This study identifies reasons why North Korea initiates conflicts against South Korea and its allies, and also provides suggestions to deter North Korea’s future provocations. Logistic models with robust standard errors indicate North Korea is likely to adopt hostile foreign policies when it is prior to and following leadership succession and when the United States is involved in a war. Moreover, while the effects of economic factors on North Korea’s or North Korean conflict behavior vary, they become more significant when interacting with both North Korea’s leadership succession and US preoccupation with other world affairs. The findings suggest the following: First, that South Korea should pay extra attention to North Korea when it pursues leadership succession. Second, in addition to solidifying the existing Korea-US military alliance, South Korea should build self-sufficient defense forces for a scenario in which the United States would be unable to provide a security umbrella. To deter North Korea’s repetitive attacks in this context, South Korea primarily needs to change its military doctrine from the ‘deterrence by denial’ to a ‘proactive deterrence strategy.’ Moreover, stealth and C4ISRPGM capabilities are necessary to execute this strategy. Third, South Korea and international societies should help North Korea change its economic infrastructure instead of providing direct humanitarian aid.

The tragic sinking of the Republic of Korea Ship (ROKS) Patrol Combat Corvette Cheonan (PCC-772), which occurred near the Northern Limit Line (NLL) of the Yellow Sea on 26 March 2010, caused forty-six casualties. Subsequently, international cooperative efforts were undertaken in a bid to identify the causes of the sinking of South Korea’s Navy warship. The Joint Civilian-Military Investigation Group (JIG) found that the corvette was demolished by a clandestine North Korean torpedo attack.1) Despite allegations that the JIG’s explanations were false, the majority of South Koreans and international society agree that the tragedy was inflicted by a North Korean torpedo attack. Later that year, North Korea boldly shelled South Korea’s Yeonpyeong Island (23 November 2010), killing two marines and two civilians. Since this incident, the tensions between the two Koreas have been high.

Given this context, why has North Korea threatened and sometimes attacked militarily South Korea and its allies knowing that such behavior leads to insurmountable repercussions from them? Do North Korea’s repetitive attacks against South Korea necessitate a revision of South Korea’s defense policy that mainly focuses on a ‘defense by denial’ approach? If so, what political solutions or military options would deter North Korea’s further antagonistic behavior? In essence, how can South Korea nullify North Korea’s unpredictable strategy?

To answer these questions, I employ three main theories to explain why North Korea has imprudently initiated militarized disputes with and actions against South Korea and its allies, and I empirically test these arguments by using the Correlates of War data (1960-2001). Logistic models with robust standard errors signify that North Korea’s imprudent militarized disputes against other countries are most likely to occur when North Korea prepares for leadership succession. More interestingly, the effect of North Korea’s economic conditions becomes significant when it interacts with both the level of US preoccupation with other commitments and the leadership succession.

Scholars have provided diverse explanations as to why North Korea has challenged seemingly undefeatable foes (e.g., South Korea and its allies). However, many fail to employ rigorous tests to verify whether or not their theoretical arguments are empirically supported. They also neglect to make a clear concatenation between their theories and policy suggestions aiming to deter North Korea’s idiosyncratic foreign policies. Thus, this study attempts to fill those gaps in the existing literature by offering both theories supported by empirical results and realistic policy suggestions so that policymakers will be able to devise relevant military doctrines and strategies to deter antagonistic actions by North Korea in the future.

In the next section, I first briefly discuss three main contextual reasons why North Korea is more likely to embark on militarized disputes and draw four testable hypotheses based on these theoretical explanations. Second, I test the hypotheses by using appropriate statistical method and analyze coefficients and discuss their political implications. Third, I discuss how South Korea should respond to identified causes of North Korea’s conflict behavior. Finally, I conclude by suggesting a proper military strategy for South Korea’s military in order for it to adapt to unpredictable political environments in the post-9/11 world.

1)Ministry of National Defense Republic of Korea, “Investigation Result on the Sinking of ROKS ‘Cheonan’,” Ministry of National Defense Republic of Korea (20 May 2010), available at

Since the Korean War, scholars have described the relations between the two Koreas as an enduring rivalry or a strategic rivalry because of the long history of repeated conflict and psychologically atypical hostility toward each other.2) According to the Correlates of War data set, North Korea initiated militarized interstate disputes against South Korea twenty-three times between 1954 and 2001. It also caused similar conflict against Japan four times between 1997 and 2001. More importantly, North Korea has launched numerous conflictual policies against South Korea, the United States, and other countries since 2002. Why has North Korea maintained hostile foreign policies against South Korea and its allies knowing that their behavior is more likely to result in negative consequences?

In order to answer this question, I concentrate on three main theoretic arguments: the diversionary theory of war, the selectorate theory, and the window of opportunity theory. First, the diversionary theory of war argues leaders of countries that have domestic political problems are more likely to attack other countries in order to divert people’s attention.3) At the same time they are able to create a “rally ‘round the flag” effect that enables them to increase their chances of political survival (i.e., winning reelection). In other words, if leaders are politically vulnerable at home, then they are more likely to show international bellicosity or foreign aggressiveness. For instance, Lebow finds that during the Falklands War, the leader of Argentina suffered from domestic pressure driven by devastating economic crises and large-scale civil unrest against the military junta.4) On 2 April 1982, the Argentine military government, headed by General Leopoldo Galtieri, sought to maintain power by invading the Falkland Islands, which was UK territory, with a view to diverting public attention.

In line with the diversionary theory of war, it is plausible that North Korea is also likely to adopt foreign adventurism, such as military attack against South Korea and its allies, when it suffers from economic recession. For instance, Cho claims North Korea’s failed currency reform is one of the main factors that led to the ROKS Cheonan incident.5) Because North Korean leader Kim Jong Il had to face the high probability of protest from the public, he allegedly ordered the torpedo attack on South Korea’s warship as well as an overt military attack on South Korea’s territory to induce a rally-aroundthe-flag effect.

In a similar vein, although North Korea had been able to compete economically with South Korea until the 1970s, North Korea’s GDP percapita declined approximately 25 percent from 1990-2002. The mid-1990s food shortages due to severe flooding drastically undermined the North Korean economy. With the deterioration of its economy, North Korea felt more insecure against international pressure. It secretly started a nuclear development program to increase its bargaining power.6) These two examples clearly show that North Korea’s economy has been a main factor resulting in its conflict behavior. Based on this theoretical explanation, the first testable hypothesis is as follows.

Second, Bueno de Mesquita, Morrow, Siverson, and Smith posit that leaders only care about their political survival.7) Hence, leaders sometimes reason that waging a war against selected easy targets can be an intriguing option for hem to extend their political fortune.

Distinct from other communist regimes, leadership change by election or some other institutional means has not occurred in North Korea since the Korean War. It has been acceded within Kim’s family. In addition, the people in North Korea have been influenced by the Confucian traditions and government propaganda, making it forbidden for them to challenge their “father-like” leader. In light of its leadership change, therefore, it should be categorized as a monarchical system, in which heirs are supposed to inherit power from their father. On account of this peculiar political context in North Korea, I assume that the main interest of North Korea’s leader is protecting the status quo, and that is why Kim Jong Il tended to focus only on exploiting the existing political environment to augment his leadership.

