The increasing cultural and ethnic diversity due to growing international migration coupled with the recent growing concern for human rights have motivated scholars to debate whether governments should officially recognize and support particular ethnic or cultural groups.1) In political science, liberalism and multiculturalism have been two main theories supporting the opposite side of the debate. Liberalism is favorable to the politics of indifference while multiculturalism is favorable to the politics of difference.

However, both liberals and multiculturalists have overlooked immigrants in the debate of minority rights. Liberals contend that if immigrant groups have equal political rights, such as citizenship, and socioeconomic rights based on citizenship, they will be assimilated into the majority society. Liberals also claim that culture or ethnicity does not matter as long as people with different culture and ethnicity get along well with each other in a society. Even multiculturalists, who advocate group-differentiated rights, assume that immigrant groups will be assimilated into the mainstream society. For example, Kymlicka maintains that immigrants come to a new country voluntarily and their cultures are not distinctive as much as those of national minority groups such as American Indians.2) Therefore, immigrant groups are divested of certain minority rights which national minority groups may demand.

In this article, I challenge both the liberalist underestimation of culture and Kymlickian dismissal of immigrants as minority groups by examining the assimilation pattern of Asian immigrants into the United States.3) The empirical evidence disputes both notions about Asian immigrants and their assimilation. Asian immigrants do not uproot themselves from their native culture. On the contrary, a large number of Asian immigrants speak their ethnic languages, choose to identify themselves with non-American identities, and most make friends with people sharing the same ethnicity. In addition, a large number of Asian immigrants feel discriminated against due to their ethnicity. These findings illustrate that Asian immigrants preserve their ethnic identity and cultural difference. Contrary to what liberals claim, citizenship and a higher level of socioeconomic status do not necessarily bolster Asian immigrants’ assimilation.

From this point onward, in the next section I review the claims made by liberals and multiculturalists about immigrants groups. In the third section, I reexamine Kymlicka’s argument on immigrants in greater detail. In the fourth, I empirically investigate the assimilation pattern of Asian immigrants. Finally, the article concludes with a summary of the argument and the findings.

1)Kwame Anthony Appiah, The Ethnics of Identity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005); Will Kymlicka, Multicultural Citizenship (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995); Charles Taylor, Multiculturalism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994); Iris Marion Young, Justice and the Politics of Difference (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990). 2)Will Kymlicka, op. cit. 3)In this article, Asian immigrants refer to people born in the United States who have an Asian background and who live in the United States now but were born in Asian countries.

Ⅱ. Liberalism and Multiculturalism

Fundamental values underlined by liberalism are individual freedom of choice and individual autonomy. Emphasizing these core values, liberals argue that a system of universal individual rights already accommodates cultural differences by allowing each person the freedom to associate with others in the pursuit of shared ethnic practices.4) Put differently, people in the liberal society will choose freely what culture they will join in the ‘cultural market place’. According to them, if people of minority groups are assimilated, that is their free choice in cultural market place.

Liberals further claim the politics of indifference; that is, the state should not promote or inhibit the maintenance of any particular culture. A liberal society should treat all individuals as equals, regardless of their particular ethnic, religious, racial or sexual identities.5) Instead, as liberals claim, the state should keep neutrality or benign neglect to cultural difference. If immigrants who acquire citizenship have equal political rights, such as voting, and decent income and education, they are enjoying equal political, economic, and educational rights to those of people in the mainstream. If immigrants have equal access to political and political rights, immigrants should be treated just as citizens, not as individuals having a particular cultural identity. That is, as long as immigrants enjoy equal political and economic rights, ethnicity and culture do not make any difference. Therefore, immigrants should not be treated differently. In sum, for liberals culture or identity does not play an important role in raising liberal citizens.

Such arguments on culture and immigrants imply that if a culture is valuable it will survive and attract new members to advocate in the cultural market place. Also, the majority culture is valuable because it successfully keeps its members and attracts new members. At the same time, these arguments suggest that a minority culture will be assimilated into the majority culture because of its weak viability. Thus cultural survival cannot be claimed as a right.6) The government should not give political recognition or support to a particular culture or ethnic group.

However, culture shapes individuals’ ideas and values which, in turn, affect their behavior. For example, culture affects whether a person considers freedom of choice as far more important than preservation of culture. In addition, liberals inaccurately understand how minority groups are assimilated. Assimilation often does not result from minority people’s free choice. The mainstream society forces assimilation by not giving them other cultural options.

Critiquing liberals’ idea of individualism, multiculturalists argue that distinctive identities, values, and traditions of different cultural groups should be recognized and protected.7) Taylor argues that the idea of difference-blind liberalism is untenable since dominant groups tend to entrench their hegemony by inculcating an image of inferiority into minority groups.8) He argues that due to the instilled inferior image, minority groups can suffer real damage. In other words, liberal neutrality is wrong because the mainstream refuses to coexist with minority cultures and because minority cultures and their dignity are ignored. As a response, Taylor argues that the society should recognize the equal value of different cultures. He does not specify how to recognize minority groups, but rightly points out that minority groups lack abilities to protect and develop their cultural life and that their cultural choices often do not result from their free will.

Similarly, Kymlicka contends that liberal ideas focusing on universal citizenship do not sufficiently protect minority cultures.9) He rightly argues that the society or the state should give group-differentiated rights to minority groups because they lack abilities to protect and develop their cultural life. However, in understanding immigrant groups, Kymlicka agrees with liberals. In the following section, I revisit his argument in detail.

4)Will Kymlicka, op. cit., p. 107. 5)Ibid.; Charles Taylor, op. cit., p. 4. 6)Chandran Kukathas, “Liberalism and Multiculturalism: The Politics of Indifference,” Political Theory 26-5 (October 1998), p. 694. 7)Ibid.; Will Kymlicka, op. cit.; Charles Taylor, op. cit., p. 64. 8)Charles Taylor, op. cit., p. 25 and p. 66. 9)Taylor critiques Kymlicka’s solution to accommodate difference of minority groups (see Charles Taylor’s note in op. cit., p. 41). However, I treat both on the same side in that both recognize the significance of minority groups’ culture and ethnicity.

Ⅲ. Kymlicka, Societal Culture, and Immigrant Groups

Kymlicka incorporates multiculturalism into the liberal framework. He emphasizes a liberal principle─“respect for individuals as autonomous choosers”─to defend cultural rights.10) However, Kymlicka contends that liberal ideals focusing on universal citizenship do not sufficiently protect minority cultures. For Kymlicka, a culture is an intergenerational community with certain degree of institutional completion, occupying a given territory and sharing a distinct language and history.11) Particularly, he views societal culture as a culture which liberal society should pursue. He defines societal culture as an institutionalized culture that provides its members with meaningful ways of life across the full range of human activities, encompassing both public and private spheres.12) Societal culture as national culture, according to him, is a culture which facilitates individual freedom and autonomy.

