1. The standard approach to the role of semantics when assessing the quality of analogies

The structure-mapping theory (Gentner, 1983, 1989; Gentner & Markman, 1997, 2005) and the multiconstraint theory (Holyoak & Thagard, 1989; Hummel & Holyoak, 1997, 2003) have dominated the discussion and computational modeling of analogical reasoning. As their computational accounts of the mapping and evaluation stages of analogical reasoning are representative of the main proposals that have appeared since the 80s, we will take them as the main exemplars of what we will henceforth refer to as the

The structure-mapping theory postulates that knowledge is represented in propositional form, and distinguishes between: a)

Suppose that SME receives a BA stating that

If the system were confronted with two competing TAs for a given BA, it would prefer the TA for which the emerging identity arises at a lower level of abstraction. Returning to the above example, given that decomposition would not reveal identities between

The multiconstraint theory of Holyoak and colleagues (Holyoak & Thagard, 1989; Hummel & Holyoak, 1997) conceives mapping as determined by a conjunction of syntactic, semantic and pragmatic constraints (the structure-mapping theory has contended that pragmatic factors operate either before or after—but nor during—the mapping and inference generation stages; see Gentner, 1989; Gentner & Markman, 1997). LISA (Hummel & Holyoak, 1997, 2003), the current computational implementation of the multiconstraint theory, is a hybrid system that combines the semantic flexibility of connectionist architectures with the sensitivity to structure provided by symbolic models. The core of LISA’s architecture is a system for representing dynamic role-filler bindings in working memory (WM) and encoding these bindings in long-term memory (LTM). When a proposition unit (P) gets activated, it propagates top-down activation to subproposition units (SPs) representing bindings between each of the case roles of the proposition and its corresponding filler. During the lapse while each SP unit remains active, it transfers top-down activation to two independent structure units representing a case role and its filler. These two types of structures—which represent the lower level in the structural hierarchy—in turn, activate a collection of semantic units representing their meaning. As different SP units within a proposition inhibit each other and inhibit themselves to inactivity once activated, they become active in an alternating fashion. Therefore, when a proposition such as

In LISA, syntactic constraints are enforced by sets of excitatory and inhibitory links. Within an analog, units of different hierarchy are linked by symmetric excitatory connections, whereas units of the same level share symmetric inhibitory links. In this way, when a predicate and an object unit in the source respond to patterns of activation in WM, they activate SP and P units above them, all of which tend to inhibit other units of the same type, thus enforcing a one-to-one mapping constraint. Once a P unit in the target has activated a corresponding P unit in the source, parallel connectivity is enforced by top-down activation of the structure units below them. Mapping hypotheses in LISA are connection weights created to encode associations in LTM between structure units of the same type across different analogs. The system increments the positive weights of these connections as a result of their temporal co-activation. The one-to-one constraint is further enforced in LISA through an algorithm that responds to an increment in the weight of a mapping connection between two units by decreasing the weight of all other connections leading to such units. LISA can put in correspondence two similar but non-identical relations and objects. Consider once again matching

In sum, whereas the structure-mapping theory posits that only relations count when evaluating the quality of an analogy, the multiconstraint theory contends that both objects and relations contribute to quality evaluations— a position also shared by authors such as Keane, Hackett and Davenport (2001), and Larkey and Love (2003).

A few studies sought to investigate whether or not human reasoners take object matches into account during the evaluation of analogical relatedness. The most thorough-going investigation of how people judge the quality of analogies across different kinds of matches is the “Karla the Hawk” series conducted by Gentner et al. (1993). Upon receiving pairs of stories that maintained different kinds of commonalities (including analogies and literal similarities), participants were asked to rate each pair for similarity and for inferential soundness—an operationalization of the quality of an analogy that consists of assessing to what extent one story could be used to draw inferences about the other. Regarding similarity judgments, literal similarities were judged as slightly more similar than analogies, thus showing a small but significant contribution of object similarities to overall similarity. However, in contrast to similarity ratings, soundness ratings were not affected by object similarities.

