While objective reporting has become a universal standard in the news writing of the press in liberal democratic regimes, its negative effects have been closely scrutinized. An emerging concern is public cynicism, i.e., members of a society withdraw themselves from the public sphere as a result of reading objective news reports (Merritt 1998; Rosen 1996, 2001). News articles that neither reinforce positive aspects nor deflate negative ones eventually form the ambivalent attitudes of the public toward current issues. In turn, such an ambivalent attitude toward civic agendas demobilizes members of society, resulting in political disinterest. Whereas journalistic objectivity is based on a balanced view of controversial social issues, and thus, fulfills the fairness principle, journalistic routines utilizing objective reporting end up disassociating readers from the public arena. Amid this observation of political withdrawal, pundits have blamed the news media for playing a role in the erosion of civic engagement. Despite its philosophical legitimacy with regard to public interest, objective reporting has often been cited as a weakness, giving rise to political apathy among public journalists. Although journalists attempt to manage balanced views on public issues, news articles that are written through the eyes of a mere observer, without a perspective or slant, can foster political disaffection among citizens (see Jackson 1997; Woodstock 2002).

Criticizing the mannerisms of traditional journalistic approach based on objectivity, public journalists engage citizens in public affairs and community agendas. This is what makes public journalism meaningful. Such journalists see themselves not as mere transmitters of information but as a vital part of a responsible medium for revitalizing civic society. Their news reports, consequently, more often than not show a particular view or slant on civic issues and place greater importance on civic participation in political processes (Eksterowicz and Roberts 2000; Eksterowicz et al. 1998; Friedland 2001; Friedland and Nichols 2002; Glasser 1999; Haas 2007; Hass and Steiner 2001; Mcgregor et al. 1998; Merritt 1998; Rosen 1996, 2001).

Furthermore, the importance of public journalism has been amplified due to interactive communications technology. In fact, today’s journalistic approach in the online environment involves two important transformations in standardized journalistic writing. One is reflexive criticism over objective news reporting as mentioned above, and the other is more closely related to the medium itself, featuring interactivity among members of the public. What characterizes the innovated manner of news communication in cyberspace is not limited to the matter of perspectives reflected in news articles but the inclusiveness of interaction among news consumers (Tewksbury 2003). People are exposed to the real world not only through the news media but also through their conversations with fellow members of society. Some segments of the public are more active than others in finding new information about social events, becoming opinion leaders who influence those with relatively passive news search capabilities. This idea has been drawing more attention these days via the Internet, a medium that connects its users and provides a “cyberspace” for communication among them. Therefore, access to news messages and new information within events occur at the intersection between the news media and interpersonal communication (de Boer and Velthuijsen 2001; Eveland 2004; Kim et al. 1999; Kwak et al. 2005).

With these changes in mind, this paper explores how the emerging characteristics of news articles—reinforcement of a perspective and interpersonal communication—can actually enhance citizen participation in political activities. This study has two analytic objectives. First, it investigates the effects of objective journalism, comparing them to news messages that reinforce civic participation. Second, it examines how news interacts with interpersonal communication to influence civic engagement. These objectives are addressed via an experiment using college students as participants. The underlying intention of this study is to gauge the limitations of objective journalism and the potential of alternative journalism, which overtly expresses views and opinions and utilizes the technological benefit of interactive communication.

The traditional role journalists have played in society has been that of information disseminator. To enable citizens to exercise their right to access public information, journalists have focused on gathering facts surrounding important events and delivering news to as wide an audience as possible. During the years they have done so, the most important aspect of their journalistic performance has been objectivity. News articles were, and are, structured with information on who, when, where, what, why, and how (5W1H), which is known as the inverted pyramid style. There is no room for subjective views and judgments in news articles; only objective facts are delivered to readers.

Objective reporting came into existence by virtue of the invention of the telegraph and the wide spread of commercialism in 19th century America. Before objectivity became the journalistic standard, newspapers had strong partisan affiliations; instead of presenting objective journalism, they served as the “mouthpiece” of their affiliated parties. Due to the democratic development and the transformation of American society, however, including the rise of commercialism, the partisanship of major newspapers diminished. A primary reason for this transformation was the idea that journalistic objectivity would help publishers sell their newspapers more widely. As long as a newspaper was colored with a specific partisanship, the paying readership of that newspaper would be limited to those who support its party. These commercial underpinnings were important elements in the establishment of journalistic objectivity as a crucial principle of news reporting (Mindich 2000; Schudson 2001).

