This study investigates Korean EFL learners’ awareness and use of the English existential there-construction by examining data collected from 54 Korean EFL learners of English by means of a pragmalinguistic judgment task and a controlled discourse completion task. The results of the judgment task reveal that lower proficiency learners rated canonical sentences and existentials with a preposed locative best in the communicative situations where the use of existentials would have been most appropriate. A comparison of the ratings by more proficient learners and native speakers shows that existentials received highest ratings by both groups where they are the most natural option, while canonical sentences received significantly higher ratings by the learners. With regard to the production data, learners tended to avoid existentials, but rather relied on canonical sentences. Existentials were rarely used by lower proficiency learners and not used productively even by more proficient learners in the situations where existentials would have been the most natural option. These results suggest that Korean learners’ difficulty with the use of existentials is not merely a product of performance limitations, but attributable to limited knowledge about existentials and their syntactic alternatives in terms of contextual appropriateness. Lower proficiency learners lack such knowledge, and more proficient learners, while showing better awareness of the use of existentials, have problems as to the placement of new information when engaging in writing tasks that place lower level of demands on attention to the information status of noun phrases compared to communicative, oral tasks.

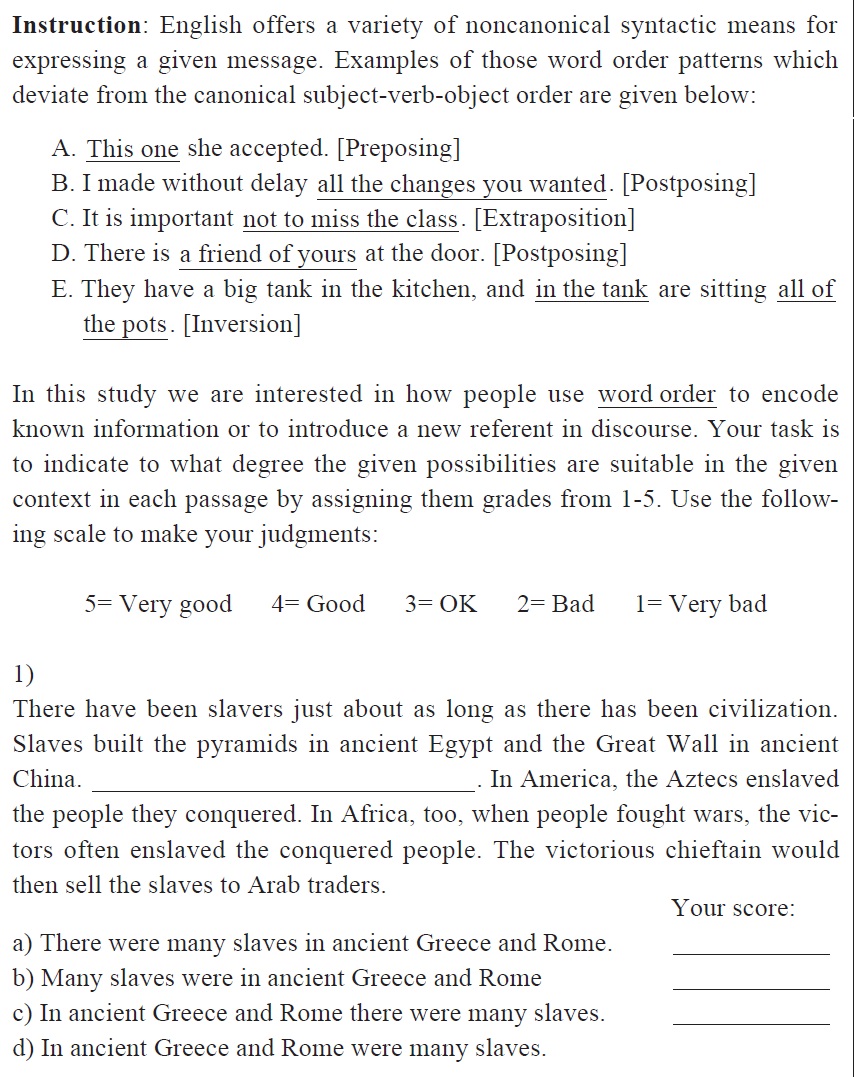

English offers a variety of noncanonical syntactic means for expressing a given proposition. Examples of those word order patterns which deviate from the canonical Subject-Verb-Object order in English are given in (1b)-(lg) below.

