Yŏnae was the first word in modern vocabulary to publicly highlight the feelings between men and women in Korea. Yŏnae was first used as an independent word during the early colonial era, and this usage was instrumental in bringing about a series of social and cultural changes. These included a restructuring of the family system, an increased attention to the human inner self, a new interest in modern literature and art, and growth of modern urban culture. The concept yŏnae is remarkable for its ability to engender contention, and a large number of studies have therefore been conducted on this topic.2 Many researchers studied the meaning of yŏnae through its relationship with a wide variety of elements: the family system, discourses on marriage, Darwinism and eugenics, the new institution of education, the establishment of modern literature, early marriage and romance between a married man and a kisaeng (female entertainer), the conflict between traditional and modern worldviews, and a modern generation of women.3 These works clearly indicate that an academic consensus has already been reached on the significance of yŏnae as an innovative concept.

These earlier studies on yŏnae, however, were conducted in a rather desultory fashion. Many started from the modern meanings of the concept yŏnae, using these to delve into its impact on literature and art, but such studies rarely focused on the historical process of how the concept itself evolved.4 Due to the lack of comprehensive and historical studies on the concept, some fallacies have arisen in specific discussions on yŏnae, and there are inconsistencies between the various accounts. For instance, some studies found that yŏnae was a modern concept because it recognized the spirituality of the male-female relationship, and others because it emphasized the unity between body and soul; some studies interpreted ‘chayu yŏnae’ (free love) as love freely chosen by both parties outside of parental control, while others viewed ‘chayu yŏnae ’ as free-spirited love allowing a frequent change of partners; some studies interpreted ‘sinsŏnghan yŏnae’ ’ (sacred love) as pure platonic love without any physical encounters, and others identified ‘sinsŏnghan yŏnae’ with modern yŏnae as such. Obviously, these earlier studies have employed diverse and even contradictory interpretations of the concept yŏnae.

Such differences are commonplace, given that studies often overlook the fact that a single word can be understood differently by different parties. The way that meanings evolve over time is also often neglected: the later meaning may be greatly altered, only partially overlapping with, or even conflicting with earlier meanings. For all these reasons, the concept of yŏnae needs to be studied from the perspective of conceptual history. This study intends to track the historical process of how the concept was formed, and how it evolved, during the period between the early modern era and the late colonial era. Theoretical discussions on or direct public mentions of the topic of yŏnae are used, rather than fictional writings or books about being in love, to track down the primary semantic changes of the signifier ‘yŏnae.’ Tracking how the concept evolved over time is useful primarily in limiting the confusion between the various understandings of the concept, and also in helping to establish a historical standard for an interpretation of the evolving concept. Moreover, studying the history of the concept yŏnae enables us to look back at these earlier times from the perspective of the correlations between thoughts about love and the practice of love, which will then help us examine the meanings of sexuality, love, and marriage during this period.

2The representative research would be as follows: Choe Hye-sil (2000); Kim Dong-sik (2001); Kwŏn Podŭrae (2003); Chŏng Hye-yŏng (2006); Kim Chiyoung (2007). 3The pioneering researches would be as follows: Chŏng Hye-yŏng (1999) ; Kwŏn Podŭrae (2001); Kim Dong-sik (2001); Ku In-mo (2002); Lee Kyŏng-hun (2003). 4Research by Kim Chiyoung (2004)and Kwŏn Podŭrae (2005) has dealt with the meaning of the vocabulary yŏnae and researched the relationship between the vocabulary and other social elements surrounding the word. However, the research did not illuminate the whole meaning changing process of the word yŏnae in the colonial period, since it mainly focused on the Korean enlightenment period. On the other hand, Sŏ Chi-yŏng (2008) studied the perceptional differentiation of love during the colonial period from the perspective of feminism and examined how the foreign theory of love was accepted and refracted in Korea, which is different from the views of this article focusing on the changing process of the concept.

The word yŏnae (love), referring to love between a man and a woman, originated from the English word ‘love.’ The concept had first been introduced in Korea at the end of the 1800s but it was not until the late 1910s that it became a generalized concept. Of course, sarang (love) had existed even before the concept yŏnae was fully formed, but the way that love had been viewed and practiced at that time was different from the way it was practiced after yŏnae was conceptualized.

The Chinese character most equivalent to the concept of ‘love’ from which yŏnae originated is ‘ 愛 ’ (affection). However, in East Asian society with its dominant ideology of Confucianism, ‘ 愛 ’ was perceived as something very different from yŏnae, let alone from ‘love’ as currently understood. The Confucian understanding of natural and biological emotions is characterized by Mencius’ phrase: “Ch’inch’ininminaemul” (親親仁民愛物).5 Mencius means that we should be devoted to our parents and family (ch’in, 親), should be generous to other people, and should love the world around us. As the saying indicated, Confucianists considered filial piety (hyo, 孝) as being the fundamental principle underlying all human virtue, ranked benevolence (in, 仁) as the core, and viewed affection as the next most important thing. ‘Affection’ was one of seven feelings considered to comprise the basic human emotions, and, like the other six elements (happiness, anger, sorrow, joy, hate, and desire), it had to work within the framework of the four moral values: benevolence, righteousness, propriety and wisdom (in ŭi ye ji, 仁義禮智).

There were different degrees of ‘affection,’ as can be inferred from the teachings of Mencius: “If I care for another’s parents and children in the same way as I do for my own parents and children, then I have the whole world in the palm of my hand,”6 Confucianists viewed love as a feeling that could be different depending on to whom the love was directed.7 Although ‘affection’ was recognized as a basic human desire, different types of love were imagined, had to be controlled, and set within a universal ethical framework. In Confucianism, the key concept of human virtue was benevolence, which leads to a merging of the universe and things. ‘Affection’ (愛) was significant only insofar as it contributed to benevolence by conforming to the principle of nature. Thus, affection was seen as just an intermediate feeling on the path towards benevolence.8

In this ideological system, which regarded filial piety as fundamental and benevolence as the preeminent virtue, the love between men and women was considered inconsequential. Accordingly, the words used to denote the feelings arising in male-female relationships could develop no further. In a cultural environment where people felt obliged to guard against expressing immoderate or excessive emotions, the relationship between men and women was generally not spoken about. Such relationships were described by Chinese characters like 愛 (affection), 樂 (nak, joy), 情 (chŏng, emotional ties among friends and family members), 色 (saek, lust), 寵 (ch’ong, favor), 思 (sa, think), and 好 (ho, like); and by words like 愛樂 (aerak, love and joy), 愛顧 (aech’ong, care with love), 相思 (sangsa, mutual affection), 戀慕 (yŏnmo, affection) and 愛情 (aejŏng, love); but none of these terms was established as an independent concept to indicate feelings arising in male-female relationships.

