While there is a high degree of convergence in linguistics in the treatment of the progressive as an aspect, the English progressive is unusually wide in its range of uses. It is, therefore, illuminating to distinguish ‘aspectual’ progressives, which involve a universal or near-universal notion of aspect, from ‘non-aspectual’ progressives, which reflect a parochial feature of English. Of these two, the main focus of the present paper is on the latter.

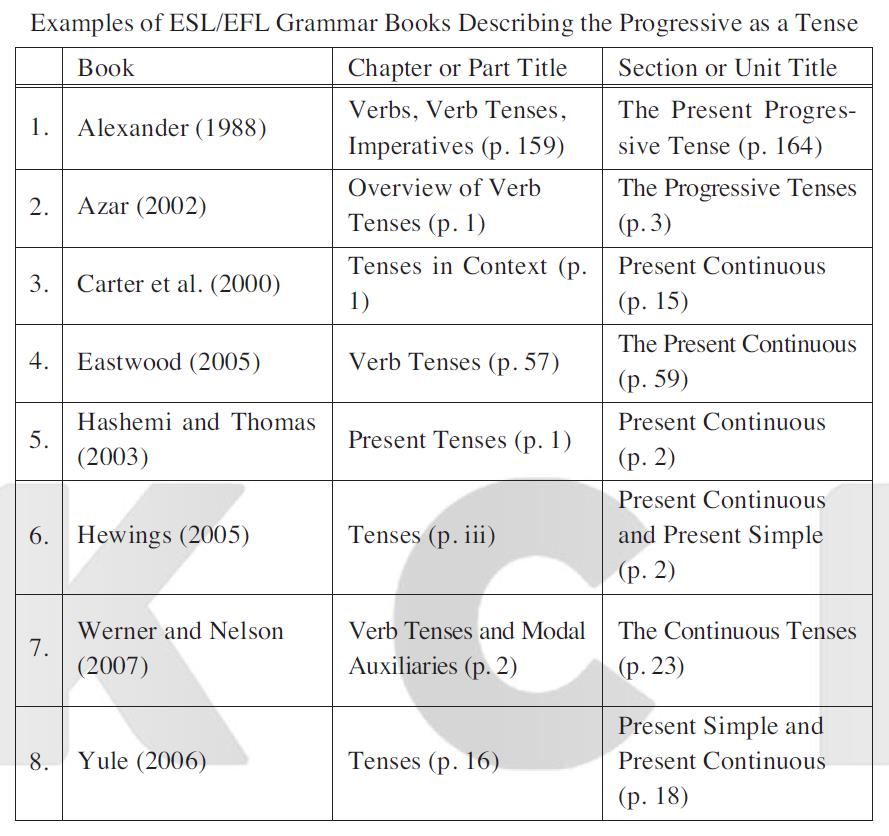

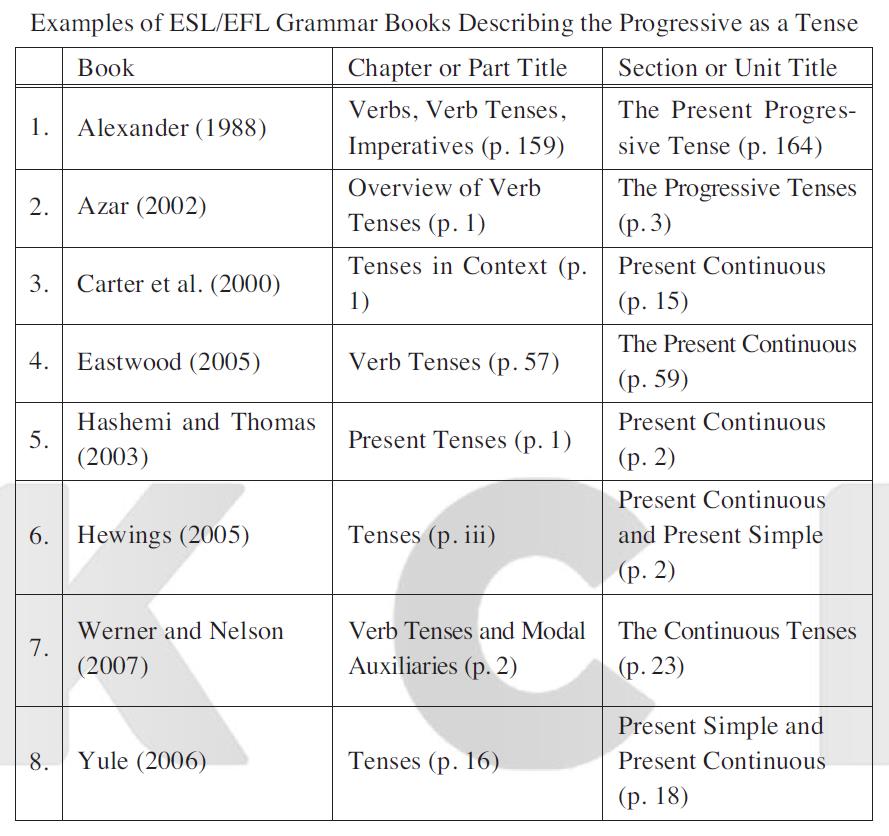

The motivation of this paper stems from the fact that in some ESL/EFL (English as a second/foreign language) grammar books, the progressive has been mistakenly described as a tense, as summarized in Table 1. The cause of this misconstruction is partly due to a lack of understanding of the binary distinction between aspectual and non-aspectual progressives. The purpose of this paper is to clarify the contrast between aspectual and non-aspectual progressives and identify some of the core properties that distinguish one from the other. Section II lays out the relevant background of this study. Section III discusses briefly the canonical meaning of the progressive aspect along with the fundamental differences between aspect and Aktionsart. Sections IV through VI examine some representative examples of non-aspectual progressives: the progressive futurate, the habitual progressive, and the experiential or interpretative progressive.

[Table 1] Examples of ESL/EFL Grammar Books Describing the Progressive as a Tense

Examples of ESL/EFL Grammar Books Describing the Progressive as a Tense

This paper accepts S. Pit Corder’s view of applied linguistics, namely as mediator between linguistics and language teaching:1

