Under the context of neoliberal globalization, governments have pursued marketdriven economic reform policies and large firms have adopted the business model of shortterm profit maximization. In this context, intensification of labor polarization has produced growing concerns over the solidarity crisis faced by the labor movement in Korea, which reveals serious weaknesses in internal and external solidarity requiring rectification in order to overcome labor polarization. Internal solidarity of the labor movement in Korea has been weakened by union members’ attitude of self-interest toward job security and economic gain, by fragmented co-worker relations, and by intensified competition among activist factions for political power within unions. The most crucial factor constraining external solidarity of the Korean labor movement is the legacy of enterprise unionism, which has produced differentiated interest structures between organized and unorganized workers, while hindering the two worker groups from fostering a common ground of union activities and political vision. Reflexive leadership of labor movement, substantiation of industrial unionism, and fostering of communitarian activism are recommended for revitalizing labor solidarity.

The world of working people has become gloomier than ever. In contrast to the optimistic speculation of futurists, mega trends such as globalization, information society, and service economy have made the majority of working people around the globe experience worsening of employment conditions and sustained decline of decent jobs. In particular, neoliberal globalization, which has had a dominant influence on developed and developing economies over the past 30 years, has produced increasing discrepancy in wage income and decreased social protection for the working poor. To make matters worse, the global economic depression at present, triggered by the financial crisis of the U.S. economy, makes jobs and lives of the working people everywhere more vulnerable.

Here, neoliberal globalization denotes that the globalizing tendency of integrating socio-economic activities across national territories has primarily been shaped by the discourse of market-driven deregulation policy originating from “the disembedded market liberalism” of the U.S. and the U.K. in the early 1980s. The neoliberal policy paradigm, coming to the fore against the background of the “inefficiency crisis” in the welfare states, became widespread through the conservative overnments’ economic reforms in developed countries, and later diffused to developing economies under external pressure from international institutions (i.e., IMF and the World Bank). As Harvey (2005) and Bourdieu (1998) indicate, neoliberal globalization has forged “capital accumulation by dispossession” through the promotion of market-driven flexibility and dismantling of the institutionalized regime of social solidarity. As a consequence, it has intensified the inequality of economic earnings and segmentation of working life across and within countries.

Republic of Korea (hereafter Korea), which is a success model of “compressed industrialization” among developing countries, has shown an exemplar trajectory over the past 10 years of socio-economic transformation influenced by neoliberal globalization. The 1997 economic crisis imposed IMF-driven neoliberal reforms, including flexibilization of the labor market as well as full-scale opening of product and capital markets throughout Korea. Furthermore, Korea’s labor regime was greatly impacted by extensive restructuring and massive downsizing in the public and private sectors. Despite the economic recovery after 1999, Korea has ever since been confronted with the crucial problem of labor polarization as clearly evinced by a sharp increase in non-regular workforce and the widening disparity of employment conditions between regular (male) employees working for large firms and the remainder of the workforce. As a consequence, growing concern over “the crisis of labor solidarity or social justice” and “democracy without labor” in Korean society is the product of labor polarization (Lee 2005; Choi 2005). In fact, labor polarization reflects the moral exclusion of non-regular laborers and workers at small- and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) from organizational and institutional protection, which exposes the developmental lag of social democracy in Korea’s political system by excluding representation of the interests of this marginalized working group (B. Lee 2008). Moreover, labor polarization engenders social disintegration as exemplified by a rapid rise in crime, suicide, and divorce, while eroding the sustainability of national economic growth. As such, labor polarization has been a destructive force undermining social solidarity of Korean society, which is propelled by neoliberal globalization over the past 10 years.

This paper is to review the crucial issue of labor polarization in association with solidarity crisis in the Korean labor movement. The next section delineates the trends and driving forces of labor polarization since the 1997 economic crisis. The third section diagnoses the problematic facets of the labor movement from the theoretical lens of solidarity. The last section concludes with some suggestions for revitalizing solidarity of labor movement in Korea.

