Daily variations in weather are known to be associated with variations in mood. However, little is known about the specific brain regions that instantiate weather-related mood changes. We used a data-driven approach and ASL perfusion fMRI to assess the neural substrates associated with weather-induced mood variability. The data-driven approach was conducted with mood ratings under various weather conditions (N = 464). Forward stepwise regression was conducted to develop a statistical model of mood as a function of weather conditions. The model results were used to calculate the mood-relevant weather index which served as the covariate in the regression analysis of the resting CBF (N = 42) measured by ASL perfusion fMRI under various weather conditions. The resting CBF activities in the left insula-prefrontal cortex and left superior parietal lobe were negatively correlated (corrected p<0.05) with the weather index, indicating that better mood-relevant weather conditions were associated with lower CBF in these regions within the brain’s emotional network. The present study represents a first step toward the investigation of the effect of natural environment on baseline human brain function, and suggests the feasibility of ASL perfusion fMRI for such study.

The influence of weather variability on mood is well recognized, both in popular culture as well as in scientific research. There is evidence that the weather (including day light) exerts an effect on mood in the normal range of daily mood fluctuations (Howarth & Hoffman, 1984; Parrott & Sabini, 1990; Persinger & Levesque, 1983; Sanders & Brizzolara, 1982), as well as in longer term mood disruptions seen in psychiatric conditions, especially in seasonal affective disorder (SAD; Partonen & Magnusson, 2001) and also in bipolar disorder (e.g., Shapira et al., 2004). Previous research has identified specific weather variables that influence mood, including humidity (Howarth & Hoffman, 1984; Sanders & Brizzolara, 1982), atmospheric pressure (Keller et al., 2005; Persinger & Levesque, 1983; Whitton, Kramer, & Eastwood, 1982), wind speed (Denissen et al., 2008), and temperature (Howarth & Hoffman, 1984; Keller et al.; Whitton et al., 1982).

In spite of years of research into the influence of weather variability on mood, it is still not known by what mechanism the weather exerts its effects. How do sunlight and a clear sky, for example, lead to good moods? Conversely, how do clouds and rain induce bad moods? One powerful way to begin to elucidate the mediators of weather-induced mood effects is to investigate the specific brain regions that are associated with weather-related mood variability. This line of investigation can help us to understand the mechanisms through which weather variability is “transduced” into mood variability and eventually develop possible treatments for weather-induced mood disorders. However, due to the limitations of lacking of baseline brain function quantification and poor sensitivity to low frequency signal for the widely used blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) contrast, current BOLD fMRI is not able to detect regional brain activities associated with slow mood variations which evolve over a long time, such as hours, days or even months.

In the present study, we combined a behavioral data-driven approach with a novel functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) technique—arterial spin labeled (ASL) perfusion fMRI—to explore the neural mechanisms underlying weather-related mood changes. Perfusion fMRI permits a noninvasive quantification of regional cerebral blood flow (CBF) by using labeled inflowing arterial protons as an endogenous tracer (Alsop & Detre, 1998); it provides excellent producibility over long time periods, reduced susceptibility artifact, and less variability across subjects (Aguirre et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2003a, 2003b, 2004), suggesting it is an ideal tool for imaging slow behavioral and emotional fluctuations that involve the function of deep brain structures.

In the current study, mood rating data under various weather conditions were collected from hundreds of people and a stepwise regression model was developed to reveal the mood-relevant weather conditions. The results of this model were used to calculate the mood-relevant weather index of scan days, which served as a covariate in the regression analysis of the resting CBF measured by ASL perfusion fMRI. We hypothesized that the neural substrates associated with weather-related mood variability would be revealed by the correlations between the mood-relevant weather index and baseline CBF changes. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to combine weather variability, mood, and perfusion fMRI to elucidate the neural correlates of weather-related mood variability.

