What is the relationship between political generation and foreign policy? By examining Korea’s sudden and sharp foreign policy change during the Roh Moo-hyun government, 2003-2007, in this article I show that when a political generation with distinctive emotions and preferences rises in power, it can have a significant impact on foreign policy. Despite the alliance ties with the United States and North Korea’s continuing development of nuclear weapons, the Roh government sought to redefine relations with the former, while deepening economic and political engagement with the latter to an unprecedented extent. I argue that the rise of what I call the “democratization generation” in Korean politics is the key to understanding why Korea’s foreign policy changed in this period. The findings of the paper suggest that a salient political generation is indeed an important domestic source of foreign policy preferences and change.

This article investigates the relationship between political generation and foreign policy using the experiential model of generation. It demonstrates how the emergence of a political generation through a significant historical event can be a major source of foreign policy preferences and lead to foreign policy changes. In particular, I analyze South Korea’s foreign policy change during the Roh Moo-hyun administration (2003-2007).

The Republic of Korea (ROK; South Korea)1) during the Roh administration is a good case study because its security and foreign policy underwent sudden and significant changes in the two most important aspects of its external relations, namely, its US and North Korea policies. The Roh administration sought greater independence from the United States in determining national security and foreign policy and aimed to revise various aspects of the ROKUS alliance, departing from the traditional emphasis on close alliance ties. At the same time, the administration engaged with North Korea to an unprecedented extent, despite increased military threat from the North due to the latter’s renewed interest in developing nuclear weapons. Both the official economic aid to the North and inter-Korean exchanges increased dramatically, even if doing so put South Korea in policy discord with the United States and weakened close trilateral cooperation with the United States and Japan.

Why did Korea, a long-time ally of the United States, suddenly seek greater independence from its patron, and what explains its unprecedented level of engagement with North Korea despite the latter’s increased military threat? The existing explanations for South Korea’s foreign policy change during this period focus on structural and material factors such as the end of the Cold War and enhanced material power of South Korea. These explanations, however, fail to account for the

I support my argument with the analysis of the 2005 East Asian Institute (EAI) elite survey. While not representative, the survey is the first of its kind in Korea measuring perceptions and preferences of what can be described as Korea’s sociopolitical elite on a number of important foreign policy issues. Hence it has a distinctive advantage over public opinion surveys because the sociopolitical elite have a greater degree of influence over policymaking. I supplement the survey analysis with my own interview data. The regression analysis of the survey shows a significant generational effect on key policies even after controlling for a number of factors such as political party, income, gender, and education.

The argument and findings of the article shed new light on understanding Korean politics and future trajectory of its foreign policy. Generational differences and views were an important domestic source of South Korea’s foreign policy change during the Roh administration. Furthermore, the politics of generational differences, which came to the fore during the Roh presidency, are not a matter of the past in Korean society. As the sinking of the ROK navy vessel

The article is organized as follows. First, I describe the foreign policy changes of Korea during the Roh administration. The next section reviews the experiential model of generational differences, followed by a discussion of how a salient political generation with distinctive emotions and policy preferences emerged through the historical experience of the democratization movement. Analysis of the EAI survey follows, showing generational effects on emotions and foreign policy preferences with regard to the United States and North Korea. I conclude with discussion on the implications of the article’s findings for future Korean politics and foreign policy.

1)Note that in this article “Korea” is used interchangeably with “South Korea.”

Ⅱ. South Korea’s Foreign Policy Changes from 2003 to 2007

The self-termed ‘Participatory Government,’ the Roh administration wanted to enhance South Korea’s international role while maintaining peace and stability on the Korean peninsula and in East Asia.2) To achieve this objective, the administration sought to resolve the North Korean nuclear problem through dialogue and cooperation, and alter the ROK-US relations in a way that reflects Korea’s enhanced material capabilities and gives Korea a greater voice and independence in the determination of its own national security matters.3)

1. Transforming the ROK-US Relations

Having come into office with strong support from the anti-American and progressive segments of Korean society and in the social context of increased anti-US sentiments,4) there were voices within the Blue House and the ruling Uri Party right from the beginning that pushed for a redefinition of the ROKUS relations. They argued that the ROK-US alliance should adjust to reflect the enhanced economic, political, and military capabilities of South Korea as well as the new international environment of the end of the Cold War. The most indicative of Roh’s desire to achieve greater independence is reflected clearly in his 2004 speech announcing, “Korea will play the role of a balancer, not only on the Korean peninsula, but throughout Northeast Asia.”5) The implication of this new role conception was clear: South Korea should mediate and balance between North Korea and the United States in a narrow sense, and between China and the United States in a larger context. Its logical consequence was that Korea’s role as a US ally would assume secondary importance or even gradually disappear.

The term

The notion of

Based on the

To be accurate, not all the policy changes in the ROK-US relationship came from the Roh government. The Washington’s global strategy was also changing at the same time with new emphasis on the war against terrorism, and significantly affected US relations with its alliance partners around the world, including Korea. According to several senior officials in Korea’s foreign and defense ministries, the relocation of the US forces in Korea was the direct result of the change in the United States’ global strategy due to the Iraq War, while the issue of missions transfer reflected Korea’s desire to assume leadership in its national defense.11) Another defense ministry official suggested that the Roh government took advantage of the situation the United States was in, and hurried the process of the FOTA discussions so that during his presidential term he could take the discussion so far down the road that the future government would not be able to reverse course. What is beyond doubt, however, is that the Roh administration desired to redefine the ROKUS relations so as to assume for Korea greater independence from the United States in its national security and foreign policy matters.

2. Accelerating Inter-Korean Relations

In contrast to the cooling-down of ROK-US relations, inter-Korean relations saw something of a renaissance during Roh’s term in office. The North Korea policy of the Roh administration is called “Peace and Prosperity Policy” (

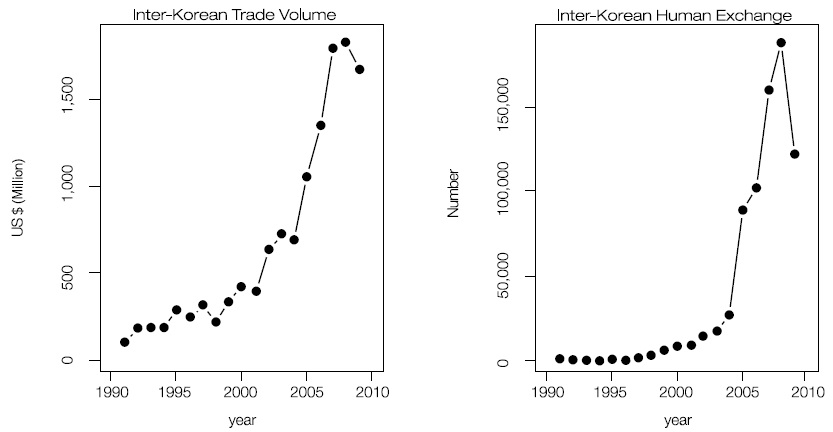

Figure 1 shows the trends in the inter-Korean trade volumes and human exchanges since 1990. Since 2003 when Roh took office, the trend has accelerated at an exponential rate. In 2003, the total inter-Korean trade volume was about 720 million, whereas in 2007 it had grown to be approximately 1.8 billion dollars, an increase of about 2.5 times in four years. The South became the second largest trading partner of the North (after China), and the North’s trade volume with the South amounted to one quarter of its total trade.