Korea, China, and Japan shared the same Chinese cultural and semantic sphere, taking a similar attitude toward love between men and women, which was not defined as an independent concept but was used differently depending on the broader semantic field of words like 愛 (affection), 情 (emotional ties), 樂 (joy) and 色 (lust). In China and Japan, words of Western origin, like ‘love,’ ‘amore,’ ‘liefde,’ etc., were translated as 愛 (affection), 好 (like), 愛惜 (aesŏk, care), 戀愛 (love), 愛情 (affection), 寵 (favor), 仁 (generous love), 寵愛 (ch’ongae, dear favor), 敬愛 (kyŏngae, respect), 戀神 (yŏnsin, adoration), 鐘愛 (chongae, deep affection), and 好愛 (hoae, dear love).

The missionary Medhurst used 愛 (affection), 好 (like), 愛惜 (love/care) and 戀愛 (love) as translations for the verb ‘to love’ in the English-Chinese Dictionary he published in 1847–1848. Subsequently, in a Dutch-Japanese Dictionary (1855– 1858), a French-Japanese Dictionary (1864), and an English-Chinese Dictionary (1862), diverse combinations of Chinese characters were used to translate ‘love’, ‘amore’, and “liefde,” such as 戀 (yearning), 愛 (affection), 戀神 (adoration), 寵愛 (dear favor), and 財寶 (chaebo, precious things).9 It was not until the 1890s, when a Japanese magazine Zyogaku zasshi [女學雜誌] portrayed yŏnae as a key theme, that the word ‘yŏnae (love)” stood out from other Chinese words to become dominant. In October 1890, Iwamoto Yoshiharu, the editor-in-chief of Zyogaku zasshi, gave a rave review of the translation of a novel entitled Lily of the Valley for its use of the word 戀愛 (yŏnae) to translate ‘pure and true’ love originating somewhere ‘deep down in the soul’, instead of using the “vulgar words (戀 : yearning, 色 : lust) that conjure up filthy connotations.” His commentary proved a watershed, after which magazines used the word ‘ 戀愛’ (yŏnae) more widely to describe exotic love such as that of medieval knights. The word yŏnae ascribed a lofty perspective to heterosexual love, seeing it in a ‘spiritual’ light, and moving beyond the traditional interpretation, which associates male-female relationships with physical intimacy. After this, yŏnae started to gain popularity in Japan during the mid-late Meiji era, as a word that granted an elevated moral character to the relationship between men and women.10

In Korea, the modern meaning of yŏnae was first used in Sŏyu kyŏnmun [Observations on travels in the West], published by Yu Kil-chun in 1895.11 The book, a systematic description of the West’s politics, public administration, cultures and customs, first used the concept yŏnae in chapter 15, as a “procedure for getting married,” when discussing motives of men that propose marriage:

The reason Yu Kil-chun used the word yŏnae, which had hardly been used before, seems to be the Japanese influence: he had passed through Japan en route to the U.S. But in Sŏyu kyŏnmun, yŏnae was not used as something noble and spiritual, as it had been in Zyogaku zasshi. Indeed, Yu Kil-chun found Western culture, where the parties to a marriage directly discussed the matter without an arrangement by their parents or a matchmaker, extraordinarily odd. In the beginning of the chapter, he stated: “the way of proposing marriage in the West is very different from our customs and manners here, so there is much room for criticism. However, that is another country’s culture and customs, so I would leave it at that. (…) All I am doing here is simply putting the way it is on record.”13 As may be inferred from the quotes from his book, Yu Kil-chun used the word yŏnae with a value-neutral tone. In all, he used the word yŏnae five times, as a verb, and with a similar meaning to the one that it is given in Medhurst’s Dictionary, which clearly implies that yŏnae as he meant it, was rather close to the usage that preceded the Meiji era of Japan.

After Sŏyu kyŏnmun was published, the word yŏnae was not used much in Korea until the 1910s, except for a few cases: a news article describing ‘a dispute over yŏnae’ that eventually led to a shooting incident at a motel owned by a white man;14 a novel that draws a parallel between yŏnae and thoughts/behaviors within the sphere of the right to freedom;15 and a commentary that mentions yŏnae in the context of the agony of youth.16 All in all, the word yŏnae in the 1900s was used only rarely and in a fragmentary manner. Thus, the concept was not able to build a consistent semantic field.17

The concept yŏnae only started to emerge as the focus of social attention after Japan’s annexation of Korea, when marriage reform proposals, which had been around since the end of the 1890s, were back in favor. After Korea’s initial acquaintance with Western marriage systems, via Sŏyu kyŏnmun, many reformminded intellectuals who opposed customs, like early marriage or forced marriage, emphasized the rationality of the Western-style system of marriage, where both parties were able to respect each other’s decisions. As these radical theories of marriage came back into the mainstream during the mid-late 1910s, the word yŏnae started to be more widely used. In fact, the word yŏnae emerged as being rather closely related to marriage, for example: “there are two kinds of happiness which can be gained from marriage; yŏnae & family,”18 or in an editorial that stressed “putting an end to forced yŏnae and encouraging free yŏnae”19 as a prerequisite for ideological reform.

During the 1910s, proponents of radical marriage theories gathered strength, as these ideas became linked to theories of social Darwinism. Enlightened intellectuals, such as Yi Kwang-su and Song Chin-u, were fiercely critical of the traditional custom of early marriage, describing it as a manifestation of a “food and lust-oriented barbaric philosophy of life,” and clearly distinguished civilized yŏnae from “animal or primitive love.”20 According to them, “yŏnae evolving” from the antipode of primitive love should have both “traction of passionate emotion and smart cool intellect in parallel.”21 In other words, a yŏnae-based civilized marriage should have modern elements that distinguish it from primitive love.

The word yŏnae, which brought ‘emotion’ and ‘intellect’ into its semantic field as requirements for marriage, turned the spotlight upon inner emotional issues, within the context of free marriage, which emphasized breaking free from parental control. Vigorous new ideas were put forward: “yŏnae should precede marriage just like clouds precede rain,”22 and “only unbreakable yŏnae can make a rightfully-married couple.”23 Thus, yŏnae not only alluded to breaking free from forced marriage but was also stipulated as a type of special independent emotional prerequisite for marriage. This was a definitive event, when the passion between a man and a woman, previously considered “something not fit to be mentioned by a man of virtue” was granted official status as a subject of discourse.24

As this new conceptual space was opened up by yŏnae, people were able to envision a new intellectual and emotional framework for the feelings between men and women, allowing imaginative ideas about living a civilized life with a noble mind to arise, and these naturally rushed into the space made newly available. Commentaries that justified love elevated yŏnae to a higher level, so that it became a noble value that “has sacred and noble tastes in it.”25 The concept yŏnae was made mysterious, as a transcendent “wonder of the universe,” which connects lovers be they rich or poor, of high or low birth, educated or uneducated, and also bridges geographical separation.26 The very existence of such a noble emotion provided a foundation for the formation of new human values that transcended long-established patterns of social status.

yŏnae, a concept which fundamentally underlies the manner in which young people conduct themselves, became a powerful structure enabling young intellectuals to differentiate themselves from the older generation, and to position themselves as leaders ushering in a new civilization.27 yŏnae, a modern concept, which acknowledges the peculiar importance of personal feelings, granted a recognized official value to the emotions felt between men and women. It also encouraged a growth in self-reflection about personality and guided the formation of a new and modern relational structure.

