The present study examined the capacity of Korean adolescents’ self-esteem to buffer against the negative impact of academic stress on self-control. Based on the prevention science perspective, the conceptual framework for this study was developed from the strength model of self-control. Data for the present study were taken from the fourth wave of Korean Youth Panel Study. A sample of 2,169 students in the eleventh grade was analyzed to identify relationships between the study variables. As expected, self-esteem moderated the association between academic stress and self-control. Implications for the study findings are discussed.

본 연구는 우리나라 청소년의 학업스트레스와 자기통제의 관계에서 자아존중감의 조절효과를 검증하는데 목적이 있다. 이를 위하여 자기통제 힘 모형을 예방과학적 관점으로 조명하여 연구의 분석틀로 설정하였다. 연구문제 및 가설을 검정하고자 한국청소년패널조사(KYPS)의 중학교 2학년 패널 4차년도 자료를 활용하였으며, 일반 고등학교 2학년에 재학 중인 2,169명의 청소년을 연구참여자로 선정하였다. 분석 결과, 학업스트레스가 자기통제에 미치는 영향에 대하여 자아존중감의 조절효과가 확인되었다. 즉, 학업스트레스는 자아존중감의 수준과 상관없이 청소년의 자기통제를 저하시켰다. 그러나 자아존중감이 높은 청소년의 경우, 자아존중감이 낮은 청소년에 비해 더 높은 수준의 자기통제를 가지고 있었으며, 학업스트레스가 높은 상황에서 자아존중감이 학업스트레스가 자기통제에 미치는 부정적인 영향력을 완화시키고 있었다. 이러한 연구결과에 기반하여 함의를 논하였다.

Being a Korean adolescent is stressful due to pressures coming from enormous academic demands (Jung, 2011; Lee, 2003; Lee & Larson, 2003; Ministry of Health and Welfare [MOHW], 2006). Among the various socio-ecological stressors that Korean adolescents experience, academic-related stressors ranked first (Yom & Cho, 2007). Korean adolescents have been suffering under an examination-focused educational system and a societal atmosphere of the survival of the fittest. Researchers have argued that most Korean adolescents’ issues are generally derived from the competitive school atmosphere which exceedingly emphasizes the academic achievement (Kang & Jeong, 1999; Moon, 2006; Lee, 1995 as cited in Moon, 2008; Moon & Jwa, 2008).

Strenuous academic requirements act as a burden on physical and mental health among adolescents (Jwa, Moon, & Yoon, 2008; Kim, Lee, Kye, Park, & Song, 2002; Lee & Larson, 2000; Moon & Jwa, 2008; Moon, 2008; Yoon & Nam, 2007). Especially, academic stress has been known as an unpleasant factor contributing to adolescents’ capacity for self-control (Han, 2007; Song, 2010). According to Baumeister, Vohs and Tice (2007), unrelenting and fixated use of mental energies on certain tasks lowers one’s level of self-control significantly. Under unfavorable circumstances where adolescents are kept from restoring their lost strength, self-control resources get depleted. Issues such as deviant behaviors (Beichler-Robertson, Potchak, & Tibbetts, 2003; Finkernauer, Ruther, & Baumeister, 2005; Unnever & Cornell, 2003), procrastination (Baumeister et al., 2007), delinquency (Lee, 2002), psychiatric disabilities (Tangney, Baumeister, & Boone, 2004), maladjustment (Mo, Kim, & Yu, 2010; Tangney et al., 2004), substance abuse (Wills & Stoolmiller, 2002) and relationship problems(Baumeister et al., 2007) are reported as socio-psychological phenomena where one’s self-control is at risk of exceeding the normal capacity for restoration.

In Korea, about one-tenth of high school students are estimated to show addictive behaviors on the Internet (Ministry of Public Administration and Security, 2010). Adolescents’ crime rate reached 4.5% of the Korean national total (Supreme Prosecutor’s Office, 2010). The smoking and drinking rates among Korean adolescents in general high schools are 12.2% and 24.8%, respectively (MOHW, 2012). The fact that a great deal of adolescents’ individual, communal, and social problems originate from self-control failure (Beck, 1976; Cho, Choi, & Seo, 2010) makes it crucial to examine how academic stress is associated with self-control and how to mitigate its effect on self-control.

Many research findings have shown that self-esteem can alleviate the immediate negative consequences of stress (Han & Hur, 2005; Shin, 2008; Trumpeter, Watson, & O’Leary, 2006). This sense of self-competence and self-worth is also known to assist the accomplishment of adolescents’ socio-psychological developmental tasks (Yoon & Choi, 2011). Recently, self-esteem has been conceptualized more as a buffer (Rosenberg & Pearlin, 1978), protecting individuals from the unfavorable consequences of harmful experiences (Weissberg, Kumpfer, & Seligman, 2003). This suggests that self-esteem might benefit self-control among those struggling with academic demands. However, capacity of self-esteem in moderating the influence of the academic stress on self-control among adolescents in Korea has not yet been examined.

