This article claims that, with the emergence of the G2 era, mounting tensions between Korea and China have hampered the practical progress of these two countries’ “strategic cooperation partnership.” This article examines the popular perception of the current strategic threats and diplomatic challenges in the two countries, analyzing the results of Korean and Chinese public opinion polls. Observations on how such public perceptions affect the recognition of Korea-China relations are also presented. The study concludes with discussion on along what directions Korean and Chinese perception should change to promote the two countries’ strategic relationship in the G2 era.

Since diplomatic relations were established between Korea and China in 1992, the relationship between the two countries has developed rapidly, according to various numerical statistics. In terms of economic exchanges, the countries’ trade volume—which totaled no more than 6.4 billion USD in 1992—increased to 221 billion USD in 2011, multiplying 34.6 times over and exceeding Korea’s aggregate trade volume with the United States and Japan.1) Last year, the volume of direct investment flowing from Korea to China amounted to 50 billion USD, with the number of Korean firms in China reaching 50,000. China has become Korea’s top economic partner, and according to the 2011 figures, Korea is now China’s third-largest economic partner after Japan and the United States, although the figures exclude Hong Kong.2) The number of people travelling between the two countries has also increased in pace: from 130,000 people in 1992 to 6,410,000 people in 2011, recording a remarkable forty-nine-fold growth. A total of 130,000 people currently participate in student exchange programs (64,000 Chinese students in Korea and 68,000 Korean students in China) and direct flights run between the two countries 837 times a week.3)

The nature of Korea–China relations has also evolved since the “the good neighbor” days of “friendly cooperative relations” at the time when diplomatic relations were first established in 1992. In 1998, the countries announced they would pursue “cooperative partner relations in the twentyfirst century,” and in 2003, a new framework of “comprehensive cooperative partner relations” was inaugurated. More recently, as a result of the Korea–China summits in 2008, the countries’ diplomatic relationship has been enhanced even further, to the level of “strategic cooperation relations,” the highest grade of diplomatic ties recognized by China since 1978.4)

However, although Korea–China relations have developed and strengthened without any major hindrances for years—and the two countries have enjoyed a sort of diplomatic honeymoon—conflicts rose to the surface around the dawn of the twenty-first century. The Garlic Dispute in 1999–2000 put an end to the special honeymoon period for the two countries and relations were normalized based on mutual interests.5) Thereafter, many diverse conflicts and disputes rose to the surface: the 2003–2004 dispute over the history of Goguryeo Kingdom; the dispute over the Registration of Danoje Ceremony in Gangreung as an intangible cultural heritage site of UNESCO; the negative statement of the speaker of the Chinese Foreign Affairs Department on the Korea–US Alliance in 2008; the conflicts between South Korea’s strong stance against North Korea and China’s comprehensive policy for North Korea; the conflict related to the sinking of the

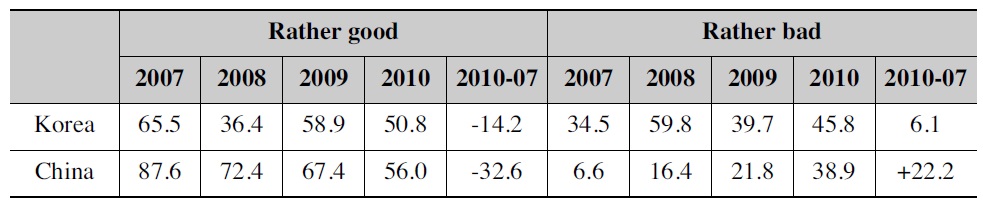

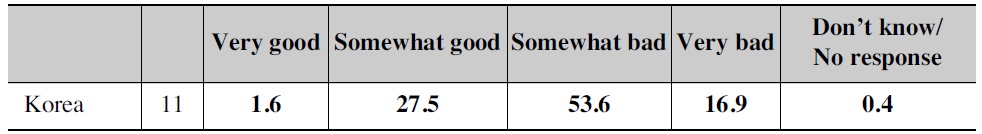

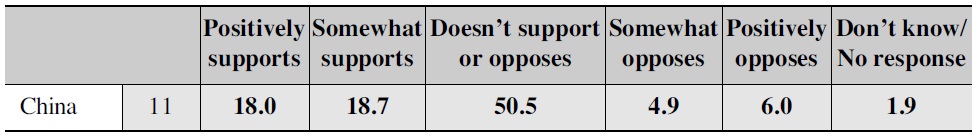

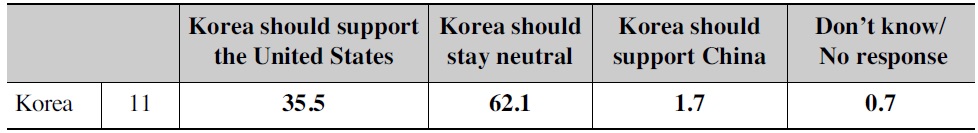

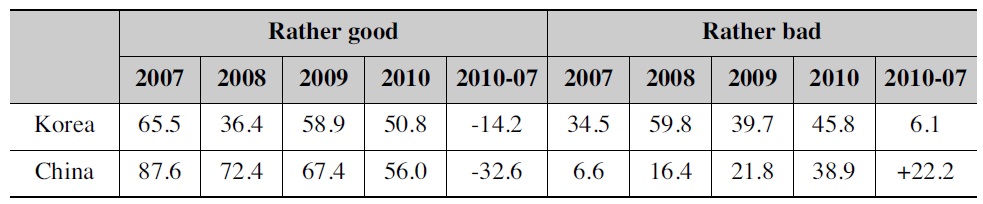

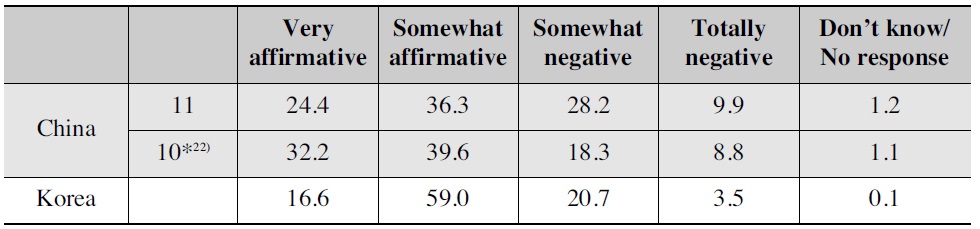

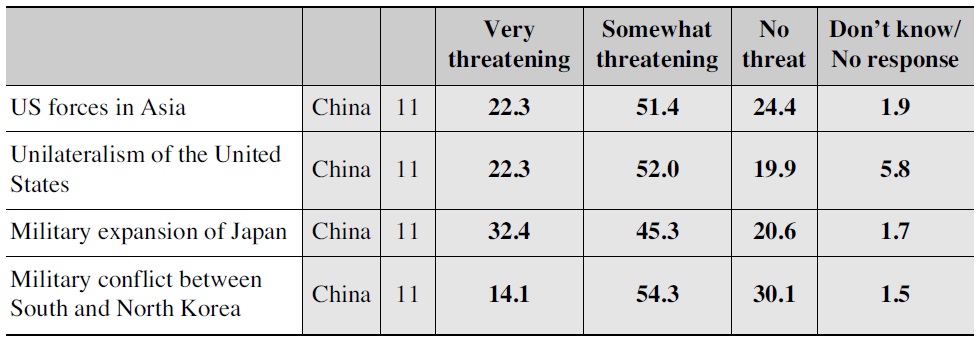

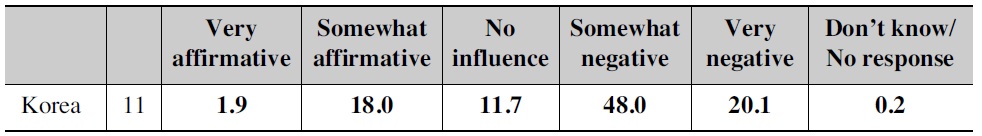

These conflicts have soured the public perception of state relations in both Korea and China and have stood as obstacles to the further development of a healthy strategic partnership between the countries. The results of public opinion polls readily corroborate this claim. As seen in Table 1, people in both countries appear to be recognizing that the relationship between the two countries is not improving, but rather deteriorating (see Table 1).

[Table 1.] Korean and Chinese Public Evaluation of Korea?China Relations

Korean and Chinese Public Evaluation of Korea?China Relations

It is worth noting that early on, the conflicts between Korea and China were mostly economic and cultural in nature, but from 2008, strategic concerns such as the Korea–US alliance, relations with North Korea, and the North Korean nuclear weapons program began to appear as major sources of diplomatic disagreement. In light of these pressing issues, the two countries upgraded their diplomatic relationship to the level of a strategic cooperation partnership to solve strategic issues with mutual cooperation. Ironically, conflicts over strategic issues have become the core subjects of dispute between the both countries.

In fact, Korea and China have not managed to create a substantial cooperative relationship in the political and diplomatic sense, in spite of their conspicuously successful economic partnership. Although more than forty summit meetings have been held and military exchanges have been made, summits consisting of reciprocal visits have been made no more than seven times and military exchanges have been made only superficially. The reason why cooperation between the two countries has been weak (in terms of the diplomatic and security sectors) is mainly owing to the presence of a perceptual gap between China’s recognition that Korea still stresses the importance of its relationship with the United States concerning its security issues, and Korea’s recognition that China is overly sensitive about the public debate pertaining to the North Korea problem. This gap is too large for a diplomatic quick fix and has impeded the development of better relations between the two countries.6)

With the rapid economic rise of China, the concept of the G2 (“The Group of 2”—the United States and China) has gained international currency, however informally. G2 is the term used to refer to the group of the strongest two countries in the world, the United States and China, which tackles together political and economic issues in the international community.7) What may be called the emerging “G2 era,” marked by the renewed and heightened interest of the United States in East Asia, solidly defines the China–US relationship as a key variable and determinant of Korea–China relations. With the onset of the G2 era, the gap in recognition between Korean and Chinese has been reinforced, worsening the relationship between the two nations. As strategic competition has been exacerbated between China and the United States, the United States has tried to contain China by reinforcing the Korea–US relationship. Meanwhile, China has tried to reinforce its relationship with North Korea to maintain security and the status quo in the Korean peninsula and to secure a strategic buffer zone against the United States. Therefore, whenever strategic issues arise (such as nuclear weapons threats), Korea is suspicious that China takes a loose position to secure North Korea as a buffer zone by helping to maintain the current regime in Pyongyang, and China, in turn, is suspicious that Korea–US relations play a certain role in containing China.