Kim Jong Il should have catered to the members of the winning coalition by providing private goods in order to achieve successful power succession to his son, Kim Jong Un. In line with Kim Jong Il’s intention, high-ranking military officers also support the leadership succession in Kim’s family because they think that it is the most secure way to extend their political survivability. As a result, it is more likely that North Korean leaders and their military supporters consider North Korea’s leadership succession as the means of extending their political survival. Besides, when they perceive challenges from other potential political contenders in the winning coalition as well as protests from domestic opposition groups or from the public, they are more likely to employ risky foreign policies such as developing a nuclear program, testing long-range missiles, and so forth to collectively subdue contenders and a restive public.

In a similar vein, North Korea’s most recent successor, Kim Jong Un, is also eager to show off his capability as a leader. Moreover, he does not have to contend with domestic rivals to consolidate his status as there appear none. He is solely able to channel his attention to building his career by undertaking foreign adventurism, such as attacking South Korea’s warships, marines, and civilians. In this way he can keep at bay the likelihood of negative sentiments among power elites or uprisings from opposition groups in North Korea.

Furthermore, even if an heir successfully ascends to the throne, it is premature to conclude that he completely controls his regime. As a result, the new and inexperienced heir is more likely to resort to existing domestic and foreign policies utilized by his father (e.g., in the case of North Korea, military-first policy, Juche ideology, sensitive nuclear material exports, nuclear and missile tests, military provocations against South Korea, and so forth). All other things being equal, North Korea’s hostile foreign policies against South Korea and its allies are more likely to occur in the leadership succession period as well as at the beginning of its new leadership. This theory leads to the second hypothesis.

Third, Kim argues the reason why North Korea attacked South Korea and has challenged the United States is because of the US preoccupation with two ongoing wars.8) Kim argues conflicts between a hegemonic country and weak states occur due to bargaining failures, which are a function of asymmetric information between states.9) Therefore, when a hegemonic country is involved in a war, there is a window of opportunity for other states to act aggressively. Given this context, North Korea is inclined to adopt hawkish foreign policies against the United States and South Korea because the U.S. preoccupation with the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq makes North Korea believe that the United States does not retain sufficient military capabilities and resolves to sustain its existing punishment strategy against its new challengers. North Korea interprets the US ambivalent situation as a window of opportunity for it to challenge its international status quo. In other words, North Korea (as well as Iran) strives to exploit the condition under which the United States is not able to intervene into other states to achieve its political objectives. This situation ultimately disables the existing deterrence mechanism between North Korea and the United States and its allies. As a result, North Korea is more likely to attack South Korea in this context. The testable hypothesis derived from this theoretical argument is as follows.

Lastly, as Clauzewitz postulates, war is a continuation of politics by other means.10) The outcome of war is so unpredictable because it is the sum of decisions, actions, and reactions in an uncertain, dangerous context. In other words, the decision to go to war is a consummation of lengthy and complex calculations among key national decision-makers due to its uncertainty. Therefore, even though one of the three aforementioned factors has an independent impact on the likelihood of North Korea’s conflict behavior, the relationship tends to be modified by the multiplicative effects of other variables. For example, even if Kim Jong Il and his regime is in an economically difficult situation, it may not be a sufficient and necessary condition for him to initiate a war against other states. In other words, he is sometimes reluctant to wage a war if he can anticipate the ex post inefficiency of militarized provocation against South Korea, Japan, and the United States in advance. However, if he undergoes two or three aforementioned factors at the same time, this situation is prone to encourage him to accept risk derived from undertaking militarized disputes or attacks against those states. Based on this reasoning, the fourth hypothesis is as follows.

2)Scott D. Bennett, “Integrating and Testing Models of Rivalry Duration,” American Journal of Political Science 42-4 (1998), pp. 1200-1232; William R. Thompson, “Identifying Rivals and Rivalries in World Politics,” International Studies Quarterly 45-4 (2001), pp. 557-586. 3)Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, J. D. Morrow, R. M. Siverson, and A. Smith, “An Institutional Explanation of the Democratic Peace,” American Political Science Review 93-4 (1999), pp. 791-807; Patrick James and John O’Neal, “The Influence of Domestic and International Politics on the President’s Use of Force,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 35-2 (1991), pp. 307-333; Sara McLaughlin Mitchell and Will H. Moore, “Presidential Use of Force During the Cold War: Aggregation, Truncation, and Temporal Dynamics,” American Journal of Political Science 46-2 (2002), pp. 438-452; Sara McLaughlin Mitchell and Brandon C. Prins, “Beyond Territorial Contiguity: Issues at Stake in Democratic Militarized Interstate Disputes,” International Studies Quarterly 43 (1999), pp. 169-183; T. Clifton Morgan and Kenneth N. Bickers, “Domestic Discontent and the External Use of Force,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 36-1 (1992), pp. 25-52. 4)Richard Ned Lebow, “Miscalculation in the South Atlantic: The Origins of the Falklands War,” in R. Jervis, N. Lebow, and J. Stein (eds.), Psychology and Deterrence (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985), pp. 89-124. 5)Bong Hyun Cho, “Pukhan-eui 5 Cha Hwapye Gaehyeog: Jindan-goa Jeonmang” [Monetary Reform in North Korea: Diagnosis and Prospect], Kukbang Yeonku [Defense Study] 53-2 (2010), pp. 137-167. See also Kyung-Young Chung, “Cheondanham Satae-oa Hankun-eui Anbotaese” [The Sinking of the Cheonan Warship and National Security of the Republic of Korea], Kunsa Nondan [Military Forum] 62 (Summer 2010), pp. 87-111; “North Korea ‘Panic’ after Surprise Currency Reevaluation,” Associated Press (3 December 2009), available at

To test the aforementioned hypotheses, I created a country-year dataset. Because of difficulties in North Korea’s data accessibility, the temporal domain for this research is from 1960 to 2001.11) The unit of analysis is annual observations. I employ a dichotomous dependent variable,

The Likelihood of North Korea’s MID Initiation: This dependent variable is used to capture the concept of North Korea’s military challenges against South Korea and its allies. Initiation of MIDs by North Korea means that North Korea initiates any type of militarily hostile action (e.g., threat to use force, display use of force, use of force, and war) toward South Korea and its allies. To operationalize this concept, I employ the MID 3.1 dataset (Side A: Initiators of Militarized Interstate Disputes). According to Ghosn and Palmer, “the overall ‘Side A’ variable marks which states were on the initiating side in the overall dispute, that is, states on the same side as the state who took the first militarized action.” As a result, “this marker identifies which state in the dyad took the first militarized action against the other state in the dyad.”12) Based on the MID 3.1 data, I code this variable as a ‘1’ if North Korea initiated a MID in a given year. Otherwise, I code it as a zero.