The present study aims to investigate the relationship between academic stress and self-control among Korean adolescents with a specific focus on examining the moderating effect of self-esteem that mitigates the association between academic stress and self-control. The hypothesized relationships among the study variables are developed according to the strength model of self-control (Baumeister et al., 2007) in the preventive scientific perspective with an adaptation to reflect data from the fourth wave of Korean Youth Panel Study. This study will contribute to designing educational policies and providing social welfare services for Korean adolescents. Moreover, the current research carries significant implications as the first attempt to utilize the strength model of self-control (Baumeister et al., 2007) for Korean adolescents, expanding the applicability of the model into the Korean social welfare context.

Based on the research objectives, the current study addresses the following research questions:

1. Self-control in Adolescents

A broad range of socio-psychological problems, such as addiction, spending sprees, binge eating, delinquency, and procrastination, all stem from individuals’ inability to control themselves (Baumeister & Todd, 1996; Baumeister et al., 2007). Researchers have recognized self-control as a significant contributing factor to the successful social adjustment and intellectual achievement of adolescents (Cho et al., 2010; Mo et al., 2010; Tangney et al., 2004). Self-control has recently drawn more attention as an essential human capacity in this achievement-oriented society (Park & Lee, 2011).

Self-control refers to individual’s competence in altering his or her own responses to live up to social expectations as well as life purposes (Baumeister et al., 2007). Self-control places its conceptual foundation on reciprocal determinism (Kim, 2010; Lee, 2001a). According to Bandura (1986), human behavior is determined not only by environmental influences but by internal processes as well. This indicates that individuals modify their own behaviors by mediating environmental cues through goal setting, comparative evaluation, self-acknowledgement, and self-criticism (Kim, 2010). Self-control research adopting the reciprocal determinism model has conceptualized self-control as resistance to temptation, delay of imminent gratification and inhibition of impulses (Harter, 1983; Song, 1995 as cited in Lee, 2001a).

The literature on self-control shows that low levels of self-control are significantly associated with adolescents’ maladjustment behaviors and emotional problems (Finkernauer et al., 2005; Lee, 2002; Mo et al., 2010; Morris, Wood, & Dunaway, 2006; Schmeichel et al., 2003; Wills & Stoolmiller, 2002). Low self-control also induces academic under-achievement in educational settings (Feldman & Wentzel, 1990; Kim & Kim, 1999 as cited in Lee, 2001a; Tangney et al., 2004). On the other hand, high levels of self-control are positively related with obedience to law and rule, initiation and maintenance of relationships, and coping with risks (Cho et al., 2010). Moreover, this distinctive human capacity is important in the sense that it significantly influences the accomplishment of developmental tasks among adolescents and predicts a successful adulthood (Shaffer, 2000 as cited in Mo et al., 2010; Shaffer, 1999; Keenan & Vondra, 1994 as cited in Park & Lee, 2011).

2. Academic Stress and self-control

The capacity for self-control is best understood in its dynamic interaction with socio-cultural environments (Mo et al., 2010). Thus, Korean adolescents’ self-control is most appropriately discussed in the Korean-specific context where pressures to do well on the highly competitive university entrance examination are considered to be one of the most serious stressors (MOHW, 2006).

Academic stress refers to the stress stemming from academic problems or to states where one suffers from socio-psychological tension while struggling with the strenuous or tiresome academic requirements (Jwa, Moon, & Yoon, 2008). By taking a perspective on stress not as a mere response to stimulus but as a process of interaction between an individual and his or her environment (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985), the current research conceptualizes academic stress as a particular relationship with the academic environment that an individual perceives as a menace to his or her well-being or as depleting his or her resources as a result of exceeding its limits.

The Korean college scholastic ability test is administered nationwide at the end of every year to high school seniors. Due to the great benefits associated with going to a prestigious university, such as a good job, a good marriage, and high social status (Bae & Lee, 1988 as cited in Lee, 2000), students put enormous effort and time into studying. According to Lee and Larson (2003), Korean youths spend as much 14 to 18 hours a day studying, giving up sleeping and leisure activities. Undoubtedly, high school students are involved in a continuous, high level of mental functioning as they spend every possible minute preparing for the examination, with stark consequences for self-control.

The Strength Model of Self-control (Baumeister et al., 2007) well supports the relationship of academic stress, namely the Korean ‘Examination Hell’ (Lee, 2003), and decreased levels of self-control in adolescents. Baumeister and colleagues (Baumeister & Todd, 1996; Baumeister & Vohs, 2004; Baumeister et al., 2007; Muraven & Baumeister, 2000; Schimeichel et al., 2003) argue that the constant, focused consumption of mental energies on certain objects is costly as it consumes crucial resources and thus results in the lower levels of self-control. Individuals normally recover their strength under favorable circumstances; however, under circumstances that keep them from regaining their lost strength, they become impaired of self-control. Depletion of self-control resources debilitates performance on tasks that require self-control capacity (Schmeichel et al., 2003).

Self-control is the foremost virtue among various disciplines, including prudence, equity, moderation and endurance (Baumeister, 2012); however, the self-control of Korean adolescents who have been under academic stress is at risk, and thus it is essential to identify the socio-psychological resources that moderate the influence of academic stress on the failure of self-control.

3. Self-esteem, a Socio-psychological Resourece

Self-esteem refers to an individual’s overall positive or negative evaluation of themselves (Gecas, 1982; Rosenberg et al., 1995). The construct is thought to be composed of two dimensions - competence and worth (Gecas, 1982; Gecas et al., 1983 as cited in Longmore, 1997). A substantial amount of research models self-esteem as an independent or dependent variable to address developmental issues among adolescents (Kaplan, 1975 as cited in Cast & Burke, 2002; Han & Hur, 2005; Shin, 2008; Trumpeter, Watson, & O’Leary, 2006; Rosenberg, 1979).

