Our visual world is filled with events and objects that are constantly changing. Although phenomenological perception of a scene we experience is often vivid and seamless, our visual system often fails to notice what changes happened (Rensink, 2002; Simons & Ambinder, 2005). Likewise, the representation of a visual scene is sparse(Intraub, 1997) as evidenced by poor transsaccadic memory (Irwin, 1991), and visual working memory can store up to only four objects (Cowan, 2001; Luck & Vogel; 1997).

Such limited capacity forces the visual system to develop strategies to achieve an economical representation of a visual scene, and attention has been considered as one of the most prominent processes traditionally. Attention only selects relevant information among multiple visual stimuli to meet one’s current objective. In this paper, we suggest that suppression serves the same goal as attention, to achieve an economical representation. We define suppression as placing visual stimuli outside of awareness despite their physical presence, resulting in an experience akin to actual physical absence of these stimuli. Suppression differs from complete removal of the stimuli, however, because suppressed stimuli—although invisible— still can influence later processing in various ways (Merikle, Smilek, & Eastwood, 2001). In this paper, we focus on rivalry suppression where one of two different stimuli presented to different eyes becomes invisible. Rivalry suppression differs from attentional suppression because attention can both increase and decrease the effectiveness of rivalry suppression (Shin et al., 2009;Jung & Chong, 2014). Suppressing stimuli may be a means of reducing the mental effort required for conscious processing (Kahneman, 1973).1 Bolstering this idea, the visual system appears to store a vast amount of information without the observer’s awareness (Jiang, Song, & Rigas, 2005), and thus it saves mental effort compared to conscious storing of these information. In addition, suppression may reduce processing demands by decreasing the strength of stimuli (Blake, Tadin, Sobel, Raissian, & Chong, 2006).

We propose that suppression, much like attention, plays an important role in achieving an efficient representation of a complex scene. While attention helps the visual system to achieve efficient processing by filtering out irrelevant information, suppression reaches the same goal by maintaining possibly necessary information without conscious effort and high processing demands.

Despite the notion of attention and suppression having a common computational mechanism (Ling & Blake, 2012), one reason why these two processes have not been considered as serving a common purpose may be due to different perspectives in the two fields. The functional role of attention, which William James (1890) has defined as taking possession of one among multiple objects, has been considered as the selection of only the information that is relevant to a current goal. One prominent attention model, the biased competition model (Desimone & Duncan, 1995; Reynolds, Chelazzi, & Desimone, 1999), argues that attention resolves the competition that exists among multiple objects—from which, for further processing, the visual system must select only a proportion of —in a limited visual space. Where this selection occurs and how it helps the visual system to cope with complex environments have been the major questions in the field (Broadbent, 1982 vs. Deutsch & Deutsch, 1963).