There are various reasons for using these noncanonical-word-order utterances: emphasizing a certain element, preserving discourse coherence, correcting misunderstanding or repairing a communicative breakdown. This discourse-pragmatic concept has come to be known as information structure or information packaging, defined as ‘a structuring of sentences by syntactic, prosodic, or morphological means that arises from the need to meet communicative demands of a particular context or discourse’ (Vallduví and Engdahl 1996: 460).

While information structure is a concept that exists in all languages, the way information structure is encoded, and the morphosyntactic means to express pragmatic effects are language-specific and vary across languages (Foley 1994: 1678). For example, English and Korean share some basic principles of information structure. Both languages favor the placing of given or familiar information before new or unfamiliar information in unmarked declarative sentences. However, the two languages differ in the way a new referent is introduced in discourse. English postposes mention of information unfamiliar to the hearer until the end of the clause by using a syntactic construction referred to as an ‘existential

On the other hand, in head-final languages like Japanese, Turkish and Korean, which have no equivalents of English existential and inversion constructions, a new referent usually appears in the immediately preverbal position when first introduced in discourse (Choi 1999; Polinsky 2009).

This difference in the syntax-pragmatic interface between the two languages is expected to present a challenge for Korean learners of English because they have to learn an entirely new mapping rule that links information from the pragmatic component to L2 syntactic positions. Not only does the marked syntactic character of particular information structural constructions such as the existential

Recent studies in the field of second language acquisition (SLA) show that information structure management is a problematic part of the L2 knowledge of nonnative speakers and that even advanced L2 learners have insufficient knowledge of the appropriate use of information structural constructions see (Callies (2008) and references cited therein). This may have a negative impact on the rhetorical appropriacy, comprehensibility, and persuasiveness of their discourse.

In this article, we present a study that examined Korean EFL learners’ awareness and use of the English existential

(i) Do Korean adult learners of English have knowledge of the appropriate contextual use of the English existential

(ii) How does their grammatical proficiency as measured by the score of standardized English tests correlate with their pragmalinguistic abilities in L2 English?

The paper is structured as follows. First, we will give a brief overview of the structural and discourse-functional properties of the English existential

II. Syntactic and Pragmatic Characteristics of Existential Constructions

In this section we will introduce some central functional principles of the organization of information in discourse and then discuss characteristics of the English existential

1. Information Status and Sentence Position

The organization of information in discourse tends to follow a socalled information principle (Biber et al. 1999: 896), i.e., given information is followed by new information. ‘Given’ information usually refers to information that is familiar from the preceding discourse or at least recoverable from the context, either directly or via inferences. The notion of context refers to both linguistic and extralinguistic dimensions, e.g., shared speaker-hearer world knowledge. ‘New’ information is not recoverable from the preceding discourse and carries the communication forward. This information principle also seems psychologically and psycholinguistically plausible, for given information usually helps to process and uncover new information. It facilitates both, the planning process of the speaker and the decoding on the part of the hearer, thereby contributing to the overall cohesion of discourse (Clark and Haviland 1977).

Prince (1992) distinguishes three basic notions of given versus new information, which in turn constitute the three primary factors that determine the structuring of information in English. The first two distinctions are between, on the one hand, discourse-old and discourse-new information and, on the other hand, hearer-old and hear-new information. Discourse-old information is that which has been explicitly evoked in the prior discourse (or its situational context), whereas discourse-new information is that which has not been previously evoked. Hearer-old information is that which, regardless of whether it has been evoked in the current discourse, is assumed to be known to the hearer, while hearer-new information is assumed to be new to the hearer. These two dimensions can be seen as a matrix of cross-cutting dichotomies (cf. Birner 1996: 82; Birner and Ward 1998: 13-16, 176-78):

Thus, consider (4):

