1. When Memory Became Portable, Memes Rose

Cognition, a derivative of the Latin,

In the course of evolution, specialized structures developed that connect the programmed memory to learned memory, and learned memory to each other, which we call the nervous system. The brain evolved as a specialized organ dedicated to processing memory, both learned and intrinsic (DNA), which in turn facilitated learning, survival, reproduction, and further enlargement of the brain. Learning through trial and error created memories that facilitated individual and species survival, and resulted in building bigger brains, but the memories themselves died with the organism until the brain developed imitation as a learning tool.

With imitation, which is robustly in evidence in primates and in songbirds (Goodall, 1964; Haesler, Rochefort, Georgi, et al, 2007; Heyes, 1998; Heyes & Galef, 1996; Pinaud & Terleph, 2008; Premack & Premack, 1994; Sugiyama, 1995), learned behavior (memory) could be transferred from one brain to other brains in the form of memes. The term, meme, was coined by Dawkins (Dawkins, 1976; Dawkins, 2006), who proposed the term to denote information that is replicated through imitation. Memes have been elaborated by Blackmore, Dennett, and others, and there is considerable controversy concerning exactly what memes are (Aunger, 2000; Aunger, 2002; Blackmore, 1999; Bloch, 2000; Boyd & Richerson, 2000; Crofts, 2007; Distin, 2005; Gleick, 2011; Kronfeldner, 2011; Kuper, 2000; Leigh, 2011; Leland & Odling-Smee, 2000; Sperber, 2000). There are different views on whether the meme is information, specific neural structures, objects such as paintings, etc., or maybe all or none of these. I consider the meme to be information in a broad sense (Gleick, 2011), which can be represented (contained) in neural structures, natural and man-made objects, electronic codes, etc. Inherent in the term, meme, is the implication that the information is replicable. For a comprehensive discussion on the nature and usefulness of memes, see Blackmore (Blackmore, 2010). The purpose of this paper is not so much to review controversies in memetics but to show how the concept may be fruitfully applied to mental health and illness.

In biologic terms, meme is portable memory, or brain state that can be communicated. Memes are whatever can be communicated, and therefore reproducible, however inexactly, in another information processing entity, usually the brain. This reproduction need not occur immediately, the memes may lie dormant in books or chiseled images on cave walls for centuries before they come alive again (perceived and processed) and are reproduced in another brain. Memes may arise autochthonously from experience, then broadcast to outside. There is considerable confusion about whether memes are physical entities or not. Memes are physical entities to the extent that memes can only exist and be transmitted as physical entities, but like genes, what they represent may not be readily describable physically – such as resilience, dominance, intelligence, esthetic sense, attractiveness, rationality, etc. I further submit that memes as portable memory may also contain an emotional component, i.e., memory of emotion. Thus, the image of a bear that almost attacked you is a meme, as is the fear you experienced that was associated with the image. And you can describe it in written language so that another person may share your experience, or you can verbally describe the scene and show facial expression that shows how you felt, which will be transmitted by mirror neurons to another person. The whole scene can be videotaped, and played to audiences who have never known you. Memes, like genes, are usually transmitted and replicated in combinations (sometimes called memeplexes) which tend to enhance the strength and viability of the combined memes.

An important aspect of the concept of memes as proposed by Dawkins is that memes are replicators like genes, and undergo Darwinian natural selection. (Blackmore, 2000; Blackmore, 1999; Dennett, 1995; Gleick, 2011)

2. Co-evolution of Brain, Memes, and Language

It is well known that humans have the largest brains relative to weight among all animals. The brain size of early hominids up to about 2.5 million ago was not much larger than present day chimpanzees, but it grew rapidly with the transition from

Susan Blackmore proposed that a turning point in evolution occurred with the advent of memes, i.e., memes changed the environment in which genes were selected, and that the direction of change was determined by the outcome of memetic selection (Blackmore, 1999). She argues that genes were selected for bigger and bigger brains in humans because of the selective advantage of memes. What sets

Prior to the advent of language, memes were mostly memory residing in individual organisms and died with the organisms. Chimpanzees could observe a bright chimpanzee cracking a nut with a stone, and this information could spread, but only to a limited degree. First, they had to be in visual contact with the bright chimpanzee, and second, the bright chimpanzee must engage in the behavior for the meme (how to crack a nut) to spread, and this presupposes that there are nuts and stones around. If chimpanzees had language, one who observed the behavior could describe it even when there were no nuts and stones, and such a meme could spread much faster and wider. Such was the case with