With the emergence of the G2 era, mounting tensions between Korea and China have hampered the practical progress of these two countries’ “strategic cooperation partnership.” This study examines the popular perception of current strategic threats and diplomatic challenges in the two countries, analyzing the results of Korean and Chinese public opinion polls. Observations are presented on how such public perceptions affect the recognition of Korea–China relations. This study concludes with discussion on along what directions Korean and Chinese perception should change to promote the strategic relationship between Korea and China in the G2 era.

1)The Korea International Trade Association (KITA), available at

Ⅱ. Theoretical Discussion and Research Methods

1. Public Opinion Polls and the Study of Foreign Policy

According to constructivist theory, the most important factors that comprise social structure are not physical matters, but perceptual ones. Further, the identity of the actors and the benefits they derive in that structure are not given naturally or from the outside, but are developed through shared concepts in the society.8) From this viewpoint, the actors and structures are social entities and they are developed and reproduced through the process of mutual interactions.9) Viewed from this constructivist approach, the foreign policy of a country is not determined externally, but is composed of shared concepts in the society. Moreover, through the interactions between international society and domestic opinions, foreign policy is developed and reproduced based on socially shared concepts. From this standpoint, then, it is important to analyze the direction and characteristics of a given country’s foreign policy by way of public opinion polls.

For foreign policy issues, in which policymakers have extensive discretionary power while the general population lacks interest and professional knowledge, the role of public opinion has been a key issue. In a democracy, in which elections serve as a means for the public to control their choice of government, no policymakers can neglect public opinion. Based on this, recent studies on the subject have recognized generally that public opinion is an important factor in deciding foreign policy. For example, Richard Sobel showed through case studies that although public opinion has only a limited influence on foreign policymaking, it can constrain the scope of options and make sure policies do not stray beyond certain boundaries.10)

With this perspective in mind, there is little doubt that in a democracy system such as that of South Korea, public opinion functions as an effecting factor in the crafting of foreign policies. However, in a highly centralized authoritarian system such as China, where civil society is not well developed and civil rights are not sufficiently protected and where the public may articulate their opinions actively, there has been prevalent skepticism about whether public opinion affects foreign policy directions. However, as China achieves greater economic growth and civil society is gradually developed, the pool of actors involved in making foreign policies has continued to expand. One Chinese scholar indicates that China’s foreign policy efforts face considerable challenges due to the complexities of the social subjects that create them. He asserts that, regarding diplomatic issues, as the opinions of the government, the elite, and the public all hold significant sway, China confronts a challenge to please and appease all three.11)

In fact, for a long time since the foundation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), public opinion and policies have corresponded well in the country. As reform and open-door policies have been introduced, the Chinese people’s views on international and diplomatic issues have similarly diversified due to developments in Internet technology and the rapid development of mass media. Therefore, the influence of public opinion on foreign policy decisions has increased in parallel. The Chinese government ultimately directs its efforts to draft policies that reflect the diverse opinions of the public when important diplomatic policies are concerned.12)

The Chinese scholar Wang Wen draws upon case studies to illustrate how mass media, the reports of think tanks, and the contributions of ‘netizens’ (Internet users) have influenced public opinion and critically effected changes in China’s policies toward the United States. In early 2010, the United States’ sale of arms to Taiwan and President Barack Obama’s meeting with the Dalai Lama captured the attention of the Chinese public, fanning a strong wave of anti-American sentiment. With this kind of public support, the Chinese government reinforced its position and interrupted the China–US military exchanges. The Chinese government stressed a hardline policy against the United States and some mass media commented that China–US relations were frozen. However, on 12 March 2010, when the US Deputy Secretary of State James Steinberg expressed a soft position about the conflicts between China and the United States since 2010 through his interview with

In China, public opinion not only influences the foreign policies pursued by the government, but sometimes it leads foreign policies in more extreme directions, particularly when nationalism is aroused.14) When the tides of public opinion in China opposed Japan’s nomination as a permanent member of the UN Security Council in 2005, as evidenced by demonstrations and petition movements, the Chinese government was forced to adopt a more rigid position to show its clear stance on the issue.15) China did not officially oppose Japan’s membership to the UN Security Council initially, out of consideration for bilateral relations between the countries. However, as public opposition fiercely continued, the Chinese government backtracked and announced its official rejection of Japan’s bid for entry. In detail, on 12 April 2005 during his state visit to India, Premier Wen Jiabao said that “Japan could play a bigger role in international affairs only if it respected history, assumed responsibility for it, and regained the trust of the people of Asia and the word.”16)

Public opinion has been shown to be influential and cannot be ignored when plotting the course of China’s foreign policies. Of course, public opinion has a more limited influence when it comes to foreign policies related to the core interests of the nation. Nevertheless, one cannot deny that public opinion affects the decision-making chain that authors foreign policies. By analyzing public opinion survey data from the two countries about the public’s perception of the G2 structure in East Asia and the Korea–China relationship, this study argues that the emergence of the G2 era functions as a hindrance in establishing the strategic cooperation partnership between Korea and China.

2. Methods and Scope of the Research

The data used in this thesis is mostly derived from the results of the public opinion surveys conducted using random samplings of the Korean and Chinese populations by the Asiatic Research Institute (ARI) of Korea University and the East Asia Institute (EAI) in August and September of 2011. In addition to this main data, other available survey data about Korea China relations gathered before 2011 was also used as supplementary data. In the case of Korea, the 2011 surveys were distributed nationwide and targeted a sample population of 1,022 people (sampling error margin ±3.1% with 95% confidence level), collected randomly with respect to gender, age, and geographic area according to the registered population status as of June 2011, with a parent population of male and female respondents aged 19 years old and over. The surveys were conducted as interviews over a period of twenty days, from 19 August until 7 September 2011. In the case of China, ten major cities—Beijing, Shanghai, Chengdu, Shenyang, Xian, Guangzhou, Wuhan, Chongging, Tianjin and Nanjing, which comprise 21.3% of the total Chinese population—were chosen to provide the parent population and 1,029 samples were selected randomly in proportion to the population of each city. The surveys were conducted by telephone (fixed-line and wireless), using the random digit dialing (RDD) method with the aid of the CATI program for fifteen days from 26 August to 9 September 2011.

This article analyzes the survey results according to two categories. First, this study aims to identify how Korean and Chinese people perceive the formation of the G2 system in East Asia and how they perceive strategic threats to their national benefits due to the shift to the G2 system. Second, this study aims to identify how the people’s perception of strategic threats under the G2 system is actually reflected in Korea–China relations, and how this perception works as an impediment in current Korea–China relations.

In order to identify why the shift to the G2 system has had important influences on the development of the strategic cooperation partnership between Korea and China, the survey was designed specifically to first diagnose whether or not the Korean and the Chinese publics have identified the emergence of a so-called G2 system in East Asia. For this purpose, the surveys contained detailed questions: “Do you think the G2 system has arrived in East Asia?”; “Has the influence of China and the United States increased in Asia for the last 10 years?”; “What is your opinion of the current international order?”; and “Do you believe China will become a global leader superseding the United States?” By analyzing the respondents’ answers to these questions, it became apparent that people in Korea and China are aware that the new G2 regime has emerged in reality in East Asia.

From the survey, an analysis was then carried out on what the Korean and the Chinese people consider to be strategic threats under the G2 regime. To achieve this, the following two questions were asked and the responses analyzed: “Are China’s neighboring countries and their organizations threatening the security of China?”; and “What do you believe are the possible threats to the interest of Korea in the next 10 years?” If the Chinese respondents identified the United States as a major country that threatens the security and interests of China, and the Korean respondents recognized China as a major country that threatens the security and interests of Korea, then we could postulate that the emergence of the G2 system acts as an important obstacle to the development of the strategic cooperation partnership between Korea and China because the G2 system will reinforce the South Korea–US alliance and North Korea–China alliance.

Second, in order to identify precisely how the G2 system will influence Korea–China relations, the survey posed questions on the following concerns: China’s position about the unification of the Korean peninsula; Chinese people’s recognition about the intervention of China and the United States in the case of a crisis in North Korea; China’s behavior in case of military conflict between South and North Korea; and reinforced relations between North Korea and China. An analysis of the answers reveals that Korean people recognize that China opposes the unification of the Korean peninsula and hopes to preserve the maintenance of the current system by reinforcing its ties with North Korea, with a view to securing a favorable position vis-`avis the United States in East Asia as a member of the G2 system.

The survey results were then analyzed regarding questions concerning Chinese people’s perceptions of Koreans’ attitudes about China and the United States, and concerning popular Chinese attitudes about the relationship between North Korea and China, and the relationship between Korea and the United States. The survey questions were phrased as follows: “Which of the two countries, the United States or China, do you think Korea is nearer?”; “In case the United States and China enter into a conflict, which country will you support?” Opinions were also gathered about Chinese people’s perceptions of Korea–US relations and North Korea–China relations, and attitudes about the intervention of China and the United States in case of crisis in North Korea. Through the process of analysis, it would seem that Chinese people are aware that the strengthening of Korea’s alliance with the United States, a competitor of China, threatens the security and interests of China.

It was determined that if the results revealed that Koreans recognize that China opposes the unification of the Korean peninsula by reinforcing its relationship with North Korea, and tries to preserve the current status in Korea, and that Chinese people are aware that Korea checks China by reinforcing its relationship with the United States and threatens the interest of China, then it can be said that the competitive relationship between China and the United States is reflected in Korea–China relations. This means that the emergence of the G2 system in East Asia serves to obstruct the practical progress pursued in strategic cooperation partnership relations between Korea and China.