Trends and Driving Forces of Labor Polarization in Korea

Korean economy became incorporated into neoliberal globalization since the economic crisis of 1997. Confronted with this economic crisis which came as a complete shock to the labor market in Korea, most Korean companies that had maintained the internal labor market policy of “life-time employment” in the pre-1997 era of sustained economic growth undertook extensive business restructuring and massive downsizing in an unprecedented manner. This resulted in fundamental changes in employment relations in the Korean labor market. According to a 2000 survey of listed corporations conducted by Korea Labor Institute (KLI), the percentage of companies that took action to downsize the number of employees during the period of this economic crisis is reported to be 66%, demonstrating how extensive corporate restructuring was at the time (Park and Roh 2001). The same survey shows that 74% of all responding companies created spin-offs and 57.6% outsourced part of their business. During the time of economic recovery in 1999, these companies recruited non-standard labor to fill positions formerly held by regular labor.

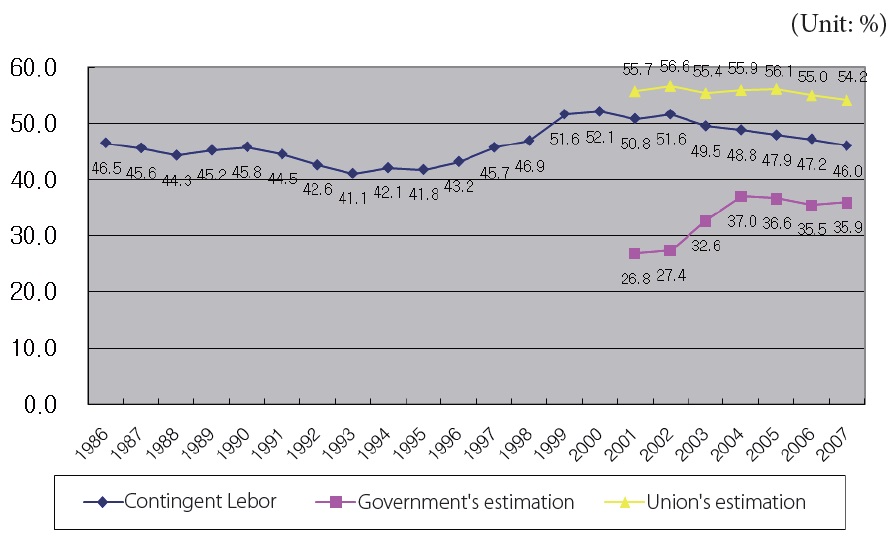

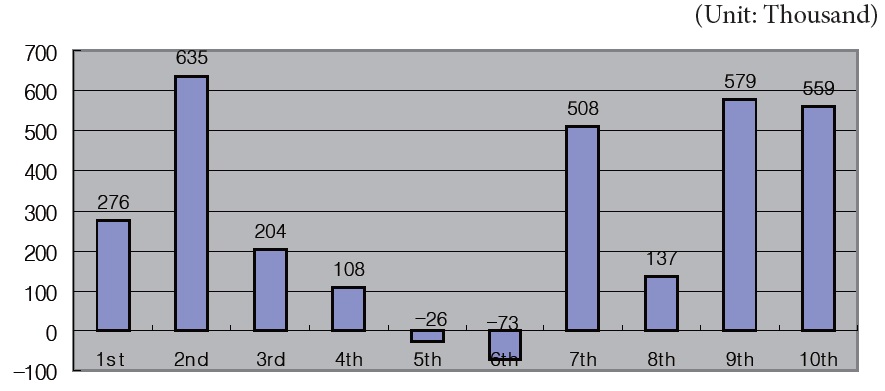

Korean labor market experienced a sharp rise in unemployment to 7% during the economic crisis and is witness to the decline of unemployment to 3% since the economic recovery in the new millennium. However, the problem with the Korean labor market then was the worsening of employment structure, mainly derived from a sharp decline in desirable jobs and the widening disparity between desirable and undesirable jobs. Loss of desirable jobs at large firms was mainly due to management’s determined policy to carry out downsizing and outsourcing. The employment size of large firms with over 500 employees decreased from 2.1 million in 1993 to 1.3 million in 2005. As a result, large-firm workforce declined from 17.2% to 8.7% in the total wage-labor population during the same period (Kim 2005). On the other hand, the number of non-standard workers grew sharply after the economic crisis. Thus, excessive use of and discrimination against disposable employees has become a debatable issue in Korean society. As illustrated in figure 1, the percentage of non-regular employment has increased from 26.8% in 2001 to 35.9% in 2007 according to official government statistics, while labor unions estimate that the number has stayed between 55.7% and 54.2%.1 Nearly 90% of non-regular workers are employed at small firms with less than 300 employees. Moreover, a sustained reduction in the number of manufacturing jobs is associated with worsening job quality; between 1997 and 2007, the percentage of employment in the manufacturing sector dropped from 21.4% to 17.6%. These factors combined resulted in decreased middle-income jobs as shown in figure 2, thereby producing growing concern over labor polarization as well as the dismantling of the middle class in Korean society.

