Until recently mental time travel has mainly been characterized as mentally projecting forward or backward in time from the present moment (e.g., Addis, Pan, Vu, Laiser, & Schacter, 2009;Schacter & Addis, 2007a, b; Tulving, 1972, 2002). By synthesizing findings from cognitive psychology and cognitive linguistics and by additionally applying cognitive-linguistic methodology, Stocker (2012a) then introduced the idea—based on a sketch by Talmy (2000, pp. 86–87)—that in addition to this basic type of mental time travel (projecting backward or forward in time from the present moment), there might also be more complex types of mental time travel. For instance: a person may mentally project back from the present moment to a particular point in time in the past, but may additionally also conceptualize mentally projecting forward from this past point to a “later time” that is still in the past. Such examples can be referred to as examples of nested mental time travel (projecting forward in time embedded within projecting backward in time) (cf. Stocker, 2012a, p. 408). Investigating the conceptual structure underlying the linguistic use of

In the first part of this article (Sections 2–3), it is investigated how this anteriority/posteriority versus past/future distinction can help us to reveal the complex mental time travel that is underlying the pluperfect and future perfect. A major goal here is to substantially refine our understanding of possible cognitive phenomena that can occur in mental time travel along a sequence of two events; this part of the investigation will lead to a range of novel distinctions that involve two-event mental time travel and mental perspective. In the second part of this article (Sections 4–5), the two-event analysis of the first part is used as a starting point to approach the cognitive structure of mental time travel along more than two events. Again, a range of novel distinctions will be offered. In the discussion (Section 6) implications of the findings of the previous sections are related to cognitive modeling of time and memory (Section 6.1) and to possible basic differences in human versus animal temporal cognition (Section 6.2).

The theoretical strategy I adopt is the same as used in Stocker (2012a): using language as an entree to a conceptual level that seems deeper than language itself (Pinker, 2007; Talmy, 2000). This strategy is supported by recent findings that many conceptualizations observed in relation to our use of language also exist in mental representations that are more basic than language itself (e.g., Boroditsky, 2000; Casasanto & Boroditsky, 2008; McGlone & Harding, 1998; Núñez, Motz, & Teuscher, 2006). In the present investigation, language (cognitive-linguistic analysis) can assist us to identify complex forms of mental time travel—complex forms of mental projection through time.

The basic theoretical framework used is Talmyan concept structuring(Talmy, 2000), with the further refinement for temporal cognition by Stocker (2012a). There are many other basic theoretical frameworks that one could adopt when investigating the temporal cognition underlying the use of the tense system or when investigating the conceptual structure of mental time in general—for example: formal accounts of tense (e.g., Comrie, 1985; Declerck, 1986; Jespersen, 1924; Reichenbach, 1947), conceptual semantics (Jackendoff, 1987, pp. 398–402; cf. also Pinker 1989, pp. 205–206), formal semantics (e.g., Bennett & Partee, 1978; Montague, 1973; Pendlebury, 1992), or temporal (tense) logic (e.g., Allen, 1984; Kowalski & Sergot, 1986; Lichtenstein & Pnueli, 2000; Prior 1967). While the current investigation is basically set in a Talmyan framework, it also, as we will see, benefits greatly from the formal-tense analysis of Comrie (1985). One of the main motivations for choosing Talmyan concept structuring as a basic theoretical framework for the present investigation is that it offers a ready means to incorporate mental temporal perspective (Stocker, 2012a, b; Talmy, 2000, pp. 68–76+86–87). In the other above-mentioned approaches (formal tense, conceptual semantics, formal semantics, temporal logic), mental perspective is usually not considered or is only mentioned marginally, without incorporating it into the formal descriptive apparatus (e.g., in Jackendoff, 1987, p. 399). In contrast, in Talmyan concept structuring, perspective is an integral part of the overall theoretical descriptive system.