5Mencius, “Fulfilling Heart, the first,” Mencius. 6Mencius, “King Yanghae, the first,” Mencius. 7Thus Moze’s theory of ‘loving each other’ (C. jianxiangae, K. kyŏmsangae, 兼相愛) was refuted by Confucianism in that the theory was equivalent to denying one’s own father. Kwŏn Podŭrae (2005) examined the concept ‘ 愛, ’ with the perspective of its relationship with Confucian ideology, according to different sources. 8See Kwŏn Podŭrae (2005). 9Refer to Yanabu Akira, Translated by Sŏ Hye-yŏng (2003). 10Ibid. 11Sŏyu kyŏnmun is the first case of using the modern vocabulary item yŏnae. Before this article, the word ‘yŏnae’ was primarily thought to have first appeared in the adapted fiction Ssangongnu in 1913. After Sŏyu kyŏnmun was published, content similar to the above appeared in arguments on reformation of the institution of marriage in the newspaper Tongnip sinmun, but interestingly and ironically, the word yŏnae did not show up in the revived articles. 12Yu Kil-chun, Sŏyu kyŏnmun [Observations on travels in the West]. 1895. 13Ibid. 14“Chŏgyŏk sonyŏn” [Shooting boy], Sinhan’gukpo [New Korea daily], March 8, 1910. 15Mongmong (1909), p. 29. 16Kim Ha-gu (1909), p. 37. 17The usage of the signifier yŏnae in the 1900s was noted earlier in Kwŏn Podŭrae (2005). 18Yi Kwang-su (1917), p. 29. 19Song Chin-u (1915), p. 5. 20Yi Kwang-su (1961), p. 501. 21Yi Kwang-su (1917), p. 31. 22Ibid. 23“Kajŏng kwa honin” [Home and marriage],” Kwanak sinmun, Mar. 8, 1914. 24Concerning the accommodation of yŏnae in the late 1910s, see Kim Chiyoung (2007), Kwŏn Podŭrae (2003), Kim Dong-sik (2001), and Chŏng Hye-yŏng (1999). 25Cho Il-che, Ssangongnu, (Seoul: Pokŭpsŏgwŏn, 1913), p. 13. 26Song Chin-u, Op. cit., pp. 5–6. 27Refer to Kim Chiyoung (2007), Kwŏn Podŭrae (2003), and Kim Tong-sik (2001).

yŏnae, after building up an increasing number of practical usages from the late 1910s, really took off in the 1920s. Free marriage became a matter of common sense among intellectuals. Following the slogan of “evil practices should be eliminated and marriage should be based on yŏnae,”28 news articles encouraging dating were frequently published in newspapers and magazines. Young people, by insisting that “genuine marriage requires an amicable understanding and passionate yŏnae between two people,”29 often came into conflict with their parents’ generation. Among the youth of the day, an ever-increasing number openly supported the central importance of ‘yŏnae.’ Although there was some criticism along the lines that a wrong notion of yŏnae caused family disruption and harm to society,30 young people readily endorsed sentiments which valued yŏnae highly, such as “yŏnae is something sacred,”31 and the idea that “yŏnae is the manifestation of one’s whole personality and noble moral soul.”32 The notion that “‘yŏnae is something sacred’ was already becoming an established fact.”33 For a few years before and after 1920, Korea enjoyed an unprecedented golden age of love.

This exciting new fashion for yŏnae did not arise in isolation, however. The golden age of love in Korea blossomed at just the time that fresh new theories of love were flooding in from Japan and the West. Both the use of the word yŏnae, and also these imported theories of love, gave rise to a general dissatisfaction among young people with the traditional culture of forced marriage that had prevailed during the Chosŏn period, resulting in a transformation of traditional perceptions of love and marriage.

Ellen Key, a Swedish feminist and proponent of child-centered education, was the first theoretician to raise awareness of yŏnae among the youth in colonial Korea. Her writings on love, marriage and motherhood, were translated and introduced in Japan during the Taisho era.34 In Korea, an article entitled “A Leading Activist for Feminism, Ellen Key,” by No Cha-yŏng, published in the February 1921 issue of Kaebyŏk (The dawn), was the first to introduce Ellen Key’s writing. A series of similar articles continued to be disseminated in Korea until the 1940s. A key element of Ellen Key’s theory of ‘love and marriage’ was that personal happiness was the basis for tribal happiness. According to Ellen Key, whose thinking was rooted in social Darwinism and eugenics, love functions as a link between personal and tribal happiness, and is a prerequisite for creating a more complete and fulfilled society.35 She believed that human beings have elevated their instincts into passion, and passion into love in the process of evolution. She said that the desire for the opposite sex could progress to become a great love when it is combined with a desire for the other’s soul. She also believed that such great love enables the development of whole human beings in which emotion and soul, passion and obligation, self-assertion and dedication are all blended together.36 By stressing that ‘love’ is a prerequisite for both tribal and personal happiness, she integrated two seemingly incompatible elements— personal love and public development—into a single issue.

Ellen Key’s concepts built a theoretical foundation for love to be seen as a higher-level mental phenomenon, replacing the view of it as a simple and unsophisticated feeling aligned with physical lust.

With her Darwinian perspective on human nature and culture, she took a scientific approach by starting off the discussion of love with sexual desire, which is ultimately elevated into fully civilized love, becoming truly ethical as a result of the refinement and purification of primary instincts. These pioneering ideas provided the East Asian cultural sphere of Korea, China and Japan with a logical foundation for the theory of ‘love for love’s sake,’ which was prominently developed in Kuriyagawa Hakuson’s book Modern Views on Renai (yŏnae).

This seminal work, published in 1922, encompasses the author’s understanding of Western literature, psychoanalytic (Freudian) knowledge, and an analysis of Ellen Key’s writing. It became a best seller in Japan, and was also enthusiastically received in China and Korea. The gist of the book can be summarized as follows: 1) to champion a theory of ‘love for love’s sake,’ which considers yŏnae as the highest value of all; 2) to highly value yŏnae as the outcome of sublimated sexual desire; 3) to establish a thought of yŏnae which draws body and soul together; 4) to strongly endorse monogamy.

Kuriyagawa accepted and further developed Ellen Key’s theories, viewing yŏnae as the outcome of ‘sublimated’ sexual desires and as the highest morality and art,37 and expressing the perspective on yŏnae as the unity of body and soul, asserting that only the unity of the two sexes can make a complete human being.38 Besides all this, Kuriyagawa added his own uniquely romantic color and flavor in laying the groundwork for his theory of ‘love for love’s sake.’