At a certain level of complexity of the brain, ideas or concepts arose. An idea is a meme derived from processed memes (memories), i.e., an abstract meme. Ideas can be communicated to another either through imitation, emotional expression, words, or other means of communication. For example, an animal may cry out at the sight of a predator, and others who have not seen the predator may get the idea that there is danger and flee. Some ideas are gene-derived within an individual’s brain, others are memes from outside that took up residence in the individual’s brain. Ideas, as memes, are infectious in various forms – written words, songs, movies, DVDs, etc. There is some controversy in memetic circles concerning whether memes are physical entities or not. (Aunger, 2000; Aunger, 2002; Bloch, 2000; Boyd & Richerson, 2000; Kronfeldner, 2011; Kuper, 2000)

I consider memes to be information, which always exists in physical form, be it as enhanced neural connections in the brain or patterns of ink on paper. Memes are like genes in that they are physically encoded, but genes make sense only when expressed – i.e., as phenotypes which are subject to natural selection. Some confusion rises because memes, as information, are like both genes themselves (recipe) and phenotype (meal). Memes as phenotype are subject to natural selection. Memes, like genes, undergo mutation and copying errors. Differently encoded memes may result in similar phenotype memes, and, as information, phenotypic memes, unlike genes, can be encoded in different language and in different media. Inherent in the concept of memes is that they are replicators and undergo Darwinian natural selection, both in the brain (as we will see in the next section) as well as outside the brain in what we call culture. While memes consist of information, the term, information, lacks this connotaation.

In the process of human evolution, the brain’s capacity to contain memes improved and so did the pace of evolution of memes within the brain. There is, however, a limit to how large human brain can become given the genes of mammalian evolution. Memes within one brain die with the brain. Memes had to find ways of sending copies outside of the brain in a reliable way and also to reside outside of the brain until it can infect other brains.

With the development of written word, memes found an abode outside of brains. Now they could reside in patterns of indentations in clay, stone, and of dye on paper, and eventually as electronic signals in magnetic tapes and optical media. Now, more memes reside outside of human brains than inside them, in printed form in libraries and homes, in electronic media, and in digital form in computers, CDs and DVDs, and in the cloud. The acquisition of language by

Memes are being thrust into the cosmos outside of planet earth – intentionally as in the golden disk in the spacecraft Voyagers I & II which are speeding toward the stars, and not-so-intentionally in the form of radio waves containing TV and radio signals leaking outside the earth.

3. Neural Memes and Natural Selection

How are memes actually stored in the brain? Kandel and colleagues showed how new experience becomes long-term memory by forming new neural connections (Kandel, 1979; Kandel, 2009). Such newly formed neural connections, as memes, interact with existing neural connections (which may be themselves acquired memes, or DNA-derived memes), forming neural clusters with enhanced connections, forming a neural code, which represents a meme complex, i.e., information that is connected and potentially processed as a unit. Such neural codes may be represented as binary codes (Lin, Osan & Tsien, 2006; Tsien, 2007).

How exactly is a meme reinforced or attenuated in the brain? Kandel described a sequence of events in long term memory formation. With repeated stimulus of a neuron, a sequence of chemical reactions causes gene activation in the nucleus of the neuron, resulting in release of messenger RNA in a dormant form. Further stimulation of the neuron causes a prion-like protein, CPEB (cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding protein), which is present in all ynapses, to become activated (to an infectious form), which in turn activates the dormant messenger RNA, which in turn makes protein to form a new synapse. The prion-like infectious form of CPEB infects adjacent CPEB, and thus perpetuates itself and the protein synthesis, maintaining and re-enforcing the new synaptic connection (Kandel, 2006). In higher organisms, the stimulus that reaches a neuron resulting in this series of events is itself modified in several interneurons which have their own connections, i.e., stimulus (perception) is modified by existing memory (memes). Furthermore, neurons are capable of generating impulses without external stimulus, which may stimulate and reinforce connected neural clusters (memes).

Originally, Dawkins pointed out that memes are replicated in the brains of those who imitate. As these replications are not always exact, memes undergo Darwinian natural selection and evolution as they are copied from brain to brain. How about the memes within the brain?

