It is by now a well-established fact in Korean

However, despite the relative abundance of early Chosŏn texts with both

In his excellent description of the Asami collection, Fang (1969) describes this edition as follows: “28.40

What is most interesting about this work (and Fang’s description of it) for our purposes here is the fact that it contains numerous

My initial excitement about this text owed to two reasons: its status as a late-Koryŏ edition (of which there are precious few in North American collections), and the verbal morphology reflected in the annotations. At first blush, the latter appear to have been added in the late fifteenth (or perhaps early sixteenth?) century; if so, this would make them the oldest

In general, Kim Namgyun (2000) provides a useful point of comparison for a more detailed examination of the Asami edition’s

In addition to three officially designated ‘treasures’ also noted by Chŏng Chaeyŏng (2007)―Pomul 974, 1127 and 919 (the latter bound together with the

1This work was supported by the Academy of Korean Studies Grant funded by the Korean Government (MEST) (AKS-2011-AAA-2103). My thanks also to Professors Nam Punghyon, Jung Jaeyoung, Gernot Wieland, and John Whitman for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper presented at the “Workshop on Korean Historical Linguistics, with a Special Focus on Kugyŏl Materials,” hosted at the University of British Columbia, July 21-23, 2010. I am also grateful to two anonymous peer reviewers for their comments and corrections. 2Because the term ‘han’gŭl’ for the vernacular Korean script was not coined until the 19teens and did not gain wide acceptance until the 1930s, it is—technically speaking—anachronistic to use this term to refer to the Hunmin chŏng’ŭm 訓民正音 (or Ŏnmun 諺文) before the modern period, but in this paper I follow standard South Korean (anachronistic) practice for the sake of convenience. 3As of April 9, 2013, the entire text is available online for viewing and PDF download at the Internet Archive at this URL: http://archive.org/details/chonnokumganggyo008800rich. 4See also Chŏn (2006) for an annotated translation into Korean of this work and the more recent Yŏngnam Taehakkyo Minjok Munhwa Yŏn’guso (eds.)(2012) for a reproduction and transcription of the mid-13th century edition held at Yŏngnam University along with an overview of relevant research. (This Yŏngnam University edition does not have any kugyŏl glosses.) 5Henceforth, all pre-modern Korean linguistic forms are rendered in Yale romanization as per Martin (1992). Other Korean forms (proper names and technical terms) are rendered in McCune-Reischauer romanization. Transcription conventions for the glossed text are as follows: Chinese text from the Diamond Sūtra is in bold, while text from the Ch’ŏllo commentary is in plain. Righthand glosses are in subscript, while lefthand glosses are in superscript. 6The officially designated treasures are: Pomul no. 974 owned by the Seoul Museum of History (Sŏul Yŏksa Pangmulgwan); Pomul no. 919 (bound together with the Pŏmmang kyŏng 梵網經) owned by the Adan Mungo; and Pomul no. 1127 owned by the National Library of Korea. However, this latter copy appears to be unglossed. We can also mention: an early nineteenthth-century edition owned by Tongguk University; an edition from 1869 owned by Koryŏ University and the National Library of Korea; the Toyo Bunko copy; the Tenri Library copy from the Imanishi collection (glossed, but most of the glosses have been obliterated by a later reader); a nineteenth-century edition with glosses owned by Waseda University Library; etc. Chŏng Chaeyŏng and Kim Sŏngju (2010) report a late Koryŏ~early Chosŏn glossed fragment found recently at Pulgapsa Temple.