Following Corder (1973: 10-11), language teaching is interpreted here “in the very broadest sense, to include all the planning and decision-making which takes place outside the classroom.”2 Corder’s (1973) broad notion of language teaching is also very much in the same spirit as the definition of pedagogic (or pedagogical) grammar adopted by Davies (1999: 24):

The ultimate goal of this study is bridging the gap between theoretical linguistics and descriptive and pedagogical linguistic activities. The legacy of crossing boundaries in these two seemingly disparate areas can be traced back to the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as noted by Pullum (2002):

Pullum (2002) further deplores the fact that by the end of the twentieth century this type of alliance had been dissolved, and ascribes the growing gulf between theoretical linguistics and descriptive and pedagogical linguistic activities to “over-radical anti-prescriptivism[,] . . . contempt for applied fields[, and] failure to produce comprehensive descriptions,” among other things.

Having sympathy with this point of view, this paper aims to narrow the existing gap between theoretical linguistics and descriptive and pedagogical linguistic activities. Given this background, this study will be of relevance for both linguists and English language professionals such as ESL/EFL textbook writers or English language teachers, who need a comprehensive understanding of English progressive constructions.

1S. Pit Corder was “an important innovator in the field” of applied linguistics, and was “largely responsible for the development in the UK of specialised courses in applied linguistics” (Davies 1999: 6). Applied linguistics is a wideranging field and people interpret the term ‘applied linguistics’ differently. In fact, it has been “the subject of much argument about definition,” as Brumfit (1988: 3), among others, notes. 2This paper does not attend to classroom teaching. For some classroom activities concerning the English progressive, see Richards (1981) and references cited therein.