Self-esteem has recently been studied as a factor that buffers the influence of stress on the psychosocial health and development of adolescents, thereby preventing them from stress-induced outcomes. Park and Lee (2008) found, in their research of resilience, self-esteem moderated the deviant peer’s influence on delinquency among adolescents. Higher levels of self-esteem among distressed adolescents acted as a buffer against the impact of the threatening experiences (Flaser et al., 1990 as cited in Choi, 2009). Moreover, self-esteem was reported to ameliorate the negative effects of the interpersonal anxiety on adolescents’ negative emotion (Kim, 2010). Self-esteem also worked as a protective individual characteristic in the association between parents’ problem drinking and adolescents’ socio-psychological adjustment in a study on the children of alcoholics (Choi, 2009).

High self-esteem often accompanies a competent level of self-control; however, the two are viewed in a social science as distinct constructs (Cho et al., 2010). Self-control regulates one’s impulses, altering emotions and thoughts and restraining undesirable behaviors in such a way as to fit the surrounding environment and situation. To do this, it is first necessary to evaluate the self accurately (Cho et al., 2010). In other words, adolescents’ self-esteem provides important socio-psychological resources for their self-control capacity (Yoon, 2011). For example, Shin (2008) found that high self-esteem of adolescents is a significant factor in impulse restraint and the delaying of imminent need satisfaction. Han and Hur (2005), in their research, also reported that adolescents who regard themselves as valuable reported higher self-control levels than those with lower self-worth. Furthermore, self-esteem is considered as a contributing factor in influencing adolescents’ socio-psychological developmental trajectories and is indicated as an essential factor in explaining variance in self-control beyond adolescence (Trzesniewski, Donnellan, Moffitt, Robins, Poulton, & Caspi, 2006).

Although studies have shown that adolescents’ self-esteem is significantly related to self-control, self-esteem has not yet been employed as a moderator for the depletion of self-control among adolescents who are struggling with enormous academic pressures. Given the limitations, the present study aims to examine the moderating effect of self-esteem on the association between academic stress and self-control. Namely, the levels of self-esteem might account for the difference between those adolescents who lose self-control and those who do not when exposed to a stressful situation. Such examination of the buffering effect of self-esteem carries significant implications, especially in response to the growing call for the identification of a human capacity in the preventive scientific perspective.

The present study aims to examine the moderating effect of self-esteem on the relationship between academic stress and self-control in adolescents. Figure 3-1 presents the conceptual framework of the current research, which is developed from the strength model of self-control (Baumeister et al., 2007) in the preventive scientific perspective.

Data for the current study were taken from the fourth wave of Korean Youth Panel Survey (KYPS) (National Youth Policy Institute, 2007). KYPS surveyed adolescents nationwide excluding Jeju Island, utilizing stratified multi-stage cluster sampling from 2003 to 2008. The fourth wave, conducted from October, 23rd to December, 22nd in 2006, consisted of 3,121 respondents. Of these participants, 2,312 students were currently attending high schools. The sample was limited to those attending high schools with respect to the aim of the study. By considering the grade distribution, eight students found to be in the tenth grade were excluded. This exclusion was employed since the participants of KYPS were in the eighth grade in 2003 (i.e., the first year) and thus being in the eleventh grade was normal in 2006, according to the formal academic course.

The loss of 135 cases due to missing data regarding control variables would not necessarily introduce bias into the findings; 135 cases from family structure, 73 from monthly household income and 1 from perceived relationship with friends. Cases with missing values for family structure have been excluded in the analysis, and those for monthly household income and perceived relationship with friends were replaced with variable means. The final sample comprised 2,169 respondents.

1) Dependent: Variable: self-control

In the present study, self-control is defined as the capacity for adjusting one’s own responses to bring into line with social expectations and long-term goals (Baumetister et al., 2007). Six items were included as self-control, with response options varied along a five point Likert scale, ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. ‘I do what is fun even though I have an exam the next day’, ‘I give up easily when things get rough’, ‘I tend to enjoy dangerous activities’, ‘I lose my mind when I get angry’, ‘I enjoy bullying others’, and ‘I seldom submit the homework on time’ were asked. Each item respectively pertains to impulsivity, simple task preference, risk taking, disposition, self-centeredness, and physical activity preference, which are the elements of self-control conceptualized by Grasmick, Tittle, Bursik, and Ameklev (1993). In the current research, items have been reversely recoded, with higher total scores indicating adolescents’ higher self-control levels. The scale score was calculated as the mean of the items. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for the scale was .669.

2) Independent Variable: Academic Stress

As for academic stress, four items confirming a unidimensionality as a result of exploratory factor analysis were measured (Moon & Jwa, 2008), with response options varied along a five point Likert scale, ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’; “I am stressed because of the unsatisfactory grades.”, “I am stressed because of the homework and the upcoming examination.”, “I am stressed because of the university entrance examination and the future employment.”, and “I am stressed because I am tired of studying.” The scale score was calculated as the mean of the items. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for the scale was .862.