Human interactions between the two Koreas kept pace with the growth in inter-Korean economic trade. Up until the early 2000s the inter-Korean human exchanges had been rather infrequent. During the Roh presidency, however, the human exchanges increased exponentially. In 2003 about 16,000 people crossed the 38th parallel to visit North Korea, but the number reached approximately 160,000 in 2007, a tenfold increase.

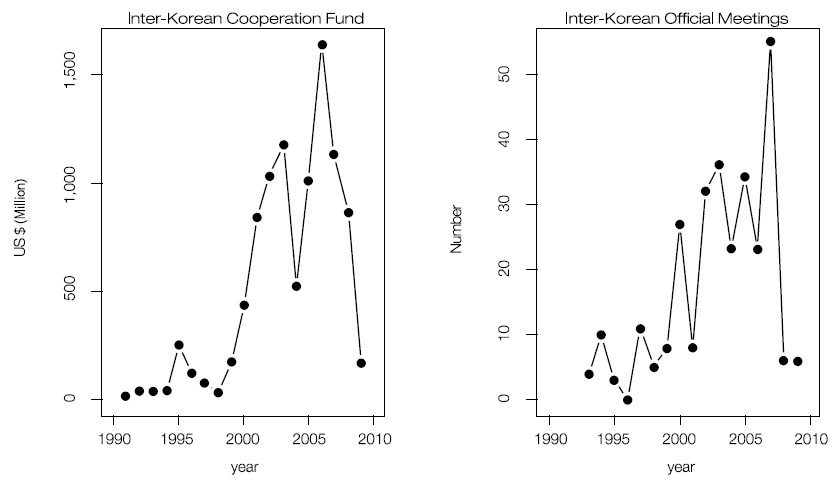

Figure 2 presents the annual amount of the Inter-Korean Cooperation Fund and the number of official meetings held between the two Koreas. Though more fluctuating than in the previous graphs, both the fund and meetings increased during the Roh presidency. The average annual amount contributed to the cooperation fund during Roh’s presidency was more than twice the amount during the Kim Dae-jung administration. The official meetings between the two Koreas also became more frequent during the Roh administration, reaching its peak in 2007 with fifty-five meetings. Both Figures 1 and 2 show clear evidence that inter-Korean relations improved dramatically during the Roh administration.

The administration’s conciliatory approach to the North is also reflected in its voting behavior in the United Nations (UN) on North Korea’s human rights problem as well as official aid to North Korea. There were five UN human rights resolutions relating to North Korea during the Roh presidency, and the Korean government chose to abstain four times. The government casted a “yes” vote only once in 2006 under increasing pressure from domestic NGOs and because of Ban Ki-moon’s candidacy for the UN Secretary-General.14) It also provided North Korea with an average annual amount of official aid exceeding USD 280 million, which is more than twice the amount provided to the North under the Kim Dae-jung administration.

When it came to dealing with the North Korean nuclear problem, the Roh government adopted the ‘carrot’ rather that ‘stick’ approach. Even when North Korea threatened to suspend its participation in the Six-Party Talks (6PT) in February 2005, the Roh government still announced in June its intention to supply North Korea with 2 million KW of electricity. Its ardent adherence to engagement with the North resulted in booming inter-Korean economic and human exchanges despite the second nuclear crisis on the peninsula. This trend contrasts sharply with the revision of ROK-US relations in a more

2)The National Security Council (NSC) of ROK, Peace, Prosperity and National Security: National Security Strategy of the Republic of Korea (Seoul: NSC, 2004). 3)This is not to say that the Roh administration did not value Korea’s ties with the United States. But when siding with the United States was perceived to be against ROK’s national interests, as was the case in dealing with North Korea, it did not hesitate to deviate from the US position. See for more details Dong-Jun Hwang, The National Defense Vision of the Participatory Government and Appropriate National Defense Budget (Seoul: ROK National Defense Institute, 2005). 4)In 2002 two Korean school girls were run over by US armored vehicles. As a result, anti-US sentiments were high at the time of Roh’s inauguration. The incident led to an emotionally-charged public demand to revise the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) between ROK and the United States. The upsurge of anti-American sentiments caused concern among the US Korean watchers as well as policymakers in both countries. See David Kang and Victor Cha, “The Korea Crisis,” Foreign Policy 136 (May-June 2003); Seung-hwan Kim, “Anti-Americanism in Korea,” Washington Quarterly 26-1 (Winter 2002-2003). 5)Roh Moo-hyun, Speech Collection Part II (2004.2.1 to 2005.1.31) (Seoul: Government Information Agency, 2005), pp. 120-122. 6)Ibid., p. 133. 7)Dong-jun Hwang, op. cit., p. 41. 8)Roh Moo-hyun, Speech Collection Part II and Part III (2004.2.1 to 2005.1.31) (Seoul: Government Information Agency, 2005 and 2007), pp. 120-122. 9)Dong-jun Hwang, op. cit., p. 26. 10)See the Presidential Commission on Policy Planning, “Toward a New Approach of the Participatory Government’s Unification, Foreign Policy, National Security Policies Based on Analysis and Achievements” (Seoul: 2005). 11)Author’s interviews in April 2009 and March 2010. 12)Ministry of Unification (MOU), The Three Years of the Participatory Government: Results of ‘Peace and Prosperity Policy’ (Seoul: MOU, 2006). 13)Key-young Son, South Korean Engagement Policies and North Korea: Identities, Norms and the Sunshine Policy (New York: Routledge, 2006), pp. 49-52. 14)Government Information Agency of ROK, The White Book for State Affairs (Seoul: GIA, 2008), p. 398.