A limitation of the above study concerns the extent to which judgments of analogical soundness really inform how people perceive the quality of an analogy. From our point of view, Gentner et al.’s (1993) instructions were ambiguous as to whether they asked about the straightforwardness with which inferences can be derived from the analogy (i.e., soundness), or the plausibility of these inferences within the target domain. We tend to agree with Gentner and Kurtz (2006) on the convenience of probing judgments of analogical quality with more direct questions such as “To what extent do you consider these situations analogous?” Gentner and Kurtz (2006, Experiments 1 and 2) asked participants to give timed answers to whether a BA (e.g.,

2. Shortcomings of the Dominant Theories in their Treatment of Semantics

Despite their differences in terms of architectures, mechanisms and postulated representations, the revised computational models of analogical evaluation will consider two situations to be more analogous as the similarity between corresponding elements (relations and eventually objects, depending on the model) increases. However, this treatment of semantics seems inappropriate in those particular cases where the interaction between the elements composing the analogs invites descriptions that severely depart from the meaning of any of these elements considered in isolation. Sticking to Gentner and Kurtz’s (2006) example of near verb substitutions, the “standard” meaning of the verbs

The tasks we have been employing to show the role of semantics on analogical thinking (i.e., one BA and two competing TAs) could also serve to illustrate how the computation of element similarities can lead current models to misjudge the quality of an analogy. Consider, for example, a BA stating that

Confronted with the above task, LISA would prefer the mapping between the BA and the TA1, in response to the higher degree of similarity between their corresponding relations (

Even though SME’s evaluation of analogical quality would only take into account semantic similarities between relations, it would still choose the TA1 as more analogous. In so doing, the program would need to apply, for example, the rerepresentation mechanism of semantic decomposition proposed by Yan, Forbus and Gentner (2003) described above. Applying decomposition to BA and TA1 could result in:

In this case an identical semantic element (

The programs we have been describing could be extended to generate a common descriptor for the BA and TA1 by means of retrieving and combining the superordinates of the matched propositional elements (e.g., yielding a description such as a

1Gentner and France (1988) carried a study in which participants paraphrased sentences that combined verbs and nouns with varying degrees of semantic strain (e.g., The lizard worshipped). An analysis of such paraphrases revealed that verbs alter their meaning more than nouns do (see also Kesten & Earles, 2004). In the case we are considering (and in the materials of our experiments) the noun does not activate a particular meaning of the verb that applies to it—nor does it promote an extended use of it (e.g., a metaphorical one)—but it activates a concept whose meaning is entirely different from the verb on which it originates. For instance, John put poison in Mary’s soup prompts the concept “murder attempt”, whose meaning does not include the concept ofputting as an informative component. 2In this example, the particular way of breaking down relations and objects into their semantic primitives could have been resolved in many other ways, favoring perhaps the alternative mapping. For example, had buy-for and write-for (instead of buy and write) been coded with semantics such as generous or thoughtful, then LISA would consider write-for as a more viable match for bought-for. However, in deciding how to encode the meaning of elements one must try to avoid committing 20/20 hindsight, that is, tailoring the initial coding of the concepts so as to favor any particular interpretation of the analogy. What is clear is that our encoding (be it more or less accurate) should result in evaluations of element similarities that reflect people’s judgments. When coding this particular example, we had in mind that participants of an independent group (see Experiment 1) had judged that buy is more similar to lend than to write.

We presented participants with a BA followed by two alternative TAs, with the instruction to indicate which of them they considered as more analogous to the BA. The TA1s maintained only element similarities with their respective BAs, thus allowing the extraction of a common descriptor by means of combining the superordinate concepts shared by the matched elements. In contrast, TA2s maintained only overall similarity with the BA, which means that the descriptor subsuming both analogs could not arise from the combination of common superordinates. Within each set, both TAs were formally identical to the BA, that is, a one-to-one mapping satisfying parallel connectivity could be built between each of them and the BA. As was analyzed, in a task with this structure, SME and LISA would choose TA1s as more analogous to the BAs, based on the higher degrees of element similarity maintained by their matched relations and objects. Our goal was to determine whether participants would also prefer to match the BA to TAs maintaining this type of similarity, or if they instead preferred pairing the BAs with TAs maintaining overall similarities.

3.1.1. Participants

Thirty undergraduate students of Psychology at University of Buenos Aires took part in the experiment in partial fulfillment of a course requirement.

