INTER-CORE RELATIONSHIPS AND NETWORK DIFFUSION

Previous studies of regional integration4 can be divided into roughly four different schools of thought: neofunctionalism, constructivism, realism, and liberal intergovernmentalism. Neofunctionalism emerged as an explanation of the evolution of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) and the founding of the European Economic Community (EEC). Haas argued that, once started, early decisions of economic integration created unintended or unwanted consequences that constrain subsequent choices (Haas 1958). Haas further distinguished this mechanism, called “spillover,” into three types: functional spillovers (interdependent sectors eventually integrate under the pressure of experts and political elites), political spillovers (cooperation among supranational officials in one sector emp ower them to work as informal political entrepreneurs in other areas), and cultivated spillovers (centralized institutions representing common interests work as midwives to integration). In the view of neofunctionalists, the driving force of economic integration is based on endogenous factors (i.e. spillovers) and the integration process was a smooth evolution from low-level integration to deeper and wider levels. State actors do not have privileged positions in neofunctionalism: supranational elites and organizations were seen as important as state actors. Recently, historical institutionalism revisited the neofunctionalist argument, emphasizing the unintended consequences of early decisions of institutionalization on the integration process (Pierson 1996).

Constructivist explanations of integration emphasize the intersubjective nature of the integration process. Constructivists stress the role of ideational factors, such as rules, norms, languages, and identities, to building common understandings on the complex issues shaping the paths of institutional development. For example, Checkel argues that convergence of identities and preferences through social learning and social mobilization, or ‘Europeanization,’ played a major role in European integration (2001). Similarly, Jachtenfuchs, Diez and Jung argue that the integration process “depends not only on interests but also on normative ideas about a legitimate political order (‘polity-ideas’). These polity-ideas are extremely stable over time and resistant to change because they are linked to the identity and basic normative orientations of the actors involved” (1998, 407). Constructivist arguments fill an important void in the literature by highlighting the integration process as an outcome of intensive “intersubjective” interactions. However, constructive frameworks show weaknesses in successfully weaving their ideational explanations with structural factors such as power politics, economic preferences, and geopolitical concerns and, as a result, constructive explanations often “risk being empirically too thin and analytically too malleable” (Hemmer and Katzenstein 2002, 583).

Realists believe that regional integration is an outcome of power politics. For Rosato, for instance, economic integration in Europe was an attempt by France and West Germany “to balance against the Soviet Union and one another” (Rosato 2011, 2). Balancing and forming alliances are usual practices of power politics and hence the path to European integration can be shifted, stopped, and accelerated any time when major European players change their strategies. Similarly, Grieco notes that the cause of the integration hinges on the power gap between the major regional players and weaker states (1997). The huge power disparity between major Asian states and weaker states made it difficult to achieve European-style integration. Likewise, realists think that integration is nothing but a result of the interplay of power politics among major powers, and so place very little importance on the role of nonmaterial or endogenous factors. As Moravcsik puts it succinctly, realists explain the integration process “by omission” (Moravcsik 2013, 781).

Criticizing both neofunctionalism and realism, Moravcsik presented a theory of liberal intergovernmentalism as an alternative (Moravcsik 1998, 2005, 2013). Moravcsik claimed that neofunctionalism relied too much on endogenous factors such as spillover and, as a result, neofunctionalism fails to stand alone as a scientific theory that produces complete, falsifiable, and consistent hypotheses. In contrast, realism reduces the complex process of European integration to a single cause (power politics) and, as a result, fails to provide proper explanations for the important moments in the integration process that cannot be reduced to power politics.

Moravcsik takes a multi-causal approach that embraces the role of domestic preferences, power politics, and supranational institutions. First, like realists, he emphasizes the role of state actors in the process but stresses “state preferences” as a key concept that includes economic interests and geopolitical concerns. Then, differences in bargaining power among major powers determined the outcomes of substantive agreements. Once substantive agreements on integration are made, states created institutions to secure these outcomes under future uncertainty. In Moravcsik’s theory, intergovernmental bargaining played the role of connecting micro-level factors (state preferences) and macro-level factors (institutional choice). In this view, the process of European integration consists of multiple stop-and-goes, punctuated by important deals among major European powers.

We agree that both endogenous factors, such as spillover or diffusion, and exogenous factors, such as power politics, matter to the integration process. We also believe that the integration process has both continuities and changes, which represent important turning points (critical junctures) in the integration process, and these turning points were made possible by intergovernmental bargaining among major European powers. However, an important question is how to explain the dynamics of integration over a long period of time, with proper emphasis on important changes and the stable lock-in effects of endogenous factors. In the following, we propose our view that explains regional integration as a diffusion process with punctuated equilibria and present a theory of ICR as a meso-level explanation focusing on Asia and Europe.

1Recently, scholars of international relations increasingly view the complex interactions in international relations through the framework of “networks.” See Hoff and Ward (2004), Hafner-Burton et al. (2009), Merand et al. (2011), Carpenter (2011), Cranmer et al. (2011), and Maoz (2011). 2Accessible at http://worldtreatyindex.com/. For more information on the database, see Pearson (2001). 3Unfortunately, regular updates stopped in 2003. As our argument covers mainly the history of the 20th century, the lack of 21st century data does not hamper our analysis much here. However, it would be highly interesting to extend our analysis using post-2003 data given the growing importance of Chinese influence in Asia and the world in the early 21st century. 4Regional integration is commonly defined as “the concentration of economic flows or the coordination of foreign economic policies among a group of countries in geographic proximity to each other” (Mansfield and Milner 1998, 4). Haas (1958) provides a more nuanced definition of integration: the process “whereby political actors in several, distinct national settings are persuaded to shift their loyalties, expectations and political activities toward a new centre, whose institutions process or demand jurisdiction over the pre-existing national states” (Haas 1958, 16).

A PUNCTUATED MODEL OF REGIONAL INTEGRATION

We consider regional integration as a punctuated diffusion process. Regional integration is “punctuated” with many stop-and-goes, critical moments, and stalemates. Regional integration is a “diffusion” process because regional integration involves the coordination of policies, the convergence of ideas, and the spread of institutions across nations.

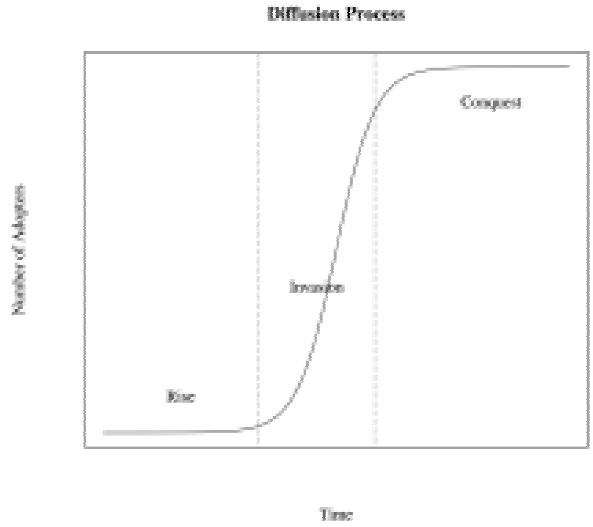

The diffusion process in a society is most commonly explained as a S-shaped curve as shown in Figure 1. However, the S-shaped curve-based explanation of diffusion has not been fully embraced by social scientists, who generally have not accepted that diffusion in human networks is an irreversible, deterministic process without competition.