Ⅲ. The Experiential Model of Political Generation

In explaining sociopolitical continuity and change, scholars have argued that in the absence of major historical and political events, we are likely to observe a stable society in which the equilibrium of social roles is maintained and the political lessons of childhood are reinforced through both official and social education. On the other hand, the occurrence of major historical and political events is likely to result in a political disjuncture and intergenerational discontinuity often characterized by an abrupt and often violent transformation of society. In such case, discontinuities between childhood socialization and adult experience provide more scope for resocialization of political attitudes and values. Because this article concerns itself with sociopolitical change, I use the experiential model of political generation to explain Korea’s foreign policy change between 2003 and 2007.

Mannheim’s experiential theory argues that generational differences emerge during early adulthood, what he called the ‘formative years’ of 18 to 25 years, through major historical and political events.15) Mannheim called generations as sociopolitical “entelechies,” embodying enduring social groupings, and defined them as groups of individuals who are “endowed ⋯ with a common location in the historical dimension of the social process.”16) Sigmund Neumann speaks of the gerontocracies that marked European leadership after World War I.17) Crittenden speaks of the impact of the Great Depression and the New Deal on party affiliation in United States. 18) Because experience is the primary socializing factor, the size of generation could vary, and so can the salience of generational features, as one generation could be politically active, while another might not. The experiential model also states that once formed, generational views and attitudes are deeply ingrained and are likely to remain relatively undisturbed throughout the rest of one’s life.19)

One critical issue for the experiential theory concerns determining what historical and political events can qualify as transformative or socializing events.20) The lack of a rigorous definition of what event qualifies as transformative leads to an indiscriminate usage of the concept, as suggested by such terms as the ‘MTV generation,’ the ‘twenty-something generation,’ and ‘generation X’.21) However, generational differences as a form of social cleavage are not as prevalent or salient as other cleavages such as class, race, and ethnicity. This suggests that only certain events can lead to the formation of salient generations. As Schuman and Scott aptly note, “only where events occur in such a manner to demarcate a cohort in terms of its ‘historical-social’ consciousness should we speak of a true generation.”22)

What historical events can lead to the formation of a different historicalsocial consciousness? Although it is difficult to a

Once a generation is formed through a transformative event, there are two ways that the generation can bring about sociopolitical changes. The first is through social turnover. That is, the members of one salient generation may die, and are replaced by the members of another salient, and younger, generation. The members of the younger generation may effect change, as their views, attitudes, and beliefs become more dominant in society. The second is through political turnover. When certain members of a new generation may occupy key positions of power, they can effect policy changes. Such change may not be consistent with the dominant attitudes of the populace, but is likely to reflect the preferences of the generation to which those members belong.

15)Norman B. Ryder, “The Cohort as a Concept in the Study of Social Change,” American Sociological Review 30 (1965), pp. 843-861. 16)Karl Mannheim, “The Problem of Generations,” in Paul Kecskemeti (ed.), Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge (London: Routledge, [1928] 1952), p. 79. 17)Sigmund Neumann, “The Conflict of Generations in Contemporary Europe from Versailles to Munich,” in Vital Speeches of the Day 5 (New York: New York City Publishing Co., 1939). 18)John Crittenden, “Aging and Party Affiliation,” Public Opinion Quarterly 26 (Winter 1962), pp. 648-657. 19)J. Patrick Boyd and Richard J. Samuels, “Prosperity’s Children: Generational Change and Japan’s Future Leadership,” Asia Policy 6 (July 2008), pp. 15-51. 20)Jack Dennis (ed.), Socialization to Politics: A Reader (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1973). 21)Thomas Norman Trenton, “Generation X and Political Correctness: Ideological and Religious Transformation among Students,” Canadian Journal of Sociology 22-4 (1997), pp. 417-436. 22)Howard Schuman and Jacqueline Scott, “Generations and Collective Memories,” in N. Schwarz and S. Sudman (eds.), Autobiographical Memory and the Validity of Retrospective Reports (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1989), p. 359. 23)David O. Sears and Nicholas A. Valentino, “Politics Matters: Political Events as Catalysts for Pre-adult Socialization,” American Political Science Review 91 (1997), pp. 45-65. 24)Paul DiMaggio, “Culture and Cognition,” Annual Review of Sociology 23 (1997), pp. 263-287; S. Moscovici, “Notes toward a Description of Social Representations,” European Journal of Social Psychology 18 (1988), pp. 211-250. 25)Kent Jennings, “Residues of a Movement: The Aging of the American Protest Generation,” American Political Science Review 81-2 (1987), pp. 367-382.

Ⅳ. The Democratization Movement and the Birth of a New Political Generation

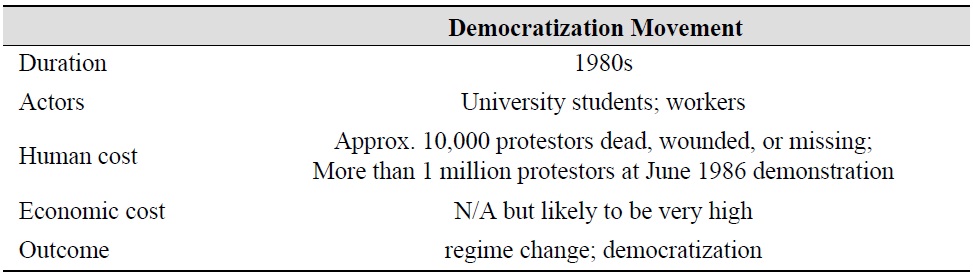

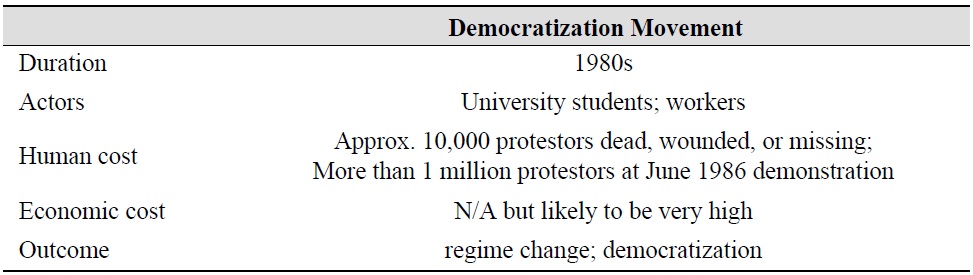

One of the most significant historical events in modern Korean history has been the democratization movement of the 1980s. It was a transformative historical experience in that it brought about the change of political regime from military-led authoritarianism to civilian-led democracy.26) As Table 1 shows, the event was high on scale, costs, and duration, and hence there is ample reason that the event may have led to the formation of a salient political generation.