Edelman described Darwinian natural selection of certain clusters of reinforced neurons in the brain in somatic time (Edelman, 1987).

4. Cognition as Meme Processing

When a problem is perceived, that perception arouses interconnected memes which may be in some way related to or resembles it, be it temporal, sonic, visual, semantic, or symbolic way. Then, the problem is

Cognition is one of the brain’s activity of processing memes. This may involve comparing new memes with existing ones, juggling existing memes to make way for new memes, rearranging memes by combining or breaking down memes and reassembling them. The brain may also absorb and process memes without cognition, e.g., empathy arising through mirror neurons (Agnew, Bhakoo & Puri, 2007; Craighero, Metta, Sandini, et al, 2007; Gazzola, Aziz-Zadeh & Keysers, 2006; Rizzolatti & Craighero, 2004), dreams, etc. (Agnew, Bhakoo & Puri, 2007; Craighero, Metta, Sandini, et al, 2007; Gazzola, Aziz-Zadeh & Keysers, 2006; Rizzolatti & Craighero, 2004)

The brain, in my view, is more like the internet than a computer, with redundant storage and constantly changing connections and storage, in which memes are constantly created, propagated, combined, disintegrated, mutated, and evolved. Like the internet, there are many interconnected processing centers that execute these functions. Some of these functions may involve a threshold number of processing units and reach consciousness, others without reaching consciousness. Just like information on the Internet, some memes stay dormant and others become activated and replicated.

Reiser postulates that these impulses will readily activate neural circuits with relatively low excitatory thresholds, i.e., those circuits that retained memories of meaningful experiences to which emotions are attached and connected to current life problem (Reiser, 1990). These circuits would be those that represent significant memes stored during the day. During dreaming, then, the newly introduced memes may find new connections with already stored memes, and combine with some forming new memeplexes, and may awaken others from a dormant state, or may become dormant or be simply discarded.

In dreaming state, existing memes may find connections with newly introduced memes or with each other, becoming potentiated and reach consciousness. Thus, in dreams, we may have a glimpse of the memes struggling with each other, constantly making and breaking new alliances, configurations, and reproductions within our brain.

5. Environment affects Genes through Memes

It is widely accepted that genes play an important role in mental health and illness. As an example, a single gene that codes for the vulnerability to multiple psychiatric (and medical) conditions is the serotonin transporter gene (SERT) and its promoter region polymorphism (5-HTTLPR). SERT is highly evolutionarily conserved and regulates the entire serotoninergic system and its receptors via modulation of extracellular fluid serotonin concentrations. 5-HTTLPR polymorphism consists of short (s) and long (l) alleles, and the presence of the short allele tends to reduce the effectiveness and efficiency of SERT. The short allele has been identified as

Pezawas et al. (2005) showed that the short allele carriers show reduced gray matter in limbic regions critical for processing of negative emotion, particularly perigenual cingulate and amygdala. Functional MRI studies of fearful stimuli show a tightly coupled feedback circuit between the amygdala and the cingulate, implicated in the extinction of negative affect. Short allele carriers showed relative uncoupling of this circuit and the magnitude of coupling inversely predicted almost 30% of variation in temperamental anxiety. They also show increased amygdala activation to fearful stimuli (Bertolino et al., 2005; Hariri et al., 2002). Thus, this gene seems to increase the affected individual’s brain’s sensitivity to negative affect and anxiety (Gross and Hen, 2004). However, not all short allele carriers develop depression.

Caspi et al. (2002, 2003) have shown, in an elegant longitudinal study, that stress during the most recent 2 years in adulthood and maltreatment in childhood interacted with the 5-HTTLPR status. Individuals with two copies of the short allele who also had the stressors had greatest amount of depressive symptoms and suicidality than heterozygous individuals, and those with only the long alleles had the least amount of depression.

Studies in monkeys have shown that the anxiety-enhancing effect of the short allele is mitigated with good mothering in infancy (Barr et al., 2004; Suomi, 2003, 2005).

