The objective of this study is to explain the differences between ‘-asŏ/-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko,’1 two clausal connective endings which express temporal relationships in the Korean language. These two connectives, ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko,’ have a variety of uses, both functioning to show temporal sequence. Studies have been conducted on the differences between these two connectives but without providing sufficient explanations.

In second or foreign language education, it is important for the teacher and student to be able to explain the uses of the target language. The set of grammar rules that are easily understood by learners is called “instructional grammar,” and it is from this perspective that the differences between ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko,’ will be analyzed in in this study.

It is usually the case that uses of a single grammatical item are greatly varied and complex. Therefore, this study first makes observations of the conditions for the use of ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko’ before giving clear explanations of their different uses.

This study is conducted in the following order. The following section examines the ways the grammar texts and dictionaries have described the differences between the clausal connectives of temporal sequence ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko.’ Section 3 examines the actual uses of ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko’ and offers a way to explain the differences after close analysis. The conclusion will summarize the findings of this study.

1‘-asŏ’ and ‘-ŏsŏ’ are allomorphs of the same morpheme, but this study employs ‘–ŏsŏ’ for convenience. While the Korean clausal connective ‘ –고 ’ would be ‘–go’ after a vowel according to M-R romanization, ‘–ko’ is employed in the study. This decision reflects the limitations of using a transcription system of romanization in an article where a transliteration system might be preferable.

2. PREVIOUS DISCUSSIONS ON ‘-?S?’ AND ‘-KO’

Grammar texts and dictionaries currently in use describe differences between the temporal connectives endings as follows. The National Institute of the Korean Language (2005a, 127–128) lists three differences between ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko’: First, it points to the difference that exists in the “correlation” between the preceding clause and the following clause. When the correlation is close, ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used; when it is not close, ‘-ko’ is used. Second, if an element in the first part of the clause can be repeated in the second part, excepting the subject, ‘-ŏsŏ’ is to be used; in other cases, ‘-ko’ is to be used. This is a more concrete means to show the aforesaid relation. Third, ‘-ko’ is used when one action is completed before another activity occurs while ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used when the first activity continues as the next activity occurs.

The National Institute of the Korean Language (2005b, 530) also states that ‘-ŏsŏ’ is commonly used when there is a close connection between the first and following activities whereas ‘-ko’ is used to express a sequential relation without regard to the connection between the first activity and the following activity.

According to Yeon & Brown (2011, 261, 285), ‘-ŏsŏ’ denotes, as a “sequential marker”, that the second clause takes place in a state or in a position created by the first clause. The events in the two clauses have to be tightly linked. But ‘-ko’ lists actions in their chronological sequence.

Concerning the difference between ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko,’ Cho et al. (2000a, 254; 2000b, 85) mention ‘-ŏsŏ’ connects two sequential events, with the second event always a result of the first. Even when the first event does not cause the second, it is a precondition for the second event. In contrast, the basic meaning of ‘-ko’ which is also used to indicate a sequence of actions or events, is simply to list two or more events, and there is no implication that the first event leads to the second.

Heo et al. (2005, 300-301) explain that ‘-ko’ is used when the first activity is completely finished before the next activity occurs while ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used when the first activity has occurred but its effect continues as the next activity occurs. They further explain that ‘-ko’ is commonly used after a transitive verb while ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used after an intransitive verb. However, ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used when the predicates of the previous and following clauses take the same speech element. They explain the uses of ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko’ with the concept of “direct correlation,” saying that ‘-ŏsŏ’ possesses correlation while ‘-ko’ does not. That is, “direct correlation” indicates that a connection is made between the activities in the preceding and following clauses of a sentence.

In any case, the differences described in the above sources can be summarized as follows: ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used when the preceding and following activities are closely connected, where this connection is variously called “(direct) correlation,” or “connection.” As can be surmised, however, there are many exceptions to this kind of explanation. The following section takes a closer look at these exceptions.

3. ANALYSIS OF DIFFERENCES BETWEEN ‘-?S?’ AND ‘-KO’

The National Institute of the Korean Language (2005a; 2005b) adopts the concept of “correlation” to establish the differences between ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko.’