2.1.1 A statistical model of mood

Moderately large samples are generally required to detect the effects of weather on mood, especially when the study uses a between-subjects design. It is difficult to generate samples this large in fMRI studies, and within-subjects designs would involve additional complications from needing to schedule sessions under at least two significantly different set of weather conditions for every subject. Therefore, we used stepwise regression to develop a statistical model of mood, based on a behavioral research study of participants’ mood ratings under various weather conditions. We used this model to determine the weather-related “mood index” for days on which other research participants had undergone baseline (task free) functional neural imaging scans. We then examined whether neural activity was significantly associated with the weather-related mood index on the day of each scan.

2.1.2 Mood ratings

We asked adults waiting at the main train station in Philadelphia, PA, to rate their moods on a 100 mm visual analog scale (VAS), making a single mark to indicate their current mood. The VAS was anchored with “Worse than usual” and “Better than usual” at the ends, and “Average” in the middle. We worded the anchors this way in order to control as much as possible for individual differences in mood that were unrelated to the current conditions, including weather. Various versions of the VAS have been used in clinical research and have been shown to be reliable and valid measures (for reviews see Ahearn, 1997; McCormack, Horne, & Sheather, 1988). A total of 464 subjects (57% female, mean age 39 years, range: 18-83) rated their moods under various weather conditions on 15 days from May 2003 to April 2004.

2.1.3 A stepwise regression model

We retrieved data from the National Weather Service Forecast Office (http:// www.erh.noaa.gov/er/box/dailystns.shtml) for weather variables on the 15 days that we collected mood ratings. The candidate weather variables were the amount of cloud cover, maximum, minimum, and average temperature, dew point, wind speed, amount of precipitation, whether rain or fog were present, maximum and minimum humidity, and atmospheric pressure. We entered these weather variables into a forward stepwise regression model with mood as the dependent variable. Stepwise regression builds a best-fitting statistical model based on a set of candidate predictor variables. In forward stepwise regression the variables are entered one at a time, beginning with the best predictor variable, adding the second best predictor given that the first predictor is already in the model, and ending when the addition of any more variables would not significantly increase the fit of the model—that is, the percent of mood variance for which the model accounts.

2.2.1 Imaging protocol

Written informed consent was obtained prior to all studies according to an Institutional Review Board approval from the University of Pennsylvania. A continuous ASL technique was conducted on a Siemens 3.0T Trio wholebody scanner (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany), using a standard Transmit/ Receive head coil for perfusion fMRI scans. Arterial spin labeling was implemented with a 0.16G/cm gradient and 22.5 mG RF irradiation applied 8 cm beneath the center of the acquired slices. Control pulse was an amplitude modulated version of the labeling pulse based on a sinusoid function (Wang et al., 2005). The tagging/control duration was 1.6s. Interleaved images with and without labeling were acquired using a gradient echo echoplanar imaging (EPI) sequence. A delay of 0.8 sec was inserted between the end of the labeling pulse and image acquisition to reduce transit artifact. Acquisition parameters were: FOV = 22 cm, matrix = 64 × 64, TR = 3 sec, TE = 17 ms, flip angle = 90°. Twelve slices (6 mm thickness with 1.5 mm gap) were acquired from inferior to superior in a sequential order. Highresolution anatomic images were obtained by a 3D MPRAGE sequence with TR = 1620 ms, TI = 950ms, TE = 3 ms, flip angle = 15°, 160 contiguous slices of 1.0 mm thickness, FOV = 192 × 256 mm2, matrix = 192 × 256.