Thus, 5-HTTLPR short allele, in conjunction with childhood stress, confers an individual with the trait to respond to later stress with increased anxiety, which, in turn, predisposes the individual for later major depression, suicidality, and psychophysiologic disorders (Caspi, Hariri, Holmes, et al, 2010; Sugden, Arseneault, Harrington, et al, 2010; Uher, Caspi, Houts, et al, 2011). Other gene–environment interactions predisposing to trait and disorder have been reported, including type 4 dopamine receptor gene (D4DR) and novelty seeking and ADHD (Ebstein et al., 1997; Keltikangas-Jarvinen et al., 2003), monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) and antisocial personality (Caspi et al., 2002; Craig, 2005), and dopamine transporter gene (DAT1) and ADHD (Brookes et al., 2006). FKBP5 polymorphism (a glucocorticoid receptor-regulating gene) has also been shown to interact with childhood abuse in increasing the risk of PTSD in an urban general hospital population (Binder et al., 2008).

How does the environment and stress affect the genes exactly? The fact that a recent meta-analysis failed to show a significant interaction between the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and stress in the risk of depression (Risch et al., 2009) highlights that the interaction is not a simple gene × stress, but rather mediated by the individual

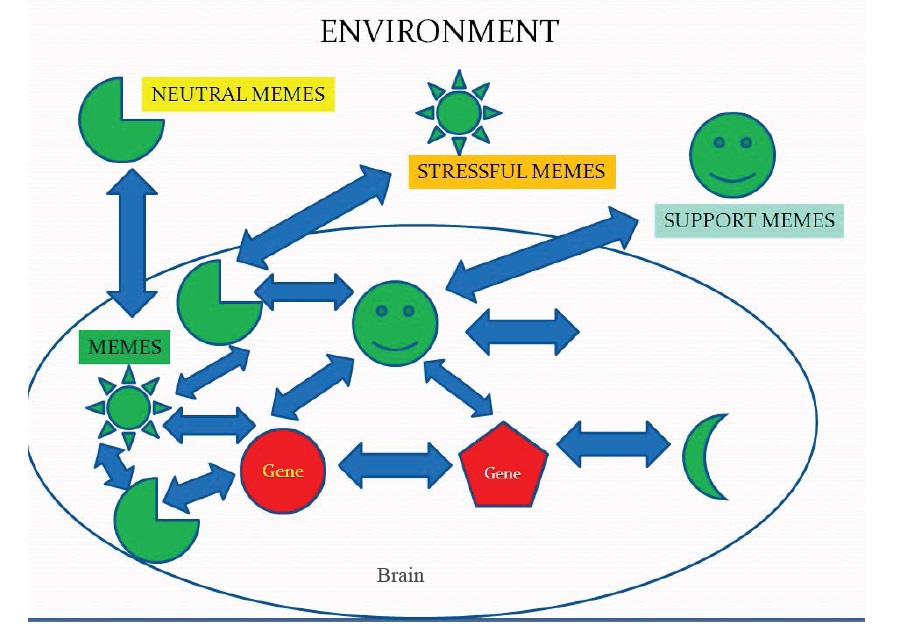

When a sensation from a sensory organ reaches the brain, it is processed against existing templates formed by both genetic predisposition and memory, the output of this process constitutes perception. The templates and the percept are memes. Environment affects and interacts with genes through memes in the course of development, and mental health and mental illness are the outcomes of this interaction. See Figure 1.

6. Infusion of Memes from the Environment

The environment consists of memes and potential memes like a culture medium in a Petri dish. The culture medium consists of molecules, some of them nutrients, some of them toxins, and others inert. Some enter the organism and become a part of it or give it energy. Others may simply enter and stay without much effect. Under certain conditions, such as an increase in the concentration of the toxic molecules, some such molecules will penetrate the protective barrier of the organism and cause a reaction in the host – perhaps an immune reaction that gets rid of the toxic molecule, or the organism may succumb to the toxin. The shape and nature of the toxic molecule play important roles in whether it enters the host, and what happens afterwards. So with memes. The shapes and other characteristics of the vehicles of memes are physical in nature

such as printed words, spoken words, melodies, rhythm, scenes, movements, facial expressions, touch, etc. (Of course, memetic vehicles are themselves memes, and some memes represent physical objects, either concretely or metaphorically, such as color blue, seeing red, etc.)

Memes contain various specific sensory components that can be identified and analyzed. For example, an unexpected good or bad news may be introduced into the brain in different memetic vehicles, e.g., as a phone call, a letter, a news item on TV, etc, which cause different patterns and sequence of brain activation and thus affective arousal. Thus, the sound of a phone call may reverberate (replicate) repeatedly in the brain while a visit by a friend bearing the news may be soon forgotten. Stress thus may be definable through an analysis of the types and quantities of memes and their vehicles that invade the brain.

