COMMON POOL RESOURCE PROBLEM OR POLICY INERTIA?

Budget deficits arise from governments’ excessive expenditure. Early economists that examined the causes of budget deficits offer the tax-smoothing hypothesis which views the government as the “benevolent social planner” that always tries to balance the budget and predicts that deficits only arise under exceptional circumstances such as wars or recessions (Barro 1979; Lucas and Stokey 1983). However, recent studies have shown that budget deficits do happen in the absence of wars or recession and there are cross-national differences in budget deficits. Thus, many scholars have turned their attention to the effects of political factors on budget deficits. In this section, we briefly review two strands of the literature—

The

The

The two theoretical approaches differ in their causal mechanism but they share the same idea that predicts a centralization of political power to reduce budget deficits. Hence, some scholars have attempted to provide a more integrated approach of the two theories. For instance, Hankla (2013) criticizes that most studies only examine the patterns of budget deficits in parliamentary systems and argues that the dynamics of budgetary politics in presidential systems should be differentiated from that of parliamentary systems. Hankla (2013) finds that in presidential systems, unified governments do indeed produce low deficits but even divided governments tend to produce low deficits when fragmentation is high in the legislature. This is because the president’s political survival is not threatened by a fragmented legislature and thus, the president can co-opt small opposition parties when the legislature is fragmented whereas this would not be possible if a single opposition party controls the legislative majority (Hankla 2013). Hankla’s study emphasizes the importance of a central actor, or the president, that would solve the CPR problem but also highlights the impact of different executive-legislative relations in presidential and parliamentary systems on budget outcomes. However, Hankla’s (2013) theory only focuses on the impact of executive strength and legislative fragmentation on budget deficits in presidential systems.

1For discussions on the economic consequences of budget deficits see for example Gale and Orszag (2003). For political consequences of budget deficits, see Brender and Drazen (2008). 2Roubini and Sachs (1989a/1989b) argue that multiparty governments tend to have higher deficits because coalition partners want to deliver benefits to their constituents at the expense of the total tax burden. 3Although Roubini and Sachs (1989a/1989b) do not mention the term “veto players” in their articles, a part of their argument is similar to that of the veto players theory because they emphasize that multiparty governments tend to be slower in adjusting to fiscal shocks because the budget process is highly inefficient when there are many stakeholders in the government.

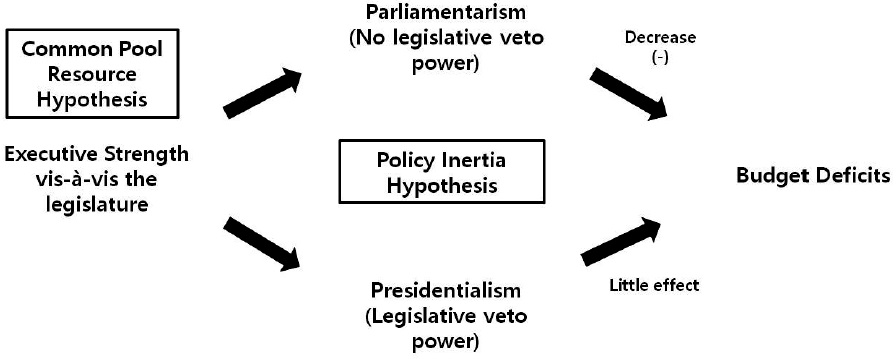

In this section, we will derive testable hypotheses from the two contending theories of budget deficits—

As stated in the CPR literature on budget deficit, an increase in the executive strength vis-à-vis the legislature decreases budget deficits because the executive, who represents the national constituency and considers the total tax burden, tend to prefer a balanced budget whereas the legislators tend to exploit the budget in order to deliver particularistic benefits to their constituencies. Thus, we expect that:

On the other hand, the policy inertia theorists argue that budget deficits arise in systems with multiple veto players. In order to change policies, certain veto players must agree to the proposed change and the presence of multiple veto players may stagnate the budgetary policymaking process, which, in turn, would undermine the government’s ability to reduce budget deficits (Tsebelis 2002; Tsebelis and Chang 2004). As for budgetary policymaking, how veto power is distributed among the executive and the legislature can have significant effects on budget outcomes because they can be