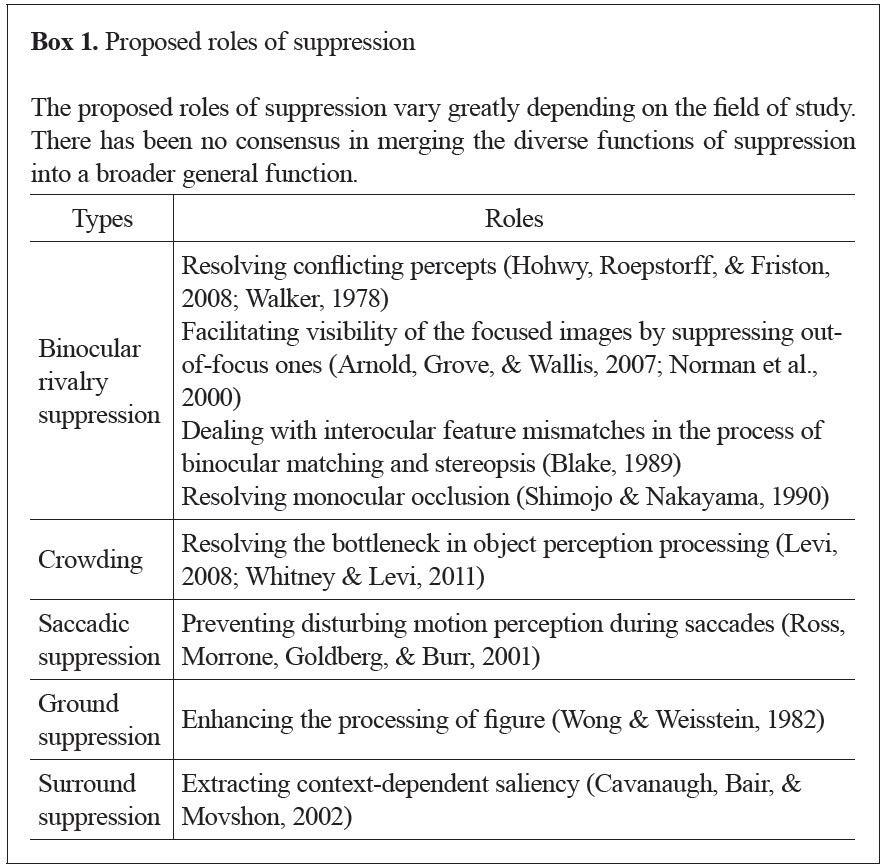

On the other hand, studies of suppression have not yet fully agreed on its purpose. For example, the role of binocular rivalry suppression is often suggested as resolving seemingly conflicting percepts (Blake & Logothetis, 2002). Another suggested role of rivalry suppression is helping one to maintain focus by placing blurred (out-of-focus) images outside of awareness (Arnold, Grove, & Wallis, 2007; Norman, Norman, & Bilotta; 2000). The suggested roles of suppression in other phenomena are even more diverse (see Box 1). No one, however, has yet interpreted suppression as a process to overcome our limited visual capacity, as attention has been understood. Among several other phenomena, we focus on suppression due to binocular rivalry in this paper (Kim & Blake, 2005). In rivalry suppression, a dominant stimulus suppresses another stimulus presented to the other eye, making it invisible (Blake, 1989). Rivalry does not require additional stimuli or physical alterations to the stimuli to change their visibility, unlike other types of suppression (Kim & Blake, 2005).

To this day, attention and suppression have been studied separately because their effects on visual awareness act in opposite fashion; one improves the quality of perception (Carrasco, Ling, & Read, 2004) while the other degrades it (Ling & Blake, 2009). Here, we propose a new conceptual angle to rivalry suppression, targeting on its function as reducing the burden on the visual system. In support of this view, we will review various pieces of evidence that show similarities between attention and rivalry suppression. We first interpret attention and suppression as being related via consciousness. Phenomenally speaking, the effect of attention on unattended stimuli appears similar to that of suppression (Mack & Rock, 1998; Most, Scholl, Clifford, & Simons, 2005). Moreover, attentional selection and rivalry suppression share common neural correlates in terms of initiation (Carmel, Walsh, Lavie, & Rees, 2010; Yantis, Schwarzbach, Serences, Carlson, Steinmetz, Pekar, & Courtney, 2002), and their effects are more pronounced in higher visual areas than in early visual areas (Kastner & Ungerleider, 2000; Nguyen, Freeman, & Alais, 2003). Based on these similarities, we propose that attention and suppression serve a common purpose: reducing the burden on the visual system to cope with a complex scene.

1Despite additional efforts needed for conscious processing, conscious processing is more advantageous in some area. For example, conscious processing can be more flexible than unconscious processing (i.e., it can utilize a strategy during a task, Cheesman & Merikle, 1986).