Kymlicka claims that the state should give differentiated rights to minority groups to preserve their culture because they are in unequal or disadvantaged positions with regard to preserving their culture. Group-differentiated rights provide options for minority group members to lead a meaningful life and thereby secure and promote liberal values, such as freedom of choice and autonomy. However, Kymlicka distinguishes national minority groups from ethnic or immigrant groups based on the viability of societal culture evaluated by the degree of institutional embodiment. He argues that only national minority groups are qualified to claim self-government rights13) since only they have societal culture. In Kymlicka’s understanding, immigrant groups have no societal culture as distinctive and institutionalized. Thus immigrants are not qualified to claim self-government rights. Instead, immigrant groups can claim only polyethnic rights which aim to assimilate them into the mainstream society.

He suggests three reasons why immigrants deserve only polyethnic rights. First, immigrants choose to voluntarily leave their country and culture.14) Second, immigrant groups are so lacking in institutional embodiment that they do not have societal culture. Lastly, immigrant groups are too dispersed, mixed, and assimilated to exercise self-government rights.15) Kymlicka, however, inaccurately understands immigrant groups. First, leaving a country is not synonymous with leaving a culture. Immigration occurs for various social, economic, or political reasons. For example, wage differentials, market failure, labor market segmentation, and globalization of the economy promote international migration.16) Also, immigrants keep their connections with their countries of origin.17) Besides, immigrants interested in facilitating capital accumulation acquire citizenship for a strictly utilitarian purpose. In short, immigrants do not migrate to other countries to uproot themselves from their culture.

Second, all immigrant groups are not more weakly institutionalized than national minority groups. Most immigrant groups show a high level of embodiment.18) They form and participate in various organizations to keep their cultural tradition, ethnicity and interest.19) They also teach their own cultural tradition and language to later generations in their own schools. For example, public schools in California provide Spanish and Chinese as official school languages.

Third, immigrant groups are neither dispersed nor assimilated as much as Kymlicka claims. One noticeable feature of the current immigration is its high degree of geographic concentration.20) California, New York, Texas, Illinois and Florida receive over 70 percent of the immigrants. About 40% of the nation’s Asian Americans live in California. In particular, half of all entering immigrants live in five urban cities: Los Angeles, New York, Chicago, Anaheim-Santa Ana, and Houston. Over 60% of Asian Americans today are new arrivals from Asia. The new arrivals lead their ethnic features more than later generations by continuously recharging their distinctive culture. As a result, immigrant groups are not ‘too’ assimilated into the mainstream.

To summarize, voluntary immigration is not synonymous with deserting a culture. In addition, all immigrant cultures are not weakly institutionalized. Immigrants are neither territorially dispersed. Continuous immigration strengthens the character of an ethnic group. When people migrate to a new country, they may leave their institutionalized culture such as schools or government within their home country. However, they bring their internalized culture such as how to perceive things and how to communicate with others. Such internalized culture as value, tradition, and practice affects how they act in the new society. Kymlicka mistakenly understands immigration as people’s leaving their culture because he defines culture as a set of embodied institutions to provide options to its members. However, not all meaningful cultural aspects are contained in an institutionalized form. My point is not that the US government or any government should give immigrant groups self-government rights; rather, lack of cultural distinctiveness and voluntarism are not convincing grounds for discriminatingly giving group rights.

In the next section, I examine if the possession of political rights and a higher degree of socioeconomic status automatically lead Asian immigrants to be more assimilated.

10)John Tomasi, “Kymlicka, Liberalism and Respect for Cultural Minorities,” Ethics 105-3 (April 1995), pp. 580-603. 11)Will Kymlicka, op. cit., p. 18. 12)Ibid., p. 76. 13)According to Kymlicka, there are a number of national minorities in the United States, including the American Indians, Puerto Ricans, the descendants of Mexicans living in the southwest when the United States annexed Texas, New Mexico and California after the Mexican War of 1846-1848, native Hawaiians, the Chamorro of Guan, and various other Pacific Islanders. 14)See also Michael Walzer, Politics and Passion: Toward a More Egalitarian Liberalism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004). 15)Will Kymlicka, op. cit., p. 100. 16)Douglas S. Massey, “The New Immigration and Ethnicity in the United States,” Population and Development Review 21-3 (September 1995), pp. 631-652; Pei-Te Lien, Margaret Conway, and Janelle Wong, The Politics of Asian Americans: Diversity & Community (New York: Routledge, 2004). 17)Leland T. Saito, Race and Politics: Asian Americans, Latinos and Whites in a Los Angeles Suburb (Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1998), p. 114; Nina Glick Schiller, Linda Basch, and Cristina Blanc Szanton, “Transnationalism: A New Analytic Framework for Understanding Migration,” Annals of the New York Academy of Science 645 (July 1992), pp. 1-24; Nina Glick Schiller, Nations Unbound: Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments and Deterritorialized Nation-state (Newark, NJ: Gordon and Breach, 1995). 18)Geoffrey Brahm Levey, “Equality, Autonomy and Cultural Rights,” Political Theory 25-2 (April 1997), pp. 215-248; Lelend Saito, op. cit.; Pei-Te Lien et al., op. cit. 19)James S. Lai et al., “Asian Pacific American Campaigns, Elections and Elected Officials,” Political Science and Politics 34-3 (September 2001), pp. 611-617; Douglas S. Massey, op. cit.; Leland Saito, op. cit. 20)Richard Alba and Victor Nee, “Rethinking Assimilation Theory for a New Era of Immigration,” International Migration Review 31-4 (Winter 1997), pp. 826-874; Pei-Te Lien et al., op. cit.

For the empirical analysis, I utilize the survey data

2. The Assimilation Dependent Variables and Hypotheses

I use two groups of dependent variables: cultural assimilation and social assimilation. Assimilation is a process which brings minority groups into the mainstream.21) Assimilation is divided into two steps.22) One is cultural assimilation, and the other is social assimilation. As a first step in the assimilation process, cultural assimilation is behavioral assimilation. Cultural assimilation is to express the major behavioral patterns of the receiving country by adopting its values and symbols such as language. Kymlicka also argues that meaningful societal cultural is embodied in institutionalized forms such as language and media.23) Thus I measure cultural assimilation with the following items: business language, home language, and exposure to American mass media.

Social assimilation is social and structural assimilation. As a final step in the assimilation process, social assimilation is achieved when immigrants are integrated into the formal and informal social structure of the receiving society. Social assimilation includes the formation of relationships with the receiving country’s members. It also includes the entry into organizations of the host society and the formation of new identification with the host country. At its extreme, social assimilation involves the complete obliteration of distinct identity. I measure social assimilation with the following items: close friendship with other ethnic/racial group members, belonging into ethnic/Asian organizations, and self-identification as American.24) Particularly, the entry into ethnic/Asian organizations and acceptance of American identity tap into whether Asian immigrants are assimilated into institutionalized forms of societal culture. I also measure discrimination experience as the last indicator of social assimilation. The perception of discrimination experience due to a distinct ethnic/national origin indicates the persistence of distinctive identity.