Before we begin with the analysis of mental time travel in multiple-event memory and foresight in the next section, let us attempt to characterize more precisely what cognitive-linguistic analysis suggests what “mental time travel” is. We might first note that language suggests at least two basic conceptual-metaphoric possibilities how mental projection through time might be carried out: whole-body motion and gaze direction. This is exemplified in (1):

The conceptualization of whole-body motion (1a) through time corresponds to what has been referred to as the moving-ego metaphor in the conceptualmetaphor literature (e.g.,

For the assumption that we mentally construe a time line when conceptualizing time, there is a lot of empirical evidence—it is just the

2. Perspectival mental time travel along two events in the past (pluperfect)

Since the pluperfect (

As we will see later on in this section, a still more refined characterization of the meaning of the pluperfect—rather than saying that it signifies “past in the past”—is to characterize it as “anteriority in the past.” To start investigating the temporal-conceptual structure underlying the pluperfect, we use one of Comrie’s own examples for illustration (1985, p. 66):

According to Comrie the temporal relations underlying the use of the pluperfect can be formalized in the following terms (1985, p. 125):

As has just been demonstrated, (3) can correctly predict all temporalrelational structure of the pluperfect. The question we now turn to is: How could mental temporal perspective (Stocker, 2012a; Talmy, 2000, pp. 72–76+86–87) be added to this basic account of the temporal-relational structure of the pluperfect? One theoretical solution to this question, the one to be adopted in this article, is to integrate Comrie’s findings into the theoretical framework of Talmyan concept structuring—because Talmyan concept structuring can describe temporal relations and temporal perspective in one coherent theoretical framework (Stocker, 2012a; Talmy, 2000). As a starting point, let us reformulate Comrie’s pluperfect formula in Talmyan terms. In Talmyan concept structuring, spatial or temporal relations are captured with the notions of Figure (

We again exemplify the formalized temporal relationship with (2). Now it is F1 which stands for the event which is to be located in time (John’s leaving). G1 stands for the temporal reference point (Mary’s emerging from the cupboard) in relation to which F1 is defined. Thus (4) correctly predicts that F1 (John’s leaving) occurs before G1 (Mary’s emerging from the cupboard). However, G1 also functions as another F, since the temporal position of G1 is also defined in relation to the present moment. Hence, one is in a position to postulate that G1 (Mary’s emerging from the cupboard) also functions as an F (a second F in the overall temporal complex: F2 ) whose temporal position is defined in relation to the present moment (which functions as a second G: G2 ). Thus, (4) also correctly predicts that F2 (Mary’s emerging from the cupboard) occurs before G2 (the present moment).

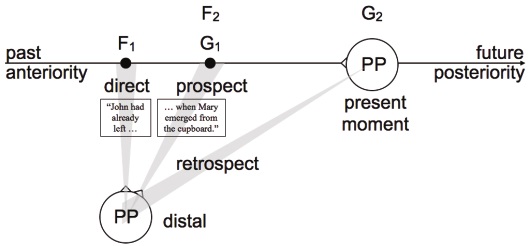

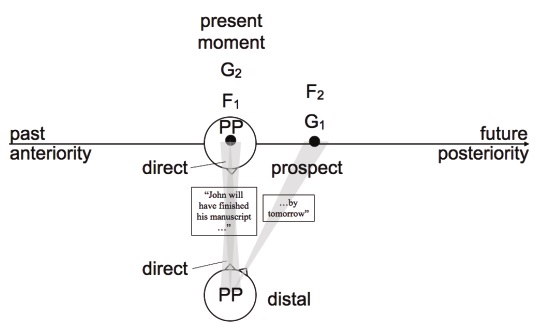

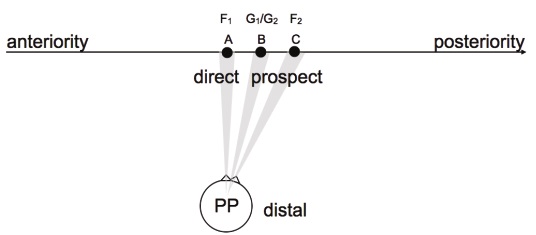

Thus far, Comrie’s pluperfect (3) and the Talmyan pluperfect (4) formalization are equipotent in terms of theoretical explanatory power: they both correctly predict the complex temporal relations that underlie our use of the pluperfect. But having it phrased in Talmyan terms allows us now to add mental temporal perspective (Stocker, 2012a; Talmy, 2000, pp. 72–76+86–87) to the temporal-relational description. Both Talmy and Stocker have cognitive-linguistically argued in detail that a complex temporal sentence (a temporal sentence with a main and a subordinate clause) underlies a temporal direct viewing of the F event in relation to the content of the main clause and a temporal indirect (prospective or retrospective) viewing of the G event in relation to the content in the subordinate clause. Taking over this analysis (see Stocker, 2012a; Talmy, 2000, pp. 72–76+86–87 for argumentation), we derive at the perspectiveincluding, temporal-conceptual structure underlying our use of the pluperfect as it is depicted in Fig. 1.

