I. P’AN’GYO DISTRICT’S ZONE 10 BUILDING SITE, AND THE EXCAVATION OF BUDDHIST SCULPTURES

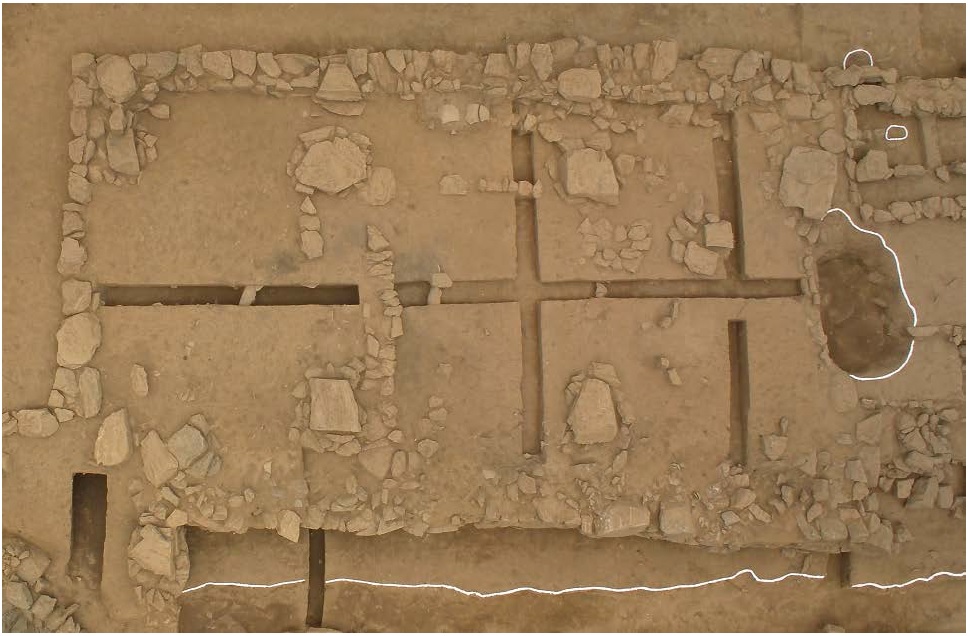

The three sculptures excavated from P’an’gyo in Sŏngnam City in 2008 are rare examples dating from the early Koryŏ period.1 These sculptures were excavated from the housing development site of P’an’gyo District in Sŏngnam City. Administratively, the area belongs to Pundang District, Sŏngnam City, Kyŏnggi Province, and is spread across three towns: P’an’gyo-dong, Hasanun-dong, and Samp’yŏng-dong. This area was investigated as part of a housing site development project that was motivated by a balanced area-development strategy. The cultural heritage investigation in P’an’gyo District started in 2001 with a ground survey being conducted by the Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation.2 The “C” area of Zone 10 where the Koryŏ Buddhist sculptures were found subsequently went through a trial excavation in 2005, and a full excavation in 2007–2008.3 As a result of these excavations, in Area C of Zone 10, the site of a south-facing building and facilities was found, along with a stone coffin tomb and nine wooden coffin tombs. The associated relics excavated from the site indicate that the building was established around the end of the Koryŏ period or the beginning of the Chosŏn period. A gilt-bronze Vairocana Buddha statue, two gilt-bronze Bodhisattva-like images, and a gilt-bronze small stupā were found together, making it possible to assume that the building was used as a small hermitage (temple) (Plate 1).4

This article examines the period of manufacture of the gilt-bronze Buddha and Bodhisattva-like images excavated from Area C of Zone 10 in P’an’gyo District, as well as their characteristics and significance. As there are very few examples of early Koryŏ Buddhist statues for which the period of manufacture can be identified with the aid of written evidence or inscriptions, the sculptures of P’an’gyo are of great significance as early Koryŏ works. Analyzing the excavated material and the site in tandem could contribute to restoring the past culture and religion of the P’an’gyo area, and to a widening of the horizons of Koryŏ cultural studies.