[Table 1.] The Scale, Costs and Duration of the Democratization Movement

The Scale, Costs and Duration of the Democratization Movement

The democratization movement during the 1980s saw some of the bloodiest political protests in modern Korean history, and lasted for a decade, albeit sporadically. Several million people participated in the movement throughout the decade. Although no reliable data could be obtained, it is very likely that the event resulted in great economic costs.

The democratization movement was ideological in nature, and was closely tied with the movement for national unification. The main constituents of the democratization movement were antimilitary university students and workers. Perceiving the United States to be on the side of the military, they developed anti-American views.27) Believing that the hardline anticommunist policies of the military regime were hindering the development of inter-Korean relations, they became supportive of close engagement with North Korea. Hence the democratization experience produced a generation that preferred closer ties with the North and greater independence from the United States.

The core underlying ideology of the democratization generation was the notion of people (

The national liberation thesis was popular during the democratization movement, especially among the university student demonstrators.29) The thesis states that the “original sin” of the separation of Korea lies with the superpowers and their geopolitical conflict, and thus the solution to the unification problem can come not from the superpowers but only from the two Koreas themselves.30) Therefore, in order to achieve the unification problem, two conditions were crucial. First, outside powers need to stay out of Korean affairs, and second, inter-Korean relations have to be improved. On this basis, they could justify their anti-US, pro-North Korea foreign policy preferences.

The democratization movement produced a salient political generation that holds distinctive emotions, perceptions and policy preferences toward North Korea and the United States. The democratization generation holds a more benign view of North Korea, believing that the North’s brinkmanship diplomacy results from its dire economic conditions. Thus as long as those circumstances are averted through economic assistance, the North will be just like any other rational actor in international affairs. Moreover, the North’s problems stem to a large extent from the containment policy adopted by the conservatives in Korea and the United States. South Korea, they argue, must maintain a persistent engagement with North Korea to build up mutual trust and confidence.

Given the historical context from which the democratization generation emerged, I hypothesize that it would have the following generational effects with respect to the United States and North Korea.

I turn now to test the validity of the hypotheses using the EAI elite survey in the following section.

26)Se-gil Park, Rewriting Modern Korean History (Seoul: Donbaegae, 1989). 27)For more details, see the following US report “Background Explanation of Kwangju Incident,” available at

Ⅴ. Generational Effects on South Korea’s Foreign Policy

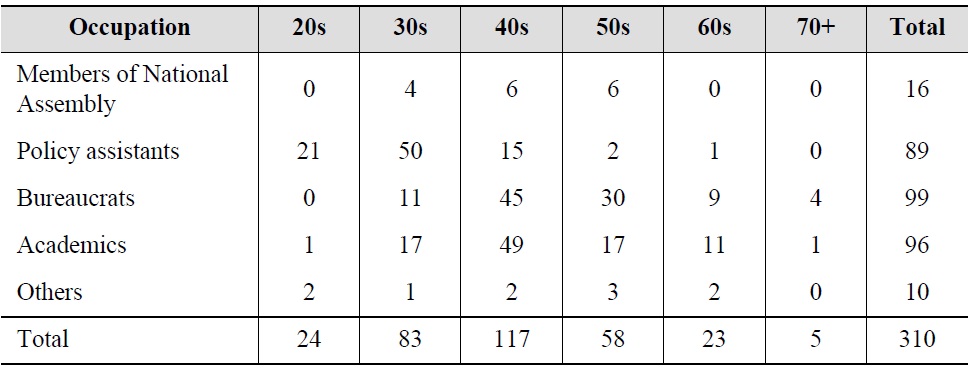

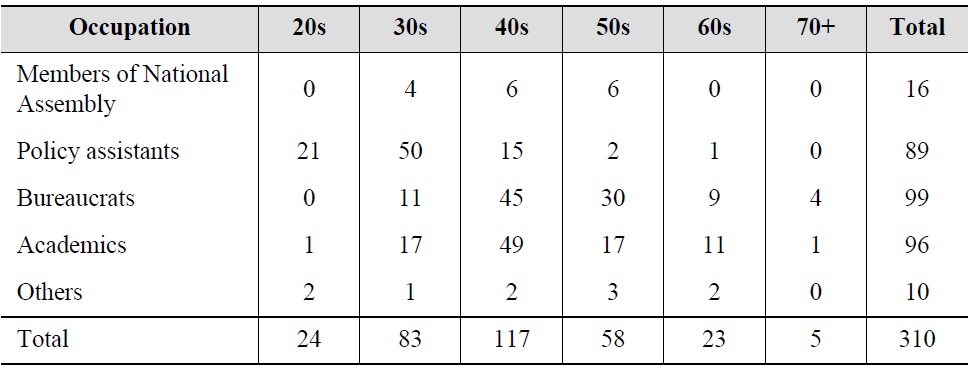

The EAI elite survey contains 310 responses from what could be broadly called the political elite of Korea, including members of the National Assembly and their policy assistants, government bureaucrats, and academicians. The breakdown of the survey composition by age and occupation is given in Table 2.

[Table 2.] The Composition of the 2005 EAI Elite Survey

The Composition of the 2005 EAI Elite Survey

There are four dependent variables in the model. The first two measure the like-dislike views of North Korea and the United States, and is measured on a scale from 0 to 100, with a higher number denoting more favorable feelings. We believe that sentiments toward a foreign country are an important factor influencing foreign policy decisions. The third dependent variable measures support or opposition for the continued stationing of the US troops in Korea after Korean unification. The respondent was asked, “Do you think that the US troops should continue to be stationed on the Korean peninsula after Korean unification?” The final dependent variable is the perception regarding North Korea’s possession of nuclear weapons. Although this question has been resolved in the affirmative today, it was still an open question in 2005 when the survey was conducted. The respondent was asked, “Do you believe that North Korea possesses nuclear weapons?”

The key independent variable of interest is the democratization generation defined by the duration of the democratization movement of the 1980s as well as by the scope of political socialization, i.e., 18-25 years old during the time of the transformative event. Hence there are three generations in the model: the democratization generation (those aged between 34 and 50 at the time of the survey), those younger than the democratization generation, and those older than the democratization generation. For the latter two age groups, we do not expect a generational effect, as they did not experience transformative historical event that coalesced them as a distinctive and salient generation.