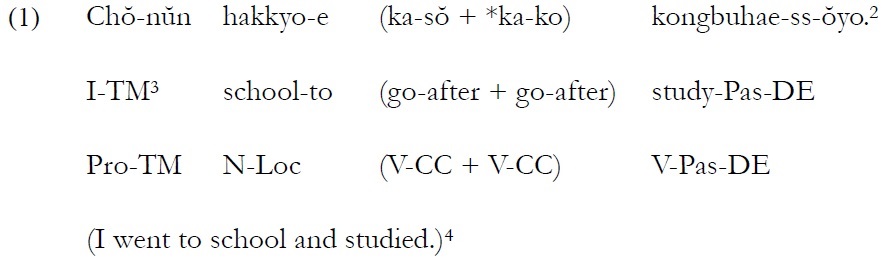

Let’s examine the following examples.

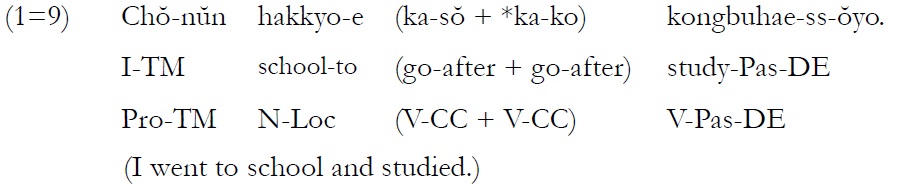

In (1) above, if going to school in the first clause and studying in the following clause are connected by the condition “must go to school in order to study,” it can be said that a correlation exists between the preceding and following clauses. It then follows that it is possible to use ‘-ŏsŏ’ but not ‘-ko.’ Let’s take a look at another example.

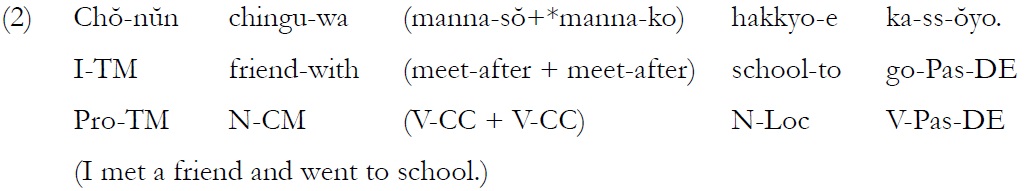

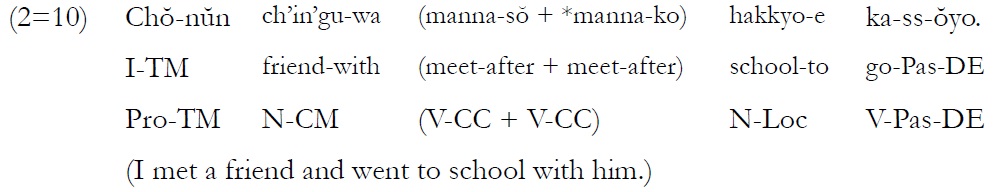

In (2) above, the actions of meeting a friend and of going to school do not seem to have a necessary correlation. That is, going to school does not require meeting a friend. Nevertheless, ‘-ŏsŏ,’ not ‘-ko,’ should be used in sentence (2). It is thus problematic to explain the difference between ‘-ŏsŏ,’ and ‘-ko’ through the concept of correlation only, and without giving a clear definition of this “correlation.”

Many people may think that going to school is necessary for studying but since this is not always a requirement, it cannot be argued that a correlation between the preceding and following clauses exists. This applies also to example sentence (2). Though there may be exceptions, most people will not think it necessary to meet a friend to go to school, and thus there can be no correlation between the preceding and following clauses. Therefore, it is problematic to try to explain the different uses of ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko’ through the idea of correlation.