3.1.2. Design and Procedure

The independent variable was the degree of element similarity between base and target (high vs. low), a within-subjects variable. The dependent variable was the chosen TA. Materials were presented in written form and participants were tested individually. For each of the trials, participants had to read a first analog (the base one), consisting of a sentence that described a simple fact. Afterwards, they were presented with two other facts (the target ones), and they were asked “Which of these two facts do you find more analogous to the first?”

3.1.2. Materials

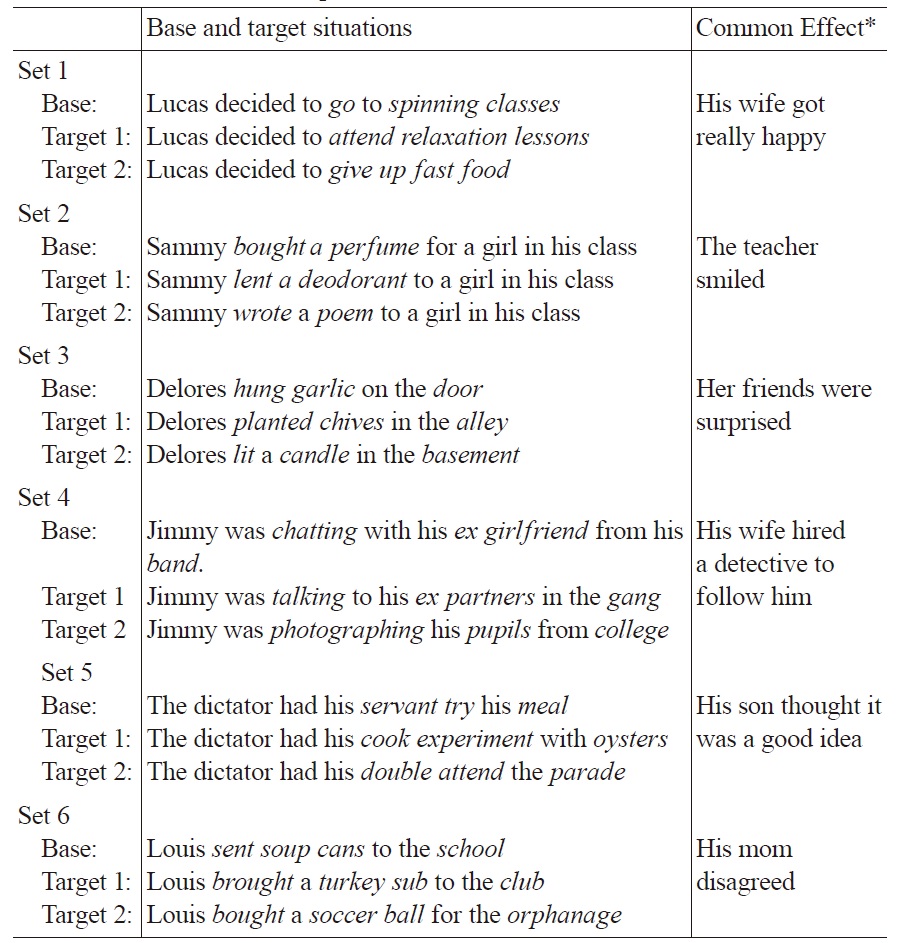

The TA1s were built replacing one or two verbs and one or two nouns in the BAs by verbs and nouns with very similar meaning. For example, in Set 6 of our materials (see Table 1), the BA was

[Table 1.] Materials used in Experiments 1 and 2

Materials used in Experiments 1 and 2

Participants received six critical trials and six fillers. To prevent participants from inducing an association between the presence of element similarities and the absence of overall similarity, the filler sets were built such that the TAs either shared both overall and element similarity with the BA or neither of them. For instance, for a BA like The

To gather independent measures of the degree of similarity between propositional elements to be mapped, we asked an independent group of 30 students (taken from the same population) to rate the similarity between the BA elements (e.g.,

In order to compare participants’ behavior in the experimental group against SME’s assumptions (this program takes into account only the similarity between matched relations at evaluating the quality of an analogy), the first analysis of the scores provided by the similarity-rating independent group was carried out comparing the semantic similarity between the base relation and the TA1 relation against the similarity between the base relation and the TA2 relation. For each set of materials, Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Tests confirmed that the relation in the BA was rated as more similar to that in the TA1 than to that in the TA2, with median [quartiles] ratings of similarity to base relations being 4 [4 4] vs. 1 [1 2],