Memes are above all replicators. The invader in the culture medium analogy is a replicating virus. The stress memes interact with resident stress memes in the brain, which will tend to cause a cascade of stress meme replication. Counterbalancing this tendency is the host immune response, the negative feedback loop to amygdala from the cortex that may be effective in shutting off the stress response – if the protective memes are prepared and abundant. Chronic stress diminishes the number of hippocampal neurons and causes an attenuation of the hippocampal dendritic connections resulting in a disconnection between long-term memory (resident memetic store that may attenuate the stress response) and current stress meme infusion, a favorable circumstance for invasion of new memes.

The arousal and activation associated with acute stress may create a condition for heightened receptivity for meme infusion from the outside, while the deleterious effects of chronic stress on the brain serve to protect the stress memes from resident protective memes. Dormant stress memes may also be activated by the incoming stress memes, especially as the protective memes are attenuated.

Recognizing that memes are independent replicators whose only concern is replication of themselves regardless of consequences to the host organism may explain why humans are so prone to meme invasion and stress response.

7. Pathogenic and Protective Cultural Memes

Culture, consisting of symbols –language, artifacts, rules, is a pool of memes. Memes enter the brain and take up residence in the brain. Endemic (cultural) memes introduced in childhood are strongly potentiated as they are repeatedly introduced during a period when the filtration system for meme introduction is immature. Eventually, early-introduced resident memes contribute to the formation and development of the filtration system which filters out new memes that may conflict with or contradict the preexisting potentiated memes.

Within the meme pool (culture) of most geographic areas, there are memes for being “crazy” or “insane” as well as memes for anxiety and dysphoria. This is no wonder as many memes started out as imitations. Imitating the crazy one is surely the best way to be crazy, and imitating the one recognized as not feeling well is a good way of communicating that you are not feeling well. In isolated cultures, certain unusual (for other cultures) memes denoting such states have evolved, such as koro, latah, and ataques de nervios.

New memes or ways of expressing an internal state do arise and may become fashionable, such as some cases of fibromyalgia, “burn-out,” and multiple chemical sensitivity (Eriksen and Ursin, 2004).

As we discussed above, sustained stress, by attenuating the connection to memory and thus dominant resident memes, provides the brain with favorable conditions for new meme infusion. Such unchecked infusion of new stress memes may interact with dormant pathogenic memes hidden in the brain, stimulating their replication. A contributing factor may be that chronic stress causes sensitization to bodily dysphoric sensations (Eriksen and Ursin, 2004), which may in turn stimulate the pathogenic memes.

An example of such pathogenic memes may be depressive memes. Memes such as “I am worthless,” “I am a bad person,” “Nobody loves me” exist in many individuals, but are not prominent (reinforced) in everyday life. Such memes are not uncommonly introduced in childhood by adults, peers, and by exposure to persons who are despised (empathy is a form of imitation, and thus leads to memes).

Conversely, protective memes such as “I am loved (by parents, friends, spouse),” “I am competent,” and “I am good” are introduced to varying degrees during a person’s development.

Some of these memes may have been repeatedly introduced and were attached to positive emotions becoming a dominant part of the personality, others may have been introduced repeatedly but consciously suppressed, becoming attached to negative emotions, and may have stayed in a dormant, repressed state within the brain. It is these repressed memes attached to unpleasant affect that chronic stress permits to multiply and reach consciousness.

8. Mental Health as Memetic Democracy

In the beginning, memes were obviously in the service of the genes - memes that elicited the pleasure experience were readily incorporated, and those that elicited the fear/punishment response were discarded. Memes that arose from individuals who were successful were welcomed as they promised pleasure. As memes became more numerous, and became free-floating in books and electronic media, largely independent of the brain from which they rose, the link between memes and immediate pleasure or fear became largely uncoupled.

Now in the form of information and knowledge, memes are to a large extent emotionally neutral, neither pleasure nor fear. Thus, memes became independent of genes, i.e., memes that were indifferent or even hostile to genetic biological needs could thrive, especially when encapsulated in memeplexes such as doctrines, religions, and other -isms.

