In the past decade, the Korean film industry has enjoyed never-before-seen success at home and abroad. With the high domestic market share of local movies (recording more than 40% market share continuously from 2001), it has been reported that Korea is “the only nation during the post-Vietnam War history that would regain its domestic audiences after losing them to Hollywood”

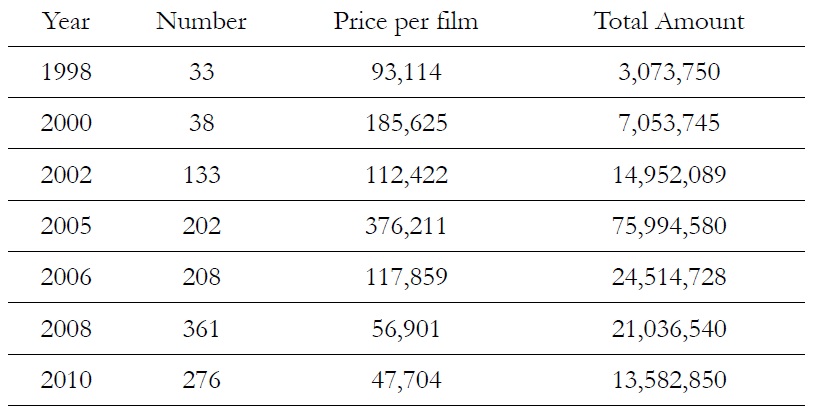

In the period circa 1999–2006, the Korean film industry enjoyed its never-beforeseen success both at home and abroad. With the high domestic market share of local movies (recording more than 50 percent market share continually from 2001), it was reported that Korea was “the only nation during the post-Vietnam War history that would regain its domestic audiences after losing them to Hollywood” (Kim K., “Movie Power.”).2 Based on this domestic achievement, the foreign export of Korean films drastically increased, from 14 movie exports for US$173,838 revenue in 1993 to 202 movies for over US$75 million in 2005. Some scholars interpreted this commercial achievement as a successful resistance against American cultural imperialism within the local vs. global paradigm.

If we naïvely stick to the above line of interpretation, we ignore the corporate concentration process in cultural production. Even Herbert Schiller (1992) revised his thesis of American cultural imperialism in the 1990s, arguing that the modern juggernaut in global culture was transnational corporations with U.S. know-how in production and marketing practices. As such, the issue today is not so much whether there is global or local control of the media, but how the implications of corporatization are manifested in cultural productions in each locale.

In fact, the Korean film industry has been through many upheavals and trials in the past two decades. Local big business conglomerates, or

Despite more critical raves from abroad, and more invites to the top international film festivals, those in the Korean film industry, ranging from filmmakers to critics, these days are surrounded by crisis-consciousness. In order to understand the discourse of the Korean film industry crisis, this study applies a multi-layered analysis with foci ranging from

2Except for 2002, when the figure was 48.30 percent.

In 2010, important directors whose films had been critically praised at home and abroad tasted the bitters in theaters. Lee Chang-dong’s

On the other hand,

3A street in Seoul, Chungmuro refers to the Korean film industry. Chungmuro used to host hundreds of film production-related companies in the period of 1950s and 1990s, although many film companies have since moved to the Kangnam area in Seoul.

Up until the early 1990s the average Korean film cost less than a million dollars. Film producers were satisfied with “low risk, OK return” projects like romance stories and adult films instead of venturing on epic films. One of the reasons leading to this situation was that their films were financed, not by banks, but by film distributors and usurers who lent money at excessive rates of interest on a short-term loan, around three to five months, so that filmmakers had to make puny films within a short period of time.

The Asian economic crisis in 1997 worked favorably for some Korean film companies. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) ordered sprawling

This propitious condition promoted young, aspiring filmmakers’ debuts with ease. Between 1996 and 2000, modern Korean cinema’s most important directors including Kang Je-gyu, Kim Ki-duk, Lee Chang-dong, Bong Joon-ho, Hong Sangsoo and Kim Jee-woon released their first films. This new generation of filmmakers produced creative potential that had not existed in the local scene. The Asian economic crisis further created favorable conditions for film business. As millions of people lost jobs, they wanted to forget their predicament and have fun by going to the cinema. In addition, as the local people called the crisis an “IMF Crisis,” anti-foreign sentiments were formed, and they ardently supported homegrown goods and services including movies (Shim, “South Korean.”). Therefore, when Kang Je-gyu’s