I set up four hypotheses based on the arguments made by liberals and Kymlicka. Liberals assume that equal political rights based on citizenship and stable socioeconomic status lead immigrant groups to be assimilated into a majority society. Kymlicka claims that culture and ethnicity of immigrants groups are not distinctive. I test whether improved political rights and socioeconomic status promote Asian immigrants to be ‘too’ assimilated into U.S. society to uproot themselves from their distinctive culture and ethnicity. The first and second hypotheses test whether Asian immigrants culturally uproot themselves from their own culture. Specifically, the first hypothesis tests if citizenship promotes cultural assimilation. To test this hypothesis, I examine all respondents regardless of citizenship status. The second hypothesis tests whether income and education bolster cultural assimilation of Asian immigrants with citizenship. Both the third and the fourth hypothesis test if Asian immigrants are socially assimilated. The third hypothesis tests how citizenship affects Asian immigrants’ social assimilation. The fourth hypothesis examines if the improved socioeconomic status promotes social assimilation of Asian immigrants with citizenship. I present the four hypotheses below.

I test these hypotheses, controlling for age and gender. Immigrants differ in their political and social behavior, depending on whether they are native-born or foreign born and whether they are mainly educated in the receiving country.25) I also control birthplace and place of education.26) Birthplace measures whether Asian immigrants were born in the United States. The place of education variable measures whether Asian immigrants are mainly educated in the United States.27) For the statistical method, I use binomial logit model and ordered logit model, depending on the number of the dependent variables.

3. Results and Interpretations

1) Cultural Assimilation

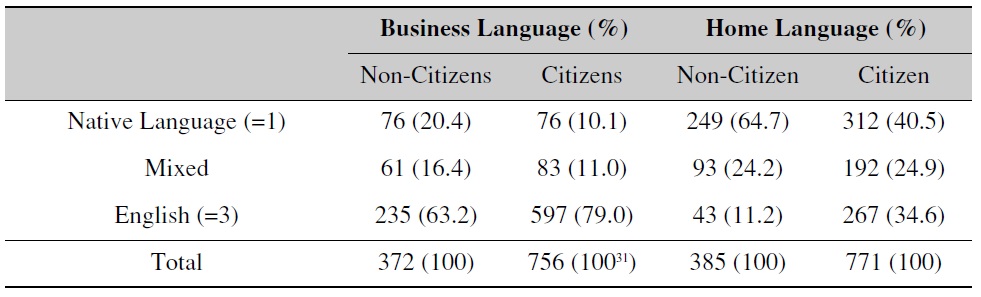

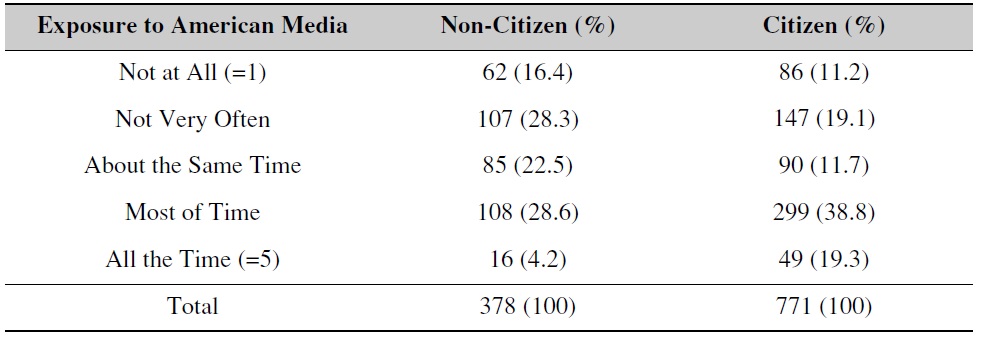

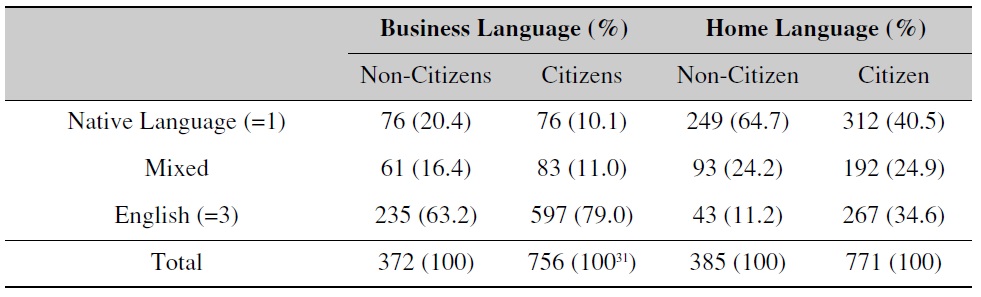

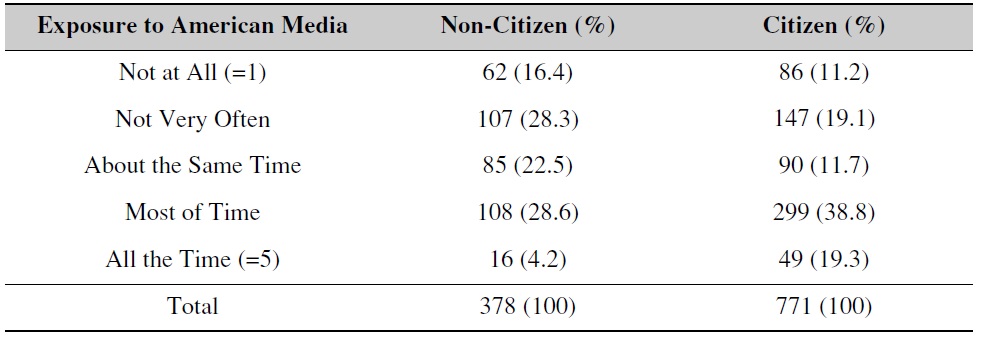

The first cultural assimilation variable is language assimilation. As shown in Table 1, almost 80% of Asian citizens speak English at work while less than 65% of non-citizens speak English at work.28) Citizenship holders also speak English at home (34.6%) more than non-citizens (11.2%).29) Similarly, as shown in Table 2 citizenship holders are more exposed to American media.30) These descriptive analyses indicate that Asian immigrants with citizenship show greater cultural assimilation than non-citizens.

