The introduction of modern, empirical study methodologies since the twentieth century has led to great advancements in the study of ancient Korean history. The study of ancient Korean history to this point has helped to shed some light on the geographical locations of the Four Han Commanderies (漢四郡 108 BCE–313 CE) and various ancient polities. Moreover, an understanding of the process through which the local groups that emerged during the Bronze Age developed into ancient kingdoms after going through various forms of confederation has also taken root. A more profound perception of the political and social characteristic of the bone-rank (kolp’um) and administrative rank system (kwandŭng) that permeated ancient society has also developed. Light has also been shed on how the centralized royal authority solidified the ruling structure and collected land taxes in local areas through the expansion of local governance organizations. In addition, analyses of the political situation and state of foreign relations in Northeast Asia during the Korean Three Kingdoms Period and the Southern and Northern States Period, as well as studies in the fields of thought centering on Buddhism, have also been conducted.1

The above-mentioned results have been made possible by studies of historical materials in document form such as Samguk sagi (History of the Three Kingdoms), Samguk yusa (Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms), and the official dynastic histories of China and Japan. In addition, recently discovered epigraphs of Paekche and Silla and physical materials uncovered during archeological excavations have greatly helped to advance the field. However, the epigraph materials prepared in ancient Korea should be viewed with a critical eye in that only limited amounts of such sources and other historical materials in document form have been uncovered, and due to the fact that they were recorded based on the perception of readers. Although archeological materials are not subject to the same shortcomings, the accumulation of materials in a particular field is greatly limited by the fact that such findings only shed light on a cultural phase that prevailed at a specific time and place.

The serious lack of materials with which to study ancient Korean history and the many problems with existing materials has been well documented. In this regard, mokkan(wooden slips) can be regarded as an unprecedented material with which to study ancient Korean history. mokkan cannot be distorted or embellished by later generations. They also shed light on various features of ancient people’s cultural life. Although caution should be exercised when using mokkan, they should be viewed as a high quality research material that can break through the limits of existing historical studies on ancient Korea.

The release of collections of script materials, including mokkan(wooden slips), has increased in accordance with the growing number of excavations of mokkan. The following can be regarded as the major collections:2

The emergence of such basic works has led to a rapid increase in the number of studies analyzing administrative documents and the land tax system of ancient Korean society, the ruling system in local areas, as well as the philosophies, religions and rites of the ancient Korean people.3 Domestic and foreign researchers of Korean mokkan(wooden slips) came together to establish the Society for Korean Wooden Tablets. It has published a journal named mokkan kwa muncha [Journal of wooden slips and characters] since 2003, with Volume 10 released in 2013. Major articles and the introduction of newly excavated mokkanmaterials can be found in this journal.

While ancient historical societies in China and Japan have paid attention to the historical value and cultural implications of Korean mokkan,4 Western scholars have generally ignored this topic and few Western studies related to Korean mokkanhave been produced. Although there have been many reasons for this phenomenon, the lack of organized information regarding the current state of the excavation of ancient Korean mokkanand research trends has been singled out as being the primary one. An English language study introducing ancient Korean mokkanwas published recently.5 This has provided useful information with which to analyze general research trends on Korean mokkan.

This study analyzes the characteristics of Korean mokkanin comparison with Chinese and Japanese wooden slips, with a special focus on the types and uses of Korean mokkanmaterials. In addition, the main arguments that have emerged in conjunction with an analysis of the characteristics of the forms of descriptions found on mokkanand the contents of such mokkanis undertaken using several kinds of mokkanso as to represent the different purposes of use. Such an undertaking is expected to further deepen our understanding of the characteristics of ancient Korean mokkanmaterials and to encourage further studies on the use of these mokkanmaterials.

1For more on major study results and future tasks, please refer to the Society for Korean Ancient History, Han’guk kodaesa yŏn’gu ŭi sae tonghyang [New trends in the study of ancient Korean history] (Seoul: Sŏgyŏng munhwasa, 2007) 2The Kaya National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage (http://www.cch.go.kr) provides photos and deciphered characters of ancient Korean mokkan. 3The main findings in this field will be discussed in the text. 4Chinese historians have focused on the mokkan on which the Analects of Confucius were written discovered at the site of the Lelang Commandery, in Kimhae and in Inch’ŏn. Meanwhile, Japanese scholars have paid attention to the process whereby the culture of Chinese characters was accepted in Japan via the Korean peninsula and the relationship between ancient Korean and Japanese wooden slips. They have also conducted comparative studies of the two countries. 5Chŏn Tŏkchae, “Materials and Trends in the Study of Ancient Korean Wooden Slips,” The Review of Korean Studies Vol. 15 No. 1 (2012).

mokkan (木簡, wooden slips) are wooden tablets that feature writings, signs, or drawings. Long and rectangular in shape, they resemble the wooden rulers used in ancient Korea. While they are generally 20 cm in length and 2.5 cm in width, their size varies, with one even estimated to be 1.2 m long. While pine, willow, oak, chestnut, and sometimes linden were used to make mokkan, bamboo was rarely used on the Korean peninsula.

In China, these tablets are called jiandu (簡牘), and are separated into zhujian (竹簡, bamboo slips) and mudu (木牘, wooden slips). zhujian are made of bamboo, whereas mudu are made of other tree species (Li Junming. 2003, 135–144). The shape of the mokkanof ancient Korea is similar to that of the zhujinan. However, the species of tree employed is generally not bamboo. So it is called mokkanin Korea.

The term mokkan(木簡) appears in literature produced during the thirteenth century in which traditional narratives related to ancient history and Buddhism are collected.

This traditional narrative recounts the situation of Silla at the end of the ninth century, However, the term 木簡 was also used in China. It is also found in Yan Shigu’s annotations of the Hanshu (漢書, Book of Han).