Even a successful case of diffusion resembles “stop-and-go” patterns rather than the smooth shape of the S-shaped curve. Therefore, it is appropriate to conceptualize the process of diffusion as a combination of several distinct regimes (or stasis), not as realizations of a homogeneous dynamic process, which is why we are conceptualize the process of diffusion as a punctuated.

Recent studies of diffusion in biology and sociology emphasize the punctuated nature of the diffusion processes (e.g. Loch and Huberman 1999; Boushey 2012). For example, Bejan and Lorente characterize the diffusion process as a combination of three distinct stages (or regimes): rise, invasion, and conquest (Bejan and Lorente 2011). In the initial stage, a new idea arises and a small group of countries adopt it. These countries can be called “innovators.” During the invasion stage, a critical mass of countries adopts the new idea initially embraced by innovators. Finally, the invasion is accelerated and the stage of conquest starts. Countries that have not yet adopted the idea experience negative externalities and incur increasing costs related to staying out of the diffusion process.5

Our punctuated-equilibrium model emphasizes the invasion stage as a critical moment of diffusion. This is where a critical mass of actors makes strategic decisions to join or not to join a proposed innovation. Regional integration starts from a small group of countries with similar economic preferences (Moravcsik 1998), similar security threats (Rosato 2011), or equal powers facing collective problems of economic interdependence (Grieco 1997). The idea of integration is proposed as a long-term solution to the collective problems they encounter and is adopted by some “innovators.” In the case of European integration, they were six founding members of EEC (West Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg). Theories of integration that emphasize the role of exogenous factors such as realism, rational institutionalism, and liberal intergovernmentalism well explain the ‘rise’ stage of European integration. Furthermore, there must not be much disagreement once a majority of countries adopts a certain innovation during the post-invasion period, so the constraining effect of early decisions (spillovers or institutional lock-ins) must be strong enough to change the preferences of insiders and outsiders in the network. Thus, the most important and critical question in the study of diffusion is what caused the process to reach critical mass such that the diffusion process becomes almost self-sustaining? This will be discussed below.

What causes the moment of critical mass in the process of regional integration? It is difficult to provide a comprehensive answer to this question in this paper partly because we do not have a well-defined concept of “region” in international relations.6 Instead of attempting to provide a generalizable theory for all potential “regions” in the world, we provide a meso-level theory focusing on Asia and Europe where the social construction of region has been developed relative to other parts of the world.

The reason we delimit our focus to Asia and Europe is not just a practical one but also a theoretical one. There is a similarity in regional network structures in Asia and Europe in the early postwar period, which allows a theoretical leverage to our analysis. Both Asia and Europe had “multiple cores” and were exposed to the influence of superpowers (the US and the USSR during the Cold War) although the degree and nature of the exposure differed between Asia and Europe.7 For this reason, windows of opportunity for a change in the regional order came when the strategic interests of the superpowers changed. For example, the relationship between France and West Germany changed dramatically around the Berlin Crisis of 1961, as French President Charles de Gaulle supported German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer consistently, while the US showed a lukewarm attitude toward the Soviet Union’s threat to West Germany. China and Japan also had an important opportunity for a change in their bilateral relationship in the 1970s after Nixon’s visit to China.

Given this structural similarity, we note differences in the bilateral relationship between cores of each network in Asia and Europe, which we call the inter-core relationship (ICR), as the key explanatory variable to differences in the evolution of regional network between Asia and Europe. In this paper, we define “cores” as pivotal players in regional network with de facto veto power over proposals for regional integration. Using this definition, we consider China and Japan in Asia and France and Germany in Europe as the “cores” of each regional network.8 In network literature, cores are defined as densely connected central actors. However, this static definition is not useful to explain the dynamic process of integration. Dense connections and central actors are visible only when integration reaches a certain level. Our alternative definition of “cores,” pivotal regional players with de facto veto power, is applicable to early stages of integration or even pre-integration periods.

More specifically, we argue that the Sino-Japanese relationship in Asia and the Franco-German relationship in Europe have maintained a similar structural position in each regional network but played very different roles in shaping the paths of integration in Asia and Europe. France and Germany, once conceived as “improbable partners,” have jointly played “pivotal roles in shaping Europe” during the postwar period (Calleo 1998, 1; Krotz and Schild 2014, 4). The joint leadership by these two pivotal players in Europe has been essential in overcoming obstacles to the economic integration of Europe. In contrast, China and Japan have acted like “two tigers” that compete to “occupy the same mountain” since the end of the World War II and have failed to generate any serious momentum for regional integration (Yahuda 2001, 1).

China and Japan had an opportunity to transform their bilateral relationship in the 1970s. China had good reasons for its rapprochement with Japan. From political standpoints, the PRC wanted formal Japanese recognition to bolster its legitimacy as the sole government of China, to include Taiwan,9 while trying to break free from the USSR’s encirclement.10 Another motive was economic. Given the miraculous economic rise of postwar Japan, China’s internal goal of development provided strong incentives for China to normalize its relationship with Japan. From Japan’s perspective, however, motivations for rapprochement were more political than economic. Domestically, supra-partisan pressure, e.g. the Japanese Diet’s Men’s League for Japan-China Friendship and Federation Political, and various interest groups, such as the Federation of Economic Organizations, had strengthened support for pro-Peking foreign policies.11 External shocks such as Nixon’s visit to Beijing in 1972 also provided the drive for Japan to reexamine foreign policy alignments and its relationship with China. However, the Sino-Japanese Peace and Friendship Treaty in 1978 “did not directly involve any major legal obligations or commitments on either side” (Lee 1979, 420) and failed to produce enduring legacies, such as regularized summit meetings and ministerial councils, as in Europe’s Élysée Treaty.

Then, what are the specific functions of a cooperative and robust ICR in the integration process? As exemplified by France and Germany in the process of European integration, a cooperative and robust ICR can provide several public goods that can contribute to reaching a critical mass for regional integration.

First, a cooperative and robust ICR can provide the function of co-leadership. Cores have de facto veto power and hence can block any change they do not want to see happen. However, in the presence of multiple cores, individual cores cannot change the status quo without the consent of other cores. The presence of multiple cores under shared leadership can serve as a check against unilateral actions or defection by a powerful state. In this way, shared leadership can legitimize the proposal for change in the absence of formal organizations. This legitimizing effect is particularly important in the early stage of integration in which institutionalization has not fully matured. In the early stage of integration, smaller states may fear that their minor positions could render them helpless in the face of unilateral actions by powerful states in the latter stages of integration. Thus, shared leadership makes it easy to induce the compliance of peripheral countries in the early stages of integration.

Second, a cooperative and robust ICR can perform the function of quasi-representation. Multiple cores can represent the heterogeneous interests of peripheral countries better than a single core. In the case of European integration, Krotz and Schild (2014) explain that the different views of France and Germany on the directions of European integration actually helped the integration process because these heterogeneous views between the cores of Europe served to better represent the views of peripheral countries.