When taking a look at this figure, the temporal structure—and perspectival cognition thereof—might at first glance seem identical to the conceptual structure underlying our use of a temporal complex sentence containing

In other words, what Comrie is saying is that the pluperfect is basically speaking not “a past in the past” (i.e., this can only be deduced), but anteriority in the past (since he says that

Additionally cognitive-linguistic analysis of complex temporal sentences in relation to Talmyan mental perspective points (PPs) suggests that F and G are cognized as points (punctual events) on the mental time line and they are mentally cognized from a distal PP (as detailed in Stocker 2012a; cf. also Talmy 2000, pp. 61–62). A distal PP means mentally zooming out as much from an event as to collapse the entire duration of an event to a single temporal point. The self needs to zoom out this much in order to be able to cognize two events—that is the relationship between the two events—from one perspective point. Note also that the observation that the pluperfect indicates that self travels back from the present moment to a point in time prior to another past event (to F1 ) means that the reference point in the past (G1 ) can only be located in a prospective (later) direction when viewed from the perspective of F1 . Thus the self at the point in the past that is prior to another event in the past must mentally travel (look)

What does the Talmyan approach to analyze mental time travel underlying the pluperfect add to the more traditional approach of Comrie? In other words, what is the advantage of having a geometric/perspectival complex as represented in Fig. 1 over having a temporal-relational formula as in (3)? I see three main advantages. First, the use of Talmyan Figure (F) and Ground (G) brings out clearly the notion that the past event which is not in the pluperfect clause (and for instance is in a subordinate clause) has two formal functions: that this event serves as temporal reference point (G1 ) as well as a point that is related to a reference point (F2 ). This double function comes out less clearly in Comrie’s formula, since the event that is not in the pluperfect clause is only assigned one symbol (only

Thus far in this section, we have investigated the meaning of the pluperfect. Morpho-syntactically speaking, most modern European languages form the pluperfect by combining an auxiliary verb that is marked for the past (e.g, simple-past or imperfect) with a verb in pastparticiple form. Simple-past/past-participle combinations to express the pluperfect feature for example in English (

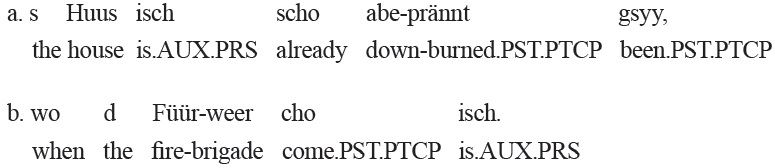

Since Swiss German (as other dialects in or near Southern Germany) lacks both the simple past and the pluperfect, it must resort to different means to express simple past as well as anteriority in the past. In such Alemannic dialects the compound perfect with the auxiliary verb in the present tense covers both the perfect (

A geometric and perspectival analysis of the doubled perfect leads to the same geometric and perspectival structure that has been proposed for the pluperfect (cf. Fig. 1). This is exemplified in Fig. 2.

Thus the analysis of the pluperfect and the doubled perfect allows one to propose that the same temporal-conceptual (geometric, perspectival) structure underlies these two different morpho-syntactic forms: perspectival mental time travel into posteriority that is embedded into perspectival mental time travel into anteriority in the past. That a language that lacks a pluperfect (like Swiss German) develops its own morpho-syntactic means to express “anteriority in the past” can be taken as evidence that the expression of this concept is important. Such a mental representation allows one to not only relate past events to the present moment, but also to relate past events in relation to other past events (cf. Comrie, 1985, p. 67).