3) Moderator Variable: Self-esteem

The moderator variable in the analysis was tapped with six items, which were found to match those of Rogenberg (1965)’s self-esteem scale (Cho, 2010); “I think I am a good-tempered person.”, “I think I am a capable person.”, “I feel that I am a person of worth.”, “I sometimes feel that I am useless.”, “I sometimes think that I am an ill-tempered person.”, and “I sometimes feel that I am a failure.” Of six items, three items reflecting a negative meaning have been reversely recoded, with higher total scores indicating adolescents’ higher self-esteem levels. Response options varied along a five point Likert scale, ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree.’ The scale score was calculated as the mean of the items. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for the scale was .760.

4) Control Variables

The variables predicting self-control in the previous studies (Cho et al, 2010; Hong, 2010; Lee, 2001a; Lee, 2001b; Lee, 2004; Park, Cho, & Kim, 2004) were employed as controls: adolescents’ gender, family structure, monthly household income (in 10,000 KRW), adolescents’ perceived relationship with parents (Cronbach’s alpha = .885), adolescents’ perceived supervision by parents (Cronbach’s alpha = .886), adolescents’ perceived relationship with teachers (Cronbach’s alpha = .787), adolescents’ perceived relationship with friends (Cronbach’s alpha = .813), adolescents’ perceived level of community atmosphere (Cronbach’s alpha = .845), and adolescents’ perceived supervision from community (Cronbach’s alpha = .767). As for adolescents’ gender, female was coded as ‘0’ and male was coded as ‘1’. As for family structure, ‘living with parents’ group was taken as a reference category and dummy variables of ‘living with a father’, ‘living with a mother’, and ‘living without parents’ were newly computed. ‘Monthly household income/the square root transformation of the number of family members’ was used as income. Due to the significant positive skew, log transformed values of income were used for the analysis. Adolescents’ perceived relationships with parents, friends, and teachers as well as perceived levels of supervision from parents and community were measured with response options varied along a five point Likert scale, ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree.’ These variables were calculated as the means of the items.

Data were analyzed using the SPSS 19.0 statistical package. Descriptive statistic analysis was first performed for socio-demographic factors and the major variables. Secondly, bivariate analysis was employed to present Pearson correlation coefficients among the study variables. In addition, multiple lineal regression analysis was conducted to examine the moderating effect of self-esteem on the association between academic stress and adolescents’ self-control. A main effect model was beforehand estimated to test globally for the presence of significant interaction.