Attentionand Suppression as the Two Sides of Consciousness

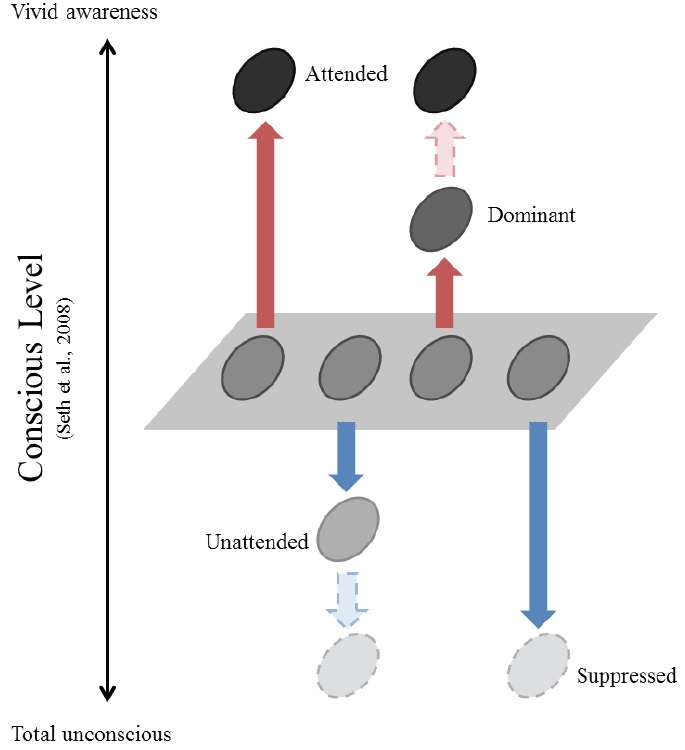

While the relationship between attention and suppression has not been explicitly discussed, the connection of each to consciousness has been suggested independently. Attention has often been thought of as a gateway to consciousness (Posner, 1994) or a catalyst for verbal access to the contents of consciousness (Lamme, 2003). In support of this notion, different forms of attention correspond well to different levels of consciousness (Cohen, Cavanagh, Chun, & Nakayama, 2012; Marchetti, 2012, but see also Koch & Tsuchiya, 2007). It has also been suggested that consciousness and its counterpart unconsciousness should be investigated simultaneously (Crick & Koch, 1998). When suppression is regarded as a means of blocking stimuli from reaching consciousness, it reduces conscious perception. In contrast, attention enhances conscious perception. Therefore, attention and suppression may be linked to be manifestations of changes in consciousness, albeit in an opposite way (Figure 1).

This relationship becomes evident when considering what happens to unattended information. Unattended information is subject to attentional suppression. Multiple stimuli compete for the limited capacity our visual system, especially when they are present within the same receptive field (Desimone & Duncun, 1995; Kastner, De Weerd, Desimone, & Ungerleider, 1998; Reynolds, Chelazzi, & Desimone, 1999). The visual system selects a behaviorally relevant subset of the stimuli in the visual field and suppresses the rest. The selected stimuli are preserved for the next stages of information processing, and the unselected—i.e., unattended—stimuli are ‘less’ processed compared to those that are neutral, where attention is not given to any of the items in a given visual field.

Attentional suppression, much like rivalry suppression, even renders stimuli invisible. When attention is directed elsewhere, we hardly perceive what we are looking at; this is known as inattentional blindness (Mack & Rock, 1998; Most et al., 2005). Even salient events such as the appearance of new objects are not detected when attention is directed to a different location. Indeed, the cause of inattentional blindness has been suggested to be attentional suppression (Thakral & Slotnick, 2010). Such findings show that attentional suppression is able to bring the same end result as rivalry suppression: causing stimuli to be invisible.

Such phenomenal similarity between attentional and rivalry suppression is also reflected in their interaction. Attention can influence the rate of dominance changes (Chong, Tadin, & Blake, 2005; Lack, 1978) and the initial dominance of the attended stimulus (Chong & Blake, 2006; Mitchell, Stoner, & Reynolds, 2004) 2 . Furthermore, without attention, the ERP and behavioral signatures demarcating perceptual changes disappear (Brascamp & Blake, 2012; Zhang, Jamison, Engel, He, & He, 2011). A recent study (Ling & Blake, 2012) suggests that attention and rivalry suppression operate via the same computational mechanism of normalization (Reynolds & Heeger, 2009).