1. THE KUGY?L GRAPHS IN THE ASAMI EDITION CH’?LLO K?MGANG KY?NG

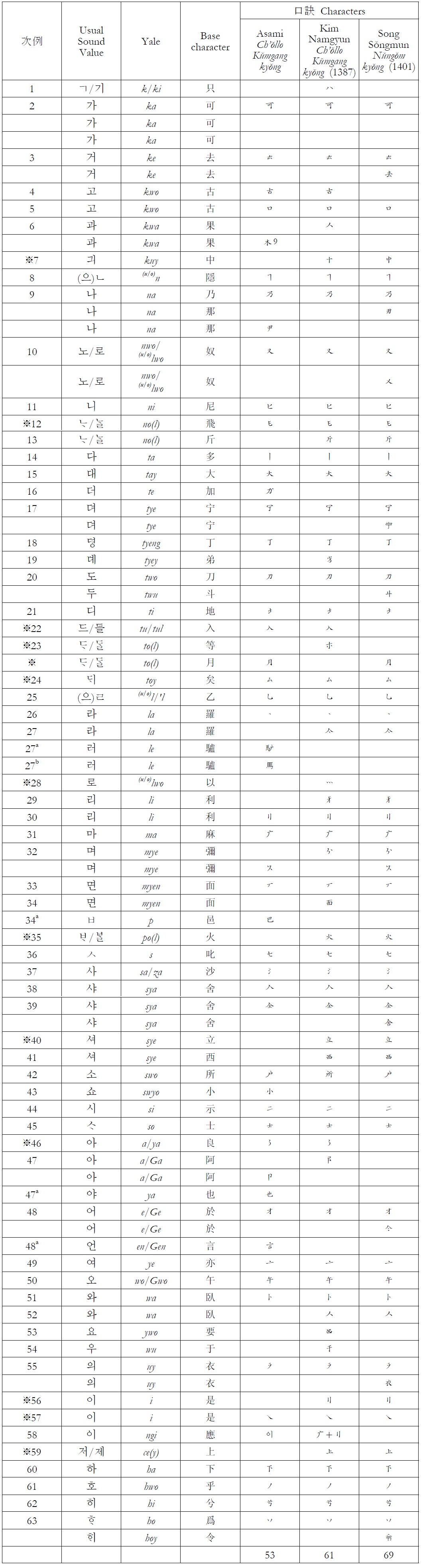

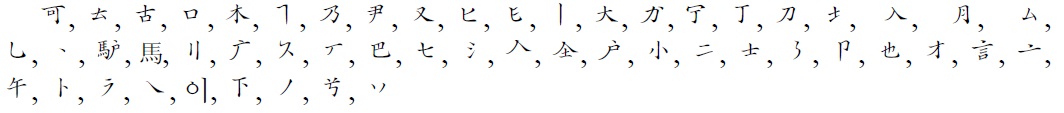

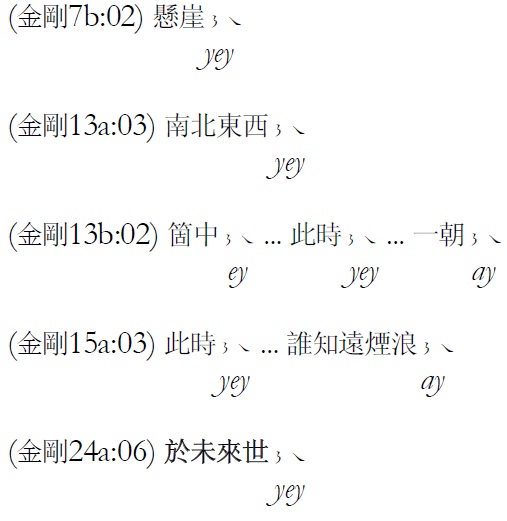

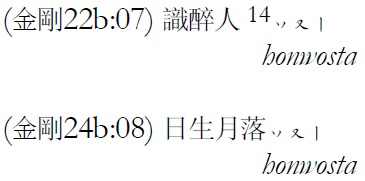

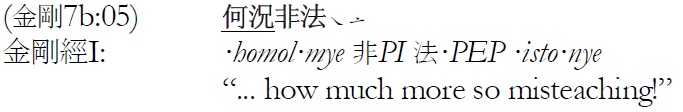

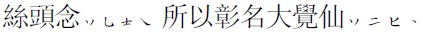

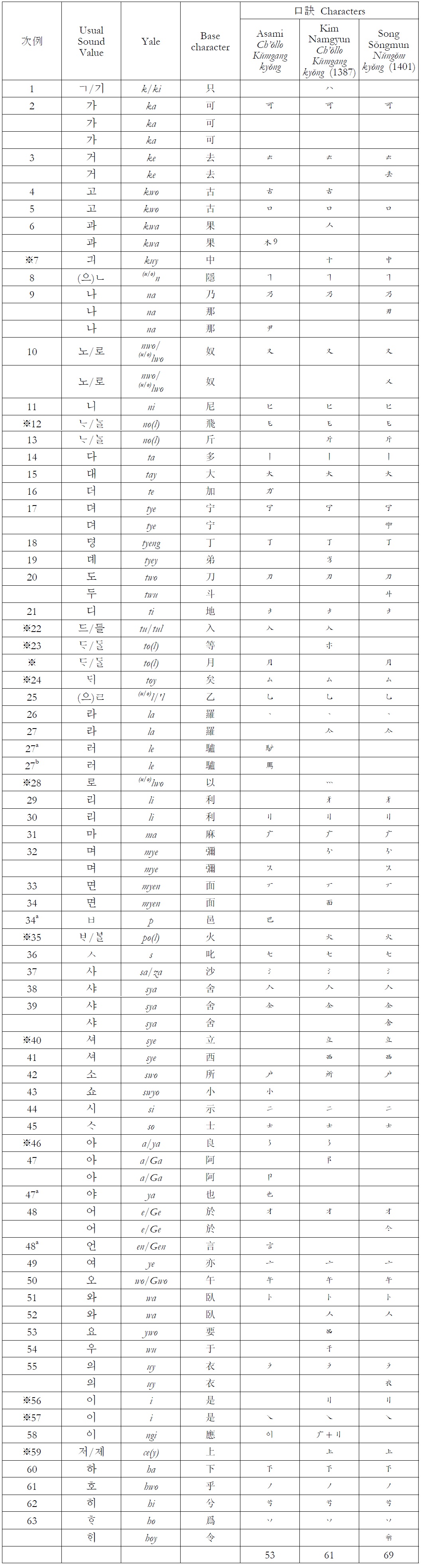

Please refer to the chart below for a full listing of the

[] The kugy?l Graphs in the Ch’?llo K?mgang ky?ng8

The kugy?l Graphs in the Ch’?llo K?mgang ky?ng8

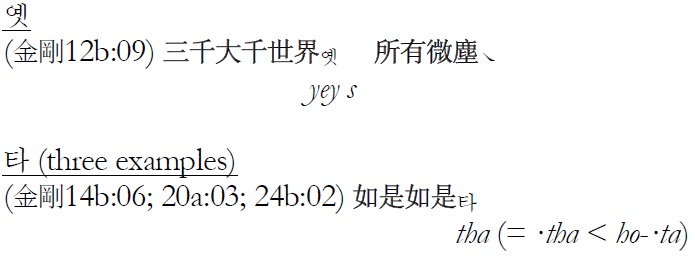

Including the

This is already a significant decrease in the total number of such graphs deployed in Koryŏ-era

