The expression no matter, combining with an interrogative clause X, expresses ‘it doesn’t matter what the value is of X’ and displays many syntactic and semantic peculiarities. To better understand the grammatical properties of the construction in question, we investigate English corpora available online and suggest that some of the irreducible properties the construction displays can be best captured by the inheritance mechanism which plays a central role in the HPSG and Construction Grammar. We show that the construction in question has its own constructional properties, but also inherits properties from related major head constructions.

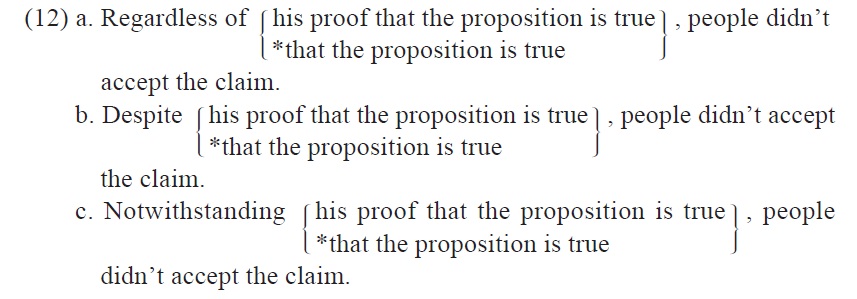

English employs many different types of the so-called ‘free-range’ constructions as illustrated in the following (Culicover 1999):

Syntactically, those in (1) are different from those in (2) in that in the former the subordinate clause is a complement of the expression no matter or prepositions like

In this paper, among these free range expressions, we focus on the properties of the

1Huddleston and Pullum (2002: 761) name such constructions ‘exhaustive conditional’, while Rawlins (2008) classifies these into three main types, ‘alternative unconditional’ ((2b)), ‘constituent unconditional’ ((2a)), and ‘headed unconditional’ ((1)).

II. Distributional Possibilities and Internal Structure

1. Distributional Possibilities

As noted in Quirk et al. (1985) and others, the NMC can take the full range of an interrogative clause as seen from the following attested examples:2

The possibility of having

The NMC basically functions as a modifier to the main clause, restricting its possible range. The modifying property can be observed from its distributional possibilities in sentence initial, medial, or final position:

These distributional possibilities indicate that the NMC is a subordinate clause modifying the main clause though its internal structure can be different from other subordinate clauses.

In terms of selectional and distributional possibilities, other free rangers can also select an interrogative clause and modify a main clause:

However, differences come from the fact that unlike these free rangers,

As seen in (7a), the canonical NP

Since the clause introduced by

An intriguing fact we observe from the corpus search is that

We take such cases as a different construction since the meaning of the

The other free rangers with similar meanings do not license a finite CP or S as their sentential complement even though they freely occur with an NP:

The

What this implies is that the

Based on these observations, we assume that there are two different types of the NMC, one combining with an interrogative clause with an unconditional meaning and the other expressing a concessive meaning with a declarative S or CP. In this paper, we focus on the former otherwise noted.4

2. Relatedness with the Verb and Noun Counterpart

The behavior of

Let us consider the main properties of the verb

The verb

There are cases where the verb

The extraposed property can be checked with the fact that we cannot replace the subject

The expression

But when the noun

Once again note that such a case cannot combine with an interrogative clause and functions as a free ranger:

The copula omission also tells us that

As noted here, in both cases no copula ellipsis is licensed.

As we have seen here so far, the expression

2The corpora we use in this research include 410 million words COHA (Corpus of Historical American English), COCA (Corpus of Contemporary American English), 100 million words BNC (British National Corpus), and 100 million words TIME Magazine Corpus of American English. All of these are freely available online. 3‘Concealed question’ NPs are those that can be interpreted as questions when they are complements of question-embedding verbs as in the following: (i) a. Kim has forgotten the price of the book. (=Kim has forgotten what the price of the book is.) b. Kim knows the time of meeting. (=Kim knows what the time of the meeting is.) For detailed discussion, see Grimshaw (1979). 4As hinted by Nakajima (1998), we could, of course, collapse these two into one type of construction, but following Rawlins (2008), we at this point differentiate these two.

III. Ellipsis in the No Matter Construction

In the NMC, we observe that the verb form of BE is frequently omitted when the conditions on the subject are satisfied. However, there are certain constraints on the subject to license its omission. For example, as given in (22), the subject must be a definite NP: it cannot be a pronoun or proper N, an indefinite generic, a quantified NP, or a demonstrative NP (cf. Haspelmath 1997, Culicover 1999):

Our corpus search also supports this claim:

We take this definite and generic condition on the ellipsis in the NMC is due to its interaction with the ‘copula’ ellipsis in English. For example, as noted in the literature, English comparative correlative construction also licenses the copula ellipsis with similar constraints on the subject:

However, note that what can be elided is not just the auxiliary verb

If we allow only the copula

Since

As long as the sluiced expression is a sentential constituent, we have legitimate cases:

As in canonical sluicing, we do not have sluicing with

IV. An Analysis: Interactions between the Lexicon and Constructions

1. Internal and External Syntax

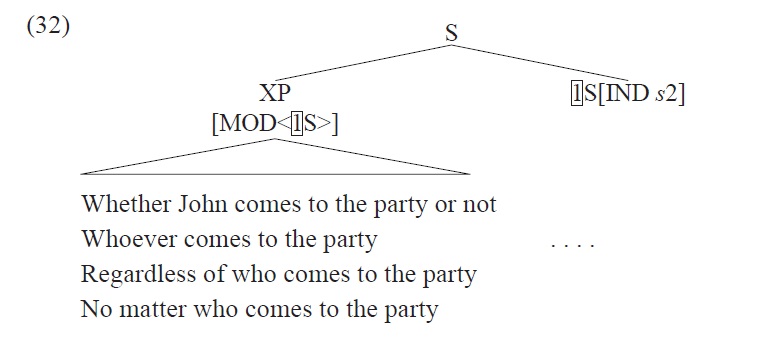

Before we provide an analysis for the NMC, consider the other types of free ranger or unconditional constructions:

As noted earlier, semantically, as noted by Rawlins (2008), all these are similar in that they are unconditional in the sense that the consequent ‘main’ clause is entailed irrespective of the antecedent ‘free range’ clause. For example, there is an ‘unconditional’ semantic relation between the two situations

This in turn means that the exhaustive conjunction of conditionals will be determined by the alternatives to the

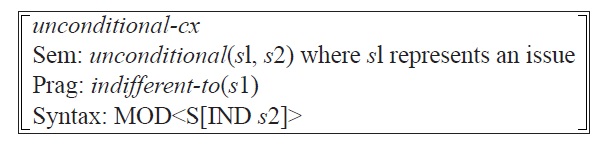

These syntactic and semantic properties lead us to assume the following constructional constraints general to the so-called unconditional constructions:

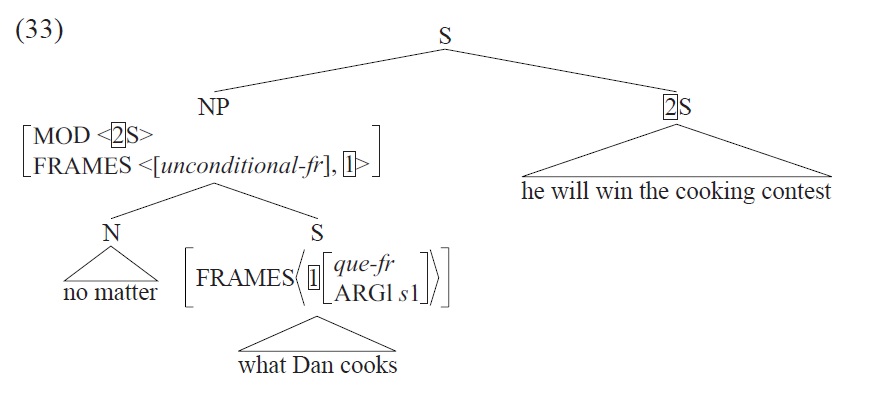

The constraints specify that the unconditional construction

As clearly represented by the structure, we can observe that the unconditional antecedent takes scope over the main clause, placing restrictions on the domains of operators in the scope.

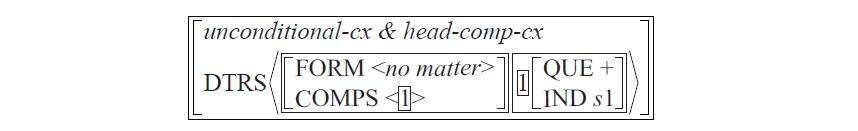

The NMC is a subtype of this general unconditional construction, inheriting these properties (cf. Kim 2008). However, it has its own idiosyncrasies, including the status of

Since this construction is a subtype of the

The structure correctly describes the fact that the NMC functions as a modifier to the main clause.

Note that we do not place any restriction on the structure of its complement. The only requirement is that it denotes a

2. More on the Interactions with Other Constructions

As we have seen earlier, the NMC also involves sluicing. This is natural since the complement of

Since the constraint requires the wh-expression to function as a filler, we would not generate examples like the following, which we repeat here:

Even though the

The sluiced antecedent is

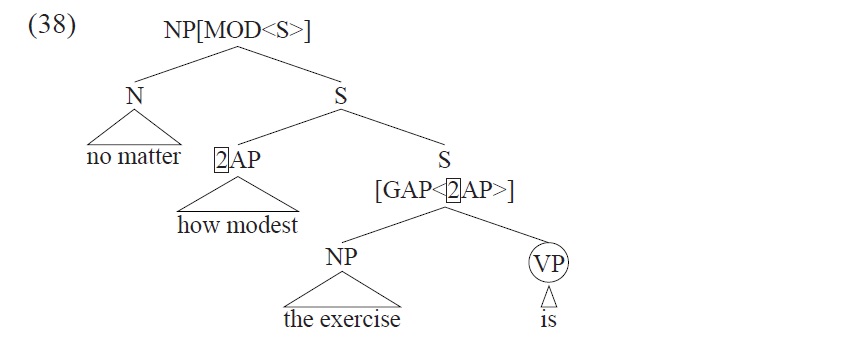

A further complexity arises from the copula ellipsis in the construction:

The ellipsis of the lower S is sluicing, but that of the circled VP is not. As noted in the previous section, we cannot simply say this is an ellipsis of the copula verb

Even though we refer to the VP level, the VP consists of only the copula verb

However, the informally-stated constraint will generate examples like the following:

In addition, the condition on the external argument will block examples where the subject is indefinite or a simple pronoun:

Given that the elided copula here has no semantic content, the copula-VP ellipsis including the sluicing data here is possible as long as its antecedent is discourse-salient. We leave out the exact formulations of these sluicing and copula-VP ellipsis in the present system, but we can at least observe that the NMC closely interacts with many other constructions including a variety of ellipsis.

5This differentiates if-conditionals from unconditionals in that the antecedent of the if-conditional denotes a proposition while that of the unconditional expresses an issue because of its semantic contribution of the interrogative clause. See Rawlins (2008) for further discussion. 6For a detailed description of frame-based semantics, see Michaelis (2011).

We have shown that the expression

Based on these observations and corpus search, we have sketched a construction-based analysis of the