Here, the discourse elements

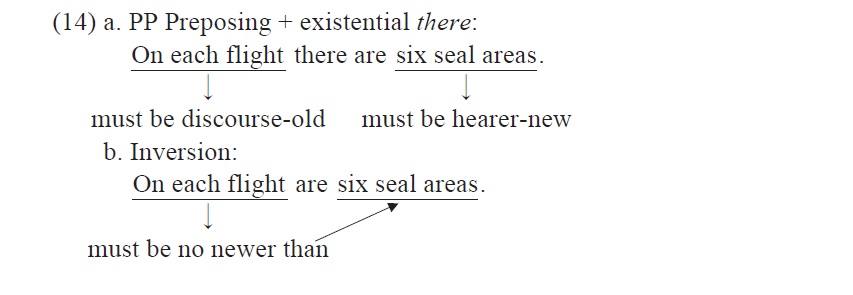

With these theoretical primitives in hand, we can now proceed to see how they apply to some of the noncanonical constructions of English. Specifically, as shown in Birner and Ward (1998), ‘preposing’ constructions (that is, those that place canonically postverbal constituents in preverbal position as in example (5a)) mark the preposed information as familiar within the discourse, while ‘postposing’ constructions (those that place canonically preverbal constituents in postverbal position as in example (5b)) mark the postposed information as new, either to the discourse or to the hearer. Finally, constructions that reverse the canonical ordering of two constituents (placing a canonically preverbal constituent in postverbal position while placing a canonically postverbal constituent in preverbal position as in example (5c)) mark the preposed information as being at least as familiar within the discourse as is the postposed information.

In short, preposing places familiar information early in the sentence, and postposing places unfamiliar information late in the sentence; moreover, when it is a single constituent that is noncanonically positioned, the constraint is absolute, whereas when two arguments are noncanonically positioned, (in particular, when their canonical positioning is reversed), it is their relative information status that is relevant. Birner and Ward (1998) show that this situation holds for all constructions in English that involve the noncanonical placement of one or more constituents. In this paper, we concentrate on a particular postposing construction in which the logical subject is postposed and the expletive

2. English there-constructions

Existential sentences can be classified into two major types based on their structural property: bare existentials and extended existentials (Ward et al. 2002: 1393-4). Bare existentials contain

Bare existentials normally have no non-existential counterpart: compare

As noted by Prince (1988, 1992) and Ward and Birner (1995), the postverbal NP of the existential

In the existential

Here, the postposed NP

Here the requirement that the postposed NP represent discourse-new information is still met and the presentational

Thus, both existential and presentational

1All of the naturally occurring examples in this section are taken from Birner and Ward (1998).

III. The Existential there-construction in SLA

The role of information structure and discourse organization has been addressed with increasing interest in SLA research. However, empirical research on the existential construction in English L2 is sparse, and predominantly examined production data. Studies that investigated how learners’ knowledge of the pragmatic restrictions of the existential construction and contextual use correlate are virtually non-existent. In this section we will review previous studies on the use of syntactic devices of reference introduction including the English existential

Schachter and Rutherford (1979) examined compositions written in English by Chinese and Japanese speakers. Both of these languages are of the type that relies heavily on the concept of topic (topic-prominence languages (Li and Thompson 1976)). Sentences are organized around a topic-comment structure, as in (12):

What Schachter and Rutherford (1979) found was an overproduction of specific target language structures, namely

Rutherford (1983) examined ESL written production by topic-prominence L1 speakers (Chinese, Japanese and Korean) at different L2 proficiency levels and found a gradual shift in the use of topic prominence to target-like subject prominence with the speakers’ growing L2 proficiency. Additional support for typological transfer in L2 acquisition came from Sasaki’s (1990) study, which examined interlanguage constructions of English existential sentences with a locative sentential topic in written production by Japanese learners at four different proficiency levels. A controlled writing task was used to examine whether Japanese learners at different proficiency levels produce typologically different constructions. Results indicated a general shift from topic-prominence structures to subject-prominence structures with learners’ increasing L2 proficiency.

Plag (1994) presents a study of information structure in the interlanguage of advanced German EFL learners. On the basis of narratives produced by German university students of English, he investigates how the learners encode brand-new information in L1 and L2 oral production, the differences between L1 and L2 production, and how these differences can be accounted for. His results show that the German learners exhibit an interlanguage-specific encoding of brand-new information. While they have a strong tendency to introduce new referents in comment position in their L1, new referents are almost equally distributed among topic and comment position in their L2 narratives.