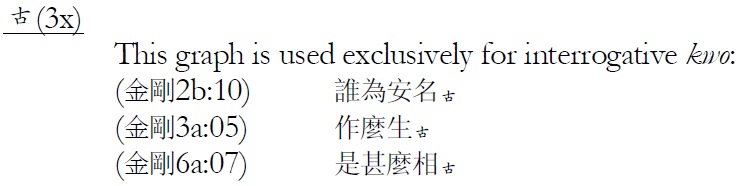

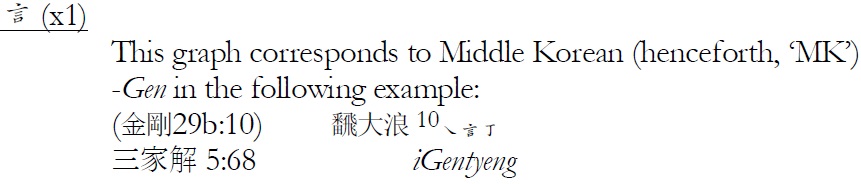

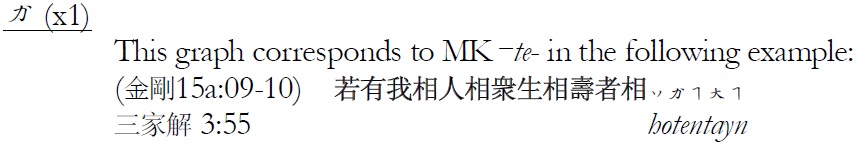

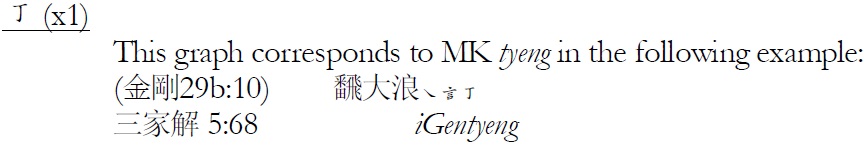

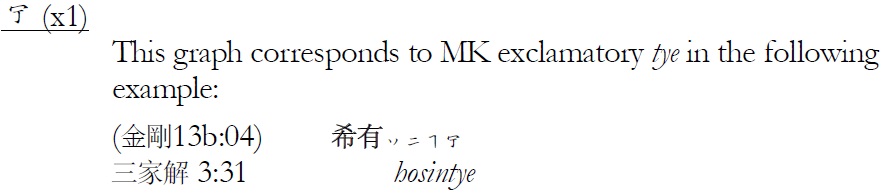

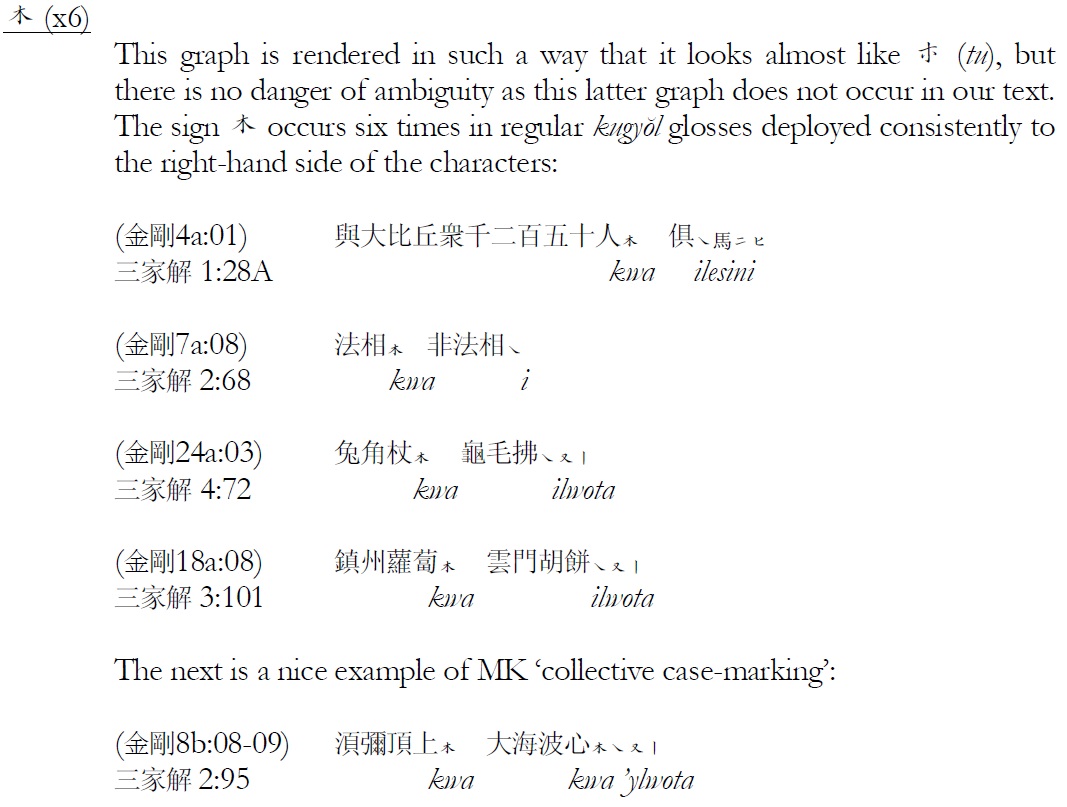

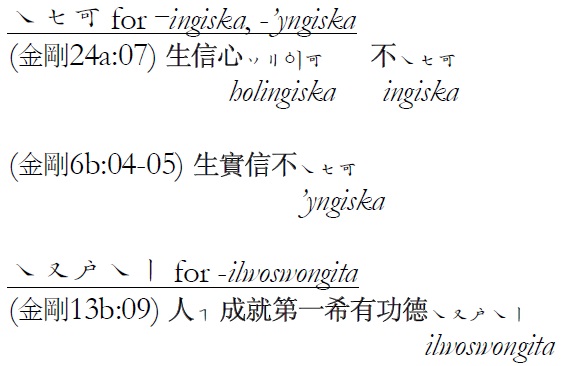

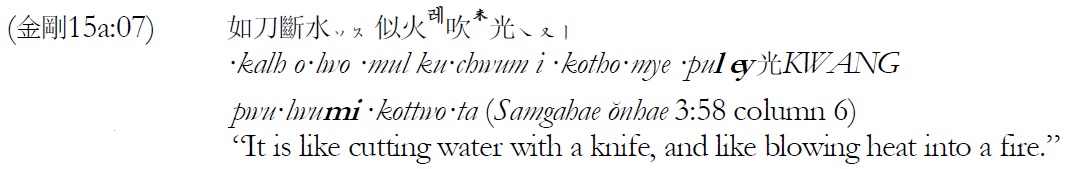

The following

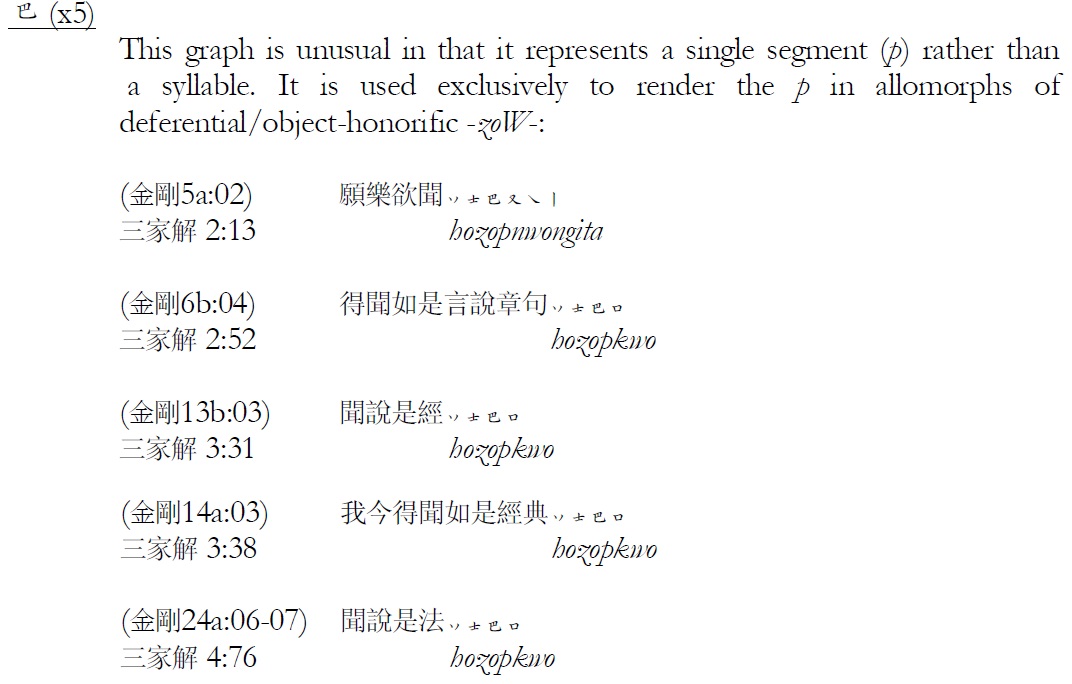

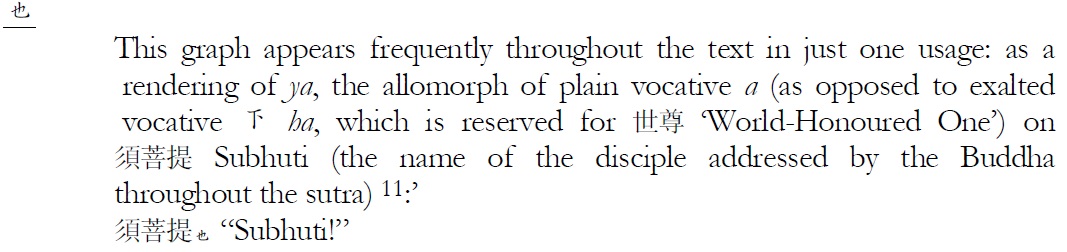

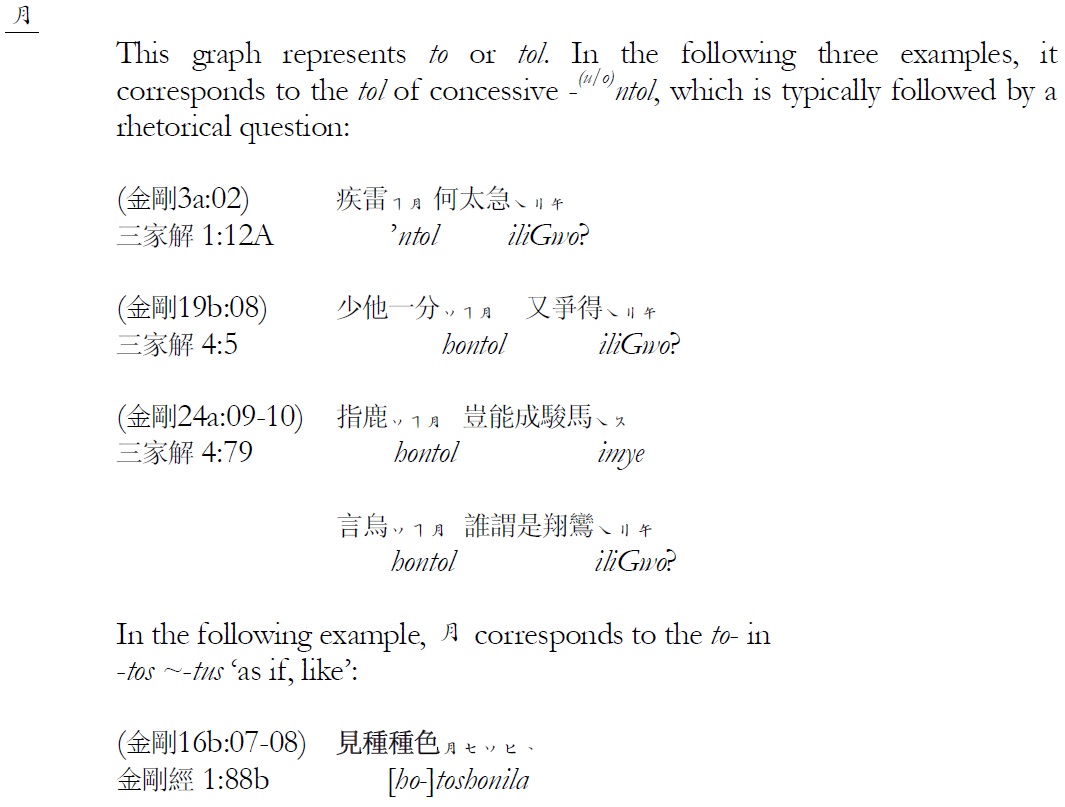

7As opposed to the Koryŏ-era sŏktok (釋讀 ‘interpretive reading’) kugyŏl that essentially translated the hanmun text into vernacular Korean with Korean word order. 8The chart is adapted from that in Kim Namgyun (2000:93-95), but also draws on Nam Kyŏngnan (2009). 9Note that is often rendered in such a way that it is difficult to distinguish from (tu). 10Henceforth, unless otherwise noted, all forms in italicized Yale romanization placed beneath kugyŏl markers represent the corresponding Middle Korean han’gŭl forms in the Samgahae 三家解. 11But note that there are also two examples of in this same vocative usage: (金剛 4b:09) and (金剛 5a:09). In both cases, the 1482 Samgahae ŏnhae records ya.