Stocker (2012a) also argues in detail (by providing cognitive-linguistic evidence) that the schematic geometric representations, as for instance shown in Fig. 1–2, are not merely a didactic aid that allows us to illustrate the underlying cognitive-temporal structure. Rather it is proposed that such geometry is actually construed in our mind when we conceptualize time. For instance: the depicted time line is proposed to be an actual, mentally construed spatial structure in our mind that allows for mental time travel—for instance in relation to the pluperfect/doubled perfect by projecting one’s mental gaze along this mentally construed line once in a retrospective direction (to “anteriority in the past”) and once from there in a prospective direction (to the reference point in the past). As mentioned in the introduction already, the proposal that the “mental time line” is mentally construed when we engage in mental time travel is also supported by a growing number of recent experimental and other empirical findings. As also mentioned, the mental time line is for instance frequently conceptualized in relation to the cognizer’s body along the sagittal (back to front) axis or along the transversal (left to right) axis.

1Comrie’s (1985) ERS notation for the pluperfect represents a further development—and major departure—from the famous tense formulations of Reichenbach (1947, pp. 287–298; cf. also Jespersen, 1924, pp. 262–264). Comrie’s formulations are mainly taken over because it is Comrie’s analysis that allows one to characterize the pluperfect as involving “anteriority in the past” and the future perfect as involving “anteriority in the future”—which has major temporalcognition implications when one adds mental perspective to the pluperfect and future perfect constructions, as shall be demonstrated in this article. Taken over from Prior in the analysis in this paper, is the argumentation that there is no need to—as Reichenbach does—“make such a sharp distinction between the point or points of reference and the point of speech” (1967, p. 13). This is so, as also pointed out by Prior, because the present moment (“the point of speech”) itself can function as a reference point (as we will see, in our analysis the present moment will also be the point of memory recall). This argumentation of Prior is taken over by allowing the present moment to function as a Ground (see below in this article). “Ground” is the Talmyan technical term for what one might also refer to as a “reference point.” For a different theoretical approach to the notion of a temporal reference point see Declerck (1986, pp. 320–321). 2Note that this article follows Comrie in viewing the perfect (have eaten) and the pluperfect (had eaten) as—despite their formal similarities and despite the fact that many linguists treat them in a uniform way—as fundamentally different from one another from a temporal-conceptual viewpoint. Many arguments for a principal temporal-conceptual separation of the perfect and the pluperfect are given by Comrie (1985, pp. 77–82). To follow them up would go beyond the scope of the present investigation. The interested reader might also find Talmy’s temporal-conceptual analysis of the perfect relevant (2000, p. 95). 3There are two doubled-perfect variants, one with an auxiliary verb in the present tense and one with an auxiliary verb in the the simple-past tense (Blidschun, 2011, p. 134; Fabricius-Hansen, 2006, pp. 463–464; Litvinov & Radčenko, 1998; Rödel, 2007). However, in Swiss German (as well as in other dialects in or near Southern Germany) only the double perfect with the auxiliary verb in the present tense is in use (since the simple-past morpho-syntactic form is, as just mentioned, no longer in use). The present investigation only addresses the doubled perfect with an auxiliary verb in the present tense, since the main focus here is how language users who morpho-syntactically speaking have no simple past, nevertheless have a specific morpho-syntactic form that seems to have the same semantic function as the pluperfect does (to express anteriority in the past). 4Morpho-syntactically comparable forms to the doubled perfect (with comparable temporal semantics) seem to exist within the so-called temps surcomposés (“super-compound forms”) in French. However, native speaker judgments are not always in agreement on the meaning of these super compounds (Comrie, 1985, p. 76). For this reason, they are left out of the present discussion.

Since the future perfect (

Comrie concludes that the temporal-conceptual structure underlying the future perfect differs to the one underlying the pluperfect in only one way: the reference point (G1 in the Talmyan framework) is set in the future rather than in the past (Comrie 1985, pp. 69–74). Accordingly, Comrie (p. 126) formalizes the temporal-relational structure underlying the pluperfect in the following way (cf. with (3)):

Reformulation in Talmyan concept structuring (cf. with (4)); this will again enable us to integrate mental perspective (PP) into the temporal cognition:

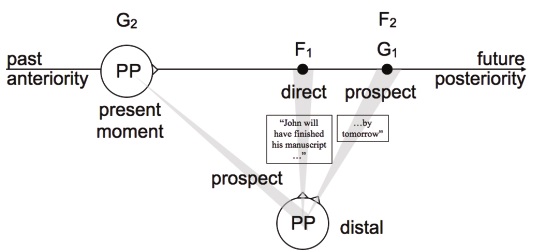

Both formulations, (6) and (7), encode a remarkable finding of Comrie about the future perfect, a finding that holds true cross-linguistically: that all that the future perfect indicates is that there must be a reference point (G1 ) in the future—but while the event referred to (F1 ) most typically also occurs in the future, it can also occur in the present or even in the past.Comrie:

This leads to three kinds of temporal relations that can underlie our use of the future perfect: future perfect with future interpretation, future perfect with present interpretation, and future perfect with past interpretation (Comrie, 1985, p. 70). Comrie has found these three possible temporalrelational interpretations of the future perfect in every language he has investigated that has a future perfect. However, he has found “no language” in which these three different interpretations are marked grammatically (e.g., marked morpho-syntactically) (p. 74). Hence, it seems that this degree of temporal-relational freedom of the future perfect is a nondispensable characteristic of the meaning of the future perfect. As further evidence that the event being referred to (F1 ; see below) in a future-perfect construction can be in the future, present, or past, Comrie also offers the following analysis:

As (8a) demonstrates, when the event being referred to (F1 ) is clearly restricted to taking place in the future only, then a past interpretation is no longer possible; the “yes” directly contradicts the question. However, this restriction does not apply to a future-perfect construction, as (8b) demonstrates; the “yes” does

It is in this context of the possible future/present/past interpretation of the pluperfect where the anteriority/posteriority versus past/future distinction becomes highly relevant: whereas the structure underlying the pluperfect (by deduction) can be characterized as “past in the past” (but is more precisely “anteriority in the past”; cf. previous section), this is no longer (in analog ways) true for the structure underlying the future perfect. As the analysis of Comrie demonstrates, the temporal relations underlying the future perfect could not (also not by deduction) be characterized as “past in the future” (since this would only correctly characterize the future perfect with past interpretation). The only characterization that can capture the sine qua non of the future perfect is “anteriority in the future”—that is, a reference point (G1) in the future in relation to which an earlier event (F1) is defined, an event that can be located in the future, present, or past.

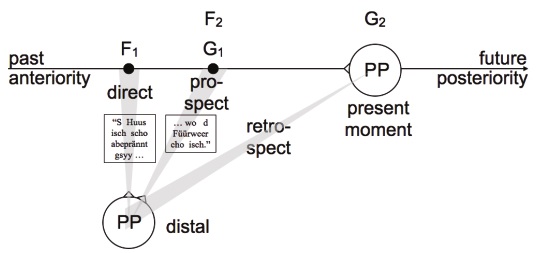

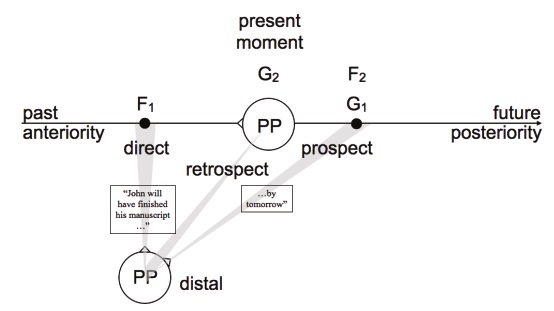

If we now add—as we did with the temporal-conceptual structure underlying the pluperfect—mental temporal perspective (Stocker, 2012a; Talmy, 2000, pp. 72–76+86–87), then these three possible interpretations of the future perfect naturally lead to three different kinds (subtypes) of nested dual mental time travel, as illustrated in Figs. 3–5.

The temporal-conceptual structure and perspective underlying the future perfect with future interpretation (Fig. 3) is largely identical to complex

The novel finding in the temporal-conceptual structure and perspective underlying the future perfect with present interpretation (Fig. 4) is that computational logic requires us to place the self twice at the present moment: the self must be located at the present moment in order to look out at the embedded self that is a distal distance removed from the time line (cf. Figs. 1–3); the second (embedded) self a distal distance away from the time line (but still co-located with the present moment) needs to look at the present moment on the time line so that F1 can be cognized in a temporally direct way (cf. also (Figs. 1–(3). More technically speaking, the novel proposal is the existence of a dual form of simultaneous temporal direct viewing, where both viewings are located at or co-located at the present moment. Note also that “mental time travel” into anteriority in the future is not really mental time “travel” in the present-interpretation case—since the anterior point happens to be at the present moment, the self at the present moment must cognize an embedded self a distal distance away from the timeline (but since this all happens at the present moment, the self does not really “travel” anywhere, at least not in a “forward/backward in time” sense).

