“A journal is what we make of it.”1 Ideas, norms, and culture from the academic community determine the nature of the journal which publishes their works. In the field of international relations (IR), varying phenomena have occurred in different periods of time. For instance international war has become rarer in the modern period;economic interactions among countries have expanded rapidly;and newer salient issues such as terrorism, human rights, environmental issues and disease have proliferated. These changes are reflected in the content of academic journals.

Academic development is a circular process. Based upon observations of phenomena, new concepts are developed to explain their causes. Research questions are raised and hypotheses are made. To empirically investigate causal relations, hypotheses are tested qualitatively and quantitatively. New theories are developed through confirmation of these hypotheses. Consequently, theoretical, empirical and methodological criticisms are made to newly developed theories and ongoing debates on the validity of new theories occur. Similarly, some phenomena cannot be explained by extant theories. To fill this gap, new concepts and ideas are developed (Johnson and Reynolds 2012; King, Keohane and Verba 1994).

During these processes, ideas, norms and culture play a pivotal role. The field of international relations has observed the advent of new concepts for the past 60 years including: balance of power, deterrence, dependency, three images, international society, complex interdependence, hegemonic stability, non-proliferation, agent and structure, construction, integration, balance of terror, multilateralism, clash of civilization, soft power, responsibility to protect, globalization, capitalism 4.0, and others (see Morgenthau 1973; Shelling 1966; Frank 1967; Waltz 1959; Bull 1977; Keohane and Nye 1977; Keohane 1984; Wendt 1999; Ruggie 1993; Huntington 1993; Nye 2004, etc.). All these concepts and theories have been developed by academics to explain new phenomena that had occurred in the real world.

Different ideological perspectives have different ontological and epistemic orientations. They have been competing with each other to attract greater audiences. In the academic field of international relations, we have observed the rise, fall, and revival of many ideological perspectives including Marxism, idealism, (neo)realism, (neo)liberalism, (neo)institutionalism, constructivism, transnationalism, globalism, post-modernism, and so on.

Academic culture has also changed. The evolving perception of researchers makes some issues more important than others. For example, from the end of World War II to the 1960s security issues dominated the study of international relations. However, since the 1970s, economic recession, detente, oil crises, ideological disputes over economic policies, and breakdown of the Bretton Woods system made issues of international political economy more important than before. Similarly, since the 1990s, non-traditional security issues such as human security and terrorism, and other issues such as environmental degradation, global warming, resource development, energy, disease, and human rights began to attract more academic attention.

Traditional research methods and case studies were prevalent until about the 1970s. However, with the technological development prompted by the introduction of personal computers and software statistics, behavioral research methods and statistical analyses began to replace “old” traditional research methods.

Korean international studies followed a similar path to those in both the United States and non-US Western countries. Because the Korean society was a latecomer in the field of international studies, it adopted theories and ideologies developed abroad. However, during the past 50 years, the academic field of international relations in Korea has developed exponentially.2 The unique environment that Korean researchers faced made it possible for different ideas, norms and culture to emerge. For example, the idea of ‘Sunshine policy’ was articulated and the notion of a ‘Northeast Asian balancer’ was developed. Based upon past experiences and some academic developments in Korea, many discussions have taken place within the Korean political science community on the desirability and feasibility of searching for unique Korean political science and international studies (Kim and Cho 2007).

Ideas, norms and culture shared by researchers determine the content and direction of academia, including journal articles. There is a positive correlation between the academic capacity of researchers and the quality of academic works they publish. Therefore, crafting an effective academic journal depends on the quality of ideas, norms and culture shared by researchers.

There are several roles played by academic journals. First, they are pathways through which researchers can publish new ideas, theories, and data and research methods. Second, academic journals are distributed to both domestic and international audiences, which include students, researchers, professors, and government officials. They get information about concepts, theories, methods, and policies. Subsequently, they use this knowledge for future research and policy decisions.Third, academic journals accumulate research.Because of this, people can trace the history of academic works. This allows people to compare the differences and similarities between old and contemporary research. Fourth, professors can teach and train their students with academic journals. Education with journals makes students capable of performing researches of their own in the future. Finally, researchers make policy suggestions to government decision makers through academic journals. Different ideas and policy suggestions are competing to be adopted as official government foreign policies, and journals provide a link between academia and government.