8)Alexander Wendt, The Social Theory of International Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), p. 1. 9)Jin-young Chung, “The Current State of Theoretical Debates on International Relations: Toward a New Synthesis?” Korean Journal of International Relations 40-3 (2000), p. 20. 10)Richard Sobel, The Impact of Public Opinion on U.S. Foreign Policy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ch. 1. 11)Peng Zhu, “Zhongguo waijiao xin tianzhan” [New Challenge of China’s Diplomacy], Huanqiu [Globe] 5 (March 2012). 12)Rui Zhu, “Waijiao juecezhongde gongzhong yulun yu meiti yinsu” [Public Opinion and Mass Media in the Process of Making Decisions of Foreign Policies], Dangdaishijie [Contemporary World] 8 (2008), p. 45. 13)Wen Wang, “Zhongguo minyide jueqi yu Meiguo yanjiude weilai” [Rising of Public Opinions in China and Future of American Studies], Contemporary International Relations 7 (2010), pp. 12-13. 14)David M. Lampton, “China’s Foreign and National Security Policy-Making Process: Is It Changing, and Does It Matter?” in David M. Lampton (ed.), The Making of Chinese Foreign and Security Policy in the Era of Reform, 1978-2000 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001), pp. 14-16. 15)Yulin Lai, “Wangluo minzuzhuyi yu Zhongguode gongmin waijiao-yi2005nian ‘fanri ruchang jianming’ weili” [Nationalism Movement on Internet and Civil Diplomacy of China: Focus on Signature Gathering Movement to Oppose Nomination of Japan as a Permanent Member of UN Security Council in 2005], Guojizhengzhiyanjiu [International Politics Quarterly] 3 (2011), p. 143. 16)Bin Ji, “Wen, Jiabao: Yazhou renmin fanri ruchang shiwei yingyin chao riben fanxing” [Wen Jiabao: Asian People’s Rejection of Japan’s Nomination as a Permanent Member of UN Security Council Should Inspire Japan’s Repentance], available at

Ⅲ. The Emergence of the G2 Era and Awareness of Korea?China Security Issues

1. The Rise of China and Popular Recognition of Changes in the International Order

Corresponding to China’s economic rapid rise, academics have paid a great deal of attention to changes in the power rankings of China and the United States since the early 1990s. While most Western scholars claim that the international order will continue to be led by the United States in the twentyfirst century,17) some posit that American power will decline and the Chinese civilization will rise again.18) In spite of these different opinions, few people seem to object to the formulation that China and the United States are regarded as the G2. While it has been stressed in China that there is no doubt that the United States is the only superpower in the world, the G2 concept has been viewed as a negative concept by most people.19) However, Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping claim that, although China is a developing country and there are differences in the power statuses of China and the United States, as the two countries have the most important bilateral relationship in the world, not only peace in the Asia-Pacific region but global peace cannot be guaranteed without the cooperation of the two countries.20) After the global financial crisis, there seem to be no particular objections in Korean academic circles to the assertion that a G2 system has emerged in the East Asia region.

How does the general public in Korea and China evaluate the emergence of the G2 structure? In order to identify if people in the two countries accept the fact that the G2 system has emerged in East Asia in reality, the three questions in the following paragraph were included and the responses were analyzed.

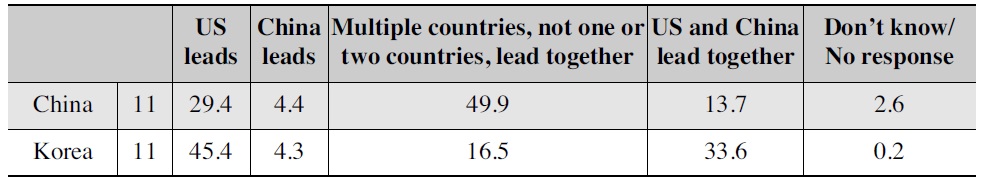

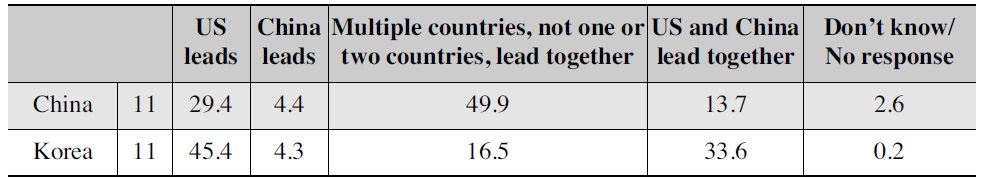

First, most people in Korea and China consider that the United States no longer leads the current international order. Although there are a few differences in the survey responses in terms of the relationship between the two countries, a low portion of the people, 50% or less, agree that the United States leads the world order (Koreans 45.4%, Chinese 29.4%). On the other hand, Chinese people gave a comparatively high rate of affirmative answers, 49.9% compared to the Koreans’ 16.5%, when asked about the formation of a multi-polar system led by many countries; 33.6% of Korean respondents answered that China and the United States lead together (compared to only 13.7% of the Chinese), and only 4.3% believe that China leads unilaterally (compared to 4.4% of the Chinese). Thus, Koreans appear to perceive the emergence of a G2 system more readily than do Chinese. However, for the question asking whether the current international order will no longer be led by the United States, 55.6% of Koreans and 69.6% of Chinese respondents agreed, indicating that people in both countries share the opinion that the existing international order, led by the United States as the only superpower, has been changed (see Table 2).21)

[Table 2.] What is your opinion on the current international order?

What is your opinion on the current international order?

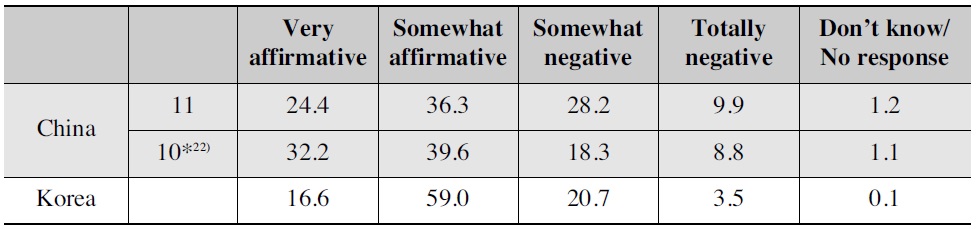

In addition, because people in both countries recognize that China will become a world leader superseding the United States in the near future, they are tacitly accepting the emergence of the competitive G2 system as a problem in the near future. As shown in Table 3, it was revealed that 60.7% of the Chinese and 75.6% of the Koreans responded that China will become a global leader superseding the United States.

Do you believe China will lead the world in the near future, surpassing the United States?

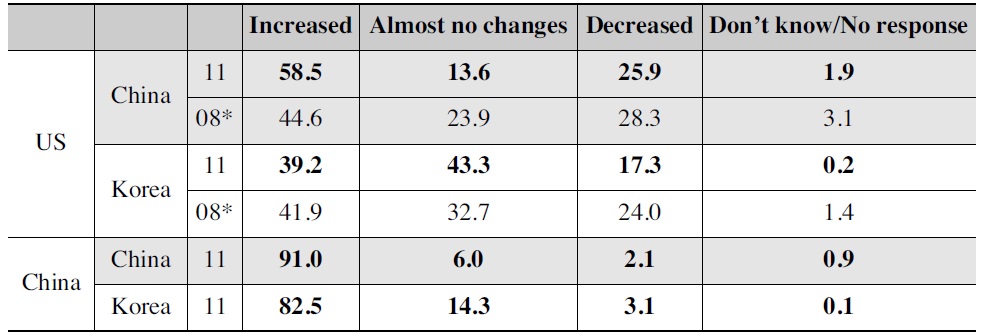

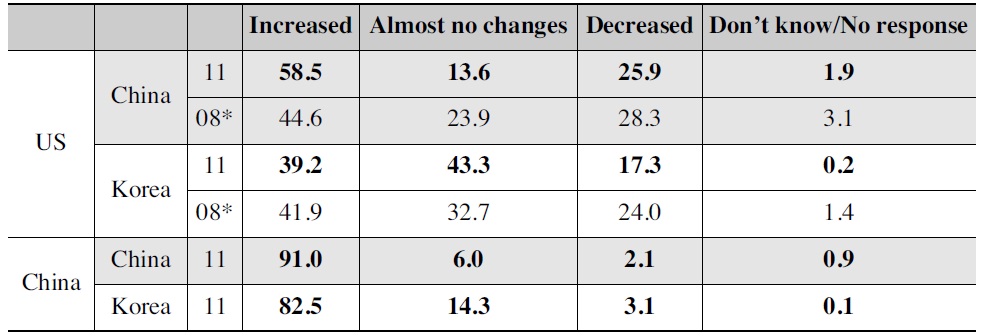

The Korean and Chinese people surveyed recognize that China will exert more influence in Asia. People in both countries appear to agree that China has increased its influence more than the United States over the last ten years (82.5% of Koreans and 91.0% of Chinese), while 39.2% of Koreans and 58.5% of Chinese people believed that the United States has expanded its influence more during the same period. On the other hand, respondents of both nationalities did not agree that China’s influence in Asia has been reduced (the rate of agreement was only 3.1% among the Koreans and 2.1% among the Chinese), while they showed comparatively higher agreement on the question that the influence of the United States has decreased in Asia (17.3% of the Koreans, 25.9% of the Chinese). This reveals that people in both countries perceive that China’s influence has grown more rapidly than that of the United States in the Asian region and that the US influence is relatively decreasing (see Table 4). According to the survey results, it can be said that people in both countries are showing recognition that the G2 system is, in fact, emerging in the East Asian region.

Do you believe the influence of the United States and China has increased in Asia over the last 10 years, or do you believe it has decreased?