Palacios-Martinez and Martinez-Insua (2006) examined native and Spanish learners’ use of existential

One of the most significant findings is that Spanish EFL learners demonstrated rather higher frequency of

Kim and Heine (2011) present a similar contrastive study of native and Korean learners’ use of existential

In sum, previous studies that have examined the use of the English existential constructions by L2 learners have yielded the following results:

However, the previous studies discussed above suffer from methodological shortcomings, since they have examined the frequency of the use of the English existential constructions in oral or written productions by L2 learners. They did not use data collection means other than production and hence failed to show how learners’ (non-) use of the construction and their knowledge of the appropriate contextual use of it correlate in their interlanguage. Learners may not use the construction due to processing limitations even though they have knowledge of the appropriate contextual use of it. Or they many use it even though they are not fully aware of the pragmatic constraints on the use of it. That is, non-target-like use of the construction in production may mean either that L2 knowledge is truly non-target-like or that it is (more) target-like. But we cannot gain insight into this knowledge from production data alone. Thus a full account of the use of the existential construction in L2 English must also examine whether learners have knowledge of the appropriate contextual use of the construction and whether English native speakers and learners show different preferences for the use of pragmaticallymotivated alternative word orders expressing the same propositional content in the given communicative situations.

The present study collected data from Korean learners of English by means of a pragmalinguistic judgment task and a controlled discourse completion task, both administered in the form of written questionnaires. This section describes the tasks that were used to examine learners’ judgments and written production of the existential sentences.

Pragmalinguistic judgments are defined as judgments about the appropriateness of linguistic strategies and phrases in given contexts (Kasper and Dahl 1991), and are used in this study to find out if English native speakers and Korean EFL speakers show different preferences for the use of specific syntactic devices for reference introduction in the given communicative situations. Also, it was hoped that based on the ratings it was possible to obtain evidence as to whether the Korean learners have knowledge of the appropriate contextual use of the syntactic devices.

The participants were 54 Korean learners of English at a university in Seoul, 30 females and 24 males. They are all undergraduates in their twenties, and have learned English in an EFL context involving classroom instruction. None of the participants grew up or lived in a bilingual family, and none of them had been involved in a study-abroad program longer than a year. These 54 learners comprised three proficiency groups based on their average scores on the TOEIC and time spent in an English-speaking country. Each group had 25 participants, with the exception of the advanced group (n=14). Following Kang (2009), Level 1 (the low proficiency group) consisted of students whose average scores fell below 535 points, the mean total for TOEIC test takers in Korea (TOEIC Report on Test Takers Worldwide 2005). Level 2 (the intermediate proficiency group) included students who were in the score range of 536-699. Participants who were in the score range of 700-990 were assigned to Level 3 (the high proficiency group). In terms of time spent in an English-speaking country, the Level 1 learners had not been involved in a study-abroad program in an English-speaking country yet. The Level 2 and 3 learners had all studied English abroad, with an important difference between the two groups; the former had been on short-term programs (2-3 months), whereas the latter group consisted solely of English majors who had spent an entire academic year in an English-speaking country. The native speaker control group consists of 20 native speakers of British and American English. All are undergraduate students who were enrolled in various summer session courses at Sungkyunkwan University in 2010.

The assessment questionnaire consists of two parts: test items and a set of possible responses that could be used in the specific contexts provided. Each test item was contextualized by a short passage taken from the British component of the International Corpus of English (ICE-GB) and textbooks used in American schools. The questionnaire contained a total of 20 items, of which 10 require the existential sentence as a correct response and 10 require other sentence types. In a similar fashion to Callies (2008), below each text passage, the participants were given a set of possible responses that could be used in the specific contexts provided. They were asked to indicate to what degree the given options were suitable in the given context. To do this, their task was to rate all the alternatives by assigning them grades from 1-5 on a five-point rating scale, grade 5 for a very good option, grade 1 for an unsuitable option. A sample questionnaire including the instructions to the participant is given in (13) (The entire set of stimuli is available upon request.).

The options provided in the questionnaire were the following structures:

• Existential

The questionnaire included a very common type of extended existential, namely existentials with locative extensions (e.g.,

• Canonical word order

In view of the research findings that learners prefer non-existentials to existentials, the canonical Subject-Verb-Locative PP pattern (e.g.,

• Preposed locative with

In this alternative, the locative expression appearing in the sentence-initial position precedes the existential

• Inversion

Inversion (Locative PP-Verb-Subject) is clearly the most syntactically marked pattern in English because it involves the reversal of two arguments and of subject and verb. As mentioned earlier, there is a strict discourse constraint on inversion, and hence this structure can also be considered highly marked pragmatically. Thus, in view of its high degree of markedness, inversion is expected to be problematic for learners (Callies 2008; Kim and Kim 2010).

