Since the late 1990s, Korean popular music has achieved an audience beyond Korea, becoming a leading part of the growing phenomenon of inter-Asian popular music (Shin 2009: 472). Musically indebted to hip-hop and Western pop, Korean popular music is generally performed by all-male or all-female groups. Although scholars have discussed the global rise in “girl power” in the field of popular music using examples such as Madonna, the Spice Girls, and Faye Wong (Fung and Curtin 2002, Dibben 1999, Lloyd 1994, McClary 2002), few can argue for “girl power” in Korean popular music (hereafter K-pop). One reason is that K-pop is almost entirely a manufactured commodity: the stars, called “idols,” are scouted, trained, and assigned to a group with a carefully pre-prepared image under the tutelage of K-pop’s major entertainment companies. At the helm of each company, CEOs oversee the production of K-pop idols in a way strikingly similar to preparing other commodities for the market.3

With few exceptions, K-pop songs, choreography and costumes are chosen by an artist’s management agency. These agencies in fact control many aspects of performers’ lives. They provide housing in dormitories, determine their artists’ diets, and forbid dating. As a reward for hard work, they dole out cell phone privileges.4 Therefore, analysis of song lyrics, choreography, and costume choices reveal less about the performers’ artistry and more about the agencies, and how they understand the popular culture industry. Yet there is much to be learned from analyzing popular music performance. In this article through a specific focus on the presentation and framing of televised performances we can gain a new window of understanding on sexual objectification in K-pop.

In this study, I analyze performances recorded live in front of audiences then aired on the TV shows Music Core (Munhwa Broadcasting Company or MBC) and Inkigayo (Seoul Broadcasting System or SBS).5 My attention focuses on choices made by the television stations specifically the emcees, stage and video production crews. By analyzing specific televised performances, I reflect on how these music programs perpetuate sexual objectification despite a law meant to restrict broadcast in order to protect juveniles. I have found that despite calls from large swathes of the Korean public for less blatant expression of sexuality in Kpop performance, television programs actively contribute to sexual objectification of the performers.

3Although K-pop is largely controlled by management companies, one unique thing about K-pop is the power fans wield. The fans of K-pop have affective power—power to sometimes change decisions and actions—both vis-à-vis the artists and their management companies (c.f. Gitzen 2013), although the degree of fan influence is difficult to quantify. 4For more details on agency control of idols, there are many blog and newspaper articles to draw on such as this article in Seoul Beats from May, 2012 by Nabeela: http://seoulbeats.com /2012/05/the-dogma-behind-the-dating-ban/. Accessed on 02/20/2013. This story is really interesting, partially because it shows the rare case of a group trying to resist the idol system: http://noisey.vice.com/blog/great-white-hope-how-bradley-ray-moore-accidentally-conquered-Kpop. Accessed on 10/6/2013. Sources in Korean are even more plentiful; see this article by Yonhap News published by the Hanguk Ilbo newspaper in January 2013: http://news. hankooki.com/ lpage/culture/201301/h20130122093623111780.htm. Accessed on 02/20/2013. 5Other similar shows include KBS’s Music Bank and M! Countdown by Mnet. I used Inkigayo and Music Core only to provide a measure of focus.

II. MUSIC PERFORMANCE AND THE VIEWER

For decades the impact of music on morality has been argued in popular media and public discourse. Many members of my generation grew up cursing Tipper Gore and her Parents Music Resource Center for censorship of music. The PMRC attacked extreme lyrics, and anti-social and even violent behavior was blamed on the musical preferences of once—“good” kids. An early example of this is found in the case of Wayne Lo, a student gunman who killed and wounded several students and a professor in 1992 on the campus of Bard College at Simon’s Rock. The national press explained that “when his music changed, Wayne Lo changed,”6 strongly implying that Lo’s taste for hardcore led him to kill.7 By similar reasoning, young women are thought to become sexually active at earlier ages in imitation of mediatized depictions of sexuality, leading to calls for regulations and restrictions. Although music theorists such as Simon Frith theorize the role of music in identity construction (Frith 1996: 275), responses to music vary widely. In other words, although media presents certain interpretations and practices, there are multiple reactions to media. As an extreme example, widespread international uploads of group dances and parodies of Psy’s “Gangnam Style” demonstrate how audiences can place themselves in a cultural narrative in ways presumably unanticipated, if welcomed, by Psy and his management company.

If responses to music vary so widely, is there a way to generalize how musical performance impacts the viewer? Scholars of culture and performance have proposed various approaches that reflect the personal volition of the consumer while acknowledging the power of media. Victoria Alexander speaks of the impact of popular culture on the consumer in terms of “shaping approaches” (2003: 41). Shaping theories argue that works of art are impregnated (by the creator) with ideas that, when consumed, give birth to certain perceptions and actions by the consumers. Various scholars have addressed how women are depicted in music through visual appearance, demonstrations of expert ability (writing songs, playing instruments) and song lyrics. The backstage processes (Goffman 1990) have been studied by Lucy Green (1997), who examines the role of gender in music education, and front and backstage has been addressed by Susan McClary (2002), who questions the processes that have led to the construction of staged representations of femininity. Social conceptions of femininity and masculinity are constantly being constructed based on positive, negative, and subconscious reactions to the environment. Most of East Asia remains governed by entrenched gender roles that include conservative ideas about exposing skin, although ideas about what to cover varies in the region. It is unsurprising, then, that K-pop’s revealing clothing and suggestive dance moves can stir debate.

In the Republic of Korea, and in areas influenced by K-pop, fan consumption of K-pop idols’ videos and live performances proves to be a powerful force for instilling feminine ideals and constructing femininity. In Korea, how popular music is displayed (and discussions of music and personalities in music, whether through the media, blogs, or websites for distributing media) provides a dominant example of how “attractive” women behave, while teaching everyone what type of woman is attractive. This is important because girls and women are pressured to “manufacture themselves into objects of desirability” according to the example set by popular culture (Epstein and Joo 2012, also Elfving-Hwang 2013; Holliday and Elfving-Hwang 2012; Sohn 2009). Epstein and Joo connect the dress and actions of these stars with the growth in plastic surgery and changing fashions in Korea and beyond.8 Aljosa Puzar calls this fantasy narrative dollification, because the standard of comparison for performers seems to be not living women but dolls:

Dollification is connected to the emergence and popularity of the cutesy behavior called

Girlie-girl behavior is not only an issue in Korea; it is also apparent in popular music in the West, which portrays women as “simultaneously submissive, innocent and childlike, yet sexually available” (Dibben 1999: 336). K-pop stars are also controlled by their own fame. Epstein and Joo discuss how fans and media become a panoptic presence in the lives of the stars. The performers are selling a “fantasy narrative” in addition to their music.10 This fantasy gives fans a feeling of ownership of the stars; to preserve their product’s value, most CEOs, at least initially, restrict idols’ freedoms to prevent them from engaging in normal faux pas or celebrity-specific shenanigans.11 Because performances of K-pop idols are so meticulously choreographed, they are simultaneously active (dancing) and passive (acting according to an imposed routine).