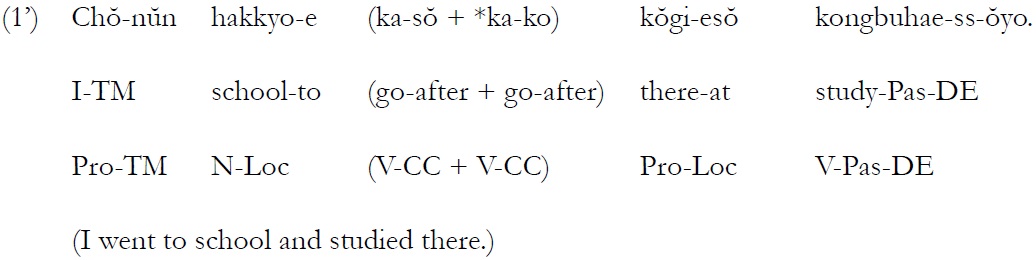

Heo et al. (2005, 300–301) explain that it is possible to use ‘-ŏsŏ’ but not ‘-ko’ in sentences (1) and (2) by claiming that ‘-ko’ is used only when the preceding action is fully completed before the following action occurs but that ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used when the results of an activity that occurs in the preceding clause continues even as the next activity starts to occur.5 As such, the result of having gone to school in (1) and the result of having met a friend in (2) can be seen to continue in the next activity so that (1’) and (2’) below are made possible.

The ‘-ŏsŏ’ in (1’) is used in the adverbial “to school” to indicate location in the first clause and also to indicate “at school” in the following clause. This is not possible with ‘-ko.’6 Similarly, the ‘-ŏsŏ’ in (2’) is used in both “chingu-wa (with my friend)” in the preceding clause and in “kŭ-wa (with him)” in the following clause. Again, this is not possible with ‘-ko.’ Thus, both examples (1) and (2) illustrate that it is not possible to use ‘-ŏsŏ’ but not ‘-ko’ in these situations.

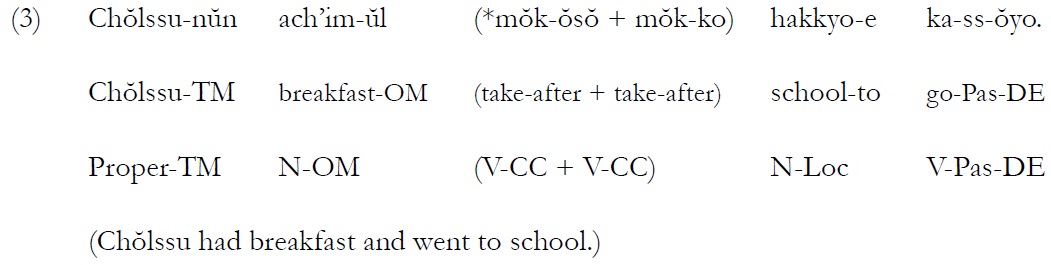

Let us take a look at another example.

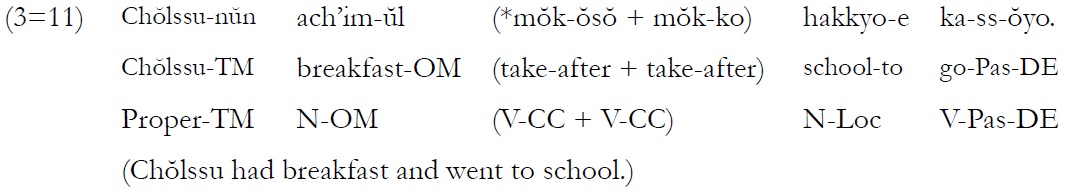

It is not necessary to eat before going to school so sentence (3) does not possess correlation, but it can be said that the result of the action in the preceding clause carried into the following action. Thus, it is not possible to deduce whether ‘-ŏsŏ’ or ‘-ko’ is correct; however, in actual usage, ‘-ŏsŏ’ is possible but ‘-ko’ is not. Thus, Heo et al. (2005, 300–301) also cannot sufficiently explain the possible use of ‘-ko’ in example (3).

The National Institute of the Korean Language (2005a, 127–128) states that ‘-ŏsŏ’ is to be used when an element in the preceding clause, excepting the subject, can be used again in the following clause. When this is not possible, ‘-ko’ is to be used, in which case it indicates more concretely the correlation of ‘-ŏsŏ.’ Heo et al. (2005, 300–301) generally supports using ‘-ko’ after transitive verbs taking objects and using ‘-ŏsŏ’ after an intransitive verb. When the predicates of the preceding and following sentences take the same speech element, they indicate using ‘-ŏsŏ’ but ‘-ko’ is to be used when the first action is completely finished before the next action takes place. But since ‘-ŏsŏ’ can be used when the result of the original activity continues after the completion of the first activity into the following activity, it is discussed in the context of “direct correlation.” In other words, when an element in the preceding clause is repeated in the following clause, “correlation” is said to exist.