[Table 1.] Asian Immigrants’ Business and Home Language

Asian Immigrants’ Business and Home Language

[Table 2.] Asian Immigrants’ Exposure to American Mass Media

Asian Immigrants’ Exposure to American Mass Media

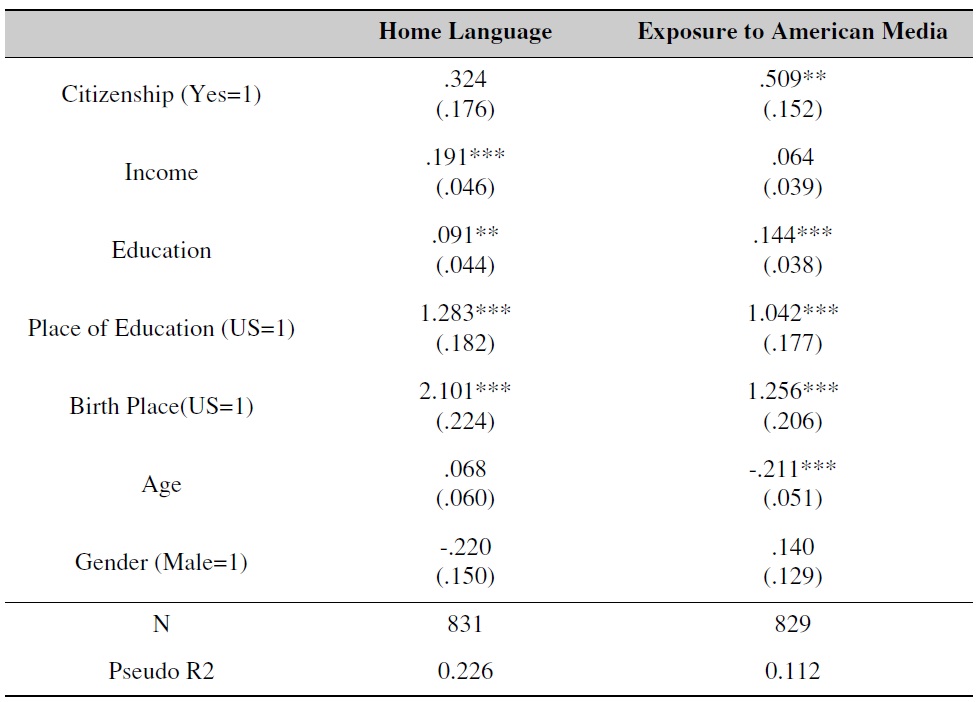

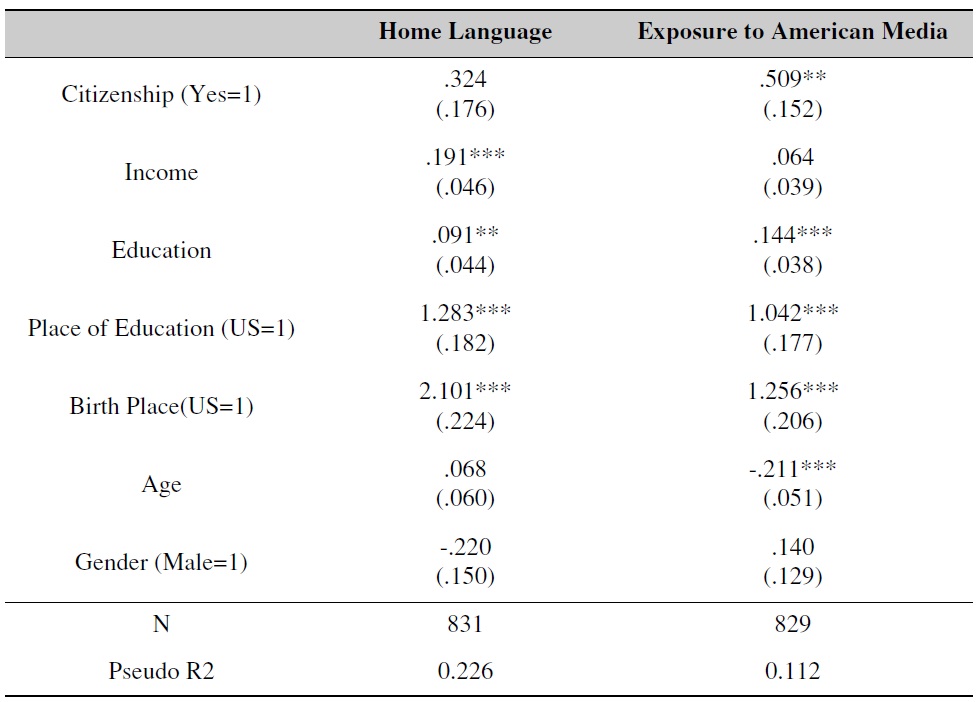

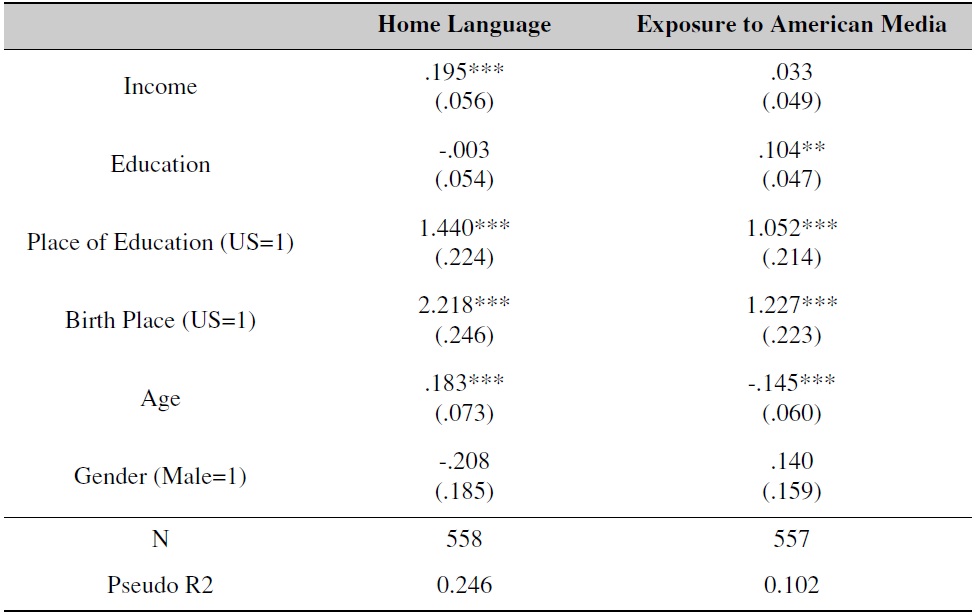

I examines if these findings are empirically supported when other conditions are equal. First, I investigate the assimilation patterns of Asian immigrants regardless of citizenship status. Table 3 presents empirical results on Asian immigrants’ cultural assimilation. Since business language is often chosen involuntarily, I use home language as a dependent variable to discuss language assimilation. As shown in Table 3, my evidence suggests that citizenship status is a significant factor for assimilation measured by media exposure while it has no impact on language assimilation. That is, unlike what liberals claim, being entitled to various political rights does not guarantee higher cultural assimilation among Asian immigrants.