2. THE KUGY?L T’O(吐) IN THE ASAMI EDITION CH’?LLO K?MGANG KY?NG

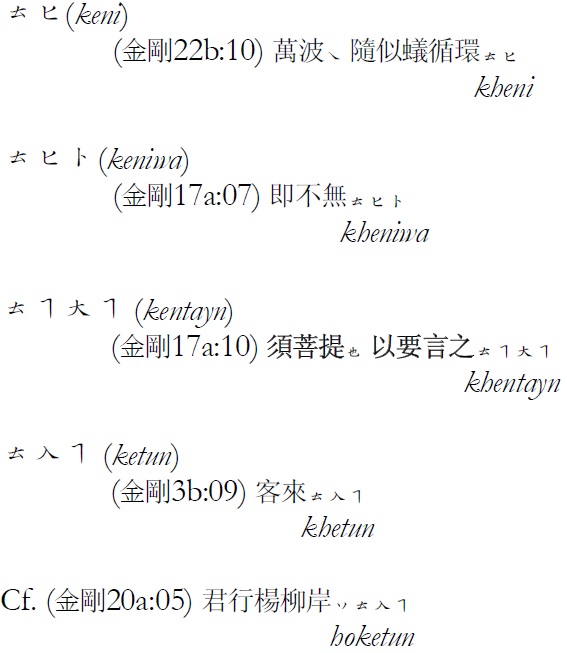

The Asami edition of the

The locative markers deployed in the

The

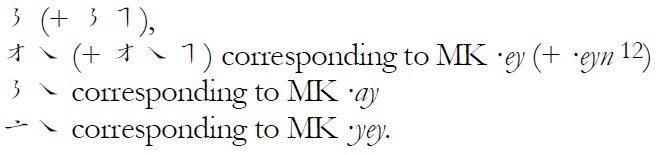

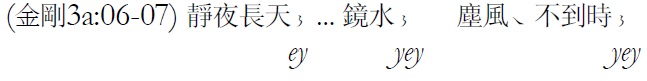

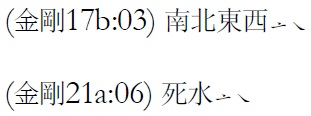

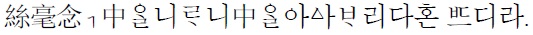

2.1.1. Examples of corresponding to Samgahae ey, ay, yey

1) 에

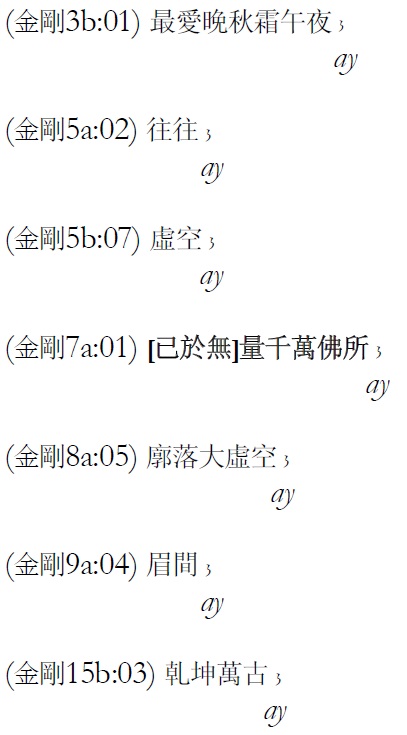

2) 애

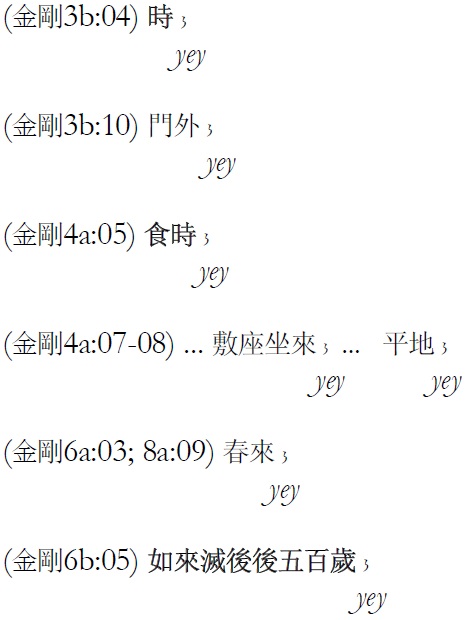

3) 예

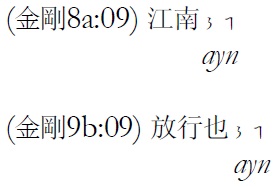

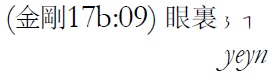

2.1.2. Examples of corresponding to Samgahae ayn

2.1.3. Examples of (ay) corresponding to Samgahae yey

Examples of corresponding to

In contrast with these five examples of corresponding to

Note that there is also one example of corresponding to

2.1.4. (ey) corresponding to Samgahae ey, yey

There are more than one hundred examples of =

Needless to say, these two examples should be treated as mistakes for on the part of the glossator.

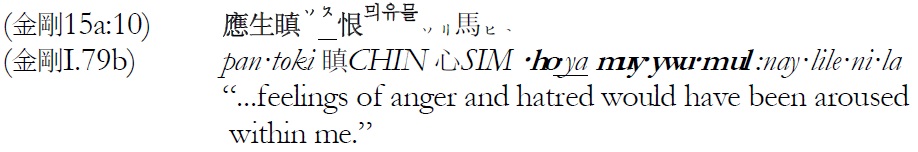

2.2. Ho-deletion vs. Aspiration

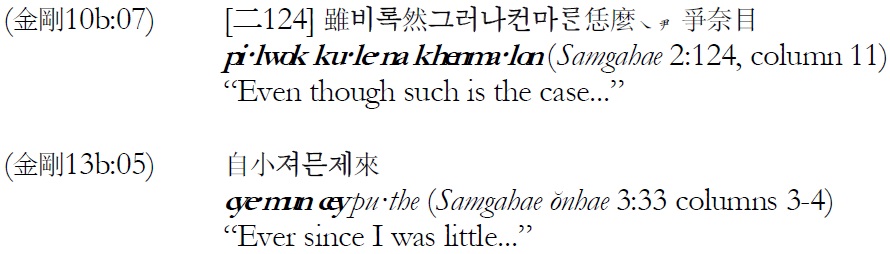

It is not uncommon in glossed texts of all periods for the stems

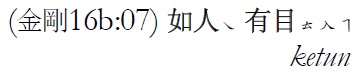

It is tempting to interpret examples like the following as somehow reflecting an archaic holdover of an interpretive glossing practice whereby 有 was read in vernacular Korean ([

A similar deletion phenomenon can be observed with =

But one also finds examples of just :

We also find cases of optional deletion of

2.3. Optional deletion of - s - ?

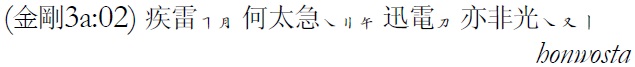

Our text offers nine examples of what Martin (1992:736) calls the modulated processive emotive indicative assertive in

However, there are also two examples where the same

It is tempting to interpret these examples as cases of optional deletion of -s- in this ending, but the following lone example of

The

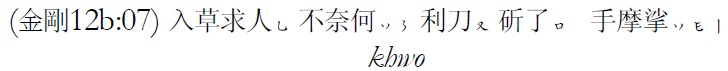

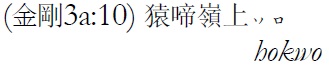

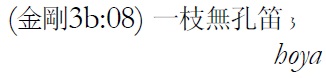

12There is just one example of 13One of the anonymous reviewers of this article made the interesting observation that ho-deletion is in fact rather infrequent in kugyŏl texts compared to copular i-deletion, and therefore questioned whether the examples in this section should be taken as instances of ho-deletion. To be sure, in some cases like these it is entirely possible that the deleted verb stem is the copula rather than ho-. However, the presence of parallel kugyŏl forms with ho- in the text along with the fact that the glossator was often copying from Samgahae han’gŭl glosses that clearly included ho- make this a rather vexed question. Note also that examples like 金剛 3b:08 一枝無孔笛 with just (and where the Samgahae shows hoya in any case) cannot be taken as instances of copular deletion, since there was no such combination as * (copula + -a). A comparison with other glossed versions of the Ch’ŏllo Kŭmgang kyŏng will likely clarify this issue somewhat, but note also that Nam Kyŏngnan (2009:89) records frequent examples of deletion of ho- before -ke-, and indeed, claims that deletion was the default practice. She also writes in footnote 29 on the same page that the materials she studied frequently delete ho- before . 14NB: The ŏnhae has 惜醉人 instead of 識醉人. 15However, the ŏnhae translation in the Samgahae renders our second example here as y·za.