2.2.2 Imaging data acquisition and analysis

The resting perfusion images of 42 healthy subjects (24 female, mean age 27 years, range 19-44 years) were acquired when subjects were looking at a fixation for about 3 to 6 min without any other cognitive task. These perfusion data were scanned as the baseline conditions of four ASL fMRI experiments from April 2004 to March 2005. Functional image processing and analysis were carried out primarily with the Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM99 and SPM2, Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, UK implemented in Matlab 5, Math Works, Natick, MA). For each subject, functional images were realigned to correct head motion, coregistered with the anatomical image, and spatially smoothed using a Gaussian filter with a full-width at half maximum (FWHM) of 10 mm. Perfusion weighted image series were generated by pair-wise subtraction of the label and control images, followed by conversion to an absolute CBF image series based on a single compartment CASL perfusion model (Wang et al., 2005). CBF images were normalized to a 2 × 2 × 2 mm3 Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template using bilinear interpolation. One mean CBF image was generated for each individual subject and entered into the voxel-wise multiple-regression analysis using the general linear model (GLM). The weather index resulting from the regression model was used as the covariate of interest in the GLM analysis. Two additional nuisance covariates were included in the GLM model to account for age and gender differences. To explore the brain regions associated with the weather-induced mood variability, positive and negative correlations with the mood index were defined in the GLM analysis. Areas of significant activation were identified for the false discovery rate (FDR; Genovese et al., 2002) corrected P value smaller than 0.05 and cluster size larger than 30 voxels (voxel size 2 × 2 × 2 mm3). Moreover, to validate the relationship between the weather index and the CBF changes, the quantitative CBF (after normalizing the global CBF to 50 ml/100g/min) of the peak activation voxels (sphere with 5 mm radius) were read out from the mean CBF image for each subject, and directly correlated with the weather index. Finally, in order to further confirm the specificity of the observed association between regional CBF and the weather index, two additional control analyses were conducted. In one analysis, we generated a series of random values within the range of the weather index, and used it to replace the weather-index for the voxel-wise multiple-regression analysis. In another analysis, we picked, a single weather variable (e.g., raining) and used it to replace the weather-index for the voxel-wise multiple-regression analysis. Both analyses also included age and gender as nuisance covariates, respectively.

3.1 A stepwise regression model

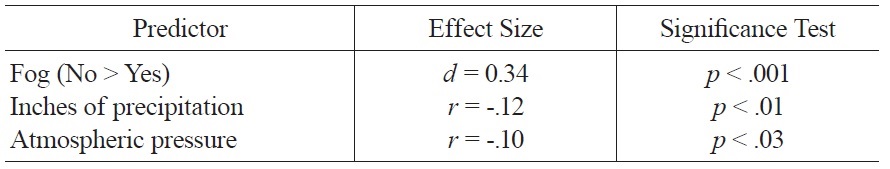

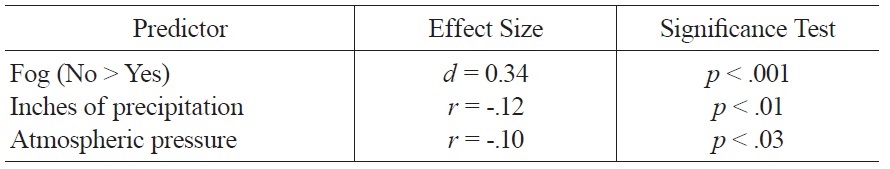

The regression model of weather variables accounted for 8% of the variance in mood ratings and included the following variables: amount of precipitation, fog, and atmospheric pressure. Better mood was associated with less precipitation, absence of fog, and lower atmospheric pressure; zero-order associations between these variables and mood are summarized in Table 1.