Despite the indispensable values entailed in journalistic objectivity, its historical development in the 20th century had its flaws and limitations. In particular, during the post-World War II McCarthy era, when unsubstantiated accusations of being a communist sympathizer were made against thousands of Americans, the news media was rigorously blamed for fulfilling the literal requirements of objective reporting while being devoid of truth-seeking. Since then, the notion that journalistic objectivity is not always the same as truth-seeking has begun to appeal strongly to American journalists and the public at large. Scholarly arguments that address the limitations of press objectivity have started to grow in the public sphere, and an array of new journalism movements have become established (Cunningham 2003).

One stream of criticism regarding press objectivity is related to the birth of public journalism and the arguments of public journalists. Although ournalistic objectivity is a primary principle of news reporting in the majority of both advanced democracies and consolidating democracies, advocates of public journalism contend that objective reporting has caused the public to become cynical and politically apathetic. These advocates, shifting from being mere observers to being active participants, have been paying special attention to the changing role of journalists. They argue that journalists should engage citizens, as well as themselves, in public issues by refusing to limit their role to that of a mere delivery medium of objective facts. This idea has been proposed to overcome the social detachment growing out of journalistic objectivity and to restore civic engagement for the revitalization of civic societies, not to give up the principle of objectivity (Rosen 1996, 2001).

Different Journalistic Approaches: Objectivity versus Reinforcement in News Articles

Numerous studies using various psychological approaches suggest that either disinterest results from an ambivalent attitude or the two go hand-inhand. When a person holds a certain attitude toward an object, s/he is likely to behave in accordance with his/her attitude. The stronger the attitude, the more stimulated the interest, leading to an expressive action (Eagly and Chaiken 1993; Katz 1981; Katz and Hass 1988). The problem with objective reporting arises as a result of this principle. Traditional journalism, especially in American culture, reflects a strict principle of objectivity. Journalists’ subjective views and judgments are excluded, and only factual information is delivered to the readers. For all its ethical values, journalism’s strong commitment to objective reporting is likely to result in detachment of news readers from society (Schudson 2001). News articles are not likely to value specific positions or stances on issues, and this leads to the formation of the readers’ ambivalent attitude toward important issues. This, in turn, facilitates disinterest in public events and issues, eventually fostering public cynicism. In general, people do not act when they do not have an opinion, and from the political point of view, such ambivalence is one of the major causes of political apathy (Katz and Hass 1988; Nelson et al. 1997). Given that one of the components characterizing public journalism is that journalists’ subjective views are reflected in news articles, one expected positive outcome of public journalism is the alleviation of public cynicism and the stimulation of civic participation in the political process.

The effect of journalistic views that reflect public journalism is not limited to reducing public cynicism about politics but can also expand to the revitalization of civic engagement. While the progressive citizens of European countries were being saturated with the New Social Movement, democratization movements in consolidating democracies such as Korea were advancing a repertoire of protest movements. Citizens with a high level of political awareness concerning a variety of public issues are likely to engage in activities that reinforce their quality of life. Issues saturating Korea’s public awareness today are not driven by the ideological cleavages that were observed in the early days of modern Korea, during which period authoritarian regimes were in control. Rather, today’s political protests touch primarily upon issues related to the quality of life and the well-being of individual citizens, which are similar to the New Social Movement in Europe. Moreover, political protest modes have become more diversified. While early democratization movements were marked by street demonstrations leading to violent conflicts, protest movements in the 21st century are more likely to utilize the Internet and non-violent symbolic demonstrations (e.g., candlelight vigils). Therefore, scholars and professionals have paid special attention to the role of journalism in this transforming political environment, and the increasing progressive demand has encouraged journalistic efforts to promote civic engagement in political activities (Bennett 1998).

Things become more complicated when it comes to journalistic approach. What if objectivity gives way to media coverage that reinforces political protests? That is to say, a question arises concerning whether a news article supporting political protest would lead to more active engagement on the part of citizens. The answer to this question may not be so simple. A key issue is the extent to which media users are politically equipped (Eveland 2004; Eveland and Shah 2003; Eveland and Thomson 2006). Individuals who are political novices with a low level of understanding on the issues involved are more susceptible to political positions that news articles focus on. A low level of political knowledge makes these people susceptible to news messages (Krosnick and Brannon 1993). When a news message is anchored in a particular stance and promotes participation in protest behaviors, it is likely that the message recipients are influenced by the message in that direction. Meanwhile, individuals who are well-politicized are immune to news messages that merely reinforce civic engagement. Their political behaviors are apt to be guided by self-organized beliefs. This group of people believes that excessively outrageous messages undermine journalistic objectivity, giving rise to the sense that participating in protests may not be a legitimate action. For these people, actual facts, delivered by the objective article, endow their political actions with a degree of legitimacy. News messages grounded in objectivity may create the feeling that “our action is legitimate enough because objective facts support such actions.” Journalistic objectivity entailing truth-seeking activities is known to affect news audiences more positively than do individual reporters’ subjective judgments.