1. The Socio-demographic Characteristics of the Participants

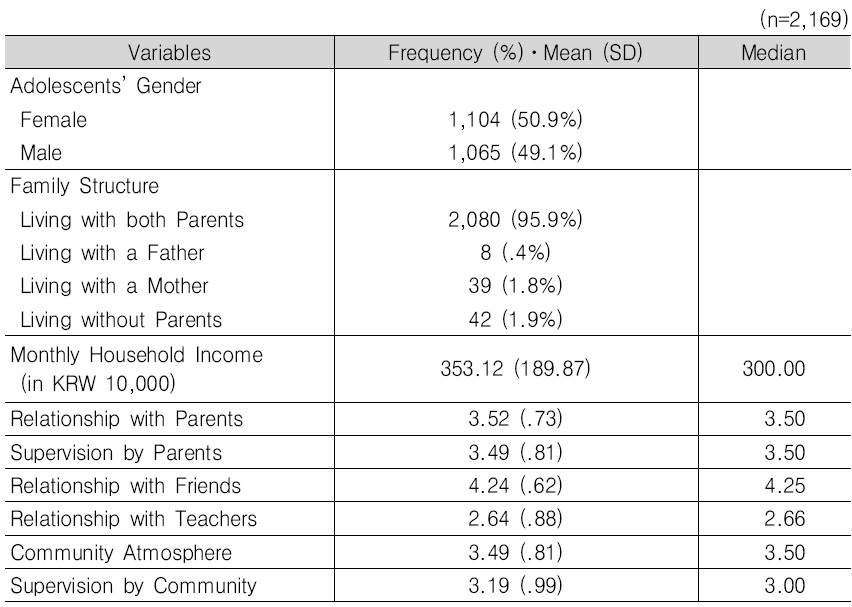

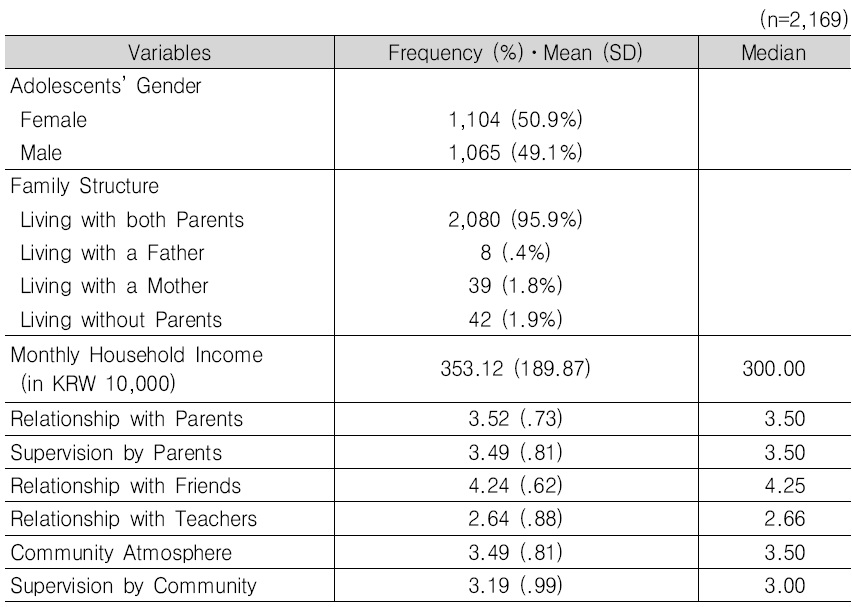

Descriptive statistics for the variables reflecting the characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 4-1, including frequencies, percentages, means, standard deviations, and medians. All values are for the uncentered variables.

Female adolescents (n = 1,104, 50.9%) take slightly larger number compared to males (n = 1,065, 49.1%). 95.9% (n = 2,080) of adolescents were living with both parents, .4% (n = 8) were living with a father, 1.8% (n = 39) were living with a mother, and the rest of adolescents (1.9%, n = 42) were living without any parent. The average monthly household income was reported as 353.12 (in 10,000 KRW) (SD = 189.87, Median = 300.00). The average score of perceived relationship with parents was 3.52 (SD = .73, Median = 3.50), and that of perceived supervision by parents was 3.49 (SD = .81, Median = 3.50). The average score of perceived relationship with friends was 4.24 (SD = .62, Median = 4.25) and that of perceived relationship with teachers was 2.64 (SD = .88, Median = 2.66). The level of adolescents’ perceived community atmosphere on average was 3.49 (SD = .81, Median = 3.50) and that of supervision from community was 3.19 (SD = .99, Median = 3.00).

[Table 4-1] Descriptive Statistics: Characteristics of Participants

Descriptive Statistics: Characteristics of Participants

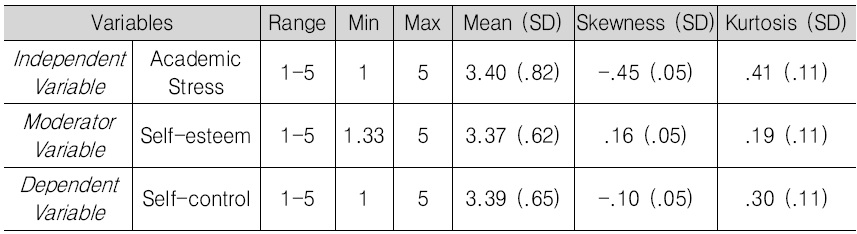

2. Descriptive Statistics of the Major Variables

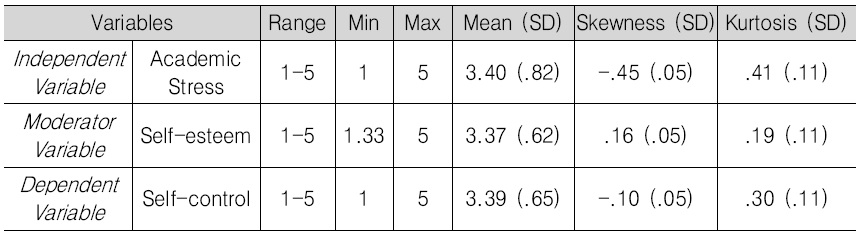

The major variables employed for the current study include adolescents’ academic stress, self-esteem, and self-control. Table 4-2 presents the descriptive statistics of the key variables. All values are for the uncentered variables.

The average score of adolescents’ academic stress was 3.40 (SD = .82). The values ranged from 1 to 5. The normality problem of the variable was not observed with skewness (-.45, SD = .05) and kurtosis (.41, SD = .11), as absolute value of skewness was less than 3 and that of kurtosis was less than 10 (Guiford, 1957 as cited in Choi, 2008). The average score of adolescents’ self-esteem was 3.37 (SD = .62). The values ranged from 1.33 to 5. The variable did not show any normality problem with skewness (.16, SD = .05) and kurtosis (.19, SD = .11). The average score of adolescents’ self-control was 3.39 (SD = .65). The values ranged from 1 to 5. The normality problem of the variable was not observed with skewness (-.10, SD = .05) and kurtosis (.30, SD = .11).