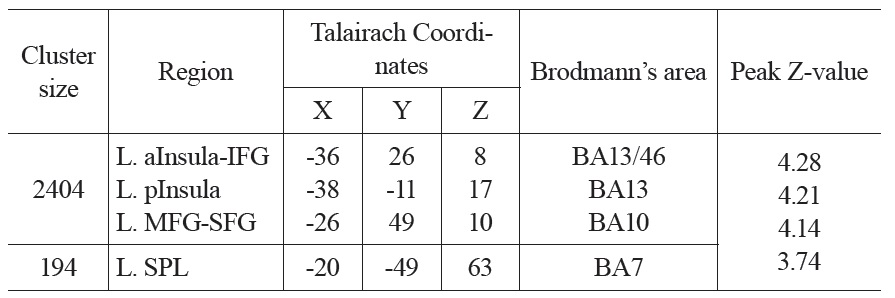

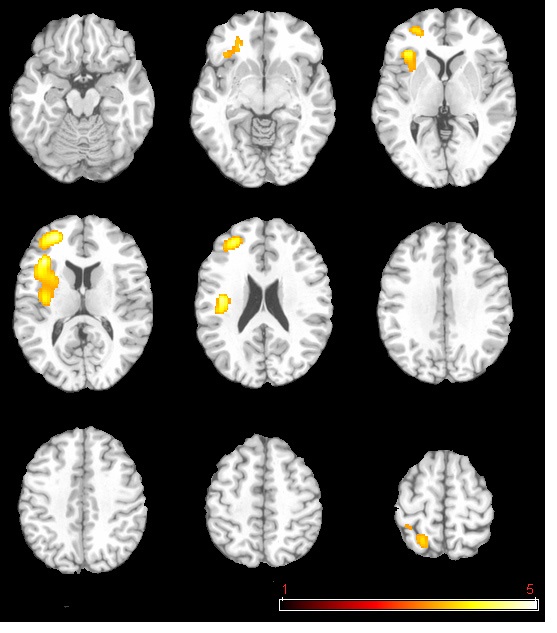

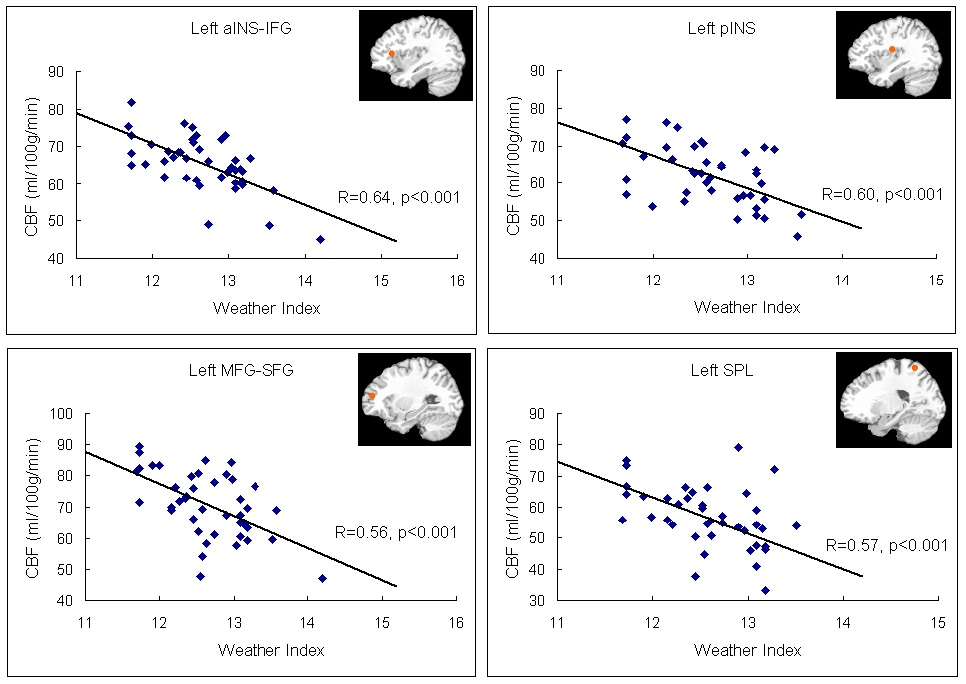

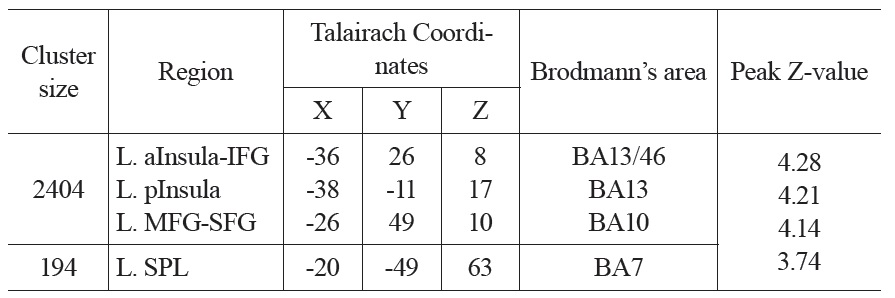

The neural activation results from the regression analysis are illustrated in Figure 1 and summarized in Table 2. Among the two correlations, only the negative correlation of the weather index-induced significant activationssurvived the threshold of FDR corrected p < 0.05, which include activations in the left anterior insula-inferior prefrontal gyrus (aINS-IFG), the left posterior insula (pINS), left middle-superior frontal gyrus (MFG-SFG) and left superior parietal lobe (SPL). However, the control analyses with a single weather variable or random variable did not find any brain regions showing significant correlations with these variables, supporting the specificity of the observed association between regional CBF and weather index. The direct correlations between the forward weather-induced mood variability index and the quantitative CBF signal intensities (in terms of ml of blood/100 g of tissue/minute) within these peak activation voxels are illustrated in Figure 2. Significant negative correlations were demonstrated in all peak activation voxels (all R > 0.5, p < 0.001).

[Table 1.] Significant Zero Order Associations of Weather Variables and Mood.

Significant Zero Order Associations of Weather Variables and Mood.

The brain activations associated with weather-induced mood variability (FDR corrected p < 0.05, cluster size > 30 voxels).

We used a novel technique to investigate the brain regions that show differential baseline (task free) activity as a function of weather-related mood variability. We first constructed a statistical model for mood-relevant weather conditions; the model comprised the variables of atmospheric pressure, fog, and precipitation. These variables had relatively small effects on mood, which is consistent with earlier reports on the weather-mood association. For example, Denissen et al. (2008) reported significant associations between negative affect and temperature, wind speed, and sunlight; however, none of the regression weights was larger than approximately 0.07. Thus, the effects of weather conditions on mood appear to be relatively small.