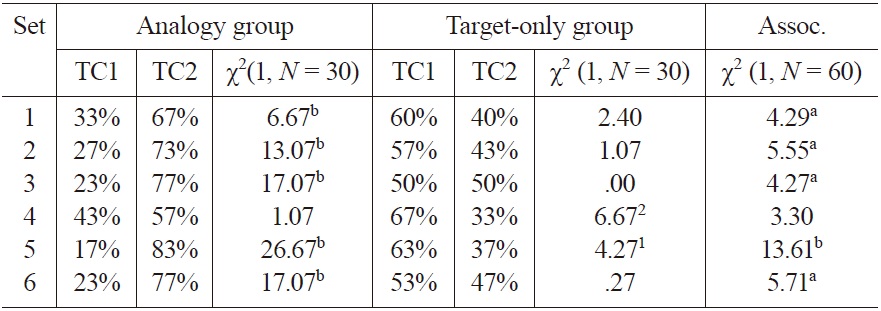

Table 2 shows the percentages of participants that chose, for each of the critical trials, TA1 or TA2. Data show that even though propositional elements of the BA were rated as more similar to their corresponding elements in the TA1 by the independent group, participants of the experimental group chose the TA2 as more analogous to the BA in five of the six critical sets (we found no trend in the remaining set). In sharp contrast with LISA or SME, participants’ assessments of the quality of analogies seemed to pass over element similarities, favoring more meaningful descriptors than those that can be generated by means of combining the common superordinates of the matched elements.

[Table 2.] Target choices, Experiment 1

Target choices, Experiment 1

As in several works studying the evaluation of the quality of analogies (e.g., Bassok & Medin, 1997; Gentner & Kurtz, 2006), our stimuli consisted in first-order propositions. However, the concept of analogy refers,

3In spite of the fact that the empirical studies reviewed (Gentner et al., 1993; Gentner & Kurtz, 2006) tended to show that only relations, and not objects, are relevant to the task of evaluating the quality of an analogy, we have remained open to the possibility that the latter have a role as well, as asserted by the multiconstraint theory (Holyoak & Thagard, 1989).

A central function of analogical reasoning consists of identifying the causes of target situations. Consider, for example, the case of a reasoner who has to choose among competing explanations for why a European country was led to bankruptcy. If the reasoner is familiar with a similar crisis undergone by another European country (and whose cause is known), he or she can identify a plausible cause for the target situation via deciding which of the target candidate causes is more analogous to the cause that gave rise to the familiar situation. In a similar way, participants of Experiment 2 were presented with a BA consisting of a base cause (BC) and its effect. They were told that the base effect later reoccurred as a consequence of a cause

In this way, the task used in Experiment 1—judging which of two TAs was more analogous to a BA—shifted to one of deciding which of two facts (both candidate arguments of a second-order causal relation) was more analogous to the BC. For each of our sets of materials, participants in a control group received the TCs but not the BA, and were asked to guess which of the two TCs could have generated the target effect. If target-only participants were less inclined than participants in the analogy condition to choose the TC that maintained overall similarity with the BC, then preferences among experimental participants should be attributed to the influence of the BA, and not to a higher intrinsic plausibility of TC2 as a cause for the target effect. We were interested in determining if, contrary to the criteria embedded in programs like SME or LISA, participants of the analogy condition would be more prone than participants in the target-only condition to choose TC2 as the more likely cause of the target event.

4.1.1. Participants

Sixty students of Psychology at University of Buenos Aires took part in the experiment in partial fulfillment of a course requirement.

4.1.2. Design and Procedure

The independent variables were element similarity between the BC and the TCs (high vs. low), a within-subjects variable, and condition (analogy vs. target-only), a between-groups variable. The dependent variable was the chosen TC. Materials were presented in written form. Participants were tested individually. After reading each BC followed by the action it provoked (i.e., the effect), participants in the analogy group were told that this last action reoccurred some time later as a consequence of an analogous cause. After that, participants in the analogy condition were asked to choose the more likely explanation for such reoccurrence: “Assuming that what caused this second event was

4.1.3. Materials

Participants were presented with six critical trials and six filler trials, which were identical to those of Experiment 1, except for the fact that the BCs— which corresponded to the BAs of Experiment 1—were now followed by an effect (see Table 1). Keeping with the critical set provided as an example in Experiment 1, the BA stated that