1) North Korea’s Economic Recession: I use North Korea’s economic data to test a diversionary theory hypothesis. First, North Korea’s annual economic growth rate is employed to test how annual changes in North Korea’s economic growth have influenced its conflict behavior. The data for this variable is derived from the Penn World dataset (1972-2001). To calculate annual changes in North Korea’s economic growth rate, I subtract T- 1 year’s economic growth rate from T year’s value. I expect when North Korea suffers from negative economic growth rate, it is more likely to initiate military conflict against South Korea and its allies.

Second, I use the World Bank’s annual

2) North Korea’s Leadership Succession: To test the second hypothesis, I operationalize the concept of North Korea’s leadership succession. Due to the limitation of available data, the temporal domain is from 1960 to 2001. There is only one leadership succession from Kim Il Sung to Kim Jong Il.

Kim Il Sung designated Kim Jong Il as his successor in 1974 at the 8th Plenum of the Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea. However, being a successor does not mean that he is able to wield his power to initiate military conflicts against other states. Moreover, if a successor has domestic challengers, he may not be able to seek foreign adventurism. Instead, he needs to focus on the political ploys that enable him to protect himself from potential challenges. Distinct from existing approaches, therefore, I assume that the year of 1989 is the first year that Kim Jong Il became a sole successor because his last rival, Kim Pyong Il, left North Korea for Hungary in 1988.14) After this year, he was able to control North Korea’s National Defense Commission (NDC). He became the first Deputy Chairman of the NDC in 1990. At last, he assumed the role of the Chairman of the much elevated and expanded NDC in 1993.15) These historical phenomena suggest that, as far back as 1989, Kim Jong Il became a real successor who could threaten South Korea and other countries. Thus, I code this variable as a ‘1’ between 1989 and 1994, the latter year being the year that Kim Il Sung died.

Additionally, my theory also suggests that a new and callow heir is more likely to be hawkish because he generally follows what his father had adopted to maintain his power until he can independently control his regime. As a result, I add five more years (1995-1999) to the period of leadership succession preparation. As a result, I code the years between 1989 and 1999 as a one, and zero otherwise. I expect that North Korea is more likely to initiate militarized interstate disputes in its regime succession and stabilization period.

3) US-War Involvement (USWI): This variable captures the concept of North Korea’s window of opportunity when the United States is preoccupied. Militarized Interstate Dispute data is used to operationalize this concept. To test my hypothesis, I create a

4) Three-Way Interaction Term (Economic Recession * Leadership Change * US War Involvement): Following my theory, one of the abovementioned variables alone may not be able to fully explain why North Korea has frequently provoked conflict with South Korea and its allies. Instead, I argue the combination of North Korea’s economic recession, its leadership succession, and the U.S.’s preoccupation with wars allows North Korea to challenge South Korea, Japan, and the hegemonic country’s status quo. Therefore, to operationalize this concept, I create a three-way interaction term (

I include control variables to avoid omitted variable bias. More importantly, I would like to check whether or not my theory holds controlling for all possible alternative explanations. First, a

Second, according to the strategic conflict avoidance theory,19) North Korea is less likely to initiate MIDs when the United States suffers from economic downturn. Because US leaders are more likely to adopt hawkish policies in order to divert their people’s attention and boost their popularity by winning the war, North Korea tries to avoid being a target in this context. US GDP is used as a variable that measures the effect of North Korea’s strategic conflict avoidance behavior on the dependent variable. I expect US GDP is negatively associated with the likelihood of North Korea’s MIDs initiation.

Third, scholars assert that states that form alliances with the hegemonic state tend to avoid alliances with states ignored by the hegemon because they do not share international preferences.20) Conversely, if they share similar international preferences and are satisfied with the hegemon’s status quo, they are less likely to go to war.21) To operationalize this concept, Signorino and Reiter’s Alliance Portfolio Similarity score (S scores) is used to measure the level of North Korea’s satisfaction with the U.S. international status quo.22) It ranges from -1 to +1, and it represents totally opposite alliance agreements to complete agreement in the alliances formed. I expect a negative relationship between institutional similarity and North Korea’s MID initiation.

Lastly, following the argument of arms race theorists,23) North Korea’s capability is employed to test whether or not North Korea’s strong military capability encourages it to initiate militarized interstate disputes against South Korea and its allies. I expect there is a positive relationship between North Korea’s military capability and its likelihood of initiating militarized interstate disputes.

The dependent variable for this research is a dichotomous one (the likelihood of North Korea’s MID Initiation). I employ the logistic model with robust standard error and estimate the following model:

11)The data for this research does not include current years. However, the analysis will provide crucial political implications that decision-makers in South Korea and its allies are able to utilize because this period also contains North Korea’s leadership succession period as well as all other necessary components. 12)Faten Ghosn, Glenn Palmer, and Stuart Bremer, “The MID3 Data Set, 1993-2001: Procedures, Coding Rules, and Description,” Conflict Management and Peace Science 21 (2004), pp. 133-154. 13)According to the World Bank data, the crop index is calculated based on the method considering the amount of crop production between 1999 and 2001 as 100. 14)So-hyun Kim, “Heir’s Brother Opposes N.K. Succession,” Korea Herald (13 October 2010), available at

I aim to identify the conditions under which North Korea initiates militarized interstate disputes against South Korea and its allies. Although the data for this analysis covers only from 1960 to 2001, the findings will provide crucial insights with regard to the real reasons North Korea has initiated military provocations as well as how to deter them in the future.