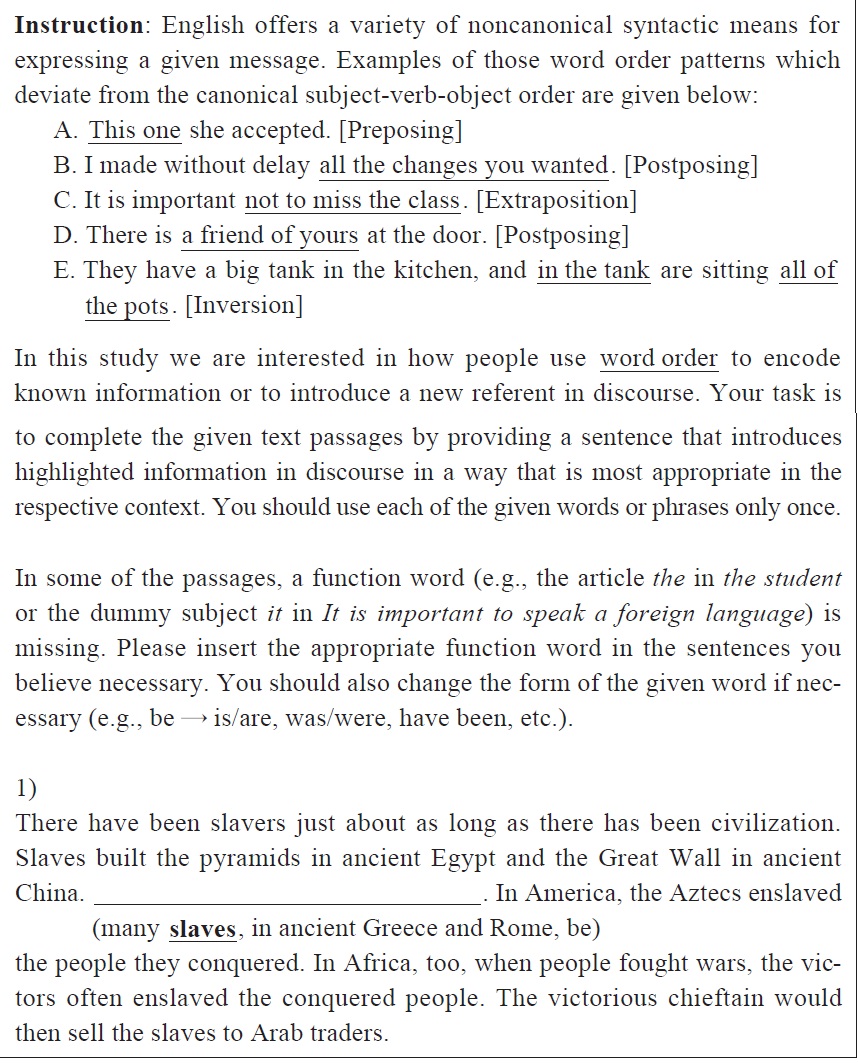

2. Production: Controlled Discourse Completion

The methods used to collect production data is a controlled discourse completion task (DCT) (see Kasper (2000) for an overview and discussion of several DCT formats). The production questionnaire, which the participants were asked to complete before their completion of the assessment questionnaire, contained a total of 20 items, of which 10 require the existential sentence as a correct response and 10 require other sentence types. The items have a controlled response format, that is, the response had to be constructed by using a set of words or phrases given in the text passage. Participants were asked to complete the given text passage by providing a sentence which introduces a new referent, i.e., highlighted information given in the passage in discourse in a way that is most appropriate in the respective situation. A sample questionnaire including the instructions to the participant is given in (15) (The entire set of stimuli is available upon request.).

The aim of this instrument was to find out which structural devices Korean EFL learners use to introduce a new referent in discourse. The major advantage of the DCT is the context and situational descriptions given clearly constrain the response so that specific linguistic structures can be elicited. While the format of the DCT is more likely to elicit written than authentic spoken language, the controlled format was believed to be well-suited to trigger syntactic constructions like existentials that are infrequent and tend to be underrepresented/avoided in data collected by means of uncontrolled, naturalistic tasks.