Although some scholars have claimed that consumers can find a measure of freedom in the genre,12 the artists in 2013 are not rebellious trail-blazers like Kpop forerunner Seo Taiji.13 Despite the occasional release of songs that seem to empower women, the calculated crafting of image, song, costume, and choreography under constantly involved male CEOs undermines the empowered images of a few select K-pop groups.14 Korean women have been, generally speaking, socialized to act within clearly defined traditional gender roles when compared with women in the post-feminist-revolution US. It is clear that a genuine message of female empowerment as an economically profitable approach in production of popular music is not a current strategy for Korean popular music management companies. When challenged, management companies fall back on the predictable argument that they

Stephen Epstein, publishing in 2010, found that Koreans characterized Korean performances and performers as “wholesome” in comparison with the Japanese and suggested that Koreans may not want to relinquish that sense of moral superiority due to overly sexualized performances, yet since Epstein conducted his research it seems that wholesomeness is gone. Today behavior that K-pop models for young women is troubling on various fronts. Tweens and teens copy the increasingly sexual dance moves in K-pop videos—in fact, the participatory nature of dancing K-pop choreography is one of the reasons that K-pop is said to have become so popular across international markets. Idolizing K-pop stars, teens aspire to the traits most focused on in media coverage of the genre, namely physical beauty. The proliferation of increasingly blatant sexually objectifying performances may be directly tied to a perception that to compete with highly sexual and globally popular American pop, Korean popular music has to become more sexual than even two or three years ago.

Writing about the US in

6This same statement was used repeatedly by the media, including in a New York Times article by Anthony DePalma from December 28th, 1992. Available on line at http://www.nytimes.com/1992/12/28/us/questions-outweigh-answers-in-shooting-spree-at-college.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm. Accessed 2/27/2013. 7Hardcore is a punk rock music genre with faster and more aggressive songs than regular punk rock. One of the stereotypical punk rock groups, Sick of It All, was even depicted on the shirt Lo wore during the shootings. 8In this age of globally circulating media, how Korean idols are packaged is a potent issue outside of Korea. Daniel Black explains, “The stories of Chinese fans wanting surgery to look like Korean drama stars, and the erotic investment in pop stars and actors more generally, make it clear that the export of such visual media texts is strongly tied to bodily specificity, as is the circulation of bodily styles of media performance such as the singing and dancing of pop stars, and the appropriation of foreign fashion influences” (2010: 16.6). For more on the prevalence of plastic surgery in Korea, I recommend Holliday and Elfving-Hwang’s “Gender, Globalization and Aesthetic Surgery in South Korea” (2012). 9G.NA is 5’6” and just over 100 pounds. 10From an article in the Japan Times by Ian Martin, published February 1st, 2013. Available at http://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2013/02/01/music/akb48-members-penance-shows-flawsin-idol-culture/#.UQ63PSdpeh5. Accessed 2/03/2013. 11In the same article cited in the previous footnote, Martin discusses a rare scandal with an idol group—in this case the actions of one member of Japanese group AKB48. “The central problem of groups such as AKB48 is the defense that by dating, idols are ruining fans’ fantasies. This is key to understanding not just AKB48 and their sister groups, but pretty much all idol culture. The groups are not just selling music, they are selling a fantasy narrative. It’s one that everyone knows is fake, which is why it is imperative that fans’ suspension of disbelief be maintained at all costs— with severe punishments for those who step out of line.” 12Lee claims in her abstract that “K-pop provides discursive space for South Korean youth to assert their self-identity, to create new meanings, to challenge dominant representations of authority, to resist mainstream norms and values, and to reject older generations’ conservatism” (2004: 429). 13Seo Taiji is generally considered the earliest “modern” K-pop artist for his performance style combining rap and hip-hop with choreographed dance and balladic verses. For more information on Seo and his impact on Korean popular music, see relevant chapters in Korean Pop Music: Riding the Wave, edited by Keith Howard (2006). 14For example, Mark at Seoul Beats writes in an article from November 9 th , 2012: “The need for 2NE1 and miss A to balance their fierce personalities with softer ones speaks of the market in which they cater to. In order to branch out and connect with a larger fan base, they must occasionally differentiate their style to appeal to those who prefer a woman’s gentler side. This shows that they’re manufactured primarily to make money, although empowering women may be a secondary objective.” The article is available at http://seoulbeats.com/2012/11/manufacturedgirl-power-female-empowerment-in-a-male-powered-industry/. Accessed on 3/20/2013.

III. REGULATIONS, CULTURAL POLICY, AND K-POP

As K-pop has grown in national and international importance, the government in the Republic of Korea has sought to both mitigate the perceived influence of idol-driven culture on Korean youth and protect K-pop as a soft-power resource for the promotion of Korea overseas. The industry has attempted to get ahead of government regulations by self-regulating—in 2009 the Corea Entertainment Management Association (CEMA) developed a licensing exam and standard contract for use by all entertainment groups, but this standard contract has not been effective. Unscrupulous agents continue to take advantage of young trainees. For example, in early 2013 it came to light that the CEO of Open World Entertainment had sexually harassed his female trainees and facilitated their harassment by both his friends and male trainees.15 A report on sexualization of teens in Korea, released in English by Human Rights Korea on December 3rd, 2012 reveals the ongoing struggles with this issue.16 The report cites the response of the Korean Communications Commission to a “scandalous” 2011 performance by Hyuna (a solo performer who is also part of the group 4 Minute).17 The report follows: “Recently, there was a dispute regarding the choreography and stage clothing of girl groups Secret and KARA that their performance was too sensual and embarrassing.” The report continues on to state that in June 2012, the Ministry of Public Administration and Security formed the “Federation of Protecting Cyber World” cooperatively with civic groups. The federation uses the volunteer hours of concerned citizens to report potentially harmful content. In September 2012 the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, alerted by the federation, called for the censorship of thirteen advertisements, with hefty fines to be levied for inaction.

>

K-pop as a Korean Ambassador?

Complexity in regulating K-pop is introduced by the government’s appropriation of K-pop as an appealing international ambassador of Korea. The bodies and even sexuality of young K-pop stars are patriotically enlisted in this arena of international competition for the government, “objectified as normative commodities under corporate governmentality” (Kim YR 2011: 342). This is not unlike the ways that struggles of Korean athletes have been appropriated to “fight” for the nation (Joo 2012). New president Park Geunhye (Pak Kŭnhye) has already championed the “creative economy” (

Although Psy became a worldwide sensation with the 2012 hit “Gangnam Style,” K-pop is still relatively unknown outside East and Southeast Asia. In that region, however, K-pop and other aspects of Korean popular culture including TV dramas and movies are highly lucrative and extremely successful. The government’s interest in using K-pop for soft power has had to be tempered by government officials’ desire to avoid being associated with the negative aspects of the K-pop industry. Namely, the government has moved to prevent scandals through legislation as well as respond to domestic concern about the influence of idol culture on youth; even hints of bullying within K-pop draw the government’s attention.19 Exploitation of Korean pop performers by or with the complicity of their management companies is a well-known and often discussed issue, if the government associates Korea with K-pop on an international front, then the government may become complicit in exploitation. If the government maintains some distance from K-pop, much of the exploitation will continue to be characterized as part of the price for fame and most citizens will place responsibility on management agencies and parents, not the government.

The best-known accusations of exploitation so far have revolved around contract disputes between management companies and artists from major groups.20 Although fans frequently take sides in disputes between idols and management (Gitzen 2013), few question the idol-making machinery until a beloved star encounters difficulties.21 Sexual exploitation of stars, unlike contract disputes, receives much less notice, leading some columnists to claim that K-pop fans are “largely desensitized to issues involving the inappropriate sexualization of the female form.”22Fan engagement, and demand for more respectful nonobjectifying treatment of the performers could bring about change if fans directed their energies in that way.