Next, we offer a

Under parliamentarism, the executive and the legislature are mutually dependent on each other for survival. As a result, legislators under parliamentarism tend to be disciplined by the parties and especially those legislators affiliated with the ruling parties tend to be more disciplined. That is because the prime minister, who is also the leader of the ruling parties, imposes strong discipline on his party members in order to reduce the risk of a defeat in legislative votes, which, in turn, would lead to a dissolution of the cabinet (Linz 1994; Mainwaring and Shugart 1997; Samuels and Shugart 2010). Moreover, the executive’s power to dissolve the legislature is another effective tool to suppress the narrow incentives of individual legislators.Under parliamentarism, the prime minister usually has the power to dissolve the parliament and to call for new elections. This would facilitate executive discipline on the legislature because the legislators should be less likely to challenge the prime minister at the risk of losing their seats in the new elections. It may be possible that the parliament’s vote of no confidence may discipline the executive but the prime minister, who is the leader of the ruling party, would be able to punish his party members for any attempts to dismiss the cabinet.4 Therefore under parliamentarism, the legislature does not have an institutional veto power, and an increase in the executive strength vis-a-vis the legislature (e.g., an increase in seat share of ruling party in the legislature) would thus decrease budget deficits.

Under parliametnarism, however, the legislature is an institutional veto player because it is independent of the executive to survive (Haggard and McCubbins 2001; Samuels and Shugart 2010). Legislators are thus less disciplined in presidentialism than their counterparts in parliamentarism. Hence the former tend to be more empowered to pursue individual goals. It may be argued that in the unified presidential government where president’s party controls the majority seats in the legislature, the legislature may not be considered as a veto player because of the partisan cohesion of the two branches. Nevertheless, the legislators still tend to be less disciplined than those in parliamentarism because the former have weaker incentives to comply with the president’s interests at the expense of their own interests due to the independence from the executive for survival (Linz 1994; Mainwaring and Shugart 1997). Thus, it can be expected that under parliamentarism, legislators tend to exploit national resources at the expense of a balanced budget in order to deliver benefits to their constituents, irrespective of executive strength over the legislature. Hence we expect that:

4Empirically, few prime ministers are defeated by a vote of confidence in parliamentary systems regardless of unified or coalition governments. For example, the parliament’s vote of no confidence defeated one prime minister in the United Kingdom since 1924, none in Australia, one in Germany since 1982, one in Greece, etc.

We test the above hypotheses using cross-national data of 49 countries. The dataset includes Argentina (2002-2004), Armenia (2003-2011), Australia (1999-2011), Austria (1995-2011), Bangladesh (2001-2006, 2009-2011), Belgium (1995-2011), Bolivia (2002-2007), Brazil (1997-2011), Bulgaria (1995-2011), Canada (1995-2011), Chile (2000-2011), Colombia (2001-2011), Denmark (1995-2011), Dominican Republic (2004-2010), Finland (1995-2011), France (1995-2011), Germany (1995-2011), Greece (1995-2011), Guatemala (1995-2011), Honduras (2003-2011), Hungary (1995-2011), Indonesia (1995- 1999, 2002-2011), Italy (1995-2011), Japan (2005-2011), South Korea (1995- 2011), Malaysia (1996-2011), Mexico (1995-2000), the Netherlands (1995- 2011), New Zealand (2001-2011), Nicaragua (1995-2011), Norway (2000-2011), Paraguay (1995-2011), Peru (1995-2011), the Philippines (2000, 2003-2011), Poland (2001-2011), Portugal (1995-2011), Russia (2006-2011), Singapore (1995-2011), Spain (1995-2011), Sri Lanka (1995-2011), Sweden (1995-2011), Switzerland (1995-2011), Thailand (2003-2011), Turkey (2006-2011), United Kingdom (1995-2011), United States (1995-2011), Ukraine (2006-2011), Uruguay (1995-2011), and Venezuela (1995-2005).

