The notion of a Planet Hallyuwood as a fusing of Hallyu and Hollywood allows us to look at the ways in which the South Korean film industry is linked to global markets and transnational spectators, as well as to the cross-cultural circulation of images, genres, and narrative techniques. At the same time, the term Hallyuwood enables a consideration of the relations between South Korean and U.S. cultural production. These relations have a history that predates the rapid growth and commercial success of the South Korean film industry over the past ten years. The beginnings of what would become a Planet Hallyuwood in the late 1990s— the capture of domestic and overseas market share that led to a certain form of triumphalism through 2005 and the subsequent pressures faced by the South Korean film industry due to the halving of the Screen Quota System—occur as the latest shifts in a much longer transnational history of popular cultural forms.

Recent blockbuster Korean War films themselves refer in different ways to this longer history in their representations of the early 1950s, a time not only of war and postwar poverty but of the establishment of what has become a lasting, and contested, U.S. presence in South Korea. These filmic representations of the most traumatic event in post-1945 Korean history offer something more than the latest take on the war and its immediate aftermath. The return to this event—one which rigidified a North/South division while locating South Korea firmly in the U.S.-led “free world” order—is bound up with the contested terrain traversed by Planet Hallyuwood itself. How do portrayals of the war and its aftermath in films such as

Planet Hallyuwood’s own representations of Korean history reveal the ways in which the past informs new configurations and tensions that make up the contemporary era of globalization. Paek Wŏn-dam has noted that while Hallyu can serve the interests of the state and an export-driven economy, a critical awareness that arises from Korea’s history of colonialism, division, and authoritarian regimes also finds its way into Hallyu cultural production. For Paek, such an awareness contributes to the possibility of new kinds of communality to emerge in Asia.1 While the extent and effects of such a contribution remain to be seen, Hallyu points not only to a changed domestic scene but also to a shift toward an intra-Asian cultural production and consumption that accompanies the breakdown of Cold War borders. Cultural products, for example, now flow much more easily across borders in what used to make up the Asian “free world” (Korea, Japan and Taiwan); these East Asian state formations are no longer related to each other via their separate negotiations with Hollywood and U.S. popular culture.

The success of contemporary South Korean cinema is in part related to increased domestic freedoms of the 1990s, particularly the lifting of a number of censorship restrictions, and the ability of South Korean capital to provide funds for large budget productions never before seen in the history of the South Korean film industry. The kind of editing, special effects, set/costume design, and commercialization that constitutes contemporary South Korean cinema does indeed point to a fusing of Hallyu and Hollywood. At the same time, the contemporary Korean War film displays a certain anxiety regarding both the technics of film and the newly celebrated success of Korean cinema. As we will see below, these films are informed by two overlapping tensions: (1) between the technological and the emotive; (2) between the antiwar genre and a masculinist (and commercial) desire to display action and violence. To be sure, Korean War films demonstrate a need to produce a techno-intimacy, a mass spectatorship. At the same time, they reveal a concern that technics will overtake affect and the image will become nothing more than commodity. It is, in fact, precisely this tension that has brought these films domestic box office success. These films rehearse a simultaneous desire for and rejection of action and violence, all the while casting an anxious glance at the commodification of the image upon which the success of Hallyu popular culture depends. Such a desire has informed over fifty years of literary and filmic texts dealing with the war.

Below I discuss the first blockbuster Korean War film,

1Paek Wŏn-dam, East Asia’s Cultural Choice: Hallyu (Tong Asia ŭi munhwa sŏnt’aek: Hallyu)(Seoul: P’ent’agŭraem, 2005), p. 39.