The wooden slips used for recording purposes were called mujian (木簡) in China prior to the Tang dynasty (Tono Haruyuki. June 1983). The term mokkanor mujian (木簡, wooden slips) was widely used in East Asian society during the pre-modern period (Yun Sŏnt’ae, 2007, 37). Japanese scholars also used the term mokkan(木簡). Based on this reality, the present study will refer to the wooden tablets made of trimmings and refined wood materials on which one could record or draw something as mokkanor mokkanslips.9

Based on their contents and functions, mokkancan be classified as follows: scriptures (Confucian classics and Buddhist sutras); documents (reports, messages, ledgers, and daily logs); tags (names and shipping lists); rituals (charms, orations, and human-shaped slips); memos (verses and drafts); and mokkanfor practice purposes (letters, calligraphy and drawings).

mokkan used for scriptures include the collection of bamboo slips (zhujian) excavated in Chŏngbaek-tong, P’yŏngyang. This zhujian depicting a Confucian classic was used during the first century BC in the Lelang Commandery.10 It is composed of over 100 pieces of bamboo slips that are connected to each other by string. The Buddhist sutra which was discovered at the Hwangbok Monastery site in Kyŏngju is also made of bamboo slips, thus raising the possibility that it was produced in China before being imported to Silla. On the other hand, the mokkanslips of the Analects of Confucius discovered in Kyeyang Fortress in Inch’ŏn and Ponghwangdae in Kimhae were made of pine. Unlike the scriptures produced in China, these slips have a long bar shape of over 120 cm in length and are multi-sided. Some have argued that these slips were made for practice purposes (Hashimoto Shigeru, 2007) and that their differences can be attributed to the fact that they were produced for examination purposes (Lee Sungsi, 2009). The possibility also exists that scriptures were produced as bound mokkanin ancient Korea.

mokkan used for documents were produced as part of the administrative process. This category included reports, messages, ledgers and daily logs. The mokkanused for tagging purposes were employed to mark storage containers and keys; meanwhile, shipping lists were used to transport freight. mokkan used for rituals were utilized to conduct various religious events and ceremonies. mokkan used for memos were generally drafts of official documents and phrases. These had similarities to the mokkanused for practice purposes in that they were used to write down ideas when they came to mind. The mokkanused for practice purposes were used to practice writing and drawing.

6Samguk yusa (Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms) Vol. 2. Wonder 2. Queen Chinsŏng and Kŏtaji. 7Hanshu (漢書, Book of Han) Vol. 1. Annals of Emperor Gaozu. Part 2 8Hanshu (漢書, Book of Han) Vol. 57. Sima Xiangru Part 1 9However, the name and concept of Korean mokkan could be altered if new artifacts made of bamboo or with shapes similar to wide mudu such as fang 方 were to appear in the future. 10The Lelang Commandery was one of the local bodies installed by the Han dynasty of China following the destruction of Kojosŏn or Old Chosŏn located in the northwest of the Korean peninsula from 108 BCE to 313 CE. Strictly speaking, the mokkan slips of the Lelang Commandery were Chinese artifacts. However, the author has treatesd them as belonging to the category of Korean mokkan because they were excavated on the Korean peninsula and the residents of Kojosŏn participated in the ruling structure of the Lelang Commandery as officials of Lelang.

The actual study on Korean mokkanstarted in 1975 when over 100 mokkanslips were uncovered in Anap Pond in Kyŏngju. Another chance to develop research arrived with the discovery of the mokkanat Sŏngsan Fortress in Haman. Having the largest number of items among the sites unearthed hitherto, the mokkanexcavated in Haman are for the most part uniform in shape, size and function. The Sŏngsan Fortress mokkanmay have statistical implications. This has made it possible to obtain critical facts about the system of supplies and tax institutions from this series of shipping tags.