The book starts with a chapter titled ‘Love is Best’ and ends with a verse of Browning’s: “virtue on earth in life is a kiss from a girl.”39 It portrays yŏnae as an absolute value, saying the “eternal and timeless power of life dwells in yŏnae, which should be the culmination of burning passion, inspiration, adoration, and desire for humans.”40 The way the book is structured, and the way it delivers its messages, clearly demonstrates the author’s unique romantic perspective on yŏnae, which permeates his florid arguments. The philosophy of romanticism, which contends that sources of life and universal truth are hidden within one’s inner self, underpinned his rhetorical embellishment in identifying yŏnae as an ‘eternal’ value, and as the ultimate manifestation of human passion.

Kuriyagawa’s argument, however, did not progress beyond ‘love for love’s sake’ to laissez faire love. Taking a rather critical approach to Ibsen’s A Doll’s House which was highly acclaimed by advocates of free-marriage, Kuriyagawa argued that “denying an ego is the affirmation of a bigger ego”41 , and when overcoming all the difficulties in marriage, instead of leaving home like Nora in A Doll’s House, “you can have a genuine loving relationship and lead a life of freedom which offers genuine liberation of the ego”42 . Insisting “genuine yŏnae is to find you in your partner, and your partner in you,” he also asserted genuine freedom “that moves away from the ego and opens up to the higher self ” as an “absolute state that can only be reached by self-sacrifice and self-renunciation.”43 The overall tone of Kuriyagawa’s arguments in his book provides a foundation for his theory of ‘yŏnae = civilized personality,’ which regards yŏnae as a yardstick of personality and as “a symphony of the two genders that enriches and completes oneself as a human being”44 .

Kuriyagawa asserted that such kind of love vanishing after marriage is nothing more than a game, and does not represent “a desire for genuine unity in a genuine spiritual life”45 . Kuriyagawa viewed love and marriage as something inseparable, and conceptualized yŏnae as a manifestation of personality and the sign of a mature personality. This means that yŏnae, referring to civilized love, is more than just the feelings between a man and a woman. Rather, it is a manifestation of a modern ego, indicative of a civilized personality, and the theoretical ground that helps to create and maintain a modern family.

Kuriyagawa’s theories on yŏnae were fueled by the raging passion for yŏnae in the early 1920s, and had a huge influence on young people of colonial Korea. In 1925, The journal Chosŏn mundan (Chosŏn literary circles) published a special edition entitled “Scholars’ views on yŏnae” [Chega-ŭi yŏnae’gwan],” and the same articles were republished the following year in a book entitled Chosŏn Writers’ Views on yŏnae [Chosŏn munsa ŭi yŏnae’gwan]. The book reflects the prevailing vision of the day, depicting young writers’ views on yŏnae in a very direct narrative style.

Key and Kuriyagawa had an overwhelming influence on this book. For instance, it is filled with Kuriyagawa-style color, such as “yŏnae is a lifelong demand,”46 “yŏnae is sacred, and is the biggest, most genuine, and most beautiful thing in human life,”47 all of which have elements of Kuriyagawa’s ‘love for love’s sake’ reflected in them. The book also shows literary embellishments in the style of Kuriyagawa, which are synthesized with Key’s evolutionary theory. Examples include: “yŏnae is what poetizes sexual desires,”48 and “yŏnae is what allows two personalities with different sexes to connect with each other—and a symphony of the two genders striving to refresh, fulfill, and complete themselves as human beings through a mutual connection.”49

Like Kuriyagawa’s logic, yŏnae was connected with marriage for the young people of colonial Korea. The predominant discourse of the period is seen in phrases like “yŏnae is that which culminates in marriage”50 and “sacred yŏnae always has a commitment to marriage in its plan... yŏnae without marriage is nothing more than the play of a libertine.”51 The theories of Ellen Key also wielded significant influence, asserting the unity of body and soul: “Yŏnae undeniably has two aspects; spiritual and physical. A spiritual yŏnae cannot be reached without physical yŏnae, there would be no physical yŏnae without the spiritual one.”52

Kuriyawaga’s argument that ‘the state of genuine unity in a genuine spiritual life can only be reached while “marriage” is being maintained through mutual dedication’ was later debased, however, to become the equation ‘yŏnae = civilized personality = self-completion = self-sacrifice,’ which ‘omits’ the element of marriage.

His view of yŏnae as a path to self-discovery had its exponents: “yŏnae is a desire to save and complete yourself through coupling with the opposite gender,”53 or: “The joy you feel when finding yourself in your partner! When the joy becomes greater, that is the stage of sacred yŏnae. From that point on, yŏnae evolves into an art.”54 And there were also some voices that emphasized selfsacrifice: “yŏnae is moral as it requires self-sacrifice,”55 “innocent yŏnae is selfsacrifice and extends mutual life expectancy,”56 “self-sacrifice is what eventually brings in eternal victory.”57 These views were not, however, based on an understanding that genuine love can only be deepened by marriage, as asserted by Kuriyagawa. The fact of the matter is that Kuriyawaga’s critique of ‘Nora’ in the book Modern Views on yŏnae was not only at odds with the general view of other commentators, who had praised Nora highly, but was also very confusing, with an over-complicated logical structure. Thus, it was that the Chosŏn intellectuals adopted only the non-Nora portion of the book,58 so that by this omission Kuriyagawa’s logic, stressing the completion of personality through the process of persevering and overcoming hardships in marriage, was changed into rather a simplistic structure of ‘yŏnae = sacrifice = completion of personality,’ which resulted in a high level of abstraction. These notions of ‘yŏnae,’ ‘sacrifice’, and ‘completion of personality’ were combined with an image of lofty civilization, accelerating the process of extreme abstraction. This was aestheticized as “yŏnae as a manifestation of a personally integrated and nobly moral mind,”59 or by portraying the condition of a mind in yŏnae as “a state of absoluteness which is not at all different from that of the Buddhist deliverance of souls.”60 Meanwhile, the radical perspectives of yŏnae, such as “yŏnae is the greatest virtue of all in life”61 prevailed, and yŏnae as a manifestation of the divine-self and a symbol of civilized life was established as an ideology.

The direction in which the concepts evolved: toward a high level of abstraction, and toward the formation of an ideology, also affected the semantic field of their derivatives such as ‘chayu-yŏnae’ (自由戀愛 ; free love) and ‘sinsŏnghanyŏnae’ (sacred love). The word ‘chayu-yŏnae’ which is still in current usage, meant ‘free sex,’ and was clearly distinguished from the ‘freedom of love (yŏnae-ŭi chayu),’ in the works of Key and Kuriyagawa. In Korea, on the other hand, where people favor the use of four-character Chinese idioms, the word ‘chayu-yŏnae’ was used more widely to refer to the following four distinct meanings in the early 1920s.

① Men and women choosing partners of their own free will, breaking free of parental control

② Noble love that symbolizes a new quality of civilization

③ Love that allows both parties to marry freely and divorce freely.