Next, let us examine a situation where a transitive or intransitive verb appears in the preceding clause with ‘-ŏsŏ’ or ‘-ko.’

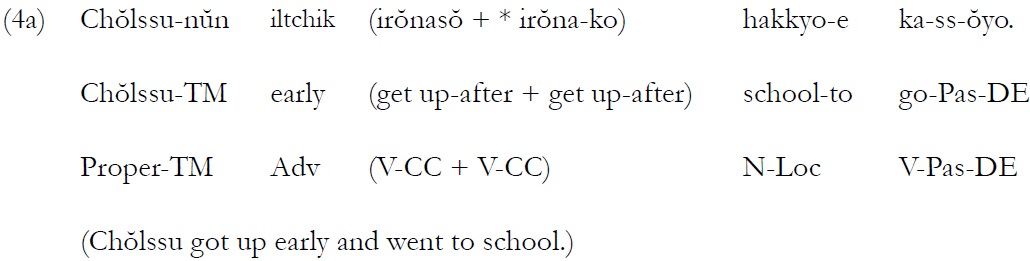

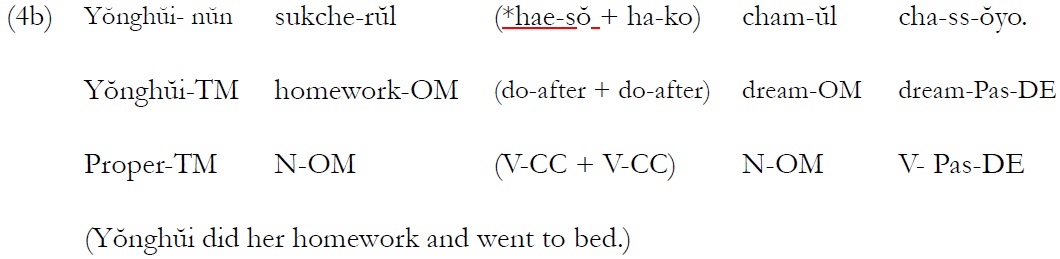

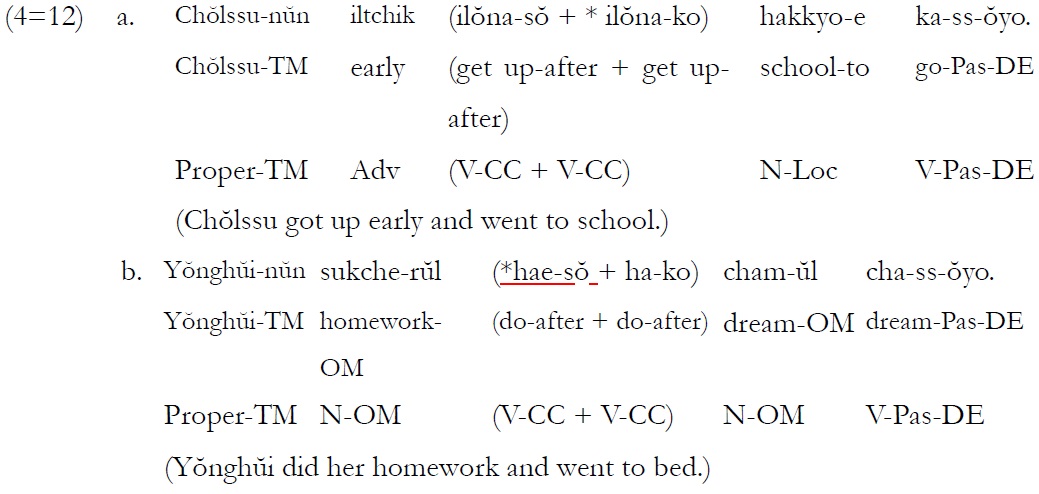

In (4a), it is possible to use ‘-ŏsŏ’ since the preceding clauses contains an intransitive verb. However, it is not possible to use ‘-ko’ in this case. On the other hand, only ‘-ko’ is possible when the preceding clause contains a transitive verb whereas it is not possible to use ‘-ŏsŏ.’ The use of ‘-ŏsŏ’ however, is not because of the intransitive verb in the preceding clause nor is ‘-ko’ used because of the transitive verb in the preceding clause. According to Heo et al. (2005, 300-301), ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used because the result of the action in (4a) continues during the action of “going to school” in the following clause; that is, the connective ending is used because it is not possible to go to school without getting up. In a sense, it can be said that there is a correlation between the preceding and following clauses of (4b), or of having to do homework in order to sleep. Thus, there is a correlation and that the result of having done the homework continues in the action of sleeping. It then follows, according to Heo et al. (2005, 300-301), that while ‘-ŏsŏ’ is the proper choice, ‘-ko’ must be used in its place. Thus, the assertion made by Heo et al. (2005, 300–301) for (4b) is not justified.