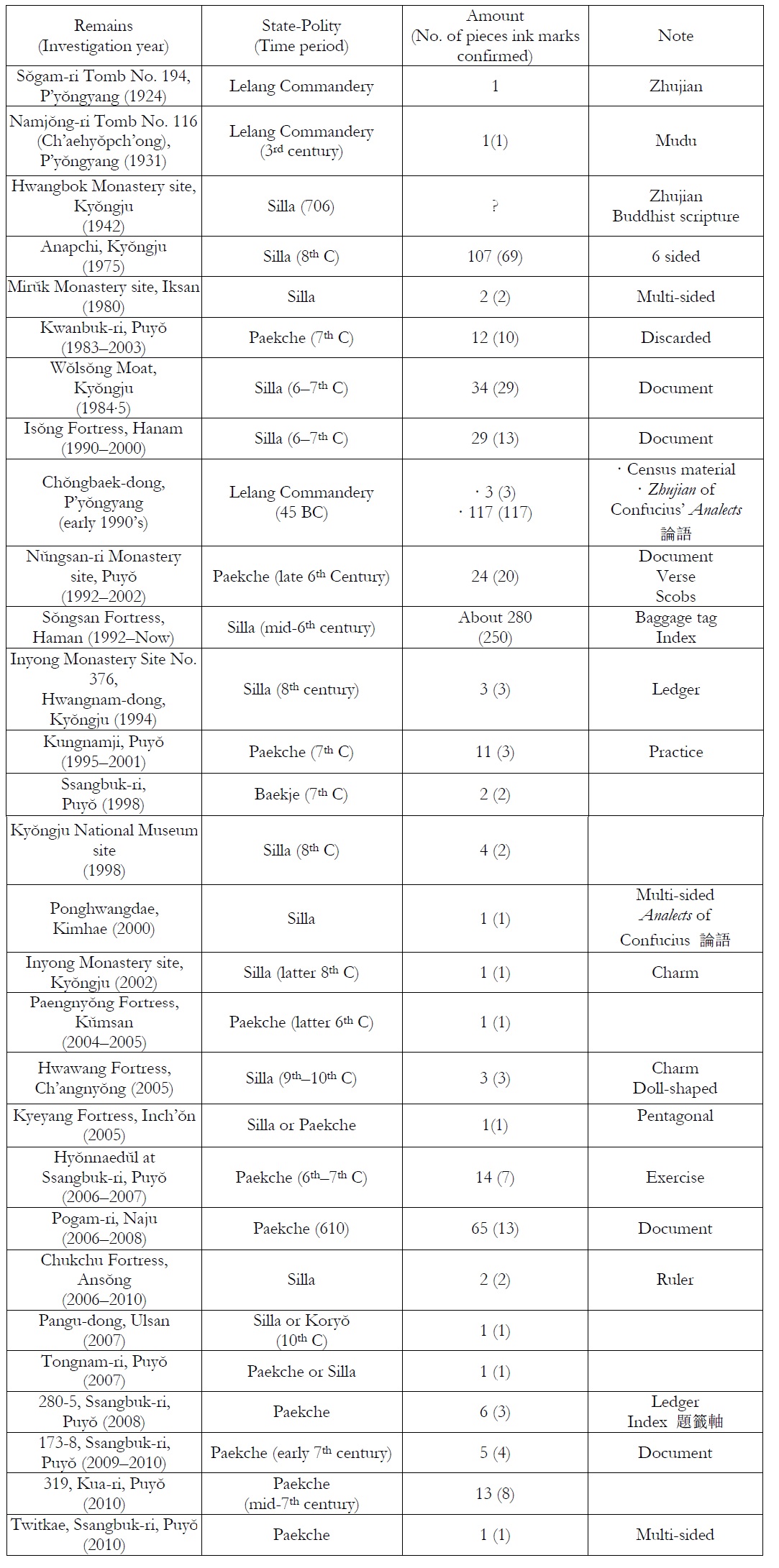

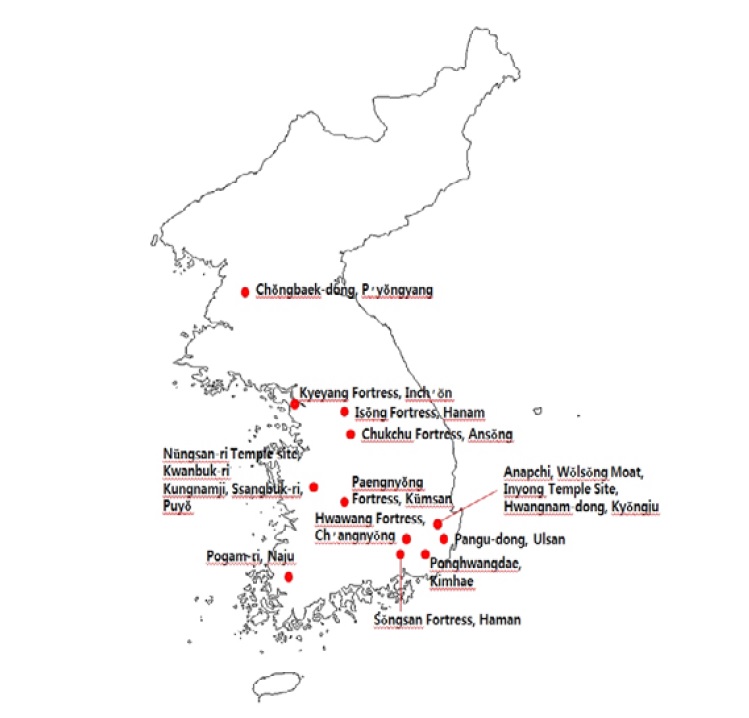

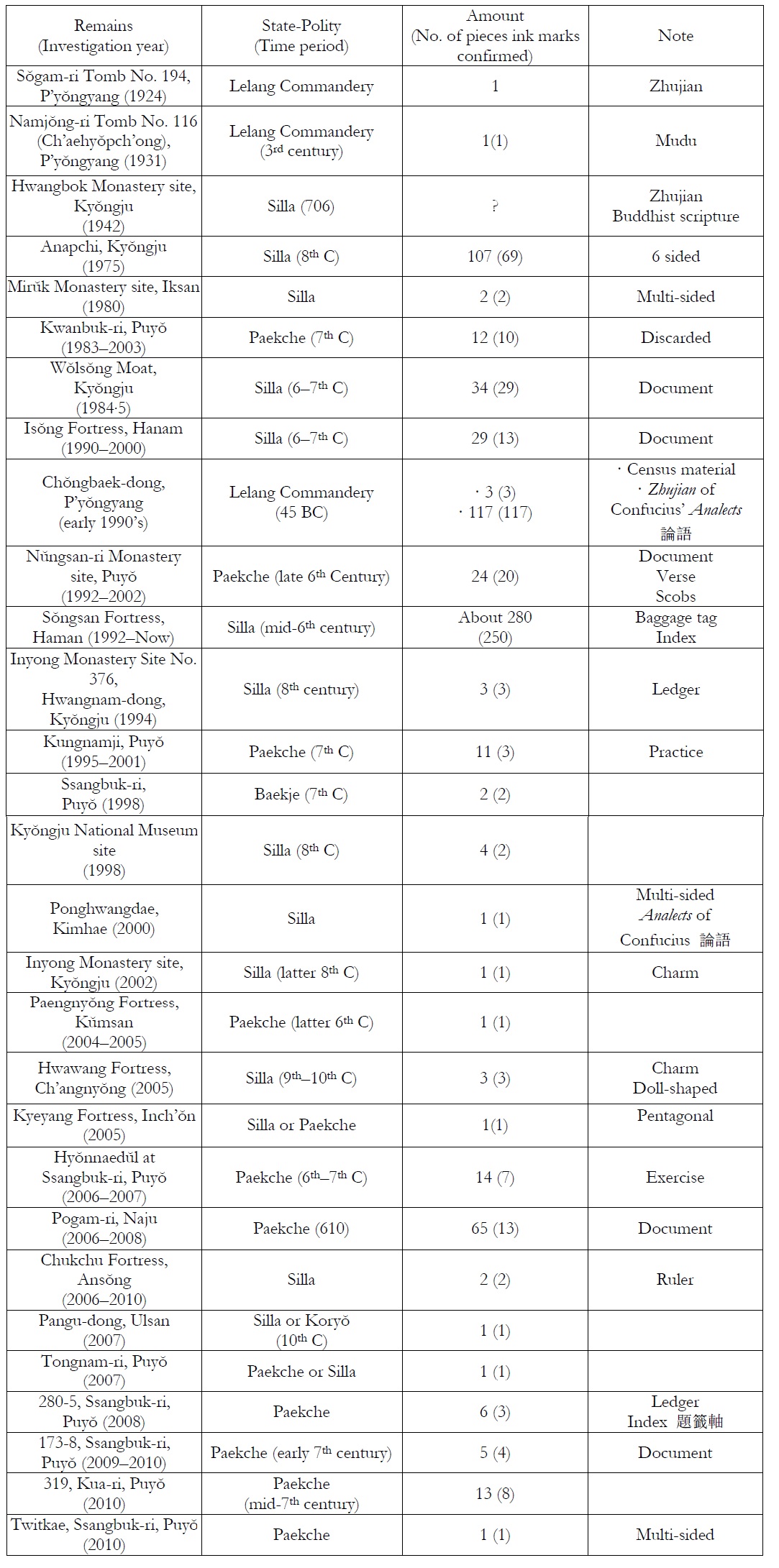

mokkan have been excavated every year since the 1990s, with some 700 pieces having been uncovered from twenty-seven sites as of 2011. These items were produced by the Lelang Commandery, Paekche and Silla. A look at the location of the sites where mokkanhave been uncovered reveals that the majority have been unearthed in the southern part of the Korean peninsula. This is because most mokkanwere uncovered among remains from Paekche and Silla. While mokkanfrom Koguryŏ, Kaya and other polities have yet to be found, there is a strong possibility that such items will in fact be discovered in the future.11 Table 1 shows the current state of mokkanexcavation on a chronological basis.