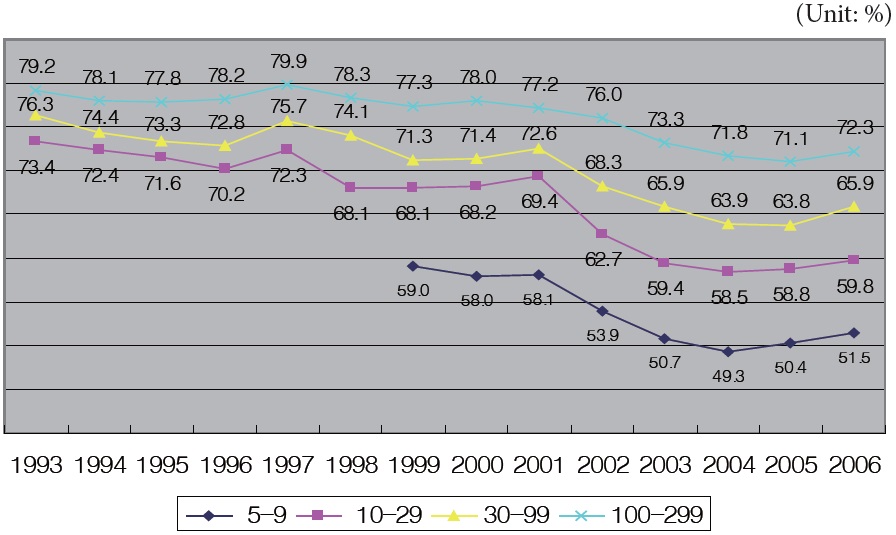

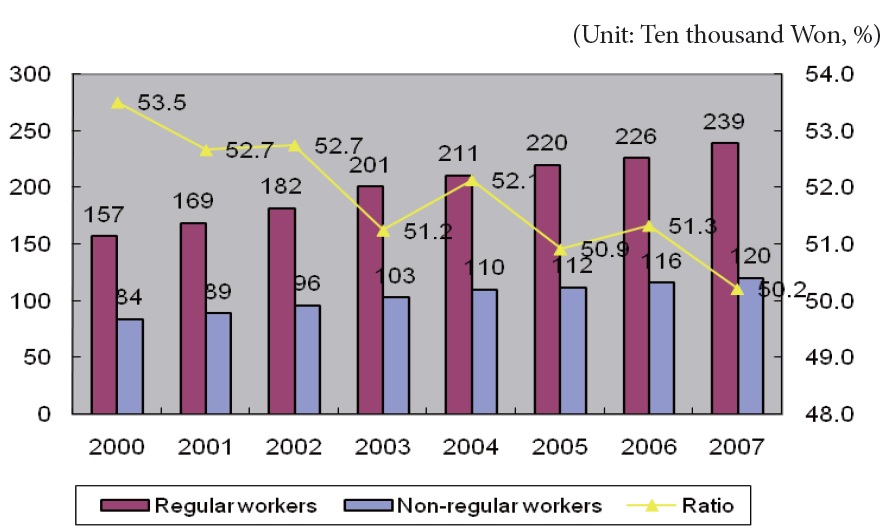

Polarization of the labor market is evinced by the growing gap in overall employment conditions, including wages and fringe benefits, between the primary sector consisting of regular workers at large firms and the secondary sector consisting of regular workers at SMEs and non-regular employees. Figure 3 demonstrates the growing wage discrepancy between large and small firms from 1993 to 2006. For instance, monthly wages at small firms with 10-29 employees declined from 72.4% of in 1994 to 59.8% in 2006 in comparison to large firms with over 500 employees. Moreover, the wage gap between regular and non-regular workers has increased during recent years, to the point that monthly wages of non-regular workers have dropped from 53.7% in 2000 to 50.2% in 2006 in comparison to those of regular workers, as illustrated in figure 4.

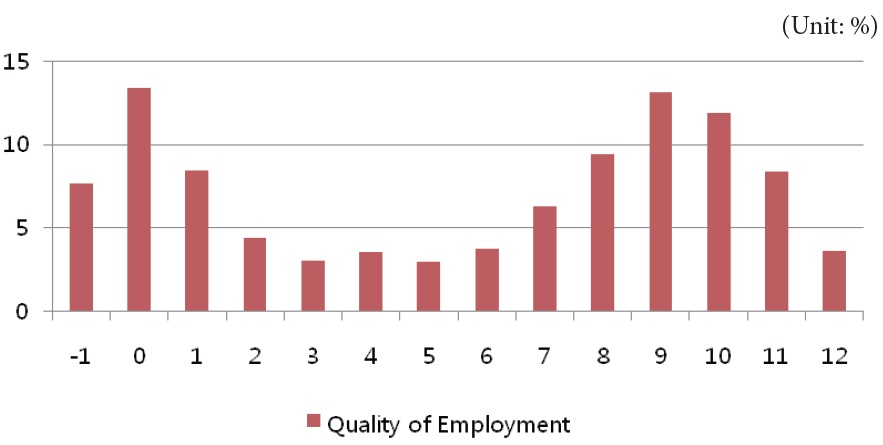

Labor market polarization is also evident in workers’ fringe benefits and human resources development. Discrepancy in fringe benefits and training between large and small firms has been constant over the past 10 years. Large firms with over 1,000 employees expend twice more on fringe benefits and eight times more on training than small firms with 30-99 employees. Most non-regular workers are excluded from social welfare and labor standards. About 30% of these workers benefit from statutory welfare programs such as national pension, medical insurance, and employment insurance. Only 15%-20% of non-standard workers are protected by statutory labor standards, including extra work premiums and severance pay. As a consequence, as shown in figure 5, the quality of employment among working people exhibits a “bi-polar” distribution, which demonstrates the polarized segmentation of labor market in Korea.2

An additional problem with polarized labor market is the lack of job mobility between primary and secondary sectors. Many studies have shown that non-regular jobs are traps rather than “stepping stones” to regular jobs because non-regular workers are entrapped in their marginal jobs rather than being able to move upward to regular positions (Nam and Kim 2000; Han and Jang 2000). The effect of segmented labor market structure is also identified in the school-to-work transition for youths with college degrees (Kim and Chun 2004).