We found two clusters of neural activity that were significantly associated with our weather-related mood index: one in the anterior and posterior insula, extending into the inferior, middle, and superior frontal gyrus, and one in the superior parietal lobe. Each of these regions showed significant negative correlations with the weather-related mood index; that is, as mood related to weather conditions worsened, activity in these regions increased.

Studies so far have found consistently that the anterior insula is involved in emotion-related processes. For example, Etkin and Wager (2007) found in their meta-analysis that the insula played a key role in a fear network that was activated across anxiety disorders and in laboratory fear conditioning in humans. As such, the increased insula activity under poor weather conditions may reflect an increase in negative affect on those days. However, there is evidence that the insula is involved in affective experience across emotional valence; Phan and colleagues (2002) meta-analyzed emotion activation studies and found that the insula was activated consistently across emotion categories (e.g., fear, sadness, happiness). Indeed, a large number of studies have implicated the insula in the awareness of various internal states, including pain (e.g., Kong et al., 2006), gastric distention (Stephan et al., 2003), thirst (Denton et al., 1999), and heartbeat (Critchley et al., 2004; for a review see Craig, 2009; for an evolutionary perspective on the role of the insula, see Craig, 2011). Thus, in the present study the correlation of mood-related weather with insula activity may reflect the subjective awareness of increasingly negative mood states in response to poor weather conditions (e.g., rain).

The current findings are also consistent with existing research on the role of the insula in frank depression. There is evidence that anterior insula activity is elevated in patients suffering from depression (e.g., Beauregard et al., 2006) and decreases after successful treatment of major depressive disorder (e.g., Brody et al., 2001; Mayberg et al., 1999). Thus, the current findings suggest that the insula may be a neural substrate by which changes in weather affect longer term mood states, such as seasonal affective disorder. More research is necessary to test this hypothesis.