The dependent variable is

Because we use time-series-cross-sectional data and a continuous dependent variable, we construct a fixed-effects regression model to measure the interaction effect of executive strength and executive-legislative relations on budget deficits while controlling for unobservable time-invariant factors in regional contexts (e.g., similar historical experience, culture, etc.). The basic model for country

where R represents the region-specific dummy variables and

>

PARLIAMENTARIANISM/PRESIDENTIALISM

Using the World Bank’s Database of Political Institutions (DPI 2012), we generate a dummy variable,

Whether a country adopts parliamentarism or presidentialism is expected to interact with the executive strength in affecting the country’s budget deficit. Because the expectation is that as the executive strength over the legislature increases, budget deficits will decrease in parliamentary systems, we expect

In addition to those key variables of interest, several other factors may affect a country’s budget deficit. First, fragmentation in the legislature and in the cabinet should be controlled for. Fragmented legislatures, in which a large number of parties take parliamentary seats, and fragmented cabinets, in which a large number of parties take cabinet posts, tend to decrease the stability of the cabinets (Laver and Schofield 1990; Warwick 1994), and may thus undermine the executive’s ability to reduce budget deficit (Tsebelis 2002; Hankla 2013; Roubini and Sachs 1989a, 1989b; Hallerberg and von Hagen 1999).

Second, a country’s economic condition could affect the country’s budget deficit (Barro 1979; Lucas and Stokey 1983). The proponents of the tax-smoothing hypothesis argue that macroeconomic conditions may have an effect on budget deficits. We include

Third, political leaders in democracies may be more likely to increase budget deficits than their counterparts in autocracies, because the former tend to have a larger winning coalition (should receive support from a larger number of people) and would thus need to distribute benefits to a broader population (Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003). We thus use a dummy,

Finally, because we use time-series cross-national data, we control for time- and region-fixed effects. Dummy variables for observation years are included in the models in order to control for unknown time-invariant year-specific factors that may affect

5A country is democratic if (1) its effective executive is directly elected or selected by an elected assembly, (2) a legislature with multiple parties is elected, and (3) opposition parties or challengers to incumbents are allowed and have realistic chances of taking power (Cheibub et al. 2010). 6For example, there are only three observations (2002-2004) for Argentina.