3. INFLUENCE OF THE K?MGANG KY?NG SAMGAHAE 金剛經三家解

By now it should be clear that the

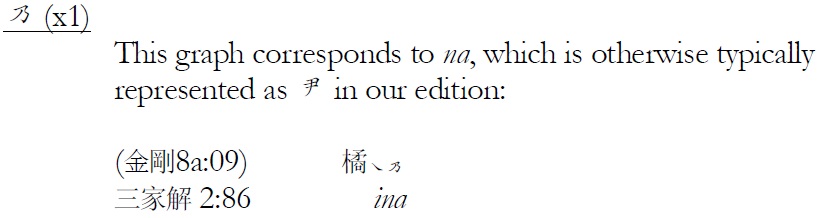

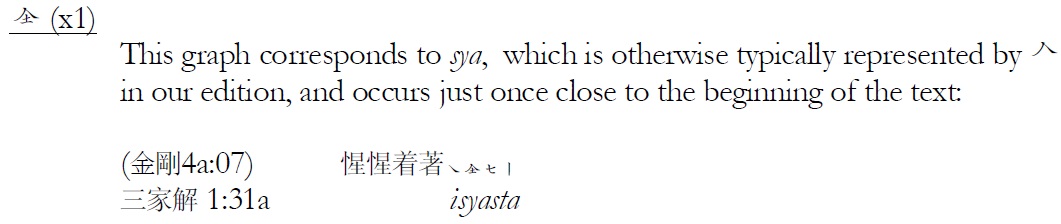

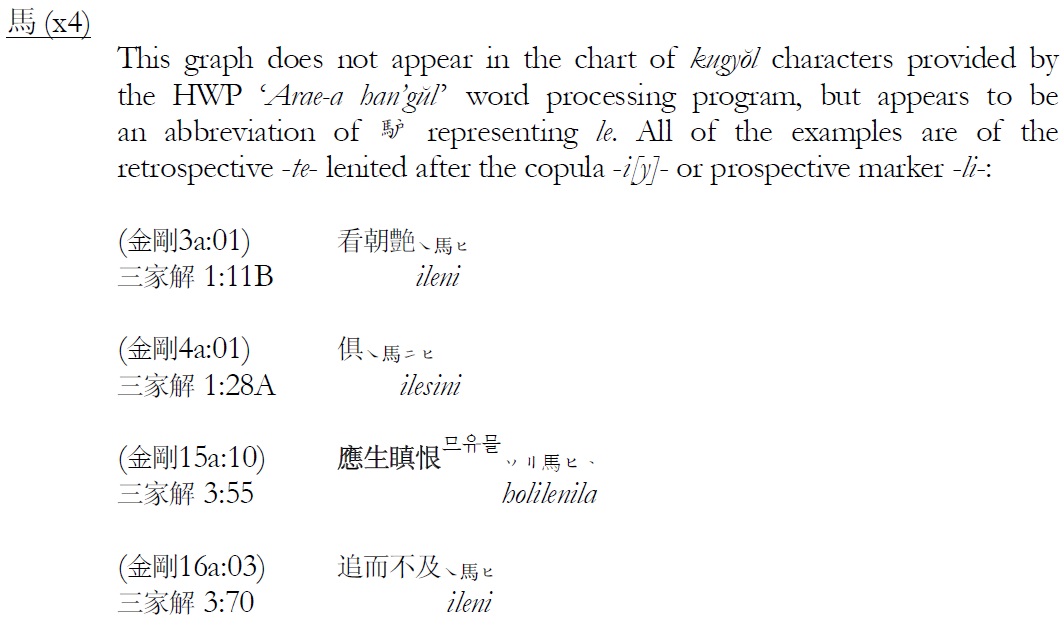

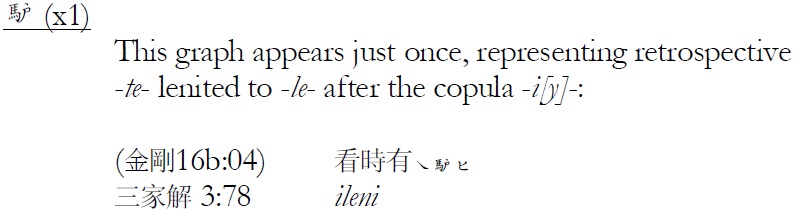

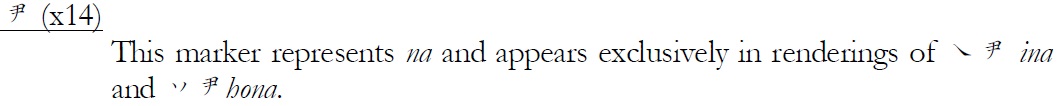

3.1. Glosses with non-traditional shapes

One obvious piece of evidence suggesting that the glossator relied heavily on the

And in yet another case the same gloss is written in

In the following example, the

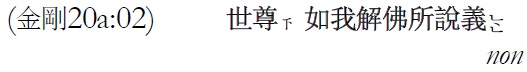

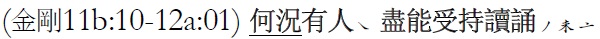

But the (or at least a) glossator of the

We seem to be dealing with an older vernacular glossing pattern for 何況 ... in N

3.3. Hybrid G losses with han’g?l ngi

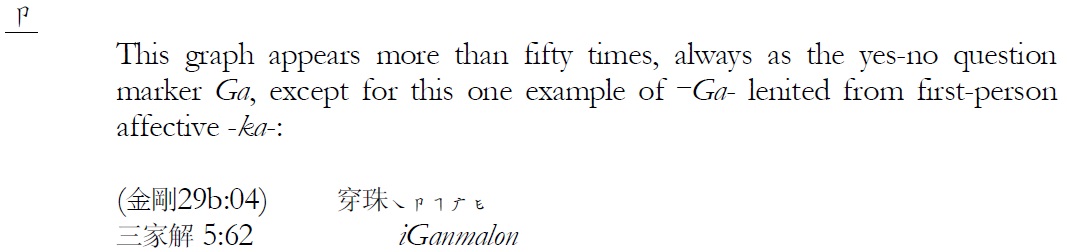

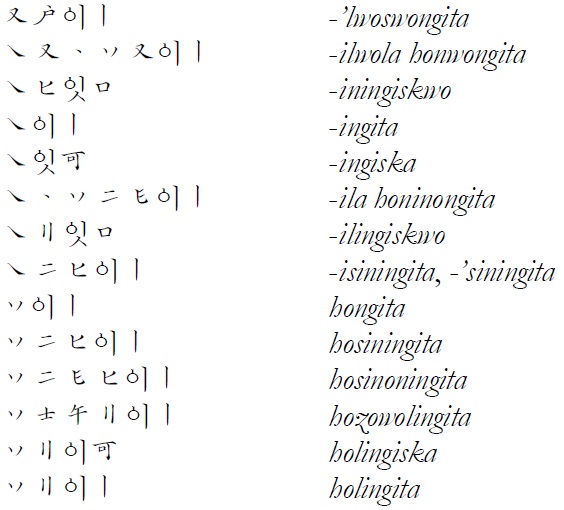

One of the more interesting features of the glosses in our text is the use of

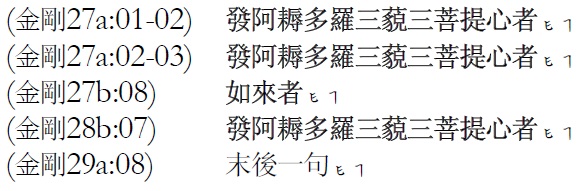

While our text is relatively consistent in deploying exactly where the

It is tempting to interpret these cases of -less glosses as holdovers (archaisms) from earlier glossed versions of our text. This is especially true in the cases of the glosses in on 不 , as these are yes-no questions (‘... or not?’) where other glossed versions of our text often leave the preceding main verb (生 in our examples here) unglossed and gloss only 不 . This suggests that the glossator of our text relied on an earlier glossed version for his glosses on 不 , but transferred the gloss with from the