[Table 3.] The Effect of Citizenship on Asian Immigrants’ Cultural Assimilation

The Effect of Citizenship on Asian Immigrants’ Cultural Assimilation

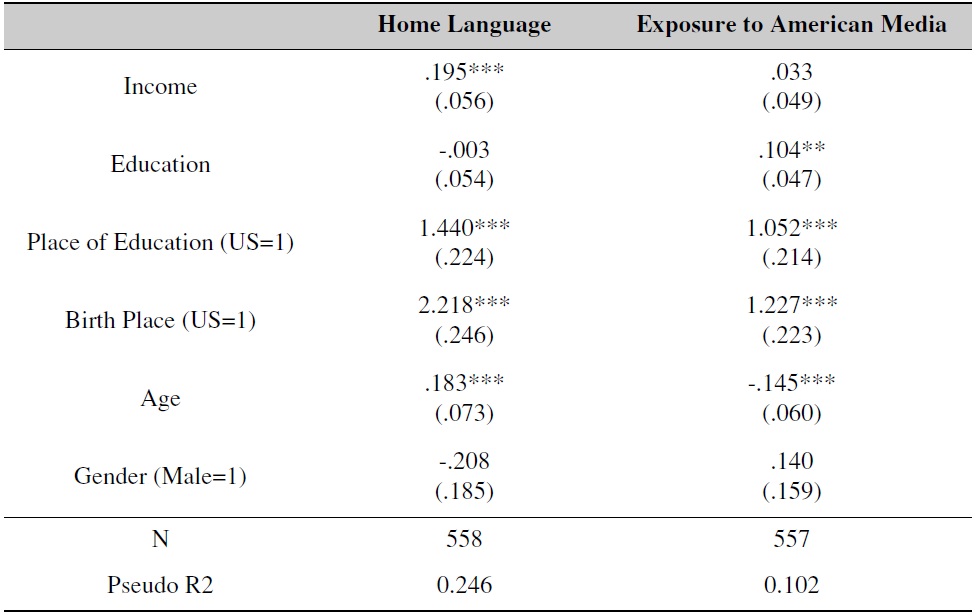

Instead, my findings indicate that Asian immigrants who study mainly in the United States and have a higher level of education are more culturally assimilated. These findings indicate that education plays an important role in Asian immigrants’ cultural assimilation. However, I find no impact of age on language assimilation. This finding suggests that Asian immigrants’ distinctive cultural features will not easily evaporate; young Asian immigrants, who are more likely to be born and mainly educated in the United States than the older Asians, keep their distinctive language tradition as much as the older generation. Liberals argue that the improved socioeconomic status promotes citizenship holders to be culturally assimilated. However, my empirical results indicate that the improved level of education and income does not necessarily lead Asian citizens to achieve greater cultural assimilation. As shown in Table 4, income significantly increases citizens’ language assimilation while education bolsters citizens’ exposure to American media. Instead, being educated in the United States is a strong predictor for Asian citizens’ assimilation, regardless of socioeconomic status. This finding suggests that the cultural assimilation of citizenship holders can occur more easily than liberals assume; Asian immigrants with citizenship are more likely to be culturally assimilated as long as they are educated in the United States. This finding also indicates that to be born in the United States bolsters Asian immigrants’ cultural assimilation. Two thirds of Asian immigrants are foreign born. The current Asian American communities are continuously recharged by new immigrants. Thus this finding implies that as long as new arrivals account for a large portion of the Asian immigrant community, their cultural traits would be distinguished from the society. Nevertheless, cultural assimilation is the first step in the process of assimilation. In the next part, I examine the social assimilation of Asian immigrants.

[Table 4.] Effect of Income and Education on Citizens’ Cultural Assimilation

Effect of Income and Education on Citizens’ Cultural Assimilation

2) Social Assimilation

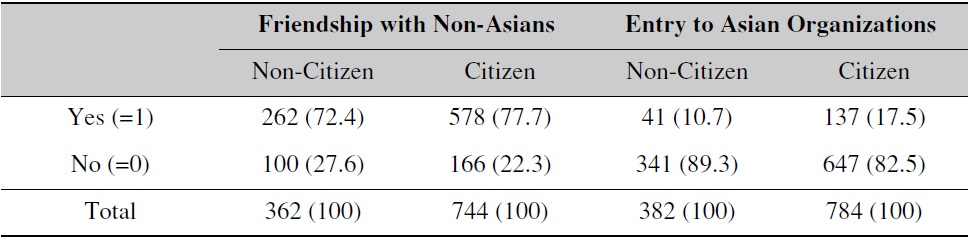

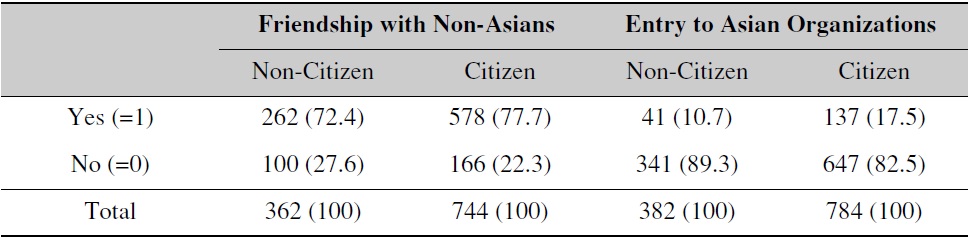

To examine Asian immigrants’ social assimilation, I chose four variables: close friendship with members of other ethnic/racial groups, belonging to ethnic/Asian organizations, self-identification as American, and discrimination experience.32) Before the empirical analysis, I examine social assimilation patterns among Asian immigrants. The descriptive analyses indicate that citizenship holders are not socially assimilated more than noncitizens. As shown in Table 5, citizenship holders do not make more friends with members of other ethnic/racial groups than non-citizens. In other words, even citizens tend to make friends with their coethnic members. Also, citizenship holders join their ethnic/Asian organizations that represent interests and viewpoints of their respective ethnic groups more than noncitizens: 17.5% of Asian immigrants with citizenship join their ethnic organizations while 10.7% of non-citizens join them. Citizens’ higher participation in ethnic/Asian organizations implies that Asian citizens try to preserve their ethnic interests more actively than non-citizens. It also indicates that Asian immigrants with citizenship have their own interests distinguished from those of the majority in the society. In short, their entry into those organizations indicates differentiation rather than assimilation.

[Table 5.] Close Friendship and Belonging to Ethnic/Asian Organizations

Close Friendship and Belonging to Ethnic/Asian Organizations

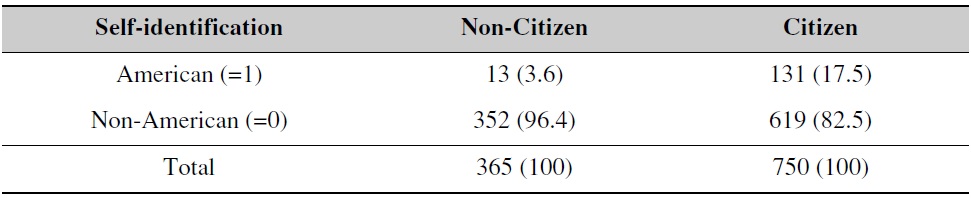

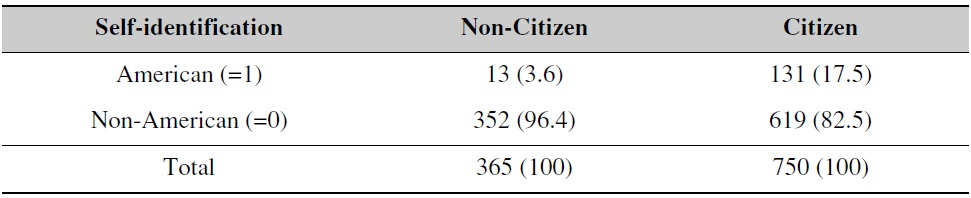

The identity transformation is considered as one of the final steps for social assimilation.33) As shown Table 6, citizenship holders identify themselves as Americans with greater percentage (3.6% to 17.5%). However, Only 17.5% of citizens identify themselves as American. That is, most of the Asian immigrants with citizenship are unwilling to identify themselves as American. This implies that Asian immigrants’ ethnic identity still persists even after they acquire citizenship.