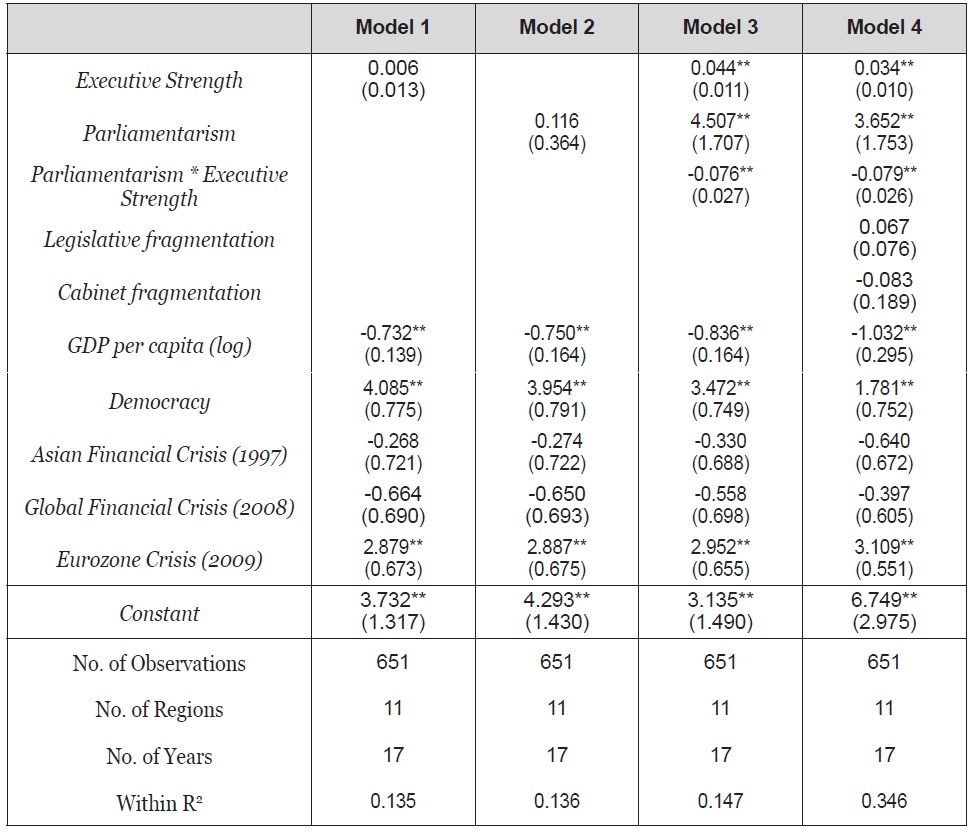

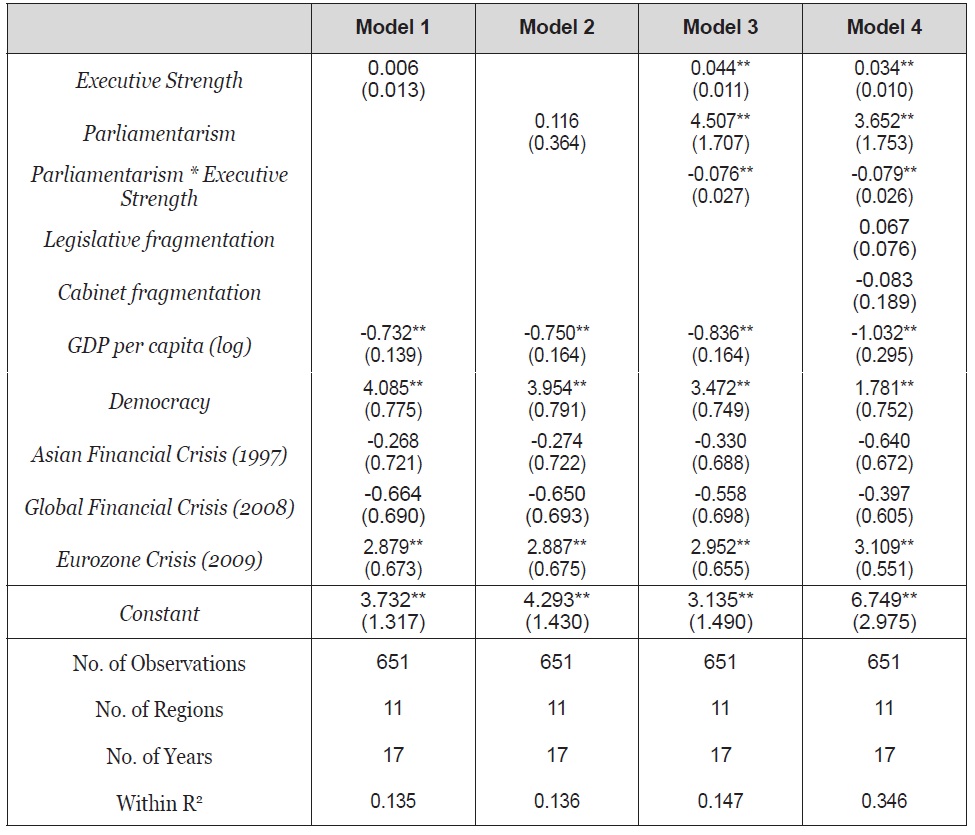

Table 1 shows the results of our analysis.

[Table 1.] Conditional Common Pool Resource Theory and Budget Deficits

Conditional Common Pool Resource Theory and Budget Deficits

In Column 1 of Table 1, we present the results with

Column 3 of Table 1 incorporates both

Some hypothetical examples can help to explain the relevant coefficients by comparing different executive-legislative relations—for example, presidential systems where presidents have strong control over the legislature compared to those where presidents do not control the legislative majority, and parliamentary systems where prime ministers’ parties control a majority of parliamentary seats compared to those where ruling parties are in a minority in the parliament. For example, the level of budget deficit in the presidential system where the president’s party takes 75% of legislative seats is 1.7% higher than that in the presidential system where the ruling party takes 25% of the seats (2.55% versus 0.85%). In contrast, the level of deficit in the parliamentary system where the prime minister’s party takes 75% of parliamentary seats is 2.25% lower than that in the parliamentary system where the ruling party takes 25% of the seats (0.28% versus 2.53%).