Third, the combined bargaining powers of a cooperative and robust ICR can be highly instrumental in rewarding norm compliers and punishing norm violators during the integration process. As Moravcsik argued, the bargaining powers of key European actors have been important in sealing a deal on such sensitive issues as the Common Agriculture Program (Moravscik 1998). Issue linkages and offers of side payments were more effective and credible when the key European powers of France and West Germany teamed up as a bloc instead of competing against each other.

Lastly, a cooperative and robust ICR produces a stronger commitment to multilateral institutions. In the early stage of integration, weak states hesitate to join due to uncertainty over distributional gains, power asymmetry, and loss of autonomy. Regional multilateral institutions such as the ECSC, the European Commission, and the European Court of Justice are established to lessen these concerns from uncertainty about the integration process and to address complex problems of integration efficiently. Despite the establishment of regional multilateral institutions, member states and the European Council still remained the most powerful actors involved in integration, and powerful states can attempt to change regional multilateral institutions for their gains. The presence of a cooperative and robust ICR decreases the probability of opportunistic behaviors by strong states because of the existence of another strong power that can punish defections.

Our theory of ICR is well connected to liberal intergovernmentalism in that both emphasize the critical role of major European states in creating multiple momenta for integration. However, what makes the role of intergovernmental bargaining so special in the integration process, according to our theory, is not their individual traits (e.g. bargaining power, geopolitical importance, and economic size) but the relationships between them. The relational properties of core European actors, especially France and West Germany, matter much more in creating important momenta for integration.

On the other hand, our theory shares commonalities with neofunctionalism and historical institutionalism in that both emphasize the limited degree of state actors’ control over the integration process. Integration is a diffusion process in which actors have limited control over how their early decisions shape subsequent choices. Learning, emulation, peer pressure, path dependence, and institutional binding are examples of important endogenous dynamics in a diffusion process. However, we depart from neofunctionalism and historical institutionalism in that these endogenous dynamics do not automatically turn on during the diffusion process. A critical mass of adopters is required for a diffusion process to generate a self-sustaining force, and we argue that the ICR between France and West Germany in the 1960s is exemplar in this regard. The ICR between China and Japan did not generate a similar critical mass for further integration in Asia.

Scholars of European integration have noted the critical role of the Franco-German relationship in various ways. For example, our concept of ICR is closely related to the “embedded bilateralism” proposed by Krotz and Schild (2014). Krotz and Schild argue that “neglecting the special bilateral Franco-German connection and two countries’ joint role in the European Union mean missing crucial aspects of European politics” (2014, 1). Then, they theorize the Franco-German connection by “embedded bilateralism” that “captures the intertwined nature of a robustly institutionalized and normatively grounded interstate relationship” (Krotz and Schild 2014, 8). For them, the Franco-German relationship is “just one important instance of a (potentially) larger class of empirical phenomena in institutionalized multilateral settings or regional integration contexts” (Krotz and Schild 2014, 9). In this paper, we further their argument by embedding it in a general theory of diffusion.

Webber explains that regional integration in Asia during the Cold War was infeasible because there was no ‘France.’ That is, Japan’s relative economic power was too strong compared to other non-Communist countries and China could not provide a counterweight (Webber 2006). Our reinterpretation of Webber’s “no France in Asia” argument is that what was missing in Asia was a bilateral relationship like the one between “France and Germany.” Asia would be a lot like Europe if there existed an Asian power that could have filled the role of France for Japan.

Mattli provided another rationale for the joint role of cores in the integration process (Mattli 1999). Mattli explains that regional integration can be successful if states want access to wider markets, and the political leaders of those states are willing to accommodate the political costs of the integration. Political cost here means concession of political autonomy in exchange for economic benefits from integration. If the fear of losing autonomy or distributional concerns is too strong, the cost rises sharply and the supply drops. Thus, the success of integration depends on how to reduce future uncertainty. Mattli argued that this problem is easily solved by the presence of a regional leader “such as Germany in the European Union, Prussia in the Zollverein, or the United States in the North American Free Trade Area” because such “a state serves as focal point in the coordination of rules, regulations, and policies; it also helps to ease distributional tensions through, for example, side-payments” (Mattli 1999, 56). While we agree with Mattli’s point that regional leaders play an important role in providing focal points for coordination problems, we disagree with his reading of the history of European integration. It is highly debatable whether West Germany has been the sole leader of European integration since the 1940s.12

To sum, a larger amount of public goods for integration can be provided by a cooperative and robust ICR more than by the sum of each core’s contribution in the absence of a cooperative and robust ICR. However, two important caveats need to be mentioned. First, we do not claim that a cooperative and robust ICR is a major driving force of the entire integration process. As mentioned above, the integration process can be best understood as a punctuated process with moments of dramatic changes and periods of smooth evolution. The critical role of a cooperative and robust ICR in this punctuated diffusion process is rather limited to the moment of critical mass, after which the rate of integration becomes accelerated by including a significant number of countries in the integration process. Before that moment of critical mass, exogenous factors matter more than the ICR. Also, after critical mass is reached, endogenous factors, such as institutional lock-in, spillover, and network externalities, matter more than ICR. However, we argue that the moment of critical mass in regional networks with multiple cores and outside superpowers hinges critically on the presence of coleadership by pivotal regional players in each network.

The second caveat to our meso-theory of ICR is that the presence of a cooperative and robust ICR increases the possibility of achieving critical mass, but it does not guarantee it will happen. A cooperative and robust ICR may exploit its superior position at the expense of peripheral states and impose a regime that distributes more gains toward ICR members.