Modern human brain is immersed in an ocean of memes of all shapes, colors, and sizes, mutually compatible, incompatible, or indifferent. The brain is a Hobbsean universe of memes where each meme is out for itself against all other memes. It is natural, then, that some memes should form alliances with each other, and recruit other allies to form small cooperating societies, or memeplexes and complexes of memeplexes. Thus, small societies of memeplexes develop, and there may be tension, cooperation, or frank conflict among these societies of memes.

From early childhood, memes that stand for social norms, codes of conduct, and ways of relating with people, enter the brain. Some social memes are created by the brain through trial and error, e.g., the child learns that it is more effective to ask with a smile rather than with a frown. Such autochthonous memes may be augmented by imitation of others, or may spread by others imitating them. The learning of morals and ethics may be through a combination of memes introduced from outside as well as trial and error. Some social memes, such as a tendency toward altruism, may arise from genes that have been evolutionarily selected sociobiologically (Wilson, 1980).

During adolescence, there is an influx of new memes as the developing brain has now gained the ability to abstract and to absorb abstract memes. There is confusion, conflict, and turmoil among the competing memes. Some already resident memes may be called to question by new incoming abstract memes. Eventually, one or more memes are identified as comprising the essence of the self, the

When the dominant selfplexes in different domains are in reasonable harmony with each other, they are called roles that can change smoothly depending on the setting. When a selfplex for a particular role asserts dominance over others, for example, a religion, then there is potential conflict. Such dominant selfplexes often recruit self-serving memeplexes such as prejudice against others and chauvinism. Counterbalancing such memes are tolerance memes and freedom memes.

How the selfplex and other societies of memes should relate with each other is a meme itself, and has a number of variations. One model is that of an authoritarian and tyrannical regime in which one selfplex ruthlessly suppresses others. The self is, therefore, seen to be unitary and coherent with a strong identity, with strong support by prejudice and chauvinism memes. Authoritarian selfplex is subject to violent overthrow by the repressed memes and memeplexes if they are energized by an infusion of new memes or if the selfplex is weakened either by a decrease in brain function, or by infusion of conflicting memes.

An example of the fear an authoritarian selfplex exhibits toward new meme infusion is censorship. Individuals with authoritarian selfplexes tend to advocate censorship, for example of “bad words.” Of course, the “bad words” are resident in the brains of those individuals as memes; otherwise they would not recognize a “bad word.” And they are often preoccupied with the “bad words” and they look for them in everything they see or read. This is an example of the replication of the resident memes represented by the “bad words,” and how the authoritarian selfplexes are threatened by it.

Another model of interaction of memes and selfplexes in the brain is that of an enlightened sovereign or of an oligarchy, where the selfplex maintains hegemony but is open to coexistence with other selfplexes and conflicting memes, and recognizes them as legitimate, some of them more so (the aristocrats, so to speak) than others.

Yet another model is a democracy of selfplexes where there is recognition that different senses and objectives of the self can coexist, and depending on the needs of the genes and the environment, the different selfplexes may be elected to be dominant, with the consent of the ruled (Benjamin et al., 1996; Cohen et al., 2005; Ebstein et al., 1996; Okuyama et al., 2000; Shiraishi et al., 2006; Van Gestel et al., 2002).

The memes within the selfplexes are not mutually exclusive, i.e. – some memes may participate in more than one selfplex. Just as an incoming administration in a democracy may retain some of the cabinet members of the outgoing administration of another party, newly dominant selfplexes often retain memes of a now nondominant selfplex. Furthermore, the memes that form the day to day working of the memetic government, like bureaucrats in a government, continue to function regardless of the changes in dominance of selfplexes. This model of memetic relationship in the brain may offer the most flexibility and least oppression. Unlike in multiple personality in which a repressed selfplex overturns the dominant one temporarily, in a democracy the change of regime is based on rational needs and is effectuated without suppression of the now nondominant selfplex.

In a memetic democracy, the selfplexes may be likened to major parties that recognize the right to exist of the minor, even subversive parties. Thus, revolutionary memes and subversive memes, and even toxic memes, can exist in a state of check and balance, and may express themselves in accepted forms such as creativity and art. Freedom, tolerance, and openness memes are universally accepted by the competing major selfplexes. The brain as a well-functioning memetic democracy may well fit the bill for a model of mental health taking into consideration the gene x meme x environment interaction.