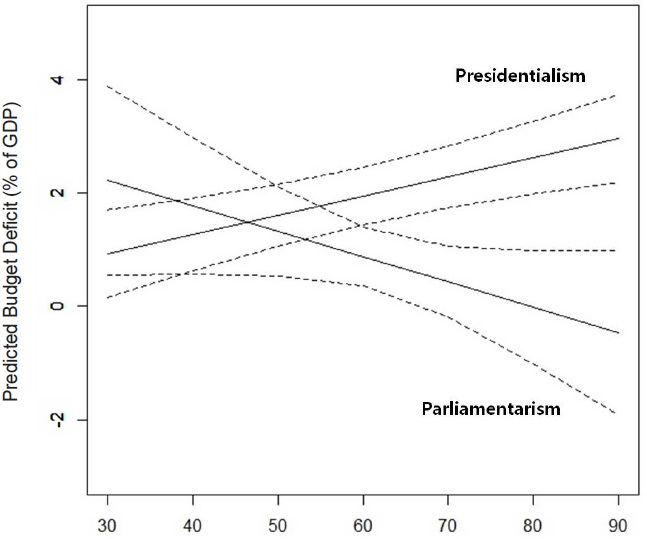

Figure 2 visualizes how an interaction between parliamentarism/ presidentialism and executive’s legislative seats influences the level of budget deficits.

As the executive controls more seats in the legislature, budget deficits decrease substantially in parliamentary systems while they do not alter significantly in presidential systems. Hence, the gap between presidentialism and parliamentarism widens as the legislative seats controlled by the executive increase. Comparing a few cases in the dataset can help interpret the results. In a presidential system where the ruling parties control over 75% of the parliamentary seats, such as the Philippines in 2006, budget deficits amount to 1.25%. Conversely, deficits amount to -1.91% or a surplus of 1.91% in a parliamentary system where the ruling parties control over 75% of the parliamentary seats, such as Thailand in 2006. The significant difference in the level of budget deficits (1.25% versus -1.91%) indicate that executive strength vis-à-vis the legislature has a significant impact in reducing budget deficits in parliamentary systems whereas such impact is not so significant in presidential systems. We can also compare these results with a set of cases in which the ruling parties control fewer seats. For example, budget deficits in the Philippines actually decreases by 0.05% (from 1.25% to 1.20%) in 2008 compared to 2006 despite the dramatic decrease in the ruling parties’ seat share (from 76.5% to 54.18%). Conversely, budget deficits in Thailand increases by 1.41% (from -1.91% to -0.5%) despite the slight decrease in the ruling parties’ seat share (from 75.4% to 65.83%). The substantive figures demonstrate that the impact of executive strength on budget deficits is significant under parliamentarism while it is not so significant under presidentialism. Thus, our analysis demonstrates that the variations of budget deficits across countries can be explained better with

Although the results of our analysis shown above conform to our predictions of the