④ Free sex62

In the early 1920s, scholars like No Cha-yŏng and Yŏm Sang-sŏp who had encountered overseas theories, distinguished ‘yŏnae-ŭi chayu’ (freedom of love) in the sense of ① from ‘chayu-yŏnae’ (free love) meaning ④.63 However, throughout the entire period of the 1920s, ‘chayu-yŏnae’ as based on concept ① evolved towards bringing ② & ③ under its complete control.64 This meant that ‘chayuyŏnae’ symbolizing ‘freedom of love’ could not be exceptionally conceptualized to mean ‘free sex,’ which has a very negative connotation, whilst the process of conceptualizing the word ‘yŏnae’ as a noble value was continuing to develop at the other end of the spectrum. Although the meaning ‘free sex’ became more widely received for a short time when socialist views on proletarian yŏnae arose later, the word ‘chayu-yŏnae’ was generally perceived as ① throughout the entire colonial period. Moreover, the innovative nature of the word ‘yŏnae’ remained focused on breaking free from the traditional marriage system.

The term ‘sinsŏnghan yŏnae’ (sacred love) has an even more complicated history than ‘chayu-yŏnae.’ From the start, as soon as yŏnae attained common usage, the word ‘sacred’ always went together well with yŏnae, though its meaning was, in fact, very vague. Yŏnae could be sacred because it was a precondition to marriage,65 could be sacred because it was an opportunity to discover one’s spiritual self,66 or could be sacred because it was a concept imported from civilized nations.67 Some asserted that the concept yŏnae itself was sacred,68 while others said that only yŏnae which denies its physical aspect and suppresses human instincts could truly be called sacred yŏnae.69

‘sinsŏnghan yŏnae’ (sacred love) thus became a benchmark wherein all these varying contexts and perspectives were merged, and a single abstract concept wherein all the contradictory meanings of these theses coexisted. Thus, we can see that yŏnae was not a word indicative of what actually existed, but rather it was just an ‘image’, and was only accessed by a fantasy of civilized life. One might say that yŏnae was not finally deliverable as such, but rather was an assembly point where all these controversial perspectives were accessed through imagining aspirational images of civilized life.70

One thing that is very clear, though, is that the meanings of yŏnae were divided by the principle of dominance: superior Western civilization vs. inferior traditional society. And yŏnae was defined by images of Western civilization before even being considered in the context of real life.71 The concept yŏnae, taken together with all these flowery words like ego, sacred, or completion of personality, was no more than an indefinable blind spot where all these images and imaginations of civilized life converged. While the rapid ideological abstraction of the concept continued, it was almost impossible to build a deep understanding, requiring the fine-tuning of the conflict between the ego and the environment, which was necessary to enable the concretization and practicalization of the abstract concept.

28“Sindodŏk ŭl nonhaya sinsahoe rŭl mang (望)-hanora [Discussing new morality and expecting new society],” Tong’a ilbo [Dong-A daily], July 19, 1920. 29Ch’oe Sŭng-man (1919), p. 53. 30“Nyŏ haksaeng munje” [Problem of girl student (6)], Tong’a ilbo [Dong-A daily], September 15, 1920; Hwang Tŭk-sam (1923); “Kaehak ttae rŭl tanghaya kachŏng e han mal i put’ak” [One request for a family around the school starting season, Tong’a ilbo [Dong-A daily], August 27, 1925. 31Chŏn Yŏng-taek (1919), p. 12. 32Kim Ki-jin (1926), p. 20. 33“Chŏngnyŏn’gi ŭi Il-i-pyedan” [One or two evils of the youth], Tong’a ilbo [Dong-A daily], Apr.26, 1921. 34About the acceptance of Ellen Key, see the following: Ku In-mo (2004); Sŏ Chi-yŏng (2008); Chang Kŏng, translated by Im Su-bin (2007); Ch’oe Hye-sil (2000). 35Ellen Key (1911), “Development of Sexual Morality,” p. 5. 36Ellen Key (1911), “The Evolution of Love,” pp. 57–106. 37Kuriyakawa Hakuson, Translated by Yi Sŭngsin (2010), p. 16, 20, 26, 28. 38Ibid., p. 23. 39Ibid., p. 84. 40Kuriyakawa Hakuson, p. 11. 41Ibid., p. 37. 42Ibid., p. 49. 43Ibid., pp. 42–43. 44Ibid., p. 23. 45Ibid., p. 47. 46Ch’oe Sŏ-hae (1926), p. 103. 47Kim Yŏng-bo (1926), p. 57. 48Yang Chu-dong (1926), p. 93. 49Kim Kwang-bae (1926), p. 72. 50Kim Yŏng-jin (1926), p. 35. 51Yi Ik-sang (1926), pp. 54–55. 52Kim Ŏk (1926), p. 99. 53Kim Kwang-bae (1926), p. 73. 54Yu To-sun (1926), p. 88. 55Kim Ŏk (1926), p. 101. 56Na Tong-hyang (1926), p. 95. 57Na Tong-hyang (1926), p. 95. 58According to Chang Kyŏng (2007), similar interpretation arose in China in the similar period. 59Kim Ki-jin (1926), p. 20. 60Kim Kwang-bae (1926), pp. 73–74. 61Ibid. p. 75. 62The followings are examples for each case. : ① ‘There are two types of marriage: chayu-yŏnae marriage and arranged marriage,’ “Myŏngsasungnyŏ kyŏrhonchoya ŭi ch’ŏt put’ak: ch’ŏtnalbam e muŏs-ŭl malhaenna” [What they asked on the first night: Celebritites and ladies’ first request on the first night of marriage], Pyŏlgŏn’gon, Dec. 1928, p. 63.; ② ‘Easily speaking, only sexual intercourse is the truth. Yŏnae and chayu Yŏnae are nothing more than merely abstract and fictional things,’ Song-A(1920); ③ ‘In Russia, because chayu-yŏnae was officially approved, a terminal worker divorced fifteen times in a week,’ “Kyŏngsŏng myŏngmul namnyŏ sinch’un chisang taehoe” [Spring meeting on a paper of notable men and women in Kyŏngsŏng],” Pyŏlgŏn’gon, Feb. 1927, p. 112.; ④ ‘Degradation of the past ethics and vogue of chayu-yŏnae offered them a theory advocating extra marital relationships,’ “Namnyŏhaksaeng ŭi p’unggi munje” [Moral matters of male and female students], Tong’a ilbo [Dong-A daily], Mar. 24, 1924. 63The followings would be the examples: No Cha-yŏng (1922); Yŏm Sangsŏp (1926). 64The fourth meaning was activated when proletarian love was asserted by the socialist group. However, the dominant meaning of the word ‘chayu yŏnae’ was close to the meaning ①, and the innovative aspect of the word also still remained mainly in its meaning of liberation from conventional marriage. 65‘yŏnae is sacred as long as cohabitation is sacred,’ Kim Yun-gyŏng (1926), p. 37. 66‘The joy of discovering oneself in other’s configuration! That leads to the sacred yŏnae when it is highlighted,’ Yeom Sangseop (1926), p. 12. 67‘Their rule of marriage is a sacred free marriage, and their institution of marriage is directly opposed to ours,’ Pak Yun-wŏn (1921), p. 98. 68‘C was the person who believed that the object of love should be one and love was a sacred thing,’ Pak Chong-hwa (1924), p. 183. 69‘They dreamed of sacred spiritual love oppressing the instinct rippling in their chests.’ Sŏnghae (1921), p. 119. 70About the meaning of ‘sinsŏnghan yŏnae’(sacred love), refer to Kim Chiyoung (2006), pp. 246– 251. 71Refer to Kim Chiyoung (2007), pp. 35–73.