Some of the above-mentioned cases can be regarded as representative types and usages of ancient Korean mokkan. A piece of a bamboo slip (zhujian) was discovered from an ancient tomb of the Lelang Commandery located in Sŏgam-ri, P’yŏngyang in 1924. This was the first Korean mokkanmaterial uncovered in an excavation. This bamboo slip was 23 cm long and 1 cm wide, the standard size for bamboo slips in the Han dynasty. The surface of the bamboo slip was varnished with lacquer. Although there are no characters engraved on the slip, it is estimated to be a cover of a book as a binding mark remains (An Kyŏngsuk, 2013).

Buddhist sutra zhujian have been claimed to have been found at Hwangbok Monastery during the Japanese colonial period. However, few details have been brought to light about these artifacts. The mokkanfrom the Kwanbuk-ri site stands as a salient example of how such items were discarded after they had been used. It was cut into parts along the wood grain (Yi Yonghyŏn 1999, 342). A document found among the mokkanslips uncovered at Wŏlsŏng Moat contains an order given by an official to buy pieces of paper. The order and report on its execution were written on the four faces of this particular mokkan(Yi Sŏngsi 2002, 30).

Scobs are fragments or scraps formed in the process of taking off the surface of a mokkanwith a blade. Scobs uncovered at the Nŭngsan-ri Monastery site show that much as pencil marks are erased by an eraser today mokkan could be revised or re-used after the written surface had been scraped off with a knife.

An index mokkan called chech’ŏmch’uk was uncovered at Sŏngsan Fortress. Bookmark-shaped, it was intended to be affixed to the end of a paper with the name of the document at the top. People used it to tell and find the roll they were looking for without unrolling them. As such, these index mokkancan be seen as evidence that paper documents were used in the middle of the sixth century in Silla.

A mokkanused for practicing the calligraphy of the character wen (文) was excavated from the Kungnam Pond site. Some mokkanslips contain verses as well. Though written in old Chinese sentences, the grammatical order and word usage include a mixture of Korean elements (Kim Yŏnguk 2003; Yi Sŭngjae 2012). This can be construed as meaning that people were able to create, copy, or extract these poem so as to annotate them.

One of the mokkanexcavated from the 280-5, Ssangbuk-ri site in Puyŏ is believed to be a kind of ledger. Paekche officials prepared this type of ledger so that they could transcribe the amount of principal and interest that was involved, and whether the amount had been fully refunded. Based on these figures, we can surmise out that the rate of interest was 50% (Mikami Yoshitaka 2013, 196).

Photographic evidence of zhujian and mudu from the Lelang Commandery recently uncovered at a tomb in Chŏngbaek-tong, P’yŏngyang (Lee Sungsi, Yun Yonggu and Kim Kyŏngho 2012) has recently surfaced. Despite reports of the discovery of jiandu such as a mudu from Ch’aehyŏpch’ong Tomb during the Japanese colonial period, no detailed information has to date been forthcoming about such items.

However, even these partial materials have provided us with some important facts. For instance, while the Chŏngbaek-tong zhujian contained the Analects of Confucius, the mudu were the records of statistics on household, population and their changes. Considering the shape and the binding method, we can conclude that the zhujian of the Analects of Confucius arrived on the Korean peninsula from China during the Han dynasty. The mudu must have been used by an official of the Lelang Commandery that ruled over the people of former Old Chosŏn, who had been buried in that tomb. It is clear that the recording and writing systems of ancient China were the precursors of those of ancient Korean society.

But the mokkanculture of ancient Korea was not initiated solely by the import of the Chinese writing system. Rather, a traditional system of indigenous communication already existed in ancient Korean society. This was an important element in terms of the selection and acceptance of Chinese culture by ancient Koreans. Let us take a look at the following record.

The veracity of this record can be called into question. As the Silla Monument in Chungsŏng-ri in P’ohang, on which Chinese characters were engraved, was established prior to 501, it should be regarded that the culture of Chinese characters had already been introduced to Silla society before the fifth century. As such, this record should not be construed to mean that the people of Silla were completely unaware of Chinese characters. Rather, the usage of Chinese characters should be seen as having been less pronounced in Silla than in Koguryŏ and Paekche. At the time, Silla envoys visited the Liang dynasty of China along with Paekche envoys. The Silla envoys could only communicate with Liang through the Paekche envoys. Under such circumstances, there is a possibility that Paekche purposefully misrepresented the culture of Silla to Liang.

Anyhow, according to the above records, Silla was unaware of Chinese characters around 521, and used a piece of wood on which signs were inscribed as a kind of token of trust. Thus, the people of Silla used a piece of wood to deliver information even before they knew Chinese characters.

The mokkanculture of ancient Korea was formed by the acceptance of the Chinese writing system on top of existing indigenous communication methods. In addition, the differences between Chinese jiandu and Korean mokkancan be traced back to this factor.

11This possibility is further heightened by the image of an official named Kisil depicted in a mural painting in No. 3 tomb in Anak of Koguryŏ, in which he is holding a brush and a mokkan in his hands. Kisil was a scribe in charge of transcription. In addition, five ink brushes and a small knife were found among the artifacts of Taho-ri Tombs in Ch’angwŏn. This region was home to the Pyŏnhan polities that subsequently developed into the Kaya confederation. 12Liangshu (梁書, The book of Liang) Vol. 54 Liezhuan (列傳, Biographies) 48. Silla

Having introduced ancient mokkanKorean above, I will now present a brief summary of mokkanslips and explain their features and usages. Examples include mokkanfrom Sŏngsan Fortress in Haman, mokkanfrom Pogam-ri in Naju, and mokkanfrom Hwawang Fortress in Ch’angnyŏng. These mokkanslips on which recent studies have been based exhibit the diversity of ancient Korean mokkanand have been used to shed light on new facts related to epigraphs and historical materials presented in document form.

As Haman was a central region of Ara Kaya, the main tombs of this kingdom, namely the Tohang-ri and Malsan-ri tombs, were located north of Sŏngsan Fortress. However, the fortress itself was built by Silla around 561, or after Ara Kaya had fallen. The mokkanslips were found in a small mound between wooden fences made to facilitate drainage inside the fortress walls (Pak Chongik 2000).

A closer look at the shape of these mokkanshows that they have two grooves facing each other as well as a small hole on one side. People tied a string that hooked into these indentations or was passed through a hole to attach the mokkanto items of baggage that contained grains such as millet or barley that served as tax. These taxes were collected from several regions in the northern part of Kyŏngsang and Ch’ungch’ŏng Province. Around 561, Sangju was a local district governing that area. People who lived in areas such as Kuribŏl and Kammun dispatched their taxes to this fortress across an overland path or via the Naktong River (Yun Sŏnt’ae 1999; Yi Yonghyŏn 2006). Such supplies were used as rations for laborers and the military at Sŏngsan Fortress (Yi Kyŏngsŏp 2013, 135–141).