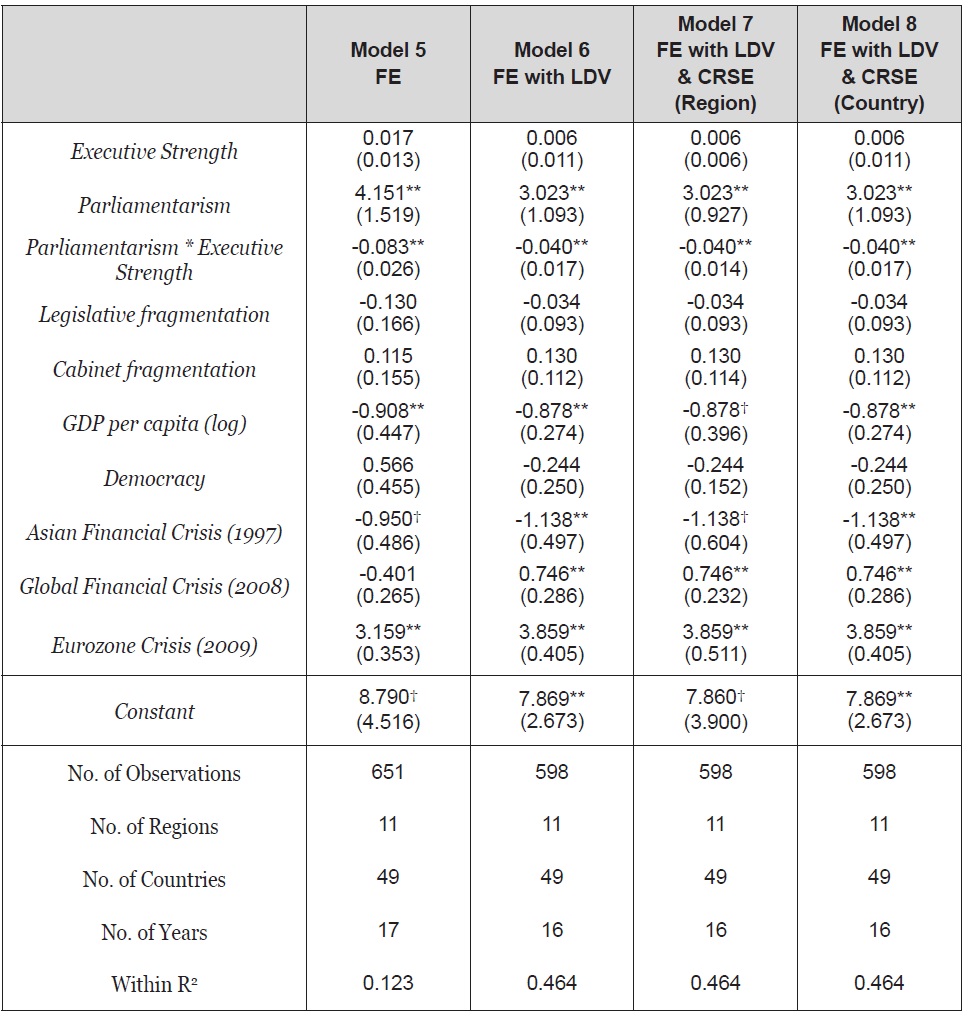

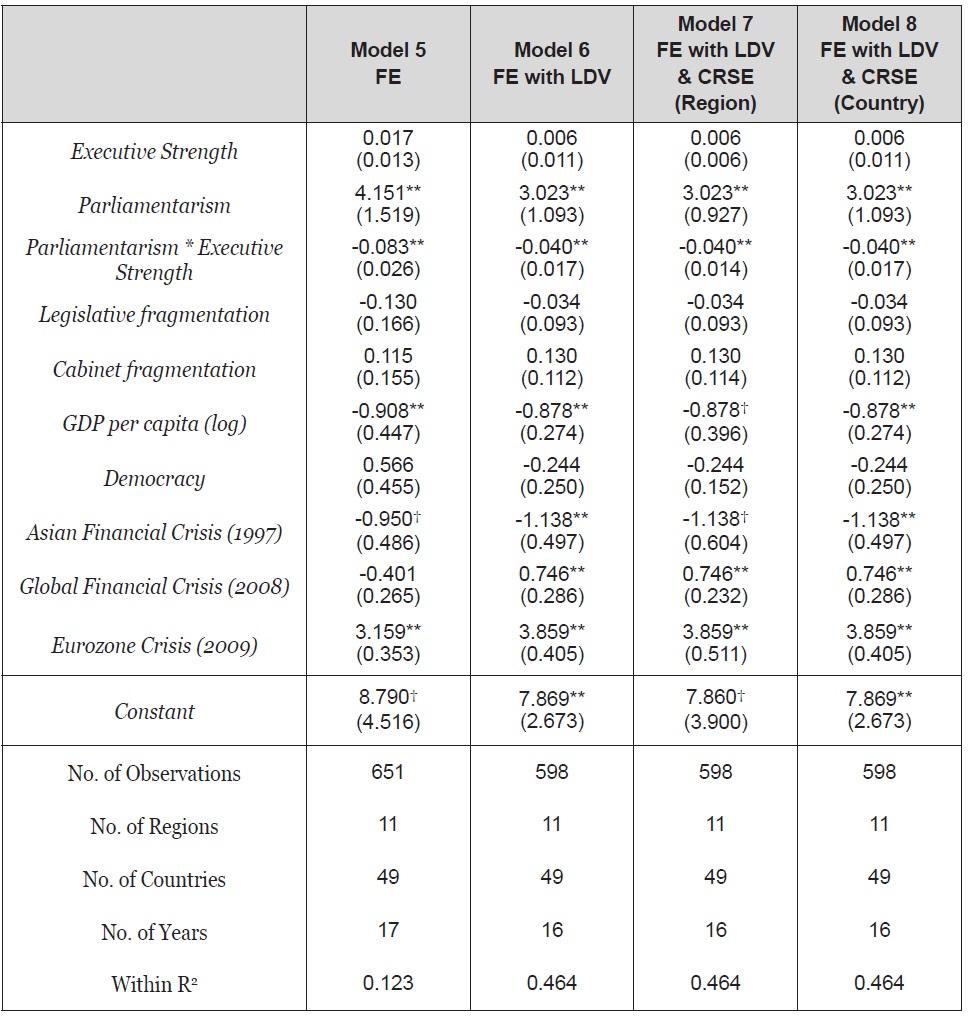

Thus, we check for the robustness of our results from the potential problems mentioned above by the following treatments. First, we rerun our model using the country-fixed effects model. The country-specific fixed effects controls for any country-specific time invariant factors that may have affect budget deficits.9 Second, we include a one-year lagged value of the dependent variable and rerun the model to control for autoregressive disturbances. Lastly, we rerun the models with cluster-robust standard errors (CRSE) at the region level. The cluster-robust standard errors controls for any additional region-specific time invariant factors, such as culture and similar historical experience, which may affect budget deficits. Moreover, the cluster-robust standard errors are not only robust to cluster-heteroskedasticity but also to within-cluster correlation (Cameron and Miller forthcoming). However, since the cluster-robust standard errors is more accurate when the number of clusters is large, we also run the model with clusterrobust standard errors at the country level. The results of our robustness analysis are shown in Table 2.

[Table 2.] Conditional Common Pool Resource Theory and Budget Deficits (Robustness Analysis)

Conditional Common Pool Resource Theory and Budget Deficits (Robustness Analysis)

As shown in Columns 1-4 in Table 2, the results of the robustness rtests are not substantively different from our analysis shown in Table 1. Column 1 shows the results of the country-fixed effects and the coefficient of the interaction term,

7This is also the reason why we do not separately control for electoral systems in our models. 8Since Parliamentarism is coded 1 for parliamentary systems and 0 for presidential systems, it can be predicted that the interaction effect of Executive Strength and Presidentialism is positively correlated with budget deficits. 9Although the random-effects model may be an alternative to fixed-effects model because one of our explanatory variables, Parliamentarism, is time-invariant and may perfectly correlate with country-specific effects. However, we choose to use the fixed-effects model for the following reasons. First, the random-effects model relies on an unrealistic assumption that unobserved country-specific effects are not correlated with the independent variables and thus, the random-effect model is both statistically and theoretically unreliable. Second, the variable of our main interest is the interaction term Executive Strength * Parliamentarism, which is time-variant, and thus the concern for perfect collinearity of the explanatory variable with the country-specific effects can be disregarded.