From

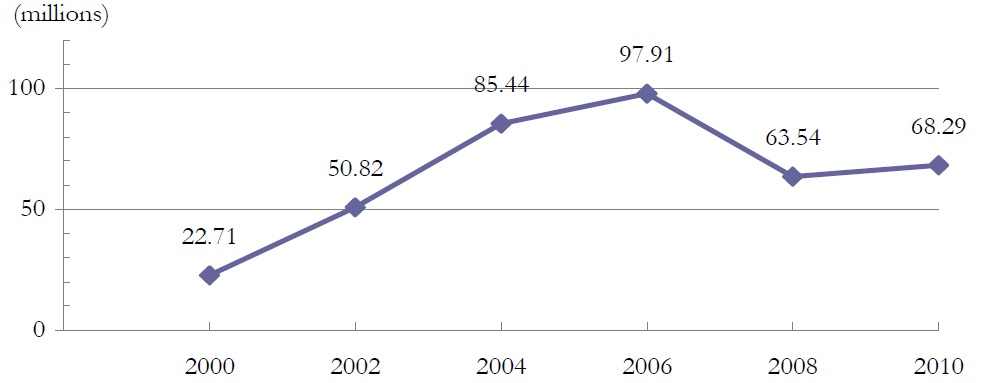

The trend of yearly appearing record-setting films has not, however, continued since 2007, although

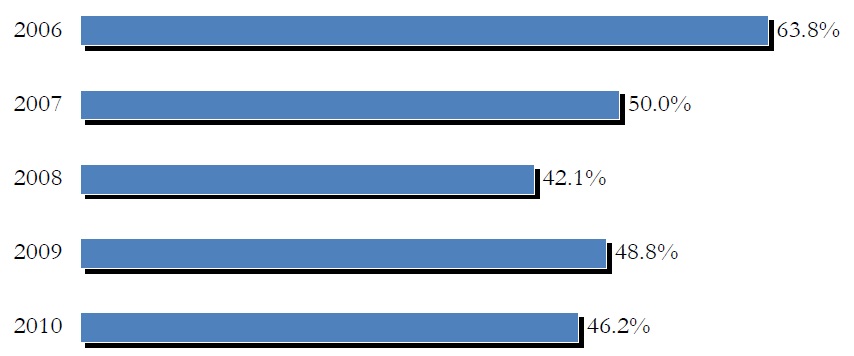

In the same vein, the local market share of Korean films also dropped to 42.1 percent in 2008, after hitting 63.8 percent in 2006 (see Graph 2 below).

In a sense, the bubble in the early and mid 2000s spoilt the film industry, before it fizzled. At that time, a lot of foreign investors were willing to gamble very much on the local entertainment industries. Accordingly, many film projects began to focus on international financing, casting big-name actors, not using solid storytelling (see Graph 3 below).

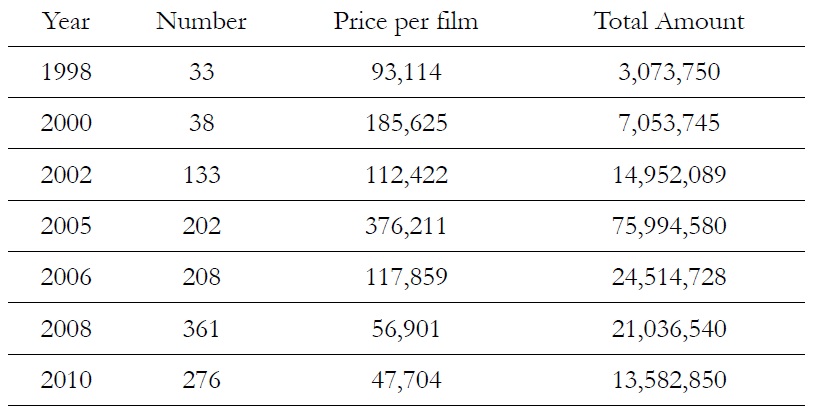

Gradually, investors and distributors had the final say, and Korean films were made, not by directors but by number crunchers. We also need to pay attention to the “backdoor listings” boom. In the early and mid 2000s, many film production and distribution companies went public, although they did not have solid financial foundations. In fact, they teamed up with more stable partners, such as high-tech companies and manufacturers, and cranked out movies to improve their bottom line. When the owners raised money and the share prices ran into trouble, some of them skipped town taking all the money with them. This explains the fact that Korean theaters were flooded by many terrible and messy movies in the mid 2000s. A glut of mediocre and poor movies eventually deflected audiences, investors and importers away from Korean films. In the end, from 2006 the exports took a nosedive (see Table 1 below).