Interaction between Journalism and Interpersonal Communication

People often discuss what they have learned from the news media with family members, friends, colleagues, neighbors, and other fellow citizens. This implies that the news media is not the only way people are exposed to the realities of society. They obtain news not only through the mass media but also through conversations with others (de Boer and Velthuijsen 2001; Robinson and Levy 1986). Interpersonal communication with regard to salient issues of concern to the public shed light on three different aspects of how news influences its consumers. The first is concerned with multiple layers of news consumers, which the two-step flow model of the media communication process once tried to identify (Katz and Lazarsfeld 1955; Lazarsfeld et al. 1944). Of members of the general public, opinion leaders on various issues of concern to the public and those with better access to the media are more likely to become influential. Personal contacts and communication as a source of information are likely to produce a stronger effect than mere exposure to the mass media. Individuals who pay close attention to the news regarding public issues become opinion leaders, disseminating information about said issues and influence their fellow citizens who pay little attention to the news media.

The significant impact of interpersonal communication on journalistic performance has been accelerated by the Internet. On the surface, the merit of this medium is undoubtedly in the C2C (citizen to citizen) interface. With this interactive mechanism, political deliberations and informal chats with fellow citizens have flourished over the Net. Despite the highly individualized lifestyles that people in contemporary society pursue, by the virtue of the Internet, they now have more opportunities than ever to communicate with others on all types of public issues. Various communication modes that enhance public deliberations, such as blogs, online cafés, and personal homepages make cyberspace an effective means for people to engage in social networking activities. The deliberative mode of news presentations in cyberspace enables news consumers to freely interact with journalists and fellow citizens to discuss public matters. Blogs and online cafés offered by both traditional mainstream media and alternative media are becoming a virtual political agora where citizen activities advance deliberative democracy and influence offline political activities.

Another political development ignited by the Internet is the way value-driven political protests are more frequently observed.1 News is not a disposable product any longer. People ponder the news to make political decisions, and political values emerge as an important determinant of political action. Online deliberations are a vibrant political activity that consolidates democracies, and communities spread their views all through cyberspace by sharing their political values with others. Although it is a common assumption that self-interest, more than anything else, is most significant to people in countries that have historically experienced economic hardship (Inglehart 1977, 1990), value-driven political participation has been frequently observed in Korea with the development of this online news environment. The public’s value-seeking activities have come to be an imperative element in the political process of consolidating democracies. The prevailing impact of online journalism on civic participation is that values outweigh the other two components of citizens’ attitudes regarding such participation (i.e., self-interest and prior experiences) (see Eagly and Chaiken 1993) due to its interactive news presentation mode and the public’s responsive activities.

Value-sharing activities of citizens are forming a cyberculture characterized by postmaterialist values. Developed from materialism, postmaterialism emphasizes a value shift from the traditional worldview. Instead of focusing on national security, economic growth, and physical sustenance, ostmaterialism places a great deal of emphasis on a wide spectrum of values that include individual freedom, self-actualization, and cosmopolitanism (Inglehart 1977, 1990). Online deliberations accelerate the impact of postmaterialist values on the political landscape through the way that postmaterialist value orientations develop a repertoire of protest activities. As evidenced in the 1960s and 1970s when the New Social Movement swept European countries, postmaterialist values have become the driving force behind a variety of protest genres.

In particular, political behavior in Korea has been significantly impacted by online deliberations; Korea is an emerging society and a leading country in terms of its IT industry and Internet connectivity. As the news environment shifts rapidly due to the Internet, the nature of news presentation and consumption is changing accordingly toward a more interactive format. Journalists and news consumers now interact to revitalize civic life instead of playing distinctly separate roles. In this environment, civic participation appears as a critical force for advancing democratic development in emerging societies. A number of previous studies suggest that online media and the changing journalistic environment illustrate the development of political conversation as a core factor that drives citizen participation in public life (Goodin and Niemeyer 2003; Kim et al. 1999; Kwak et al. 2005; Scheufele 2000). Given that interpersonal communication is a focal component that nurtures individuals’ political equipment, the divergent effects of objective and reinforcing articles on a given individual’s political participation will depend on the individual’s level of engagement in political conversation with fellow citizens. Based on these speculations, the following hypotheses were established:

1Value-driven political protest was conceptualized by Ronald Inglehart when he introduced the theory of postmaterialism. Compared with pre-war generations, those who were born after the wars experienced materialistic wealth during their maturation period. As a result, these post-war generations came to have postmaterialistic attitudes emphasizing values rather than self-interest, which drove the New Social Movement in Europe in the 1970s. A variety of genres of protest movements advocating women’s rights, animal rights, environmentalism, gay rights, and freedom and equality were driven by individuals’ political values. Inglehart distinguishes value-driven political protests from traditional labor movements; the latter is viewed to be driven by economic interests (Inglehart 1977, 1990).