5The punctuated nature of diffusion can be found in many examples from the history of international relations. The diffusion of the gold standard in the late 19th century is a good example. England adopted the gold standard in 1844. The decision was related to dramatic changes in the domestic circulation of gold versus silver coins and subsequent enabling legislation, England’s Bank Charter Act. In 1871, Germany adopted the gold standard. The recently-unified German nation wished to have the monetary standard of England and reparations from the Franco-Prussian War provided the resources. In other words, England and Germany were “innovators” or “early adopters.” Once Germany decided to follow the British way of underwriting its monetary system, neighbor countries followed the same path: Norway in 1874, and Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, and France in 1875. The adoption of the gold standard by these countries significantly dropped the market price of silver in international markets. Countries maintaining the silver standard or the bimetallic standard suffered from a dramatic fall in the price of silver and there was no sign of hope for countries maintaining the silver standard or the bimetallic standard. As a result, the rush to the gold standard was accelerated. In our terminology, critical mass for the diffusion of the gold standard was formed in 1875. 6There have been ongoing debates on what constitutes a “region” or “regionalism” in international relations. See Nye (1968), Thompson (1973), Lewis and Wigen (1997), Fawcett (2004), Mansfield and Solingen (2010), and Powers and Goertz (2011). 7One important difference is that the US pursued different strategies towards Asia and Europe. As Hemmer and Katzenstein (2002) elaborate, the US pursued a multilateral approach to European security, epitomized by the formation of NATO, while the US did not seriously explore the similar possibility in Asia. There is no doubt that this factor has influenced the different paths of economic integration taken within Asia and Europe. However, it should also be noted that NATO did not produce the economic integration of Europe that we see today. As discussed by many scholars of European integration, one of the major fault lines in the integration process lies between the Atlanticists, led by the UK, and the Continentalists, led by France and exemplified by the debate on the European Defense Community. 8Readers might find the omission of some important actors such as the US, South Korea, ASEAN members, Benelux countries, and the UK to be problematic. Our rationale for the omission of these actors is as follows. First, the US does not meet the criteria to be considered a “regional” core. In economic matters, the US has always been considered as non-European actor. Although the US successfully constructed a “North Atlantic” region in terms of security area, the US has never asked, and European countries have never invited the US, to be a member of the European economic community. Likewise, the US has engaged actively with Asian countries in areas of security by forming multiple bilateral alliances. However, it was only recently that the US presented itself as an Asia-Pacific or Trans-Pacific player in the economic realm. Second, the omission of South Korea, ASEAN members, Benelux countries, and the UK does not necessarily imply that these countries are less important or less powerful than the chosen “cores.” Instead, the rationale for their omission is the fact that these countries do not have de facto veto power over proposals for regional integration. For example, the UK was not a founding member of the EEC, and France rejected the UK’s application to the EEC in 1963. South Korea became an important player in Asia’s regional economic network only after the 1980s. Benelux countries were founding members of the EEC, but it is difficult to consider them as a coherent bloc on complex issues involving the European process of integration. Likewise, it remains to be seen whether ASEAN members can act as a coherent bloc on complex issues of regional economic cooperation in Asia. 9China imposed conditions on Japan before accepting any negotiation over their normalization treaty in 1972. These conditions, called the “Three Principles,” demanded Japan’s formal approval of the PRC: 1) The government of the People’s Republic of China is the sole and legitimate government of China; 2) Taiwan is an inseparable part of the Chinese territory; and 3) In light of the previous points, the peace treaty between Japan and the Nationalist (Taiwanese) government is illegal and should be abrogated. After succeeding rounds of negotiations, Japan accepted the above principles. 10China was well aware of Soviet ambitions in Asia in normalizing relations with Japan. The PRC strongly insisted on including an anti-hegemony clause in the Sino-Japanese Peace and Friendship Treaty, which stated that China, Japan, nor any third country [USSR] should seek hegemony in Asia. 11For detailed historical and political background see Lee (1979). 12As explained in detail by Moravcsik (1998), West Germany played only a minor role in the early stages of European integration in the 1950s. It was France that played a leading role in that period. For example, the ECSC (European Coal and Steel Community) was proposed by French foreign minister Robert Schuman with the help of Jean Monnet. It was only after West Germany formed a firm and enduring bilateral relationship with France in the 1960s that West Germany played an active role in European integration (which was later hastened by the 1970s German economic miracle). Even during the post-1960s, France, under the presidency of Charles de Gaulle, successfully took the upper hand in the process by executing French veto power over the integration process, as in the case of the Empty Chair Crisis in 1966. Also, though West Germany wanted the UK to join the EEC, the UK was able to join only after Germany successfully convinced France not to veto the admission of the UK.

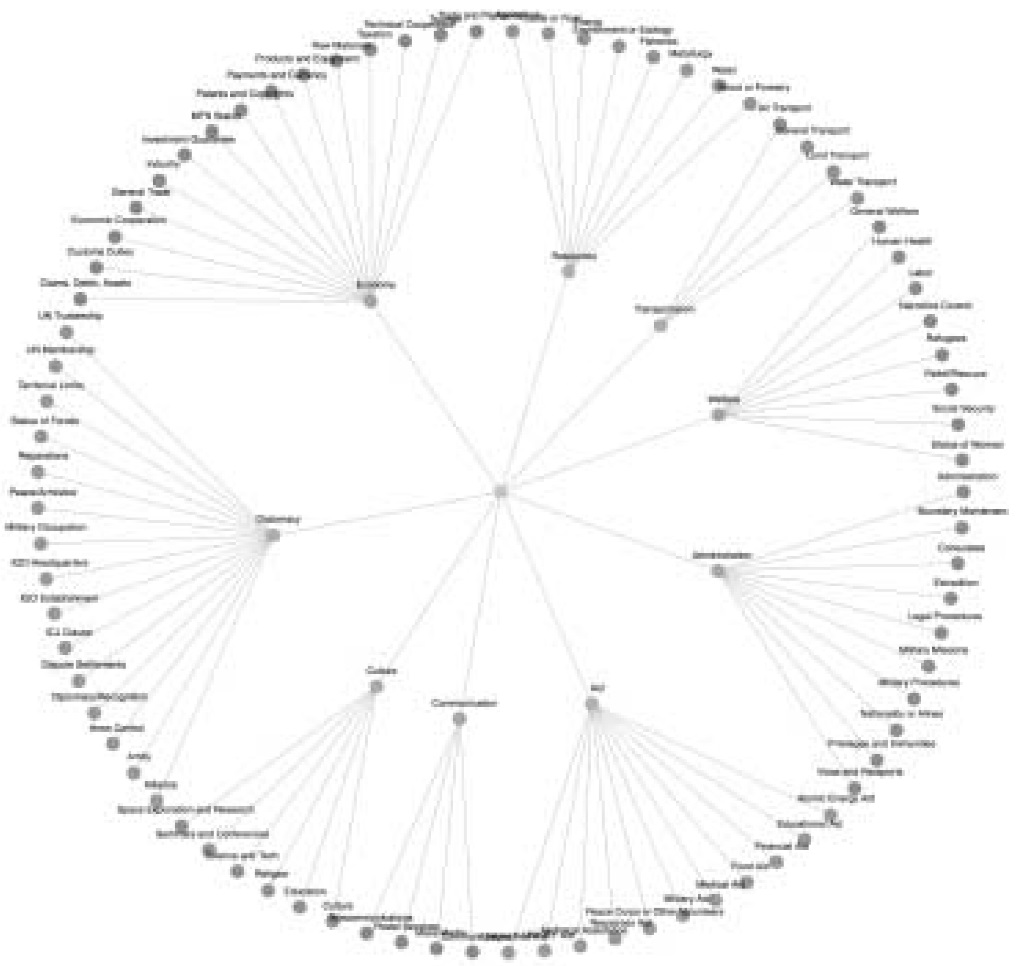

To examine our argument on the role of the ICR in regional integration, we analyze bilateral treaty network data. We collected bilateral treaty data from Peter H. Rohn’s World Treaty Index (Pearson 2001). The World Treaty Index (WTI) is the most comprehensive data source of international treaties. It was first published in 1974, followed by a second edition in 1983. Updates after the second edition are electronically available. In the data set, treaties are categorized into nine domains (Diplomacy, Welfare, Economics, Aid, Transport, Communication, Culture, Resources, and Administration) that are then subdivided into several specific topics. For example, the economy domain contains 15 subtopics (claim, raw materials trade, customs duties, economic cooperation, industry, investment guarantee, most favored nation status, patents and copyrights, payments and currency, products and equipment, taxation, technical cooperation, tourism, general trade, and trade and payments). Figure 2 visualizes treaty domains and corresponding treaty subtopics in the WTI. As shown in Figure 2, the WTI data set classifies all types of registered treaties and covers all registered treaties from 1901 to 2003.