A number of control variables are included. Obviously, the respondent’s party affiliation influences his sentiments, perception, and policy preferences toward the United States and North Korea. As is well known, the conservative party adopts a more hardline policy toward North Korea and favors the traditional alliances ties with the United States, while the progressive party takes a contrasting position. The Grand National Party and United Liberal Democrats are coded as the conservative party, while Uri Party, Millennium Democratic Party, and Democratic Labor Party are coded as the progressive party. 1 denotes conservative party, -1 progressive, and 0 for no identification with either party.

Age is a continuous variable from 18 to 83. We include the age variable because an alternative hypothesis to the generational hypothesis can be a linear effect of ageing on the dependent variables.31) The maturation model of generation suggests that sociopolitical views would change in a linear manner as citizens age. Hence the inclusion of age would provide a more stringent test for the generational hypotheses.

Gender is a binary variable. It is difficult to predict the effect of gender, but in this article it is hypothesized that males would have harsher views toward the North and favorable views toward the United States. This is mainly because of the compulsory military service Korean males go through. The training is in cooperation with the United States and geared toward meeting a potential attack from North Korea. 1 denotes male, and 0 denotes female.

I also include the media exposure variable. Given that the Korean media is generally conservative, we believe that the more one is exposed to the media, the more likely s/he has favorable views toward the United States and unfavorable views toward North Korea. Media exposure is measured as an equally weighed combination of the number of times the respondent reads newspapers every week and the number of times s/he watches TV news.

Finally, the regional organization variable asks whether or not one supports a Northeast Asian regional organization. We treat this question as an indicator for the importance of regional cooperation. If answered “yes,” then we expect that that person would hold more favorable views of the North, since it is obviously important to have good feelings about the potential members in order to form an organization.32)

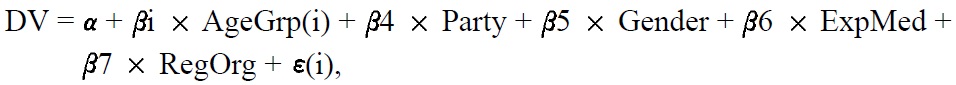

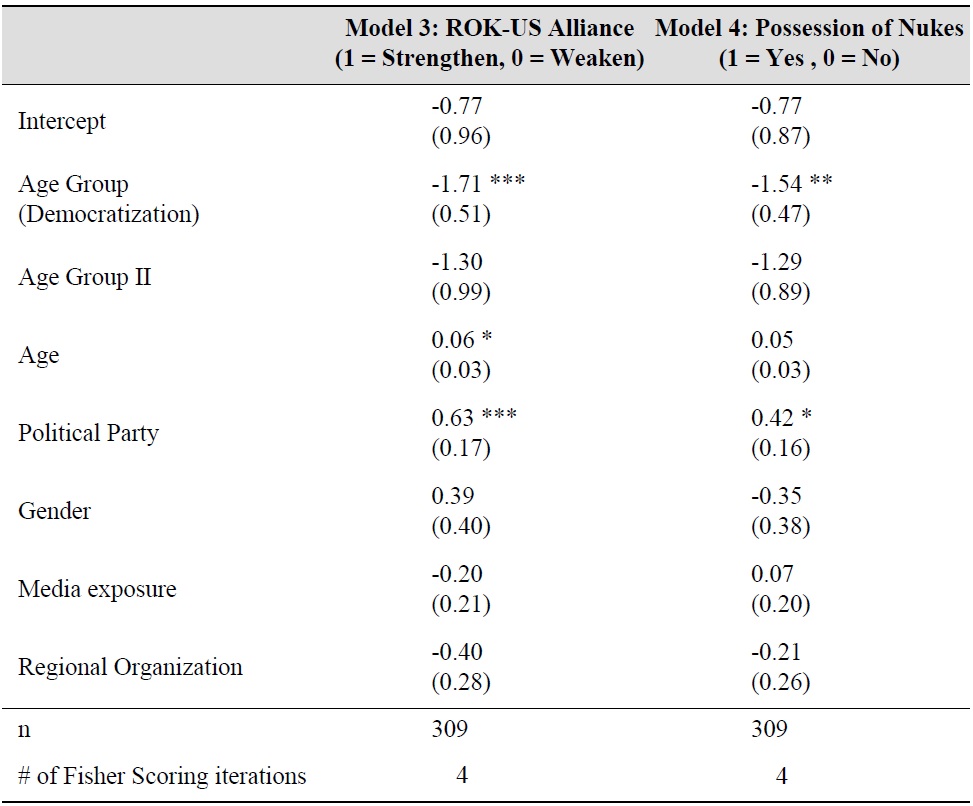

Thus the base model is as follows:

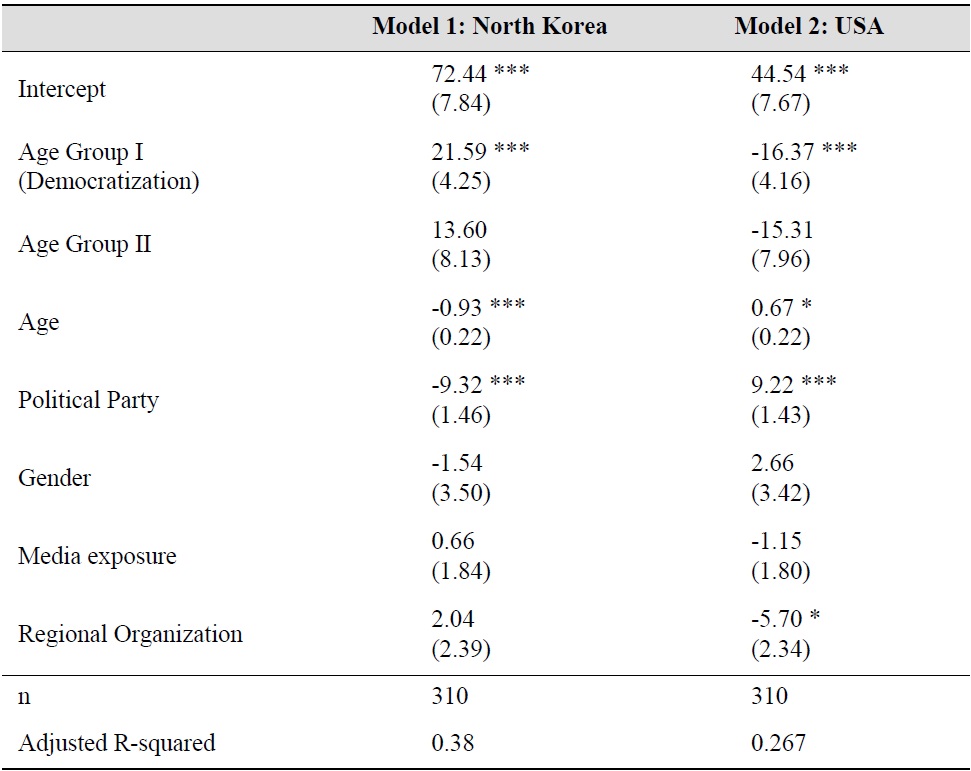

We first examine the generational effects on sentiments toward North Korea and the United States. Table 3 presents the results of the least-squares estimates of generational effects on sentiments. Model 1 shows the generational effect on sentiments toward North Korea, while Model 2 shows the effect on sentiments toward the United States.