The presentation of Korean celebrities is increasingly influenced by the ways that international audiences view and consume Korean popular music products and groups—Epstein and Joo’s “transnational economy of desire” (2012). Awareness of increased foreign viewers (and an enduring desire for affirmation from beyond Korea) impacts how performers are filmed and exposed by television shows.23 Performances, circulating internationally, are uploaded and shared on line by company representatives and fans,24 and with the August 2012 release of live performance shows Music Core and Inkigayo on Hulu, they are available for US audiences not just as single-song clips, but as they are seen on Korean television.

The legislation most closely linked with government regulation of K-pop is the Korean Juvenile Protection Law (

In order to protect young consumers, Article 8 explains that the Juvenile Protection Committee can rate media materials to restrict access by minors. Article 9 presents the “Criteria for Deliberation on Media Materials Harmful to Juveniles,” establishing what sort of content should not be allowed. Unfortunately, the vague language of this article complicates enforcement. Finally, Article 11 specifies the self-regulation of harmful materials, making the producers, publishers, distributors and organizations concerned with media materials responsible for determining if materials are harmful with the assistance of the Juvenile Protection Committee. The first paragraph of Article 11 explains:

Frequently, broadcasters slap restrictions or even ban music videos based on content, clothing or choreography.27 In this case, videos are often re-released in versions a bit tamer than the first, or a “dance version” is released for television while the “banned” version—really only banned from Korean TV broadcast— attracts views on video sites such as YouTube. Releasing a video that could be banned may even be used as a marketing ploy, particularly when companies gleefully release multiple versions of videos, allowing them to garner more press attention and exposure for the same song. Big television stations, including SBS and MBC, make an effort to respond to criticism and keep their own noses clean enough to avoid profit-damaging fines or restrictions. They do this by occasionally requesting changes to costumes, choreography, and even silencing swear words: strikingly all the changes they request place the responsibility for content unsuitable for airing before 10 p.m. on the performers, yet as I explain below, these music shows continue to frame performers in an objectifying manner.

Juvenile Protection Law Revisions

Revisions to the Juvenile Protection Law discussed in late 2012 proposed an Rrating for movies, music videos and TV shows that “place an exaggerated sexual emphasis on young singers and bands,”28 however, such language did not appear in the revisions. Kwŏn Sunt’aek, a reporter for Media News (

In the same article, Kwŏn revealed that in 2010, the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family surveyed teenage celebrities and trainees and sixty percent of female teenage celebrities reported that they had been pressured to expose themselves. Although proposed revisions seemed to be focused on protecting young performers from exploitation from within the system, this content was not included in the final revision. In fact the revisions were so toothless that no reports of politicians calling press conferences to brag about their success in protecting youth or morality through the revisions to the law can be found on line. The Ministry of Gender Equality and Family hopes that changes to the law will force more stringent self-regulation by producers who target a teen audience, but since the changes have only been in effect since September 2013, it is unclear if this approach is working.

Can revisions to the Juvenile Protection Law be conducted in good faith when government regulations are attacked by fans as paternalistic censorship? In a recent blog post, Haengbokhan Rami (a pseudonym) complains about “

15One of the many articles on the subject is available at http://www.allkpop.com/2013/02/open-world-entertainment-ceos-appeal-against-his-6-year-prison-sentence-rejected. Accessed 2/22/2013. 16The report is available at http://www.humanrightskorea.org/2012/exposure-of-sex-to-teenagers/. Accessed 2/2/13. 17See more about criticism of Hyuna for her performance in this online article by Lee Kyung-am available at http://global.mnet.com/news/newsdetail.m?searchNewsVO.news_id=201201101806_2696. Accessed 2/4/13. 18See for example this article from Mŏni T’udei http://news.mt.co.kr/mtview.php?no=2013033011538278874. Accessed on 4/04/2013. 19Reports indicated bullying within the group T-Ara in July 2012, according to The Choson Ilbo of July 31st, 2012, available at http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/ 2012/07/31/2012 073101553.html. Accessed 1/29/13. 20Contracts nicknamed “slavery contracts” can tie performers to a management company for seven or even thirteen years with little chance of re-negotiation. Disputes of note include the implosion of the five-member group Dongbang Shingi (Tongbang Sin’gi) (TVXQ, now operating as the two-member Dongbang Shingi and three-member JYJ, the latter under new management), the contract dispute between Block B and Stardom Entertainment that in late August 2013 resulted in Block B moving to a new Stardom-affiliated agency called Seven Seasons, and the dismissal of Park Jaebeom (Pak Chaebŏm) from JYP Entertainment’s group 2PM for undisclosed inappropriate behavior. 21Perhaps if the documentary Nine Muses of Star Empire, which demonstrates the level of abuse endured by the members of the group Nine Muses, achieves success, fans will recognize their own complicity. 22According to columnist “Dana” of Seoul Beats in an April 19, 2012 article entitled “Open World Entertainment and the Ugly Side of K-pop,” available online at http://seoulbeats.com/2012/04/open-world-entertainment-and-the-ugly-side-of-kpop/. Accessed January 29, 2013. 23Although foreign viewers are increasing, some argue that since K-pop remains marginal and unprofitable in the West, claiming that its promotion in the U.S. and Europe is designed to impact the Korean domestic audience. 24For example, for Kara’s comeback performance of “Pandora” on Inkigayo, the two first listed YouTube clips have 52,000 views and 391,000 views as of May 2013. Available at http://www.you tube.com/watch?v=7pMGXis6hSs and http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ave A EAQ cUeY, despite the fact that neither clip was uploaded by “SBS1” the YouTube channel for SBS TV. Accessed 5/6/2013. 25Here I refer to the version enacted 2013.9.23 of law che11673ho; the full text is available at http://www.law.go.kr/법령/청소년보호법. Accessed on 11/7/2013. 26This passage has not changed in more recent revisions, so here I have used the translation of the January 2010 version of the law, available online at http://english.mogef.go.kr/eng_laws/laws_06.html. Accessed on 2/26/2013. 27Banned videos include the original version of TOP’s “Turn it Up” available at http://www.youtube.com/ watch?feature=player_embedded&v=AdPnMoxKOWY, censored for blatant product placement. Ch’ae Yŏn’s “Shake,” available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=o1rkv-ONGwk, was banned for being too sexual. Epik High’s “Breakdown,” available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded &v= sj279u Y7zM4, was banned for being too violent. Lee Hyori’s (Yi Hyori) “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang,” http://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=gzAHCDBXRM0, was banned because it showed illegal activities such as dancing in a street. Brown Eyed Girl’s “Abracadabra,” http://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=z8AVm_ROtDM, was banned for sexual themes particularly BDSM, and because of the kiss at the end of the video. Ava/Lee Jung Hyun’s (Yi Chŏnghyŏn) “Suspicious Man,” http://www. youtube.com/ watch?v=WXVn26GyIpQ, was banned for sexual content. Hyuna’s (Kim Hyŏna) “Change,” http://www. youtube.com/watch?v=G6JppjQSTh8, was slapped with a 19 and over rating. All accessed on 4/10/2013. 28South China Morning Post from October 18th, 2012, entitled “South Korea Tries to Curb the Sexual Exploitation of Underage K-pop Stars.” Available online at http://www.scmp.com/news/asia/article/1063441/south-korea-tries-curb-sexual-exploitation-underage-K-pop-stars. Accessed 1/29/2013. 29The article from March 2013 is available at http://www.mediaus.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=32344. Accessed on 4/3/2013. 30Translation by the author, original reads: 최민희 의원은 “최근 몇 년 동안 우리사회에서 걸그룹 등 아이돌 연예인이 대중음악을 중심으로 큰 인기를 얻고 한류의 중심축으로 등장했다”며 “그 과정에서 연예기획사가 비대칭적 권력관계를 이용해 청소년연예인에게 노출 등 선정적인 공연을 강권하는 사례가 종종 발생하고 있다”고 비판했다. 31This blog post from 2012 can be found at http://blog.naver.com/hopegay/100152136738. Accessed on 4/3/2013.