In conclusion, if the survey results are indeed a representative sampling of public opinion, the majority of people in Korea and China believe that the conventional international order characterized by the uni-polar dominance of the United States has been changed to a multi-polar system or a G2 system through structural shifts. Although they do not agree absolutely on the current formation of a G2 structure, they foresee that China and the United States will emerge as competitive members of a G2 system. Moreover, if the scope is limited to the Asian region, people in both countries may be said to have accepted the fact that the era of the G2 system has already emerged.

2. The Recognition of Korean and Chinese on Security Issues

1) The Recognition of Chinese on Security Issues

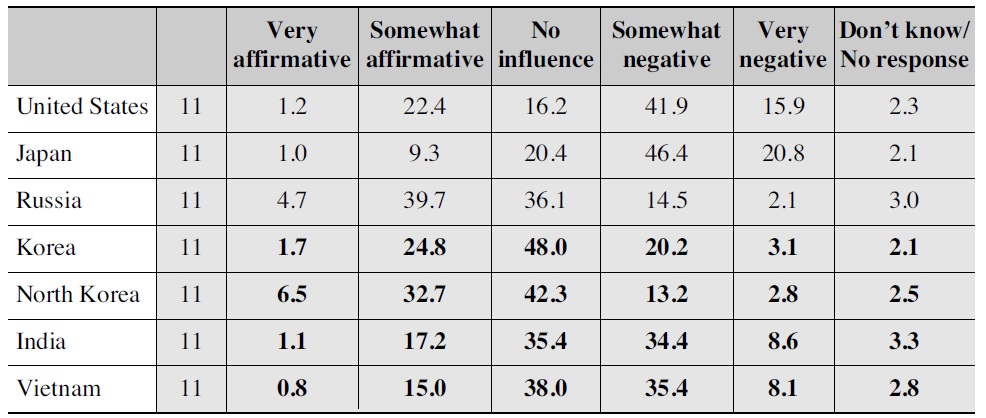

Therefore, with the inauguration of the G2 era in Asia (particularly in East Asia), what do the people of South Korea and China regard as strategic threats to their country? In analyzing answers to this question, the variables of influence that the emergence of the G2 era could exert on South Korea–China relations are examined. Specifically, to determine the factors of strategic threats recognized by China, this study canvassed opinions on the following three items.

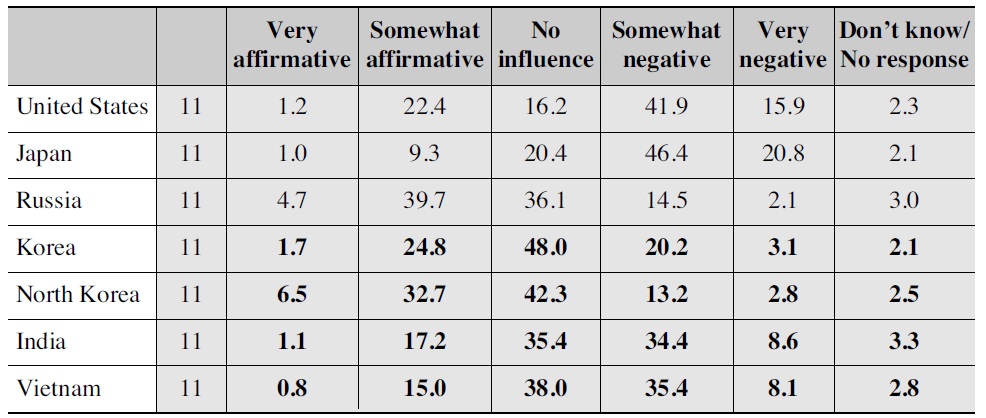

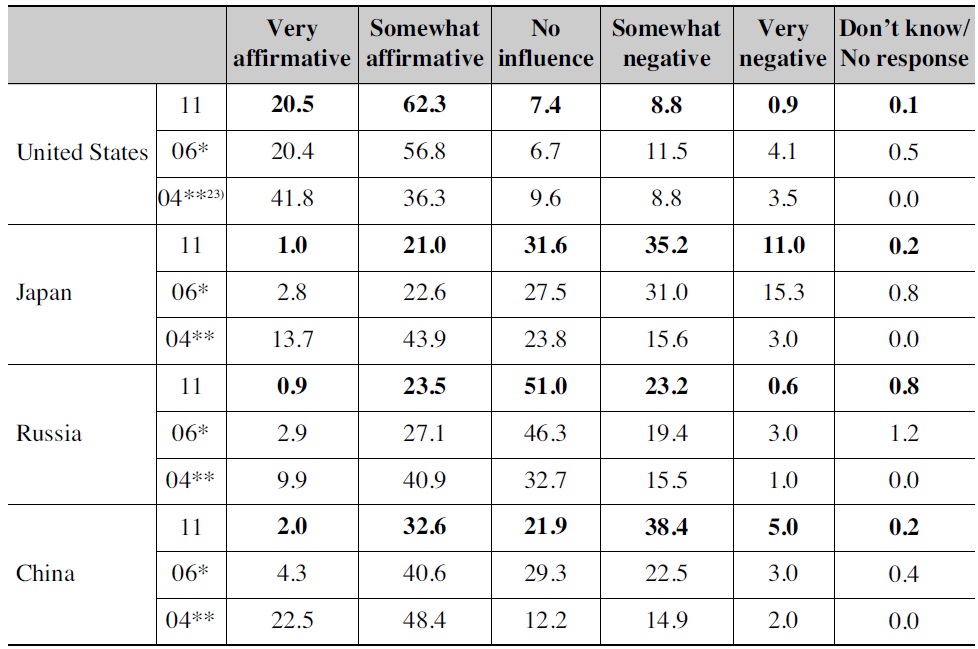

First, most of the Chinese people surveyed (67.2%) seemed to regard Japan as the nation that will exert the greatest negative influence on Chinese security, followed by the United States (57.8%), Vietnam (43.5%), India (43%), South Korea (23.3%), Russia (16.6%), and North Korea (16%), in that order. While citing Japan and the United States as the nations most likely to exert negative influences on Chinese security, the respondents surveyed indicated that Vietnam (which has an outstanding conflict with China over the Spratly Islands), and India are less likely to exert negative influences. The Chinese also seem to have fewer negative attitudes toward South Korea, Russia, and North Korea (see Table 5).

[Table 5.] What influence do you believe the following countries have on China’s security?

What influence do you believe the following countries have on China’s security?

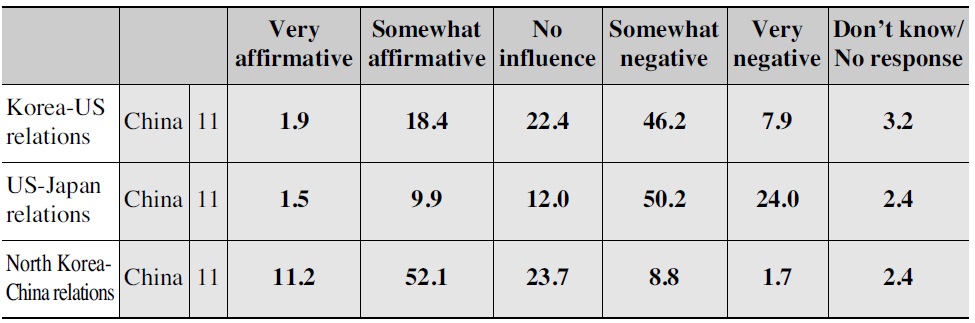

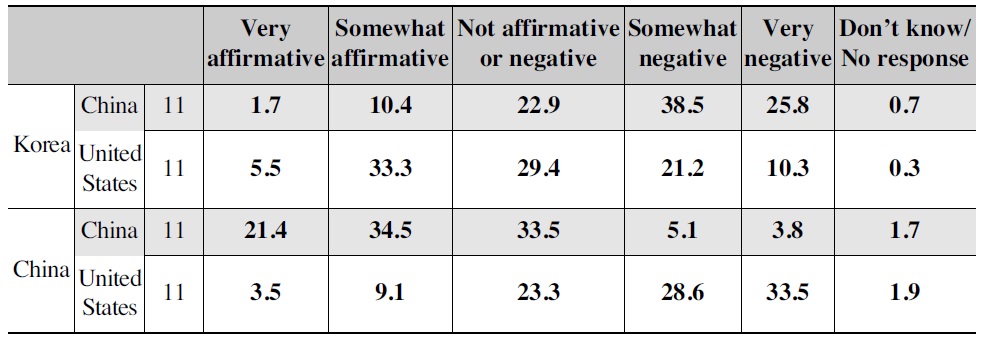

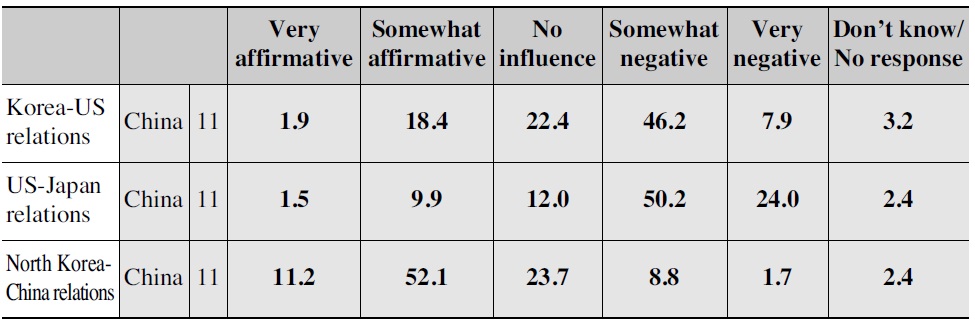

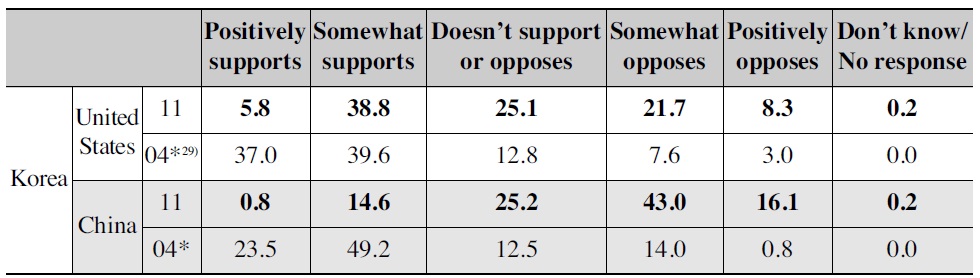

While the Chinese believe that US Japan relations (74.2%), and South Korea–US relations (54.1%) are exerting negative influences on their nation, 63.3% of the Chinese respondents see North Korea–China relations as exerting favorable influences on China. Interestingly, although the majority of the Chinese believe that South Korea and North Korea alone will not exert negative impacts on Chinese security, they forecast that South Korea–US relations would exercise negative influences while North Korea–China relations will exercise positive influences (see Table 6). This would indicate that the Chinese regard alliances involving the United States and Japan as threats to Chinese security that exert negative influences on the Chinese national interest.