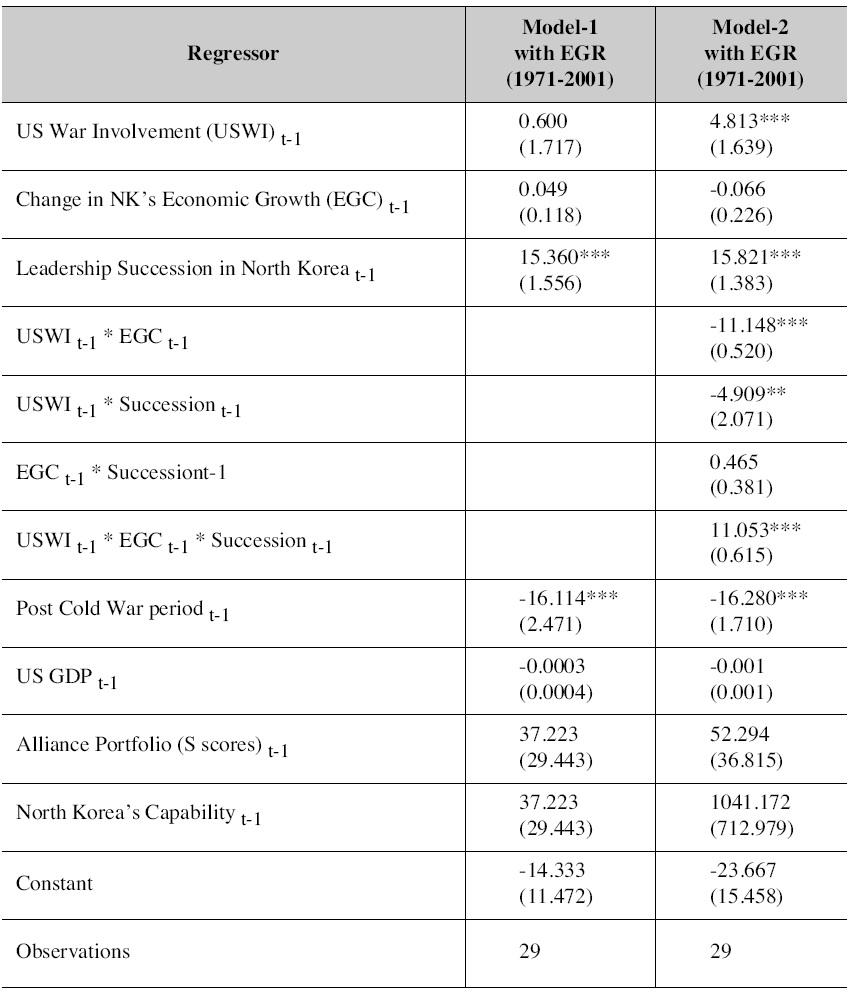

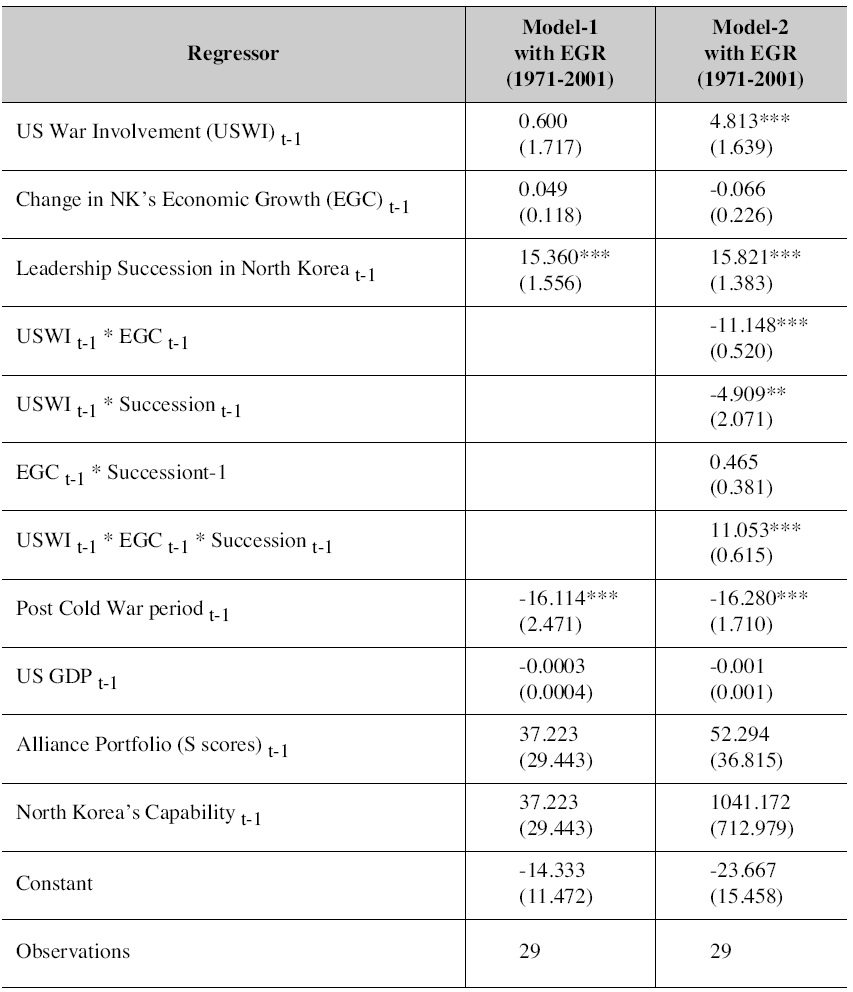

Table 1 presents the parameter estimates with robust standard errors. First, I check whether each main variable has an independent impact on the likelihood of North Korea’s MID initiation. I also test whether or not there are statistically significant multiplicative effects on the dependent variable. To be specific, Model-1 in Table 1 includes all independent variables and control variables. Additionally, I include a three-way interaction term in Model-2 to test all hypotheses controlling for all other variables.

The results in Model 1 only comport with the second hypothesis while Hypotheses 1 and 3 are not supported by them. They signify that North

[Table 1.] Logit Analysis of North Korea’s Conflict Behavior (with Economic Growth Rate)

Logit Analysis of North Korea’s Conflict Behavior (with Economic Growth Rate)