This section discusses the findings obtained from the pragmalinguistic judgment task and the controlled discourse completion task.

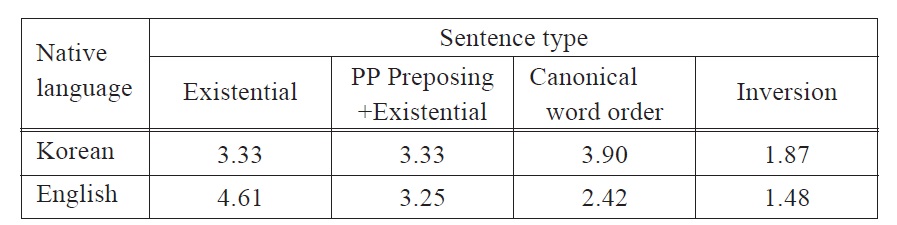

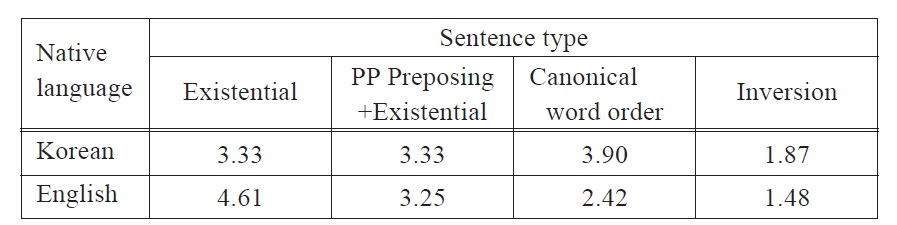

The mean scores of the rating of the 10 items which require existentials as the most preferred option are presented in Table 1.

[Table 1.] (16) Table 1. Mean scores on pragmalinguistic judgment task (learners vs. NSs)

(16) Table 1. Mean scores on pragmalinguistic judgment task (learners vs. NSs)

As shown in the table, learners and native speakers do not show clear differences in their ratings of PP preposing with an existential and inverted sentences, and both groups show the lowest acceptance ratings for inversion. In contrast, they show significant differences in the ratings for existential sentences and canonical word order sentences. While existential sentences received the highest acceptability ratings by native speakers, canonical word order sentences are the option that is rated best by learners. The comparatively low acceptability rates for existentials by learners may evidence a lack of knowledge about differences between this sentence type and other options in terms of contextual appropriateness.

A two-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to determine whether learners and native speakers treated the four options given in the questionnaire differently. Results indicate a significant main effect for group (

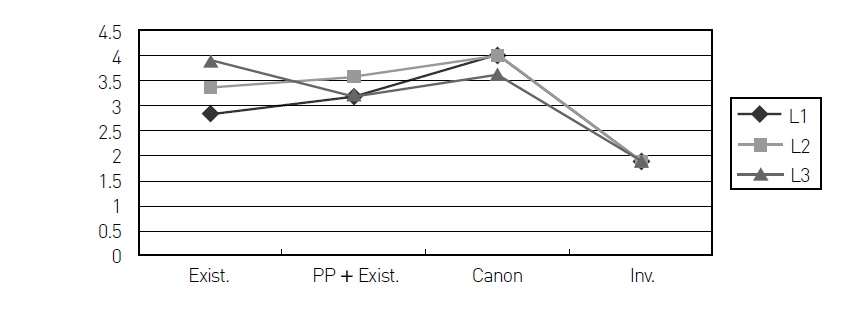

Learners’ responses were further analyzed according to proficiency levels. Low proficiency learners and more proficient learners show some clear differences in their ratings. This is illustrated in Figure 1.