[Table 4-2] Descriptive Statistics: Major Variables

Descriptive Statistics: Major Variables

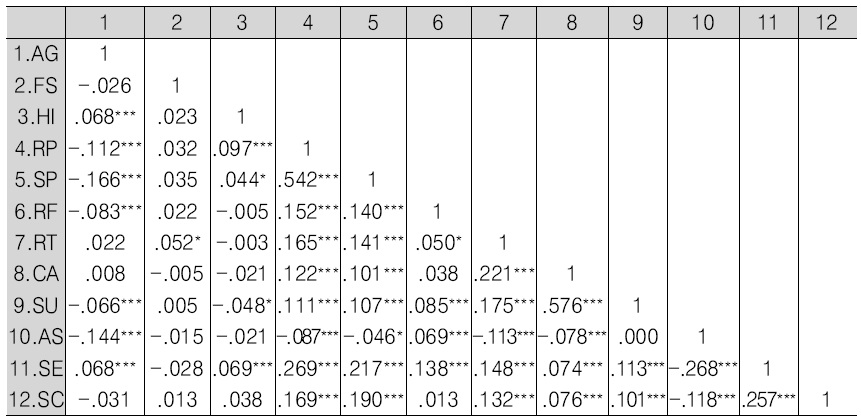

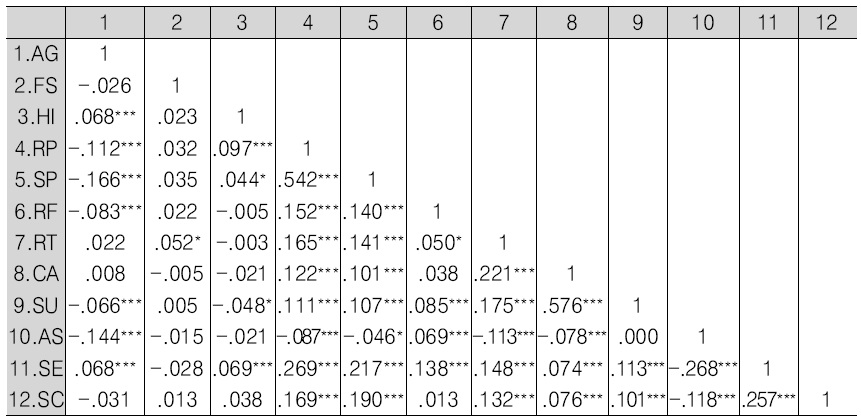

3. Correlation Matrix of the Major Variables

Simple correlation coefficients of the major variables computed by Pearson’s correlation formula are presented in Table 4-3. The existence of relations, magnitude of correlations, and direction of correlations among the variables are given in the correlation matrix (Choi, 2008). Large correlation coefficients which are greater than .60 indicate the presence of multicollinearity (Yoon, 2008). However, such a high degree of correlations was not observed in the present study.