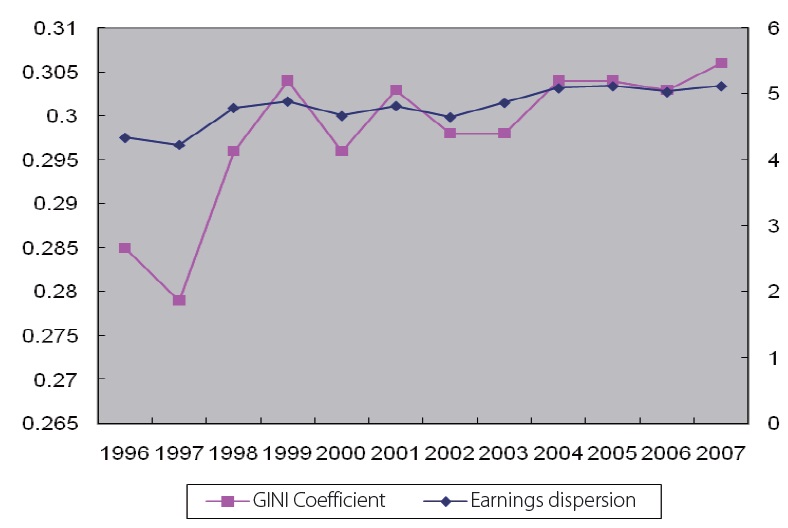

Labor polarization has not only aggravated income distribution in that both GINI coefficients and earnings dispersion, estimated by the relative ratio of the top 20% urban household income to the bottom 20% income households over the past 10 years, have increased as illustrated in figure 6, but it also produced growing concerns over social disintegration. In fact, divorce rate has soared from 59,300 in 1993 to 124,600, while suicide rate has increased from 1.06 million to 2.42 million in the same period. The number of heinous crimes grew annually by an average of 11.5% between 1997 and 2004.

Various factors have contributed to labor market polarization in Korea. The structural transformation of the Korean socio-economic system during the 1990s, and particularly in the aftermath of the 1997-1998 financial crisis, is associated with labor polarization. The wave of globalization that has infiltrated Korean economy has fortified the public discourse into justifying the “race-to-the-bottom” market competition and has hence created hegemonic dominance of “winner-take-all” mentality among the ruling elite and in the mass consciousness. Moreover, the advent of the service society and higher education of national manpower have spurred on individualization of working people and fragmented the organizational and psychological foundation of labor solidarity. Ironically, political democratization that has evolved since 1987 has led to intensification of social inequity by fostering domination of a new power bloc comprised of chaebols, bureaucracy, and conservative media equipped with neoliberal developmentalism in the era of globalization. The democratized state has been deprived of policy tools and the capacity to regulate economic segmentation between large leading firms and subcontracting SMEs under the context of deregulated open economy. Likewise, political democratization, which neutralizes the state’s authoritarian labor control policy, has led to increased discrepancy in employment conditions between organized and unorganized workers. Confronted with growing labor polarization since the economic crisis, Korea’s democratic government took a stance of market

1There have been intense debates on the size of non-regular workforce based on the Economic Active Population-Supplementary Survey conducted annually by the National Statistics Office since 2000. The difference between the government’s statistics and labor union’s estimation is due to whether workers under recurrent renewal of temporary employment contract should be incorporated into the number of non-regular workforce. Labor unions insist that those workers should be categorized as non-regular labor, because they have insecure employment status and work under inferior working conditions like non-regular laborers. 2The quality of employment is measured by combining 13 items covering provisions on social welfare, protection of statutory labor standards, and employment conditions in the Economic Active Population-Supplementary Survey.

Solidarity Crisis in Korea’s Labor Movement

Labor polarization has not only posed a crucial problem of economic inequity among working people, but it also undermines the foundation of solidarity for Korea’s labor movement. Korean labor movement developed the tradition of resistant solidarity to protect workers’ human rights from the authoritarian state’s labor control policy until 1987, and thus, it achieved explosive growth under the context of political democratization from the late 1980s to the early 1990s (Kim 2008). It has been confronted with serious challenges arising from neoliberal globalization since the mid-1990s, however, particularly in the aftermath of the 1997 economic crisis. As exemplified by the growing trend of labor polarization, labor movement has been unable to cope with segmentation of working people which resulted from neoliberal restructuring led by the government and business groups over the past 10 years. Moreover, it is reduced to interest group unionism of protecting the interests of organized workers and of ignoring to represent the unorganized, thereby becoming victim to a “recruiting trap of organizational exclusion” (Zoll 2004) and being accountable for labor polarization to some extent. As a consequence, it now finds itself facing a “crisis of solidarity” (Lee 2005).