Academic journals play an important role in furthering academia and also in producing respectable government policy. How can an association produce a respectable academic journal? How can we select good papers to be published? Which criteria must be applied in the selection process? How can we evaluate existing journals? These questions are important in the process of making a good journal.

1Paraphrased from Wendt (1992, 6). 2In celebrating the 50th anniversary of the foundation of the Korean Association of International Studies, Kim and Cho (2007) edited the book International Politics and Korea. In this book, Korean IR scholars traced the history of IR in Koreato evaluate the past 50 years of IR research in the country.

THE STATE OF THE ART: THE KOREAN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES

In this section, I analyze and evaluate the Korean Journal of International Studies (KJIS), the official English journal of the Korean Association of International Studies (KAIS). The KAIS is the second biggest academic political science association in Korea, next to the Korean Political Science Association (KPSA). The KAIS focuses on International Relations and Area Studies, while the KPSA is a more comprehensive association.

>

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS OF THE KJIS

Thus far, the KJIS has published 114 articles in 11 volumes. The first volume of the KJIS was published in 2003.Until 2008, only one edition was published annually. However, since 2009, two editions of each volume have been published. A plan is also in place to expand to three editions beginning in 2015. Currently, the KJIS is listed in the Korean Citation Index (KCI), which is recognized by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF).

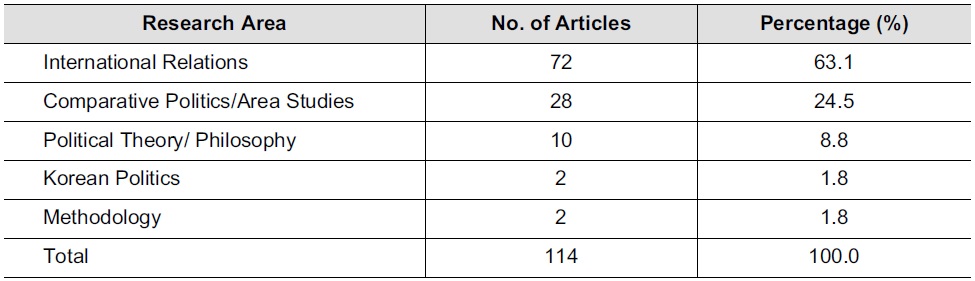

In this section, I briefly analyze all the published articles in the KJIS by placing them in five categories:research area, research region, IR subfield, IPE (international political economy) subfield, and research method. These are expressed in five different tables below.

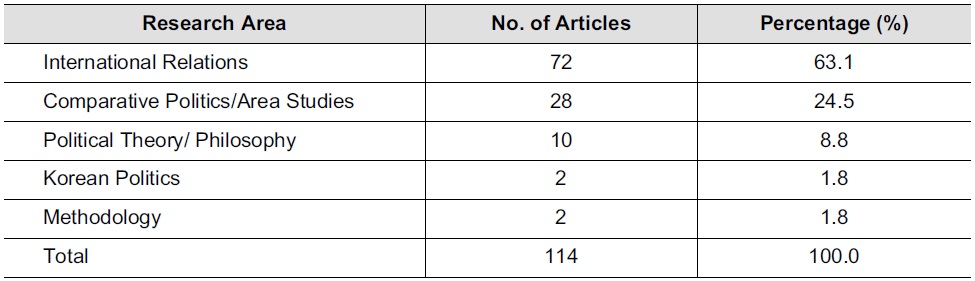

I classified all the articles into a specific research area within Political Science: International Relations, Comparative Politics/Area Studies, Political Theory/Philosophy, Korean Politics, and Methodology. As we can see in Table 1, KJIS has published 72 IR articles and 28 Comparative Politics/Area Studies articles. In the categories Political Theory/Philosophy, Korean Politics, and Methodology, ten, two, and two articles were published, respectively. Considering that the KJIS focuses on International Relations and Comparative Politics/Area Studies, these results are not surprising. Despite this fact, there are some that do not include any aspects of international studies and comparative studies. This is alarming considering the name of the journal and the scope of the journal that has been promoted.3