III. Aspectual versus Non-aspectual Progressives

For a long time there was no consensus among linguists with respect to the general grammatical status of the progressive in English. Zandvoort (1962), for example, argues that the English progressive is not an aspect at all, since it differs in many respects from the Russian imperfective. It is also interesting to note that Jespersen (1924: 277, 1931: 164, 1933: 263) refers to the progressive as the ‘expanded tense,’ whereas Sweet (1892: 103) employs the name ‘definite tense’ to describe the progressive. However, the usual approach today is to treat the English progressive as aspect.

The study of aspect in English has given rise to many controversial issues of which the more tangled are the term ‘aspect’ itself and its companion term ‘Aktionsart.’3 As Tobin (1993: 4) notes, “[a]spect has almost as many definitions as there are linguists who have attempted to deal with it, particularly those linguists trying to capture the complex subtleties of ‘aspect in English.’” Furthermore, although the differentiation of aspect and Aktionsart is a useful one of long-standing relevance (Brinton 1988: 3), more often than not, it is ignored or blurred and some scholars such as Verkuyl (1972, 1989, 1993) have argued against distinguishing the two.

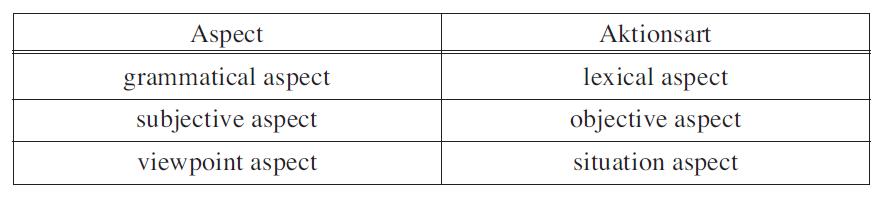

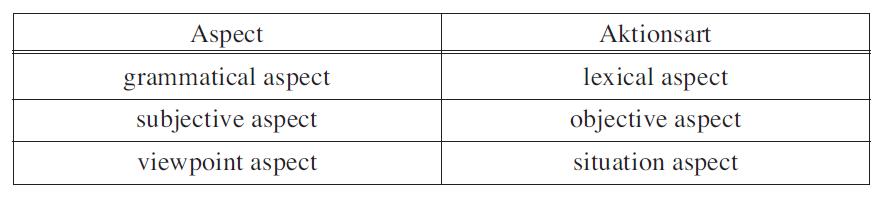

The distinction between aspect and Aktionsart has been approached from many different directions, as shown in Table 2 (see Brinton 1988: 3, among others).

[Table 2] Aspect versus Aktionsart

Aspect versus Aktionsart

The traditional view is that aspect is grammatical while Aktionsart is lexical in English (Tobin 1993: 7).4 Aspect is grammatical because by and large, it is expressed by “verbal inflectional morphology and periphrases” (Brinton 1988: 3). In contrast, Aktionsart is generally expressed by “the lexical meaning of verbs and verbal derivational morphology” (Brinton 1988: 3). The dichotomy between aspect and Aktionsart in terms of ‘subjective’ and ‘objective’ can be explained in the following way. Aspect is subjective in that the speaker/writer chooses a particular viewpoint or perspective on a situation. Aktionsart, on the other hand, concerns the more or less objectively given type of situation.5 Smith (1983, 1997), among others, refers to the former as ‘viewpoint aspect’ and the latter as ‘situation aspect’. To summarize, aspect is “a matter of the speaker’s viewpoint or perspective on a situation,” whereas Aktionsart is “the character of the situation named by a verb” (Brinton 1988: 3).

With this background, let us now turn to the question of what counts as the progressive aspect.6 Binnick (1991: 281-90) and Kabakčiev (2000: 168-75) discuss the difficulty embedded in attempts at a definition of the progressive involving a single basic meaning. Nonetheless, the following extracts show that a generally agreed-upon meaning assignable to the progressive is ‘ongoingness’:

In a nutshell, the primary function of the progressive is to present a situation as ongoing. We will refer to this strictly aspectual use of the progressive as ‘aspectual progressive.’