[Table 6.] Self-identification as American

Self-identification as American

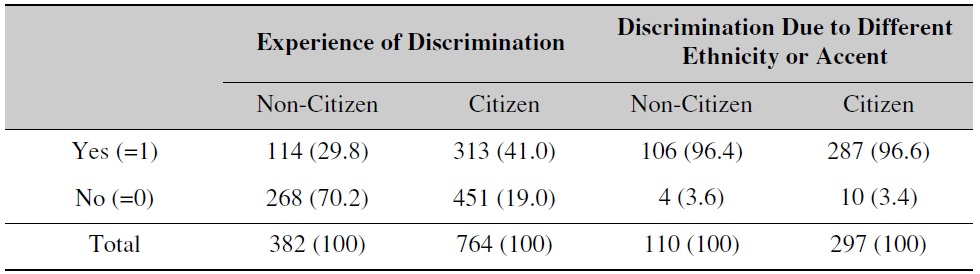

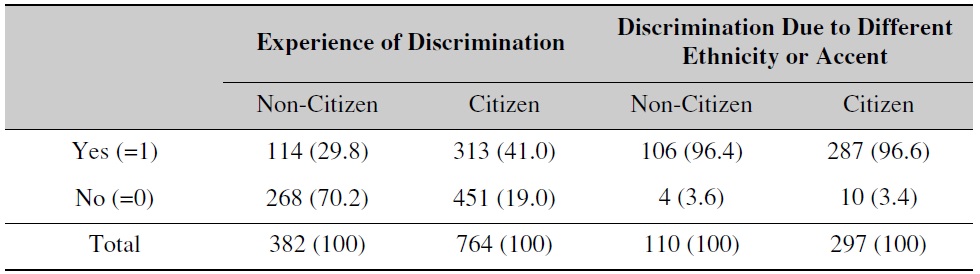

The ending of perception on discrimination due to ethnic differences is the final step in the social process.34) Asian immigrants with citizenship should feel less discrimination only due to their ethnicity or accent if they are successfully socially assimilated. However, as shown in Table 7, Asian Americans with citizenship experience more discrimination than non-citizen immigrants: 29.8% of non-citizens reported that they experienced discrimination while 41% of citizens reported discrimination experience. This finding indicates that citizenship holders are less socially assimilated into the mainstream society than non-citizen immigrants.

[Table 7.] Discrimination Experience

Discrimination Experience

Also, among 41% of citizens who reported discrimination experience, almost 97% of them reported that they were discriminated because they have different ethnicity and accent. This finding implies that ethnicity does persist and matter even for citizenship holders. Asian immigrants are fairly well aware of their distinctive ethnicity. This also suggests that Asian immigrants’ social assimilation may not be complete even though they have equal political rights and decent education and income.

Feeling discriminated against corresponds to feeling rejected by the mainstream society. In fact, the discrimination experience is both a cause and a result of unsuccessful assimilation. Discrimination experience prevents immigrants from being socially assimilated because it continuously reminds them of their distinctive ethnicity. That is, discrimination experience strengthens Asian immigrants’ distinctive identity even after they acquire citizenship. As a result, they cannot be fully assimilated into a new society.