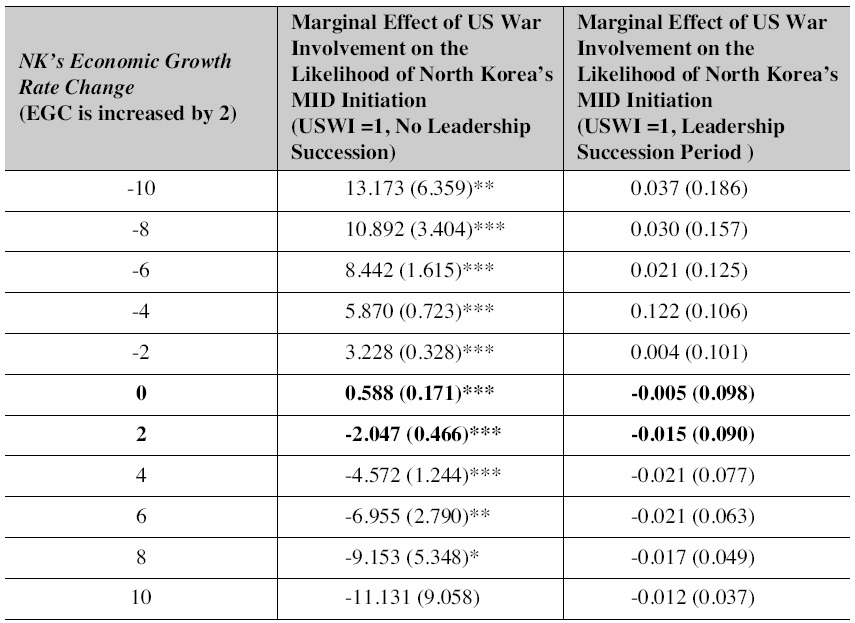

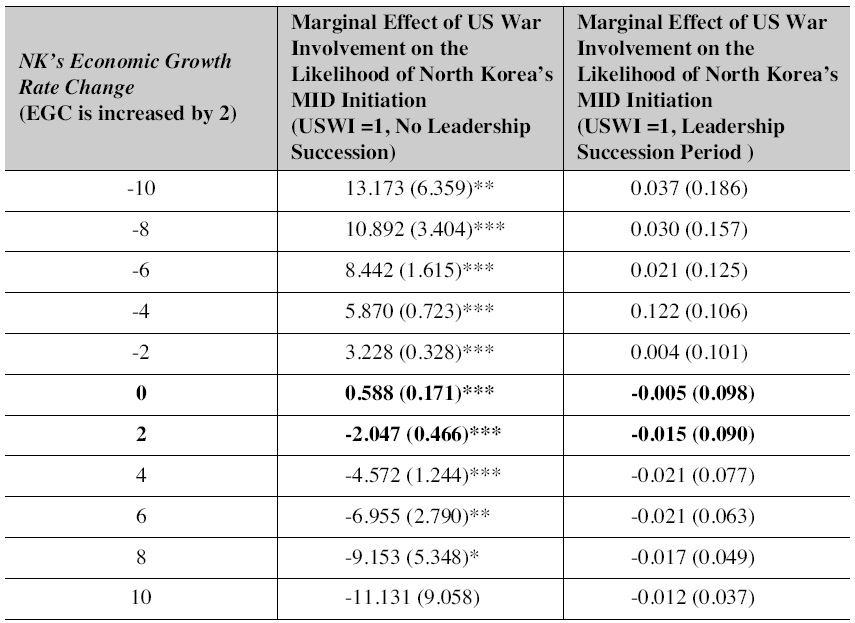

Three-way Interaction - Marginal Effect of US War Involvement on the Likelihood of North Korea’s MID Initiation as Economic Growth Rate and Leadership Succession Change

The coefficients of interaction terms, however, do not convey anything unless we address the problems in standard errors of coefficients (

As can be seen in Table 2, when North Korea does not pursue its leadership succession, the effect of

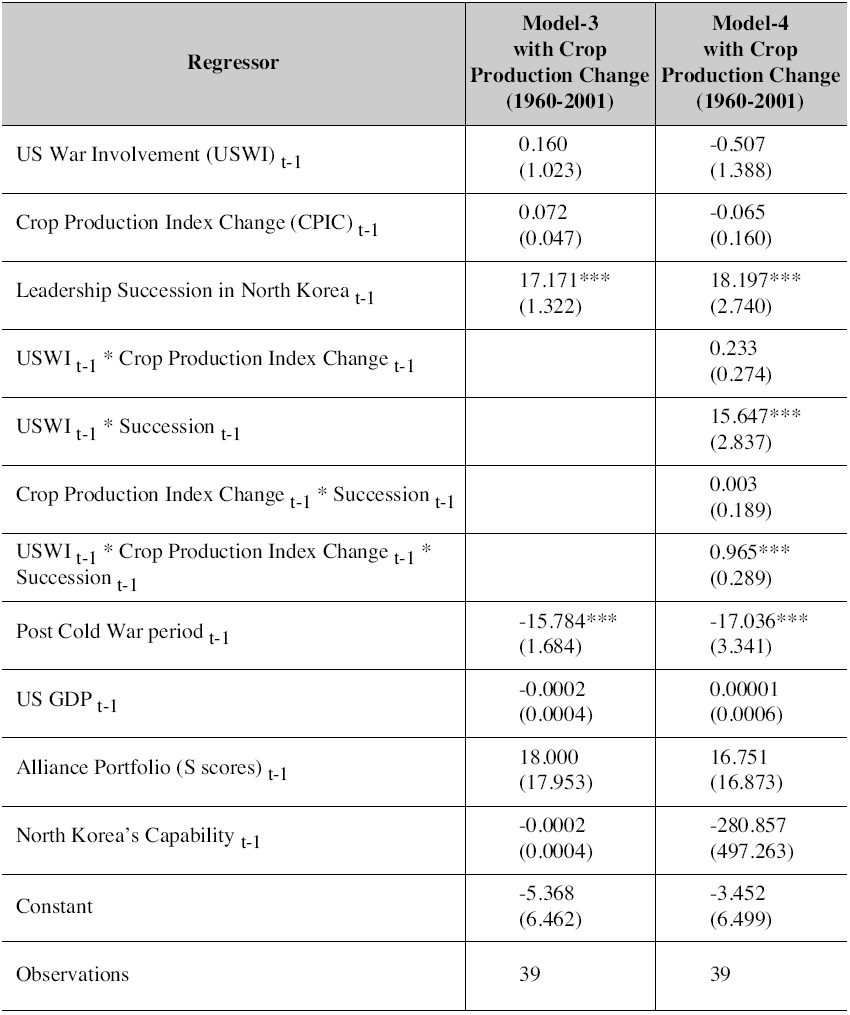

The results in Table 1, however, are based on the data that covers only 29 years. In turn, it may violate the central limit theorem that requires a sample size of at least 30 to obtain the normally distributed sample mean. To account for a possible methodological flaw, I employ North Korea’s

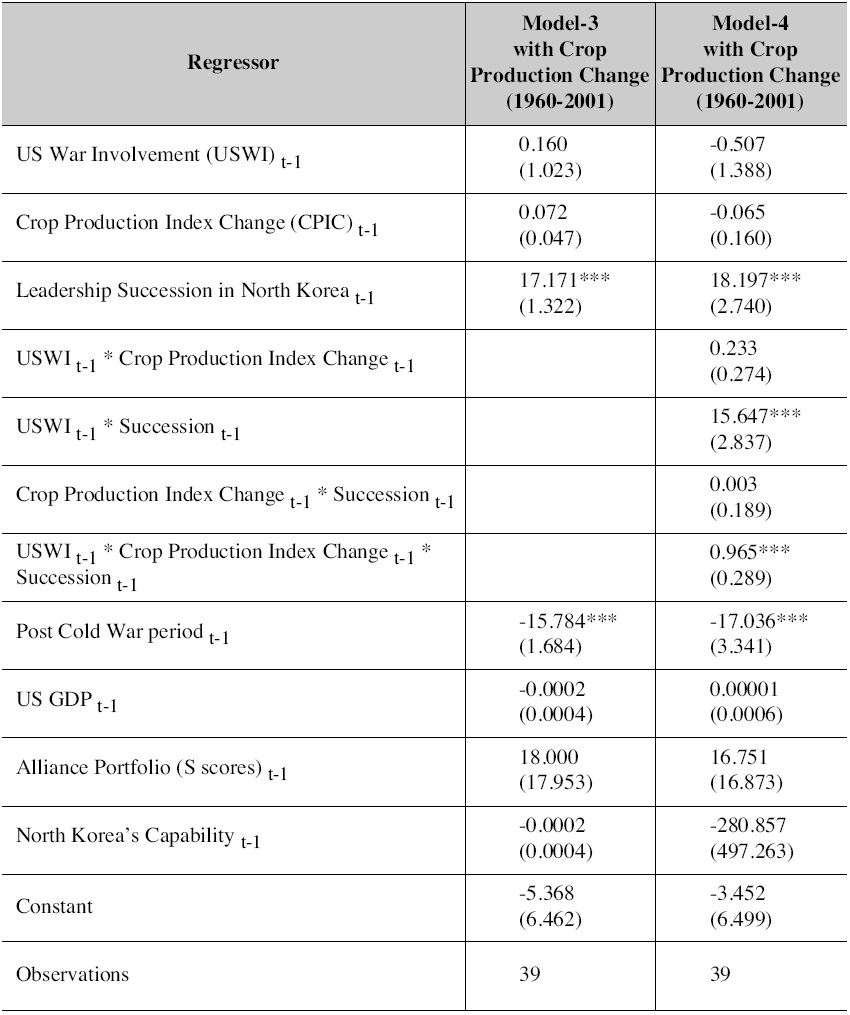

Table 2 presents the logistic models testing the relationship between North Korea’s conflict behavior and changes in its crop production representing North Korea’s economic conditions. Even if a different measure is used to operationalize the same concept, the results in Models 3 and 4 are almost identical to those in Table 1. For instance, Model 3 displays that