The public issue examined in this study is the 2008 mad cow disease upheaval in Korea. As is widely known, Korean government’s decision to import U.S. beef fueled public anger against government officials. Public resentment concerning the issue was based on the perception that President Lee Myung Bak and his administration had given up the country’s quarantine and inspection sovereignty. Korean citizens believed U.S. beef from cattle older than 30 months contained specified risk material (SRM) that cause bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, a.k.a. mad cow disease). By holding a candlelight rally, thousands of protesters pushed the government to renegotiate with the U.S. for a ban on the importation of products potentially containing SRMs and to verify the safety of the U.S. beef supply. In spite of amendments to the U.S. beef import deal, a candlelight rally continued to be held, becoming not only a concern over citizens’ health and well-being but also a genuine political issue. The BSE crisis was an appropriate subject for this study to examine, given that this crisis had saturated the media, moving to the top of the national agenda, and that most of the public were aware of the issues raised during this crisis.

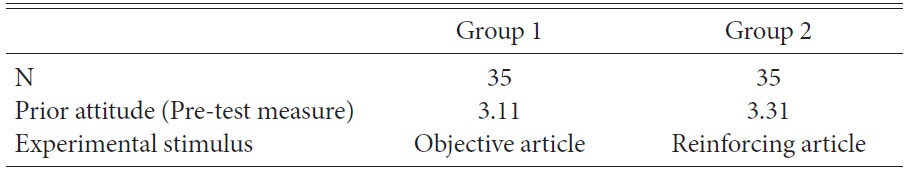

[Table 1] Description of Experimental Groups and Stimuli

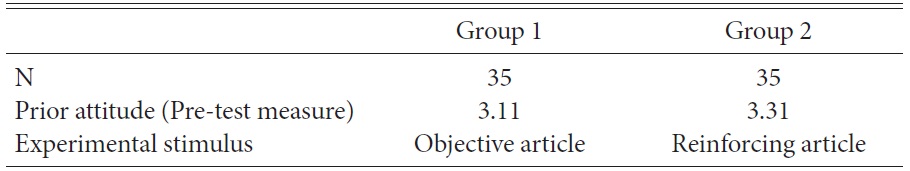

Description of Experimental Groups and Stimuli

Students taking a course in news writing at a university in Korea for the 2008 fall semester were recruited to participate in the experiment. A total of seventy students (out of seventy-seven registered students) participated. Five students who had actually participated in the candlelight vigil were excluded from the experiment. In line with the between-subject experimental design, two groups of subjects were given two different types of articles about the BSE crisis: 1) a straight news article embodying objective reporting (N = 35), and 2) a reinforcing article (N = 35). A reinforcing article is a news report that signifies a particular stance on a political issue. While an objective article gives only factual information (5w1h: what, when, where, who, why, and how), a reinforcing article reflects the reporter’s opinion (see Table 1).