Research Area

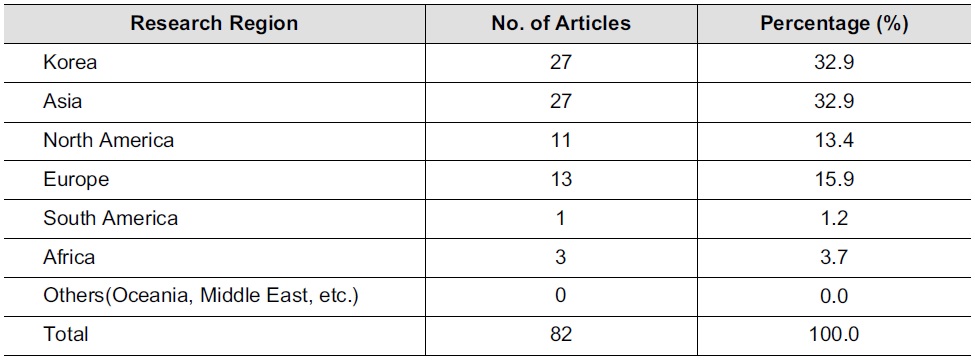

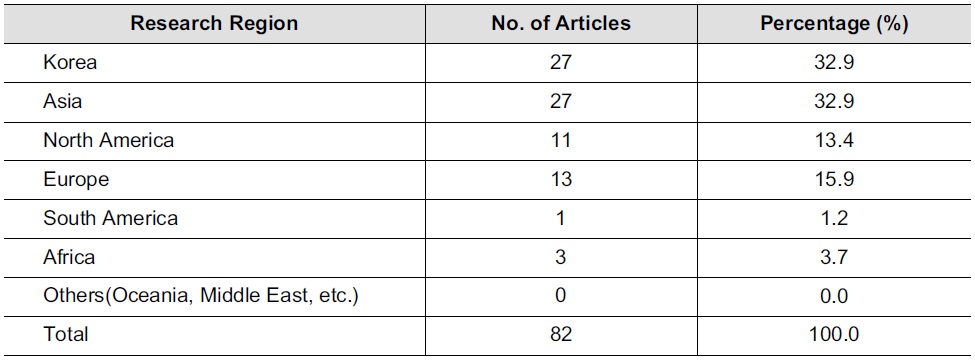

Table 2 shows the region each article discussed. The articles which are classified as ‘Korea’ deal with Korean foreign policy, inter-Korean relations, and Korean domestic political processes. ‘Asia’ covers all the Asian regions except Korea. ‘North America’ includes the United States and Canada.

Research Regions

Out of the total 114 articles published in the KJIS, only 82 articles include regional case studies. Many of the other articles are Political Theory/Philosophy articles, and Methodology articles which do not utilize any case and/or regional study. Other articles include statistical methods that cover more than one region.

As expected, the majority of the articles deal with Korean and Asian issues. However, one of the interesting results is that European studies outnumber those about North America. This may reflect the increasing number of studies in regionalism following the financial crises in Europe, and more movements toward Asian regionalism. As expected, those articles which study South American and African regions are few in number (Song 2012; Jeong 2013). Surprisingly enough, there are no studies which deal with Oceania or the Middle East. This is likely due to a lack of regional experts in Korea. Korean professors and experts usually deal with Asia, Europe, and North America, leaving a gap in their understanding of the world. Considering the close proximity of Oceania this is both surprising and alarming.