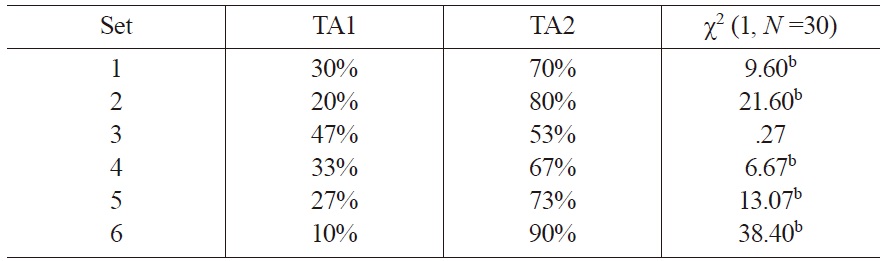

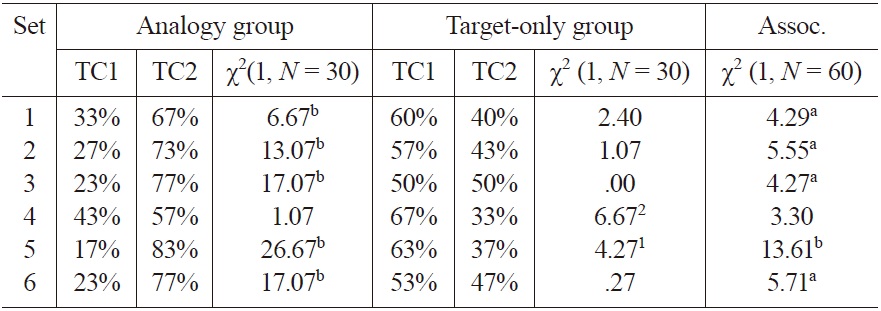

Table 3 shows the percentages of participants that chose TC1 and TC2 for the analogy and target-only groups, together with their Chi square statistics.

[Table 3.] Target choices in the analogy group and the target-only group, Experiment 2

Target choices in the analogy group and the target-only group, Experiment 2

Participants in the analogy group preferred TC2 to TC1 in five of our sets of materials, with no trend in the remaining set. Participants’ choices thus departed from those that SME and LISA would favor. The preference for TC2 in the analogy group cannot be attributed to a higher intrinsic plausibility of TC2s as the causes of the target effects, since the target-only group showed a preference for the TC1s or no preference at all, yielding an association between TC choice and condition in five of the six sets of materials (see Table 3). Data thus replicate results obtained in Experiment 1, but this time using more typical analogies (i.e., tasks demanding the comparison of systems of relations), and a more ecologically valid task (i.e., identifying the cause of a given outcome).

A crucial component of analogical reasoning consists of assessing to what extent two situations should be considered analogous. The present study set forth to determine if the semantic assumptions postulated by the structure mapping theory (as implemented in SME; Falkenhainer et al., 1989; Forbus et al., 1994) and the multiconstraint theory (as implemented in LISA, Hummel & Holyoak, 1997, 2003), are adequate to account for how humans judge the quality of an analogy. Despite a number of differences maintained by these theories in other respects, they share the idea that, all other things being equal, two situations will be regarded as more analogous whenever the elements that conform one of the situations are similar to the corresponding elements in the other, as determined by the mapping process.

As was thoroughly analyzed, if confronted with a BA stating that

We contended that an important limitation of the standard approach to semantics arises when it has to explain the assessment of the quality of analogies in which the interrelation between propositional elements in each analog invites interpretations and comparisons that go beyond the schema that would arise via assembling the superordinates of the paired elements. For instance, the sentence

The failure of programs such as SME or LISA to reject comparisons which (as we conjectured) people would readily consider as non-analogous is only one half of the story. By the same token, the above programs would fail to capture what we have called overall similarity–a type of analogical relatedness that comes out of comparing the meaning of whole propositions, and that cannot be derived from similarities between paired propositional elements. Programs would fail to acknowledge, for instance, the similarity between

Experiment 1 demonstrated that when deciding which of two TAs was more analogous to a BA, people pass over element similarities and seem to follow descriptors that cannot be derived from this type of similarities. Experiment 2 replicated these results embedding the first-order propositions of Experiment 1 within systems of relations, and replacing the task of evaluating the quality of an analogy between two simple facts with a more natural task that consisted of identifying the most likely cause of a target situation. Unlike SME and LISA, which would be biased towards element similarities, our participants proved to follow overall similarities.