There are, however, other cases of the progressive in which the meaning of ongoingness (i.e., the ‘process’ element of meaning) is lacking, or to put it less categorically, not salient, as will be argued at some length in sections IV - VI below. The examples in (3) offer just a glimpse into the multiplicity of uses that English progressive constructions have. Compare (3b-c) with (3a), which is the aspectual progressive or the progressive proper.8

The uses of the English progressive that are not, in a strict sense, aspectual will be called ‘non-aspectual progressive.’9 In the following sections, we will examine some of the non-aspectual progressives in English. We begin with uses such as (3b) and (3c) in turn and then consider a nonaspectual use that is not given in (3).

3The term ‘aspect’ corresponds to the Russian word vid ‘view’ (Brinton 1988: 2, Binnick 1991: 136). Instead of the term ‘Aktionsart,’ some linguists prefer to use terms such as ‘eventuality (type)’ (Bach 1981: 69, Filip 1999: 15) or ‘actionality’ (Bertinetto 1994: 392, 415). 4See, however, Kreidler (1998: 198), who claims that aspect is both grammatical and lexical. 5One might argue that Aktionsart also concerns the addition of a subjective element. This line of thinking is summarized in the following passage: In a certain sense, [A]ktionsart is as ‘subjective’ as aspect. That is, in order to name a situation, a speaker must conceptualize that situation in a particular way. Different speakers may choose to conceptualize the same situation differently. (Brinton 1988: 247) One piece of evidence in support of the subjective nature of Aktionsart comes from Dahl (1981: 83). Seeing John sitting at his desk, we may answer the question What is he doing? by using an activity, as in (i) or an accomplishment, as in (ii). (i) He is writing. (ii) He is writing a letter. The same point is made by Galton (1984: 71). One may describe one and the same situation as a state or an activity. For example, “Jane is in the swimming-pool reports a state while Jane is swimming reports an activity” (Galton 1984: 71). Yet as Brinton (1988: 247) freely concedes, “this is a problem outside of the linguistic domain, strictly speaking.” 6The progressive aspect is sometimes called the ‘durative’ or ‘continuous’ aspect (Quirk et al. 1985: 197). 7Throughout this paper, the term ‘progressive aspect’ will be reserved for aspectual progressives only, while ‘progressive construction’ (be + V-ing) will be applied to both aspectual and non-aspectual progressives. What Huddleston (2002) calls ‘progressive aspectuality’ is equivalent to ‘progressive aspect’ in our terms. The term ‘progressive aspect’ in Huddleston’s (2002) sense corresponds to ‘progressive construction’ in our terms (seeHuddleston 2002: 162-163). 8Not only the examples in (3) but also the corresponding descriptions in the brackets (including the word ‘futurate’) are repeated from Sag (1973: 85). For more details on the word ‘futurate,’ see footnote 10. 9Since the aspectual/non-aspectual distinction largely depends on how one defines the progressive aspect, there is, naturally, room for disagreement on the classification of a particular use as non-aspectual.

IV. The Progressive Futurate

As the examples in (4) illustrate, one of the striking properties of English is that the present progressive as well as the simple present can be used to express future time reference.

In this respect, English differs from other languages with a grammatical progressive such as Spanish. For example, Spanish does not permit (5b), otherwise parallel to (5a), even if it allows a future use of the simple present.11

This use of the progressive is regarded as a non-aspectual one (Huddleston 2002: 171, among others), on the grounds that its meaning cannot be accounted for in terms of ongoingness. One might say that in some regards, there is a sense of ongoingness by arguing that the progressive futurate refers to matters that have already been settled or decided at the time of the utterance. Yet, the event of leaving described in (4b) or (5a) is not ‘in progress’ in a strict sense.

Although in (4), it is difficult to pin down the difference in meaning between the non-progressive and the progressive (Huddleston 1984: 156), in some other cases, the contrast between the two is noticeable. For example, in (6b)

In sum, “the progressive tends to be used for the relatively near future” (Huddleston 2002: 171).