[Table 1.] Korean Film Export Amount (in USD)

Korean Film Export Amount (in USD)

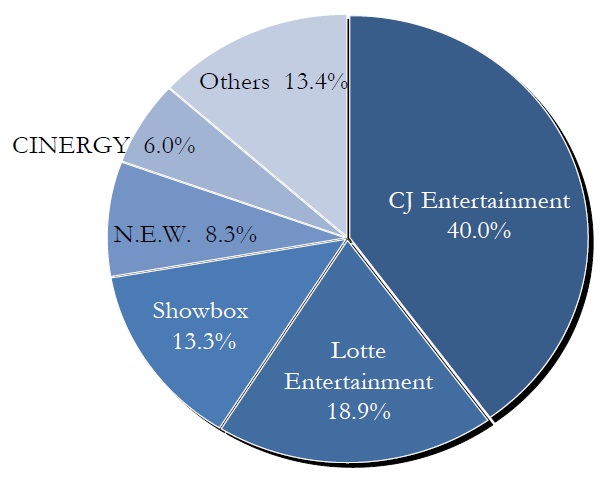

An industrial restructuring took place in this period. As noted, the Asian economic crisis in the late 1990s turned out to be a significant boon for the remaining film companies. In the early 2000s, Cinema Service, founded on traditional Chungmuro manpower and capital, and CJ Entertainment, a late-comer in the 1990s, ruled local film distribution. Then, from the mid-2000s, telcos expanded into the film industry in order to find synergy between content and pipe. For example, Korea Telecom (KT) and SK Telecom saw film production companies as supply lines for their smart phone, Internet Protocol television (IPTV), and digital mobile broadcasting (DMB) businesses. Telcos’ expansion was, however, stalled as they found film business too risky. Since 2007, an oligopoly comprising three majors including CJ Entertainment, Lotte Entertainment, and Showbox/Mediaplex has secured the command of distribution (see Graph 4 below).

CJ’s and Lotte’s distribution power is based on their grip on exhibition. As of 2011, CJ Entertainment’s multiplex franchise, CJ CGV, is the largest theater chain in Korea, with around 40 percent of the nation’s 2,000-plus screens. Lotte Entertainment’s franchise Lotte Cinema chain comes second, with around 25 percent of the nation’s screens. From around 2009, CJ and Lotte have become more vertically integrated, by expanding into film productions, much to the consternation of the small and mid-sized production companies. Yi Yu-jin, CEO of Jip Film, points out the implication of this concentration:

Producers also point out the problems in profit distribution ratio currently practiced in the Korean film industry. The scheme is being enforced in the following way. Firstly, proceeds from ticket sales are divided evenly between exhibitors and investors/distributors. Secondly, when a movie goes over the break-even point, investors/distributors share their portion of profits with production companies by the ratio of six to four. On the other hand, if a movie does not reach the break-even point, the ratio is reset to eight to two in further favor of investors/distributors (Ji, “Interview with Kim.”). As such, currently when just around 10 percent of all Korean movies released exceed the break-even point, those small and mid-sized producers have difficulty surviving. On the other hand, considering that the major distributors control investment and exhibition, they have nothing to lose in this game.

While many filmmakers worry that the majors would use their leverage to bully the rest of the industry, different views exist (Kim Hyeon-min, “Interview with Jo.”). According to Kang Hye-jeong, CEO of Oeyunaegang Film,

Kang, however, feels sorry for the situation in which the pre-existing, delicate balance between producers, investors, distributors, and exhibitors has collapsed in favor of vertically integrated majors. Kim Mi-hi, a veteran producer who is also a CEO of Studio Dream Capture put it: “When two Korean films topped one million admissions in 1996, everyone in the industry was excited. However, when they knew that 5 million, or even 10 million, were possible, Korean filmmakers were not satisfied with modest hits, and focused on money-making” (Ji, “Interview with Kim.”). Going through this trajectory, she regrets that solid stories are rarely found in the movie world.

In this section, we shall discuss two factors (poor rewarding of screenwriters and a unique audience culture) that would lead to the thriller genre dominance in Korean theaters. As noted, one of the reasons for Korean film to have come this far was the rise of a new, creative generation of filmmakers. However, those screenwriters-turned-directors including Kang Je-gyu, Park Chan-wook, Yoon Je-gyun, Lee Chang-dong and Bong Joon-ho are still writing for their own film projects (Kim Hyeon-min, “Interview with Jo.”). It is because of a scant supply of quality screenplays in the market. In this vein, director Park Chan-wook says that “it is my sincere wish to get behind a camera with a screenplay written by others” (“Sisa Gihoek.”). There are in fact many young, aspiring screenwriters in Korea. However, after finding that writers are poorly rewarded in the film industry, they would leave for the television industry (Ji, “Interview with Kim.”). This situation of scant quality screenplays partly explains the recent trend of Japanese manga adaptation for Korean films.