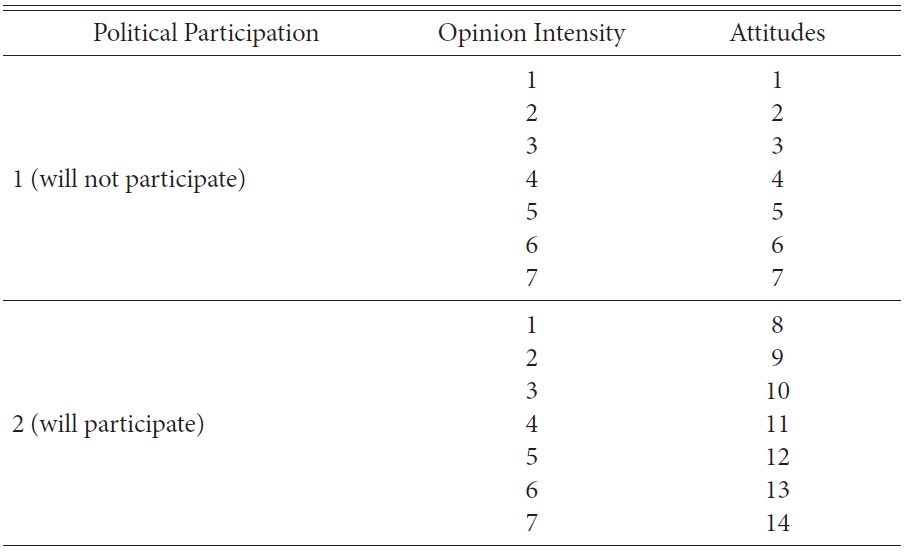

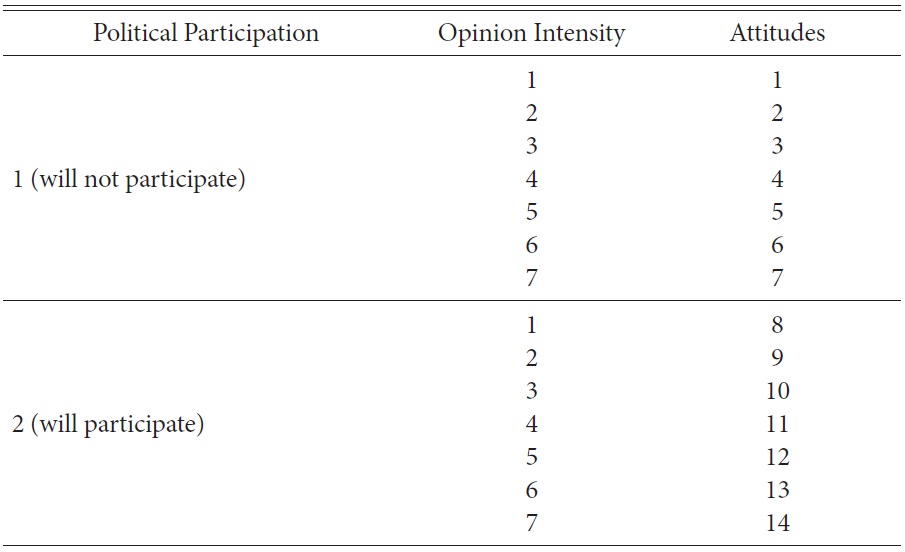

[Table 2] Recoding of Political Participation

Recoding of Political Participation

Offline newspaper reading (M = 4.01, SD = .97), TV viewing (M = 3.77, SD = 1.12), online news reading (M = 4.21, SD = .80), and conversations with others (M = 3.94, SD = .80) were measured on a 5-point scale, which ranged from “almost never” to “very frequently.” Conversations with others were measured by asking, “How often have you conversed with others about the issue?” The political ideology variable was measured by a 7‑point scale from 1 (“strongly liberal”) to 7 (“strongly conservative”) (M = 3.17, SD = 1.30); and for sex, 1 indicates male gender (N = 32) and 2 represents female gender (N = 38).

Prior to the experimental treatment, subjects’ attitude toward importation of U.S. beef was measured on a 5-point scale, from “very negative” to “very positive.” According to the T-test, the two experimental groups (i.e., objective article vs. reinforcing article) did not show a significant difference in attitude toward the issue (M = 3.11 for objective article, M = 3.31 for reinforcing article, T = .70, p = .49, two-tailed). This assured that the behavioral intention measured after the experimental treatment was not due to a prior attitude but was more likely due to the news articles read by the subjects.

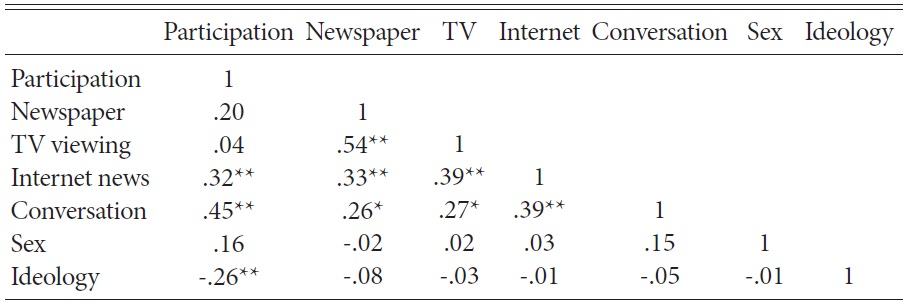

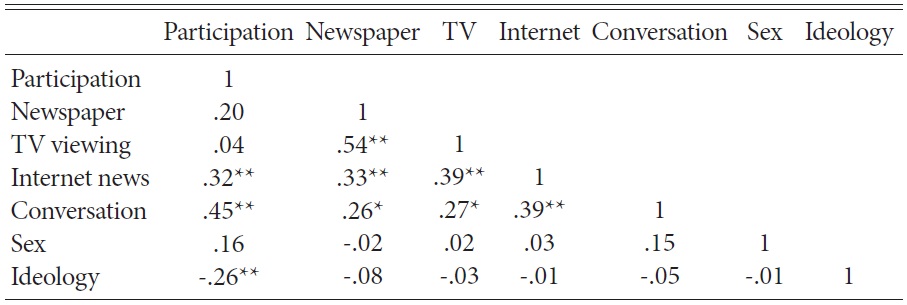

Bivariate Correlations between Political Participation, Media Use, Conversation, Sex, and Ideology