The confluence of audio and visual stimulation in K-pop is a heady mixture. Today K-pop is most often consumed through visuals—repeated viewing of music videos and videos of live performance become a display of gender normative behavior and a significant way that an awareness of the body is taught to young audiences.32 K-pop has a strong visual component, first because of an emphasis on dance by well-rehearsed young stars. The emphasis on dance and frequency of group as opposed to solo performance is partially because all group members are singers and dancers, who take turns singing (and do not play instruments). Because this means that only one person on stage is contributing a voice to accompany a pre-recorded track, the others are on display.33 Green asserts that displays like this are part of the “delineation of the music beyond the live setting, entering into the musical experience even when the music is recorded” (1997: 24). International fans have repeatedly attributed their K-pop interest to the display of dance, which is unhampered by linguistic differences.

Camera work and the stage presentation by emcees are important framing materials that guide audience reception of performance displays. In music reception, contexts contribute to the listeners’ understanding of the musical meaning (Green 1997: 7). In 2013 the fans of K-pop assert their judgments about new releases through blogs and response videos uploaded to YouTube with many of the same keywords used in the music videos and videos of performances on shows like Music Core and Inkigayo. Although affected by instrumental choices, beat, and other musical cues, most consumers find it easier to frame their response not in terms of the music itself, but through their emotional reaction to choreography, imagery, and the story presented by the lyrics and music video. When the consumer is watching a recording or a televised performance, such as those analyzed here, they may reject a performance as being inferior to previous releases or too similar to another group, or perhaps featuring too much Auto-Tune, yet few responses criticize subtexts or deeper meanings conveyed through the performance. Although this lack of substantial analysis by fans is not unique to K-pop, it is worth noting that in K-pop more so than in other genres, weighty reviews of performances, tours, or releases, if less-than-glowing, can generate massive fan-club anger directed at the reviewer, stifling discourse.

>

K-pop Performance and Objectification

Sexual objectification in popular music is a serious issue with ramifications for the future. Objectification theory holds that women develop their understanding of their own body from observations made by others about women’s bodies or their own body, whether mediatized or face-to-face. Objectification theory clarifies that after being exposed to an overemphasis on appearance, internalization of observers’ perspectives causes people to self-monitor chronically (Heflick and Goldenberg 2011, Heldman and Wade 2011). Objectification is not a new issue in the United States, but “female sexual objectification has become increasingly ubiquitous and normalized” (Heldman and Wade 2011: 157). In Korea sexual objectification has become more prevalent, and this study helps unveil specifically how music shows on television contribute to this objectification.

In the world of K-pop songs are promoted through concerts recorded in front of live audiences on a weekly basis for each of the major networks. The hottest stars currently promoting a release appear on each show; Saturday night’s Music Core and Sunday night’s Inkigayo will have a nearly identical line-up of artists performing the same songs, but in different costumes. In the following section I will focus on the performance frame: how the video production crew captured the performers, and the manner in which emcees introduced performances to identify some of the ways that the frame constructed by SBS and MBC objectifies the performers. My concern with women’s depiction in performance, in comparison to men, alongside my attention to the government’s discussion of tightening regulations on broadcast and its impact on broadcasters, motivated me to choose six videos for close reading. I sought to answer these questions:

The K-pop emcees on shows such as Inkigayo and Music Core are other young stars. There are three reasons why this should be unsurprising. First, the audience attends the performances or views these television shows in order to see K-pop stars; television stations are simply providing what the audience wants. Second, for K-pop stars various television appearances are a major part of their activities (whether on talk shows, game shows, and reality shows). Third, emcees are generally educated about the genre they present.

Korean traditional music and dance performances are often emceed by highly knowledgeable professors, performers, and independent scholars (Saeji 2012). This is also generally the case in other performance contexts (e.g. Gelo 1999: 42). Therefore, although often in their late teens or early twenties, the K-pop stars emceeing performances can be seen as highly knowledgeable insiders in the performance of Korean popular music. Observing the emcees’ performances, however, a critical viewer may wonder what they contribute, besides “star wattage.” Unlike the emcees observed by Gelo, or the Korean emcees for traditional performance, Inkigayo and Music Core emcees do not add to the performance by providing background information or contextualization. They do not educate the audience (at least, not about music). Their performance is, in many ways, part of the same spectacle as that of the performers they ostensibly introduce: they are performing stardom, and the music shows offer fans an opportunity to get to know the emcees better. For example, on the January 13, 2013, Inkigayo program, the three emcees appear after the first song and discuss activities appropriate for cold weather. After discussing winter activities, they turn to the music:

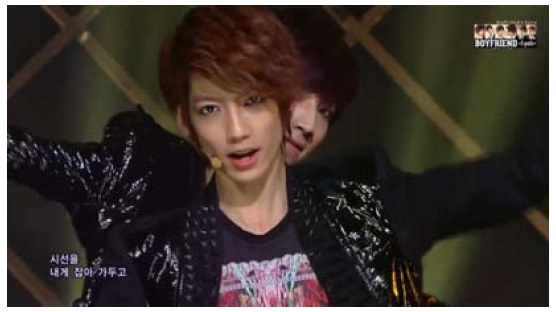

In the example above, the performances are described as “hot,” “fatal yet masculine” as “pumping out vital energy” and only in one case, that of 2BIC, is the music (“sensational melody”) prioritized. However, the two performers of 2BIC are overweight men; if they were conventionally good-looking by Korean standards, would their appearance have been mentioned instead of their music? The next time the emcees appear, they discuss how exercising in winter will dry out one’s skin. Kwanghŭi recommends (and demonstrates) spray-on lotion, while Hyŏn-u advises viewers to drink citron tea because it is full of vitamins. The lack of discussion of music is clearest when the featured “comeback” performance of the week is introduced. The song, “I-Yah,” by the group Boyfriend represents a turning point in Boyfriend’s image: the K-pop English language website of choice, allkpop.com, reported that for “I-Yah” Boyfriend’s “members are letting go of their boy-next-door image, leaving fans swooning once more with their ‘homme fatale’ concept.”40 None of the K-pop news sites discussed musical growth or development, or changes to the music, as Boyfriend premiered their new material. All discussion centered on image:

Obviously, the questions in the interview could be pursued to reveal additional depth, but short and superficial answers are followed by the next question, without pause. At the end of the interview, the audience is not likely to know anything new about the group, although they did have an opportunity to cheer for the group members. This section of the television show, conducted from 31:10 to 32:30, has primarily served to prime the audience to perceive Boyfriend as more masculine than at the time of their previous release. The February 3 rd , 2013 Inkigayo show features the same three emcees and the emphasis on appearance is again preserved, this time through an initial discussion about fashion. Although all three discuss fashion, the viewer again is left with no new information, and the entire conversation (from 3:05 to 4:44 of the program) serves only to demonstrate the personality of the three emcees. None of the information in this entire exchange allows the audience to approach the performances for their musical value, but rather, to see the performers (including the emcees) as clotheshorses, from the start when IU states that the performers for the day are “attractive.” The emcees return to the fashion theme later in the program, Kwanghŭi claims that his look is complete with a necklace, IU has a bow in her hair and Hyŏnu is wearing a stylish watch. During another emcee segment they discuss dieting during spring break. Later in the show the emcees conducted an interview with Sistar 19 (from 57:43 to 57:59):

Here as well the emcees do not focus on the music, although the song is described briefly by Bora. Ultimately, the emcees on the show teach the audience to experience the performances visually, not aurally. For example, seeing the dance movement makes Hyŏnu fall in love with the performers. Some reasons why interviewees are not asked about the music specifically might be because the performers themselves have not participated in the construction of the song—in almost all K-pop performance, the song subject, lyrics, instruments, choreography, and image to accompany the performance were chosen independent of the performers. Interview questions exploring the inner motivation and artistic choices behind the song would thus be uncomfortably hard for the performers to answer. The young emcees are aware of this fact, and are sensitive to what subjects are appropriate.

