Ties

The inclusion of a homophily term of economic attributes such as GDP, OECD membership, and industrial composition, other control variables except for transitivity term in Model 4 does not amply improve the model fit. We also control for a military alliance factor in this full model. In order to test whether alliances of western countries form FTA ties together, we categorize countries by either military alliances of the United States and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) or non-alliance with these western countries.57) This Western military alliance variable has a negative coefficient and is not statistically significant.

Model 5 is a full model including transitivity, regime, region, GDP, OECD, sectoral composition, and western military alliance terms. The coefficients of this model indicate the log-odds of different types of ties. Among other variables, regional homophily increases the propensity of making ties, since the log-odds of a tie that is homogeneous by region is -1.4 (=-3.47+2.07), which is equal to the probability of 0.19 (= exp(-1.4)/(1+exp(-1.4)). That is, the odds of ties present within a dyad that are located in the same continent are about 19% higher than those within a dyad that are located in different continents. Other noticeable changes are decrease of coefficients in political regime homophily and region variables. The increase or decrease in the magnitude of homophily effect is associated with the propensity to form a triangular closure. If those sharing homophilous attributes are likely to form a triangle, then the magnitude of homophily effect necessary to explain observed homophily will decline. This is the case because the overall transitivity effect now will be overlapped with homophily effect. On the other hand, if transitivity effect stands independent of homophily effect, the magnitude of homophily effect necessary to explain observed homophily becomes greater. The declining homophily effect of political regimes in model 5 thus suggests that countries with similar political regimes are more likely to form an FTA cluster.

When we include the transitivity term in model 5, we see a dramatic increase in the model likelihood relative to model 4 and other previous models. Maximum likelihood estimate of model 1 and model 4, -485.71 and -465.71 respectively, decrease to that of -410.66 in model 5. AIC (Alkaike Information Criteria), an index of model fit which penalize increased number of variables, also decrease from 1002.7 and 949.44 to 843.76, which means model 5 is a better model fit than model 1 and model 4, considering the inclusion of an additional predictor.

52)David R. Hunter et al., “ergm: A Package to Fit, Simulate and Diagnose ExponentialFamily Model for Networks,” Journal of Statistical Software 24-3 (May 2008), pp. 1-29. 53)Garry Robins et al., “An Introduction to Exponential Random graph (P*) Models for Social Networks,” Social Networks 29-2 (May 2007), pp. 173-191. 54)Steven Goodreau et al., op. cit., p. 110. 55)Adam Douglas Henry et al., op. cit. 56)Ibid. 57)Douglas M. Gibler and Meredith Sarkees, “Measuring Alliances: The Correlates of War Formal International Alliance Data Set 1816-2000,” Journal of Peace Research 41-2 (March 2004), pp. 211-222.

We have analyzed the driving factors of FTA partnership. While the outburst of FTAs encourages simultaneous scholarly attention to it, scant attention has been paid to the question of which pair of countries is likely to form an FTA and for what purpose. Little research has been conducted on the potential explanation on the FTA formation in the perspective of network. This research article makes four contributions in this area.

First, methodologically we use network analysis to provide the comprehensive quantitative examination of the drivers of FTA network formation. Compared to regression analysis, network analysis allows us to examine whether existing FTA network is formed by chance and how node attributes and network configurations are associated with the FTA network. Since FTAs are in essence a network of countries, it is appropriate to apply tools developed in the field of social network analysis.

Second, thanks to network analysis method, a tendency of transitivity in the FTA network can be found. ERG models suggest that a partner of a partner is likely to be an FTA partner. The conventional thinking that FTAs tend to be bilateral relations is flawed. Triadic relations in FTAs could be more stable and tensionless.

The third implication regards empirically testing conventional driving factors of FTA formation with the concept of homophily. The existing literature suggests that countries with shared attributes are likely to form an FTA. As is summarized in section two, those attributes are institutional homogeneity, regionalism, similar economic size, and development level. We test empirically the relative strength of each of these hypotheses. Both our descriptive analysis and the ERG model estimates confirm that the homogeneity of political regimes is the most significant factor in determining the likelihood of FTA ties. Given that the majority of FTA ties are between at least partly democratic countries, it seems fair to say that democratic countries do tend to form FTAs with each other. As theory suggests, this may be the case because the institutional constraints of democracies make FTAs attractive in resolving commitment problems.

In addition, we provide evidence supporting that economic regionalism does matter in forming FTA ties. As the theory suggests, geographical proximity may allow countries to save on transport costs and alleviate some negative effects of trade diversion. While our analysis cannot confirm whether transport costs are major concerns behind the FTA formation, our results give credit to the idea that geographical proximity matters.

Unlike the expectation that countries with similar economic attributes are likely to be strong candidates for an FTA tie, the existing FTA network is not based on homogenous economic institutions. The expectation that the similarity in economic size and development level matters turns out to have only weak support. As our analysis shows, this factor contributes to FTA formation, but its impact is very weak and mixed. The majority of existing FTA ties are between developed and developing countries followed by the FTAs between developing countries. Our analysis indicates that developed countries tend not to form an FTA with each other, while economic theory suggests that FTAs are likely to be between developed countries. This finding may reflect the fact that the motivation behind forming an FTA goes far beyond economic analysis of trade creation and diversion. While our analysis cannot confirm the major motivation behind FTA formation, it nevertheless shows that FTA formation is more than simply an economic calculation, indicating the need for further research.

Our empirical analysis on choosing FTA partners tests competing theories of FTA formation and includes a new tool, social network analysis. Compared to conventional dyadic analysis, social network analysis estimates the probability of the presence and absence of FTA ties, considering network configuration such as transitivity and nodal attributes such as homophily. Our analyses suggest that birds of a feather that are located in a similar region have a tendency to flock together—to form FTA ties together. Other evidence of this research shows that it is not the similarities between states that matters but the higher levels of democracy which likely attract more FTA ties. In addition, a partner of my partner is likely to be my FTA partner. Given the potential impact of FTA ties on trade and military conflicts, examining the choice of FTA partners and its driving factors provides an opportunity to understand the political and economic implications of FTAs along with its implications to the broader theory of international cooperation. 58)

58)Edward D. Mansfield and Jon C. Pevehouse, “Trade Blocs, Trade Flows, and International Conflict,” International Organization 54-4 (Winter 2000), pp. 775-808.