First, a bivariate correlation analysis was conducted to investigate the relationship between intention to participate in the protest and demographics, media use variables, and conversations with others. As shown in table 3, traditional media such as newspapers and television did not significantly influence the subjects’ attitude toward the protest. It was the Internet and interpersonal communication that resulted in the subjects’ criticism of the Korean government policy to import U.S. beef. The more frequently subjects used the Internet, the more positive they were toward the protest (r = .32, p < .01). Likewise, subjects who conversed more frequently with others regarding the issue were more likely to support the protest (r = .45, p < .01). As expected, political ideologies were a fundamental demographic factor influencing subjects’ attitude toward the protest; liberals supported and conservatives opposed the candlelight vigil. Interestingly, positive correlations were observed between each pair of the variables of media use and interpersonal communication. With respect to bivariate relationships between communication and media use variables, subjects who were newspaper readers were more likely to watch television news about the issue, to research the issue over the Internet, and to converse more frequently with others. Subjects who were more actively engaged in interpersonal communication were more likely to use the media, whether it be newspaper, television, or the Internet.

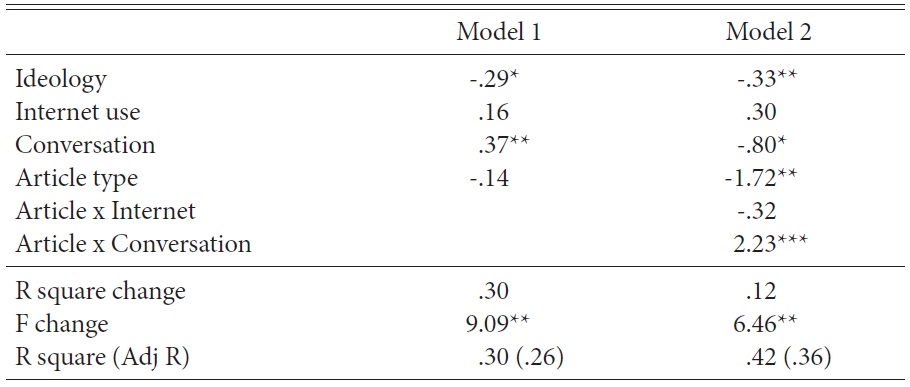

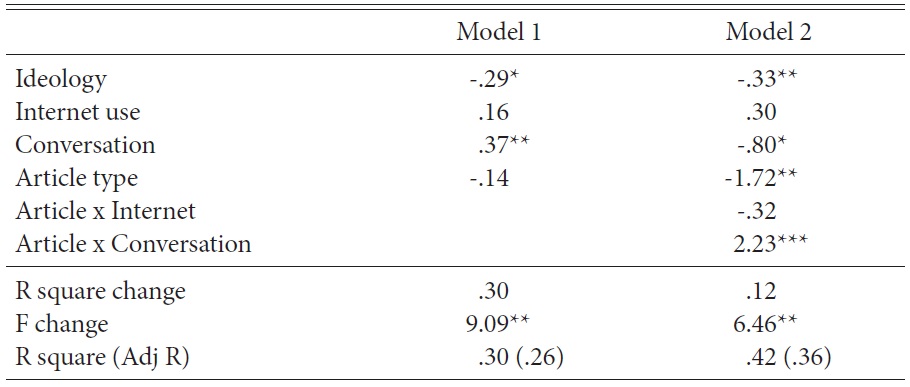

Next, with regard to the variables identified as influencing political participation, a hierarchical multiple regression analysis was employed to estimate the effects of the variance in each step of the models as well as the individual effects of predictor variables, including political ideology, Internet use, conversations with others, news article type, and two interaction terms (one for article type × Internet use, and the other for article type × conversation level). Key aspects of this analysis were two-fold, as follows: whether article type had a significant effect on determining political participation or not, and whether there was an interaction effect, through Internet use and conversation, on the dependent variable. Table 4 presents the results of this analysis.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis to Estimate the Impacts of Ideology, Internet Use, Conversation, Article Type (Experimental Treatment), and Interaction Terms of Article Type on Political Participation

Conversations with others exerted a significant effect on political participation (B = .37, p < .01). As delineated in the two‑step flow theory, mass media does not always have a direct effect on media users, but rather, opinion leaders who pay close attention to public matters play a vital role in disseminating such information throughout the public sphere (Katz and Lazarsfeld 1955; Lazarsfeld et al. 1944). Individuals who have more frequent opportunities to converse with fellow citizens are more likely to be politicized, more aware of the nuances of issues, and more likely to engage in political activities. Although the reverse relationship is also observed in reality (i.e., politicized individuals are likely to engage in political conversation), the result of this analysis confirms the political implications of daily-life conversation are not to be ignored.