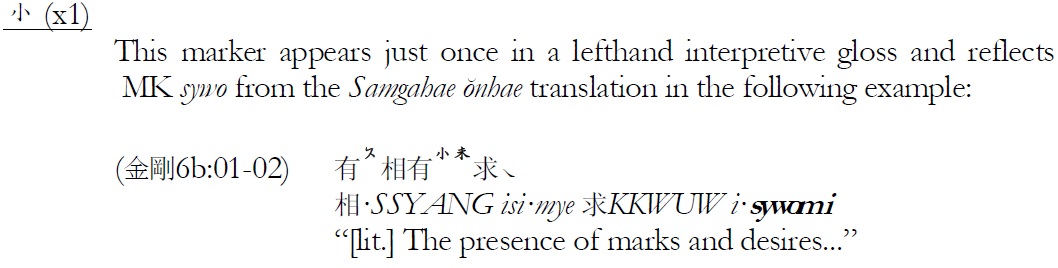

3.4. Other Partial or Whole han’g?l G losses

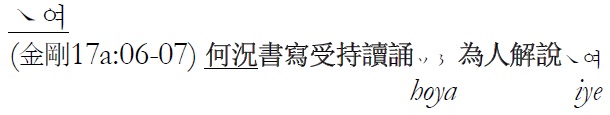

Besides the hybrid glosses seen above, there are a few other examples of glosses either partially or wholly in

The following example mixes

In two other examples, the

16Unless preceded by “[lit.],” translations from the Diamond Sūtra are taken from Price and Wong (1969), and translations of the Ch’ŏllo commentary are taken from Qian Su (2002). 17See Martin (1992:714) and 1996 for this marker.

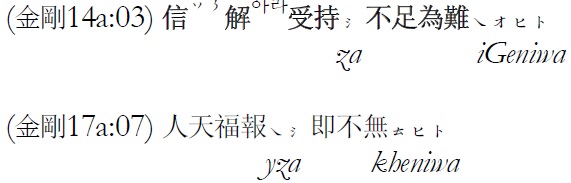

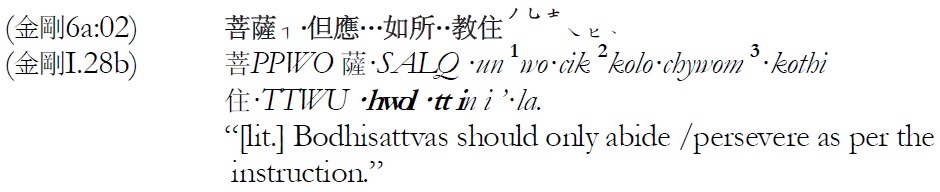

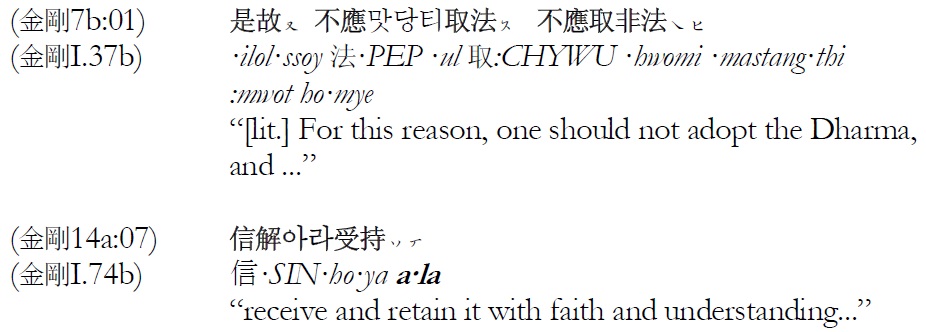

Thus far we have focused on the glosses deployed in the traditional position for ‘sequential’ (

Diachronic studies of Korean glossing practice emphasize that this sort of interpretive glossing practice that reached its peak during Koryŏ was waning by the end of that dynasty and was more or less moribund by early Chosŏn. Instead, it was replaced by a sequential glossing (also known as

It is therefore yet another interesting feature of our text that it occasionally deploys glosses―often in