[Table 6.] What influence do you believe the following relations have on China?

What influence do you believe the following relations have on China?

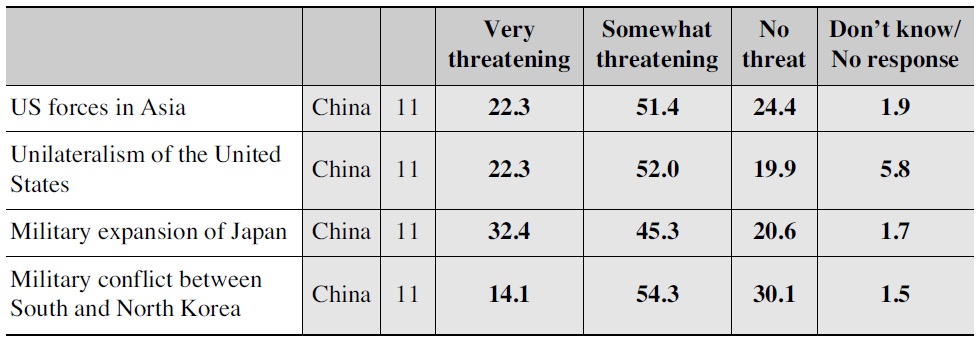

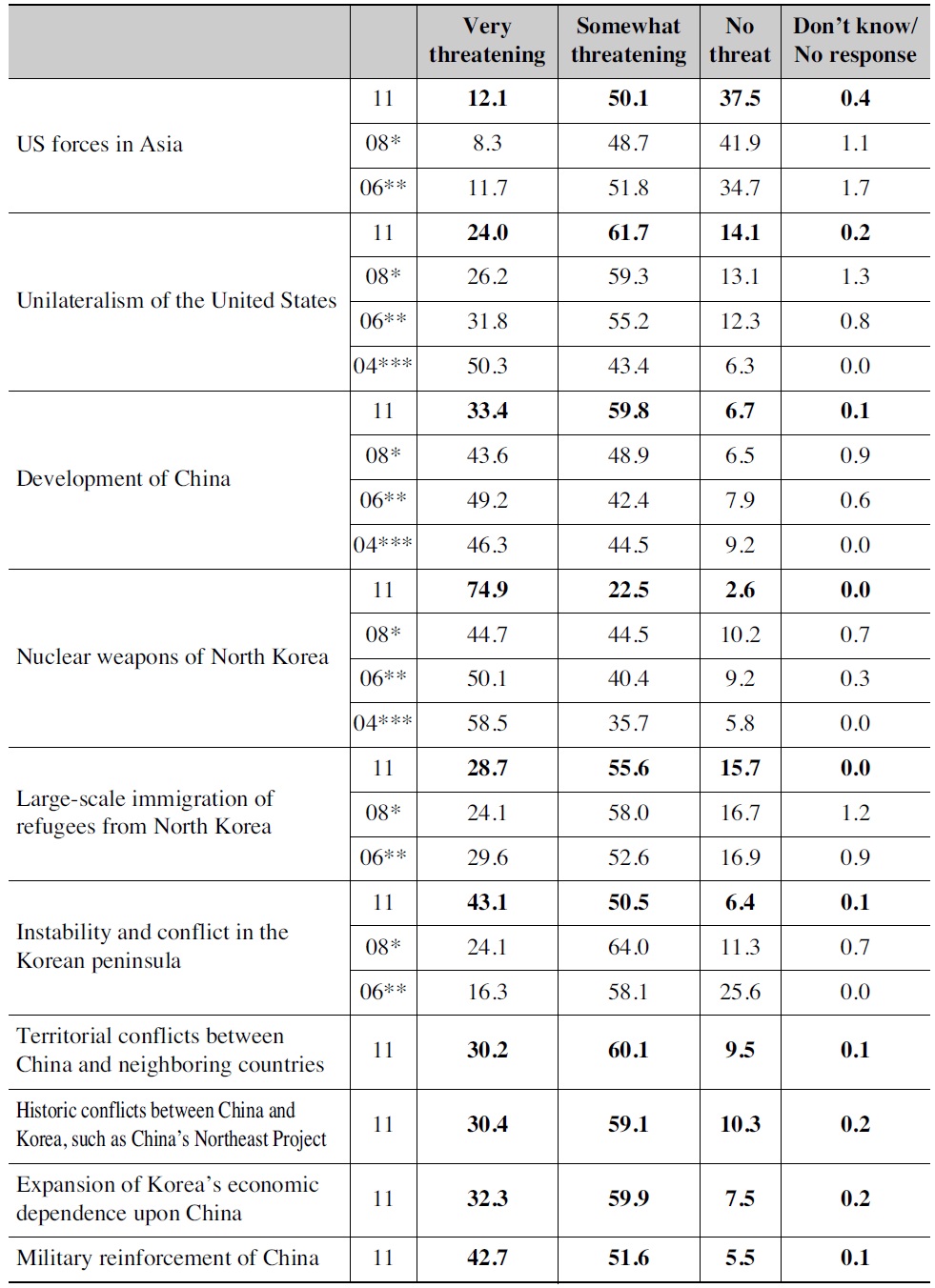

Additionally, the Chinese people pointed to the stationing of United States troops in South Korea (73.7%), United States’ unilateralism (74.3%), Japan’s militarization (77.7%), and a military clash between South and North Korea (68.4%) as potential factors that could threaten Chinese security and national interests ten years in the future (see Table 7).

The following factors may threaten the national interests of China over the next 10 years. What is your opinion about each of them?

Considering the above-mentioned survey results together, during these early years of the G2 era, the Chinese regard diplomatic alliances with the United States or Japan as factors that potentially threaten Chinese security and exert negative influences on the Chinese national interest. In addition, the Chinese regard a military clash between South and North Korea, which might well be caused by direct conflict between the South Korea–US alliance and the North Korea–China alliance, as a potential threat to their nation’s security. Accordingly, from the Chinese point of view, in the G2 era, which pits China against the United States in East Asia, the South Korea–US alliance may be regarded as a major destabilizing factor that breeds strategic mistrust between South Korea and China.

2) The Recognition of Korean on Security Issues

To analyze factors that the Korean participants regard as emerging strategic threats in the G2 era in East Asia, survey results were analyzed for the following four questions.

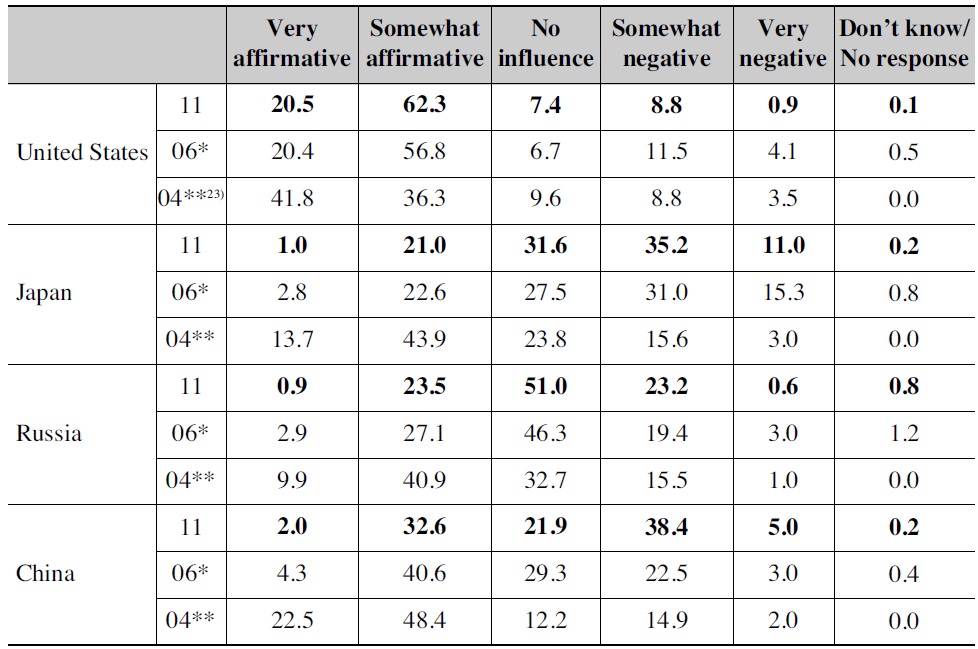

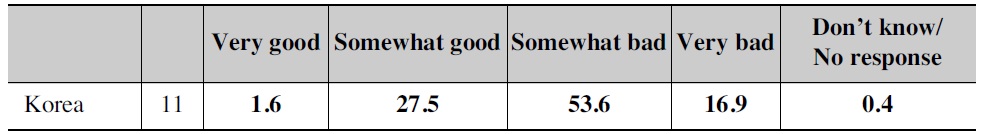

First, according to the survey data, Koreans increasingly regard Japan (46.2% in 2011, 46.3% in 2006, 18.6% in 2004) as the nation that will exert the most negative influence on the security of Korea, followed by China (43.4% in 2011, 23.5% in 2006, 16.5% in 2004), Russia (23.8% in 2011, 22.4% in 2006, 16.5% in 2004), and the United States (9.7% in 2011, 15.6% in 2006, 12.3% in 2004). Koreans regard China as the most serious threat to the security of Korea after Japan, toward which the national sentiment is deteriorating due to experiences in colonial rule, distortion of history, and issues involving ‘comfort women’. Few Koreans (under 10% in 2011) cite the United States as a threat to national interests and security. Moreover, the negative perception toward China has been increasing since 2004, which shows a general strengthening of this attitude in tandem with China’s emergence as a G2 nation (see Table 8).