So-called noin (奴人) mokkanwere discovered among these remains. They contained the character noin (奴人) or just no (奴) in their texts. Interestingly, the word noin ends with the character chi (支) and the last part of the transcription ends in pu (負), which means “a baggage transported to other places” (Yi Suhun 2004) or “to carry something on one’s back” (Chŏn Tŏkchae 2007).

The entry on the noin mokkanreads “a kongmin (公民, commoner)’s name, rank - no(in) 奴(人) – noin’s name – way of transport.” This entry as such would seem to be related to how a person living in a certain area paid his taxes. That being the case, the question becomes, who paid taxes, citizens (including commoners) or noin? Were noin private slaves akin to nobi (奴婢), or something else? Scholars who regard noin as nobi argue that special social groups such as newly conquered subordinates or different ethnic groups had all but disappeared in the 530s (Chŏn Tŏkchae 2002, 222–232). According to this view, most people of Silla were citizens and only nobi remained as subordinates in that period and thereafter. As such, noin must inevitably be construed as another name for nobi who transported taxes on their owner’s behalf.

However, there are some problems with this private slave theory. First, no (奴) was used to denote a sense of contempt or self-humbling. For instance, nogaek (奴客) means a tenuous state or a paltry person.13 No did not solely mean “slave.” Therefore, noin is a composite of no (奴) and human being (人), and implies that its nature lies somewhere in the middle between humans and non-human beings such as slaves. If noin were no more than private subordinates, then why did the officials write their names on the mokkanwhen the owner’s name had already been entered in the upper part? Moreover, names ending with the character chi(支) do not reflect nobi status. Rather, chi has been used in conjunction with the names of commoners or potentates such as settlement authority (ch’onju 村主).14 A look at the ratio of noin in Kuribŏl, which was one of the areas providing supplies to Sŏngsan Fortress, reveals that roughly 30% of the population belonged to this class of individual. This percentage is much higher than the general portion of the population of nobi (5.6%) listed in the Silla Village Documents (Silla ch’ollak munsŏ 新羅村落文書) (Hatada 1976 Takashi 1976, 444–446).

In my view, the term noin did not refer to private slaves but members of collective subordinates. The terms, noin and Noin Law (Noinbŏp 奴人法) appear on the Pongp’yŏng Silla Stele in Ulchin that was erected in 524. The residents of Koguryŏ in the Ulchin region, whose ethnicity might have been Ye (濊), became noin of Silla after the latter’s conquest of this area. In order to rule and control these individuals, the Noin Law was legislated in the administrative code in 520. Thus, the social character of the noin mentioned in the mokkanslips of Sŏngsan Fortress should be seen as being related to those described in the Pongp’yŏng Silla Stele that was erected in Ulchin (Pak Chonggi 2006).

I believe the noin referred to on the mokkanslips were also collective subordinates that originated from different ethnicities or polities. However, they had a duty to transport taxes to Sŏngsan Fortress in Haman (Hirakawa Minami 2007). The Silla state implemented a policy designed to alter the character of the noin from ethnic subordinates to citizens of Silla by means of such mobilizations or military service. In addition, the noin were assigned to live alongside citizens living in general districts like Kuribŏl not in special areas like the noin Village(奴人村) referred to in the Pongp’yŏng Silla Stele. Such steps were taken for control purposes. That is why the name of the citizen was also included in these mokkan(Kim Ch’angsŏk).

Assertions have recently been made that the term noin (奴人) found on the mokkanslips of Sŏngsan Fortress in fact referred to private slaves. Private slaves (sanobi) were as such seen as having to pay taxes to the state in Silla because they transported freight (Yun Sŏnt’ae 2012).15 It has generally been accepted that while slaves were not protected under the national code because of their social status as lowborn, they were in fact exempt from having to shoulder any of the state’s taxation burden. Thus, the above assertion involves a fundamental reexamination of the social and economic character of slaves (nobi). In this regard, it becomes necessary to analyze the description methods employed in the Silla Village Documents (新羅村落文書). The Silla Village Documents included not only the number of nobi (奴婢) but also the ages of the able-bodied adults (chŏng 丁) and able-bodied women (chŏngnyŏ 丁女) who had reached retirement age within the village. However, there is no clear-cut mention of slaves (nobi) being subject to tax collection in this record. It only recorded the number of males who belonged to the chŏng (丁) category or or those of retirement age and then separately inscribed the number of no (奴) within the chŏng (丁) category. If Silla perceived the slaves or nobi (奴婢) as being subject to tax collection, then the description method should refer to the “number of chŏng (丁) among the no (奴), and the number of cho (助) or age rank.” It is believed that the same criteria applied to the nobi (奴婢) and commoners when it came to measuring age and value of property, but not with regards to tax collection. Samguk sagi (History of the Three Kingdoms) includes an entry stating that the no (奴) of Hapchŏl or Nulch’oe participated in a war. However, this in essence amounted to these individuals bearing the responsibility to participate in such wars on behalf of their owners (Yi Kibaek 1977, 8).

Let us take a look at the Paekche mokkanslips uncovered in Pogam-ri. While the mokkanslips of Sŏngsan Fortress were produced within local society in Silla, the mokkanslips discovered in Pogam-ri, Naju, South Chŏlla Province can be regarded as products of Paekche local society. However, these were used for different purposes. Whereas the majority of the mokkanslips of Sŏngsan Fortress were baggage tags, the mokkanslips of Pogam-ri were composed of various documents used to govern and administrate the local area.

The Pogam-ri area of Naju is regarded as having been one of the central regions of the Mahan confederation. However, from the sixth century onwards, Paekche exercised bureaucratic and military control over the area. The mokkanfrom the Pogam-ri site in Naju constitute evidence of the direct administrative control system that Paekche exercised over local areas. As the Pogam-ri site is located in the vicinity of the Yŏngsan River, the Hoejin Fortress, the settlement remains of Nang-dong, the earthenware kiln remains of Oryang-dong, and several tomb complexes, there is a strong likelihood that the local government office might have been in the vicinity.

The site consists of a few remains such as an iron production facility, a ritual involving a sacrificed cow, a dwelling, and a water storage facility. Sixty-five mokkanslips were discovered in a 4.8 m deep pit believed to have served as a water storage facility for iron production. Excavators have identified that Layer II, which included the mokkanslips, formed between the end of the sixth century–early seventh century (Kim Hyejŏng 2010). Therefore, the reference to the Kyŏngo Year (庚午年) found on mokkan No. 11 would seem to denote the year 610, which occurred during the reign of King Mu.