Another restriction imposed on “the ‘futurate’ use” (Goldsmith and Woisetschlaeger 1982: 88) of the progressive is that it is generally felicitous in cases where human agency or intention is involved (Leech 1987: 64, Huddleston 2002: 171). Accordingly, the anomaly of (7b) is attributed to the fact that the subject is inanimate, unlike the human subject in (8).12

Finally, it is worth digressing to consider progressive constructions that are related to the case at hand but cannot be treated under the heading ‘progressive futurate.’ As the examples in (9) indicate, the aspectual/nonaspectual distinction is found not only in present progressives but also in ‘future progressives’ (

Whereas (9a) means that “the lunch will be still in progress at the time of our arrival,” this sort of interpretation is not possible in (9b), where the progressive just indicates that “the matter has already been settled rather than being subject to decision now” (Huddleston 2002: 172).13 What is significant about these patterns is that some progressives may be ambiguous between an aspectual reading and a non-aspectual reading. On the aspectual reading, (9c) is construed as saying that “we will already be flying to Bonn when the meeting ends” (Huddleston 2002: 172). On the non-aspectual reading, “the

10The term ‘progressive futurate’ is taken from Huddleston (2002: 171). Unlike Huddleston (2002), Dowty (1979: 154) employs the name ‘futurate progressive’. As Dowty (1979: 188) points out, the futurate progressive or the progressive futurate (John is leaving town tomorrow) must not be confused with the ‘future progressive’ (John will be leaving town tomorrow). 11Goldsmith and Woisetschlaeger (1982: 88) note that Spanish, not English, is the unmarked case. As the examples in (i)indicate, in Spanish, the simple present can be used to express future time reference. (i) a. Me voy dentro de cinco minutes. I leave in five minutes ‘I leave in five minutes.’ b. John se va mañana. leaves tomorrow ‘John leaves tomorrow.’ We wish to thank Casilda García de la Maza for help with Spanish. 12The judgement in (7b) is not repeated from Huddleston (1984: 157). Rather, it is taken from Leech (1987: 64) and Dowty (1979: 161), who assign an asterisk to analogous sentences, as in (i). (i) a. *The sun is rising at 5 o’clock tomorrow. (Leech 1987: 64) b. *The sun is setting tomorrow at 6:37. (Dowty 1979: 161) Huddleston (1984: 157) just remarks that (7b) is not normal. In Huddleston (2002: 171), the symbol ‘#’ (meaning ‘semantically or pragmatically anomalous’) is assigned to a sentence akin to (7b), as in (ii). (ii) #The sun is setting at five tomorrow. (Huddleston 2002: 171) 13The salient interpretation of the non-progressive counterpart of (9b), Will you go to the shops this afternoon?, is as “a request to you to go to the shops” (Huddleston 2002: 172).

In English, the present progressive may express not only futurity but also habituality. For illustration, consider (3), repeated below as (10).

Given that habits are generally expressed in English by the simple present, as the examples in (11) show, a natural question arises as to whether there is any difference between the habitual progressive and its non-progressive counterpart.

There are at least two distinctive features of the habitual progressive. First, habitual progressives with adverbs such as

According to Leech (1987: 34), (14a) is understood as meaning (15a), while (14b) has the rough interpretation in (15b).

In sum,

Notice also that habitual progressives of this sort have an “emotional colouring” (Jespersen 1931: 180-181), as remarked by several authors.14 For example, Huddleston (1984: 156) notes that unlike the non-progressive (13a), the progressive (13b) carries an emotive element in that the speaker finds their behavior somewhat tiresome. The implicatures of these patterns are most cogently stated by Leech (1987).

A second sort of characteristic is that habits in the progressive may refer to temporary habits, or those holding for a limited period, as the following examples indicate:

Even when there is no adverbial like

This contrast is also exemplified by the near-minimal pair in (18).