Nevertheless, those subjects who engaged in more frequent conversation did not always have strong participatory intention, as appears in the results of Model 2 (with interaction terms), which reveal the negative effects of conversation on political participation (B = −.80, p < .05). The change from a positive effect to a negative effect indicates a statistically significant impact by interaction terms on the relationship between conversation and participation (Cohen et al. 2003). Furthermore, types of articles presented to subjects also showed significant interaction effects for the dependent variable. The effect of article type was not significant in Model 1 (B = −.14, p = .21); it was significant (B = −1.72, p < .01), however, when interaction terms were taken into account when regressing political attitudes on the predictor variables. The significant effect of the interaction term (article type × conversation: B = 2.23, p < .001) indicates that the effect of article type on political participation depends on the level of conversation with others.

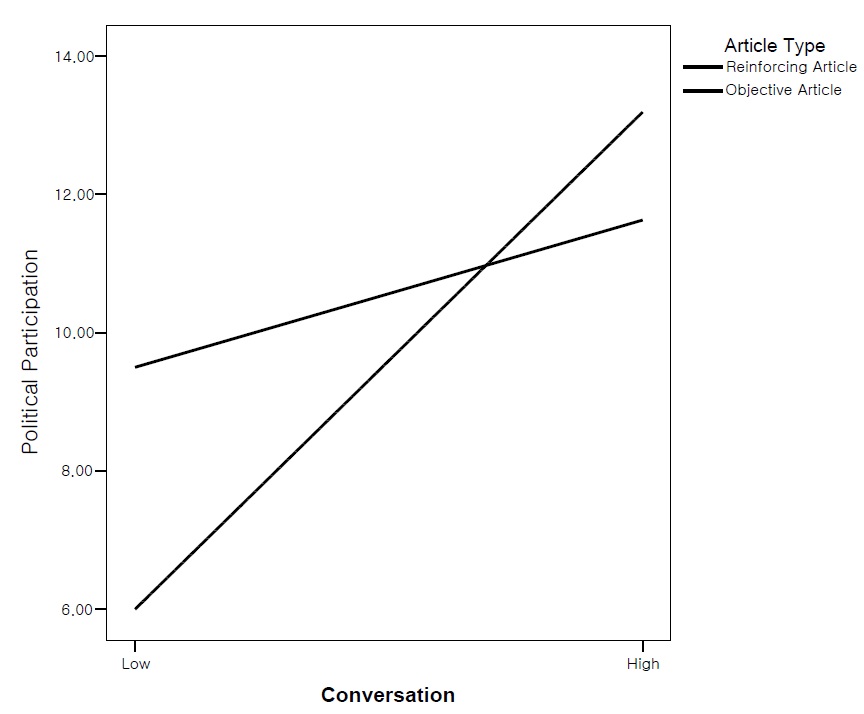

Figure 1 clearly shows an interaction between article type and level of conversation, the results of which indicate that there was crossover interaction between those two variables. Subjects who conversed less with others regarding the issue were more likely to be influenced by the reinforcing article to form participatory intention. Compared with those who read the objective article, subjects who were exposed to the article criticizing the government decision and explicitly encouraging participation in the candlelight vigil were, accordingly, more likely to lend support to protest movements opposing the policy. However, this phenomenon was only observed in the group of subjects having a low level of conversation. For those with a high level of conversation, the opposite was true; subjects who read the reinforcing article were inclined not to participate in the protest, whereas those with the objective article were more likely to voice their support for the candlelight vigil. This conflicting result may have been related to political knowledge. Subjects with a high level of conversation may have had a high level of knowledge about the issue and may have been oriented toward making a more informed decision (through observing unfolding events) (Eveland 2004; Eveland and Thomson 2006; Robinson and Levy 1986). These subjects were immune to the agitating voice delivered by the reinforcing article; instead, the objective news article, reporting only factual information about the situation, gave them a sense that participatory action would be legitimate.

The opposite was true for those with a low level of conversation. Since they were not sufficiently politically equipped to guide their judgments and actions by self-organized mature knowledge, the news article reinforcing political participation exerted profound persuasive impact on their behavioral intent.

The results show that the formation of opinions regarding the mad cow disease crisis was influenced by Internet use, conversations with others, and political ideologies, all of which showed significant bivariate correlations with the participatory intentions of subjects. It is notable that the traditional media did not affect subjects’ decisions regarding protest participation; this contradicts the widely held belief that the Korean mass media was the main culprit behind public resentment against the government and the U.S. The results of this study suggest that interpersonal communication strongly influenced public opinion on the issue and incited a favorable attitude toward protest movements. That is, the results indicate people are strongly affected by communication with others around them, including family members, friends, colleagues, and neighbors.