In this article, we investigate why countries experience different levels of budget deficits. We argue that the executive control over the legislature decreases budget deficits on the condition that the legislature does not have institutional veto power. Using the cross-national data on budget deficits in 49 countries from 1995 to 2011, we find that an increase in seat share of ruling party in the legislature decreases budget deficits in parliamentary systems; it has little impact in presidential systems.

We make at least two contributions to the literature on budget deficit with this article. First, we attempt to integrate the logics of the two contending theories— CPR versus PI—on budget deficits in which the CPR theory predicts that a strong executive will decrease deficits and the PI theory predicts that the decrease in the number of veto players will decrease deficits. In this article, we offer a

Secondly, this article demonstrates an interaction effect of executive strength and parliamentarism/presidentialism on budget deficits. While most of the pre- existing literature that study the impacts of political factors on budget deficits focused on either the effects of unified versus divided government or the number of parties in the cabinet/legislature (Roubini and Sachs 1989a, 1989b; Alt and Lowry 1994; Hallerberg and von Hagen 1999; Tsebelis 2002), this article focuses on the effects of the different dynamics of executive-legislative relations in parliamentarism/presidentialism on budget outcomes. Considering that most countries in the world have adopted either one of the two constitutional structures—parliamentarism or presidentialism—the findings of this article may have some practical implications for budgetary politics. For instance, parliamentary systems that suffer from high deficits, such as Greece, may be able to reduce deficits by increasing the seat share of the ruling parties in the parliament through elections or through forming grand coalitions whereas such efforts may not be so effective in reducing budget deficits in presidential systems.