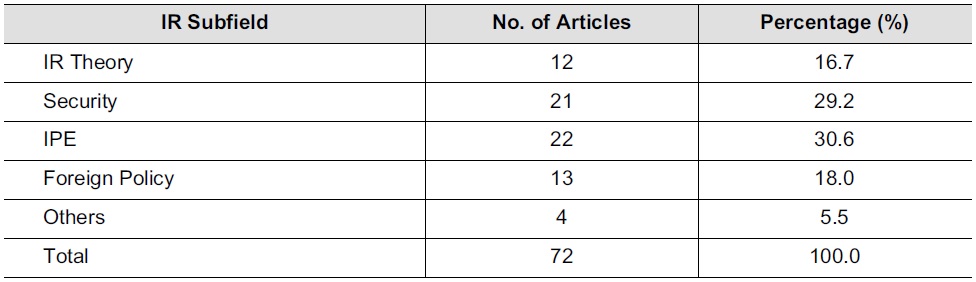

IR Subfields

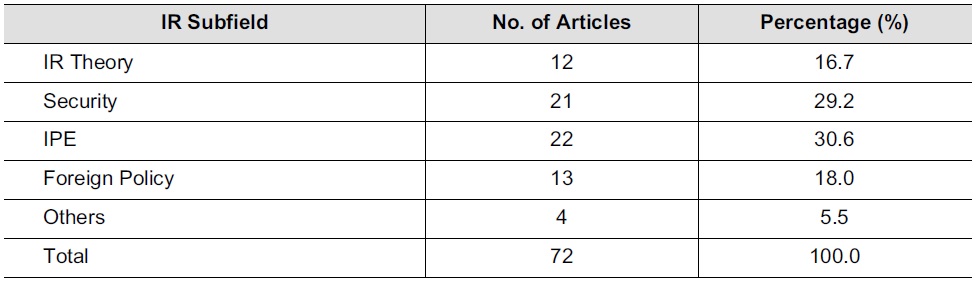

I also classified the 72 IR articles into the following IR subfields: theory, security, international political economy (IPE), foreign policy and others. The category of ‘others’ covers non-traditional IR issues such as human rights, environmental issues, refugee, immigration, etc.

One of the interesting results is thatthe number of articles in the security field and IPE is almost the same. This reflects the increasing importance of economic issues in International Relations. Since the 1990s, globalization, regionalism, financial crises and increasing economic transactions in trade,money, and investment have become major topics in the study of International Relations.

Some of the articles are pure IR theory articles. Instead of doing empirical investigations, they review, evaluate and criticize extant major IR theories such as (neo)realism, liberalism and constructivism. Also, many try to provide new concepts and theoretical interpretations to develop extant theories (Lee 2004; Ye 2004; Cho 2005; Kwon 2006; Kim 2007; Cho 2009; Cho 2010; Jung 2013).

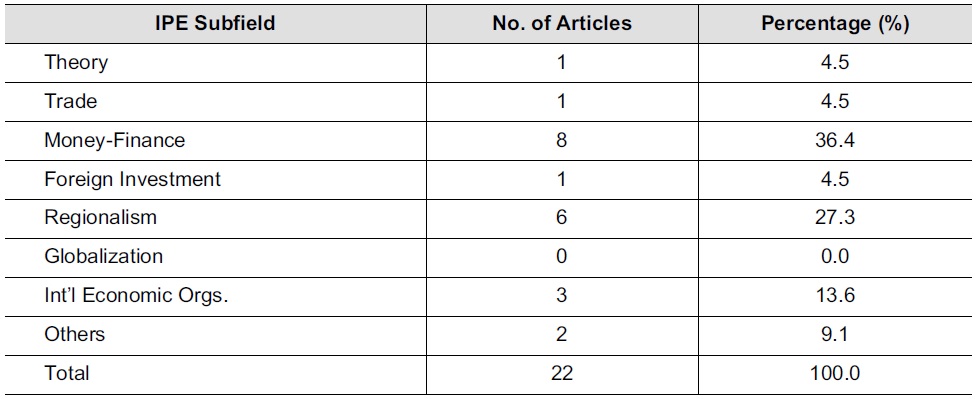

IPE Subfields

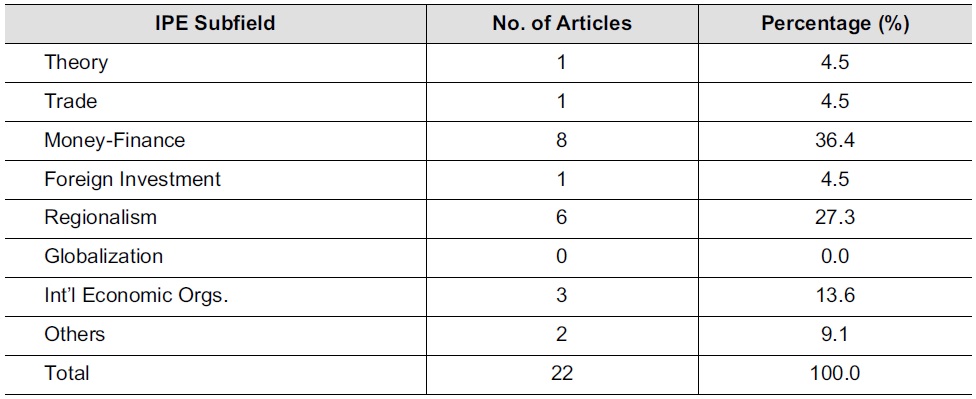

I classified the 22 IPE articles into these subfields: theory, trade, moneyfinance, foreign investment, regionalism, globalization, international economic organizations, and other non-traditional IPE issues. There were two articles which are classified as non-traditional IPE issue articles: one about soccer and HIV disease (DeLancey 2011); the other about hegemony in language testing (Yoo and Namkung 2012).