In WTI, states form three types of treaties: multilateral treaties, bilateral treaties, and unilateral declarations. According to the Treaty Handbook published by the United Nations, a “multilateral treaty is an international agreement concluded between three or more subjects of international law, each possessing treaty-making capacity” and a “bilateral treaty is an international agreement concluded between two subjects of international law, each possessing treaty-making capacity.” Unilateral declarations “constitute interpretative, optional or mandatory declarations” (United Nations 2012, 33). Among those treaties included in the index, we chose to analyze bilateral treaties, which constituted 99.6% of all treaties recorded.13

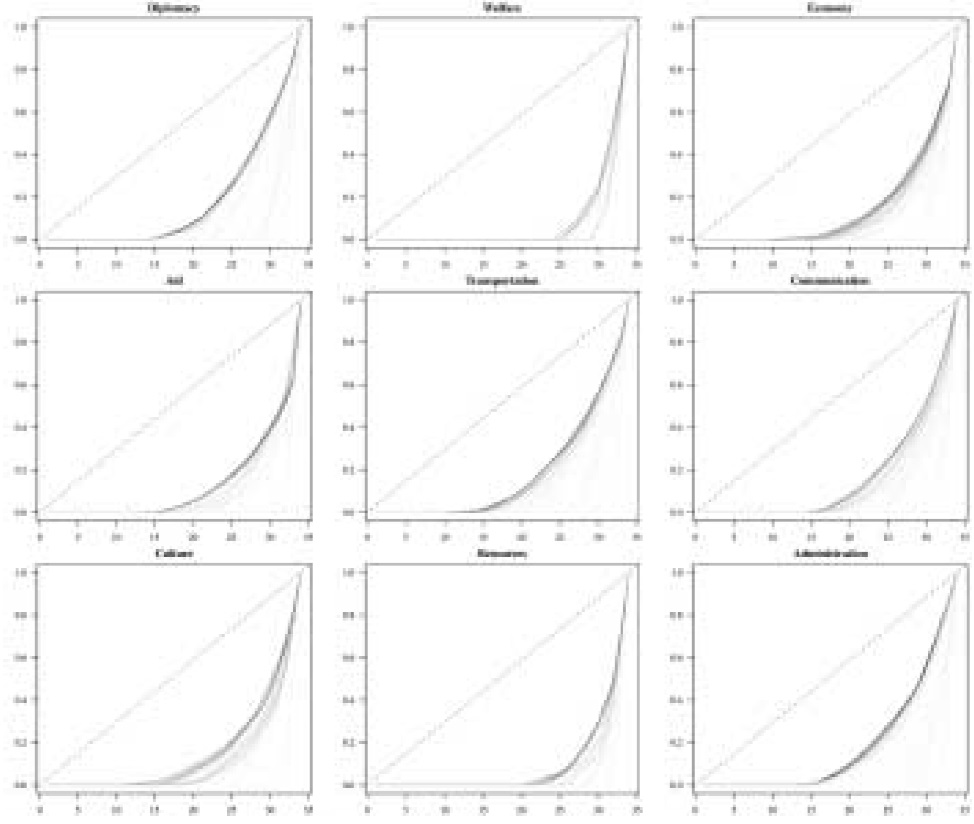

Figure 3 shows the cumulative growth of treaty-joining states across nine treaty domains and 81 subtopics. In this plotting, we make binary annual bilateral treaty network data so country pairs that form more than one treaty in a subtopic are counted to have one bilateral treaty in the subtopic of that year. Numbers in parentheses indicate the total number of treaty-joining states in each subtopic at the end of the sample period. For example, “

Several points in Figure 2 should be noted. First, the growth of treaty-joining states varies a widely across the 81 subtopics. Some of them closely follow the S curve while others show linear growth patterns or just flat patterns. Kernel regression smoother lines (thick solid lines), which show the average shape of growth over time, present as a highly stretched S curve.

Second, the number of treaty-joining countries varies across subtopics. Bilateral treaties on economic cooperation, econ in the top-right panel, have the largest number of joined countries, while bilateral treaties on religion (

Among these bilateral treaty data, we use bilateral treaties on economic cooperation for the analysis because regional integration is essentially an economic process. Also, as shown in Figure 3, treaties on economic cooperation are the most densely connected treaty domain among the nine treaty domains in the World Treaty Index.

We used a community detection method to identify the bloc structures of bilateral economic treaty networks in Asia and Europe. A “community” in a network refers to a group of nodes in which the density of connectedness within the group far outweighs the density of connectedness between groups. Community detection allows us to check whether changes in the relationship between regional cores affect the diffusion of treaty networks at the regional level.

Among the many methods of community detection, we employed the Walktrap measure developed by Latapy (2006). In this method, a walker is placed randomly on a node and moves to a neighboring node based on the following transition probability

In plain words, the above discussion implies that the presence of a cooperative and robust ICR (i.e. if cores of different communities get connected and stay connected for a long period of time) increases the probability of diffusion (community merging). In contrast, the lack of a cooperative and robust ICR (i.e. if cores of different communities stay unconnected and stay unconnected for a long time) decreases the probability of diffusion (community merging).

As mentioned above, we selected France and Germany as regional cores in Europe and China and Japan in Asia. As explained by Cole (2001) and Krotz and Schild (2014), the Franco-German relationship entered into a new era around the time of the Élysée Treaty in 1963. In contrast, China and Japan failed to form a cooperative and robust ICR during the postwar period.

In our analysis, we chose the 28 EU member states for the analysis of the European bilateral treaty network. For Asia, we chose 35 Asian countries, excluding Oceanian countries, Middle East countries, and Cyprus. The full list of country names is available in the Appendix.

13Bilateral treaties have several advantages in the study of the evolution of the international or a regional state system. First, bilateral treaties are more informative about the willingness of cooperation between a pair of countries than multilateral treaties. In bilateral treaties, states freely choose not just the type of treaty but also the contracting party. Thus, the formation of a treaty in a specific issue area indicates the willingness of cooperation among contracting parties involved in that specific issue of interest. In contrast, it is difficult for a state to select only a group of favored states in multilateral treaties. Except for the case of bilateral treaties completely nested within multilateral treaties (Powers et al. 2007), countries have a high level of discretion to join or not to join a bilateral treaty with other states. Second, the formation of a bilateral treaty is a serious commitment among contracting parties. Treaty formation is legal in nature; hence, once formed, treaties impose significant constraints on signatories’ behaviors (Simmons 2000; Koremenos 2005). The forms of constraints vary, though usually they are exhibited in the arbitration of multilateral institutions, direct retaliation, or domestic legal processes. Third, the formation, maintenance, and revision of bilateral treaties are systemic phenomena. Joining a certain type of a bilateral treaty to achieve critical mass generates negative or positive externalities for other countries. Also, a bilateral treaty in one issue area affects the possibility of future agreements on other issues. The complex interdependence of bilateral treaties has been conceptualized as “spillover” (Haas 1961) or “network externalities” (Eichengreen 1996) in the literature. Lastly, once a treaty is formed, it tends to last for a long time. States rarely abandon treaties, but tend to renegotiate or revise treaties once they encounter problems (Pearson 2001, 553). The ‘stickiness’ of treaties is an important characteristic of the modern international system.