The building site from which the Buddhist sculptures were recovered is in Zone 10 of the P’an’gyo housing site development area. Zone 10 is located at the end of the eastern mountain range of Mt. Kŭmt’o, which is to the east of the Sŏ-P’an’gyo area. From the ground survey conducted in 2001, the site of a building thought to date from the late Koryŏ to early Chosŏn period was confirmed. In consideration of the terrain, Zone 10 was divided into three parts, for excavation purposes. From the northwestern slope came Area A and B, and the eastern slope of the range became Area C. From Area A, eighteen wooden coffin tombs were recovered and two pits unearthed, whilst from Area B one stone coffin tomb and four wooden coffin tombs were recovered. From Area C, the discovery of a building and facilities, together with one stone coffin tomb and nine wooden coffin tombs, was confirmed.5

Area C consists of two hills. The south-facing building site and its affiliated facilities were revealed from the western hill of Area C, which is on the northeastern side of Zone 10. From this building site, a large number of roof tiles and pottery pieces were excavated, and all date from the late Koryŏ to early Chosŏn period. Additionally, white porcelain from the Chosŏn period was excavated. The affiliated facilities site—featuring a floor-heating system—is adjacent to the east of the building site, and to the south of the affiliated facilities, a site where a stone lantern was supposedly located has been confirmed. Further south, a stone drainage system was found. The north of the building site is encircled by an outer wall, and between the building site and the wall, a stone terrace was found. The building site of Area C is small in size, and because not many buildings had been constructed during that period, it is highly likely that the site is of a hermitage rather than a large-scale temple.

The statues, small gilt-bronze stupā, and stone stupā were excavated from within and around the building site. From the central northern wall of the building site—where the discovery of foundation stones has been confirmed—the two Bodhisattva-like sculptures, celadon dishes, shards of earthenware pottery, and a great number of roof-tile fragments were unearthed. Roof-tile pieces were piled up in front of the southern foundation, from which the upper part of the small gilt-bronze stupā and one Vairocana Buddha were recovered. Three other pieces—presumably belonging to the top of a stone stupā—and one piece of a stone lantern were found as well, and numerous roof tiles were found in places where the building site’s surrounding walls once were. From the south of the adjacent affiliated facilities building, a furnace was found equipped with floor-heating systems; this finding indicates that the building had been used for residential purposes. Broken pieces of celadon, a celadon cup, roof tiles, and iron objects of unidentified use were also found there. The outer walls situated in the middle of the eastern slope of the excavation area encircle the building site to the south. A celadon cup, a white porcelain bowl, a small number of earthenware pottery shards, iron fragments, and numerous roof-tile fragments were found in the surrounding areas.

One point 160 cm southwest of the building site is thought to have been the site of a stone lantern. The floor is square-shaped and was filled with small and large stones to maintain a flat, level area; presumably, a stone lantern was erected on top. Roof tiles outnumber all other excavated artifacts from the building site of Area C in Zone 10 of P’an’gyo District. Various other artifacts—such as earthenware pottery shards, celadon and white porcelain shards, gilt-bronze artifacts such as the Buddha statue and the two statues that are the focus of this article, a stone stupā, stone lantern parts, and iron parts—were also excavated. Roof tiles were concentrated in many areas of the sites, and most have the stylistic characteristics of late Koryŏ–early Chosŏn roof tiles. This finding suggests the possibility of the building having stood until the early days of the Chosŏn period. The variety of excavated artifacts indicates that the Koryŏ period building had been demolished at the end of the Koryŏ dynasty, but that it was reconstructed during the Chosŏn period, when white porcelain was in use.