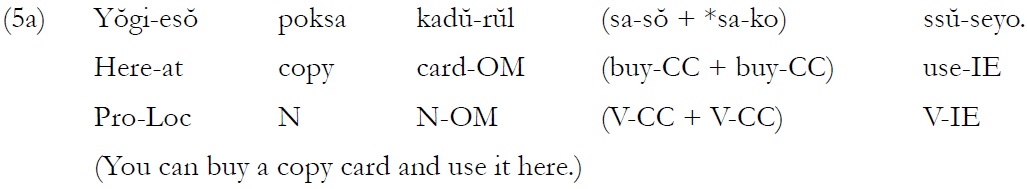

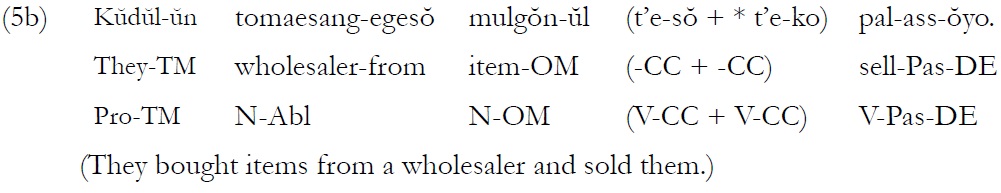

On the other hand, there are instances where ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used in place of ‘-ko’ even though the verb is transitive in the first clause. The following are such examples.

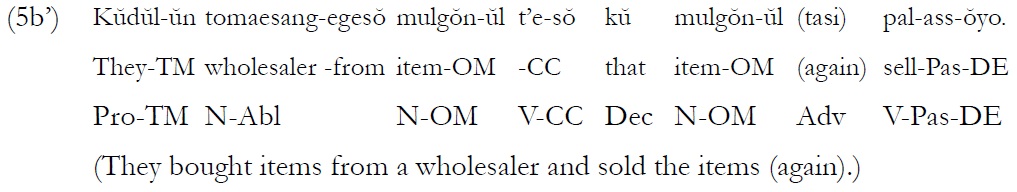

In (5a’), the object in the first clause is repeated in the following clause, expressing the connection between the preceding and following clauses, the connection between “buying” and “using” the copy card. That is, the result of the action of buying the copy card continues in the following action of using the copy card. These two conditions indicate the existence of a “(direct) correlation” between the first and second clauses, thereby establishing that ‘-ko’ is not possible while ‘-ŏsŏ’ is possible in (5a). Furthermore, this confirms that the common explanation is still acceptable in a situation like (5a). The same applies to (5b). Since you cannot sell items without first obtaining them, or since the result of the action in the first clause continues to have an effect on the next clause, ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used. As in (5a’), the object can be complemented as in (5b’), showing that the result in the preceding clause continues into the action of the following clause. It follows that the commonly accepted explanation stands for the situation in (5b) as well.