THE MARINES WHO DO NOT RETURN AND THE “FRATRICIDAL WAR”

Generic conventions are established and broken down in different ways, often by the introduction of disparate genres within the same film. While we frequently find this practice in contemporary South Korean cinema, such a mixing certainly predates the advent of Hallyu. In his discussion of South Korean “Golden Age” cinema (1950s and 1960s), for example, David Diffrient points out that “Woman’s melodrama and combat action are the main ingredients in most South Korean war films.”2 Diffrient tells us that

Here, we should recall that the melodramatic gesture, which certainly does inform a number of South Korean war films, also works on the ethical and temporal register. Many South Korean war films center on the portrayal of an ethics of familial affect (often associated, in varying degrees, with the nation) threatened both by U.S. hegemony and leftist ideology. Melodramatic chance encounters between friends and family members, moreover, operate on a temporal circularity that enables a set of natural, fated relations and affective reconciliation. In these films, that is, the moral and temporal universe of melodrama stands opposed not only to the U.S. as a constitutive outside but also to what is imagined as the North Korean position—the formulaic, and therefore non-affective, adherence to a class-based revolutionary subject engaged in what he/she misrecognizes as the historical task of liberating the Korean peninsula.

The war film itself can be divided into separate genres: antiwar and propaganda. In his discussion of

Jeanine Basinger offers an extensive list of generic requirements of the latter in her analysis of the U.S. World War II film, among them the following: a group of soldiers from different backgrounds; an objective; internal group conflicts; a faceless enemy; the absence of women after opening scenes; a discussion of why the war is legitimate; the appropriation of information and images familiar to the audience, including the use of other genres such as the horror film.5 These taxonomies allow us to see how many South Korean war films combine elements of the antiwar and propaganda film. This combination may very well reveal an ongoing battle of many filmmakers with the anticommunist censor. At the same time, this mixing underscores the importance of the fact that the Korean War has never ended (no peace treaty has been signed and the peninsula remains divided) and that it was at once a civil war and a war between global powers, carried out and largely controlled on the ground by foreign militaries (the U.S., other UN forces, and China). A desire to overcome the continuing trauma of the war, to put an end to it, manifests itself in conflicting ways: assertion of masculinist agency, linked to the ability to engage in legitimate, purposeful acts of violence (a register that contains many of the generic elements of the propaganda film); a critique of violence in general and the meaninglessness of war accompanied by a call for rapprochement and reunification (the antiwar film).

As a genre, moreover, the combat film stages death in a way that summons the spectator as survivor and witness: the film ends and the spectator remains, alive and possessing a memory of the images he/she has just viewed. Combat films thus involve a visual touching, one that often takes the form of memory and trauma, the repetition of the image. Combat films implicate spectators in this trauma even as they often work to seal violence up safely as elsewhere, away from the spectator. One is “touched” by violence insofar as one can re-imagine the image one has seen.

In Marines, the camera moves through the room of the massacred as if documenting the bodies and bearing witness. But we know, having seen the title of the film, that the marines, or at least the majority of the squad, will not return, will die. The marines, therefore, look upon their own future deaths in this scene. The question becomes how to invest these deaths with meaning. The answer: as surrogate fathers who rescue and nurture Yŏng-hŭi. It is Yŏng-hŭi, moreover, who tells the “story” of the film via voiced-over narration, making her both witness and bearer of memory. Yŏng-hŭi thus prefigures later memories of the Korean War presented from a child’s point of view that we see in the 1970s. If we can assume that Yŏng-hŭi is alive in 1963, the film, moreover, becomes an act of mourning for the dead marines.

Like

2David Scott Diffrient, “Han’guk Heroism: Cinematic Spectacle and the Postwar Cultural Politics of Red Muffler,” in Kathleen McHugh and Nancy Abelmann eds, South Korean Golden Age Melodrama: Gender, Genre, and National Cinema (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2005), p. 163. 3Ibid., p. 154. 4Andrew Kelly, “The Greatness and Continuing Significance of All Quiet on the Western Front,” in Robert Eberwein ed., The War Film (New Brunswick and London: Rutgers University Press, 2006), p. 23. 5Jeanine Basinger, “The World War II Combat Film: Definition,” in Robert Eberwein ed, The War Film (New Brunswick and London: Rutgers University Press, 2006), pp. 38–39. 6As Christina Klein and others have pointed out, adoption is central to Cold War liberal free world culture, the constitution of a multiracial family intersecting with the calls for multiculturalism. See Christina Klein, “Family Ties and Political Obligation: The Discourse of Adoption and the Cold War Commitment to Asia,” in Christian G. Appy ed., Cold War Constructions: The Political Culture of United States Imperialism, 1945–1966 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2000), pp. 35-66. In U.S. films such as Steel Helmet (Samuel Fuller, 1951) the birth of an international family shores up a Cold War masculinity. The relationship between the gruff, cynical Sgt. Zack and the orphaned Korean boy nicknamed “Short Round” (a bullet that fires too early and goes astray) points to the constitution of the inter-national Cold War family. In fact, Short Round is seeking a father, and, it seems, Zack is seeking a son. The quick bond they form allows Short Round to move from “gook” to “South Korean.” The figure of the orphan is also central in War Hunt (Denis Sanders, 1962) and The Young and the Brave (Francis Lyon, 1963).