1“Early Koryŏ” refers to the period used as a standard in Korean art history that divides the history of Koryŏ into two periods. The division lies in 1270, the time when the Mongol invasion and occupation of Koryŏ took full force. Therefore, the period starting from the establishment of Koryŏ (918) to 1270 is considered “early Koryŏ,” whilst 1270–1392 is referred to as “late Koryŏ.” 2See Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation ed., Sŏngnam P’an’gyo chigu t’aekchi kaebal saŏp yejŏng puji munhwa yujŏk chip’yo chosa pogosŏ [Report on the Cultural Heritage Ground Survey of the proposed site for housing development in P’an’gyo District of Sŏngnam] (Sŏngnam: Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation, 2002). 3Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation ed., Sŏngnam P’an’gyo chigu munhwa yujŏk 2 ch’a palgul chosa- 8 ch’a chido wiwŏn hoeŭi charyo [Information for the 8th Advisory Meeting – 2nd Excavation for the Cultural Heritage of P’an’gyo District] (Sŏngnam: Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation, 2008a); Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation ed., Sŏngnam P’an’gyo-dong yujŏk II - Sŏngnam P’an’gyo chigu munhwa yujŏk 2 ch’a sibalgul chosa pogosŏ [Report of the 2nd Trial and Main Excavation for the Cultural Heritage of P’an’gyo District, Sǒngnam II] (Sŏngnam: Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation, 2008b). The reporter designated the areas by the han’gŭl terms “Ka”, “Na”, and “Ta”. Here for the convenience of the readers, I have changes them to “A”, “B”, and “C”. 4Yun Seonyoung (Yun Sŏn-yŏng), “Sŏngnam P’an’gyo chigu munhwa yujŏk palgul ŭi sŏngkwa,” [The outcome of the cultural heritage excavation in P’an’gyo District, Sŏngnam City], Che 13 hoe haksul hoeŭi palp’yo nonmun chip – P’an’gyo t’och’on chigu palgul munhwajae ŭi pojŏn pang’an [13th academic symposium presentation papers – The conservation plan for the excavated cultural heritage of P’an’gyo and T’och’on Districts] (Sŏngnam: Local Culture Research Institute, Sŏngnam Cultural Center, 2008). 5Detailed information on the building site and the related excavated sites in Area C in Zone 10 can be found in the excavation report of the Sŏngnam P’an’gyo District. Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation ed., Sŏngnam P’an’gyo-dong yujŏk II - Sŏngnam P’an’gyo chigu munhwa yujŏk 2 ch’a sibalgul chosa pogosŏ.

II. ICONOGRAPHY AND DATING OF THE BRONZE BUDDHIST STATUES

1. Iconography of the Two Monk Figure Statues: Arhat, Sengqie, or K?itigarbha?

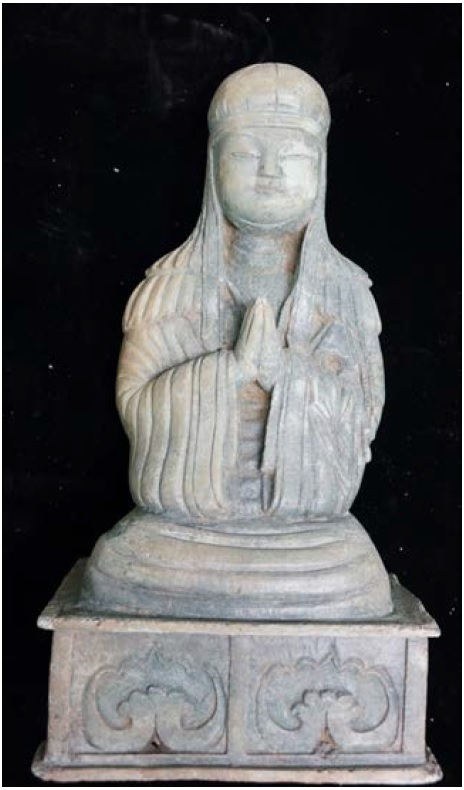

The three Buddhist statues excavated from the Zone 10 of P’an’gyo are in excellent condition; their original forms have been fully preserved (Plate 2). The thickness of the bronze is even and the surfaces are smooth, without any air bubbles. The casting is of a high standard, showing the skill used to manufacture these high-quality goods. This section of this article focuses on what these three statues were made to be and worshipped as, as well as their date of manufacture. The current trend in art history studies is to examine the socio-religious sig-nificance and the worship context, as well as the iconography and form of such works of art. However, due to the limited nature of background information on Koryŏ sculptures, priority must be placed on studying the actual object itself.