The major novel observation in the temporal-conceptual structure and perspective underlying the future perfect with past interpretation (Fig. 5) is a looking forward from a past point (from the PP that is co-located with F1) to a future point (to G1)—that is, a prospective projection through mental time that starts off in the past and extends right into the future. This represents mental time travel into the future with the past as a departure point, passing by the present moment as it were. This is a novel finding since mental time travel into the future is normally always described as having the present moment as a point of mental departure (e.g., in Addis et al., 2009; Schacter & Addis, 2007a, b; Stocker, 2012a; Tulving 1985, 2002).

4. Perspectival mental time travel along a sequence of more than two events

The previous sections have demonstrated that the temporal perspective underlying the complex linguistic temporal forms of the pluperfect (as a window into two-event memory) and the future perfect (as a window into two-event foresight) can be described with the same basic perspectival dichotomy that has been used in describing the combinatory use of

The first event (event A) that is evoked by this sentence is established by the expression

Comparably, recalling a series of items in a typical recall task can also be viewed as remembering a sequence of more than two events—for instance, a five-item list (A-B-C-D-E) in a serial recall task (e.g., Brown et al., 2007). However, a multiple-event memory structure A-B-C-D underlying a sentence like (9) and a multiple-item memory structure A-BC-D-E underlying serial recall are, of course, quite different in terms of their timescale (in terms of long-term versus short-term memory). The multiple-event memory structure underlying (9) involves a conceptually larger timescale, a mental timescale that must allow marriage, divorce, and remarriage to occur (and thus involves long-term memory.) The multiple- item memory structure underlying five-item serial recall typically involves a much smaller mental timescale, typically one of seconds (e.g., Brown et al., 2007, p. 541) (and thus involves short-term memory). Despite these differences in timescale and memory system (long-term versus short-term), I would like to point out the theoretical possibility that these two examples of recalling a sequence of more than two events (or memory items) can be described with the same direct/indirect temporal perspective dichotomy that has been used in this article to describe the perspectival structure underlying the pluperfect or future perfect (Sections 2–3). This will be demonstrated below in this section. Given the proposed underlying similarities, I will refer to recalling a series of large-timescale events and to recalling a series of small-timescale memory items collectively as

It is certainly the case that the distinction between the mental construals of large-timescale events (long-term memory) and small-timescale memory items (short-term memory) is conceptually relevant for many psychological and neurophysiological aspects of memory (e.g., Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968; Baddeley, 1976; Glanzer, 1972; Izawa, 1999). However, this distinction does not seem relevant for the present mental-geometric (time line) and mentalperspectival investigation into memory. Both of these memory systems (or perhaps memory subsystems) can be described with the same mentalgeometric and mental-perspectival properties. The proposed long/short-term neutrality for certain aspects of multiple-event memory and foresight is also in line with the assumptions of the memory-retrieval model SIMPLE (

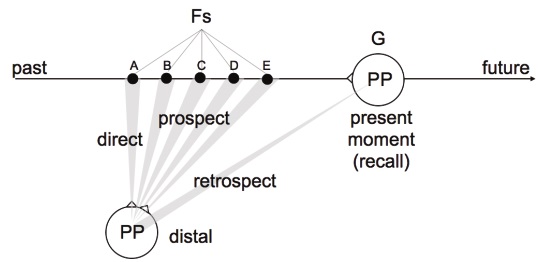

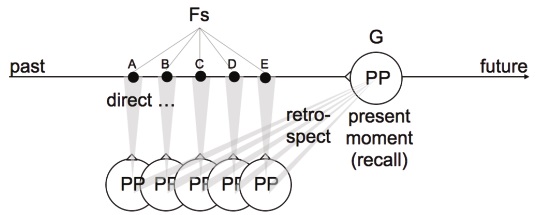

The two principal perspectival solutions that emerge for such A-B-C-D-… structures in relation to multiple-event memory and foresight are what I term the