ANALYSIS OF BILATERAL ECONOMIC TREATY NETWORKS IN ASIA AND EUROPE

In this section, we analyze different paths of bilateral treaty network evolution in Asia and Europe. Our focus in this analysis is on whether and how inter-core relationships in Asia and Europe have affected the paths of bilateral economic treaty networks captured by changes in the community structure.

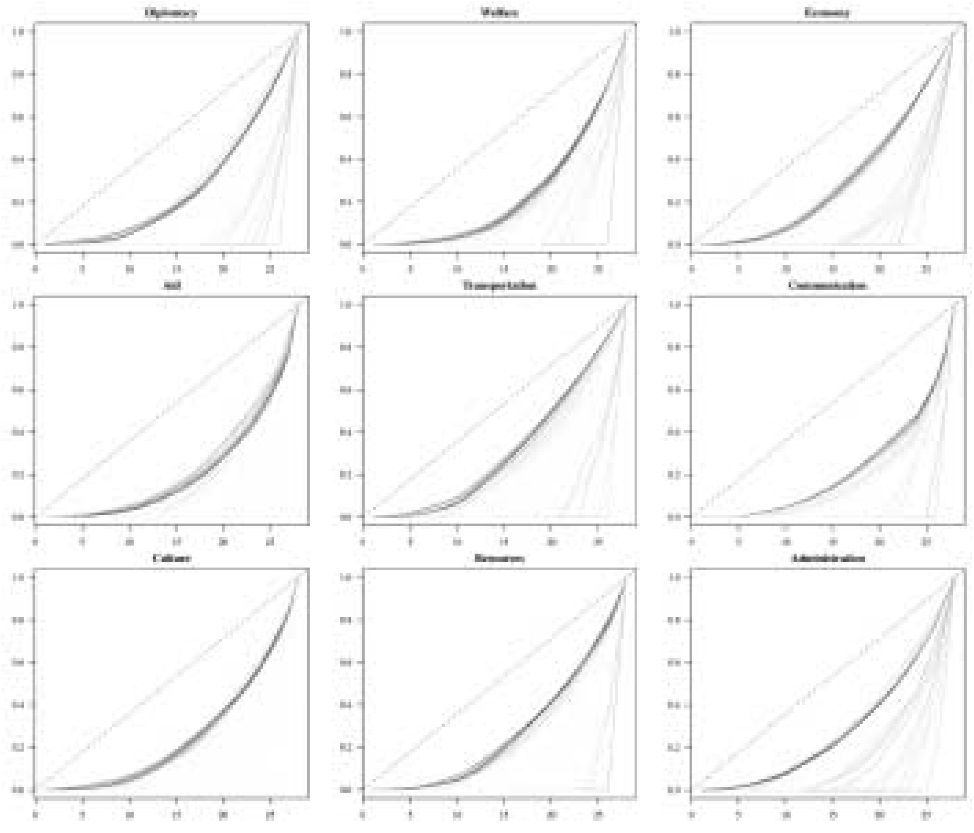

We first show the Lorenz curve of the degree distribution in the bilateral treaty networks of Asia and Europe for all treaty domains. The Lorenz curve is one of most effective ways to investigate the degree densities of multiple networks over a long time span. The more concave the Lorenz curve, the more unequal degree of density the network has. Colors are scaled by time, with darker colors indicating more recent periods and brighter colors indicating earlier periods.

Figure 4 shows that the treaty network in Asia has been highly concentrated in a small number of countries over time and across different treaty domains. The inequality of degree density is particularly notable in two domains: Welfare and Resources. Figure 5 shows a very different picture from Europe. The inequality of degree density is increasingly lower over time across most treaty domains. Recently, the Lorenz curve has become very flat in Economy, Transportation, Resources, and Administration.

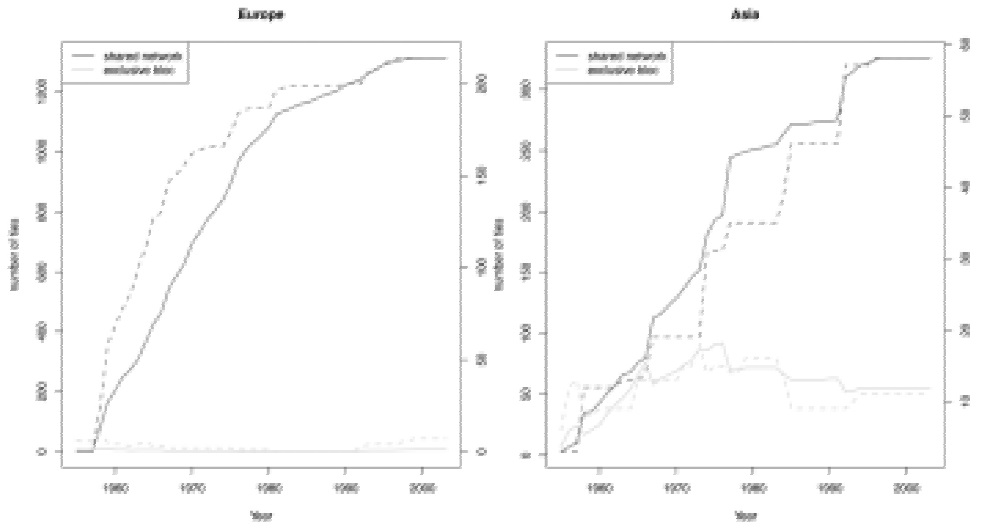

Next, we compare the number of economic treaties that are connected with both cores (shared network) with the number of treaties connected to only one core of the region (exclusive blocs). We expect that the size of the shared network increases from the 1960s in Europe while the size of exclusive blocs stays constantly small in Europe. As we expected, the left panel of Figure 6 (Europe) demonstrates that most European countries are well connected with both cores and the slope increases dramatically in the 1960s and 1970s. Note that there is a small hump in the dotted line around 1991, which indicates the massive inclusion of former communist countries into the bilateral economic treaty network. Some of those Eastern European countries tended to form bilateral economic treaties with either France or Germany, which produced a small hump in the graph. However, throughout the sample period, there is no significant increase in the size of exclusive blocs in Europe, and this pattern shows a dramatic contrast with that of the shared network.

The right panel of Figure 6 (Asia) shows a strikingly different picture. Note that the y-axis of the right panel has different scales compared to the left panel for better display of data. Although our sample of Asia contains a larger number of countries, the total number of ties in Asia is significantly smaller than those within Europe, and the size of the shared network in Asia stays low (under 350 ties) over time. The size of exclusive blocs grows during the 1960s and the early 1970s and remains constant afterwards.