Nowadays, the subject of ‘sexuality’ always comes up in any discussion of love between men and women. However, when the word yŏnae was first being formed as a concept in Korean intellectual discourses, the concept of ‘sexuality’ was overshadowed by the spiritual aspects of yŏnae, and it never came to the surface. There were a few cases where the issue of chastity was mentioned, but only to be denied in the context of supporting the marriage of widows,72 and sexuality itself was never brought into the center of attention; any open discussion of ‘sexuality’ was still so new and unfamiliar. And just conducting discourse on issues like the need to resist the conventional marriage tradition was considered quite aggressive enough, back in those times. Even in the theories of Ellen Key and Kuriyagawa Hakuson, concerning the unity of body and soul, ‘sexuality’ remained a secondary element. Although their influence helped yŏnae develop as a concept indicating the ‘civilized’ and moral sublimation of ‘sexuality,’ they continued to focus on ‘civilization,’ ‘personality,’ and ‘sublimation’ whereas ‘sexuality’ remained nothing more than a simple biological starting point.

But, as more was done in practice to modernize the approach to yŏnae, and more voices lent their support to the theory of the unity of body and soul, the debate on sexuality gradually picked up some momentum. ‘Sexuality’ then emerged as a subject of formal discourse, with yŏnae between men and women characterized as “sexual attachment,”73 “something that came from an intense passion to fulfill one’s own sexual desires,”74 or “something that originated from sexual instincts.”75 What fiercely fueled the debate was the proletarian sexual morality theory of Alexandra Kollontai (1872–1952)76 .

Kollontai, a feminist and revolutionary in the Russian revolution, was inspired by her awareness of issues like gender inequality, unhappy marriages, and sex trafficking, to develop a radical theory of sexual liberation. Kollontai, who believed that gender inequality was caused by the economic dependency of women, asserted that a woman who lacks economic independence readily allows herself to become a ‘dependent being’ even in a love relationship, and is highly likely to end up in a marriage where she is dominated and restrained by a possessive partner. Kollontai proposed that the long-established social system, which locked women’s productivity into a traditional family structure, could and should be improved, and maintained that the traditional family system should be dismantled. Kollontai’s ‘red love’ puts forward a vision of an unfettered love, formed through companionship, which encourages both partners to engage socially and politically, rather than seeking to dominate one another.

Kollontai’s theory was first introduced to Korea in 1920,77 but it was not until the late 1920s and the early 1930s that it received widespread attention. During this period, it was Chosŏn socialists who showed the most interest, as they were critical of Key and Kuriyagawa, arguing that their esteem for yŏnae represented just a petty-bourgeois love based on individualism and that “their theories are unwittingly purposed to suppress all complaints and discontent with life, under the name of domestic peace.” Socialists of the period believed that yŏnae should not transcend class interests, but rather, being based on real life as it is lived, yŏnae should coincide with class interests. They advocated Kollontai’s theory from the standpoint that accompanying yŏnae is necessary for social progress.78

However, there were different views on Kollontai even among socialists. At issue was the “instinctive (mechanical) satisfaction of sex,” introduced by Kollontai as a way of breaking free from possessive desires, restriction, and control. While, on one hand, suggesting that women should adopt an idealistic attitude to love in a socialist society, Kollontai, on the other hand, depicted a Soviet woman named Jennia who chose a loveless life that only satisfied her biological desires in a novel entitled The Loves of Three Generations.79 Jennia’s choice was a result of her belief that women in a socialist society were always too busy with their social commitments, and did not have enough time for love. Jennia’s views on love represented an unconventional radical perspective on sexuality, and were repeatedly discussed among intellectuals of colonial Korea, mainly with regard to the issue of “instinctive satisfaction of sex.”80 Jennia’s views on sexuality were later stereotyped as a voice representing Kollontai’s theory, which became an established concept called ‘Kollontaism,’ This means that the original intent of Kollontai’s theory, which claimed to address gender inequality and to renovate the conventional structure of dependent love, was thrown out the window. Ultimately, Kollontaism acquired a bad reputation, regarded as tantamount to promoting promiscuity.81

From the perspective of conceptual history, then, it is important to understand that the conventional concept yŏnae, which had been made highly abstract, started transforming the more it became tied in with sexuality.82 Increasingly, sexuality was considered as the overriding issue of interest. Even the socialist camp asserted, “yŏnae is a perfunctory expression of sexual life,”83 and “yŏnae is not a matter of the mind. A loving mind naturally comes with sexual desires;’84 while the non-socialists declared that the objective purpose of yŏnae is procreation.85 Even some followed Jennia’s views and advocated treating the body and soul separately, asserting that “sexual desire and yŏnae should be considered separated!”;86 while an essay in the late 1930s by a female poet, who admired spiritual yŏnae without physical intimacy, was heavily criticized as simple “fantasy and illusion.”87 As more people approached the concept yŏnae from the perspective of biological desires, the original nobility of yŏnae significantly eroded.

This new forthright approach to sexuality, and the loss of nobility of yŏnae were not entirely unconnected with the emergence of a strong current of criticism about the culture of dating. With the widening gap between ideal love and real-life love, the autonomous dating culture of young men and women in colonial Korea generated contention on many issues, including conflicts with their parents’ generation, problems with the early marriage culture, a huge wave of suicides, divorce lawsuits,88 a new generation of women becoming concubines, and the culture of kisaeng (female entertainers).89 After the mid 1920s, even young intellectuals who admired yŏnae became vocally seriously critical about the yŏnae culture of the times. Anecdotes about disappointment and disillusionment with love marriages were most frequently mentioned,90 and a more cautious attitude towards “yŏnae easily earned and easily lost”91 now prevailed in society.

After the mid-colonial era, those writers who had once stressed the significance and value of yŏnae, began to be profusely critical, remarking that “yŏnae is all the rage now, but it is nothing more than ‘playful,’ ‘dirty,’ and ‘inexperienced yŏnae,’”92 and that “young men and women these days mis- understand yŏnae, get themselves into sexual indulgence, and give rise to public criticism in society.”93 The ‘pursuit of sensual pleasure’ and the ‘pursuit of speed’ were seen as characteristic features of yŏnae in those days.94 Indeed, since “yŏnae... was criticized as nothing but enjoyment, consumption, and pleasure,”95 there was intense condemnation of sexual immorality and materialistic lifestyles.96

We must remark, here that the fierce criticism of sexual and materialistic desires, as driven by yŏnae, showed a conspicuous gender bias by predominantly targeting women. While such criticism arose like “in the recent trend of yŏnae, (…) economic conditions are cited as the top priority,”97 those who are portrayed as representative of materialistic desires, or who “put money first,”98 before personality, as a condition for marriage, were mainly drawn from the educated new generation of women. Such women were condemned as the enemies of yŏnae “whose heart is throbbing at a fat wallet and money in bank accounts, a posh Western-style house, and luxury items like pianos, rather than at personality or looks,”99 and are slaves to materialism who “live on so-called compensation for chastity.”100