At present, it is not clear if a cognizer typically uses the one-direct-andmultiple-prospective-viewings solution (Fig. 6), the all-direct-viewings solution (Fig. 7), or a combination of the two when recalling a sequence that involves two or more events (or yet another perspectival solution that has not been discussed here). We may note, however, that the all-direct-viewings solution would most likely involve greater economical cost. The self at the present moment (at recall) would have to constantly update its retrospective viewing: from recall to A, from recall to B, and so on to E. In contrast, in the one-direct-and-multiple-prospective-viewings solution, the retrospective viewing from the present moment could remain at A during the entire cognition of the complex memory, since everything unfolds prospectively from this one perspective point in the past. Future investigations could address the issue which direct/indirect-temporal perspectival viewings are used when recalling a sequence of multiple events.

In terms of Figure and Ground, the present moment in Figs. 6 and 7 can (as in all the previous figures) serve as a reference point (G) in relation to which the events A-B-C-D-E are located in the past (Fs).

We may further note that the all-direct-viewings solution is also logically possible for memory situations that only involve recalling two events (cf.Talmy, 2000, p. 74) and not only for memory situations that involve recalling more than two events (as has been investigated in this section). The all-direct-viewings solution for two-event memory structures seems possible, as long as the direct/indirect perspectival arrangement is not preset in some way—not preset for instance by devices like the pluperfect/doubled perfect or future perfect, which seem to evoke fixed arrangements of direct/ indirect temporal perspectives, as examined in Sections 2 and 3.

5On the distinction between episodic memory and episodic foresight see Suddendorf, 2013; Suddendorf & Redshaw, 2013; on the distinction between episodic and semantic memory see Section 6.1.

5. Episodic versus semantic perspectival mental time travel along a sequence of more than two events

This article has thus far investigated mental time travel in

Stocker has demonstrated semantic mental time travel only for two-event semantic memory; so the question remains if semantic mental time travel can also be found in multiple-event-memory and foresight that involve more than two events. This seems indeed possible, as can be demonstrated with language-as-an-entree analysis (for the proposal of identical or similar mental mechanisms underlying mental projection through time in episodic and semantic serial recall cf. also Kelley, Neath, & Surprenant, 2012; Neath, 2010; Neath & Brown, 2006; Neath & Saint-Aubin, 2011):

This sentence (an adapted version of a semantic-memory sentence from Stocker, 2012, p. 406) involves at least three underlying events. The first event (event A) that is evoked by this sentence is established by the temporal F (temporal Figure) of

Thus, the mental-geometric structure (line and regions thereupon) and the mental-perspectival structure of multiple-event memory and foresight can be argued to exist in both episodic and semantic memory. This provides evidence that multiple-event structure and perspectival cognition thereof are general properties of memory, general properties underlying both episodic and semantic memory (such general memory is sometimes also referred to as propositional or declarative memory). Despite the proposal that episodic and semantic memory share some basic mental-geometric and mentalperspectival properties, it is certainly the case that episodic and semantic memory are also different in many respects (cf. also above in this section). Episodic memory for instance involves a self at the present moment projecting into the past (or into the future in episodic foresight) (cf. Figs. 1–7) while semantic memory involves no self at the present moment as an inherent part of the temporal conceptualization (Fig. 8) (see Kim, 2013 for a systematic contrast of episodic and semantic memory and how this contrast can reflect in language).

The current investigation has proposed a range of novel notions for mental perspective in multiple-event memory and foresight, some of which have been shown to be relevant for mental time travel along two events and some of which are additionally also relevant for mental time travel along a series of events (along more than two events). The following novel distinctions have been identified in relation to perspectival mental time travel along two events: perspectival mental time travel into “anteriority in the past” versus perspectival mental time travel into “anteriority in the future” (Sections 2–3); perspectival mental time travel along a mental time line where past/future and anteriority/posteriority form two separate temporal reference frames versus perspectival mental time travel along a mental time line where past/ future and anteriority/posteriority conglomerate to a single nondispersible temporal reference frame (Sections 2–3); single temporal direct viewings versus dual simultaneous temporal direct viewings (Section 3); and looking into the future from the present moment versus looking into the future from the past (Section 3). The following further novel distinctions have been identified to relate to mental time travel along two or more events: the combination of one direct temporal viewing with serial prospective temporal viewings versus all serial temporal direct viewings (Section 4) as well as episodic versus semantic perspectival multiple-event memory and foresight (Section 5). These novel notions have only been possible to identify because the current investigation uses a basic theoretical approach—Talmyan concept structuring(Talmy, 2000) with the further refinement for temporal cognition by Stocker (2012a)—that inherently incorporates temporal mental perspective into the explanatory framework. Including perspective is an aspect that most approaches to temporal cognition have not incorporated in their basic descriptive framework (cf. Introduction).