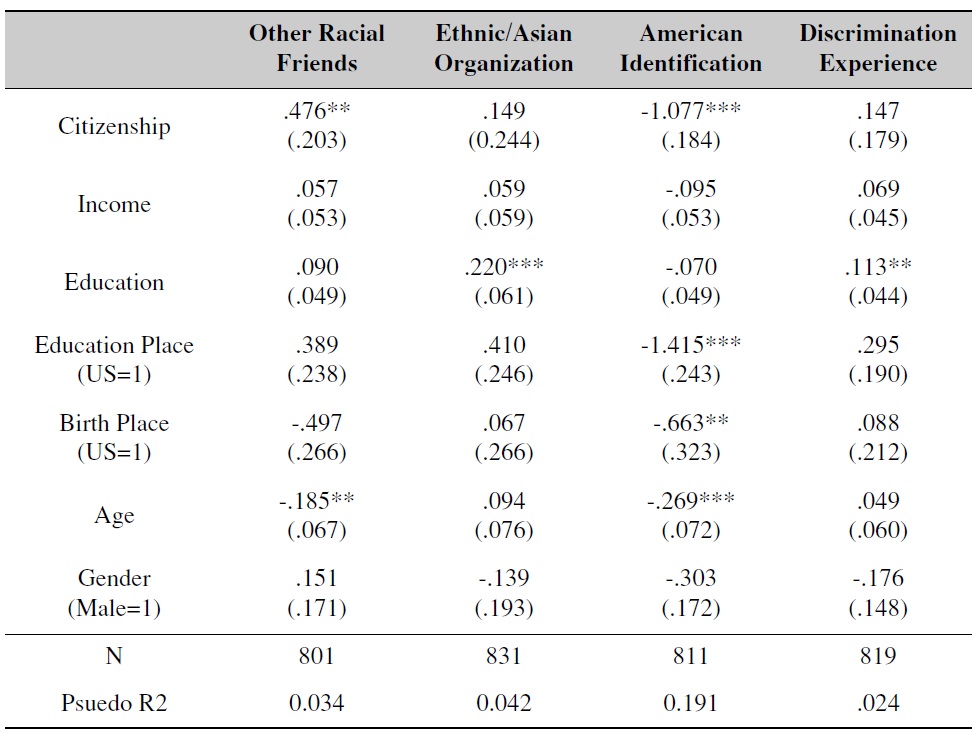

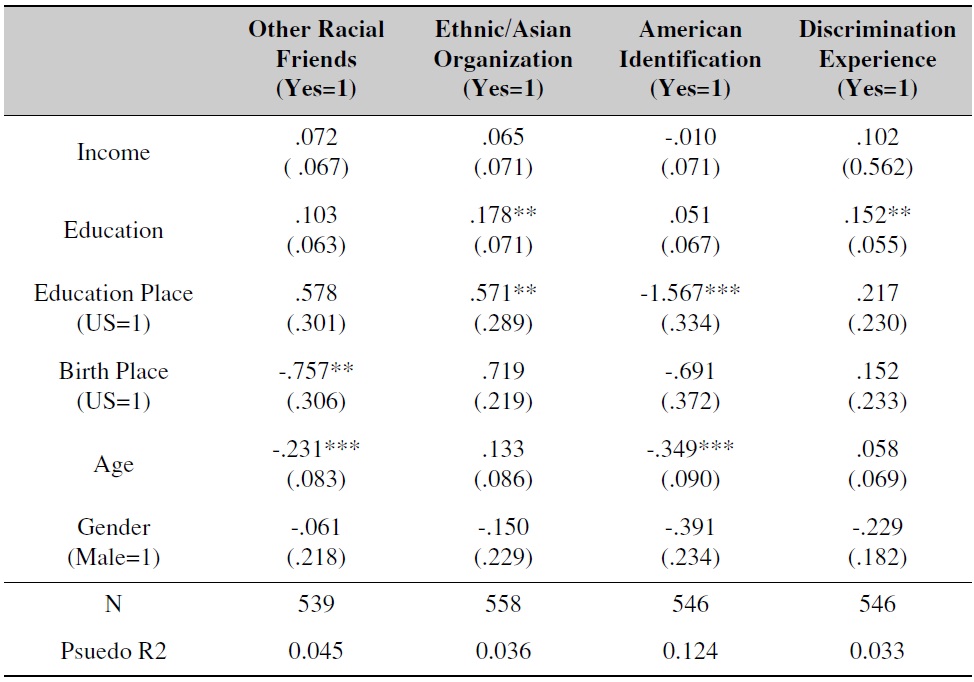

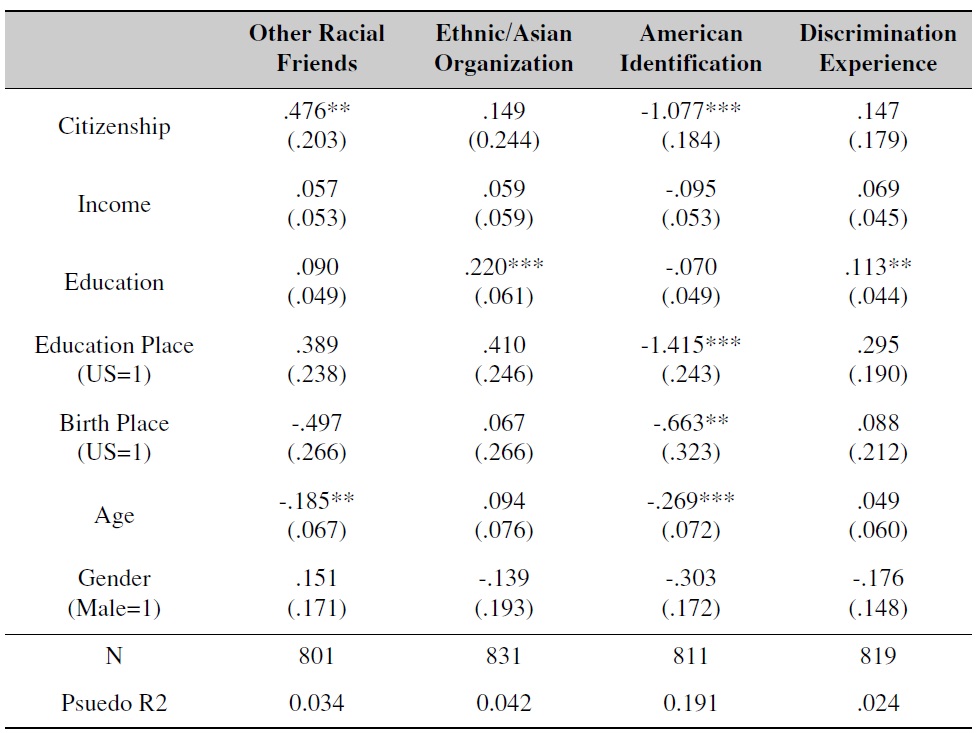

Table 8 summarizes empirical analyses on how citizenship status affects Asian immigrants’ social assimilation when other conditions are equal. The results indicate that citizenship promotes only Asian immigrants’ social assimilation in terms of making friends. Instead, the evidence in this article suggests that citizenship status significantly dampens Asian immigrants to hold American identity. In addition, citizenship status has no impact on Asian immigrants’ belonging to ethnic/Asian organizations and discrimination experience.

[Table 8.] Effect of Citizenship on Social Assimilation

Effect of Citizenship on Social Assimilation

Furthermore, I find no systematic effect of education and income on Asian Americans’ social assimilation. This finding implies that higher level of education and income does not help Asian immigrants to be more assimilated into the mainstream society. In sum, citizenship, a legal status which recognizes equal political and economic rights for Asian immigrants to those in the mainstream, does not necessarily lead Asian immigrants to be more socially assimilated.

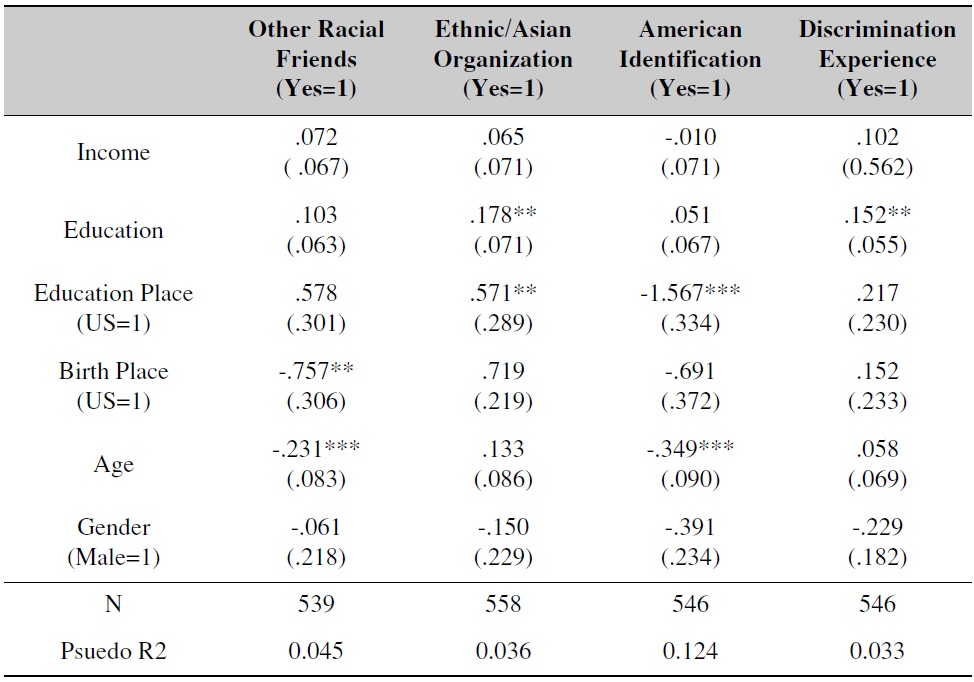

Table 9 present whether improved socioeconomic status promotes citizenship holders’ social assimilation. The empirical results show that higher education and greater income do not bolster citizens’ social assimilation. In contrast, education encourages Asian immigrants with citizenship to feel their distinctive identity. Citizenship holders with higher education are more likely to join their ethnic organizations and to experience discrimination. Also, being educated in the United States also does not help them. They are more likely to join their ethnic organizations and to experience discrimination. Being educated in the United States also does not help them to be socially assimilated. Rather, it bolsters citizenship holders to join ethnic/Asian organizations and feel discriminated. In sum, both the third and the fourth hypothesis are not empirically supported.