A 3 × 4 repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to see whether the three groups of learners treated the four sentence types differently. The analysis reveals a significant main effect for proficiency level in the subject analysis (

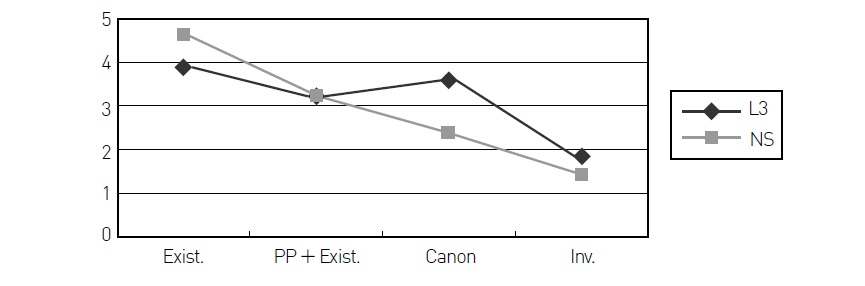

A comparison of the ratings by the Level 3 learners and native speakers shows that existentials received highest ratings by both groups, while canonical sentences received significantly higher ratings by the learners.

The results of a repeated measures ANOVA support this observation by yielding a significant main effect for group (

These results suggest that Korean learners’ difficulty with existentials is not merely a product of performance limitations, but attributable to limited knowledge about existentials and their syntactic alternatives in terms of contextual appropriateness. Lower proficiency learners lack such knowledge, and more proficient learners, while showing better awareness of the use of existentials, show a stronger preference for canonical sentences compared to native speakers where existentials are the most natural option.

2. Controlled Discourse Completion

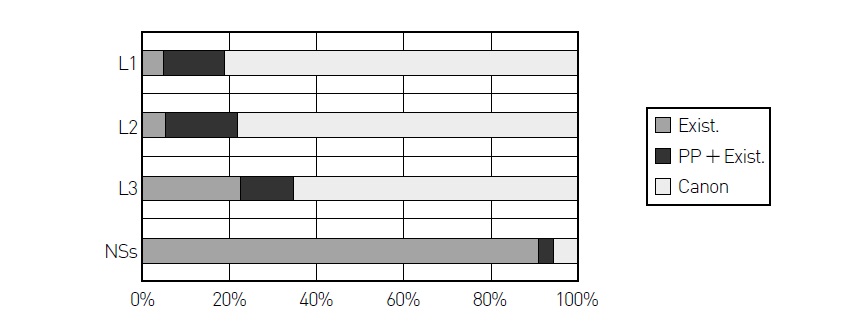

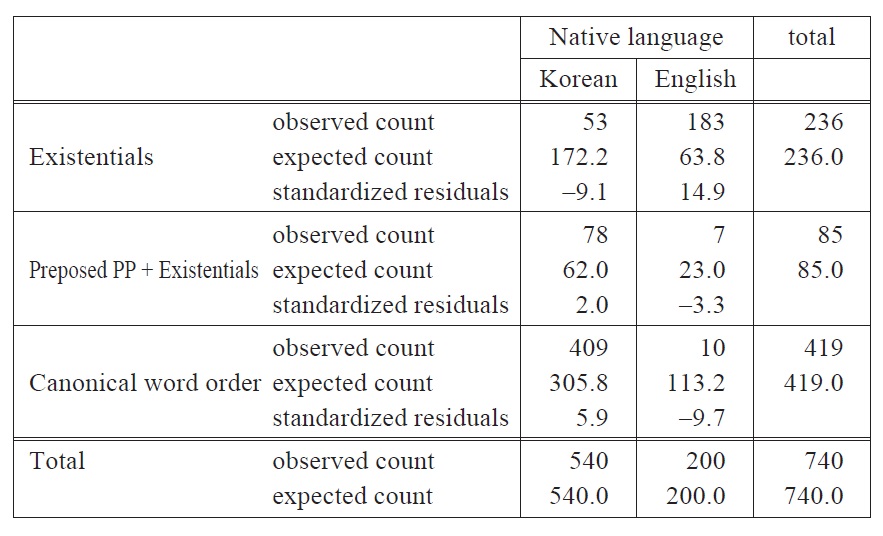

Figure 3 shows the distribution of the three sentence types across learner groups and native speakers (Inversion is not included in the analysis as no inverted structures are used by participants by both groups.). While native speakers use existential sentences 91.5% of the total 200 tokens, learners tend to avoid those sentences and rely on canonical sentences.