[Table 3.] Generational Effect on Sentiments toward North Korea and USA

Generational Effect on Sentiments toward North Korea and USA

The results provide strong support for the sentiments hypothesis. As expected, the democratization generation holds more favorable sentiments toward North Korea and less favorable sentiments toward the United States. Equally important for my argument is the fact that the other two generations are not statistically significant, which suggests that people who have not experienced common transformative historical events are unlikely to form a distinctive political generation.

There are two other significant variables affecting sentiments toward North Korea and the United States. The statistical results suggest the presence of a linear effect of ageing on sentiments toward both North Korea and the United States. As Korean citizens age, they tend to have negative sentiments toward North Korea and positive sentiments toward the United States. On average, sentiments toward North Korea worsen by 0.93 points, while sentiments toward the United States improved by 0.67 points, as age increases by 1 year.

The last significant factor is political party identification. As hypothesized, identification with the conservative political party increases favorable feelings toward the United States and decreases sentiments toward North Korea, while the opposite effect exists if one supports the progressive party.

Lastly, the Regional Organization variable is statistically significant in Model 2. If one believes that the creation of a Northeast Asian regional grouping is necessary, then it has a negative effect on sentiments toward the United States. But the variable is not statistically significant in affecting sentiments toward North Korea.

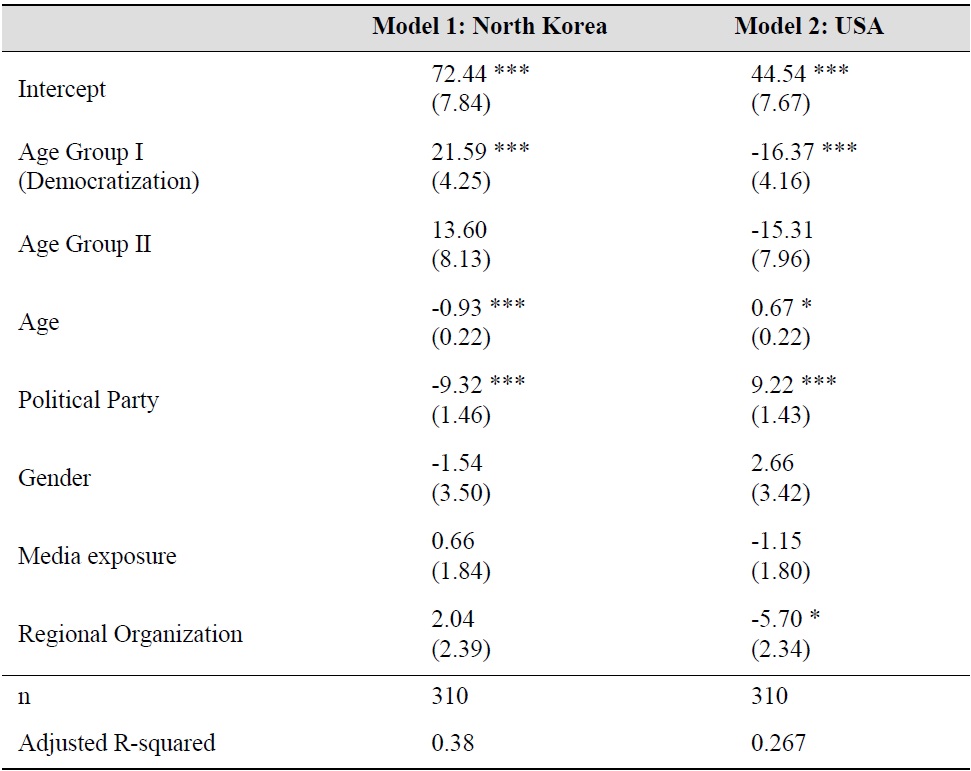

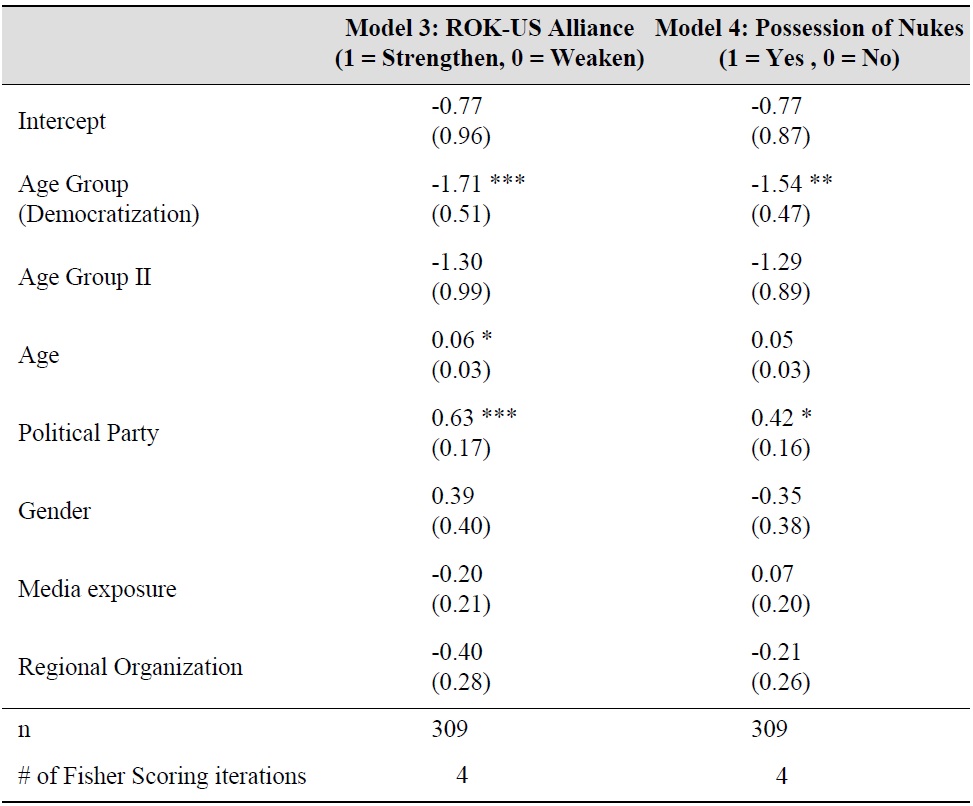

Table 4 presents the results of two logistic regression analyses, testing generational effects on one’s view of the ROK-US alliance and his/her belief concerning the possession of nuclear weapons by North Korea in 2005. Once again, the results are in accordance with the theoretical expectations and provide strong evidence for generational effects.