One of the 22 articles deals with trade issues. This is interesting as this field used to be the most studied IPE issue in Korea. Meanwhile, there are many articles which studied money/finance and regionalism. This reflects the fact that since the 1997 and 2008 financial crises, and following the crises in Europe, scholars in IPE have become more interested in investigating monetary and financial issues. Also, it implies that many scholars have tried to study the implications of European experiences in regionalism, comparison of European and Asian experiences in regionalism, the limitations of Asian regionalism, and ongoing debates on the Korean regionalism strategies in pursuing and joining free trade agreements (FTAs) and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Another interesting result is that there is no article on globalization, which had been heavily studied about 15 20 years ago.

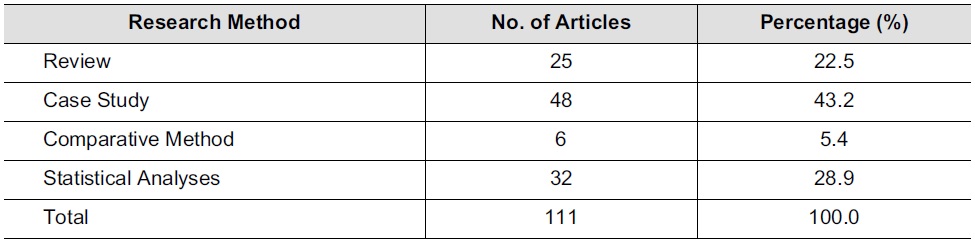

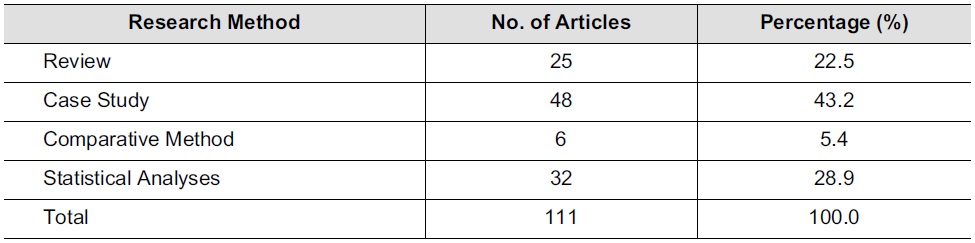

Out of 111 articles which apply any research method, 25 articles simply review existing literature without empirical investigation and hypothesis testing. Fortyeight articles utilize case study research methodology to prove the author’s arguments. Six articles are comparative and 32 articles apply descriptive and/or regression statistics for empirical research.4

>

OVERALL EVALUATION OF THE KJIS

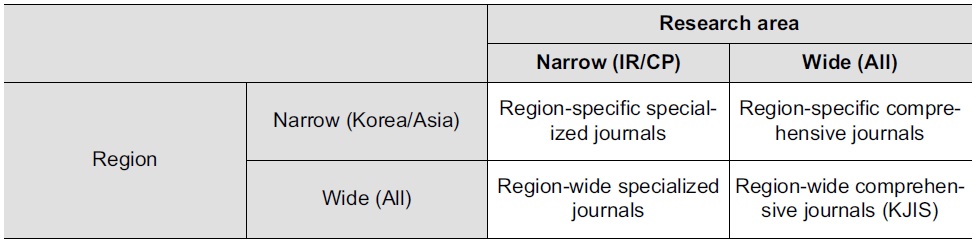

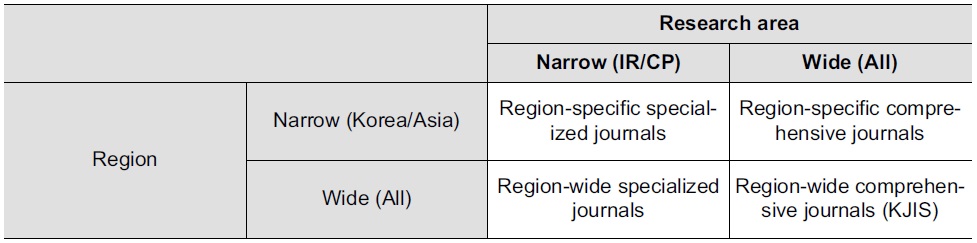

As the previous section reveals, the majority of KJIS articles can be classified as articles in the International Relations and Comparative Politics/Area Studies fields. The majority of the articles investigate Korean and Asian case studies. However, there have been many articles in the political theory/philosophy and political process fields of international studies. Also, many articles investigate non-Korean and non-Asian cases. Is this pattern good or bad for making a better journal? Do we need to confine research areas to IR and CP/Area Studies, or must we try to expand research areas? Similarly, do we need to confine research regions to Korea and Asia? To answer to these questions, we can make a two-by-two table to characterize academic journals. This table relies on two categorizations: research area and region of study. The KJIS is located in the lower right side, making it a region-wide comprehensive journal.