By contrast Music Core does not include interviews with performers. The three emcees, Girls’ Generation members Tiffany, Taeyeon (T’aeyŏn), and Seohyun (Sŏhyŏn) tend to much shorter and even less informative turns at the microphone than the emcees on Inkigayo.42 In the introductory emcee appearance from February 2nd, 2013 (3:20 to 4:20), the three idols performed celebrity status.

The actions of the emcees from Girls’ Generation demonstrate the primacy of performing popularity, not performing knowledge. Taeyeon in the first section and Seohyun later in the program exhibit

Viewed on screen, “the woman’s beauty, her very desirability, becomes a function of certain practices of imaging—framing, lighting camera movement, angle” (Doane 1982: 79). It is impossible to overemphasize how important imaging practices are in constructing the gender in K-pop performance. In examining the camera techniques used on these two television shows, I was influenced by political scientist Caroline Heldman’s seven-question sexual objectification test used to determine if images in print advertising are sexually objectifying.44 For camera techniques used for these televised music performances I developed the following questions. First, does the camera isolate a sexualized part of a body (buttocks, legs, genitals, breasts)? Second, does the camera pan across a person’s body in a way that guides the eye to a sexualized part of the body or is designed to be sexually stimulating? Three, does the camera utilize upwards angles that emphasize the body and de-emphasize the head? Watching the performances I answered these questions in cooperation with an understanding of the song subject, the presentation and performance of gender roles (gender-specific dance motions, costumes), relationships shown between women or between men, expression of sexual desire or sexuality, and the image generally associated with the artist.45

In the performances analyzed for this paper, I found that SBS and MBC used camera angles to emphasize one body part over another, and isolations of specific parts of the body in a manner that could inarguably be read as objectifying. The use of close-ups of sexualized body parts and faces turns performers into a “cutout or icon” and destroys “the illusion of depth” in a performer (Mulvey 1975: 12). By breaking women down into their parts, and by extension repeatedly screening these body parts in a sensuous manner, objectification becomes normalized. Notably, the emphasis on the legs of the members of Girls’ Generation has been called “stereotypical of fetishized femininity” (Kim YR 2011: 339).

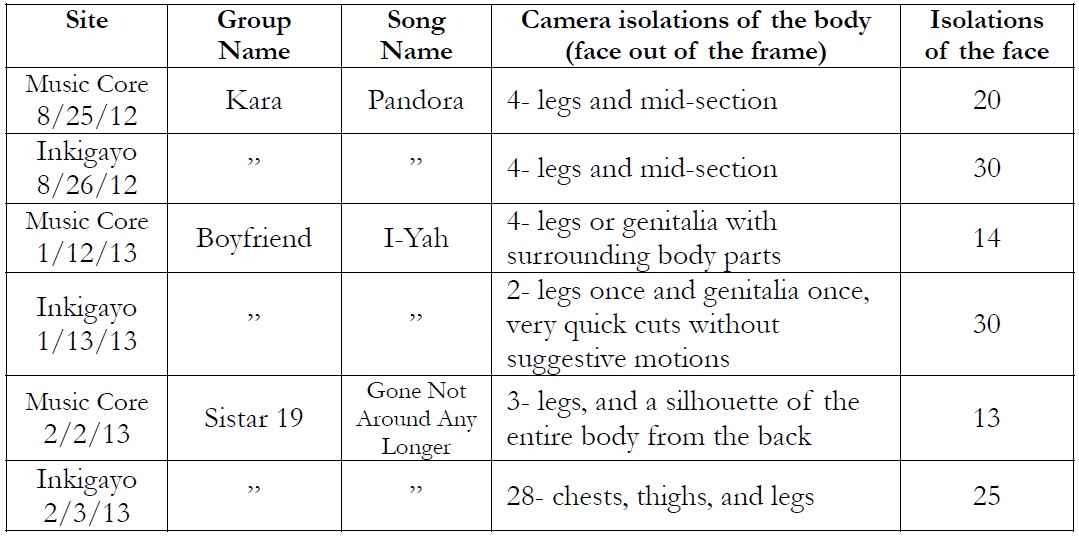

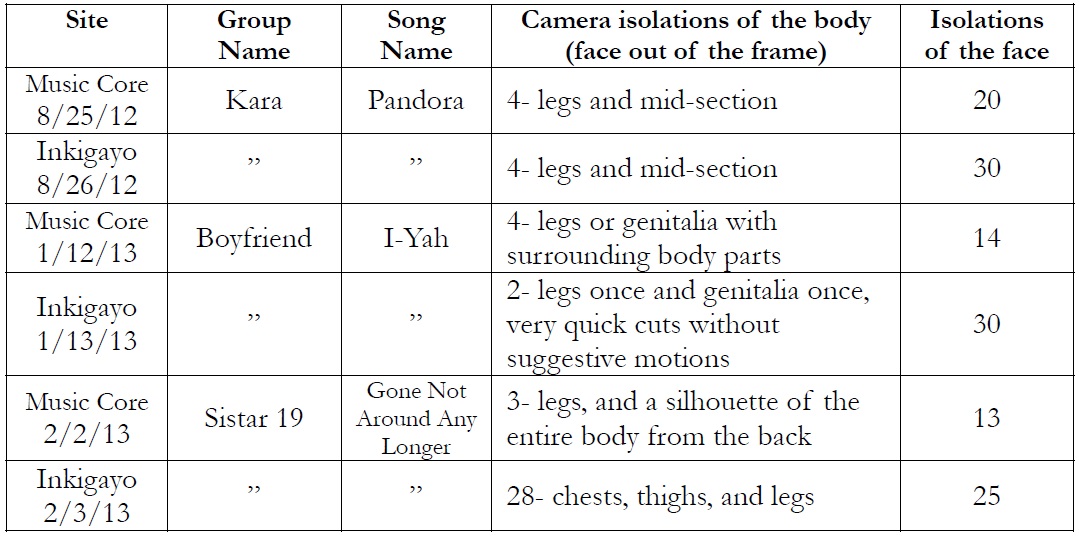

Each of the six performances I chose for close viewing were “comeback” performances—when the evening’s broadcast highlights the release of a new song by a popular group or artist. Comebacks are not broadcast live: they are prerecorded (in front of a live audience) on special sets, and the video footage is carefully edited (more carefully than the performance of the same artists a week later when they are no longer the “comeback” of the week). In general, comeback performances incorporate more cameras and more transitions between different cameras than is used on the performances for the week that are not comebacks. I counted each instance of focus on sexualized body parts, and followed this up with a frame analysis, clicking through the videos, frame by frame, I was able to identify similarities and differences in presentation and camera techniques. In Table 1, below, the exact number of isolations of the body (without the face visible) and of the face (with at most the torso visible) is presented for each performance, along with details about which body parts were the focus of the camera.