There are situations where both ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko’ are acceptable.7

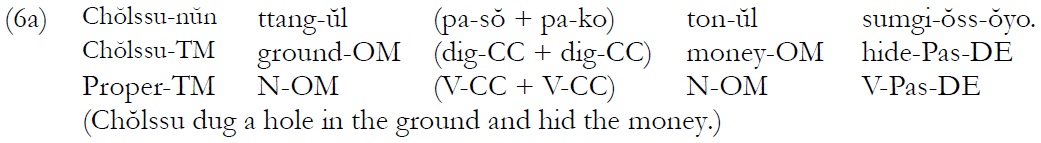

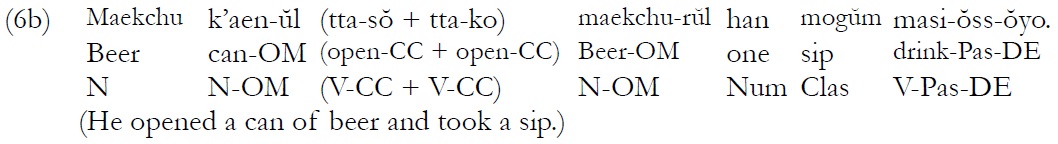

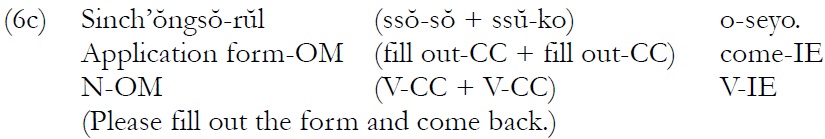

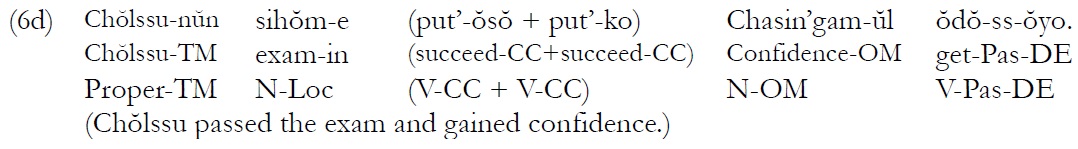

In the examples in (6), both ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko’ can be used. (6a), (6b), and (6c) are examples of first clauses with transitive verbs while (6d) is an example with an intransitive verb.

In the case of (6a), can it be said that there is a connection between digging a hole and hiding the money? Does the result of the action in the first clause continue in the second following clause? In other words, does the result of digging a hole continue to have effect in the act of hiding the money? If what is usually called “correlation” exists in (6a), only ‘-ŏsŏ’ should be possible. However, both ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko’ are possible here.8

Thus, the concept of “correlation” cannot explain the differences between the two connective endings in this case. It is this article’s assertion that a different explanation is needed. The following is offered as a better way to explain the differences in the uses of the connectives ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko.’ The connective ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used when the result of the action in the preceding clause continues in the action of the following clause, establishing a pragmatic connection with the following action. This contrasts with the connective ‘-ko’ which is used when no pragmatic connection takes place regardless of the continuation of the result of the action in the preceding clause in the following clause.

Forming a pragmatic connection here refers to a situation where the speaker recognizes the need for a prior action to take place before another action can be taken. That is, a prior action is not required for a following action from the perspective of logic but it is required because the speaker understands the necessity of one action before another following action can take place. It is for this particular situation that this study applies the term “pragmatic relevance”.

Let us look at (6a) once more. If we accept that there is a close pragmatic connection between the act of digging a hole and hiding the money or that a hole must be dug before money can be hidden, the speaker must use the connective ‘-ŏsŏ.’ On the other hand, if the speaker considers the actions “digging a hole” and “hiding the money” as unconnected activities, or that there is no reason to dig a hole in order to hide the money, the speaker will opt to use ‘-ko’ instead.

The same applies to (6b): from the perspective of pragmatics, slight differences can be observed in sentences using the connectives ‘-ŏsŏ’ or ‘-ko.’ If the speaker believes that there is pragmatic relevance between opening a can of beer and drinking beer exists, or that a can of beer must be opened before it can be drunk, then the speaker uses the connective ‘-ŏsŏ.’ However, if the speaker does not feel that a close correlation between opening a can of beer and drinking beer, or considers that the action of opening a can of beer and drinking beer are two independent acts, then the speaker will opt to use ‘-ko’ instead.