In this discussion section, implications of the findings of the previous sections are now related to cognitive modeling of time and memory (Section 6.1) and to possible basic differences between human and animal temporal cognition (Section 6.2).

6.1 Mental geometry and mental perspective in memory models

One advantage that in general comes out of the current work (and of Stocker 2012a, 2012b) is that it offers a systematic and detailed explanatory framework how mental perspective can be included in a theory of temporal cognition and memory. The relevance of this can for instance be illustrated in relation to cognitive models of memory retrieval. Brown et al. (2007) have introduced a retrieval model they call SIMPLE (scale-independent memory, perception, and learning):

As in SIMPLE, the current investigation has also identified a self who is looking back from the present moment (point of recall) along a mental time line to multiple temporal points (locations) in the past (Sections 4–5). Unlike the current investigation, SIMPLE additionally also considers proximal and distal aspects of these temporal points on the time line. What the current investigation has identified in addition to SIMPLE is an embedded remembered self who is looking at the time line from a given point in the past (see also Sections 4–5). Future modeling approaches could address the question, whether it might be fruitful for temporalperspective-including models (like SIMPLE) to incorporate this “additional self” in the past. This then would allow such models to investigate if this embedded self (i) cognizes the memory items in the past in a temporally direct or temporally indirect (prospective or retrospective) way and (ii) if the embedded self cognizes the items in an embodied (field) or disembodied (observer) perspective (Crawley & French, 2005; Henri & Henri, 1896; Lorenz & Neisser, 1985; Nigro & Neisser, 1983; Piolino et al., 2007; Rice & Rubin, 2009, 2011; Stocker, 2012b). Such perspectival refinements are likely to be relevant for a recall model. For instance: In embodied-perspective memories one is known to retrieve richer accounts of affective reactions, physical sensations, and psychological states whereas in disembodiedperspective memories one is known to retrieve richer accounts of the external environment, such as where things were located in the remembered surroundings (e.g, McIsaac & Eich, 2002, 2004).

6.2 Mental geometry and mental perspective in human versus animal memory and foresight

The current investigation has provided evidence that mental geometry (time line and temporal regions on it) and mental perspective are relevant dimensions of mental time travel. More generally, this raises the question if these two cognitive properties—mental geometry and mental perspective— are basic and indispensable properties of human mental projection through time (cf. also Stocker, 2014).

Indeed, the question if mental time travel fundamentally involves mental geometry (spatializing time) and mental perspective, might also be helpful in the long-standing debate if animals mentally travel through time the way humans do or not. This debate has recently been resumed anew in a dialogue between Corballis (2013a, b) and Suddendorf (2013). Adding to this dialogue, Casasanto & Stocker (2013) point to work which suggests that the critical factor that distinguishes mental projection through time between the human and animal species might be the human capacity to spatialize time (Casasanto & Boroditsky, 2008; Stocker, 2012a), a capacity that has not yet been shown to exist in the animal species (Merritt, Casasanto, & Brannon, 2010).

Corballis (2013a, b) takes hippocampal place-cells in rats as evidence for animal mental time travel. Such neurons indicate that rats recall paths which they walked through in the past and even that rats imagine possible paths which they could walk through in the future (Foster & Wilson, 2006). Casasanto & Stocker (2013) point to a crucial difference between the spatial path for mental time travel in humans (Casasanto & Boroditsky, 2008; Stocker, 2012a) and the spatial path that the rat mentally projects through (Foster & Wilson, 2006): The rat can anticipate what

Findings of theoretical cognitive linguistics, experimental cognitive psychology, and mathematical cognitive modeling point to the possibility that mental geometry and mental perspective are indispensable dimensions of human temporal cognition and human memory and foresight.