The smallest statue of the three is of a figure whose hands are in the

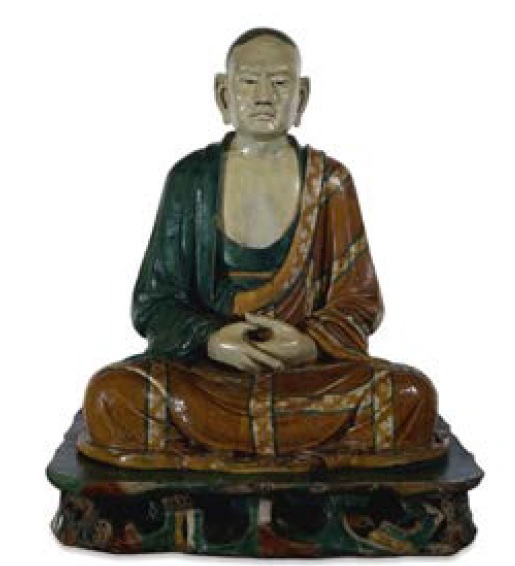

Figures with hands held in prayer are usually thought to signify monks or arhats; therefore, this article will explore the possibility of these statues being arhats. Both are wearing monk’s robes and hoods on their heads, and both are holding the palms of their hands together in prayer. The arhats from the Five Dynasties period (907–960), Song period (960–1279), or late Koryŏ–early Chosŏn period were established as a group typically comprising 16, 25, or 500 arhats.6 Although the arhats may have constituted a “set,” this does not imply that they all have the same appearance; additionally, cases where entire sets have been kept together are very rare. These arhats are generally depicted as monks, with each one bearing strong individual characteristics. This can be seen in the arhats of the Lingyansi Temple in Mt. Wutai, Shanxi Province, or the Liao three-color (