This is also confirmed by references to the local government system of kun (郡, county) on mokkan Nos. 4 and 10. The county (郡, kun) system was established no later than the Sabi Period (538–660 CE) and was abolished under the control of the Area Command of Xiongjin (熊津都督府) established by the Tang dynasty in 660 (No Chungguk 1988, 247–262). Earthenware featuring the word “Tuhilsa” (豆肹舍) was excavated from the same layer of the pit where the mokkanwere found. This would seem to indicate that the region of Pogam-ri was known as Tuhil (豆肹), and was under the control of Palla-kun located in what is now Naju City. The name of this locality and administrative system coincide with the description found in a written document.16

Even though mokkan No. 2 only contains a few vague characters, one can clearly make out those of chŏngjŏng (正丁) and pu (婦). This is an important research material insofar as it provides some much needed insight into the composition of kinship in Paekche society. Characters such as those for elder brother hyŏng (兄), elder cousin chonghyŏng (從兄), wife pu (婦) and younger sister mae (妹) included in these mokkanslips all refer to relatives. Additionally, the age group, job category, and the number of people who belonged to that age rank were attached to the record for the relevant person.

This slip was damaged and the upper part on which entries related to the head of the household, the younger brother, and his family, were entered has been lost. This section may also have contained records pertaining to other families. As such, this household would appear to have been composed of several families. For instance, the elder brother’s family may have been composed of the elder brother himself, his two wives and four children. In terms of its form and contents, mokkan No. 2 is a ledger or kind of census pertaining to the overall composition of a household. In this particular instance, the number of chunggu (中口) was found to have increased. All these facts were confirmed by another official who wrote the character chŏng (定) at the end of the mokkan (Kim Sŏngbŏm 2010).

mokkan No. 5 contains a wide range of information. On the front side, one finds the names of a village, the head of a family, and details regarding corvée labor such as the domestication of animals. It is the conjecture of this article’s author that the resources introduced on the backside were related to the cultivation of land.

The fact that the mokkanfrom the Kungnam Pond site in Puyŏ has a similar figure, writing form, and contents as Pogam-ri mokkan No. 5 is highly interesting.17 The land measuring unit hyŏng (形) was also used in both mokkanslips. Additionally, mokkan No. 5 has a transcription pertaining to the kinds of farmland, namely rice paddies, dry fields, and barley fields. Furthermore, the yield from these fields and amount of labor days were also entered. So, both of these two mokkan strips were made as ledgers for labor requisition. Moreover, I believe these lands were owned by the local government office (Tuhilsa) and Maera Fortress. This is why these labor resources could be mobilized to cultivate the land (Kim Changsŏk 2011).

There are other mokkanrelevant to labor requisition. A look at Mokkan No. 3 reveals the period and regions—certain Mora, and Panna, a region in present-day Pannam-myŏn—where people were assigned, the kind of work they were expected to carry out and other elements on the front side. Meanwhile, the back side contains details about the labor in question. In the upper part are entries related to “craftsmen specializing in wall building” (比高墻人), and in the lower part the names and ranks of persons in charge of control over craftsmen. Mokkan No. 1 is believed to be a report on an incident involving the arrest of “fugitives” (出背者). They may have been recruited for military service or corvée labor such as iron producing. They tried to escape this labor by running away to Tŭgan Fortress, currently Eŭnjin, Ch’ungnam Province, but were eventually arrested.

As mentioned above, we can surmise that by the early seventh century the Paekche state had established an administration system to rule over local societies, and this even in the remote southwestern area of its territory. The terms and their designations of kun (郡), sŏng (城), ch’on (村) are found in the Pogam-ri mokkanreferring to the pang (方) kun (郡) sŏng (城) local ruling system. This administrative power could have reached all the way down to the household and even individual level, facilitating control of the people and the collection of taxes(Yi Sŏngsi 2010).

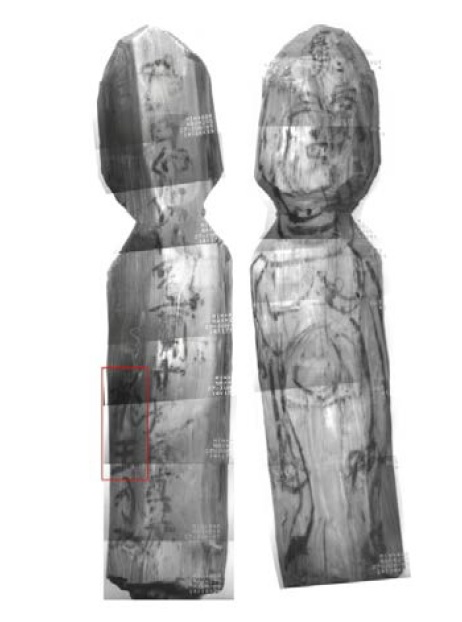

The next series of mokkanthat we will look at are those taken from the Hwawang Fortress in Ch’angnyŏng, whose contents and usage have proved to be the subject of controversy. Seven mokkanpieces were discovered along with pottery vessels and iron tools among the remains of a reservoir on top of Mt. Hwawang.

As this mokkanlooks like a human-shaped doll, it can provide us with more information than regular ones. It is 49.1 cm high, with writing on the front side and a woman figure on the back. Excavators believe it may have been made in the ninth–tenth century, a period that coincides with the end of Unified Silla and the beginning of the Koryŏ period. Some of the characters have proven difficult to identify and decipher (Pak Sŏngch’ŏn and Kim Sihwan 2009).

This mokkanhas two particular factors that have attracted attention. First, it was uncovered in a reservoir where people believed the dragon king lived. The second is that six nails were found on the woman figure’s body, namely on top of the head and neck, on both breasts and on both hands.18 The question thus becomes, why were nails driven into this mokkanand why was it thrown into a reservoir?

There have been two prevailing opinions concerning this. The first is that the people’s objective was to pray for rain (Kim Chaehong 2009; Mikami Yoshitaka 2013). One scholar has argued that the woman was a shaman who proved unable to secure sufficient amounts of rain. As such, the mokkanwas offered instead of her to the Dragon King believed to oversee rain. Moreover, the nails were driven into the body as part of a sacrifice (Kim Chaehong 2009).

However, there are some problems with this line of reasoning. The most serious one is that the female figure was described as a “noble” (chinjok 眞族). There is no evidence that shamans were referred to as nobles in ancient Korea. In this regard, the second view purports that the woman was the wife or daughter of a local aristocrat who suffered from a disease. The nails were seen as a means to cure her disease (Kim Ch’angsŏk 2010). A traditional treatment known as ‘piercing and hurting therapy’ (chasangbŏp 刺傷法) continued to prevail until the early twentieth century in Korea. A face was drawn so that nails could be driven into the eyes in order to cure eye diseases. A body was drawn on the ground so that the head could be chopped off with a sickle in order to decrease the fever associated with malaria (Murayama Jijun 1929, 252–255). As such, the origins of these folk remedies may very well be traced back to the mokkanslips of Hwawang Fortress.19 In addition, the tale about the origin of the Ch’angnyŏng Cho clan has been handed down in the Chosŏn dynasty.