T’AEG?KKI AND TITANIC: EFFECTS AND AFFECTS

The Korean War films that have been so important to Hallyu over the past decade play out a tension in genre already set in motion in “Golden Age” films portraying the war. They are at once intensely masculinist while melodramatic. They are also anti-war while allowing for a certain pleasure to be taken in the display of violence and action.

The building of the ship

Modern warfare is informed by a similar tension between the human and the technological (here, the weapon).8 It should come as no surprise that

Both

Chin-sŏk, image-narrator of

The combat film as a genre, in both its antiwar and propaganda inflections, has always been marked by the homosocial. It should come as no surprise that the relationship between Chin-t’ae and Chin-sŏk, the two brothers played by the stars Chang Tong-gŏn and Wŏn Pin in

The opposition of naturalized familial relations to state/ideology is nothing new, as we see, for example, in Yun Hŭng-gil’s well-known literary text “Rainy Spell” (Changma, 1973) and on the screen in its later filmic adaptation (Yu Hyŏng-mok, 1979). In Yun’s work, the association of one of the brothers with the north is largely attributed to his rash personality. In

7It was the film Shiri (Swiri; Kang Je-gyu, 1999) that began what would be a string of South Korean films taking over the top spots at the domestic box office. The exception was The Two Towers which narrowly beat Marrying the Mafia (Kamun ŭi yŏnggwang; Chŏng Hŭng-sun) in 2002. 8See Paul Virilio, War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception (London: Verso, 2009). 9See Laura Mulvey, Death 24x a Second: Stillness and the Moving Image (London: Reaktion Books, 2006). 10See Namhee Lee’s The Making of Minjung: Democracy and the Politics of Representation in South Korea (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009).

ONCE UPON A TIME IN SEOUL: ORPHAN AND COMMODITY

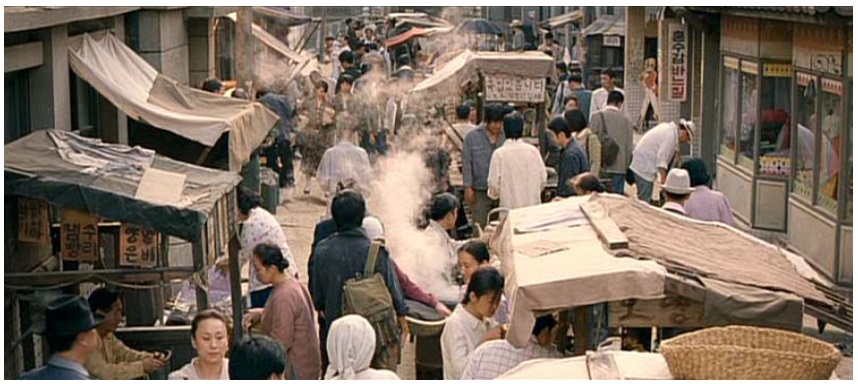

Although set in the 1950s, this film is highly aware of South Korea’s subsequent rise in global capitalism beginning in the late 1960s and the contemporary questioning of this history in the post-developmentalist 2000s. At stake, as it always has been for state-led “late developing” economies, is the relation between nation and capital. Unlike

The argument between T’ae-ho and Chong-du works itself out in relation to two figures, the young orphan Ki-dong and the young woman Su-nam, one of the street urchins co-opted by the two protagonists. Ki-dong appears one day dragging the corpse of his mother down the dirt road leading to the abandoned home the group has made their own. The group performs a funeral for Ki-dong’s mother; he is then taken in by them and cared for by Su-nam. The latter, who has been dressing as a boy, now appears in women’s clothes for the first time, a “recovery” of her femininity and her motherly instincts. She is subsequently raped by members of a rival gang, and Ki-dong is abducted.