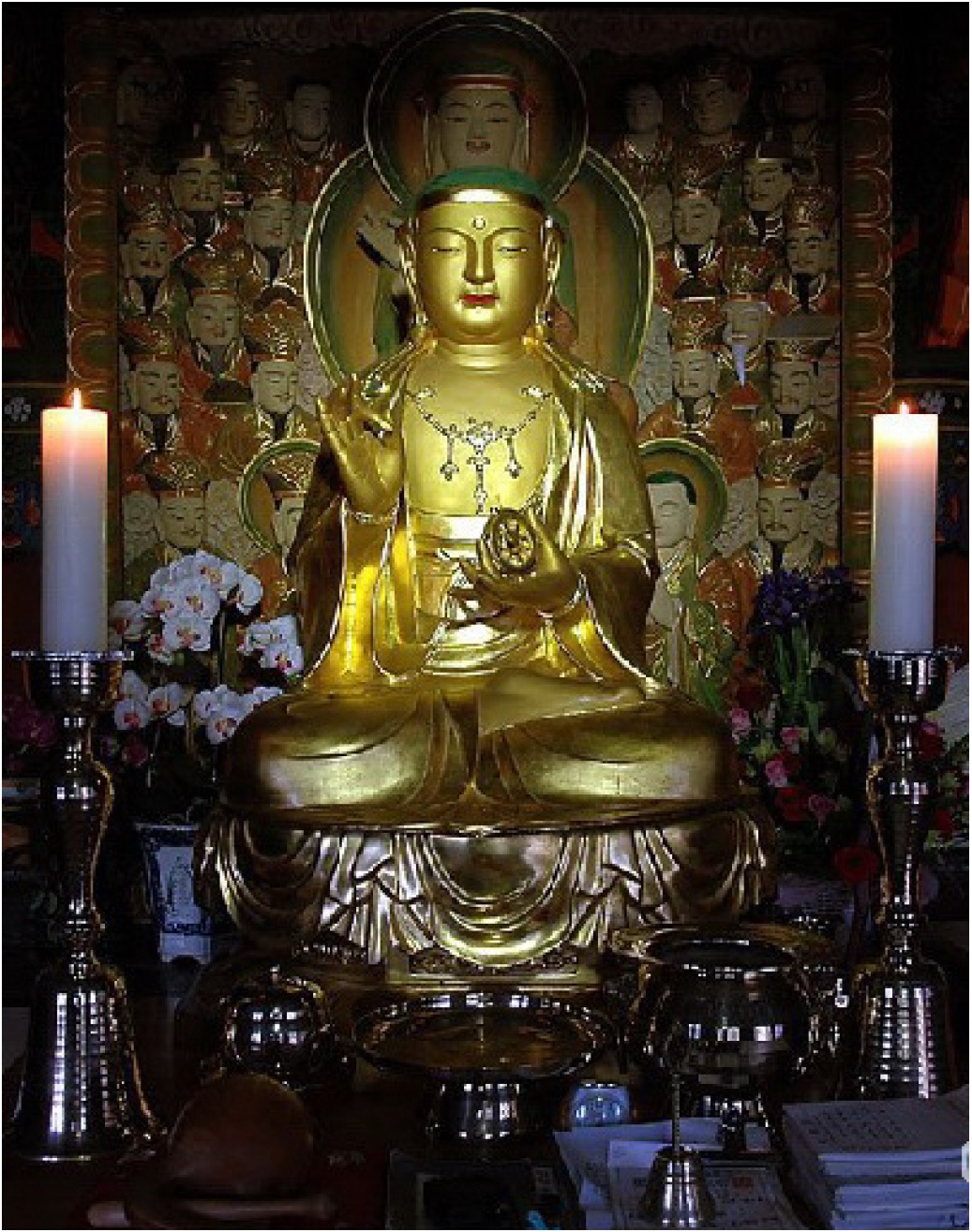

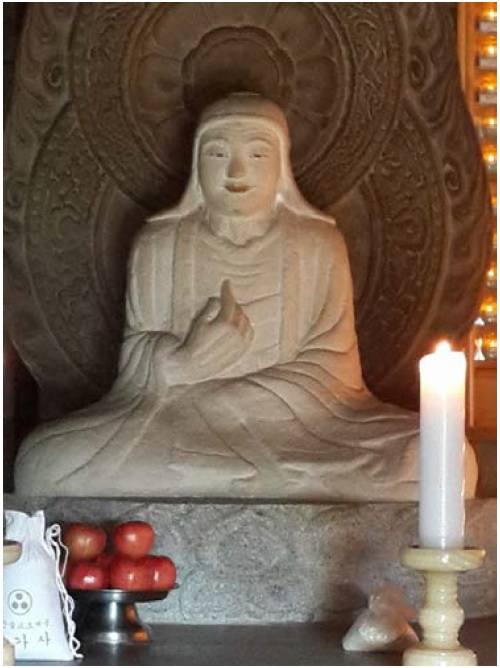

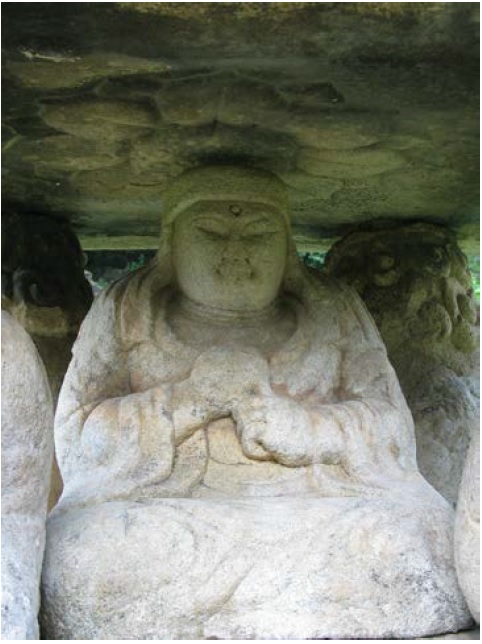

Next, let us explore the possibility that the statues are images of Kṣitigarbha.8 As they are both wearing hoods, these statues can easily be thought to be the Bodhisattva Kṣitigarbha: that is because the Korean name “P’imo Chijang (被帽地藏) posal,” referring to Kṣitigarbha, originates from the image of the late-Koryŏ Bodhisattva who wears a hood on his head. Hooded Buddhist statues were mostly made during the period between the late Koryŏ and early Chosŏn in Korea, and most of these are known to be of the Bodhisattva Kṣitigarbha.9 The Bodhisattva Kṣitigarbha of this period, in the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries, is depicted as a monk with a shaved-head or as a Bodhisattva who wears a hood and holds a staff and a cintāmaṇi. This can also be seen in the Koryŏ Buddhist paintings from the fourteenth century and the early gilt-bronze statues of the Chosŏn period. The “Painting of Kṣitigarbha by No Yŏng,” drawn in 1307, depicts Kṣitigarbha as a monk with a shaved-head lacking any decoration, and holding a cintāmaṇi. This proves that the iconography shown in the Kṣitigarbha image in Sŏkkuram Grotto has been long kept as a tradition. The “Painting of Kṣitigarbha by No Yŏng” is an important and definitively dated piece that can serve as a standard in identifying Buddhist art. The fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Kṣitigarbha shown in the Koryŏ painting is either portrayed as a magnificently decorated Bodhisattva or a monk wearing robes. However, when he is depicted as a monk, he does not wear a hood; this also applies to all the statues. The Kṣitigarbha statue in Sŏnun Temple of Koch’ang—a representative work of the late Koryŏ period—and the Amitābha triad with the Avalokiteśvara and Kṣitigarbha recovered from Mt. Kŭmgang and housed at the P’yŏngyang History Museum in North Korea also attest to the iconography (Plate 5).