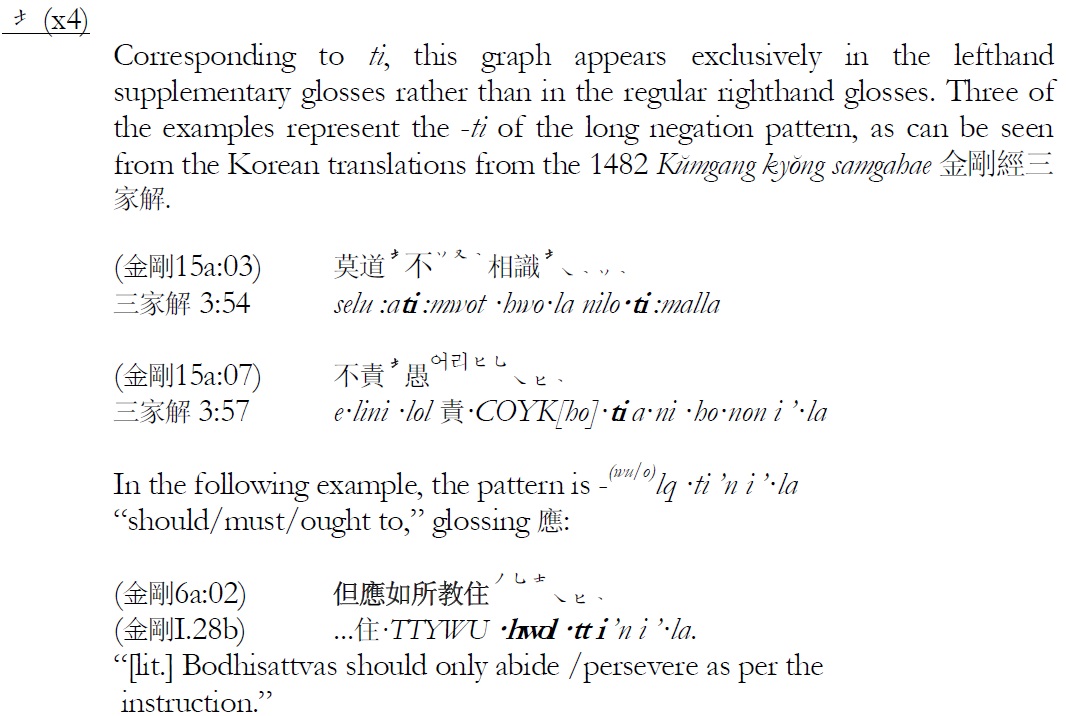

4.1 . Lefthand glosses in the Ch’?llo K?mgang ky?ng

The lefthand glosses in the

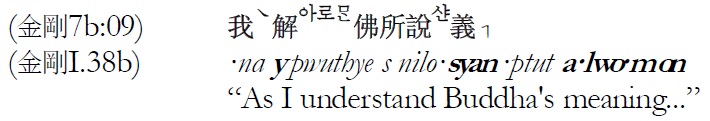

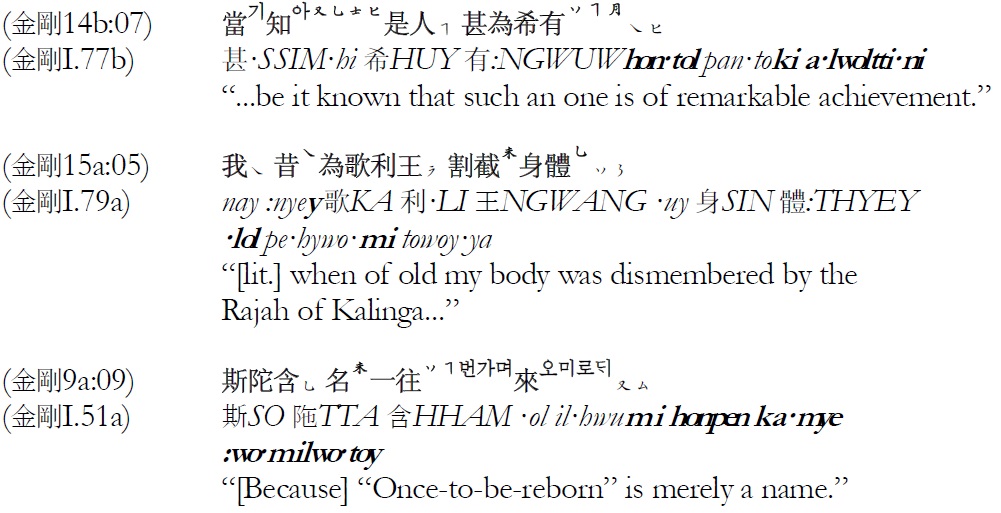

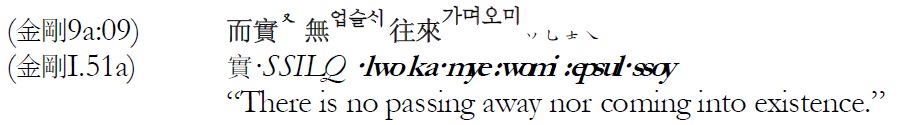

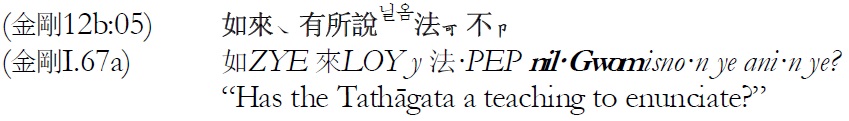

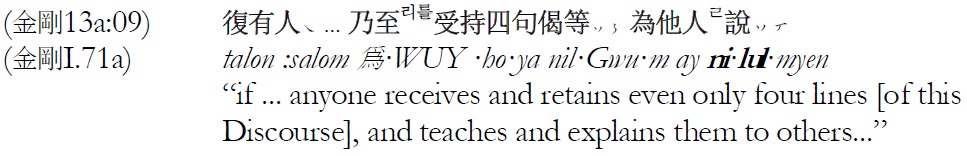

Below are some of the more interesting examples of lefthand glosses, along with the source passages and English translations. Lefthand glosses are marked in bold, as are the matching strings in the source text.

4.1.1. Glosses copied from the K?mgang ky?ng ?nhae (1464)

The very first example is of especial interest because it is also the only example in our text of true ‘interpretive’ glossing: three of the characters have dots to their left indicating the Korean word order (the dots are vertical in the original)20 :

Note also that the glossator’s analysis of the ‘should; ought to’ pattern glossing Chinese 應 suggests a contemporary analysis as

The next example and many others following it suggest that a kind of vernacular glossing (

In this particular case, the point is reinforced further by the marginal gloss in the bottom left gutter: ... (

More examples of

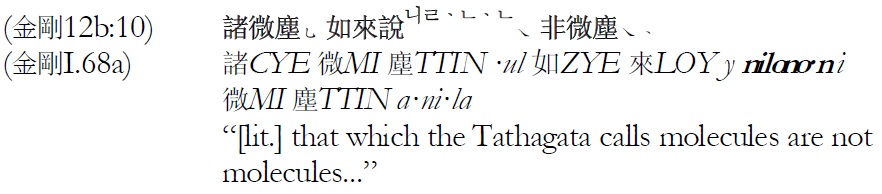

In the following example, the glossator has glossed 無 with

In the next example, there is a difference in the interrogative endings between the

And the same (very occasional) independence of spirit can be seen in the next example, where the ㄹ gloss on 他人 is not supported by the

Likewise, in the next example the glossator has subsituted for what should be :

The following righthand gloss also happens to be a nice example of the nominal use of MK processive modifier

4.1.1.1. Other glosses from the K?mgang ky?ng ?nhae

In just a couple of cases the

4.1 .2. Glosses copied from the Samgahae ?nhae translation

The most interesting glosses copied over from the

This example is interesting because the Sino-Korean pronunciation for 慧 is glossed as colloquial vernacular hyey in contrast with the artificial

4.1.2.1. Other glosses from the Samgahae ?nhae

As with glosses copied over to the lefthand margin from the

18In this regard, see especially Fujimoto (1992; 1993). 19Kŭmgang kyŏng ŏnhae examples are cited from the version available online from the Hangeul Museum at: www.hangeulmuseum.org/sub/information/bookData/total_List.jsp?d_code=00423&g_class=01. 20For discussion of similar word order glosses in an earlier edition of the Kŭmgang kyŏng from Koryŏ, see Chŏng (2007). 21The only other example in the text of a gloss not supported by either the Kŭmgang kyŏng ŏnhae or the Samgahae is the gloss here on 中 corresponding to MK ·eys: (金剛22b:03)

5. MARGINALIA IN THE CH’?LLO K?MGA NG KY?NG

The Asami edition of the

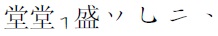

a) In the right-hand margin of 金剛 4a we find the handwritten gloss:

This glosses the characters 堂堂 in 金剛 4a:02 ... and is copied from

堂

Note, however, that the

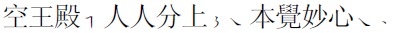

b) In 金剛 5a:04 the line ends halfway down the page with 離空王殿 after which the following is entered by hand:

Here again the glossator has converted into an abbreviated character

c) In 金剛 5b:08 the line finishes halfway down the page with:

This is followed by the following handwritten translation gloss:

Cf.

That is, the glossator has copied verbatim from the

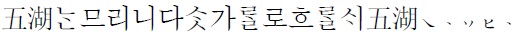

d) The short line in 金剛 6a:04 ends with 舊百花香 and is followed by the handwritten gloss:

This glosses 五湖 in the preceding line:

Once again, the gloss is hybrid, incorporating both abbreviated character

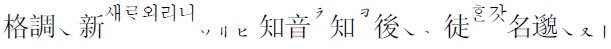

e) 金剛 12b:03-04 contains the passage:

The bottom half of line carries the gloss:

Here again the glossator has copied verbatim from the

This study of the glosses in the Asami Collection copy of the

Though the text itself was printed in 1387 at the very end of the Koryŏ dynasty, our analysis has shown that the glossator of our text relied heavily on both the 1464

But perhaps the more enduring lesson to be learned from this particular text concerns the impact that the invention of the

A related and parallel lesson would be the enduring impact of Sejong’s and especially Sejo’s projects to provide canonical Buddhist texts with authoritative

Glossed texts from early Chosŏn―particularly messy ones full of both abbreviated character

22See Plassen (forthcoming) for a useful discussion.