That the cinema-goers in Korea are largely comprised of daters in their twenties and early thirties is worthy of attention. As the main aim of their cinema-going is to kill time and have fun, they tend to shun serious movies, genre films, and those displaying aesthetic challenges. Instead, they would rather watch thriller films. These two factors (poor rewarding of screenwriters and a unique audience culture) are associated with the profit-making structure of the Korean film industry. As is different from the U.S. film industry, of which revenue sources are evenly divided between theatrical releases and the secondary market, 80 percent of the revenues of the Korean film industry come from theaters. Therefore, whether a Korean film is successful or not is decided in theaters. Further, as is different from the heyday of Korean film in the early 2000s, fewer numbers of movies break even these days, leading to the scale of film investment diminishing. In this situation, filmmakers tend to follow a recipe for success, depending on popular genres like thriller, and casting big-name actors and getting famous directors. In this process, other elements in film production are neglected, and film companies cannot afford to pay the screenwriters adequately.

According to director Jang Hang-joon, seven of his film projects folded in the past several years because he could not secure enough investment, without all-star casts in his films. He adds that the Korean film industry is morphing into an enterprise in which only a small number of directors and actors prospers (“Sisa Gihoek.”). According to Moon Seong-ju, head of the investment division at Cidus FNH Film, the best way to break this vicious cycle of stalled or decreasing profitability and trimming production costs is to develop the secondary market. He argues that the government should develop stronger measures to protect copyrighted materials, and widespread illegal downloading should be stopped (Jang, “Interview with Moon.”).

In this paper, we have examined various reasons behind the commercial film genres and styles being dominant in the current Korean film industry, with a focus on implications from vertical integration and concentration.

As of 2011, Korean filmmakers are making every effort to expand abroad. But, this time their strategy is different from that of a decade ago when collaborations and co-productions with Japan and China were the norm. Its reasoning was as follows: By producing something which was both “Chinese” and “Korean,” the target audience would immediately increase. According to Park Deok-ho, head of the international business center at the Korea Film Council, such sanitized projects, however, did not attract either of the two intended national audiences (Ji, “Interview with Park.”). After experiencing many failures from co-productions with Japan and China, Korean filmmakers now try bolder projects. For example, Yoon Je-gyun is currently working on a film,

The thriller trend noted above can also be understood in that that genre tends to succeed in global markets. Action and suspense being universal, the thriller genre has a lower rate of cultural discount than has drama or comedy. In fact, Park Chan-wook’s thriller

As well, the Korean film industry needs to find a lesson from the Hong Kong film industry, which used to be an Asian film powerhouse. Its annual film production in recent years is just around 50, a major nosedive from around 300 films in its heyday in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Hong Kong’s domestic film market share dropped from around 70 percent to 30 percent during this transitional period. Critics and popular opinion uniformly pronounce that the Hong Kong film industry was caught in its own trap; endlessly casting the same stars in similar films eventually drove away audiences.

The screen quota system has contributed to the growth of Korean film, by forcing local theaters to screen Korean movies for 146 days per year, helping to increase the range and diversity of Korean films. In 2006, however, the Korean government decided to reduce the screen quotas to 73 days as a precondition for negotiations on the free trade agreement with the United States (Shim, “The growth,” 31). Korean film, more than 80 percent of profits for which come from theaters, is now desperate to diversify its profit sources. In particular, the rampant illegal downloading of movie files has virtually destroyed the DVD and rental markets. According to the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, as of 2009 the amount of damage from illegal downloading was rated at 508.9 billion Korean won while the size of the legal film market was 1.5 trillion Korean won.4 The good news is that the National Assembly passed a bill in April 2011 to force web hard disk companies to register with the Korea Communications Commission (Min, “Stop on illegal.”). By this, it is expected that the government authorities are going to aggressively crack down on online communities that share illegal movie files.

About a decade ago, scholars, filmmakers and journalists alike praised the growing trend toward transparency and openness with respect to high-risk, high-return entrepreneurialism in the Korean film industry (Segers; Shim, “South Korean.”). This line of appraisal still may be valid, in that big business is the means of stable cash flow (Han, “Interview with Kim.”). In recent years, however, more people worry that this entrepreneurial environment alone does not make films (Kim Hyeon-min, “Interview with Jo.”). It needs talented filmmakers, solid screenplays, and the principle of diversity to push the industry to the next level. Again, no-one knows what Korea’s film industry will look like a decade later.

4US$1 is rated around 1,100 Korean won as of 2011.