Attention and suppression change the perceptual quality of the visual stimuli in opposite ways. Attention enhances the perception of relevant items, making them consciously vivid. Meanwhile, attention filters out other irrelevant items. These unattended stimuli are less processed compared to neutral ones, and they are sometimes even rendered invisible. Similarly, suppression reduces the visibility of the stimuli to the unconscious level.

2Note that attentional suppression plays a more active role than rivalry suppression. Meng & Tong (2004) found that observers showed much weaker attentional control over rivalry alternations than Necker cube alternations.

Neural Correlates of Attention and Suppression: The Fronto-Parietal Network

The commonalities between attention and suppression are also reflected in their neural correlates. The fronto-parietal network is important for attention. Specifically, the network is implicated in orienting attention (Buschman & Millner, 2007; Corbetta & Shulman, 2002; Nobre, 2001). When spatial attention shifts from one visual field to another, the superior parietal cortex shows transient neural activities (Yantis et al., 2002). Duncan (2006) also suggests that activities biased by attention arise from the frontal and parietal cortices. The same network appears to be responsible for various types of attention, regardless of whether they are feature-based (Shulman, 2002) or location-based (Corbetta, 1998).

The fronto-parietal network has also been implicated in triggering state changes in rivalry. Reviews of recent brain-imaging studies (Rees, Kreiman, & Koch, 2002; Sterzer, Kleinschmidt, & Rees, 2009) have viewed the role of fronto-parietal network as initiating perceptual changes in bi-stable figures (but see also Knapen, Brascamp, Pearson, van Ee, & Blake, 2011). Moreover, activities in the right fronto-parietal region were correlated with perceptual transitions in rivalry (Lumer, Friston, & Rees, 1998). Consistent with this finding, rTMS over the right superior parietal cortex reduced dominance durations in rivalry (Carmel et al., 2010), implying that rTMS interfered with maintaining the current state of rivalry.

The parietal cortex appears to initiate shifts of attention (Yantis et al., 2002) and perceptual alternation during rivalry (Carmel et al., 2010). This initiation in turn flows down to content-specific visual areas to modulate the amount of attention and suppression. In both humans (Ruff, Blankenburg, Bjoertomt, Bestmann, Freeman, Haynes, ... & Driver, 2006) and monkeys (Moore & Armstrong, 2003), activities in the early visual cortex were directly influenced by electrical stimulation to the frontal eye fields.

Hierarchical Representation of Attention and Suppression

Attention and suppression initiated from the parietal cortex are hierarchically reflected in visual areas. More specifically, both effects are observed over multiple stages of visual processing with stronger effects towards higher visual areas. We argue that both attention and suppression have greater effects in higher visual areas in order to cope with increased complexity of information (Felleman & Van Essen, 1991; Ungerleider & Mishkin, 1982).

Attentional selection occurs at multiple stages of visual information processing. Attentional effects are observed as early as LGN (O’Connor, Fukui, Pinsk, & Kastner, 2002), consistent with the early selection models of attention (Broadbent, 1982). The effects, however, are more pronounced for successive visual areas along the hierarchy (Kastner, De Weerd, Desimone, & Ungerleider, 1998; Schwartz, Vuilleumier, Hutton, Maravita, Dolan, & Driver, 2005).

The locus of visual selection depends on the perceptual load imposed on the visual system (Lavie, 1995; 2000; Lavie & Cox, 1997; Lavie & Tsal, 1994). More precisely, the extent to which a perceptual task consumes available resources determines how much task-irrelevant, unselected stimuli will be processed. With a high perceptual load, there is not enough capacity to process irrelevant stimuli and selection appears to occur at an early stage. In contrast, when the perceptual load is low, task-irrelevant stimuli will receive enough attentional resources to be processed, in accordance with the late-selection model (Deutsch & Deutsch, 1963). The selection is modulated more by the task load at higher visual areas compared to early visual areas (Schwartz et al., 2005), implying that the complexity of information affects later visual processing more.