The transformation of the street urchins into a family and T’ae-ho/Chong-du into fathers, as well as rivals for Su-nam’s affections, takes place both in relation to gendered identities and the commodity. That is, the establishing of a proper relation to commodity and profit is linked to a recovery of “natural” gender relations. Both of these concerns inform contemporary Hallyuwood production itself. The market success of Hallyu films is celebrated as emblematic of South Korea’s rise in the world, its new-found agency both economically and culturally. At the same time, the figure of Su-nam, as well as the film’s original Korean title,

In this way,

To be sure, the Hallyu phenomenon must be understood in the context of the emergence of neoliberalism in the 1990s and early 2000s. We should, however, also take into consideration the longer history of representations, filmic and literary, of which Hallyu is a part.

We have seen how Hallyu is transnational, part of a history of cross-cultural relations that constitutes an intertextuality that extends beyond South Korea’s borders. Planet Hallyuwood as a fusing of Hallyu and Hollywood represents a cross-cultural circulation of images and spectatorships that interrupts the possibility of a linear, unfolding history of national cinema. Instead, its inter-textual movement occurs as part of a negotiation of images distributed throughout the globe. To go to the multiplex in South Korea is to enter a site, every time, where both Hallyu and Hollywood appear simultaneously on different screens. Certainly Planet Hallyuwood is situated in relation to contemporary transnational capital, culture, and spectatorships. It is also historical on at least two levels. Planet Hallyuwood engages in different and changing ways with a history of images, texts, and techniques that have always circulated across borders. At the same time, both in terms of production and domestic box office popularity, Planet Hallyuwood’s articulations of the Korean War film demonstrate how the affective histories of the Cold War continue to inform the contemporary scene in divided Korea.

11As we see, for example, in Sin Sang-ok’s early A Flower in Hell (Chiokhwa, 1958) and Song Pyŏng-su’s short story “Shorty Kim” (Shori K’im, 1957). The figure of the orphan and street communities in the 1950s was also central to the works of prominent 1950s writers such as Son Ch’ang-sŏp. 12Adrien Gombeaud locates Major Sophie Jean at the center of the film. See his “Kongdong Kongbi Guyok/Joint Security Area,” in Justin Bower ed, The Cinema of Japan and Korea (London and New York: Wallflower, 2004), p. 240. As Kyung Hyun Kim points out, Joint Security Area can be seen as a “male melodrama.” See Kim’s The Remasculinization of Korean Cinema (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2004), p. 266. We thus encounter a generic mixing that extends from the early South Korean war films through Hallyu. 13In Panmunjom, Yi locates a unificatory site in a prelapsarian rural communality that opposes not only Cold War ideological bifurcation but the modern itself. Such a rejection of the modern and recovery of a tranhistorical utopia also stands at the center of Welcome to Tongmakkol. This film presents us with a village that never entered modernity, let alone an awareness of the Korean War raging around it. The film also rejects the commodity culture of the south and the technology of war that ends up targeting the village of Tongmakkol. Once they make their way to Tongmakkol, soldiers from the north, the south, and one from the U.S. must unlearn the modern and enter into the magical but real fantasy space of the villagers. This fantasy space stands outside the technics that makes it possible (the film itself) while also rejecting the targeting function of war and its scopic regime. The warring moderns are in a sense adopted by the community of this transhistorical space, which must be defended. Indeed, it is worthy of martyrdom, as we see in the deaths of the Korean soldiers protecting it from the U.S.-led attack at the close of the film.