Some Korean political scientists may argue that we need to focus more on IR/CP areas and on the Asian region. This is due to the KJIS being published by aKorean association and in turn should primarily be concerned with exploring local salient issues. This argument makes sense. However, considering the membership composition of the KAIS, which includes Korean political scientists from various research areas, and also considering the researcher pool that are willing to submit their papers to the KJIS in the future, it might be better to maintain the current pattern of publishing the KJIS. In sum, serious consideration needs to be given to whether or not future KJIS editions should solely publish articles on purely domestic political processes with little international implications.

One interesting observation is that among the published articles, some of the articles dealing purely with IR theory reflect high-quality evaluation of extant IR theories and provide relevant new concepts and perspectives. Such articles are very useful in clarifying main ideas and arguments of IR theories, and in understanding the limitations of those theories. For example, three articles on constructivism try to provide new ideas by presenting the concept of science of constructivism (Lee 2004), comparing conventional constructivism and critical constructivism (Cho 2009), and suggesting the possibility of illiberal cooperation through constructivist methods (Cho 2010). However, one limitation of these theory-oriented articles is that they do not try to empirically prove their arguments by applying new ideas to case studies which could not be explained by extant theories.

Compared to other international studies journals published in Korea, the number of articles which apply statistical methods for empirical analyses is much larger in the KJIS. These articles account for 28.9 percent (see Table 5). Even though the majority of Korean scholars in the field of international relations had studied in the United States, where the study of statistics is a requirement in graduate studies, the number of IR and comparative politics articles that utilize statistical analyses has been much smaller in most Korean political science journals.5 Thus, it is desirable to see more articles with statistical analyses in the KJIS. This does not necessarily mean that such articles have better academic quality than those that utilize other research methods. This just means that balanced application of different research methods to different research areas promotes more academic development in the field of international studies.6

Research Methods

[Table 6.] Types of Academic Journals

Types of Academic Journals

Another interesting point is that there are several interesting and unique articles about Korea published in the KJIS. For instance,an article by Rhyu (2005) traces the origin of Korean Chaebols and argues that contrary to conventional wisdom, their origin is to be found in the Korean government’s economic policies and the Chaebols’ economic strategy rather than in political intention and rationality. In another instance, an article by Kim (2010) attempts to resolve a confusion prevalentin Korean academia surrounding the perception of ‘region’. Pointing out that Korean scholars and decision makers use ‘Asia-Pacific’, ‘Northeast Asia’, and ‘East Asia’ interchangeably without paying close attention to their different meanings and implications, Kim argues that because different concepts of ‘region’ have different historical backgrounds, strategic considerations, and political economic implications, scholars and decision makers have to be cautious and conscious in using different labels. Another highly unique Korea-related article by Cho (2006) tries to match Korean national identity with kimchi-the representative culinary symbol of Korean everyday life-by tracing the different phases of development of kimchi as a national symbol (i.e., from the beginning stage of national economic development, to the next stage of autonomous development by sectoral interests, and to the final stage of government intervention in the process of internationalization of national symbol). Finally, an article by Hayes (2010) explores the possibility of creating a Northeast Asian Biodiversity Corridor (NEABC) which would connect critical habitat in Russia, China, and the Korean Peninsula.Arguing that by following the existing model of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor (MBC), the article suggeststhe creation of a NEABC and the DMZ Peace Park would build sustainable and ecological security in the Korean peninsula. These sample works of the KJIS are extraordinary by virtue of their research topic and policy recommendations.

One alarming observation is that there are only a few articles investigating new IR research areas such as terrorism, energy, official development assistance (ODA), middle power diplomacy, public diplomacy, and human rights. Considering that the Korean government has made much effort to expand ODA and public diplomacy, and to secure energy supply and routes, one would expect to see more articles dealing with these issues. This could be due to a lack of experts in these fields, and also due to a current lack of funding. Hopefully, this can be remedied in the near future and the KJIS can publish articles in these new and expanding fields of IR.