The self is not a coherent and unitary entity, but an equilibrium of constantly changing selfplexes in a sea of memes. The self is a fragile, uneasy coalition of memes that is subject to changes of regime and revolutions. Mental health is a state of well-being of the gene–meme interaction in the brain. Such well-being is most likely achieved in a memetic democracy within the brain that recognizes both genetic and memetic needs, provides an orderly mechanism for their expression and mechanisms for adaptation to changing demands, and strives to maintain both cohesiveness and diversity within the societies of memes.

9. Mental Illness and Final Common Pathway Syndromes

Mental illness ranges from universal unhappiness arising from the human condition to serious distortions of reality in the form of delusions and hallucinations. Somewhere in between the two extremes is

Neurosis, often manifest by moderate anxiety and/or depression, is generally considered to be a result of developmental hang-ups and faulty learning (Sadock, 2005). Any number of developmental theories, Freudian, Jungian, Eriksonian, etc., can provide clues to the repeated traumas and failure or inadequacy in mastering the demands of the developmental stage resulting in residual unconscious conflicts and faulty patterns of expectations and behavior.

Developmental task can be conceptualized as the integration of newly introduced and newly arising memes with the needs of unfolding genes. Neurosis denotes a state of the brain where the mutually incompatible and conflicting memes and memes representing genetic needs have not found a workable modus vivendi, where workable democracy has not developed in the brain. There may be an authoritarian brain state where a large number of memes that are potentially salutary are in a state of severe suppression; or a state of near anarchy where competing memes and selfplexes achieve ephemeral dominance.

Repeated exposure to fear and violence memes in childhood, when the meme-processing faculties of the brain are not fully developed, may render the brain susceptible to replication of these traumatic memes and further stunt the growth of the executive function. When any attempt at exploration and initiative is met with violence and trauma, fear memes and violence memes will replicate. When a revolution overthrows an authoritarian memetic regime, anarchy often results as the dominant selfplex did not condone the coexistence of a viable alternative selfplex to take over in an orderly fashion as in a democracy. The anarchy of conflicting memes may generate overewhelming anxiety, which in turn may trigger a gene-driven cascade of physiologic arousal into a final common pathway psychiatric syndrome.

These syndromes are serious conditions reflecting a pathologic brain state that, without treatment, results in an autonomous course and often chronic outcome. Schizophrenia, major depression, manic-depressive bipolar syndromes, panic anxiety, and psychoses are the major examples of final common pathway syndromes. In all these syndromes, the meme-processing executive function of the brain is severely impaired, and thus general reduction in meme proliferation as well as directly gene-oriented therapy are necessary.

10. Gene and Meme Directed Therapies

The recognition of gene – meme interaction and the role of stress that arises at least in part from memetic conflicts in mental illness provide us with a new perspective in therapy. Psychiatric therapy should be geared toward both genes and memes.

This should take into account the epigenetics of the person, i.e., what physical and memetic stresses in early life caused which genes to be turned on or off resulting in the vulnerability to mental illness, and how can we reverse it? (Mehler, 2010; Tsankova, Renthal, Kumar, et al, 2007; Weaver, 2007; Weaver, Champagne, Brown, et al, 2005; Weaver, D’Alessio, Brown, et al, 2007; Wong, Caspi, Williams, et al) Gene oriented therapy is not limited to drug therapy. In fact, there is evidence that a nurturing environment in adulthood and psychotherapy may be effective in reversing the effects of early stress on specific genes and thus the micro- or macro-morphology and function of the brain (Mehler, 2010; Weaver, 2007)

The recognition that memes interact with genes, and that memes are actual functional neuronal units that may have various components such as thoughts, beliefs, sounds, imagery, colors, texture, and emotions opens up a whole new world of meme-oriented therapies.

A. Broad Spectrum Meme-Oriented Therapy

In treating infections by microorganisms, broad-spectrum antibiotics have been particularly useful as they target a broad range of organisms. Especially in the case of mixed infections, they can be particularly useful. Similarly, there are broad-spectrum therapies that may be geared to suppressing a broad range of memes. Of course, as in the case with antibiotics, broadspectrum memetic therapy may have the side effect of suppressing beneficial normal flora of memes as well. Nevertheless, when the unchecked multiplication of memes may be overwhelming, broad-spectrum anti-meme therapy can be a very effective method of controlling the situation and preventing an escalation of the memetic multiplication.