[Table 3.] Logit Analysis of North Korea’s Conflict Behavior (with Crop Production)

Logit Analysis of North Korea’s Conflict Behavior (with Crop Production)

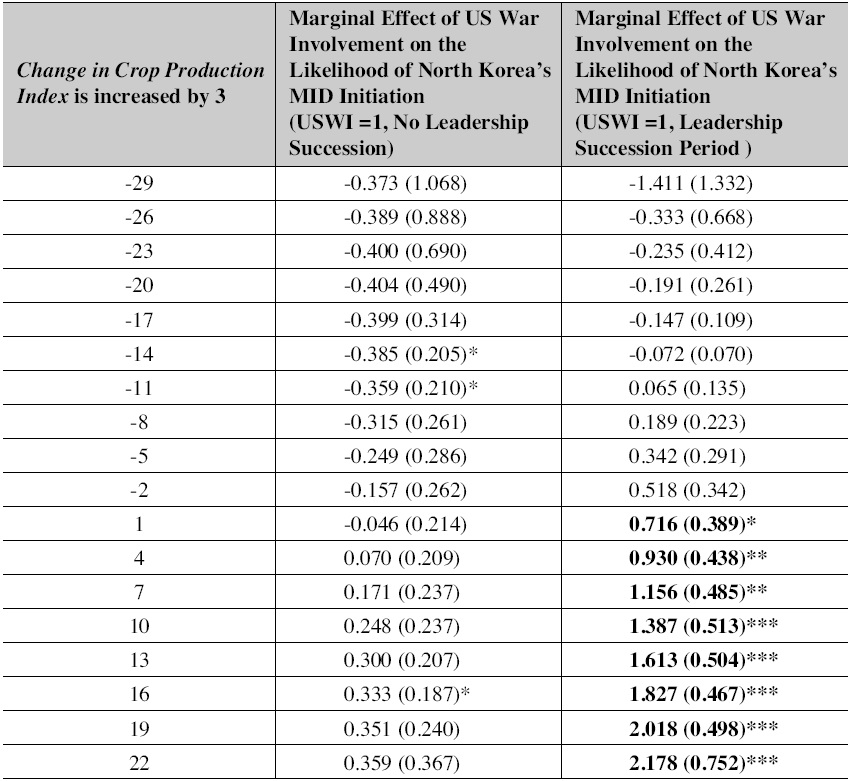

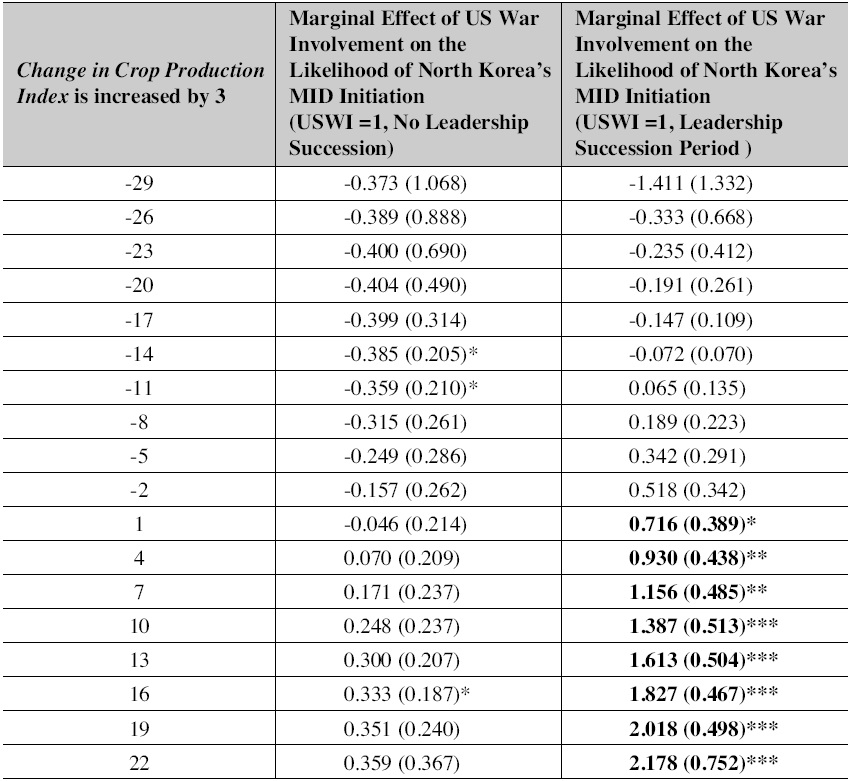

Three-way Interaction - Marginal Effect of US War Involvement on the Likelihood of North Korea’s MID Initiation as Crop Production and Leadership Succession Change

To understand quantities of interest in Model 4, Table 4 depicts the marginal effect of U.S. War Involvement on the dependent variable as North Korea’s crop production index increases by 3. Distinct from results in Table 2, Table 4 displays that when North Korea is not in the period of leadership succession (1989-1999), both the

The results connote that when North Korea is in the leadership succession period or stabilizing its leadership after succession, North Korea is more likely to exploit the US preoccupation derived from its wars with other states by initiating militarized interstate disputes against South Korea and its allies only if its crop production increases. The possible reasons are two fold. First, the increase in its crop production allows North Korean leaders to pursue additional leverage that augments the stability of its new leadership. Second, it gives North Korea confidence by alleviating the problems of logistics if its military provocations escalate into a full-scale war.

Albeit the level of verisimilitude between results in Table 1 and Table 3 appears to be fairly high, the analysis reveals that North Korea’s economic recession is negatively related to the likelihood of its MID initiation whereas its crop production is positively associated with it. In other words, the effect of North Korea’s economy on the dependent variable varies. The substantive meaning of this result is that when North Korea is not in the leadership succession period, its economic recession encourages it to exploit the US preoccupation by pursuing hawkish foreign policies against South Korea and its allies, such as the commando raid on the Blue House (January 21, 1968) and capture of the USS Pueblo (AGER-2) (January 23, 1968), and so forth. Conversely, when North Korea is in its leadership succession period, its positive crop production provides confidence for North Korean leaders. They are inclined to take advantage of the window of opportunity derived from the US war involvement by developing nuclear weapons (e.g., Kim Jong Il in 2003-current), attacking the ROKS Cheonan, testing long-range missiles, and so forth.