This story implies that the reservoir was a sacred place where a ritual related to a dragon and disease treatment was held. The woman on the mokkanmust have had such a serious illness that an effigy of her was carved on the mokkan. A ritual to expel the disease by driving six nails into such an effigy was in all likelihood held around the reservoir. Then the mokkanwas thrown into the den of the dragon. The dragon king was believed in ancient Korea to not only be a rainmaker, but also a being that had the power to cure diseases (Kim Ch’angsŏk 2010, 109–112).

However, the deciphering of the scripts on the mokkanhas proven difficult. There are not many examples of mokkanslips that were used for memorial services or ritual ceremonies. More detailed conclusions can be expected when other similar artifacts are discovered.

13A look at the Kwanggaet’o Stele (erected in 414) and Chungwŏn Koguryŏ Stele (erected in the mid-fifth century) shows that the kings of Paekche and Silla, which were regarded as being subordinate to Koguryŏ, were referred to as nogaek (奴客). 14The use of chi (支) as a noun ending referring to people is commonly found in the steles of Silla erected during the sixth century, such as the Naengsu Stele in Yŏngil, Pongp’yŏng Silla Stele in Ulchin, and the Silla Chŏksŏngbi Stele in Tanyang (Kwŏn Inhan 2008). It was used as part of the names of people whose status was higher status than that of kongmin (公民, commoner). 15According to such assertions, pu (負) did not indicate the transportation method of carrying things on one’s back. Rather, it indicated the units of freight or baggage. 16Geography Section of Samguk sagi (History of the Three Kingdoms) Vol. 36 Muju. “Kŭmsan-gun was originally known as Palla-kun under Paekche. It was renamed Kŭmsan-gun by King Kyŏngdŏk. It currently belongs to Naju-mok (mid-twelfth century). It controls three prefectures (hyŏn), one of which Hoejin-hyŏn was originally known as Tuhil-hyŏn until it was renamed by King Kyŏngdŏk…” 17It states that the man, Sadalsasa (巳達巳斯), who lived in the capital city of Paekche, was requisitioned to a rice paddy in a local province (Yi Sŏngsi 201 0, 106–107). He took several people with him. A hole was made in it so that it could be bound with other mokkan which had texts on laborers and their working place, as in the case of Pogam-ri mokkan No. 5. 18The photograph was taken after all the nails were removed for investigation. 19Taking a look at the Sanguozhi (三國志, History of the Three Kingdoms), the Wuhan tribe had a custom that involved extracting blood from a sick person by piercing the skin in the affected area. Thus, piercing and hurting therapy was an accepted ancient medical custom in Northeast Asia. 20Yŏji tosŏ (Cultural geography of Korea). Compiled in 1757–1765. Hwawang Fortress, Ch’ang-nyŏng, Kyŏngsang Province. A look at the genealogies of the Ch’angnyŏng Cho Clan reveals that this tale was mentioned in the family genealogy of Cho Wi and Cho Sik who lived during the early Chosŏn period. We can thus conclude that the tale of Yehyang and the reservoir of Hwawang Fortress was passed down from generation to generation within the Ch’angnyŏng Cho Clan as a progenitor tale.

There is no doubt that the writing system employed in ancient Korean polities came from ancient China. This writing system was introduced via the cultural interactions with Chinese kingdoms during the Old Chosŏn period and the commanderies established by the Han dynasty. However, certain differences exist between ancient Chinese wooden slips and Korean mokkan.

In terms of the species of trees employed, bamboo was not used generally as a writing material in ancient Korea. It would appear that the opportunity to use bamboo increased after the Koryŏ Dynasty, as evidenced by the Mado and Taean mokkanslips (Im Kyŏnghŭi and Ch’oe Yŏnsik 2010). These were placed in a ship that sunk while transporting goods from what is now Kangjin, Haenam, and Naju to the capital of Koryŏ Kaegyŏng (present-day Kaesŏng). Among the mokkan discovered in the Mado site were shipping tags made of bamboo.

Yet, these bamboo mokkan do not have any specific differences from the mokkan slips made of other tree species. It seems that the diffusion of the recording system and mokkan culture to the southern seaside districts of the Korean peninsula, where bamboo is ample, would have made this possible. However, even though some Mado mokkan slips were made of bamboo, these were used not for documents or scriptures but as shipping tags. Of course, they were also not bound to each other with straps like the bamboo slips of the Analects of Confucius unearthed at Chŏngbaek-dong in P’yŏngyang.

The mokkanslips on which the Analects of Confucius were inscribed that were excavated in Ponghwangdae and Kyeyang Fortress were also not made of bamboo. Their shape and size differ from those of the Han dynasty of China. They are estimated to be over 1 m in length and four or five sides featured letters rendered from top to bottom and right to left. This implies that in the seventh century at the latest, scriptures like the Analects of Confucius were written on paper after which it was bound as a book.

Long scripture mokkansuch as those uncovered from Kyeyang Fortress and Ponghwangdae were made for practical purposes such as studying Chinese characters in order to secure work as an official in local society or preparing for a kind of exam. The reason why there were bound mokkan in ancient Korea hitherto was that paper books only began to be used in the latter part of the Korean Three Kingdoms period.21 One scholar has speculated that the bound mokkan were replaced by multi-sided mokkan (Yun Sŏnt’ae 2007, 64–72). Whereas multi-sided mokkan developed from one- or two-sided mokkan because of their convenience of use, I believe the real substitute for bound mokkan was paper.

While they are not in the form of window blinds like the shape of the character ch’aek (冊) but a sheaf of basic data, Pogam-ri mokkan No. 2, 3, 5 and the Kungnamji mokkan may have been bound with other mokkanslips of the same kind. The presence of references based on the unit of working group or household would seem to indicate that officials would complete the final version of the family or tax collection register by putting them together. In addition, among the mudu (木牘, wooden slips), the plank type called pang (方), which is wider than mokkan, has not been found on the Korean peninsula, with the exception being a household statistics ledger from the Lelang Commandery.

Not only the obverse but also the reverse of Korean mokkanwere usually employed for transcription, and even multi-sided ones such as square or hexagon pillar shaped ones were made. Moreover, ancient Koreans sometimes wrote two or three lines on a slightly wider rectangular mokkan. These figures and characters share more similarities with Japanese mokkan than Chinese ones.22 In this regard, the differences between Korean mokkan and Chinese mudu derive from the above-mentioned indigenous tradition of communication using inscribed wood pieces. If people used only certain signs to communicate, as was the case in early sixth-century Silla, then there might not be a need to craft mokkan as wide as mudu. Moreover, differences would also have emerged as the Chinese mudu culture was adapted to ancient Korea. Of course, some new features must have been added in Japanese society as well.