3Some of the articles which are classified as comparative politics are just about domestic political processes such as election and voting. Because these studies have little comparative and/or international implications, it is not very clear whether it is relevant to classify them as comparative politics, See Park 2003; Yi 2005; Han 2007; Jun 2009; Shin 2009; Kim 2009; Lee 2009; Zakowski 2011; Ko and Hong 2012. 4Some of the articles classified as Comparative Method do not consciously apply Ragin (1987) type of comparisons in their analyses. Rather, they simply try to compare similarities and differences of more than two cases with similar theoretical frameworks. 5There are some statistics on research methods used in IR researches in Korea in Kim and Cho (2007). 6Recently, Mearsheimer and Walt (2013) argue that simplistic hypothesis testing by statistical models is bad for the study of International Relations. They do not argue that statistical analyses are bad per se, but that empirical studies have to be accompanied with theory development and sophistication of theoretical concepts.

A good-quality academic journal is a collective good for researchers. Therefore, making a better KJIS is a collective process that must be made by Korean political scientists and potential foreign submitters. Of course, necessary conditions do apply. First, if we believe that competition breeds quality, then there needs to be a sufficient number of submitted papers for each edition so that the end product is of much higher quality.

The second necessary condition is a good review process of submitted articles. Reviewers evaluate academic quality of submitted articles following fixed criterion: literature review, concepts and theories, data, modeling, research methods, new findings, and language skills. Talented reviewers criticize submitted articles in some aspects, and try to provide suggestions for revision. During this process, reviewers point out missing points which are not extrapolated by the author. This process is crucial if the quality of a submitted article is to be improved. Finally, it should go without saying that the review process has to be fair and transparent; academic bias and personal connection have no place in the review process.

The third necessary condition is citation. Published articles in good journals are cited more often by researchers and students. Researchers cite existing journal articles for literature review, application and development of concepts, data and cases, research methods, and theoretical arguments. Journal articles without any citation are dead articles.

The fourth condition is distribution/accessibility. For articles to be read and cited, journals have to be distributed/accessible to researchers and students, both domestically and internationally. However, distribution can be costly and accessibility affected by a journal’s format/product (i.e., print and electronic/ hardcopy and softcopy). Electronic formats and availability of an article in softcopy at a library’s digital repository, plus open and free access online to a periodical’s digital content at its official website may be useful instruments to distribute to larger audiences. Related to the issue of distribution/accessibility is awareness. Submissions to a journal and citation of its articles can only increase if more scholars know that the journal exists. Promotion through email, visibility of journal material at international conferences, word-of-mouth advertising by KAIS members and KJIS contributors, and other public relations and networking with potential readers and manuscript submitters are useful ways to garner greater publicity.

The final necessary condition to produce an effective journal is consistency. Good journals publish a limited number of articles in every issue, with issues published in a timely fashion. All the published articles utilize a similar format in the manuscript, footnotes and references. This consistency helps make a good journal a renowned one.

There are no universally accepted criteria to differentiate good journals from bad ones. Academic culture differs across countries. Ultimately, researchers perceive which one is superior and which one is substandard. At the very least, every academic society has to make considerableeffort to craft good journals of their own making. Their ideas, norms and culture are reflected in their journals.The quality of their journals reflects the quality of the researchers who make them.

Making a good journal takes time. It is a collective process. Neither a single person, nor a few people can make a good journal. Skilled researchers must submit their works. Suitable reviewers must evaluate submissions critically and conscientiously. Anacademic association must provide adequate financial support for publishing and distribution. All of these factors come into play.

In this process, the identity of submitters and reviewers must change. They must be transformed into co-makers of the journal. This change in identity will lead to a change of interests. Identity as a co-maker increases one’s affinity to the journal, thus improving the quality of each article that is published.

The KJIS is the official English journal of the KAIS. The journal has developed a lot over its short 11-year history, both qualitatively and quantitatively, and continues to attract the interest of more and more scholars in Korea and abroad, making its future bright. Nevertheless further improvements are necessary if it is to compete with other domestic and international IR journals. To be an effective periodical, its published articles must attract more attention. Content will also continue to be the most important factor in deciding the journal’s readability. As the journal strives to improve, all the members of the association should remember that the KJIS is a collective good, and that the journal is what we make of it.