Among control variables, only the variable of the post-Cold War period is negatively associated, on average, with the likelihood of North Korea’s MID initiation, holding other variables constant. However, North Korea’s military capability, its strategic conflict avoidance movement, and alliance portfolio similarity with the United States do not show any significant impact on the likelihood of MID initiation. Overall, these results indicate that the US hegemony in the post-Cold War period generally deters North Korea’s conflict behavior. Alliance, arms race, and the US economy are relatively less important factors than leaders’ political survival (e.g., economy and leadership succession) and strategic context (e.g., US preoccupation and US hegemony in the post-Cold War period) to North Korea in deciding the initiation of militarized interstate disputes against South Korea and its allies.

24)William Clark, Michael Gilligan, and Matt Golder, “A Simple Multivariate Test for Asymmetric Hypotheses,” Political Analysis 14 (2006), pp. 311-331.

Empirical results show that the reasons that North Korea has shown hostility toward South Korea and its allies are threefold. First, by and large, North Korea is likely to adopt hawkish policies during periods of leadership succession and transition. Second, US war involvement opens up a window of opportunity for North Korea to pursue its political objectives. Third, different types of economic factors, such as economic recession (-) or crop production (+), have distinctive effects on the likelihood of North Korea’s conflict behavior. Anchored in these findings, I provide three suggestions for policymakers.

1. Capabilities for Executing Information Operations

With regard to the first finding, I first suggest that, as both Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il initiated nuclear development and hostile foreign policies during their leadership succession and transition periods, South Korea and its allies should pay extra attention to North Korea in the current period of Kim Jong Un’s succession and transition. North Korea’s attack on the ROKS Cheonan and shelling of South Korea’s territory clearly warns what types of disasters South Korea and its allies would likely confront if they are not cautious about North Korea’s movements. Therefore, knowing that it is the most dangerous period, they should not let their guard down, but rather increase the information alert status, backed by C4, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) systems, in order to prevent further military provocations from North Korea.

2. New Doctrine, Strategy, and Means to Deter North Korea

As the second finding indicates, along with Iran, North Korea strategically takes advantage of its window of opportunity derived from the US preoccupation with two ongoing wars. Thus, even if South Korea and the United States have maintained a strong military alliance since the ROK-US Mutual Defense Treaty of 1953, this military alliance may seem to be less of a deterrent to North Korea in times of multiple US war involvements, as in the two ongoing conflicts. For instance, North Korea’s bold provocations confirm one of my key findings that North Korea’s militarized disputes against South Korea and its allies are more likely in times of limited or reduced US military capabilities. As a result, in addition to continuously solidifying a military alliance with the United States, South Korea should build self-sufficient defense forces for a possible scenario in which the United States might be less able to provide a security umbrella due to its preoccupation with wars with other states.

Some military strategists assert that South Korea should spend a sizable military budget on upgrading anti-submarine capabilities. The reason is that North Korea has successfully destroyed a South Korean warship due to its asymmetric submarine capabilities. However, empirical findings demonstrate that the reasons for North Korea’s militarized disputes against South Korea vary. Hence, increasing the number of submarines might not completely deter North Korea’s future military provocations. Furthermore, the motivation of initiating its military conflicts is not solely derived from its relatively asymmetric submarines capabilities. Rather, it is more complex and politically driven. Hence, the right solution to nullify North Korea’s strategies is that South Korea needs to retain appropriate tools to compel North Korea’s leadership to be changed. To be exact, South Korea should have an appropriate doctrine and equip lethal retaliatory attack capabilities.

Posen posits that if a state does not have a powerful ally, it should pursue an offensive military doctrine (e.g., Israel).25) However, if it lacks resources to defeat all security challenges from its enemies, deterrent doctrines are more recommendable. As he theorizes, South Korea has successfully defended itself with the US security umbrella due to its limited resources and military capabilities. However, North Korea’s torpedo attack on the ROKS Cheonan and direct shelling of Yeonpyeong Island occurred when the United States was preoccupied. Accordingly, I argue that South Korea should seriously consider adding the component of an offensive military doctrine to the existing one. Given this political juncture, the current reform in doctrine from the former military strategy, ‘defense by denial,’ to ‘proactive deterrence strategy,’ is the right direction to thwart North Korea’s strategic calculations.26) Adopting it as a national military strategy will help South Korea’s coercive diplomacy work even in the limited presence of strong allies’ assistance. Moreover, it will clearly send a signal that South Korea will aggressively act in response to North Korea’s military provocations. This type of more realistic and effective tit-for-tat strategy will ultimately deter North Korea’s military provocations. It will enable South Korea to accomplish a victory without fighting, a policy emphasized by Sun-Tzu.27)

The next question is what are the most effective means that make the proactive deterrence strategy work. Someone might claim that possessing nuclear weapons can be a powerful deterrent. However, initiating a nuclear arms race is not in the South Korean government’s interest because South Korea is a member of the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) and the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) which limit the development of long-range missiles and nuclear weapons.

Are there any other options that South Korea can use to overcome North Korea’s asymmetric nuclear advantage? Although various policies and military strategies have been recommended and executed in order to deter North Korea’s unpredictable conflict behavior, we have failed to resolve the problem. In order to achieve deterrence even in a situation where the United States is vulnerable, South Korea should find a dominant asymmetric power that allows it to counterweigh the effect of North Korea’s nuclear weapons and other asymmetric capabilities. Among many lethal military weapons, such as surface to surface cruise missiles, missile defense system, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), aircraft capable of strategic bombings, and so forth, I suggest that attaining stealth fighters is a relatively viable option to deter North Korea’s attempts. The reasons are twofold.28)

First, stealth fighters can effectively thwart any type of threat from North Korea. North Korea’s heavily fortified air defense system and potential nuclear retaliation capabilities discourage South Korea and its allies from choosing military punishment even if North Korea intentionally violates the armistice agreement for fear of all-out war between the two Koreas. Hence, North Korea repeatedly provoked conflicts in 1999, 2001, and 2010 in the Yellow Sea, and it boldly threatened neighboring states by testing missiles and nuclear weapons in 2006, 2009, and 2012. However, if South Korea possesses stealth fighters supported by full-fledged C4ISRPGM capability,29) they are independently able to assume counterattacks without the risk of being identified by North Korea’s defense system while not inflicting major collateral damage.30) Furthermore, stealth capabilities allow South Korea to surgically eliminate North Korea’s nuclear facilities in Yongbyon and some other areas, if necessary, by itself even if the United States is preoccupied with other commitments.