[Table 1:] Quantifying objectifying videography

Quantifying objectifying videography

Kara’s “Pandora”

Kara’s performance of “Pandora” at their comebacks on August 25th on Music Core and 26th on Inkigayo was controversially sexual. In the song they sing:46

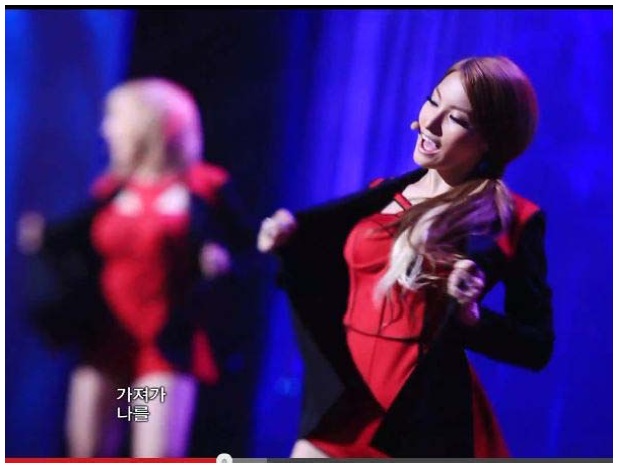

The performance choreography highlights the physical attributes and desirability of their body—and the lyrics describe a man powerless to resist the singer(s). Kara’s performance costumes are also highly gendered—resembling a teddy with corsets under a loose jacket. Among other motions, their jackets are popped open and then the jackets fall off the shoulders of the performers, prompting a fleeting fantasy in the viewer that they will undress.47 In another move the women fondle their own body with their arms crossed—so that the touching hand appears to be someone else’s, perhaps that of the viewer. They also whip their hair and run their hands down their body while looking at the audience. The camera emphasized each of these sexualized moments in the choreography. Although popular with fans, this performance was frequently used as an example of performance choreography and dress that had overstepped the boundaries of acceptability. I conducted a close viewing using frame analysis of the performances on both Inkigayo and Music Core. There were four isolations of the body, including the mid-section and upper legs, on each show.

Boyfriend’s “I-Yah”

The song “I-Yah” by Boyfriend is a sweet protestation of teenage love. In the commercially produced music video, several boys love one girl, there is trouble with authority (a male teacher ready to punish late students), and the important final triumph of love (the two ride off on a motorcycle). However the mild truancy, fighting, and corporal punishment in the video angered some conservative viewers who felt the wrong message was being promoted. The lyrics are stereotypical of pop love songs, penned with little imaginative vocabulary:48

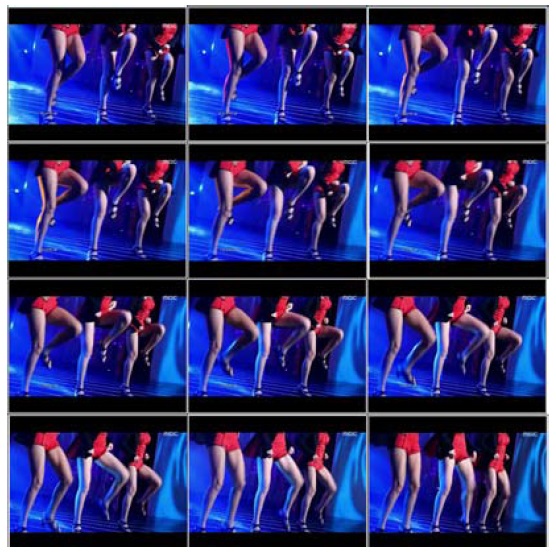

The live performance of the song features highly gendered choreography— specifically the young men run their hands down their torsos, grab their genitalia, and rotate their hips upward, still cupping their crotch. The group members also pop their chests, slick back their hair, and hook their fingers in their belts. Although the official music video downplays the choreography and focuses on depicting the love story through a complex series of scenes revolving around the female love interest, in the live performances the choreography is emphasized.

Conducting a close analysis of these two performances, it was obvious that the camera, especially on Music Core, emphasizes the genitalia-grabbing action through zooming in on the hand and hips. On Inkigayo the camera pulls closer only once, but moves upwards to the head, so that the hand and the hips are no longer visible during the grab and hip thrust. Although there are isolations on Inkigayo of the lower body, twice, these are momentary flashes of the legs with the hands in the belt, and of the crotch but without the caressing hand. The isolations are so brief that they are almost unnoticeable without watching frame-by-frame.

Sistar 19’s “Gone Not Around Any Longer”

Sistar, and the subgroup Sistar 19, have been marketed in a sexually charged way starting with their first release. In the interview quoted earlier, the emcees refer to the name Sistar 19—the stated rationale behind the name is that 19 is the age at which one is neither girl nor woman, or both simultaneously. This magical, liminal stage has already passed for Bora and Hyorin, but the name of the group is meant to evoke a fantasy of virginal awakening. For this song, the choreography accentuates the breasts (natural or not, unlike most Korean women, these two have full bosoms), and the buttocks. Sinuous upper body movements with a hand on or near the breasts alternate with steps performed with the back arched, the buttocks thrust outwards, and the legs bent slightly at the knees. Even more noticeable, however, the song includes a large glass table and the two singers polish the table with their backsides, gliding from side to side and rotating on the smooth surface, leading to YouTube comments such as “I really envy that bench.” The song is about a woman’s feelings after a man has left her: 49

The slow, sad lyrics are those of a disempowered woman, and the openly sexual choreography reinforces sexual objectification of the two women. Elements of subservience are introduced both in costuming and in the costuming of the (all female) back-up dancers. On Music Core the duo wore a skin-tight top and matching shorts, heavily layered in jewelry, particularly wide chains symbolically controlling them in the form of a collar and a chastity belt. On Inkigayo they were dressed in an oversized shirt symbolically representing the last connection to the man who presumably abandoned the shirt along with the woman. On both shows the back-up dancers wore blindfolds with long trailing ties in back, bringing to mind a leash. In these performances two men also appear, briefly, and manipulate Hyorin and Bora as though they were puppets.

Image 6, below, highlights the current trend of wearing an oversized shirt with shorts so short the viewer wonders whether the women are wearing shorts, or underwear. Interestingly, clothing has recently been re-politicized. In March President Park spoke out against this trend in a way that has been likened to her own father’s policies on mini-skirts, but by May she was claiming it was a misunderstanding.50 During the interim, various news reporters published increasingly overstated rhetoric and “news from the street” as they interviewed young women who claimed to not know if they would risk a citation if they wear their stylish new ensemble.51

Overall, the camera techniques and filming by both shows for the three songs primarily tended to utilize stationary camera shots, as compared to zooming or panning. Capturing the current singer as he or she delivered a line was a major reason for camera changes or movement, and both Boyfriend and Kara constantly switched singers from one line to the next. Sistar 19 relied primarily on Hyorin’s exceptional vocal talent, and rather than staying with her as she sang what disgruntled YouTube commenters, presumably fans of Bora, called “95% of the lyrics,” the camera included more body isolations on Inkigayo and more long shots on Music Core. However, on both shows shots that included zooming and panning were of longer duration, this left an impression that the camera zoomed often. Zooming was both in and out, with zooming out more pronounced. In all six videos often the camera would begin to zoom in followed by a cut to a closeup shot from a stationary camera. Close panning shots of women often followed the women’s hands to their bodies, or the men’s hands to their faces.52 Panning across the chest, or up the body, at times felt disturbingly like the viewer was engaged in stroking the performers. The camera, especially on Inkigayo, would also pan across the stage from side to side while on Music Core tilted camera angles were more common. Originally I also counted the upwards camera angles which emphasized the bodies and de-emphasized the identity of the performers, but due to the large variation in degree of upwards angle and the use of panning and zooming in those shots I found it difficult to count accurately. However, it was clear that upward angles were usually the beginning of a simultaneous pan and inwards zoom.