The new generation of women was emblematic of sexuality. “Indulging in sexuality too much as liberated women,”101 was often cited as a particular characteristic of those days. Even some female writers agreed to the condemnation expressed by one magazine’s editor-in-chief: “The way the new generation of women loves (...) shows a pattern of women rushing towards the opposite sex, just because of ‘sex’ or in other words, because of their overwhelming sexual impulses.”102 Newspapers and magazines often published articles on the splendors of yŏnae, and the marriages of socially significant members of the new generation of women. Articles such as “Report of Women with Short Hair-cuts” [Tanbalyŏbo] (Pyŏlgŏn’gon, October,1927) openly disclosed the marriages, divorces, cohabitations, out-of-wedlock births and pregnancies of prominent female figures: “Chosŏn’s Top 10 Female Big-Timers [Chosŏn yŏryu 10 kŏmul yŏlchŏn]”(Samch’ŏlli, Nov.1931), “A Controversial Female Nude: The Path She Walked Down” [Munje yŏsŏng-ŭi nach’esang: Kŭ tŭl ŭn ŏttŏhan kil ŭl palba wanna] (Cheilsŏn, November, 1932), “The Marriage Symphony of an Intelligent Woman” [Int’elli yŏsŏng ŭi kyŏrhon kyohyangak] (Chogwang, Dec.1935). The glamorous love affairs of Na Hae-sŏk, Kim Wŏn-ju, Kim Myŏng-sun as well as the scandals of those who practiced ‘red yŏnae’ such as Hŏ Chŏng-suk and Chu Se-juk, both satisfied the public’s taste for vulgarity and provided ammunition for those campaigning against indiscreet yŏnae and seeking to uphold the notion of chastity.

The media that collectively criticized and underestimated women’s subjective choices demonstrated that the voluntary exercise of yŏnae independent from parental control and also the right to divorce were actually intended only for men, not for women,103 which hardly differs from the long-established custom of strictly restricting women’s sexuality under the rubric of ‘chastity.’ Yŏnae, as a channel for the youth to express their interiority and to find their own ego, was indeed instrumental in forming the modern subject, but this process could not reach far enough to overturn the deep-seated understanding of women’s sexuality as something that had to be controlled.

On an ideological dimension, yŏnae was a concept based on equal rights both for men and women, but, in reality, women of colonial Korea were not regarded as equals, but just as ‘the others’ who were obliged to become a ‘men’s wives.’ In an environment where a woman could never become a sexual subject, yŏnae, a concept that overturns the asymmetric gender structure, was impossible to realize. The concept of yŏnae was therefore degraded to refer to the stage of ‘dating’ for the purpose of marriage, in which a discriminatory double standard on sexuality is implicit, thus maintaining the asymmetric gender structure.

From the 1930s, the buzz for yŏnae began to lose energy, and yŏnae became gradually more conservative. The linkage between yŏnae to marriage was becoming more established, and some even aestheticized marriage: “marriage is the leaves and branches of yŏnae,”104 and “marriage is a beautiful hill that helps yŏnae become more mature and reach its peak.”105 One article from Pyŏlgŏn’gon even established a ‘yŏnae constitution’ stipulating: “Yŏnae has an obligation of marriage. Yŏnae shall be limited to only once per lifetime. (…) Yŏnae shall continue throughout the whole of life.”106 The same article also suggested chastity as the noblest virtue of yŏnae: “the value of yŏnae is set to be chastity.”107 The notion that “one requirement for marriage, even in free-yŏnae marriage, is chastity”108 found widespread support.

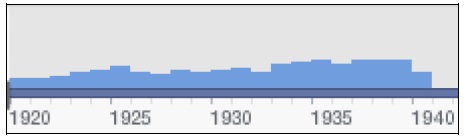

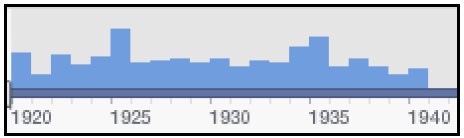

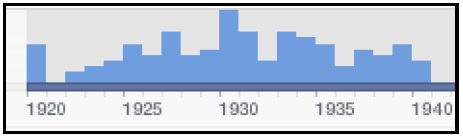

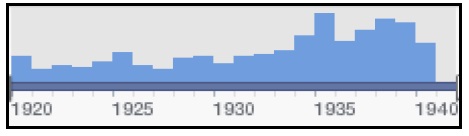

The following charts show the frequency with which news articles, published in Tong’a ilbo during 1920–1940, included the words ‘yŏnae’ (Chart 1), ‘yŏnae’ and ‘free(chayu)’ (Chart 2), ‘yŏnae’ and ‘chastity’ (cheongjo) (Chart 3), and ‘yŏnae’ and ‘marriage’ (kyŏrhon) (Chart 4).109

The charts show that articles mentioning both ‘yŏnae’ and ‘chastity’ appeared more frequently from 1925 onwards, surging in the early 1930s; while articles mentioning both ‘yŏnae’ and ‘marriage’ began to appear more frequently from the late 1920s, with a conspicuous increase from the mid 1930s.110 The increasing frequency of articles including ‘yŏnae’ and ‘chastity’ (chart 3) and ‘yŏnae’ and ‘marriage’ (chart 4) make a good contrast against the fact that articles including ‘Yŏnae’ and ‘free’ (chayu) together show an almost even frequency from 1920 to the late 1930 and decrease at the end of the 1930s (chart 2). The statistics and the frequency of the mere appearance of the words alone hardly provides the full picture, but the contrast between chart 2 and chart 3 & 4, increases the possibility that ‘Yŏnae’ became more conservative during this period.

It should be understood that ‘chastity’ in this context was a word referring specifically to the restriction of women’s sexuality. Even the Civil Code stipulated a ‘wife’s obligation of chastity’ as one of ‘the effects of marriage,’ along with mutual support, mutual respect, yŏnae, and cohabitation. The act of adultery itself was sufficient for a husband to file for divorce against his wife. In order for a wife to start divorce proceedings against her husband, however, he had to have been actually sentenced for adultery, which clearly constituted discrimination against women.111

In the mid-to-late colonial period, yŏnae lost its innovative value and was swept up in the tide of the marriage system. Yŏnae as a concept was diminished to refer to the phase of dating before marriage, and sexual encounters were forbidden at the Yŏnae stage, because the essence of Yŏnae was meant to be a conduit leading toward marriage. On the double standards where restriction of sexuality operated unfavorably only to woman, the concept Yŏnae functioned as a requisite for the family-system-reformation, which was endorsed by Japanese Imperialism, by playing a role in restricting women’s sexuality to the domestic area.