From this analysis, we can see, first, the number of bilateral economic treaties connected with the two cores in Europe grows dramatically in the 1960s and 1970s, while the number of bilateral economic treaties connected with only one core does not rise at all during the same period. Second, the number of bilateral economic treaties connected with the two cores in Asia increases at the same rate with the number of bilateral economic treaties connected with only one core during the 1960s and the early 1970s. Although these patterns are consistent with our expectations, we have yet to see whether the diffusion of bilateral economic treaties in Europe is triggered by the transformation of the Franco-German relationship in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

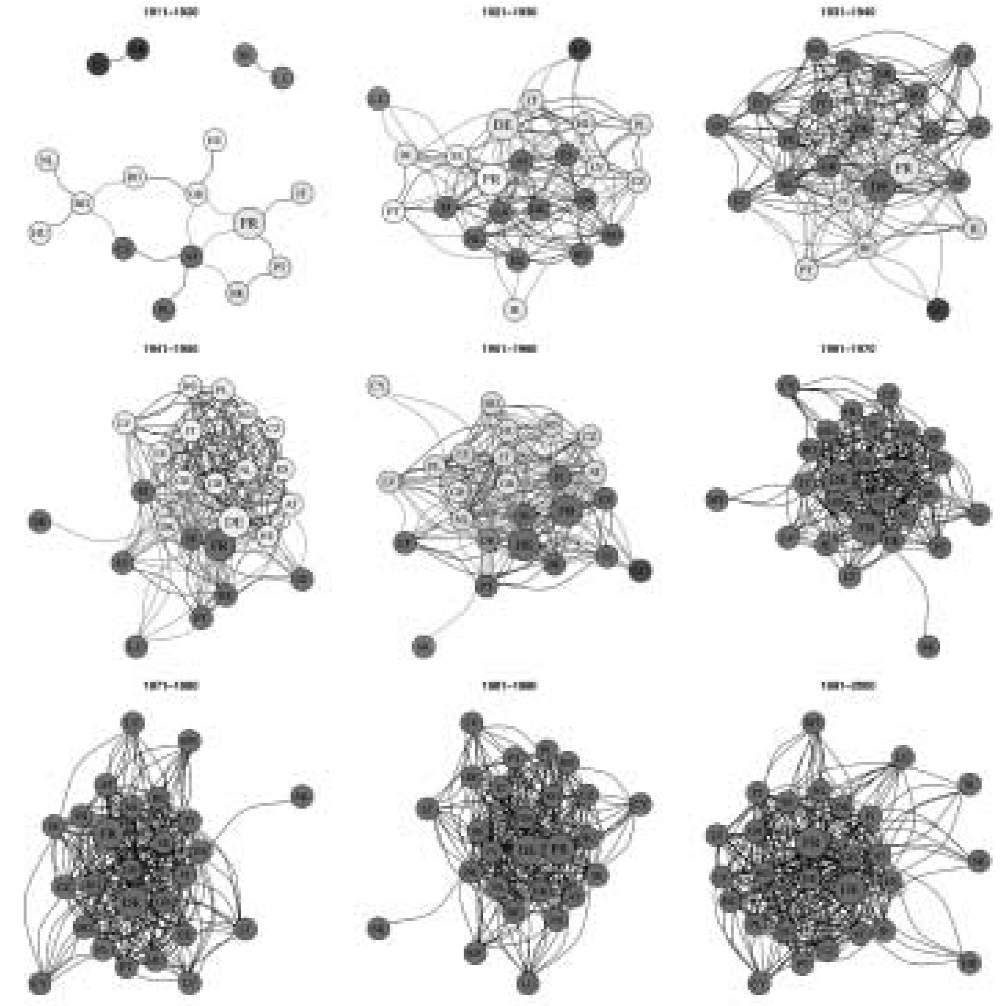

Figure 7 and Figure 8 show the results of community detection analysis for Europe (1911-2000) and Asia (1944-2003). The time frame is different because Asian countries do not have any registered bilateral economic treaties before 1944. Country names are abbreviated by ISO2 codes and reported in the appendix. Different colors indicate different community memberships. Curved edges indicate the presence of bilateral economic treaties. We denote regional cores by a larger node size. Our interest is to check whether changes in the community membership of regional cores are followed by changes in the entire community structure.

The second row of Figure 7 clearly shows major changes in the community structure of bilateral economic treaty networks in Europe. We aggregate annual data into 10-year intervals for better visual presentation.14 As shown in the midcenter panel, the change in the ICR precedes this structural change. That is, after France and Germany were included in the same community in the 1950s, all the countries in the network belong to a single community. If we consider the merging of the community structure as the stage of conquest in the diffusion process, the 1960s can be thought of as the moment of critical mass in the economic integration of Europe. The 1950s has been known as the formative period for the economic integration of Europe with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1951, the establishment of the ECSC, the Treaty of Rome in 1958, and the European Free Trade Association (Britain, Denmark, Norway, Portugal, Spain and Sweden) in 1960. However, our analysis demonstrates that it was the 1960s that produced critical mass for the economic integration of Europe.

If we narrow down the timeframe to a three-year window, as shown in Figure 8, we have a more detailed picture of the transition caused by the change in the ICR. As argued by Cole (2001) and Krotz and Schild (2014), the major changes in the postwar Franco-German relationship occurred between the late 1950s and the early 1960s, epitomized by the 1963 Élysée Treaty. The direct result of this change was increasingly dense economic connections between the two countries during this period. The enduring cooperative relationship between the two countries afterwards, “sealed by a kiss” at the Élysée Palace, generated an important momentum for the economic integration of Europe.