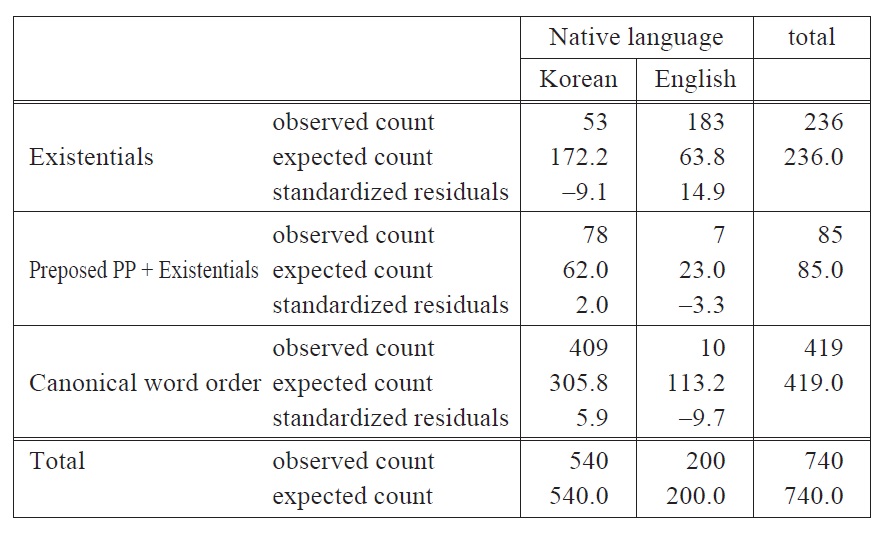

A chi-square test for this distribution reveals that the differences across native speakers and learners are significant (χ2 = 449.557,

[Table 2] (20) Table 2. Overall use of sentence types by learners and NSs

(20) Table 2. Overall use of sentence types by learners and NSs

A further analysis of the learners’ responses shows that there are significant differences across different proficiency levels (χ2 = 36.95,

The significant overproduction of canonical sentences and existentials with a preposed locative PP and the underuse of existentials by learners can be explained by a mixture of a lack of knowledge of the function and contextual effect of these sentence types and crosslinguistic influence. As mentioned earlier, English shows a strong tendency to keep informationally new material (rheme) out of the clause-initial position and place further to the right (postverbally) instead. However, learners at a lower proficiency level are not familiar with the function and contextual effect of the sentence types tested in this study and have difficulties with clearly distinguishing between them. They also overapply the Korean principles of frame-first and and rheme-before-the verb in their L2 English, indicating first language transfer at the interface of syntax and information structure. More proficient learners from Level 3, while showing better awareness of the use of existentials, have problems as to the placement of new information in production. This is in line with recent studies in SLA which found that L1 information structure plays an important role in L2 acquisition (Sasaki 1990; Carroll et al. 2000; Bohnacker and Rosén 2008; Callies 2008).

2To assess the contribution of each cell to a significant chi-square ?in our case how far the over- or underuse of a specific device contributes to the chisquare probability ? it is essential to examine and interpret the standardized residuals for each cell. Residuals are based on the difference between the observed and the expected counts and are calculated for each cell in the table. If the standardized residual is greater than 2.00, then that cell can be considered to be a major contributor to the overall chi-square probability. 3A chi-square test reveals that the differences between native speakers and the learners from Level 3 are significant (χ2 = 169.880, p = .000).

This study has investigated Korean EFL learners’ awareness and use of the English existential

However, it must be pointed out that one needs to be cautious to infer general conclusions from the data elicited in this study as they are limited due to the comparatively small number of participants and amount of data on each sentence type. Another limitation of this study lies in the non-authentic and non-communicative nature of the tasks the learners were asked to perform in this study. As emphasized earlier, the appropriate use of the English existential construction entails a command of the discourse-pragmatic constraints on the construction, and the learning of these constraints requires attention to the information status of NPs, i.e., newness of NPs. While it is important to mark and place new referents accurately in producing any kind of clear and effective discourse, the accurate marking and placement of NPs referring to new information is more important in tasks which involve real communication than noncommunicative tasks like the DCT or a sentence-level written exam. The low level of communicative demands of the DCT is likely to have an effect of lowering the need to attend to the contextual properties of NPs, resulting in the general underuse of the existential construction. In fact, previous studies on learners’ use of grammatical items such as articles have revealed that learners’ accuracy in the use of those items varies significantly from task to task and is influenced by the differing communicative demands of the tasks (Tarone 1985; Tarone and Parrish 1988). It would also be useful to examine in future research whether accuracy in the use of the syntactic devices used for reference introduction is influenced by the differing communicative demands of the tasks.