[Table 8.] What influence do you believe the following countries have on Korea’s security?

What influence do you believe the following countries have on Korea’s security?

Such negative attitudes towards China on the part of Koreans can also be seen in Table 9. The majority of Koreans, 70.5%, replied that they would feel repulsion if China became an Asian leader, showing their unfavorable attitude towards China’s rise as a leading nation in Asia.

[Table 9.] How do you feel about the possibility that China will become a leader in Asia?

How do you feel about the possibility that China will become a leader in Asia?

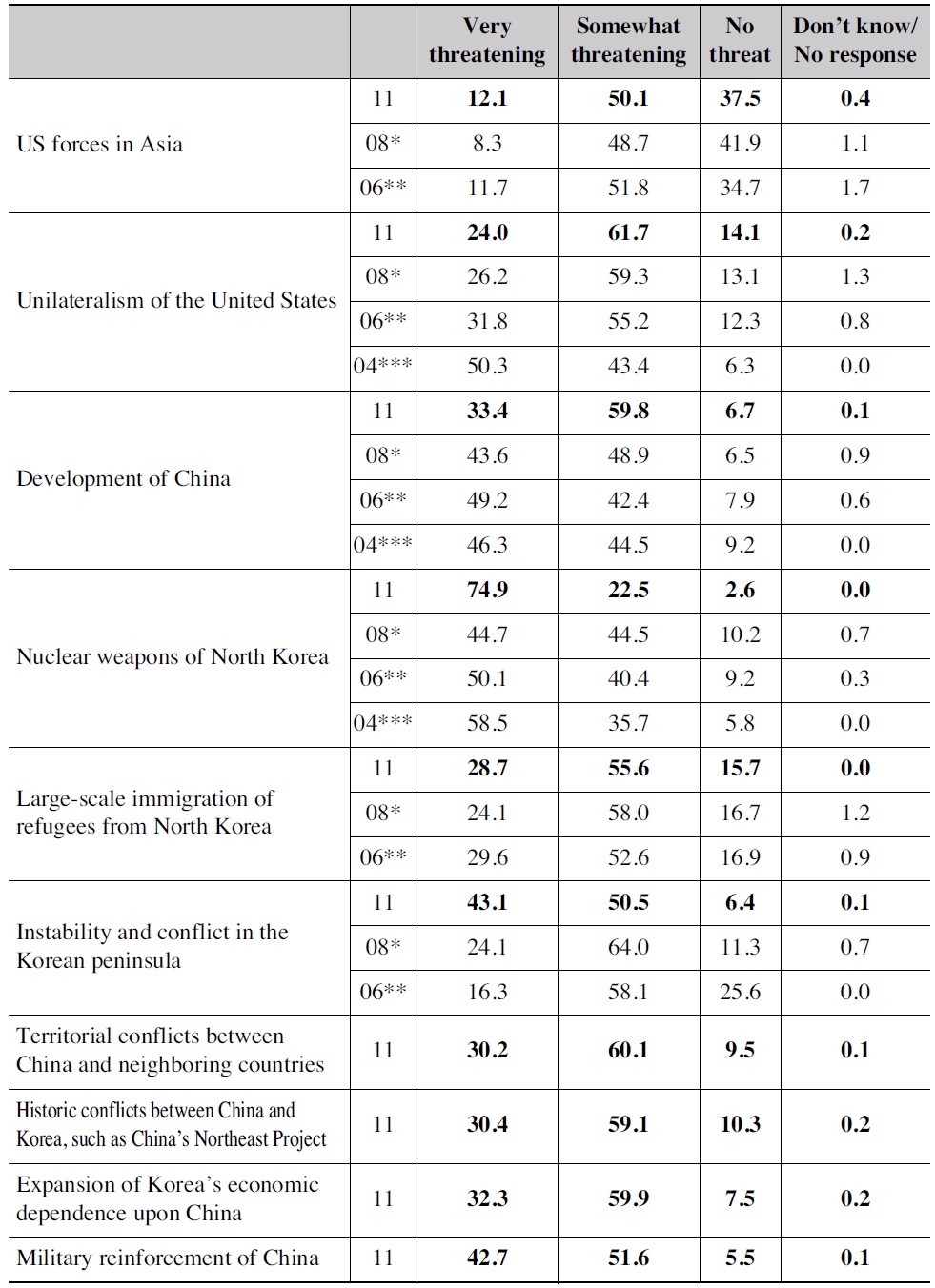

The Korean respondents perceived the following factors as threatening their national interest within ten years: the stationing of United States troops in South Korea (62.2% in 2011, 57% in 2008, 63.5% in 2006); United States unilateralism (85.7% in 2011, 85.5% in 2008, 87% in 2006, 93.7% in 2004); China’s development (93.2% in 2011, 92.5% in 2008, 91.6% in 2006, 90.8% in 2004); the North Korean nuclear arsenal (97.4% in 2011, 89.2% in 2008, 90.5% in 2006, 94.2% in 2004); a large-scale immigration of refugees from North Korea (84.3% in 2011, 82.1% in 2008, 82.2% in 2006); instability and conflict on the Korean peninsula (93.6% in 2011, 88.1% in 2008, 74.4% in 2004); territorial disputes between China and nations in the vicinity (90.3%); historical conflicts between Korea and China including the Chinese Northeast Project (89.5%); increasing dependence on China by the Korean economy (92.2%); and China’s military buildup (94.3%) (see Table 10). The Korean respondents identified all the survey items as threatening the security of South Korea. It could therefore be said that the Koreans generally regard the Asian policies of both China and the United States, the North Korean nuclear problem, and instability and conflict on the Korean peninsula as factors threatening their national interest. In particular, threatening factors connected with China account for a larger portion (over 90%) in almost all survey items. This suggests that the Koreans are feeling strongly threatened by an emerging China, by the instability caused by the strategic rivalry between China and the United States in Asia, as well as by the North Korean regime and its nuclear weapons capacities.

The following are possibilities that may threaten the national interests of Korea over the next 10 years. What is your opinion about each of them?

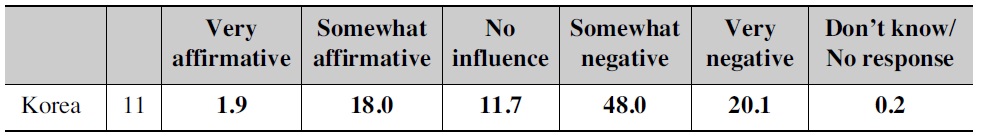

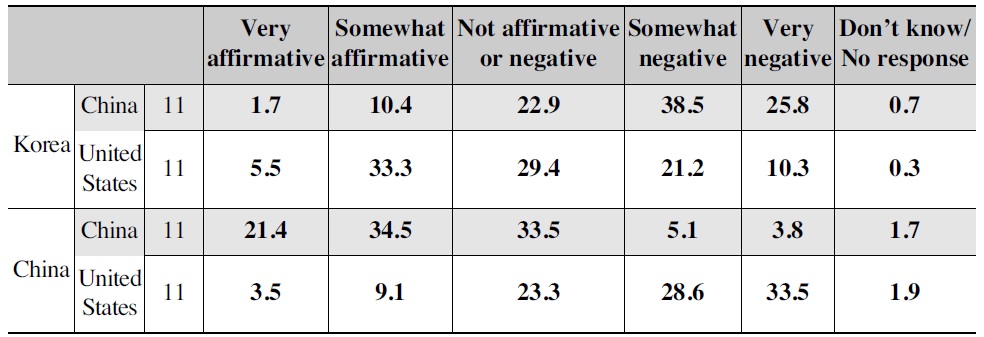

The Koreans therefore believe that the rise of China, its rivalry with the United States, and the problems associated with North Korea are significantly menacing the security of their nation. Therefore, distrust of the Koreans toward China is likely to only be further strengthened in times when China acts to solidify its relations with North Korea. Table 11 illustrates this Korean attitude. In Table 11, 68.1% of the Koreans surveyed replied that strengthening North Korea–China relations would exert negative influences on the security of Korea. This directly contrasts the findings presented in Table 6, in which the Chinese evaluate North Korea–China relations very positively.

What influence do you believe the reinforcement of the relationship between North Korea and China will have on South Korea’s security?

As mentioned above, the Koreans express a certain wariness toward the emergence of China, China’s strategic competition with the United States in Asia, and North Korean problems including nuclear issues. They feel that if China strengthens its ties with North Korea against South Korea and the South Korea–US alliance, the security of Korea could fall into crisis. Accordingly, the Chinese policy toward South and North Korea, North Korea–China relations (from the viewpoint of South Korea), and South Korea’s policies and alliance with the United States (from the viewpoint of China) may all be regarded as major factors that work to strengthen distrust between South Korea and China.