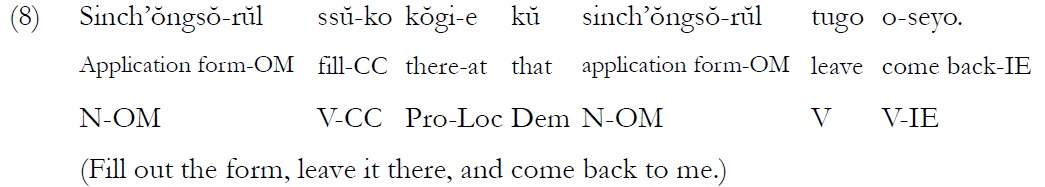

In sentence (6c), a clear difference in meaning between the sentences using ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko’ is discernible. If ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used, the sentence carries the meaning that the applicant must fill out the form and take it to the speaker. In other words, the result of the action in the first clause continues into the next, making a pragmatic connection. Thus, the sentence in (6c) can be paraphrased as (7) below.

On the other hand, if this sentence uses the connective ‘-ko’ then the meaning changes to suggest that the applicant can fill out the form but may go back to the speaker without the form. In other words, the result of the prior action does not make a pragmatic connection with the next action. Thus, the sentence can be rewritten as follows.

In example (6d), both ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko’ connectives can be used. If the speaker considers that there is a close pragmatic connection between “taking a test” and “gaining confidence,” he will use ‘-ŏsŏ’ but will use ‘-ko’ if he sees no pragmatic connection between taking a test and gaining confidence.9

It would be beneficial at this point to review the examples discussed above by considering the differences in the practical usage of the ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko’ connective endings.

First, in (9) above, we can observe that the action of “going to school” continues to have effect on the action of “studying”. The speaker also obviously considers it necessary to go to school in order to study. In other words, a “pragmatic relevance” is established between the preceding and following clauses. This is why ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used instead of ‘-ko’ in this situation.

This conclusion applies also to sentence (10) above. It can be said that because the speaker met his friend and went to school with the friend, the result of the act of meeting a friend continues to the act of going to school. While logically one does not have to meet a friend in order to go to school, the speaker here considers that the action in the second clause requires the action in the first clause. That is, the preceding and following clauses establish a pragmatic relevance so that the connective ‘-ŏsŏ’ is chosen over the connective ‘-ko.’ The following example will clarify the above discussion.

Example (10’) is similar to (10) but “chingu-wa (with friend)” is changed to “chingu-rŭl (friend).”10 The meaning is changed from “going to school with a friend” to simply “meeting a friend”. The sentence which uses “-ko” seems naturally to imply a temporal sequence,11 the reason being that using “chingurŭl (friend)” rather than “chingu-wa (with friend),” or as object rather than adverbial, eliminates the idea of accompaniment so that the sentence comes to have the meaning of “I met my friend and I went to school without my friend.” That is, the action of “meeting a friend” in the first clause does not imply “going to school” or establish a pragmatic relevance with “going to school.” Therefore, ‘-ŏsŏ’ cannot be used in this situation12 whereas ‘-ko’ can be used.

If we examine example (11), we can observe that the result of the action of eating continues in the following action of going to school. But as discussed previously, ‘-ko’ can be used without regard to whether or not the consequence of the action in the first clause continues into the concluding clause if a pragmatic relevance is not established between the two clauses. But a pragmatic relevance does not exist between the two clauses in (11). That is, the speaker of this sentence does not believe that one has to eat in order to go to school. That is the reason that ‘-ko’ is used and not ‘-ŏsŏ.’

In example sentence (12a), the action of getting up has consequence on the action of going to school. We can then observe that the speaker considers it necessary to get up early in order to go to school. In other words, a pragmatic relevance is established between the two clauses. Therefore, ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used here rather than ‘-ko.’

On the other hand, the result of the action of doing homework in the first clause in (12b) can be said to continue in the second clause. However, a pragmatic correlation is not present between the two clauses in this example. That is, the speaker does not think it necessary to do homework before going to bed. This is why the ending ‘-ko’ is used here rather than the ending ‘-ŏsŏ.’