Some scholars have advanced the idea that mokkanwere mainly used for tags in ancient Korea because they coexisted with paper documents. They assert that shipping tags for instance were made of wood lest they should tear or be damaged like paper. While mokkan may have been used for practical reasons not owing to the absence of paper but more to the advantages of wood (Hirakawa Minami 2000; Yun Sŏnt’ae 2007), certain documents on top of tags were nevertheless made using mokkan in Paekche and Silla. I presume that there must have been steps when it came to the completion of documents. For example, when one gave an oral report, it was then written on a mokkan, with the final version completed after all the related mokkan were collected and reviewed.

Moreover, there might have been a hierarchy among the means of official communication. While the top would have been edicts from the king, the next would have been a stele like the Chunsŏng-ri Stele in P’ohang followed by paper documents and mokkan. During the early stages of the adoption of the Chinese writing system, it would not have been enough to write down the order of the king. The best transfer method would have been to deliver it through oral means. However, reports from vassals or officials were performed orally via a mokkan. Following the diffusion of paper, the final version of documents began to be written on paper once the basic materials on the mokkan had been collected. In this regard, certain verdicts, judgments, and ordinances were inscribed on steles as proclamations. There is little doubt that all of these steps and methods functioned on the basis of oral communications with the people and between officials.

21Kim Kyŏngho, “Han’guk kodae mokkan e poinŭn myŏt kaji hyŏngt’ae chŏk t’ŭkching – Chungguk kodae mokkan kwa ŭi pigyo rŭl chungsim ŭro” (The physical characteristics of ancient Korean mokkan – with a special focus on the comparison with ancient Chinese mudu), Sarim Vol. 33 (2009). Kim has argued that bound mokkan were not used after the Three Kingdoms Period because the culture of Chinese characters was introduced to the Korean peninsula by the third–fourth century, by which point the mudu (wooden slips) were already being used for simple documents and tags in China. 22Watanabe Akihiro, “日本古代の都城木簡と羅州木簡” [Nihon kodai no tojou mokkan to naju mokkan, The capital mokkan of ancient Japan and Naju mokkan], 6-7 segi yŏngsan’gang yuyŏk kwa paekche [The Yŏngsan River Basin and Paekche] (Naju Cultural Properties Research Institute, 2010), 228–232.

So far, only 700 ancient Korean mokkan, including scobs, have been uncovered. This is a very small quantity compared to China and Japan, where hundreds of thousands of such items have been uncovered. However, as the excavation of mokkanin Korea continues, their numbers will inevitably increase. The prospect of research on mokkan is in this regard very bright.

Ancient Koreans wrote or engraved letters, signs, or drawings on mokkanto express their ideas and communicate with one another. Therefore, while records such as the Samguk sagi (History of the Three Kingdoms) and Samguk yusa (Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms) were published after the fact, the mokkan were contemporary records of the time compiled when the events actually emerged. And as mokkan slips were not compilations such as the histories mentioned above that were edited, they constitute a primary material.

Furthermore, the mokkando not contain exaggerations or ornamentation designed to show off achievements like the Kwanggaet’o Stele. The mokkan were made simply for practical purposes. Therefore, mokkan have such a high value as a historical material essential for research on the ancient history of Korea. Moreover, it is expected that these records will contribute to the study on the daily life of ancient Koreans by making up for the deficiency of historical records on that subject.

However, there are some limits, as well. The amount of text on mokkanslips is so small that the information which can be gleaned is fragmentary at best. Generalizations based solely on a few mokkan should be avoided. Rather, the text should be reviewed with the help of research based on historical records and epigraphs. Moreover, we should pay attention to mokkan as an artifact as well.23 Archaeological access and analysis of the remains and accompanying relics with the mokkan are crucial to understanding their contents and usage.

What’s more, as most Korean mokkanare hard to decipher, perhaps owing to the acidity of Korean soil, we need to try to read and copy the characters immediately after excavation. An interdisciplinary approach that includes archeology, paleography, humanities, and history is required because the mokkan materials have complicated attributes.

Lastly, a perspective that embraces all of East Asia is necessary. Despite their common origin, the wooden slips of Korea, Japan, and China have certain differences. In particular, the substantial differences between Chinese and Japanese wooden slips have led some scholars to conclude that these differences can be traced back to the invention of ancient Japanese wooden slip culture. But as the study on Korean mokkanadvances, it is becoming more evident that the writing system of mokkan was transferred to the Japanese archipelago after ancient Koreans had adapted the Chinese system to their own customs. As such, a comparison of mutual influences should be undertaken in the study of mokkan culture, with the scope extended to Southeast Asian nations such as Vietnam and even Inner Asia.24

23Japanese historians pointed out the characteristics of mokkan materials at an early stage. Unlike paper documents that have been preserved and inherited, the majority of mokkan materials are unearthed from the ground. To use these mokkan slips as historical materials, we need to first analyze the state of excavation (Kishi Toshio, “創刊の辭” [Soukan noji, On the publication of the First Issue], 木簡硏究 [mokkan kenkyu, Journal of mokkan Studies] First issue (Kyoto, 1979) 24Thirty mudu (wooden slips) of the Tang dynasty were discovered in Khotan Field in Xinjing Province, China in 2005. Chinese characters and Khotanese were written on these wooden slips. They were classified as shipping tags used to accompany freight (Rong Xinjiang and Wen Xin, “Newly Discovered Chinese-Khotanese Bilingual Tallies,” Journal of Inner Asian Art and Archaeology, Vol. 3 (2008)) There is a need to conduct a comparative analysis of these wooden slips as they were used for similar purposes as the mokkan slips at Sŏngsan Fortress in Haman.

![Mokkan No. 5 (left) and No. 35 (right) excavated in S?ngsan Fortress in Haman (Kaya National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, Han’guk ?i kodae mokkan [Ancient mokkan of Korea], 2004.)](http://oak.go.kr/repository/journal/17812/NRF003_2014_v17n1_193_f002.jpg)

![Mokkan No. 2 discovered in Pogam-ri, Naju. (Naju Cultural Properties Research Institute, Naju pogam-ri yuj?k I ? 1?3 ch’a palgul chosa pogos? [Naju Pogam-ri relics I: Report on rounds 1?3 of the excavation], 2010)](http://oak.go.kr/repository/journal/17812/NRF003_2014_v17n1_193_f003.jpg)