[Table 4.] Generational Effect on Foreign Policy Preferences and Perception

Generational Effect on Foreign Policy Preferences and Perception

On the issue of whether or not to strengthen the ROK-US alliance after Korean unification, the democratization generation believes that the alliance should be weakened, which is consistent with their desire for greater independence from the United States. Once again, it is important to note that the other two generations are not statistically significant.

Two other variables are significant: Age and Political Party. Age has a positive effect on support for the strengthening of the ROK-US alliance, although the magnitude of the coefficient is rather small. Political party affiliation is also important. If the respondent identified with the conservative party, then s/he is more likely to support the strengthening of the ROK-US alliance after Korean unification than those respondents who identified with the progressive party.

On the issue of North Korea’s possession of nuclear weapons, there was a negative effect of the democratization generation on the perception that North Korea possessed nuclear weapons in 2005 when the survey was conducted. This is consistent with the expectation that when there is a lack of clear information, the democratization generation would tend to interpret North Korea in a benign way.

Only one other variable is statistically significant, and that is the political party variable. Not surprisingly, identification with the conservative party increases the likelihood of perceiving that North Korea possessed nuclear weapons, while identification with the progressive party had a negative effect on the perception.

The regression analyses provide strong evidence that the democratization holds positive sentiments toward North Korea and negative sentiments toward the United States. It also has a more benign perception of North Korea, and prefers weakening of the ROK-US alliance after Korean unification. No other generation is statistically significant in the models—the democratization generation is the only significant generation. As argued, this is because the other two generations did not experience a transformative historical event comparable to the event of democratization.

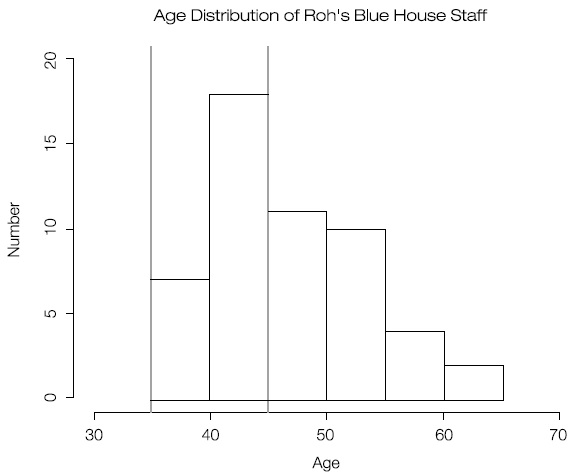

Finally, Figure 3 shows that the democratization generation was the dominant generational group represented in the Roh government (i.e., those aged between 34 and 50 at the time of the survey), consisting approximately of 70% of the Blue House staff.

31)I tested for a curvilinear relationship between age and DVs by including the squared age term. The squared age term is then not statistically significant. This is probably because age becomes a huge value once squared. Given the change of + and - signs, however, it is unlikely that the relationship between age and DVs is a simple linear relationship. 32)I exclude the education and income variables, as there is little variation. The inclusion of both variables has little bearing on the main findings.

Ⅵ. Alternative Explanations and Implications for Future Korea’s Foreign Policy

Several arguments could be put forward to explain the changes in South Korea’s foreign policy during the Roh administration. Those focusing on structural causes point to the end of the Cold War as the catalyst for improving inter-Korean relations.33) Some others who privilege materialist explanations point to the enhanced material capabilities of South Korea, which resulted in the desire for a greater voice and role in the alliance relationship and enabled the South to induce the North to the negotiating table through economic aid.34) Others emphasize the rise of anti-Americanism in Korea in the period as the critical factor for Korea’s new approach toward the United States.

Although these arguments all have some merit, they are insufficient to explain Korea’s foreign policy changes in this period. The end of the Cold War certainly created an enabling environment within which South Korea could redefine its relations with the erstwhile foes such as the Soviet Union, China, and North Korea, but it only provided the outer parameters within which a new form of Korea’s foreign relations could take place, and left its direction and contents completely undetermined. Indeed, the foreign policy changes under examination in this article took place almost more than a decade after the Cold War ended.

The same can be said about Korea’s enhanced material capabilities, as it cannot account for the timing and contents of Korea’s policy change. This argument implies that sentiments and policy preferences toward North Korea and the United States are a linear function of aging, given that a more-or-less linear increase in Korea’s material capabilities. But as the regression analyses show, age is not a significant variable when the generational effects are taken into account. Furthermore, according to one account, the South’s material capabilities had already exceeded those of the North by the early 1980s,35) and the dire economic situation in the North throughout the 1990s widened the gap between the two Koreas.36) But the actual changes only began to take place in the mid-2000s.

The rise of anti-Americanism is a more challenging alternative explanation.37) The argument here is that anti-Americanism was high in Korean society at the time Roh became president because of the accidental killings of two Korean girls by an American tank in operation,38) and thus the Roh administration simply had no choice but to reflect the popular sentiments in its foreign policy.

Besides the fact that this argument cannot explain the unprecedented extent of engagement of the Roh administration with North Korea, it suffers from two other problems, however. First, well before the tragic incident occurred, Roh had already begun promoting his jaju approach to the United States during his presidential campaign. Indicative of this is one of his campaign slogans, which was refusal to “kowtow to the Americans.”39)

Second, and more importantly, there were no international or domestic political situations that constrained and compelled the Roh administration to seek a revision of the ROK-US alliance and improve the inter-Korean relations. They did not have to reflect the popular anti-American sentiments by attempting to redefine the ROK-US relations. Here it is useful to separate issue-oriented/functional from deep-rooted/ideological anti-Americanism.40) What the Korean public demanded after the tragic incident was an instance of the issue-oriented/functional anti-Americanism, while the actual US policy the Roh administration undertook was motivated more by deeprooted/ideological anti-Americanism. Thus it is doubtful how much the sudden increase of anti-American sentiments at a particular time can explain Korea’s foreign policy changes designed to have a far-reaching effect on the ROK-US relations.