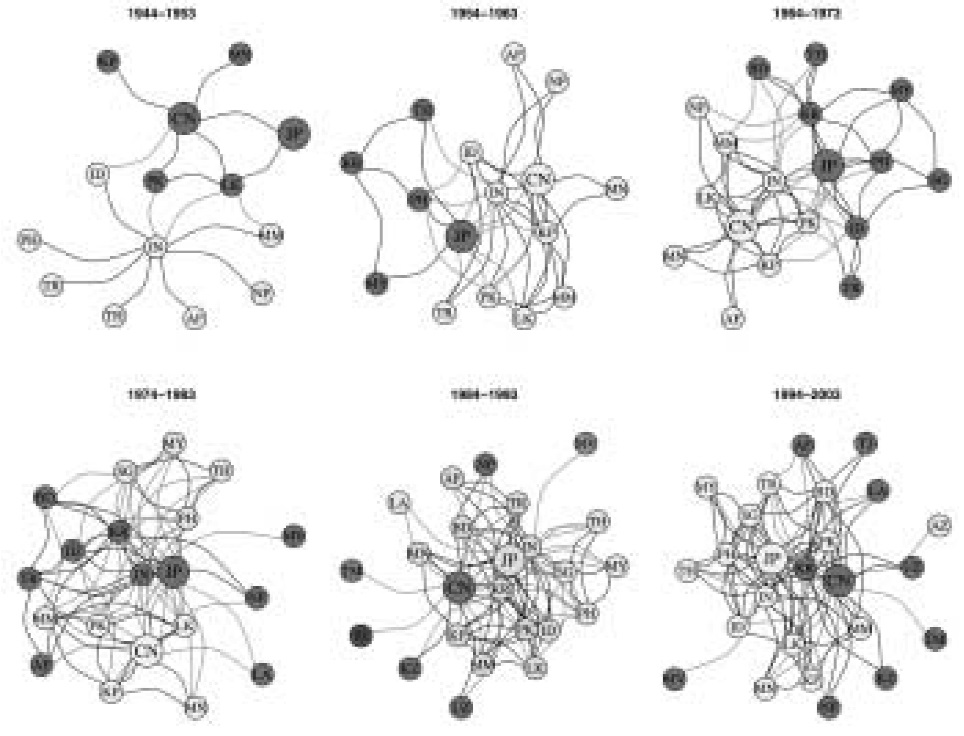

Figure 9 delivers a very different picture of that of Asian economic integration. China and Japan have never belonged to the same community during the 1944 to 2003 period, and China and Japan have maintained their own spheres of influence in the bilateral economic treaty network during the postwar period. Japan has been actively engaging in treaty-making with Southeast Asian countries since the 1970s. China has maintained connections with Central Asian countries.

Note that the bilateral economic treaty network in Asia is sparser than that of Europe’s. Thus, one might argue that the low level of treaty density in Asia is the main reason for the absence of a shared community like the one in European. However, a careful look at the community detection results defies this conjecture. The bottom-right panel of Figure 9 shows the most recent community structure within Asia’s bilateral economic treaty network from 1994 to 2003. We can find that South Korea (KR) and China (CN) belong to the same community, while Japan (JP) still leads her own community. Without a fundamental change in the Sino-Japanese relationship, it is highly unlikely that an increase in the level of network density would bring about the merging of this balkanized economic treaty network structure in Asia.

In Figure 10, we narrow our focus to the 1970s in which China and Japan sought rapprochement, resulting in the 1972 joint communiqu´e and the China-Japan Peace and Friendship Treaty in 1978. The 1970s produced important opportunities for the two Asian cores to transform their bilateral relationship into something closer to a cooperative and robust ICR. Kakuei Tanaka (1972-1974) was chosen Japanese prime minister, and he was willing to apologize for Japan’Øs wartime aggression toward China. Mao Zedong considered Japan a major ally against the Soviet Union and refused to push a claim for reparations for past aggression from Japan (Yahuda 2014, 11). The US was backing Japan to “strengthen its ties with China for the purpose of stabilizing Northeast Asia and counter-balancing the Soviet Union’s appreciable military presence in the entire Asia-Pacific region” (Lee 1979, 432). However, unlike France and West Germany in the 1960s, China and Japan failed to materialize these opportunities in the 1970s into a robust and cooperative relationship, partly due to Mao’s death in 1976 and new negotiations with Deng Xiaoping in which negotiators failed to consider the need for greater institutionalization of the bilateral relationship using regularized summit meetings and ministerial councils, as had happened in Europe after the Élysée Treaty.

This missed opportunity is clearly found in Figure 10. The normalization of the diplomatic relationship between China and Japan in the 1970s did nothing to the community structure of the economic treaty network in Asia. China and Japan had led their own communities throughout the 1970s, and this has not changed up through the end of our sample period (2003).

14If we disaggregate the timeframe further, the patterns become less clear. However, the main conclusion from the analysis does not change: in the European bilateral economic treaty network, the change in the Franco-German relationship precedes changes in the entire community structure in Europe.

Focusing on the formation of bilateral treaties, we provided a network theoretic explanation of the different paths of postwar Asia and postwar Europe. After we proposed a punctuated-equilibrium model of network diffusion that emphasizes the uncertain nature of diffusion dynamics, we argued that successful regional integration hinges crucially on factors that assure a critical mass of countries to embark on a venture promoting a common future without fear of exploitation or noncompliance by regional powers. Focusing on the similarity in regional network structures in Asia and Europe in the early postwar periods, we presented a cooperative and robust ICR as a critical factor that distinguishes the European path from the Asian path throughout the postwar period.

Specifically, we argued that the Sino-Japanese relationship in Asia and the Franco-German relationship in Europe held similar positions but played much different roles in the structure of each regional network. While France and Germany have jointly played “pivotal roles in shaping Europe,” China and Japan have acted like “two tigers” competing to “occupy the same mountain”(Yahuda 2013, 1).

Utilizing the World Treaty Index data set and the community detection method, we found that distinct inter-core relationships in Europe and Asia indeed led to different patterns of evolution in the community structure of the bilateral economic networks between Asian and European countries. The economic bilateral treaty network in Europe merged into a common structure after France and West Germany cemented their relationship constructively and firmly. Although it is difficult to find a direct causal connection from the Franco-German relationship to integration, there are plenty of reasons that support our claim that a cooperative and robust Franco-German relationship fulfilled several functions that served as focal points for European integration. In sharp contrast, the absence of cooperative and robust ICR in Asia led to continuously diverging patterns within the bilateral economic treaty network.

As a prominent postwar historian put it, “If time and space provide the field in which history happens, then, structure and process provide the mechanism” (Gaddis 2002, 35, emphasis original). What we aimed for in this paper was to find a mechanism that explains differences between two fields (Asia and Europe during the postwar period) using a network theoretic perspective. In our reading, previous theories of regional integration did not pay enough attention to relational properties of interstate relationships and thus relied on either oversocialized (e.g. neofunctionalism, constructivism and historical institutionalism) or undersocialized (e.g. intergovernmentalism and realism) concepts to explain the integration process.15 Certainly, a network perspective is a highly simplified view of international relations that only considers ties, nodes, domains, and the history of relationships. However, we believe that for scholars of international relations it is a highly promising theoretical framework that can connect macro-level outcomes such as regional integration and diffusion with micro-level factors such as capabilities, preferences, and identities.

Although the goal of this paper was largely a theoretical one, we would like to note one important implication from our theory and findings. Since 1990, Asia has experienced a wide range of institution building, regional groupings, and identification efforts. The proliferation of regional initiatives for economic cooperation in Asia was caused by many factors, such as the end of the Cold War, the rapid economic development of Asian countries, the common experience of the Asian financial crisis, the rise of China, and the recent “pivot to Asia” by the US. However, despite so many different acronyms representing Asia (e.g. EAEC, APEC, ASEAN+3, ARF, SAARC, SCO, RCEP, and TPP), regional initiatives in Asia have yet to create the critical mass needed to reach the stage of “invasion.”

Based on the theory and findings of this paper, we argue that in order for Asian countries to have the momentum to achieve critical mass, China and Japan should find a mechanism that engenders a long-lasting cooperative relationship. In the Franco-German relationship, it was personal friendship among leaders (de Gaulle-Adenauer, Pompidou-Brandt, Giscard-Schmidt, Mitterand-Kohl, Sarkozy-Merkel, and Hollande-Merkel) and regularized summits and ministerial councils that created enduring cooperation between the two countries. We do not know what will work for the Sino-Japanese relationship in the 21st century, but it is certain that the economic integration of Asia will not go further as long as China and Japan remain two tigers on one mountain.

15We borrow the terms “oversocialized” and “undersocialized” from Granovettor (1985).