Are the two statues excavated from P’an’gyo in fact Kṣitigarbha statues? These figures are wearing hoods similar to the depiction seen in the “Painting of Kṣitigarbha” and in the Kṣitigarbha statues from the late Koryŏ period, but they hold neither a staff nor a cintāmaṇi. They are, however, holding their hands together in prayer, and this differentiates them from the regular Kṣitigarbha images of that time. It is also difficult to say whether these two statues followed the example of the Kṣitigarbha images of the Unified Silla period, compared to the Kṣitigarbha images that hold a cintāmaṇi. These statues also lack decorations, compared to the Kṣitigarbha statues made during the late Koryŏ to the early Chosŏn period, which were adorned luxuriously with beaded necklaces. It is therefore difficult to argue that these statues are depictions of Kṣitigarbha, as they differ distinctly from other examples from the same period.

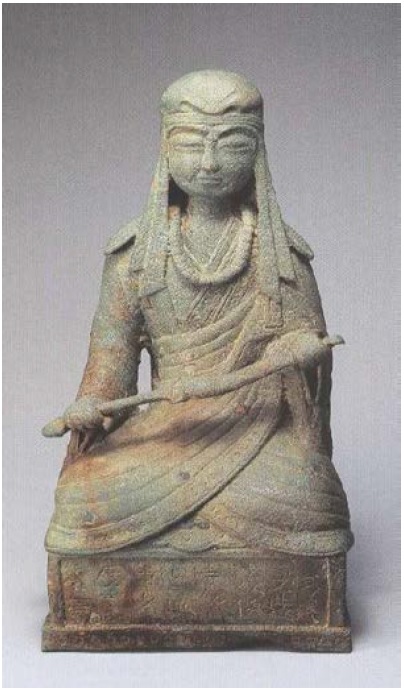

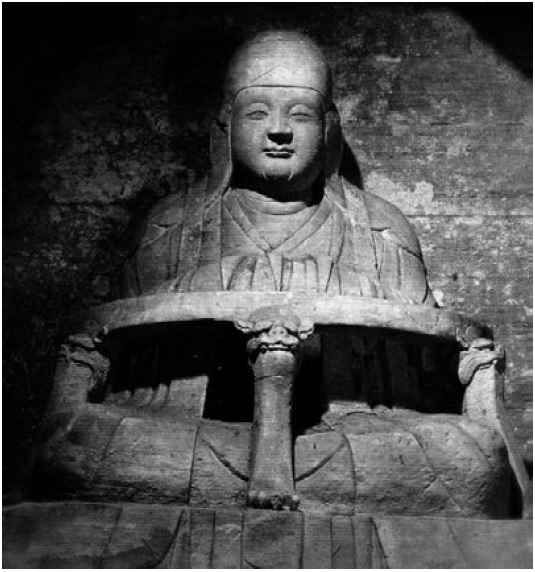

Another option, which is similar to the images of arhat or Kṣitigarbha, is that the image is of the Great Monk Sengqie (pronounced Sŭngga in Korean).10 The Great Monk Sengqie (628–710) was revered as one of the Three Saints during the Tang dynasty, together with the Monks Baozhi and Wanhui.11 Sengqie was originally from Kusnak, north of the Pamirs. He went to Tang China when he was thirty years old and was active in China for fifty-two years. In 661, he established Puzhaowang Temple in Sizhou and enshrined the Puzhaowang Buddha as the main Buddha. Even when he was alive, he was revered as the living embodiment of Avalokiteśvara; following his death, he was called “the Great Saint of Sizhou” (modern Liuhuai, Anhui Province, 泗州大聖) and venerated as an incarnation of Guanyin (Avalokiteśvara). Shrines in his name were established all over China, as he was renowned for protecting people from floods, droughts, and thieves, just as Avalokiteśvara was. The cult of Sengqie is mentioned in the literary works of Ch’oe Ch’i-wŏn, indicating that it had spread to Silla by the end of the Silla Kingdom. Like the statue of Sengqie that stands in Sŭngga Temple on Mt. Pukhan in Seoul, images of Sengqie wearing robes with a hood on his head were found; they hold nothing in their hands (Plate 6). The cult of Sengqie is mentioned in many literary collections and in the