2* indicates the ungrammatical form of the Korean sentence. 3The following abbreviations are used to show Korean grammatical morphemes: Abl(Ablative Marker), Adv(Adverb), CC(Clausal Connective), Clas(Classifier), CM(Comitative Marker), Comp (Complementizer), DE(Declarative Ending), Dem(Demonstrative Determiner), Det(Determinant Ending), IE(Imperative Ending), Loc(Locative Marker), Num(Numeral Determiner), OM(Object Marker), Pas(Past), N(Noun), Pro(Pronoun), Proper(Proper Noun), TM(Topic Marker), V(Verb). 4The English example sentence is not an exact translation but a close reflection of the correctly written Korean sentence. Rather, it is closer to the sentence containing the ‘-ko’ construction. The sentence containing ‘-ŏsŏ’ may be translated as “I went to school to study.” However, the act of studying may or may not take place according to this English sentence. Therefore, the English translation reflects the meaning but is not an accurate equivalent of the Korean sentence. Other example sentences which follow may also fall under this limitation. 5The National Institute of the Korean Language (2005a, 127–128) states that ‘-ko’ is used when the result of one action is completed before another action occurs while ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used when an action occurs while a prior action is still occurring. This explanation needs to be qualified as ‘-ŏsŏ’ is possible not when the following action occurs while the first action continues but when the result of the first action is continuing when the next action occurs. 6This has already been established by the National Institute of the Korean Language (2005a, 127– 128), Yeon & Brown (2011, 261, 285), Cho et al. (2000a, 254; 2000b, 85) and by Heo et al. (2005, 300–301). 7It has been pointed out that while it should be possible to use both ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko’ in all cases, there are many instances when only one of the two connectives is possible. However, it is possible to use both ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko’ in all cases if the pragmatic situations are indicated with appropriate suppositions. 8To the assertion made that a sentence using ‘-ko’ as in (6a) can have both the meaning of “conditional temporal sequence” and of “simple temporal sequence,” this article argues that a sentence using ‘-ko’ as in (6a) can possess only the meaning of simple temporal sequence. 9It can be observed that the clausal connectives ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko’ in (6d) are employed to show cause and effect rather than temporal sequence. While with ‘-ŏsŏ,’ temporal sequence or causeeffect is classified separately as having comparable status, with ‘-ko,’ the temporal sequence and cause-effect relations are not distinguished but rather included in the former. This is a matter that requires further discussion (Cf. Pak 2012a, 2012b, 2013a, 2013b). 10As pointed out in a review of this article, ‘kach’i’ (together) may be used with ‘-ŏsŏ’ in (10’). However, a sentence without ‘kach’i’ (together) is not possible. On the other hand, while it may appear implausible to have the meaning of temporal sequence when using ‘–ko’ in (10’), this article considers this to be evident. This has been proven by many native speakers of Korean. 11In this case, a pause between the preceding and following clauses makes the sentence more natural, and the sentence can be paraphrased as follows: 12It is possible to have a sentence with ‘-ŏsŏ’ in a sentence like (10’) in which case ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used to indicate a cause-effect relationship. In that case, a sentence with ‘-ŏsŏ’ can be paraphrased as follows:

This study focused on analyzing ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko,’ two connective endings of temporal sequence between clauses. Previous studies have explained that ‘-ko’ is used after a transitive verb that takes an object while ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used after an intransitive verb but also that ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used when the predicates of preceding and following clauses, including the object, takes the same speech element. And while ‘-ko’ is used when the first action is completely finished before the next action can occur, ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used when an action has occurred in the first clause but the result of that action continues even as the following action occurs. These discussions, however, do not sufficiently explain the different uses of ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko’ nor do they address the numerous exceptions.

This study has attempted to analyze and supplement previous studies by suggesting that the differences in the uses of ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko,’ can be effectively explained as follows: ‘-ŏsŏ’ is used when the result of the action in the preceding clause continues during the action in the following clause and when pragmatic relevance is established. On the other hand, ‘-ko,’ is used when pragmatic relevance is not established whether or not the result of the action in the first clause continues to have effect on the following clause.

This study has explained the use of ‘-ŏsŏ’ and ‘-ko’ with special emphasis on pragmatic relevance, which is an attempt to base the discussion of differences in the usage of Korean clausal connective endings on discourse situations. It is only when analysis becomes rigorous in this way that discourse grammar for Korean clausal connectives can become more firmly established.