According to Zoll (2000), solidarity is conceptualized in terms of the following dual aspects: first is the capability of group members to behave as unified actors in relation to other members; second is the inter-dependence and coalition among different groups. In labor movement, the former implies internal solidarity among union members, while the latter connotes external solidarity with unorganized working people and other social movements. Internal labor solidarity is primarily based on an interest community and collective identity derived from the union members’ pursuit of identical interests and sharing of daily working experiences (Shelby 2002; Michels 1962). This type of solidarity has been stressed by labor unions as an organizational unity for mobilizing power to pressure employers into accepting their demands. By contrast, external solidarity presumes different groups (i.e., regular and non-regular workers, or labor unions and NGOs) to bridge and cope with different interests and identity by building a common ground of political vision and mutual trust (Stjernø 2004; Hirsch 1986).

Solidarity, internal as well as external, is the core source of labor unions’ power and social leverage; the former represents the extent of organizational cohesiveness and mobilization among union members while the latter signifies the degree of hegemonic force and societal legitimacy accredited to labor unions. A common and crucial precondition for fostering internal and external solidarity is reliable leadership for collective cohesion and strong relationships among organizational members and across different groups, effective communication for mutual understanding and shared framing, continuous contacts to nurture psychological ties and intimacy, and social norms to regulate the free-rider problem (Shelby 2002; Hodson et al. 1993; Hechter 1987; Jung 2003). In particular, external inter-group solidarity among different status groups requires group leaders’ political or ideological initiatives to promote collective altruism among privileged group members (Stjernø 2004; D’Art and Turner 2002).

From a theoretical viewpoint of solidarity as outlined above, the labor movement in Korea reveals serious weaknesses in building internal and external solidarity for overcoming labor polarization. Korea’s labor union movement, which grew explosively in the aftermath of the 1987 democratization movement and through which labor unions showed off militant mobilization that attracted worldwide attention in the 1990s through its exertion of societal influence, has now lost its organizational power. Decline of the labor movement is exemplified by the falling trend in union density from 18.6% in 1989 to 10.0% in 2006. Union members, particularly of large unions, were very active in abolishing militaristic shop floor control of the pre-1987 era and in improving economic compensation and working conditions by partaking in union-led collective action until the early 1990s, but they became inactive in union activities since the mid-1990s as they enjoyed economic benefits gained through previous militant actions. During the 1997 economic crisis, union members saw their colleagues lose jobs due to massive downsizing, and their confidence in the organizational capacity and leadership of their unions to defend their jobs from employer-led lay-offs was shaken. Thus, they have since become more interested in preserving not only their own job security but also in economic gains to be made from collective bargaining to provide against future job loss. Under this context, intimacy on the shop floor among co-workers has transitioned to emotional detachment and organizational fragmentation. Moreover, union leadership, particularly at large firms, has often been weakened by intensified competition among activist factions to pursue political power within the union, which furthers union members’ indifference toward the labor movement. These factors have combined to damage the union’s internal solidarity-organizational cohesion and mobilizing capacity-over the past 10 years.