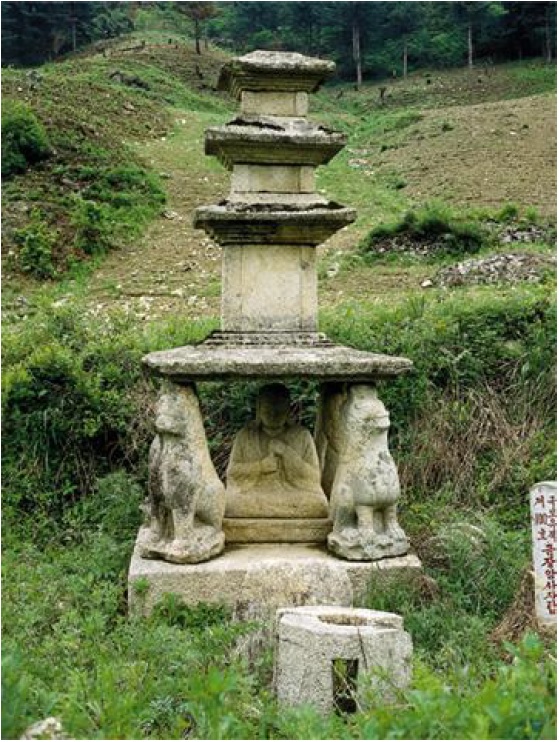

The human figure in the middle of the stone stupā in Sajabinsin Temple in Chech’ŏn, North Ch’ungch’ŏng Province is presumed to be the figure of Sengqie.13 This figure is very similar to the Sengqie images of China, except that the hands are held in the

The Sengqie images of China are confirmed as such by inscriptions with the name “Sengqie”; they also wear monk’s robes with hoods on their heads and hold their hands in the

Before determining the iconography of the two statues excavated from the building site in P’an’gyo’s Zone 10, it is helpful to review their relationship to the Vairocana Buddha. As one Buddha statue and two statues with hoods were excavated at the same site, it can be inferred that the three were created as a triad; nonetheless, their stylistic differences make it highly improbable that the three statues were manufactured within the same period. It is also not customary to make the supportive Bodhisattvas larger than the main Buddha; therefore, it cannot be presumed that the three were made as a set from the outset. However, judging from their styles, their dates of manufacture do not seem to be overly divergent, and it appears that the three were likely made in the same workshop. The three statues were found at the same building site because they were probably enshrined in the building for different reasons. There is also the possibility of the two twin-like statues being placed at the sides of a yet-to-be-found Buddha. A case where two Bodhisattvas look exactly alike can be found in the example of the Vairocana Buddha triad at Yŏngt’ap Temple in Tangjin. Like the triad in Yŏngt’ap Temple, the two statues at P’an’gyo could have been made as the supporting figures of a triad, or they could have been made as independent objects of worship.