[Table 9.] Effect of Income and Education on Citizens’ Social Assimilation

Effect of Income and Education on Citizens’ Social Assimilation

21)Richard Alba and Victor Nee, op. cit.; Brewton Berry, Race Relations (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1951); Robert E. Park and Ernest W. Burgess, Introduction to the Science of Sociology (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1921). 22)Milton M. Gordon, Assimilation in American Life: the Role of Race, Religion and National Origins (New York: Oxford University Press, 1964); Mirra Rosenthal and Charles Auerbach, “Cultural and Social Assimilation of Israeli Immigrants in the United States,” International Migration Review 26-3 (Autumn 1992), pp. 982-991; Ethna O’Flannery, “Social and Cultural Assimilation,” American Catholic Sociological Review 22 (1961), pp. 195-206. 23)Will Kymlicka, op. cit. 24)I use belonging into ethnic/Asian organizations as an alternative variable for the entry into organizations of the host society. 25)Pie-Te Lien et al., op. cit. 26)The exact question wording for the birthplace variable is “Were you born in Asia?” When respondents were born in the United States, they are given ‘1’ while they are given ‘0’ when they were born in Asia. The exact question wording for the place of education is “Were you educated mainly in the United States?” When respondents are mainly educated in the United States, they are given “1” and otherwise “0”. 27)Immigrants’ degree of assimilation can be affected by their length of stay in the United States. However, the PNAAS asks the question on the length of stay only to those who live in the United States on a permanent basis. That is, the question covers those who have citizenship or permanent residence status. Also, some citizenship holders or permanent residents do not live in the United States on a permanent basis for various reasons. Moreover, the length of stay is multi-correlated to the birthplace variable. 28)The exact question wording is “What language do you usually use to conduct personal business and financial transactions?” (Choices: English/Something else/Mixed between English and other). 29)The exact question wording is “What language do you usually speak, when at home with family? (Choices: English/Something else/ Mixed between English and other) When respondents answer “English” for the question, they are coded as three while they are given one when they answer “something else.” 30)The exact question wording is “Compared to your usage of the English media, how often do you use [R’s Ethnic Group’s] language media as a source of entertainment, news and information? (Choices: all of the time/ Most of the time/ About the same time/ Not very often/ Not at all) When respondents answer “Not at all,” they are coded as five while they are given one when they answer “All the time.” 31)Because of rounding, the combined percent may be very slightly over 100%. Yet, the exceeding percent will not be more than 1%. 32)Exact wording of these variables is as follows: i) “Thinking for a moment of blacks, whites, Latinos and other Asians, do you yourself know any person who belong to these groups whom you consider a close personal friend or not? If yes, what ethnic groups do you belong to?” (Choices: No/Yes, White/Yes, Black/Yes, Latino/Yes, other Asian/Yes, Other). When respondents answer they have friends from other ethnic/racial groups, they are coded “1” and otherwise zero. ii) “Do you belong to any organization or take part in any activities that represent the interests and viewpoints of [R’s Ethnic Group] or other Asians in America?” (Choices: Yes/No). When respondents answer “yes”, they are coded “1” and otherwise zero. iii) “In general, do you think of yourself as an American, an Asian American, an Asian, a [Respondent’s ethnic group] American, or a [Respondent’s ethnic group]?” I take a value of “1” when respondents identify themselves as Americans while I take a value of “1” for other identifiers. iv) “Have you ever personally experienced discrimination in the United States?” (Choice: Yes/No). [If yes] in your opinion was it because of your a. ethnic background/ b. accent, regardless of whether or not you have an accent. (Choices: Yes/No) I take a value of “1” when respondents reported they experienced due to either ethnic background or accent and otherwise zero. 33)Samuel N. Eisenstadt, The Absorption of Immigrants (Glencoe, IL: The Free Press, 1955); Ethna O’Flannery, op. cit.; Pie-Te Lien et al., op. cit. 34)Milton Gordon op. cit.; Mirra Rosenthal and Charles Auerbach, op. cit.

The empirical evidence presented in this study suggests that citizenship, higher education, and greater income do not necessarily assimilate Asian immigrants into the American society. Over 65% of Asian immigrants with citizenship still speak their language at home. As well, citizenship holders participate more in their ethnic/Asian organizations to represent their interests and viewpoints. Although citizenship status encourages Asian immigrants to make friends with other racial group members, most citizenship holders make friends with people sharing the same ethnicity. In addition, a large number of Asian immigrants feel discriminated against due to their ethnicity, and identify themselves as non-Americans after they acquire citizenship. These findings illustrate that Asian immigrants preserve their ethnic identity and cultural difference even after they are guaranteed equal political rights. This evidence also indicates that improved socioeconomic status neither necessarily weakens Asian immigrants’ ethnic and cultural identity nor promotes their assimilation.

We may view the process of European Assimilation as a model for the incorporation of Asian immigrants into the U.S. society. However, Europeans are successfully assimilated for several different reasons. First, the decedents of earlier European immigrants could eventually assimilate “because their European origins made them culturally and racially similar to American ethnic core groups from British and some northern and western European countries.”35) Second, the economic boom between the 1940s and 1960s helped European immigrants to become smoothly ‘white ethnics’.36) Third, the new immigrants from Europe have dramatically decreased since the late 1960s. As a result, the culture of European immigrant groups has not been strengthened by new arrivals.

For Asian immigrants, assimilation is harder because they have nonEuropean origins and languages. Moreover, they are instantly distinguished by physical appearance. Asian immigrants cannot hide their origins even after many generations. As a result, Asian immigrants will persistently feel their differences either ethnically or racially. In addition, unlike European immigrants of the past, the number of Asian immigrants is expected to increase steadily with new arrivals from Asian countries. The culture of immigrants is usually influenced the most by the first generation of immigrants. The increasing number of new arrivals continues to supply the culture of Asian immigrants. As a result, their distinctive cultures will persist. Meanwhile, equal political rights and improved socioeconomic status play a limited role in assimilating Asian immigrants into the mainstream society.

In conclusion, Asian immigrants’ ethnicity and culture persist and matter. They do not uproot themselves from their own cultures. Kymlicka and liberals claim that less institutionalized cultures should be assimilated into the dominant culture to promote the homogenization of different cultures. However, the findings of this study directly conflict with their principal claim that society should pursue pluralism.

35)Richard Alba and Victor Nee, op. cit., p. 845. 36)Bruce Burgett and Glenn Hendler, Keywords for American Cultural Studies (New York: New York University Press, 2007).