With regard to (18b), it is perhaps worth mentioning that Huddleston (2002: 167) classifies a closely similar sentence such as (19) under the heading ‘temporary state.’15

However, this seems to be a misconceived strategy, given that states and habits should not be lumped together. As Huddleston (2002: 167) notes, while the simple present version

Admittedly, there is a tendency to equate habits with states, as evinced by Kearns’s (1991: 110) statement that “habituals are plausibly classed as a kind of stative.”16 Yet Brinton (1987) and Bertinetto (1994) argue convincingly that there are big discrepancies between the two.

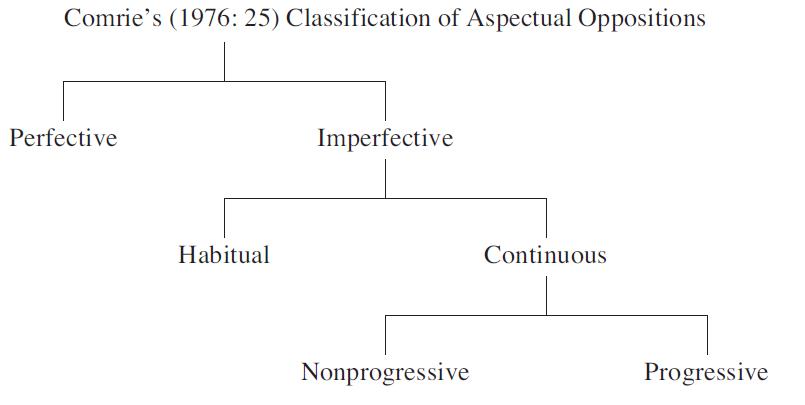

In this connection, it must be emphasized that the habitual is an aspect category rather than an Aktionsart category (Comrie 1976, Brinton 1987, 1988, Bertinetto 1994). In Comrie (1976: 25), for example, the habitual is analyzed as a subcategory of the imperfective aspect, as shown in Figure 1.