The second stage of the analysis demonstrates that article type showed significant interaction effects with the level of conversation. Table 2 shows that, although interpersonal communication produced an attitude favoring protest participation, this positive relationship depended on the type of news article presented to the subjects. For the group of subjects that had a lower level of conversation with others, news messages reinforcing the negative attitude toward U.S. beef imports and encouraging participation in the candlelight vigil led the subjects to decide in favor of protest participation. Subjects in the group exposed to the objective article tended to decide not to participate in the protest. In contrast, those with a higher level of conversation were more likely to be influenced by the objective article when forming an attitude favoring participation in the candlelight vigil. These subjects were not persuaded by the subjective article that presented an outraged opinion against the government decision and incited protest participation.

This study presents important implications for journalistic objectivity and public journalism. The notion of public journalism is embedded in the concept of a journalistic practice emphasizing the participant role of journalists and their civic engagement in community affairs. In pursuit of this goal, news articles produced by public journalists are likely to be biased about public issues, overcoming the mannerism of objective news reporting. Although public journalists blame journalistic objectivity for problems such as citizens’ ambivalent attitude and public cynicism, the results of this study suggest that this is not always the case. In situations where news consumers have wellestablished knowledge of important issues and converse frequently with fellow citizens, objective reporting actually promotes the legitimization of political actions, resulting in stronger participatory intentions on the part of the news consumer. An obvious limitation of journalistic objectivity is that a journalist must take on the role of a disengaged third person, but the willful ignorance of such a practice is not supposed to be the goal of the public journalist. Instead, objectivity needs to be distinguished from social detachment, and it is the latter rather than the former that a journalist needs to overcome. Although it is true that objectivity and social detachment overlap each other to a certain extent, a careful examination of the desirable journalistic role allows the two to be distinguished from each other.

Moreover, journalistic reinforcements are especially crucial for those members of society who receive media messages at the early stages of important issues. Since they are not exposed to frequent conversation at this stage, the impact of the news media will be greater than it will be during subsequent developments regarding the issue. This means it would be more effective for news articles to deliver specific views and encourage citizens to engage the issues, facilitating civic participation in political activities, at the early stages of an issue’s development. This temporal element of persuasiveness that depends on the type of news article sheds light on the theory of two-step flow of media communication, because its basic logic reveals the elements that contribute to the differences among members of the public with regard to opinion leadership (Katz and Lazarsfeld 1955; Lazarsfeld et al. 1944). Whatever the exact chain of causation is, the way in which newspaper readership and opinion leadership interact with each other reveals which one becomes more influential as public issues unfold. The role of opinion leaders would be more important during the period when the majority of people are still unaware of a given public issue. Along with prepared opinion leadership, a journalistic approach that reinforces civic engagement can become the driving force in promoting citizen politicization, such as participation in protests and other modes of political exertion. In this regard, future study on the temporal patterns of the impact of newspaper readership and opinion leadership is warranted.

Finally, it is necessary to discuss the role of the Internet in contemporary society, where the medium now represents a primary channel for conversation with fellow members of society. The soaring popularity of social media platforms providing networking-based communication in cyberspace, such as Facebook and Twitter, indicates that diverse modes of communication over the Net nurture public awareness on social matters and citizenship, helping individuals to exercise their rights and duties (Goodin and Niemeyer 2003; Kim et al. 1999; Kwak et al. 2005; Tewksbury 2003). The public sphere is not limited to the formal and official strata of citizens; it also includes spontaneous meetings in cafés, markets, streets, and even private homes (Eliasoph 1998). Although such spontaneous meetings tend to be less politicized, as Habermas (1989) once mentioned, informal talks between members of the public can have significant political implications. While moral justification for the candlelight vigil was not fully obtained, both online and offline meetings and conversations became an immense driving force for engaging lay citizens in public matters.

This study is the first attempt to argue that the effect of news reports on political participation is influenced by the public’s conversation with others. In the field of communication studies, journalism and interpersonal communication have been separate disciplines, with rare interaction between the two. Given that traditional mass media was blamed for being one of the primary causes instigating participation in the protest, this study is meaningful in that it provides a new insight into what truly motivates civic engagement in protest movements by addressing the public’s conversation as a determinant of news effects having significant influence on civic engagement.

Furthermore, the impact of news objectivity on civic participation has been empirically proven in this study. While there have been much criticism levied against news objectivity, little attempts have been made to scientifically examine whether objective press promotes or inhibits civic engagement.

Yet, it is necessary to mention that this study has its own limitation in generalizing its implications because only one specific political issue was examined. Moreover, the experimental design of having subjects exposed to only one of two types of articles might harm its internal validity, given that it is not certain which aspect of the articles has resulted in the variation. This warrants further studies of various political issues to be able to generalize the relationship between news objectivity and conversation in relation to political participation and how they play a role in democratic development.