Second, stealth fighters can generate greater fear among North Korea’s leadership than other types of existing military weapons. Empirical findings indicate that the causes of military conflicts between the two Koreas mainly stem from Kim Jong Il and his winning coalition. Thus, the center of gravity should be North Korea’s leadership. Given this situation, threatening to undertake massive counterattacks on North Korea’s leadership by stealth fighters is a more credible option than others. It is likely to deter North Korea’s further military provocations.

In sum, I argue that the unique and resounding capabilities of stealth aircraft as well as the Proactive Deterrence Strategy justifying the use of stealth capabilities in response to North Korea’s attacks would be more likely to dissuade North Korea from pursuing both diversionary conflicts and hawkish foreign policies against South Korea and its allies.

The results evince that the effect of North Korea’s leadership succession and the US war involvement on the likelihood of North Korea’s MID initiation is modified by different types of economic factors. To be specific, changes in North Korea’s economic growth rate and crop production affect the likelihood of North Korea’s conflict behavior in an antithetical direction. For instance, North Korea’s economic recession has prompted leaders to initiate militarized disputes with South Korea and Japan in times of US war involvement. Conversely, in times of less involvement of the United States in war commitments, North Korea has not been hostile toward its neighboring states even when its crop production declined. Interestingly, it has been more hawkish toward them when its crop production increases in the presence of the US war involvement and during periods of leadership succession and transition.

Implications rooted in empirical findings tell us that providing rice for humanitarian purposes to North Korea without monitoring where it goes may not solve its prevalent hunger problems. Instead, the aid is more likely to end up helping North Korea’s militarization because it tends to go to North Korea’s military personnel due to its military-first policy. In other words, the direct help with crops from international societies including South Korea and its allies has unintentionally helped North Korean soldiers. This will lead us to undergo more of North Korea’s imprudent military adventurism.31)

To soothe North Korea’s agitated and conflictual behavior against South Korea and its allies, first, I suggest that international societies refrain from providing direct humanitarian aid without establishing transparent food distribution monitoring systems operated by international organizations or non-governmental organizations. Second, they should strive to change North Korea’s economic infrastructure using the Kaesong Industrial Complex, Kumkang Mountain Tourism, and so forth. These types of low politics are sometimes more effective than high politics because gradual exposure to western societies is more likely to trigger relative deprivation among North Korean people.32) North Koreas may question their government’s capability as they are dissatisfied with how they have lived. They may collectively move to rebel. Such a scenario would eventually disable North Korea’s attempt to resort to military provocations if it suffers from economic recession.

25)Barry R. Posen, “The Sources of Military Doctrine,” in Robert J. Art and Kenneth N. Waltz (eds.), The Use of Force: Military Power and International Politics (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2009), pp. 23-43. Posen argues, “Statesmen will prefer offensive military doctrines if they lack powerful allies, because such doctrines allow them to manipulate the threat of war with credibility. Offensive doctrines are best for making threats. States can use both the threat of alliance and the threat of military force to aid diplomacy in communicating power and will. In the absence of strong allies, the full burden of this task falls on the state’s military capabilities” (p. 35). 26)Proactive deterrence strategy is a newly developed concept by the ROK Ministry of National Defense. It states that if North Korea attacks South Korea, South Korea will answer with a swift, devastating counter-strike against the origin of the attack and enemy supporting groups. 27)Sun Tzu, The Art of War, trans. by Thomas Cleary (Shambhala: Boston & Sharfesbury, 1988). 28)An anonymous reviewer points out that the discussion regarding stealth aircraft has nothing to do with my empirical findings. However, knowing that North Korea strategically exploits the vulnerability of the United States, logically, having stealth fighters in South Korea can be a powerful deterrent against North Korea. Moreover, stealth capabilities in general are also applicable to other areas including navy warships, army helicopters and so forth. I presuppose that stealth technology transfer that may come with purchasing stealth fighters will galvanize the development in this area. Based on this reasoning, I attempt to provide a constructive policy option for decision-makers. I would like to confirm that this suggestion does not stem from my personal preference. It is based on the analysis with regard to the existing military weapon systems. 29)C4ISRPGM stands for Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance, and Precision Guided Munitions. 30)John T. Correll, “Strategy, Requirements and Forces: The Rising Imperative of Air and Space Power,” an Air Force Association Special Report (Arlington, VA: Aerospace Education Foundation, 2003); David A. Deptula, “Effects Based Operations: Change in the Nature of Warfare” (Arlington, VA: Aerospace Education Foundation, 2001); Hong-Cheol Kim, “Hyogoa Kiban Jagjeon-goa Gyeoljeongjeog Sinsog Kidong Jagjeon Hanbando Jeogyong Ganeungseong” [The Assessment of Applicability of Effect Based Operations and Rapid Decisive Operations on the Korean Peninsula], Kongkun Pyeongron [Air Review] 114 (2004), pp. 7-59. 31)During the series of formal discussions over the resumption of the Six-Party Talks, North Korea consistently requested rice and other economic aid in return for participating in the multilateral talks. This case clearly reveals that North Korea is in a dire economic situation. More importantly, using military provocations to obtain what North Korea needs from other states is the time-worn hackneyed strategy adopted by the Kim family regime. Therefore, supplying rice and other aid to North Korea will not deter its further military provocations. Rather, it will help North Korea inflict more militarized conflicts against South Korea and its allies whenever North Korea desires to achieve something. 32)Ted Robert Gurr, Why Men Rebel (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1970).

This article identifies reasons why North Korea initiates militarized disputes against South Korea and its allies. The results of the analysis point to a combination of factors to explain such North Korean behavior: North Korea’s leadership succession and transition, US preoccupation with war, North Korea’s economic recession and the increase of North Korea crop production.

Given these findings, possible solutions to deter future provocations are as follows. To begin, South Korea should employ a tit-for-tat strategy to deter North Korea because cooperation between rivals lies not in being amenable to the enemy’s demands but in reciprocity with each other.33) If a state does not respond quickly to a provocation, that state risks sending the wrong signal to its opponent. Eliciting cooperative behavior is likely to be more difficult. Hence, deterrence is complete only through the firm foundation of a strong reputation-that is, South Korea does not tolerate any type of military provocations.

In order to accomplish peaceful relations with North Korea, South Korea must have dominant asymmetric capability that forces North Korea to believe that its military provocations will automatically bring about severe military punishment from South Korea. The longer North Korea’s conflict behavior goes unchecked by South Korea, the more North Korea will be inclined to believe that its brinksmanship strategy is effective. In the end, this would lead South Korea to undergo similar pain repeatedly. Thus, South Korea should adopt a proactive deterrence strategy, attain stealth fighters supported by fully developed C4ISRPGM capabilities, and devise more realistic and effective economic policies that can induce changes in North Korean society.

Implementing these strategies and policies will breathe new life into the failed deterrence mechanism on the Korean peninsula. This would create the most credible threat that generates fear in North Korean leaders and reduces the asymmetric advantage of North Korea’s nuclear weapons. While other types of feasible solutions may exist, they are the domain of future research.

33)Robert Axelrod, The Evolution of Cooperation (New York: Basic Books, 1984).