17)John G. Ikenberry, “The Rise of China and the Future of the West,” Foreign Affairs 87-1 (January-February 2008); Joseph S. Nye Jr., “China’s Rise Doesn’t Mean War,” Foreign Policy 184 (January February 2011). 18)Niall Ferguson, “Korea, Wishing Balance of the U.S. and China,” Chosun Ilbo (13 February 2012). 19)Chunyuan Li and Jianzhong Fan, “Meiguo shuailuolun xilun” [Analysis of US Demise Theory], Xiandai guoji guanxi [Contemporary International Relations] 8 (2008), pp. 30-36; Niu Xinchun, “ZhongMei lianyan qi shishi yige tao” [Relationship of the US and China, as Set in Reality], Huanqiu Shibao [Global Times] (16 December 2008); Liu Weidong, “G2, ‘ZhongMei’ yu ZhongMei guanxide xianshi dingwei” [G2, ‘Chimerica’ and Practical Crisis of China–US Relations], Hongqiwengao 13 (2009), p. 8; Liu Weidong, “G2: meilide pengsha” [G2: Beautiful Closure], Friend 5 (2009), pp. 38-39. 20)Premier Xi Jinping, “The United States and China Are the Two Powerful Countries on Both Sides of the Pacific,” Joongang Ilbo (15 February 2012); Shi Yinhong, “ZhongMeizhiju, Chongxin fapai” [The United States and China, Move Anew], Zhongguo jingji zhoukan [China Economic Weekly] 1 (2010), pp. 11-12. 21)Survey results of Korea scholars indicate that 67% of Korean scholars considered that the current international order is a multi-polar system (39.4%), G2 system (26.6%) or that China leads (1%) and only 32% said the United States leads the international order. On the other hand, 55.6% of the general public marked these items, revealing that scholars have a greater preference for the multi-polar system compared to the public. 22)The question in 2010 survey was “equivalent to the United States.” 23)In the case of the 2004 survey, the questionnaires had five response levels: from “Very useful” to “Very threatening.”

Ⅳ. The Coming of the G2 Era and Aggrandizement of Strategic Discredit between Korea and China

What influence is the emergence of the G2 era exerting on Korea–China relations? Is the new arrangement fueling the strategic and cooperative relationship between the two nations, or is it calling the soundness of the countries’ bilateral relations into question? To investigate these matters, two variables that might affect Korea–China relations were studied to determine how they are reflected in Korea–China relations: the Chinese policy toward North and South Korea and North Korea–China relations, and the Korean policy toward the United States and the Korea–US alliance.

With the emergence of the G2 era in East Asia, competition between China and the United States in the region is intensifying. The competition between the two powers became a fully-fledged rivalry since United States began to return to East Asia in 2010.24) Until then, China had expressed their determination to become the strongest nation in the world through a ‘soft’ rise to power, without resorting to war. China has been pushing ahead with relatively passive foreign policy, placing its focus on promoting economic development as a socialist developing country, while simultaneously exerting efforts to secure the conditions needed to become a strong nation.25) However, tension-ridden relations between China and United States have developed since the United States began to return to East Asia in 2010, pressing China from all ranges of fields.26) One Chinese scholar points out that the American reappearance in Asia will heighten tensions in the Asia-Pacific region, as China first wants to be a strong nation in that area before it becomes a global power.27)

Based on Chinese scholars’ views on the return of the United States to East Asia, China is expected to respond assertively.28) Therefore, the direction of China–US relations will exercise important influences not only in the East Asian context, but also on the future of the Korean peninsula. An acceleration of the contest for hegemony between the China and the United States will make the alliance of the Korean peninsula and Korea–US relations even more strategically important from the perspective of the United States. For China also, the Korean peninsula is emerging as a core interest, along with the Formosa Strait and the South China Sea. This means that the strategic importance of North Korea is correspondingly expanding, making the unification and security architecture of the Korean peninsula a key strategic issue. In this situation, China may strengthen its concerns that Korea will join the United States to keep check on China, and Korea may, in turn, have greater suspicions that China will consolidate relations with North Korea to secure its strategic buffer zone, and will object to the unification of the Korean peninsula out of a preference to preserve the status quo.

What perceptions do the people of the two nations have on these issues? This study utilizes survey results detailing Koreans’ perceptions of what Chinese people think about the unification and North Korean issues, regarded by the Korean people as central national security issues. The data analysis attempted to determine the Korean people’s perception about China, as one of the G2 nations, seeking to reflect its strategic interests in its policy on the Korean peninsula. The concrete survey items include: Chinese stance on Korean unification; the Chinese perception of possible Chinese intervention during a North Korean regime crisis; Chinese attitudes toward military conflicts between North Korea and South Korea; and others.

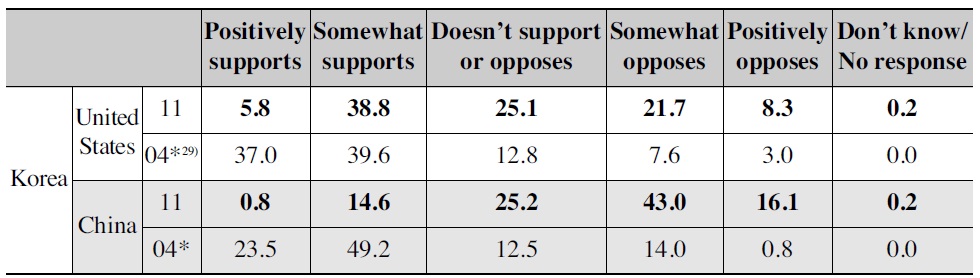

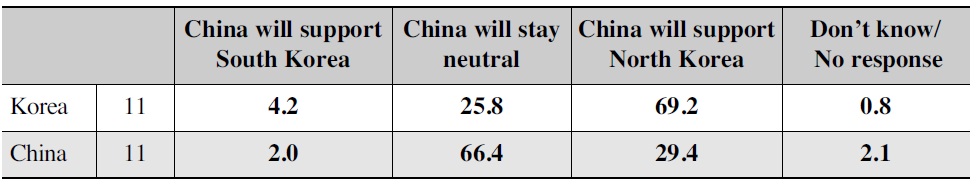

First, a high percentage of Korean survey respondents perceive that China will object to the unification of Korea. Consulting Table 12 below, the ratio of Koreans who believe that the United States will support Korean unification (44.6 % in 2011, 76.6% in 2004) is higher than the percentage of respondents who believe China will support Korean unification (15.45% in 2011, 72.7% in 2004). In addition, it was revealed that Koreans do not tend to concur with the Chinese survey respondents’ views on the subject of the unification of the Korean peninsula. Table 13 shows that in 2011, 36.7% of the Chinese responded that they were willing to see the unification of Korea, while only 10.9% replied that they objected to it. In contrast, 15.4% of the Koreans surveyed replied that they believe China supports the Korean unification, and 59.1% of the Koreans replied that they see China wholly against Korean unification. This shows that the Koreans maintain the perception that China, in its competitive relations with the United States, prefers a status quo on the Korean peninsula and objects to its unification out of concern for its strategic interests.

What position do you believe the following countries have about the unification of the Korean peninsula?

[Table 13.] What is your opinion on the unification of the Korean peninsula?

What is your opinion on the unification of the Korean peninsula?

Such a perceptual gap between Korean and Chinese respondents is also seen in their views on Chinese intervention in the case of a possible North Korean regime crisis. According to Table 14, 12.1% of the surveyed Koreans replied with affirmative feelings toward the idea of a Chinese intervention, while 64.3% expressed negative attitudes. In contrast, the Chinese showed different views. Of those surveyed, 55.9% replied that they were in favor of a Chinese intervention in North Korea, while only 8.9% reported a negative response.

What is your opinion on the intervention of the United States and China in the event that the North Korean regime suffers a serious crisis?

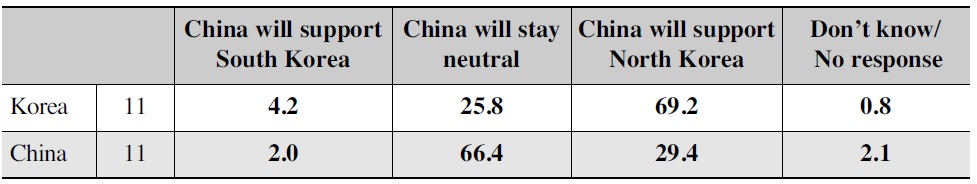

A total of 69.2% of Koreans replied that, if a military clash were to erupt between South and North Korea, they were of the opinion that China would give aid to North Korea; only 4.2% replied that China would support South Korea. Such results, if representative, confirm that the majority of Koreans believe that China will support North Korea out of their own national interest. The Korean perceptions widely diverged from the views expressed in the Chinese subjects’ surveys. In fact, 2.0% of the Chinese respondents replied that China would support South Korea and 29.4% replied that China would support North Korea. The considerable gap (39.8%) between the ratios of the people in the two nations who replied that China would choose to support North Korea shows that the Koreans have strong doubts that the Chinese, regardless of their expressed views, will in reality support North Korea (refer to Table 15).

How do you believe China would act in the event that South and North Korea clash militarily?

As corroborated in Table 12, the negative attitudes held by the Koreans toward the Chinese support of North Korea stems from their perception that strengthening North Korea–China relations will have negative influences on South Korean security. Table 11 shows that 19.9% of the Koreans surveyed replied that strengthening North Korea–China relations would have a positive effect on the security of South Korea, while 68.1% replied that it would have a negative effect.

Taking into consideration all these findings, the Koreans believe that China, competing with the United States in East Asia, opposes the unification of the Korean peninsula for the benefit of their national interests and will try to strengthen its relations with North Korea and support the status quo by maintaining the North Korean regime.

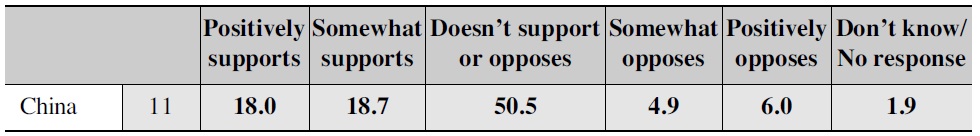

Therefore, what perceptions do the Chinese people have toward South Korea and its relationship with the United States? To study this, the Chinese attitudes toward the South Korea–US alliance, and the presence of US forces in South Korea were analyzed. The survey results are derived from detailed questions: “Which country do you think is more closely related to Korea: the United States or China?”; “How do you believe Korea should act in the case of a serious conflict between the United States and China?”; and “Do you believe the United States would support South Korea militarily in the event that North Korea was to invade South Korea?”