How can we actually achieve this? Antibiotics generally interfere with the replicative mechanism of the microbe. Memes replicate through signal reinforcement of the neural clusters that make up the memes and by recruiting other neural clusters through the development of new synaptic and dendritic connections. These old and new connections are enhanced by attention, affect, and thinking. Thus, depriving the pathogenic memes of attention, affect, and thought and thus the neural reinforcement would interfere with their multiplication.

An obvious approach is pharmacological intervention, a direct suppression of attention and cortical activity. It is well known that most mental illness is associated with insomnia and the promotion of sleep with drugs have beneficial effects (Wichniak A 2012). Many tranquilizers, especially benzodiazepines, induce drowsiness and reduced attention. Antipsychotic drugs and antidepressants are often chosen for the “side effect” of sedation as well as for the specific action. Many patients on these drugs also report a blunting of their affect.

There are a number of extant nonpharmacologic techniques that are considered to be valuable in promoting mental health, but the reason why they are effective has not been clearly defined. They include such diverse techniques as relaxation training, meditation, hypnosis, bath, massage, music therapy, dance therapy, exercise, and bibliotherapy. In the light of our understanding of memes, it is clear that all these techniques have in common the focusing of attention on something other than the thoughts and feelings that are distressful, and thus the ability to suppress the multiplication of memes.

B. Specific Meme-Oriented Therapy

Existing formal psychotherapies including counseling are essentially memetic, i.e., memes are transmitted back and forth between the patient and the therapist through the process of talking. Psychotherapies work through meme manipulation in the brain of the patient.

Psychotherapy and counseling have nonspecific and specific effects. The nonspecific

effects have to do with the supportive presence of another human being, the therapist, who is interested and committed in helping the patient. The specific effects have to do with the particular form of psychotherapy and its presumed theoretical mechanism for helping, e.g., cognitive reframing, insight, or corrective emotional experience. It is generally recognized that psychotherapy and counseling work, especially in conjunction with medications in more serious mental illness, but it is not entirely clear whether the nonspecific or specific effects are more important in the effectiveness of psychotherapy, as the effectiveness does not seem to depend on the form of psychotherapy (Bergin and Garfield, 1994;Consumer Reports, 1995).

Nonspecific aspects of psychotherapy do have specific memetic effects including (1) the therapist is ipso facto a role model, a model for imitation in thinking and behavior, a source of memes; (2) during the regular therapy session, the patient feels protected and supported, i.e., the meme pool to which the patient is exposed is benign and protective, and may neutralize the pathogenic memes in the brain; (3) rational and critical thinking is encouraged during the sessions that enhance the brain’s meme-processing abilities.

I believe memes can serve as a unifying concept of all psychotherapies and would lead to the development of new psychotherapeutic concepts and techniques. Currently, psychotherapeutic “schools” tend to be dogmatic about their particular theory and emphasis. Thus, the therapist is either a cognitive–behavioral therapist or a psychodynamic psychotherapist. Though emotions and behavior can be observed and explained in either terminology, there is no common value-neutral terminology. Memes can provide that terminology which bridges cognitive, behavioral, psychodynamic, and neurobiological phenomena. A general understanding of chemical phenomena became only possible with the discovery of the atoms and their components, the protons, electrons, and neutrons. Until then, there was nothing in common between hydrogen, lithium, and sodium. Now we know that having only one electron in the outer shell, these elements have in common certain chemical properties such as being unstable in their elementary forms.

All psychotherapies, to a varying degree, attempt to identify pathogenic memes, trace their origins, and neutralize them and build a salutary selfplex. Regardless of the brand, the nonspecific effect of providing a memetic source (identification figure) is an important ingredient of effectiveness.

Novel therapies may be developed utilizing direct meme infusion and meme neutralization. Virtual reality populated by specific memes may produce an environment in which a patient’s pathogenic memes may be neutralized and protective memes may be augmented. Use of avatars, representations of oneself in virtual reality, may be an excellent meme-directed therapy (Bailenson, Yee, Blascovich, et al., 2008).

Prevention plays an important role in the gene x meme x environment interaction model of mental health and illness. Early nurturance provides protective memetic environment for children, and tends to turn off vulnerability genes. Childhood abuse and adversity introduce pathogenic memes to young brains as well as turning on vulnerability genes. Education of children in meme filtering and meme processing abilities including critical thinking and coping skills training as well as in broad spectrum meme attenuation techniques such as relaxation, music, and exercise, are important preventive measures.