The superior parietal lobe also has been implicated in previous studies of emotion. For example, Beauregard et al. (2001) found that activity in this region (Brodmann Area 7) was significantly activated during the attempted inhibition of positive affect. Similarly, Goldin et al. (2008) found activation of the superior parietal lobe when subjects viewed negative film clips; Goldin and Gross (2010) reported significant activation of this region when subjects with social phobia reacted to negative self-beliefs. However, the superior parietal lobe is not considered primarily an affective neural region, but is associated more commonly with visual attention (e.g., Corbetta et al., 1995). More work remains to be done to better understand the role of the superior parietal cortex in affective states.

The current findings stand in contrast to theories about the right lateralization of negative affect (e.g., Davidson, Jackson, & Kalin, 2000) given that in the present study negative mood-inducing weather was associated with greater activity in regions of the left hemisphere. However, numerous studies have found significant associations between the left insula and negative emotion. Indeed, a meta-analysis by Wager et al. (2003) found that withdrawal-related emotions (e.g., fear) were more likely to activate left than right insula. Therefore, the current findings are consistent with existing reports showing the involvement of the left hemisphere in negative emotional states.

This study has several limitations. We used an indirect measure of weather-related mood for subjects who underwent baseline perfusion scans; thus, it cannot be known the extent to which the mood index captured the weather-related mood of scanned subjects. Alternative study designs could be used to address this question, which is central to the present study. One option would be to assess the mood of subjects scanned under different weather conditions and determine which weather variables are associated with mood for these subjects; one then could construct a statistical model of weather-related mood for those subjects which could be used to predict neural activity. The drawback of this approach is that it would require a very large number of scanned subjects in order to isolate the weather variability associated with mood due to the relatively small percent of variance in mood captured by weather variables (8% in the regression model used in our analyses). Alternatively, one could examine directly the association between weather variables and neural activity, which would remove an intervening step between weather and neural activity (weather → neural activity vs. weather → mood → neural activity). The disadvantage of this approach is that it would not isolate the effect of weather variables on mood, as opposed to the effect of weather on other variables (e.g., cognitive variables). Furthermore, it would not be clear with this approach which of the many candidate weather variables (e.g., humidity, temperature, precipitation, barometric pressure) were the mood-relevant ones to include as predictors of neural activity. Finally, participants could be scanned on at least two different occasions under different weather conditions. While the within-subjects aspects of this design would represent a strength in that each participant would serve as his/her own control, it would also introduce significant logistical challenges. Given the drawbacks associated with alternative designs, it appears that the approach used in the present study was a reasonable first step in this area of investigation.

An additional limitation of the present study is the use of a single-item measure of mood—a visual analog scale (VAS)—in the assessment of mood-related weather variables.. While the VAS has been shown to have satisfactory psychometric properties (e.g., McCormack et al., 1988), it may be beneficial to make more fine-grained examinations of mood. Other studies in this domain have used more comprehensive assessments of mood in the context of weather. Dennisen et al. (2008), for example, used the PANAS (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988), which comprises separate scales for positive and negative affect. Results from Dennisen et al. reveal that it may be important to distinguish among specific aspects of mood given their finding of an association between weather and negative, but not positive, mood. It will be interesting in future studies to determine whether neural activations like those found in the present study are driven by the positive mood effects of good weather, by the negative mood effects of bad weather, or both.

We did not record the time of day in the current study, although all data collection was done in the mid-afternoon to ensure exposure to potentially mood-relevant weather effects. Future work could include time of day as a covariate in the model of weather-related mood. Finally, we were unable to test the effects of weather variables on mood separately by season. Future work should examine the influence of weather on mood at different times of the year; for example, one might investigate whether sunny days have a relatively greater effect on mood in the winter versus in the summer, given the shorter supply of sunlight in winter months.

In summary, the current study represents a first step toward understanding the effects of variability in the natural environment on baseline human brain function and suggests the feasibility of ASL perfusion fMRI in this endeavor. Additional studies are required to replicate the current findings. The use of larger samples would allow for the testing of additional variables and for the examination of interesting interactions between weather and psychological variables (e.g., measures of personality) on mood and brain function.