[Table 4-3] Pearson Correlation Coefficients

Pearson Correlation Coefficients

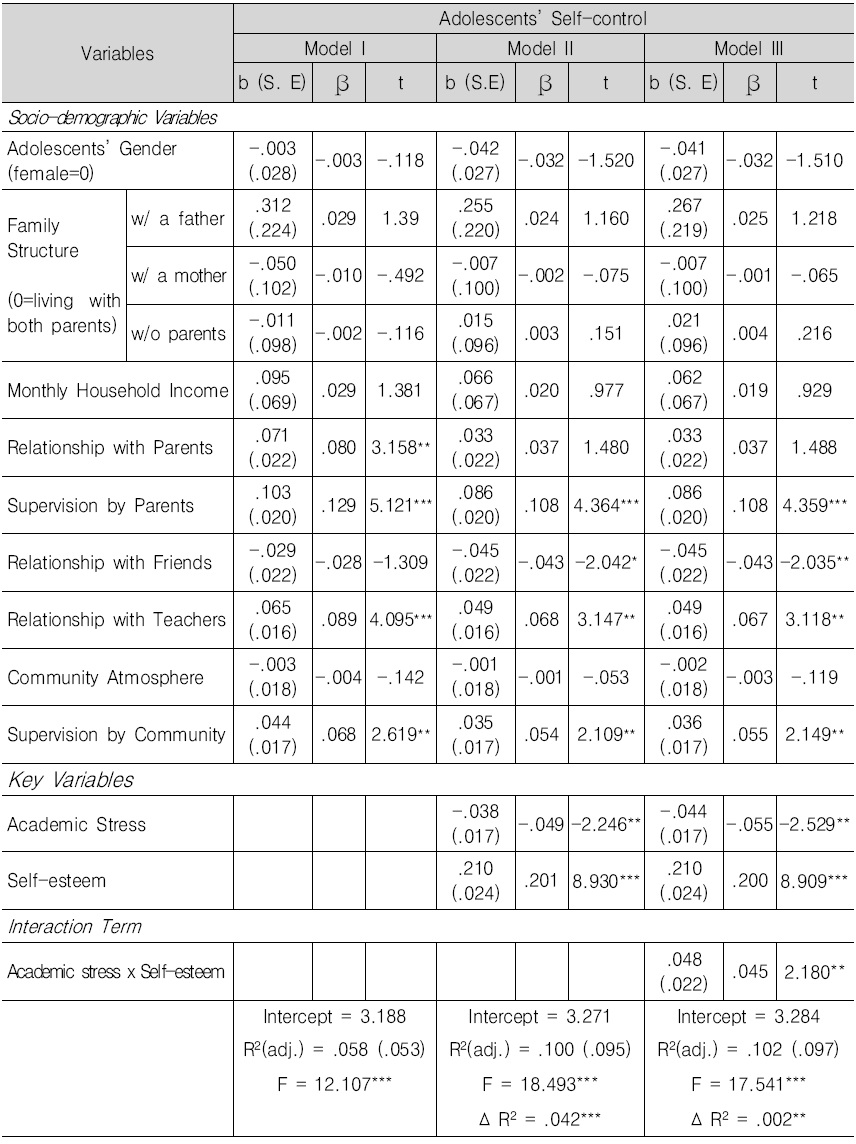

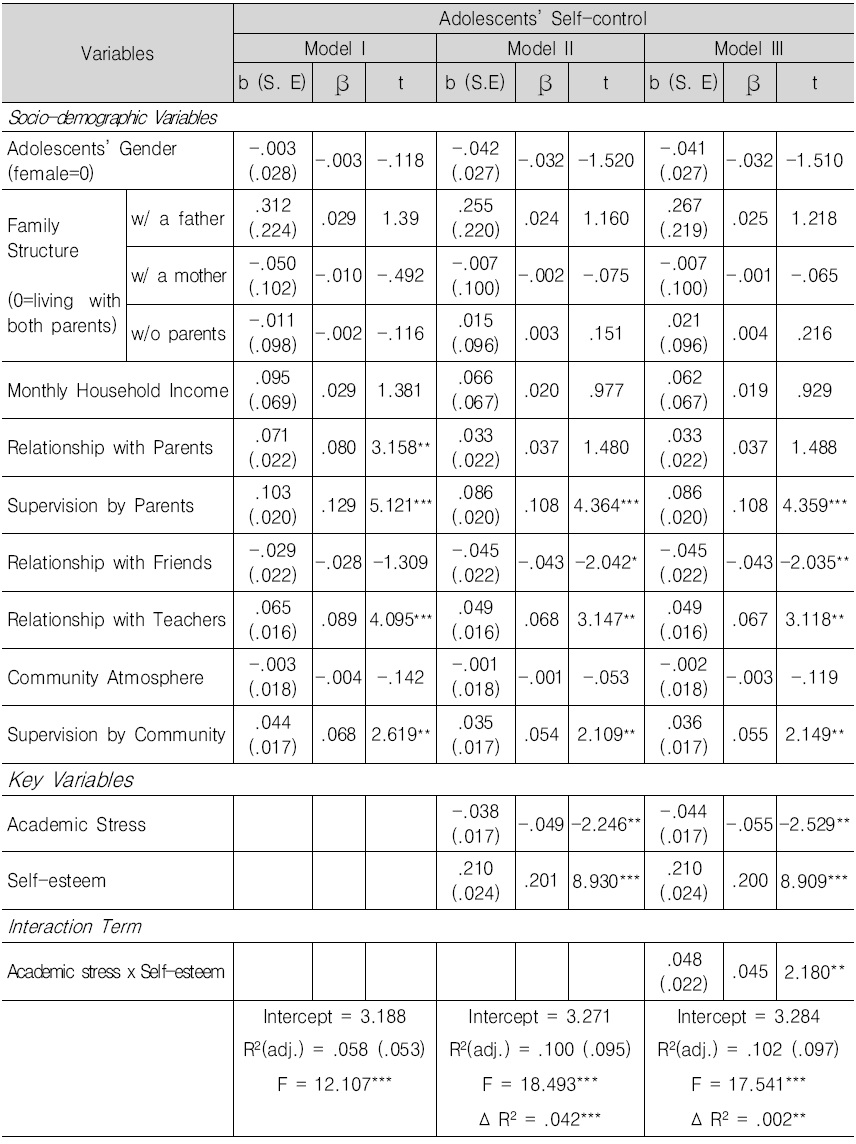

For the testing of the moderating effect of self-esteem on the association between academic stress and self-control, hierarchical regression analysis was employed by entering three blocks of predictors to examine the amount of variance in self-control explained by each block in the model; the first block: socio-demographic variables; the second block: academic stress and adolescents’ self-esteem; the third block: interaction term of academic stress and adolescents’ self-esteem. Variables except for the dummy variables were centered to eliminate multicollinearity issues (Aiken & West, 1991). The results of the analysis are presented in Table4-4.

[Table4-4] Testing the Moderating Effect of Self-esteem

Testing the Moderating Effect of Self-esteem

In Model I, self-control in adolescents was regressed on socio-demographic factors. The socio-demographic variables explained about 5.3% of the variance in adolescents’ self-control. As shown in Table4-4, adolescents’ relationship with parents, supervision given by parents, relationship with teachers, and supervision from community were found to have statistically significant positive associations with self-control (β = .080,

In Model II, the addition of academic stress and self-esteem variables, while holding socio-demographic variables constant, increased the explanatory power of the regression equation by about 4.2%p from Model I. In keeping with the assertion of Baumeister et al (2007), academic stress was found to debilitate the capacity for self-control (β =-.049,

Adolescents’ relationship with teachers, and supervision from parents and community still showed positive associations with adolescents’ self-control at a statistically significant level (β = .068,

Model III included the term representing the interaction of adolescents’ self-esteem with academic stress. The addition of the interaction term, while socio-demographic variables and key variables were held constant, increased the explanatory power of the regression equation by .2%p from Model II (

The effects of academic stress and self-esteem remained statistically significant in Model III (β =-.055,