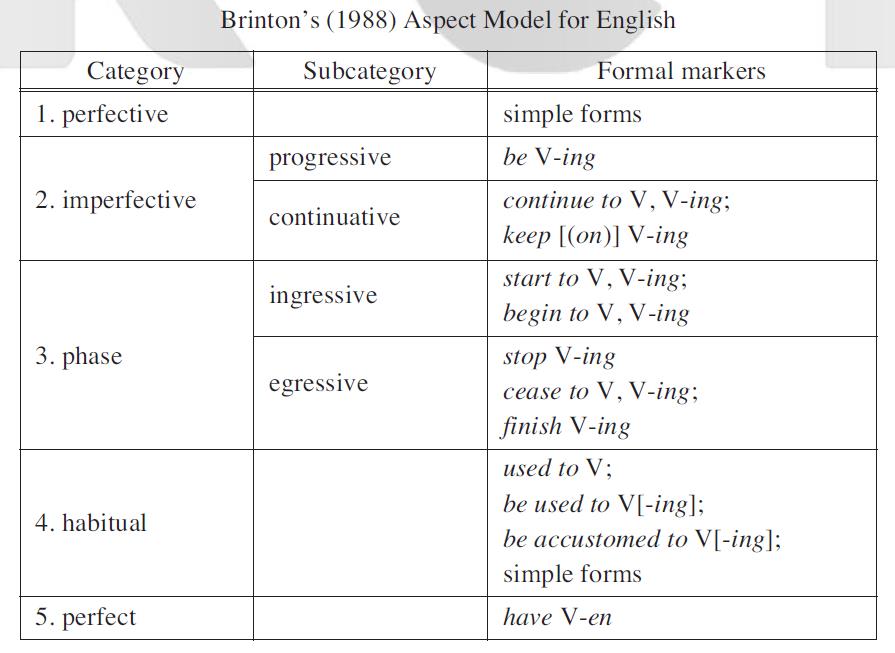

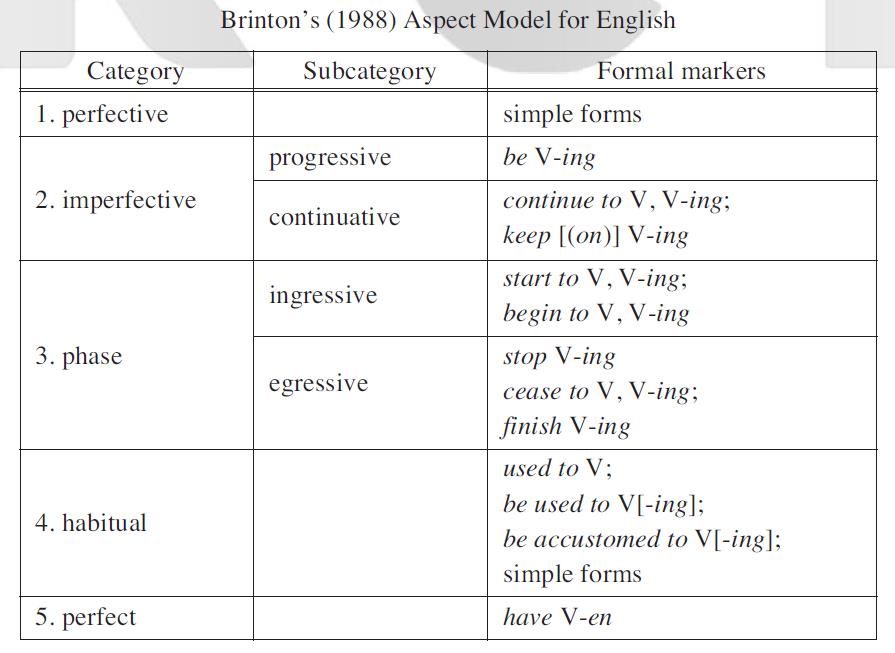

Brinton (1987: 209-10), on the other hand, argues that the habitual is probably a separate aspect category with a meaning different from that of the imperfective. Whereas the imperfective aspect views a situation as incomplete, the habitual aspect views a situation “as repeated on different occasions, as distributed over a period of time” (Brinton 1988: 53). Brinton’s (1988: 53) aspect model for English is presented in Table 3.

[Table 3] Brinton’s (1988) Aspect Model for English

Brinton’s (1988) Aspect Model for English

For the purposes of this study, it is not necessary to take a position about whether the habitual should be considered to be a subcategory of the imperfective or not. Suffice it to say that the habitual is an aspect, or way of viewing a situation. Given that the habitual is an aspect, it is natural that the habitual progressive is not an aspectual progressive because one cannot view a situation in two different ways.

Presumably one might refute this claim by saying that in the habitual progressive, “habits, which are not continuous, are represented as if continuous” (Brinton 1987: 209) and therefore it involves a sense of ongoingness. Yet the key point is that ongoingness is not a defining property of the habitual progressive but is only a contingent or subsidiary property. Again, the real essence of the habitual progressive is habituality. Hence there is a rationale for not treating the habitual progressive as a type of aspectual progressives.

Turning to the distributional constraints on the habitual progressive, there is not much discussion on this issue. Sag (1973: 85-87) proposes the so-called “progressive squish” arguing that the progressive futurate shows a more restricted distribution than the aspectual progressive (‘process progressive,’ in his terms), which in turn has tighter restrictions than the habitual progressive. We reserve this topic for future research.

14See the references cited in Brinton (1988: 41) 15Consequently, Huddleston (2002) treats (19) as an aspectual progressive. Indeed, in discussing non-aspectual uses of the progressive, Huddleston (2002: 171-72) does not mention progressives of this sort. 16Similar remarks are made by Vendler (1957/1967: 108), who notes that “[h]abits (in a broader sense including occupations, dispositions, abilities, and so forth) are also states in our sense.” Others use expressions such as ‘habitual state’ (Moens and Steedman 1988: 18) or ‘habitual stative’ (Smith 1997: 18, 50).