72Yi Kwang-su (1917), pp. 33–34. 73Kim Yun-gyŏng (1926), p. 38. 74Ch’oe Sŏ-hae (1926), p. 107. 75Kim Ki-jin (1926), p. 18. 76Aleksandra M. Kollontai started to be known with her novel Vasilisa Nalygina, which was translated with the title of Pulgŭn sarang [Red yŏnae] and Samdae ŭi sarang [Love of three generations] in Korea. About Kollontai’s theories, see Yi Chŏng-hŭi (2008). 77“Puinhaebangmunje e kwanhayŏ [About the liberation of women],” Tongnip sinmun, April 13, 1920. 78The following are the essays that affirmed the acceptance of the theory of Kollontai: Chŏng Chil-sŏng (1929); Kim Ok-yŏp (1931); Kim On (1930); Cho Kuk-hyŏn (1931); Yi Sŏk-hun (1932). 79Aleksandra M. Kollontai, Translated by Chang Chi-yŏn (1993). 80About the Korean accommodation of Kollontai, see the following: Sŏ Chi-yŏng (2008); Yi Taesuk (2006); Sŏ Chŏng-ja (2004). 81The following are essays that criticized the theory of Kollontai as decadent love: Ryu Ch’ŏl-su (1931); An Hwa-san (1933); Sin Sang-ju (1931); Yun Hyŏng-sik (1932); An Tŏk-kŭn (1933). 82The theory of Kollontai also aroused diverse polemic practices among some women and socialists. This article restrictively focused on the affection of the theory according to dominant social thought, excluding polemic practices. 83Yun Hyŏng-sik (1932), p. 58. 84Kim Ok-yŏp (1931), p. 9. 85Yi Chong-u (1935). 86Chŏng Chil-sŏng (1929), p. 5. 87An Tŏk-kŭn (1938), p. 161. 88According to the writer of the following article, a half of the trials in court were divorce trials in those days. CM (1921), pp. 87–91. 89About the cultural change caused by the new trend of love, see Kwŏn Podŭrae (2003). 90There are many articles that alluded to failures or regrets of a marriage resulting from chayu yŏnae in the public journals of the 1930s. The following are random examples: Puk ungsaeng (1930); “Manhont’agae (晩婚打開) chwadamhoe” [A round table talk for the solution of late marriage], Samch’ŏlli 5, No. 10. 1933.; “Aein ŭl ppaeatkin Ch’ŏngch’un piga(悲歌) [Elegy for the youth deprived of a lover],” Samch’ŏlli 4, No. 5. 1932. 91Yi Sŏn-hŭi (1938), p. 30. 92Pang In-gŭn (1927), p. 147. 93Kim Tong-su (1935), p. 31. 94“Yŏryu munsa ŭi ‘yŏnae munje’ hoeŭi” [Convention for the yŏnae matter of women writers], Samch’ŏlli 10, No. 5. 1938, pp. 314–315. 95“Modern college kaegang” [The beginning of lectures at a modern college], Pyŏlgŏn’gon 28, 1930, p. 53. 96About the criticism on the new women in the 1930s, see the following: Sŏ Chi-yŏng (2008); Ch’oe Hye-sil (2000); Yi Myŏngsŏn (2002); Kim Kyŏng-il (2004); Modern Media Research Group in Suyu+trans (2005). 97Mo Yunsuk (1937), p. 31. 98“Yŏryu munsa ŭi ‘yŏnae munje’ hoeŭi” Op.cit., p. 315. 99Ryu Kwang-nyŏl (1933), p. 44. 100Hoyŏndangin (1933), p. 35. 101“Sisangmanhwa”, Pyŏlgŏn’gon 30, 1930, p. 71. 102“Yŏryu munsa ŭi ‘yŏnae munje’ hoeŭi” Op. cit., p. 313. 103Refer to Yi Myŏng-sŏn (2002), pp. 84–115. 104Yŏm Sangsŏp (1932), p. 91. 105Pang In-gŭn (1932), p. 94. 106“yŏnae-hŏnbŏp” [A yŏnae constitution], Pyŏlgŏn’gon 18, 1929, p. 153. 107Ibid. 108Chŏn Yu-dŏk (1927), pp. 153–154. 109Above charts are based on the search engine of the NAVER News Library (http://newslibrary.naver.com) on the web. 110The increasing frequency of articles including the words ‘yŏnae’ and ‘kyŏrhon’ [marriage] together responds to the increasing frequency of the articles including the words ‘yŏnae’ and ‘honin [matrimony],’ which ranked 114 cases in total during the given period and appeared more frequently from 1932 as seen in chart 5 below. If we add the number of cases from chart 5 to the number of cases from chart 4, we can find that the trend of combining ‘Yŏnae’ and ‘marriage’ increases in the 1930s. 111Kang Kŏ-bu (1928), pp. 142–145.

yŏnae, which was coined to refer to a modern form of love, was a contentious concept that stimulated discourse on a wide variety of social issues. Yŏnae promoted a restructuring of the family system and brought about a shift toward a modern perception of self and interiority. ‘Yŏnae’ facilitated a transformation from a patriarchal family structure, oriented around the father-son axis, to the modern conjugal family system. ‘Yŏnae’ acknowledged the reality of human passion for the opposite gender, and granted it public recognition. This resulted in changes in the perception of such passions, and created much discourse. The rise of Yŏnae was not, however, driven by a sense of unhappiness with the traditional marriage system nor by autochthonic commitment to marriage reform. What made Yŏnae seem more logical than the status quo were the theories of Yŏnae espoused by Ellen Key, Kuriyagawa Hakuson, among others, which were enthusiastically received by young intellectuals, even though their knowledge of such theories was fragmentary in some ways. These imported ideas prompted a high level of abstraction. Thus, by ignoring the eugenic aspects of Ellen Key’s theory, and omitting a sense of self-sacrifice in marriage from Kuriyagawa’s theory, a rough equation, something like “sublimation of sexual desires = Yŏnae = civilized personality = self-completion = self-sacrifice,” was establishhed. Subsequently, Yŏnae became abstractified into a concept that enables the expression of a noble ego and the completion of one’s personality, a benchmark to which the progressive modern youth aspired.

By the time that some real-life experience had been built up, however, and Kollontai’s theory of proletarian love had meanwhile given rise to free-spirited love, elements cognizant of ‘sexuality’ started flowing into the semantic field of yŏnae. Conventional perceptions of sexuality, together with deep-seated stereotypical views about women’s sexuality, allowed the whole concept of yŏnae to become conservative. Poignant criticism began to be directed at the pattern of free-spirited love, and the concept of Yŏnae was degraded and reduced to refer to the stage of dating for the purpose of marriage. The concept Yŏnae imposed a sexual double standard that was hostile to women’s sexuality. This meaning contributed to the pursuit, by Imperial Japan, of a modern family structure by restructuring the traditional family system.

Infatuated by the images of abstract love propagated by Western civilization, the concept of yŏnae functioned as a disengaged ideology rather than as creative energy to portray individuality in the realities of everyday life. Because its abstract images were disconnected from daily life, yŏnae became subjugated under the secular familism of the colonial middle class and the gender hierarchy.