What does all this mean for Korea’s future foreign policy orientation? This article has analyzed the effect of the democratization generation on sentiments, perceptions, and policy preferences with regards to North Korea and the United States. But it is also likely that there can be one other salient and distinctive political generation in South Korea, that is, the generation borne out of the historical experience of the Korean War. It is often referred to in the media as the “war generation.” While the analysis of the war generation could not be analyzed in this study due to the limitation of the dataset, it is likely that the war generation would have a significant effect on sentiments toward North Korea and the United States as well as on perceptions and policy preferences.

The war generation went through a different historical experience of anticommunism, which led to the advent of conservative politics in South Korea. The historical event of the Korean War was high on scale, duration and costs, as it lasted for three years and resulted in economic costs of approximately 23 trillion dollars and human casualties of more than 600,000 soldiers and 1 million civilians.41) Hence, it would likely hold contrasting sentiments, perceptions, and policy preferences than the democratization generation. Indeed, during the Roh administration, both political generations often clashed over issues concerning North Korean nuclear weapons and ROK-US alliance.

The politics of generational differences are not an issue of the bygone past. As the recent incident of the

A few simple predictions can be drawn from my analysis and argument. The democratization generation has emerged as a political force in Korea, and it will continue to be a force to reckon with in future Korean politics. This is despite the fact that president Roh has passed away. His political followers still occupy important positions as provincial governors, party leaders, and so forth, and attract much public support. On the contrary, the war generation is dwindling, as most of them have passed away or fallen out of political power. Hence, on balance, there will likely be greater domestic voice that Korea’s future foreign policy be oriented away from the United States and closer to North Korea. This will clearly be the case if the democratization generation captures political power again in the future.

However, other than the democratization and war generations, there is no politically salient generation in Korea. The rest of Korean society does not take on any particular generational features of political significance, and their foreign policy preferences are not ideologically motivated. Thus if they become the dominant political voice in Korea, then Korea’s foreign policy will be just like any other country and will be driven by a combination of international and domestic factors with the aim of maximizing Korea’s national interests. Of course, the devil lies in the definition of national interests. For example, if the alliance with the United States were perceived to serve Korea’s national security, then these politically nonsalient generations would desire to maintain and enhance the relations. If not, they would seek to alter the terms of the alliance to their benefit. If engagement with North Korea were perceived to be necessary for the interests of South Korea, then they would pursue engagement. If not, however, they would be willing to put engagement on hold or even pursue a hardline policy toward the North.

In either case we are likely to witness changes in ROK-US and inter-Korean relations in the future. As Kim argues, the Korean perception of the US forces in Korea and of North Korea has changed much in the recent years,44) and this trend is likely to continue. There could be several reasons for this, but one critical reason that this article has suggested is the emergence of the democratization generation and weakening of the war generation. The days when the ties with the United States were assumed to be essential to Korea are simply gone, and those who seek to maintain the alliance will have to make efforts to convince the Korean public the utility of the alliance.

33)Byung Joon Ahn, “North Korea’s Foreign Relations After the Cold War,” in Manwoo Lee and Richard Mansbach (eds.), The Changing Order in Northeast Asia and the Korean Peninsula (Seoul: Institute for Far Eastern Studies, Kyungnam University, 1993). 34)The December 2002 government report on South Korea’s North Korea policy makes this point explicit by stating that the South’s reconciliatory and cooperative policy toward the North is based on the ever-increasing differences of material power between the two Koreas in favor of the South and the ensuing confidence the South has due to its economic and political developments. See Ministry of Unification, 2002, p. 2. 35)Joseph Chung, “North Korea’s Economic Development and Capabilities,” Asian Perspective 11-1 (Spring-Summer 1987), p. 55. 36)Kongdan Oh and Ralf Hassig, “North Korea between Collapse and Reform,” Asian Survey 39-2 (March-April 1999), pp. 297-298. 37)For a good discussion of anti-Americanism in Korea, see Gi-Wook Shin, “South Korean AntiAmericanism: A Comparative Perspective,” Asian Survey 36-8 (August 1996), pp. 791-794. 38)David Kang and Victor Cha, “Think Again: The Korea Crisis,” Foreign Policy 136 (MayJune 2003), pp. 20-28. 39)“Times Topics,” New York Times (23 May 2002), available at

The purpose of this article is to show that a political generation matters for foreign policy analysis. I have argued that the emotions and foreign policy preferences of the democratization generation—the core constituents of the Roh administration—is the key to understanding South Korea’s foreign policy changes during this period. This generation is produced by a transformative historical event, namely, the democratization movement of the 1980s. I have argued and shown that generational effects are not a simple function of enhanced material capabilities of Korea, but rather are the result of specific historical events that generated specific sentiments, perceptions, and preferences in those who experienced those events.

Three caveats should be made about my argument. First, the survey was conducted of an unrepresentative sample of Korea’s political elite. As such, one should be careful not to generalize it to Korea’s elite, let alone the entire Korean populace. The purpose of the article was a probe test examining the potential validity of political generation as a causal factor for Korea’s foreign policy change. Despite not being representative, the EAI survey has the advantage of capturing detailed views of some segment of Korea’s sociopolitical elite when most opinion surveys examine public views. Given that foreign policy decision making still falls largely within the domain of the elite, it is important to examine the elite’s sentiments, perceptions, and preferences.

Second, I am not claiming that generation is the only important factor in Korea’s foreign policy. Like all other states in the international system, Korea’s foreign policy is the result of a particular political coalition in domestic politics, bureaucratic bargaining, and international systemic constraints. My argument is simply that we cannot have a comprehensive understanding of Korea’s foreign policy changes during this period unless we pay attention to a salient political generation and their particular emotions and policy preferences. Knowing and understanding the democratization generation is the first and most important step in grasping why the Roh administration initiated policy changes vis-à-vis the United States and North Korea.

Lastly, one must not assume that all members of the democratization generation subscribe to the same sentiments, perceptions, and policy preferences. In fact, “defection” is common within a salient generation, as it is possible to be resocialized into a new set of attitudes, emotions, and values throughout life. There are prominent conservative politicians who belong to the democratization generation. Indeed, future research should explore this topic of who defects from dominant generational views, which would greatly enrich our understanding of how generational views and beliefs are maintained or discarded over time. But the existence of