Suppression also achieves its goal over multiple stages of visual processing, and the effects become augmented in higher areas. The visibility of an adaptor during rivalry modulated the amount of spiral motion aftereffects (Wiesenfelder & Blake, 1990), whereas it did not affect the aftereffects of linear motion (Lehmkuhle & Fox, 1975, but see also Blake et al., 2006). Because linear motion is mostly processed in early visual areas (Movshon & Newsome, 1992) and spiral motion is mostly processed in higher visual areas such as MST (Duffy & Wurtz, 1991), these results suggest that the depth of suppression becomes larger along the dorsal stream. This trend was confirmed using plaid-pattern-induced motion aftereffects (Van Der Zwan, Wenderoth, & Alais, 1993). Motion aftereffects were reduced with the plaid pattern but not with a component grating as an adaptor.

In the ventral stream, the ERP amplitudes of suppressed stimuli were not reduced in early visual areas (Riggs & Whittle, 1967, but see also Zhang et al., 2011), whereas in higher areas the depth of suppression was larger even to a level corresponding to the physical removal of stimuli (Moradi, Koch, & Shimojo, 2005). Nguyen et al. (2003) investigated the depth of suppression depending on the complexity of stimuli and found that probe detection became progressively more difficult as the complexity of a suppressed stimulus increased. In addition, more neurons in higher visual areas showed the pattern of activities that was correlated with percept changes in rivalry (Leopold & Logothetis, 1996). Again, these results suggest that the depth of suppression becomes deeper in higher areas.

In summary, the effects of attention, originated from the higher information processing stages (Hochstein & Ahissar, 2002), are stronger in higher visual areas (Kastner et al., 1998; Schwartz, 2005) and are observed in multiple stages of visual processing (Broadbent, 1958; Deutsch & Deutsch, 1963; Treisman, 1960). Similarly, the effects of suppression become stronger towards higher areas (Nguyen et al., 2003) and occur in multiple stages of visual processing as well (Blake & Logothetis, 2002; Tong, Meng, & Blake, 2006). In addition, the magnitudes of the two effects are also observed to be in comparable ranges across multiple studies (see Box 2).

3Please note that this examination is not a thorough investigation of the literature by any means. We simply wanted to check the magnitude of both effects in relatively well-matched studies

Early researchers have only noted the similarity between attention and binocular rivalry as aspects of the visual selection mechanism (William James, 1890; von Helmholtz, 1924). Here, we review recent experimental evidence of various similarities and make a connection between attention and rivalry suppression via consciousness. The connection is further supported by the similar fates of unattended information and suppressed information: both attention and rivalry suppression can render stimuli invisible and they even interact, indicating that they are based on the common mechanism (normalization). The neural correlates of attention and suppression also share the same origin: the fronto-parietal network. Finally, both effects become more pronounced in higher visual areas to serve the same purpose of increasing selection efficiency given more complex stimuli.

Despite these similarities, attention and suppression have not been proposed to serve a common goal in the visual system. Recent studies suggest, however, that suppression as well as attention work in order to achieve an economical representation of a complex scene. More specifically, the visual system uses suppression to retain possibly necessary information without conscious effort, as invisible items can still contribute to the visual working memory (Soto, Mäntylä, & Silvanto, 2011). Moreover, a transient signal in the suppressed eye—an indicator of a new and potentially important input—usually breaks suppression (Blake, Westendorf, & Fox, 1990). Attention may bring the suppressed information back to consciousness. Although invisible high-level stimuli such as faces do not usually produce aftereffects (Moradi et al., 2005), they can if they are attended (Shin, Stolte, & Chong, 2009). In addition, it has been proposed that visual features could be unconsciously bound (Lin & He, 2009), although the binding is fragile unlike the conscious one. Therefore, it is plausible that invisible features under suppression are weakly bound and promptly used when attended.

We propose that both attention and suppression operate to overcome the limited capacity of the visual system: attention selects relevant information and suppression keeps potentially relevant (currently irrelevant) information without additional costs. As the visual system processes more complex information in higher areas, the burden of retaining the information increases because more refined and complex representation is required. Thus, attention helps the visual system to reduce the burden by augmenting its effects and suppression is able to do the similar job by increasing the depth of suppression.