Even though our results are silent as to the exact mechanisms underlying participants’ sensibility to overall similarities during the evaluation of analogies, we will share some intuitions about their nature. It seems likely that participants respond to the task of assessing the quality of an analogy by trying to assign the facts being compared to a schema-governed category of the type postulated by authors like Markman and Stilwell (2000; see also Goldwater, Markman & Stilwell, 2011). Instead of sharing a set of probabilistic features and feature correlations, members of schemagoverned categories such as

If people were to decide whether these situations are analogous via searching for superordinates for the pairs

In cases like these, people are likely to categorize the BA as an exemplar of superstitious behavior (since it is a typical example of that schema-governed category), and then evaluate if the TA could be considered an instance of such category. This kind of recategorization is likely to occur for schemagoverned categories, since the exemplars of these categories usually receive many and diverse categorizations (some of them not mutually exclusive), as compared to exemplars of entity categories (Gentner & Kurtz, 2005) (e.g.,

Finally, it could eventually happen that neither of the analogs is a typical case of a common schema-governed category:

In cases like these, as none of the analogs naturally elicits the superstitious behavior category on its own, it seems sensible to conjecture that the description of both analogs as instances of such category would result from searching for a schema-governed category capable of encompassing both situations, despite not being likely to be activated by either analog on its own.

On occasions, the schema-governed category finally applied to the base and target facts may not consist of a stable and lexicalized concept within the cognitive system, as evidenced by the difficulty implied in conceptualizing and verbalizing the reasons for accepting a given comparison as analogical. Consider, for example, the following analogs:

While it seems easy to consider the BA a case of superstitious behavior and the TA as an instance of religious practice, it is not easy to say which is the shared schema-governed category (one way of describing it could be “two supernatural modes of preventing the occurrence of a non-desirable sport outcome”).

A possible response to our critique of the standard model’s account of how analogies are evaluated could argue that the analogical machinery was not meant to deal with the activity of comprehending the analogs, but rather to start operating once each of the analogs has been fully comprehended. In this vein, the categorization of situations like

To the best of our understanding, the above objection faces a serious problem. A quick glimpse at our stimuli shows that, in contrast to this last example, in most sets at least one of the analogs cannot be considered a typical exemplar of the schema-governed category that is required to understand the analogy. For the objection to hold in these cases, the analogist would need to have represented the atypical analog as a member of a shared schema-governed category

Given that the rerepresentational mechanisms incorporated by the standard models of analogical reasoning basically consist of finding the least common superordinate concepts of the to-be-paired elements, it seems obvious than none of these mechanisms can give rise to a meaningful description encompassing both analogs. Furthermore, since the above interpretations of the BA and the TA are not formally equivalent, such mechanisms could not even be applied. That said, the recategorization of the TA as a case of

Regardless of the exact type of representations taken as input by the analogical engine, the question remains as to whether representing the analogs as instances of a shared schema-governed category is sufficient for evaluating the quality of analogies. It could be the case that beyond assigning the analogs to a common category, people still retain a rather concrete and specific representation of each of the analogs, which can be quite useful in determining to what extent two analogous situations should be considered equivalent. Upon completing the experimental session of Experiment 1, we asked several participants to justify why they had chosen TA2 as a better match to the BA. Participants frequently evoked schema-governed categories quite similar to those we had in mind when constructing our materials, thus providing anecdotal support for our intuitions about the mechanisms involved in judging the quality of an analogical comparison. More interestingly, we found that despite having chosen TA2 as more analogous than TA1, participants were far from considering TA2 as perfectly analogous to the BA. For example, after comparing

Even though our intuitions about the mechanisms underlying how people evaluate the quality of analogies surely await a great deal of theoretical refinement and empirical testing, we believe that they open up interesting perspectives for the development of theoretical and computational models of analogical mapping and evaluation. An important start could consist in incorporating schema-governed categories to the knowledge base of the programs, and taking hand of this information when convenient. However, in those cases where the shared schema-governed categories need to be constructed on the fly, the systems will need to handle large amounts of world knowledge in a creative way, a challenge that doesn´t seem to be attainable in the short run.