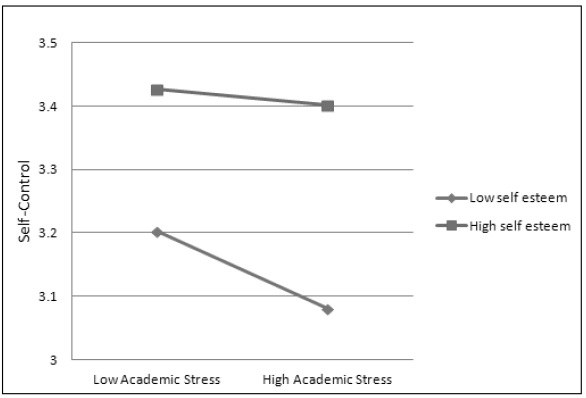

From the analytic results above, the buffering effect of self-esteem on the association between academic stress and self-control was observed. According to Aiken and West (1991), plotting the moderating effect improves the understanding on the relationships among the study variables. Scores at one standard deviation above the mean of self-esteem as well as at one standard deviation below the mean of self-esteem were respectively taken as high self-esteem and low self-esteem groups, keeping in mind that key variables were centered (Aiken & West, 1991, Cohen et al., 2003 as cited in Seo, 2010). The moderating effect of self-esteem on the association between academic stress and self-control is displayed in Figure 4-1.

Figure 4-1 shows the moderating effect of self-esteem on self-control among Korean adolescents struggling with academic stress. Academic stress leads to decreased levels of self-control. However, moderation in the negative association between academic stress and self-control is observed in adolescents with higher self-esteem. It has been substantiated that Korean adolescents’ self-esteem buffers against the negative impact of academic stress on self-control.

The present study investigated the influence of academic stress on Korean adolescents’ self-control with a specific focus on examining the moderating effect of self-esteem on the association between academic stress and self-control. The strength model of self-control (Baumeister et al., 2007) was employed as a conceptual framework in the preventive scientific perspective. The research findings showed that academic stress lead to decreased levels of self-control among Korean adolescents. As expected, the self-esteem of adolescents moderated the relationship between academic stress and their capacity for self-control, which indicates that adolescents with higher self-esteem are protected from the unfavorable consequences of academic stress, whereas those with lower self-esteem are likely to lose their self-control.

One of the major contributions of the current research is that hypothesized relationships among the study variables specified based on the strength model of self-control (Baumeister et al., 2007) were empirically examined with the study data. This study was the first attempt to adopt the model as a theoretical framework for Korean adolescents. As demonstrated in research findings, the applicability of the model to the study participants was validated.

The vast majority of research carried out in Korea to investigate self-control in adolescents has focused on those who are in need, taking a selective or indicated approach. The current research, however, identifies the preventive mechanism of self-esteem which mitigates the debilitating effects of academic pressures on the capacity for self-control among general high school students. In this respect, the present study contributes toward the building of an empirical foundation for preventive scientific research as well as the design and direction of related services. Furthermore, as the study utilized a nationally representative sample, its findings gained high generalizablity.

Programs designed to improve self-esteem among adolescents have proliferated across varied social welfare practice settings in Korea (Park & Lee, 2008), mostly in short-term sessions headed by a single independent organization targeting designated high risk groups; however, prevention that works requires coordinated and long-term efforts (Rogers, 2002). The universal prevention approach takes into account environmental factors such as family, school and community that support all adolescent groups without differentiation (Weissberg et al., 2003).

In Korea, school social workers might be one of the most relevant service providers in order to facilitate schools’ attempt to protect the capacity for self-control among general adolescents who are under academic stress. Since the late 1990s the school social work system was introduced in Korea, its comprehensive efforts on preventing and resolving problems related to students’ wellbeing have widely been acknowledged (Korea Association of School Social Workers, 2011 as cited in Cha, 2012). Moreover, providing preventive services in school settings has several advantages, including effectiveness, continuity, and accountability (Kim, 2008 as cited in Lee, 2011). Likewise, it carries significant practice implications to identify a mechanism capable of preventing the debilitating effects of academic stress on self-control and to come up with measures for its application to the Korean-specific context.

The present study empirically supported the claim that academic stress decreases Korean adolescents’ self-control. In order to protect the capacity for self-control among adolescents, policymakers should be attentive to adolescents’ voice arguing that the pressures regarding the university entrance examination is the primary factor causing academic distress (Moon & Jwa, 2008). Therefore, the Korean government should improve the current educational system, which focuses overly on the college scholastic ability test, by expanding services to enhance the potential of individual adolescents and to help them contribute in their lives (Weissberg et al., 2003).

Regardless of the implications, there are some limitations of the present study that should be addressed in future research. First, the present study hypothesized the causal relationship between academic stress and self-control according to the strength model of self-control (Baumeister et al., 2007). However, the current cross-sectional study practically examined the correlation between study variables. Considering the possibility of the reverse causation, future researchers should investigate the relationship more precisely.

Moreover, the moderating effect of self-esteem on the association between academic stress and the capacity for self-control was investigated without recognizing the time-varying effects of the study variables in this study. Thus, hypothesized relationships among the variables should be tested with study data in future research through a longitudinal approach.

On the basis of the present study’s findings, the self-esteem of Korean adolescents was identified as a preventive factor at an individual level. By adopting the ecological systems perspective, future research should attempt to understand how adolescents interact over time with the varied levels of environmental systems in which they are embedded in order to prevent themselves from the adverse outcomes of socio-psychological stress.

Lastly, the present study did not take into account the gender difference in the interactive mechanism of academic stress and self-esteem on the capacity for self-control in adolescents. Adolescent research is generally suggested to consider the particular developmental traits induced by the gender difference (Williams et al., 2007 as cited in Choi, 2009).