Laura Mulvey was one of the first scholars to discuss gaze in how we consume movies, theorizing that the act of watching a movie is in itself a manifestation of Freud’s scopophilia (1975: 9). In her influential work, Mulvey theorizes the male gaze as active and the female gaze as passive, and decades of scholars since have expanded her argument and applied it to everything from music videos to cyber avatars. According to Mulvey’s analysis, in K-pop some fans (those sexually attracted to women) may be sexually stimulated by the sight of Kara and Sistar 19, while others (presumably most of the female fans) identify with the performers. The passive female gaze accepts a performance (and choreography, lyrics, costumes) crafted for an active, male, sexually objectifying gaze.

What is the impact on young female fans as they identify with the sexualized performers? Close frame-count analysis of these music videos facilitated an awareness of how the images in television performance are crafted, and who is meant to observe the performances. If we pre-suppose a construction of the gaze (via the camera) as male, the camera should treat the performances of women and men differently, emphasizing different body parts, and either moving towards or away from the performers. Nicola Dibben (1999) also posits that direct connection with the viewer through close-ups is part of framing a performance for a male gaze. Despite gendered choreography, the viewer in K-pop is a fan of indeterminate sex. Fans of groups like Kara and Sistar (or Sistar 19) are not overwhelmingly male, nor are all of Boyfriend’s fans female. Viewing Kara’s performance on Inkigayo with a colleague, he remarked at the screams from what were clearly female fans in the audience.53 Although girls are seemingly more involved in K-pop fan activities than boys, successful groups and solo artists in the second decade of the 21st century are more often female than male.54

After viewing these six performances, as well as all of the other performances in each of these TV shows (the entire shows from August 25th and 26th, 2012; January 12th and 13th , 2013; and February 2nd and 3rd, 2013), I returned to my original three questions. First, are SBS’s Inkigayo and MBC’s Music Core presenting the same performers performing the same song in a different way? I believe that the differences between Inkigayo and Music Core are stylistic differences: they strive for a distinct image, which is difficult when staging a lineup of performances that in important ways is otherwise identical. Nevertheless, they use different shooting and directing teams, different lighting and backdrops, and different emcees. Inkigayo prefers tighter close-ups of the faces of the idols than Music Core. Music Core incorporates a soft-focus effect that Inkigayo does not use. Special lenses allowed the Music Core performance to show one member in tight focus while others become part of a blurry background. Through use of this technique, the television show further controlled the viewer experience.

Second, are SBS and MBC presenting men differently than women? It appeared that the two television stations were following the cues provided by costuming and choreography, whether performed by women or men. At first I considered the sexualized choreography of Boyfriend and posited equalopportunity sexual objectification. I came to realize that boy groups sometimes utilize an overtly sexualized performance for one or two songs to demonstrate increased maturity (as a dramatic departure from pre-teen asexuality demonstrated in earlier releases for groups, like Boyfriend, that debut with very young members). Although there has been increased sexual objectification of the males in K-pop in advertisements and pictorial displays of ripped abdomens as detailed by Epstein and Joo (2012), in performance blatant sexuality, release-after-release, is limited to one Korean superstar, male solo artist Bi (Pi) (he uses the name Rain internationally). This suggests that in Korea idols can be objectified regardless of their gender, based on decisions of their management company. However the sexualization of Boyfriend works to achieve an image goal ultimately empowering the performers as the subject, whereas female sexualization presupposes the female as object.

Third, are SBS and MBC responding to popular criticism of sexualized performances by shooting in a more demure way in early 2013 than they shot Kara in August 2012? Considering the blatantly sexualized way that Sistar 19 was presented by Inkigayo, and the crotch-grab close-ups of Music Core’s presentation of Boyfriend, there does not seem to be a reduction in sexual expression on the television stations. If Kara’s 2012 performance was considered over-the-top, how could Sistar 19 and Boyfriend not raise eyebrows in 2013?

After considering the construction of femininity in K-pop during several months of reading and close analysis of videos, I increasingly felt the male hand in the filming decisions made by the crew of Inkigayo, including Inkigayo’s hesitation to zoom in on Boyfriend’s members grabbing their genitalia. Yet when I checked the staff members on the website, I found that the producer, both directors, and one of three camera operators were men, while two cameras were operated by women and the host of the show was also a woman.55 Although I felt that Music Core’s videography seemed perhaps slightly more female oriented, I never would have guessed that all the camera operators were women. Visiting the website for MBC’s Music Core I found that of eight listed staff members, only one of the two co-directors was a man—all the camera operators and the assistant director were women, as well as the main producer.56 The sex of the camera operators and directors clarified what seemed to be a more fetishistic and objectifying presentation of women on Inkigayo, with the male gaze (and hand) clearly present in videographic decisions to isolate sexualized body parts and pan across the female body. The male directors of Inkigayo may have found it less comfortable to objectify Boyfriend than the female-dominated team at Music Core.

The Music Core emcees, three members of Girl’s Generation, seemed disempowered. Their scripted