VI. The Experiential or Interpretative Progressive

Wright (1995: 156) employs the term ‘experiential progressive’ to refer to the progressive that focuses on “an experience, perception, observation from inside the speaker’s consciousness” rather than on an event in time. Such uses of the progressive have been described by Ljung (1980) as the ‘interpretative progressive.’17 Consider the following examples:

The progressives in (21) “signpost the speaker’s interpretation or evaluation of some state of affairs” and hence are subjectively construed (Wright 1995: 156). For example, in (21a), the speaker concludes from what his interlocutor has said that she does not love him anymore. The subjectivity of the speaker’s interpretation is quite obvious on the grounds that the interlocutor may explicitly cancel the implicature inferred by the speaker. Likewise, (21b) is subjective in the sense that the speaker has no access to the interlocutor’s mental processes.

While the experiential or interpretative progressive has been discussed in the linguistics literature, including Ljung (1980), Wright (1994, 1995), Smith (2002), and Killie (2004), to the best of our knowledge, it has not been covered in ESL/EFL grammar books. To understand the experiential or interpretative progressive better, let us consider examples like (21) from a corpus. Both (22) and (23) are taken from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA).18

In (22)-(23), the subjective function or meaning of the progressive is clear because the progressive construction provides an interpretation of the speaker’s perspective of the situation.

Notice that the experiential or interpretative progressive does not serve a primarily aspectual function. The meaning of ongoingness does “not belong to the content of the utterance but to the speaker’s progressively developing belief state” (Ziegeler 1999: 65). Furthermore, as Ljung (1980: 77) rightly points out, we would hardly answer (24) by saying (25), although we would answer it with non-interpretative progressives such as (26).19

17Alternative terms for the experiential or interpretative progressive include ‘emotive,’ ‘vivid,’ and ‘phenomenal’ progressive (Wright 1995: 156). 18The COCA is freely accessible online at http://corpus.byu.edu/coca/. In (22)-(23), more detailed source information is provided in parentheses after the semicolon. The numbers refer to the date and ‘FIC’ is an abbreviation of fiction. The title of (22) is Shrek the Third and (22) is drawn from ‘Final Screening Script 53,’ which is also found at http://www.joblo.com/scripts/script_shrekthethird.pdf. 19The examples in (24)-(26) are all drawn from Ljung (1980: 77). Admittedly, What’s John doing at the moment? sounds better than (24).

“To mistakenly describe the progressive as a tense” (Richards 1981: 399), as in some ESL/EFL grammar books, such as Azar (2002: 3), leads to a misunderstanding of progressive constructions in English. In order to encompass the fact that the English progressive is unusually wide in its range of uses, it is instructive to make a distinction between aspectual and non-aspectual progressives. The primary function of the progressive is to present a situation as ongoing, and this strictly aspectual use of the progressive is referred to as ‘aspectual progressive.’ On the other hand, the uses of the English progressive that are not, in a strict sense, aspectual is called ‘non-aspectual progressive.’20 In this paper, the term ‘progressive aspect’ is reserved for aspectual progressives only, while ‘progressive construction (

One can distinguish at least three basic uses of non-aspectual progressives. The first is the so-called progressive futurate (e.g.,

It is hoped that the findings from the present study are relevant for ESL/EFL textbook writers as well as linguists. The following passage suggests that in Biber et al. (1999), the term ‘progressive aspect’ is used in a broader sense, encompassing both the ‘aspectual progressive’ and the ‘progressive futurate’ in our terms.

However, as has been stressed in the preceding discussion, aspectual progressives should be distinguished from non-aspectual progressives.

20An advantage of the classification adopted in this paper is that the distributional constraints on English progressives (namely, the claim that state verbs and achievement verbs do not allow the progressive) applies to aspectual progressives only. Space considerations preclude a detailed discussion on the distribution of English aspectual progressives. For details, see Lee (2004).