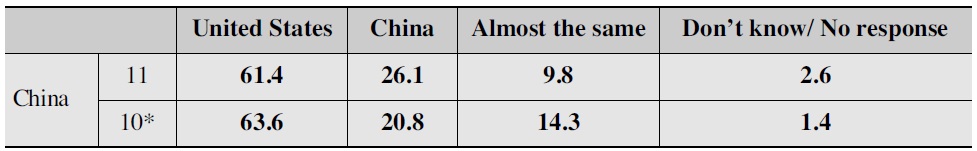

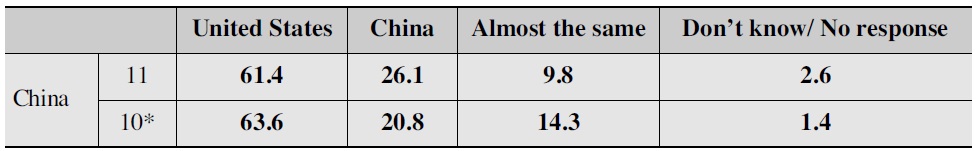

First, the Chinese believe that South Korea is far closer to the United States than to China. As indicated in Table 16, the majority of the Chinese surveyed (61.4% in 2011, 63.6% in 2010) think that Korea is nearer to the United States than to China. The ratio measured in 2011 was higher than in 2010, when tensions arising from the sinking of the ROKS Cheonan warship deepened between South Korea and China.

[Table 16.] Which country do you think is more closely related to Korea: the United States or China?

Which country do you think is more closely related to Korea: the United States or China?

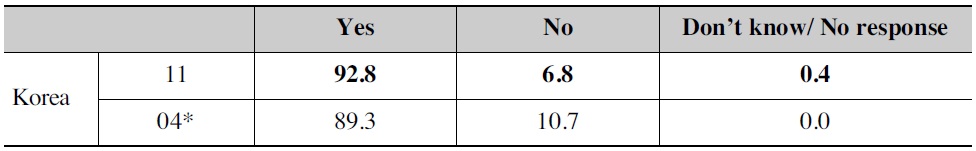

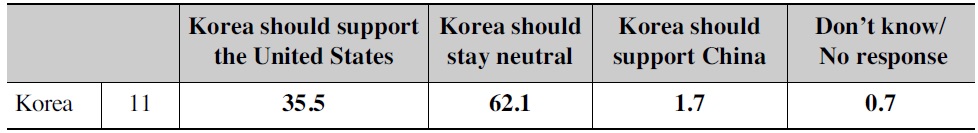

The perception of the Chinese does not seem to fundamentally differ to the perception of the Koreans themselves. Overall, 35.5% of the South Koreans surveyed replied that South Korea should support the United States in the event of China–US conflict, while only 1.7% replied that South Korea should support China (see Table 17). Nonetheless, the Chinese have a stronger belief that South Korea is closer to the United States than South Koreans believe, which shows the deep mistrust of the Chinese toward South Korea–US relations. In Table 17, 35.5% of Koreans responded that South Korea should support the United States in the case of a US–China conflict, while only 62.1% said that South Korea should remain neutral.

How do you believe Korea should act in the case of a serious conflict between the United States and China?

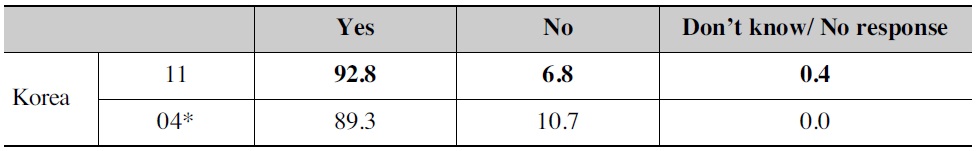

The Koreans’ strong confidence in the United States can also be confirmed in the survey responses showing the belief that the United States would support South Korea militarily in the event of a military clash between South Korea and North Korea. In Table 18, 92.8% (89.3% in 2004) of the South Koreans believe that if North Korea were to invade South Korea, the United States would militarily support their cause. These responses are major grounds for the Chinese belief that South Korea is strategically nearer to the United States.

Do you believe the United States would support South Korea militarily in the event that North Korea was to invade South Korea?

Therefore, the Chinese believe that United States Japan relations (74.2%) and South Korea–US relations (54.1%) exert negative influences on China’s security, while 63.3% believe that North Korea–China relations have positive influences (refer to Table 6). The Chinese also have negative perceptions toward a US intervention should the North Korean regime experience a time of crisis; however, the respondents also show a largely affirmative view toward Chinese intervention in this same instance. As illustrated in Table 14, 12.6% of the Chinese replied that a US intervention would be seen affirmatively while 62.1% replied negatively. In contrast, the Koreans were less negative toward the idea of a US intervention in comparison with the Chinese, with 38.8% replying affirmatively and 31.5% negatively.

To summarize, the Chinese largely believe that the South Korea alliance with the United States could harm Chinese national interests, while Koreans fear that China regards North Korea as a strategic buffer zone, necessary for competing with the United States and that China will try to strengthen its bilateral relations with North Korea and object to the unification of the peninsula. Such sources of distrust are assumed to result from the growing strategic importance of South and North Korea due to the fierce competition between the United States and China in East Asia.

24)Hillary Clinton, “America’s Pacific Century,” Foreign Policy (November 2011), pp. 57-63. 25)Bingguo Dai, “Jianchi zhou heping fazhan daolu” [Peaceful Way to Development Must Be Taken] (6 December 2010), available at

It is generally accepted that, in a democratic country, public opinion plays a role as a determinant of foreign policy changes. In China, it was once deemed that the effects of public opinion on Chinese foreign policy were negligible. Now, however, as the country’s civic society develops along with its economic growth, the public’s say on a wide range of policy issues has become a major factor to consider in the process of government policymaking. In particular, the general public, who have expressed their pride at the idea of an emerging China on the international scene, are expressing keen interest and presenting their opinions on various diplomatic issues. The formation and expression of such public opinions have wielded greater power and gained momentum due to the development of the Internet. Now, political leaders are starting to regard public opinion as an important factor that should not be neglected when crafting foreign policies. Therefore, it is very meaningful to analyze the influence of the emergence of the G2 era and its dynamics on South Korea–China relations by assessing public opinion surveys conducted in the two nations.

With the ongoing emergence of the G2 era, the strategic competition between China and the United States has intensified. According to the present analysis of the survey results, the Koreans feel a serious threat posed by the Chinese rise to power and the subsequent strategic competition with the United States in East Asia and the North Korean nuclear weapons issue. They see a possibility that China will oppose South Korea and the South Korea-US alliance by strengthening ties with North Korea, thereby posing a threat to the security of South Korea. On the other hand, the Chinese perceive the US policy toward Asia and the South Korea–US alliance as a potential threat to the security of China.

The Koreans believe that China is pushing for a policy advocating the status quo on the Korean peninsula, opposing the unification of Korea and strengthening relations with North Korea in order to exploit the Korean peninsula as a strategic zone against the United States. On the other hand, China does not trust South Korea in that it sees its neighbor as strengthening relations with the United States in an effort to check the rise of China in East Asia. Such mistrust is the typical scenario considering the greater strategic importance of South and North Korea in the midst of the intensified China United States rivalry in East Asia.

Such bilateral strategic mistrust is intensifying as China is rapidly emerging and the United States has started to check China in line with its return to East Asia following the global financial crisis in 2008. As a result, the South Korea–China relationship is somewhat deadlocked due to these external issues, though the bilateral relationship between the countries themselves has been upgraded to the level of strategic partnership since 2008. This situation has wholly prevented the strategic partnership from materializing concrete results.

To affect concrete results from the strategic partnership between South Korea and China, efforts should be made to diminish the negative perceptions concerning the relationship. Until now, the bilateral relations have been brisk only in the sense of economic and cultural exchanges, while concrete development was not facilitated in the field of political and military security. Therefore, in order to expand the scope of actual exchanges and cooperation in the area of political security, efforts that diminish bilateral distrust on strategic issues are urgently needed.

To strengthen strategic mutual trust, China should first discard the perception that the strengthening of the South Korea–US alliance is aimed at checking China’s emergence; at the same time, South Korea should make efforts to address public misconceptions and mistrust of China.

Second, China should transform its perception to see that Korean unification will not harm Chinese strategic interests, but rather contribute to promoting peace and prosperity in East Asia. South Korea, on its part, should make efforts to give confidence to China that a unified Korea will not be a threat to China.

Third, Korea should realize that the Chinese rise to power need not pose a threat to Korea, but rather provide the country with opportunities. It should see China’s emergence to the G2 in East Asia as a reality, and thus encourage China to play the role of a regional power to secure stability and peace on the Korean peninsula and in East Asia.

Beyond this, South Korea should make a number of efforts to facilitate the progress of South Korea–China relations. First, it should attempt to manage China–United States relations on a stable and permanent basis. Korea should thus be keen to avoid a situation in which the Korean peninsula triggers a diplomatic clash or open conflict between United States and China, and in which South Korea is forced to choose one side over the other. Korea should make efforts to form a desirable environment for its own security and unification by preventing the Korean issue from becoming the origins of a final showdown between China and the United States, promoting dialogue and cooperation between South and North Korea and enhancing its diplomatic independence.

Next, South Korea–China relations and South Korea–US relations should be developed so that they do not follow the dictates of zero-sum games. To achieve this purpose, while keeping the South Korea–US alliance intact, efforts should be made to facilitate actual points of cooperation for the strategic partnership between South Korea and China.

Third, when strengthening cooperative relations between North and South Korea, China, and United States, the specific influences of such activities on the Korean peninsula need to be compensated for and duly considered. While China and the United States remain pitted against each other, and South and North Korea are in conflict, China is likely to maintain a strong alliance with North Korea in an effort to pit this alliance against the South Korea–US alliance. Such a situation is quite possibly the worst scenario if peace is desired in Northeast Asia, and would result in deepening the two Koreas’ dependence on China and the United States.

Fourth, a multilateral consultation forum in the form of a tripartite system should be activated in East Asia to serve as a catalyst for securing Asian security and cooperation. Long-term efforts should thus be made to establish a multilateral consultative body for securing peace and prosperity in East Asia.