32Please note that the author is aware that the “live” performances are often lip-synched, and that when they are sung live the background instrumental and vocal tracks come from the studio album. The performance on stage becomes much more about performance of stardom and less about performance of musical competence in such circumstances. 33The emphasis on appearance in Korean music means that performers are recruited based on appearance (or potential appearance)—despite this many, even most, get plastic surgery. Beauty has been so successful in attracting audiences even to poor singers that the government, in a project to market tourism to Korea through fusion-traditional music, formed the now-defunct group Miji. Miji featured young, beautiful traditional musicians often in revealing clothing performing fusion music (see Finchum-Sung 2012 for more on this case). This group was, in part, copying China’s more successful 12 Girls Band. Yang and Saffle explain that even enthusiastic fans call the 12 Girls Band “more beautiful to look at than listen to” (2010: 97). 34Yi Hyŏnu is an actor who has appeared in films and had a prominent role on several recent television dramas. He was born in 1993, making him an appropriate age for connecting with Inkigayo viewers. 35Translation was based on subtitles for the show available on Hulu, but in several cases rendered more accurately by the author. 36IU is one of the biggest names in K-pop. She is well liked and has multiple TV appearances including important roles in dramas, holds multiple endorsement contracts, and is a popular solo singer. Born in 1993, she debuted in 2008 and was already a household name by 2009. 37Kwanghŭi is a member of the group ZE:A. Kwanghŭi (born in 1988) has appeared in television dramas and the reality show “We Got Married.” 38In Korean pop parlance “comeback” is used anytime a performer or group releases a new song after having taken a break for touring or recording. It is acceptable to use “comeback” when someone has only been off the show for a period of three or four months. 39A few years ago, the big management companies realized that a way to get more mileage out of their stars was to have them also release solos, or songs performed with only some of the members of their group. These are often released as singles. Sistar has a subunit called Sistar 19, Super Junior’s Chinese (Mandarin)-speaking subunit is called Super Junior-M, and here we can presume that the H in Infinite H stands for hip-hop. 40Available at http://www.allkpop.com/2013/01/boyfriend-come-back-with-i-yah-on-music-core. Accessed on 2/22/2013. 41Ironically, this statement is not true. The two performers were born in 1990 and 1991, making them both in their twenties. However, nineteen is the legal beginning of adulthood in Korea; nineteen-year-olds may vote and drink, and men can begin their mandatory military service. 42These three members for Girls’ Generation also record and perform as the sub-unit TaeTiSeo. 43In Korea during Lunar New Year, children bow formally to adults, particularly members of their own family, and receive an envelope with some crisp new bills in return. Teenagers now expect these envelopes, but since Taeyeon was born in 1989, she should be past this. 44Caroline Heldman presented a lecture on “The Sexy Lie” at a Ted-x Youth event. The video is available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=kMS4VJKekW8. Accessed 1/15/2013. She also explains the test on her blog, http://carolineheldman.Word press.com /2012/07/02/sexual-objectification-part-1-what-is-it/, accessed 1/16/2013. 45My approach was clarified after reading an excellent article on blackness in music videos by Rana Emerson (2002). 46Han’gŭl (Korean script) and translated lyrics from the website http://starryangell.blogspot.com/2012/08/kara-pandora-hangul-romanization-english.html. Accessed on 5/1/2013. 47The off-the shoulder motion was considered so hot, that even with skin-colored shirts giving an illusion of more exposure than in reality occurred, another major music television show, KBS’s Music Bank, considered asking for a choreographic change if Kara wanted to perform on KBS. Ultimately KBS decided not to request a change. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pandora_(Kara_song). Accessed on 4/01/2013. 48I copied the Korean lyrics from this page: http://reatnomae.blogspot.com/2013/03/boyfriendi-yah-hangul.html. Accessed on 5/1/2013. The English lyrics I copied from http://kromanized.com/2013/01/09/rom-eng-lyrics-boyfriend-i-yah-EC%95%84%EC%9D%B4%EC %95 %BC/#sthash.W8L7ISV0.dpbs. Accessed on 5/1/2013. 49The lyrics were copied from this site: http://jumpersjump.blogspot.com/2013/01/lyricsistar19-19-gone-not-around-any.html#ixzz2SdFWGJut. Accessed on 5/1/2013. 50An article from 5/8/2013 claims President Park was misunderstood http://www.pressian.com/article/ article.asp?article_num=40130311172826. Accessed on 5/8/2013. Earlier articles are fairly represented by this one from 3/21/2013 by Frances Cha, http://www.cnn.com/2013/03/21/ world/asia/south-korea-overexposure-law. Accessed on 5/8/ 2013. 51Dana, a writer for Seoul Beats, does an excellent job criticizing the reportage on this issue in an article from 4/5/2013. Available at http://seoulbeats.com/2013/04/calm-down-hyori-southkorea-isnt-banning-miniskirts/. Accessed on 5/7/2013. 52In personal correspondence on 4/09/2013, Timothy Gitzen pointed out the particular use of hands to draw attention to the face of boy bands and male solo performers. 53Thank you to Joshua Van Lieu for this observation. 54In the early days of K-pop successful groups were more often male—early hits following Seo Taiji and the Boys included “boy” groups such as H.O.T. (debuted in 1996), Jinusean (1997), NRG (1997), Sechs Kies (1997), Shinhwa (1998) and g.o.d. (1999). During those early years the major female groups were S.E.S., (1997) Baby Vox (1997) and Fin.K.L. (1998). Analysis of the complex reasons why female groups increasingly dominate K-pop would be a fruitful topic—is the greater sexual, economic, and cultural liberation of women in Korea coming at the expense of increased exploitation and objectification? The Atlantic addressed K-pop girls groups and reasons for their success in several articles, including an article from fall 2011 that asserts that K-pop girl groups are so successful in Japan because of a more sexual image: http://www.theatlantic.com/ entertainment/archive/2011/09/how-korean-pop-conquered-japan/244712/ and this article from early 2012 about the chances of a Korean girl group becoming big in America: http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2012/01/does-korean-pop-actually-have-ashot-at-success-in-the-us/252057/. Both accessed on 11/7/2013. 55The production team is listed at the bottom of the website in pale lettering--http://gayo.sbs.co.kr/. Accessed on 4/15/2013. At the time of this research the staff members were producer Choi Yŏngin; Directors Kim Yonggwŏn and Ryu Sūngho; host Yi Haeju; Camera Operators Kim Ch’anghee, Kang China, and Kang Panbi. 56The entire production team is listed at this address: http://www.imbc.com/broad/tv/ent/musiccore/pd/. Accessed 4/15/2013. At the time I accessed it the staff members were coordinator Cho Heejin; Directors Sŏn Haeyun and Cho Ukhyŏng; Assistant Director Kang Sŏnga; Camera Operators Kim Sŏnhae, Kim Soyŏng, Chŏng Taeyŏng, and Ŏm Seūn.

At present the dangers to women in a society that is comfortable sexually objectifying women (as long as they are at least nineteen) on national television are significant. Beyond complicity with teaching men and boys that women can be treated as sexualized objects, young women (and men) continue to be faced with evidence that thinness and conventional beauty are desirable characteristics, contributing to the prevalence of dieting, plastic surgery, depression, and youth suicide. The Korean government repeatedly attempts to fix social problems through ineffective paternalistic measures. Last time the Juvenile Protection Law was amended the revisions addressed Internet addiction by requiring Internet gaming services to shutdown access for minors (under 16) from midnight to 6 a.m. and the 2013 revisions require that commercials for loan agencies not be shown between 10 and 10.57 So far, the Juvenile Protection Law’s articles related to televised performance make it clear that the media producers and broadcasters are responsible for their own content. But, just like minors circumventing restrictions on late-night gaming, the media has avoided making any significant changes, such as changing how they frame performances. Media producers such as Inkigayo and Music Core, if truly committed to self-regulation, could agree to guidelines for music shows that would reduce the objectification of performers. The emcees could be directed to comment on factors unrelated to appearance or sex appeal (at least most of the time). Camera operators could be instructed not to use the camera in a way that overemphasizes the body of any performer (man or woman), abandoning techniques such as up-angled shots and isolations of sexualized parts of the body. Such voluntary restrictions would allow the performers to continue to perform their music as they (or their management company) choose, but broadcasters would no longer be complicit in sexual objectification. It is time for broadcasters to take responsibility for their role in increased sexual objectification of K-pop.

Yet even this action will not go far enough—there is no single solution or single legal action that can ceremoniously ‘fix’ the problem of entrenched gender roles and sexual objectification. Perhaps the most important step would be for a Korean star to assert her own agency and power. Fung and Curtin (2002) explain how Faye Wong transformed herself from a manufactured Canto-pop star (despite being from mainland China and not from a Cantonese speaking area) into an assertive and independent self-managed woman. Through this transformation, Faye became “something of a popular heroine, especially among young women seeking lifestyle alternatives and fantasizing about gender relations outside the well-worn conventions of the pop music industry” (2002: 274). Faye was able to complete this transformation after amassing the cultural and economic capital necessary for self-empowerment. A similar story may emerge in the future in Kpop. Not only are there some newer groups that are promoted as being more empowered, but some of the stars with staying power and large fan bases may, at the end of their current contracts with major entertainment companies, seek a new direction. Just as in Faye’s case, a popular female star espousing independence and embodying the dreams of many young Koreans could remain commercially viable without needing to over-subscribe to disempowered models of femininity. As the K-pop fans and performers mature, I am hopeful that an artist such as BoA could model a new type of empowered female celebrity.

57The Juvenile Protection Law was revised in April 2011 to protect youth from excessive online gaming. To read more about this issue, I recommend starting with the webpage of Global Voices Online, a free speech advocacy group. Available at http://advocacy.globalvoicesonline.org/2013/01/19/south-korea-stricter-online-games-regulations-face-discontent/. Accessed on 5/9/ 2013. This news story describes the more recent restrictions on commercials: http://www.asiae.co.kr/news/view.htm?idxno=2013032317100718464. Accessed on 11/8/2013.