Labor movement in Korea has revealed a more crucial problem of external solidarity by being confronted with the growing trend in labor polarization between the organized at large firms and the unorganized at SMEs and non-regular employment. As of 2006, union density of the workforce employed by small firms with less than 30 employees is only 3.8%, and that of non-regular workforce is only 2.8% (Lee and Kwon 2008). By contrast, union density of the workforce employed by large firms with 300 or more employees is 35.5%. Given the minimal level of union representation of SMEs and non-regular workers, the two national centers—Federation of Korean Trade Unions (FKTU) and Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU)—have launched a number of campaigns for social reforms to protect unorganized labor force; they have also made efforts to organize them, but most of their efforts have been for naught. KCTU has put conscious effort into the organizational transformation toward industrial unionism since 1998, and has made 75.6% of its members affiliated with industrial unions. Industrial unions, however, have made little progress in representing or organizing these unorganized workers of SMEs and nonregular employment, except a few success cases of the Korea Health and Medical Workers Union and the Korea Metal Workers Union.

The most crucial factor constraining external solidarity of Korean labor movement is the legacy of enterprise unionism. The enterprise union structure, which was enforced by the military government in the early 1980s as a means to control and suppress organized labor, served as an organizational foundation to mobilize

Under the context of neoliberal globalization, governments of many countries have pursued market-driven economic reform policies, and firms have adopted the business model of short-term profit maximization. In this context, intensified labor polarization is common in most industrial societies as observed in the growing discrepancy of economic compensation and employment conditions between organized and unorganized workers. The driving force behind labor polarization comes chiefly from neoliberal globalization and market-driven deregulation and restructuring undertaken by governments and employers during the past 30 years. However, labor unions are not unrelated to generating labor polarization. Labor unions in most countries have lost their organizational power and cohesiveness, exemplified by declining membership and differentiated interests of union members, and hence, experienced the deterioration of their class representativeness and societal voice as a result of narrowly focusing on activities to protect members’ interests and their inability to cope with labor polarization. As a consequence, labor union movements in many industrial societies are confronted with solidarity crisis. Korean labor movement is not an exception; rather, it is an exemplar case. Korean labor unions, which have been known for their militant activism to gain socio-economic reforms for the working class since the late 1980s to the mid-1990s, are now showing crucial problems of fragmented and self-interested membership as well as exclusionary attitudes toward unorganized irregular workers. As such, Korea’s labor movement has been inactive and incapable of securing solidarity of all of the working class because it is undermined by neoliberal restructuring led jointly by the government and businesses.

Revitalization of solidarity in the labor movement is a key precondition to coping with labor polarization. Several suggestions can be made for rebuilding solidarity in the labor movement in general and in Korea in particular. First, revitalization of solidarity can start with reflexive leadership of labor movement. In order to rebuild internal solidarity (members’ unity) within labor unions to overcome individualized interests, new union leadership must restore communitarian consciousness of the members by developing and activating reflexive discourse to replace entrenched neoliberal orientation of the logic of race-to-the-bottom competition and free-riding norms. Furthermore, new leadership is required to make conscious efforts to overcome a differentiated interest structure in order to forge external solidarity between organized and unorganized workers. New leadership should also regain the confidence of union members and the unorganized in labor movement in order to achieve organizational integration and expansion by developing viable strategies to “win” the contest against employers and the government.

Second, substantiation of industrial unionism with political vision and active praxis of solidarity is necessary for overcoming the legacy of enterprise unionism, which has shaped the narrow-minded interests of union members and has segmented the social relations of the organized and unorganized. As Zoll (2000) indicates, industrial unionism should be built on “organic solidarity” to embrace varied interests among the workforce from different sectors and employment status rather than resorting to “mechanistic solidarity” based on identical interests, upon which enterprise unionism has been based.

Third, in order to fortify external solidarity, the labor movement needs to focus on fostering community-based activism that promotes common grounds for psychological ties and social intimacy; as well, a differentiated interest structure must be transcended beyond the enterprise boundary. Social network of intimacy in community activism could be fostered by a variety of communal activities, including workers’ families and local NGOs, aimed at transforming workers’ individualized lifestyle into collective identity and culture. Moreover, it is important to make conscious effort to institutionalize the norms of solidarity for de-marketizing co-worker relations in the realm of daily life inside as well as outside the shop floor.