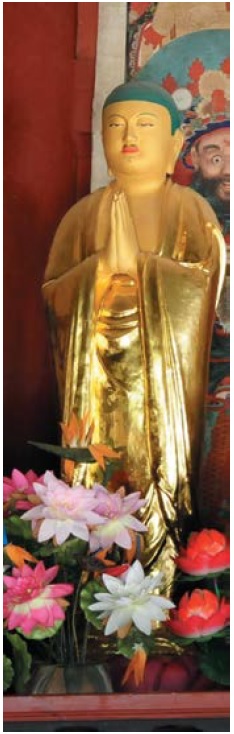

In East Asia, Kṣitigarbha tends to hold a cintāmaṇi; he may not have a staff, but he has a cintāmaṇi. However, the standing Kṣitigarbha statue at Sinan Temple in Kŭmsan holds neither a staff nor a cintāmaṇi; he merely holds his hands together in prayer (Plate 9). This monk-style standing Bodhisattva Kṣitigarbha has the function of supporting the Amitābha Buddha, with Avalokiteśvara on the other side.18 These appear to be works of the early fourteenth century, near the end of the Koryŏ period. They also have marked resemblances, compared to the Vairocana Buddha statues made in the thirteenth century. The Kṣitigarbha statue of Sinan Temple is different from the P’an’gyo images, in that it has a bald head; however, they are similar in that they both have an undecorated appearance. It is important to note that the number of decorations on Kṣitigarbha images in-creased towards the end of the Koryŏ period, in line with the stronger influence of Yuan dynasty art.19

The two statues excavated from P’an’gyo appear to have originally been created as Sengqie images that went on to be worshipped as images of Kṣitigarbha. At the beginning, the view of Sengqie as a protector in the Sengqie faith would have constituted an important factor.20 Although not to the same degree as Sizhou (where Sengqie was active) or Ch’ungju (where Sajabinsin Temple is located), P’an’gyo was also a major transportation location where land and sea routes converged.21 P’an’gyo, which currently serves as an interchange for Kyŏngbu Expressway, was a place where a land route had developed since early times: people had to pass through the region in order to reach the southern route that came down from Kaesŏng via Seoul. The T’anch’ŏn stream, a tributary of the Han River, was also used as a watercourse, contributing to the development of P’an’gyo as a transportation hub (Plate 10). This area that belonged to the local administrative unit of Kwangju Prefecture had a horse-changing station for government officials (

No statues in Korea have been confirmed by any text to be in the image of Sengqie; nonetheless, Sengqie belief—which developed in the center of the Jiangnan region of China—was most probably transmitted to Koryŏ from Song China by travelers such as merchants, monks, and government officials. That belief is thought to have been introduced by these people, and it is believed that images of Sengqie were constructed so that they could pray for safe travel. As has been pointed out several times previously, the cult of Sengqie developed due to the fact that it formed a relationship with the royal family in the early Koryŏ period. As can be found in Yi Ye’s “Records of Establishing Sengqie Cave in Mt. Samgak,” the Koryŏ royalty “conducted three-day rituals in spring and autumn, and offered the King’s clothes.” This entry indicates the spiritual power of Sengqie Cave in Mt. Samgak and the faith that the Koryŏ royalty placed in it. Although the text refers to Sŭngga Temple, the scope of its contents cannot be limited solely to Sengqie Cave in Mt. Samgak.23 Images of Sengqie were pre-sumably established nationwide in order to “receive an answer to prayers concerning any questionable incidents happening within the state.”24 This kind of belief closely resembles the cult of Sengqie during the Northern Song period (960–1127); it also relates to the Koryŏ envoys conducting rituals in the Puzhaowang Temple in Sizhou.25 The current findings in excavations—which reveal more and more cases of Song currency being found all over the country—attest to the fact that Song China had a great influence on Koryŏ. In the

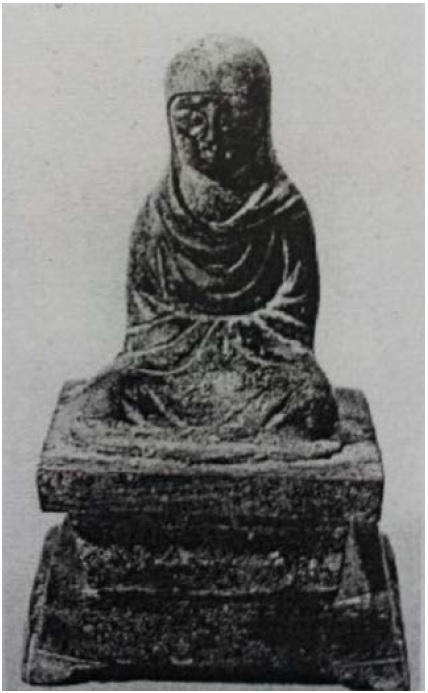

The bronze Vairocana Buddha from P’an’gyo has a slender face and a pointed

Nonetheless, the statues excavated from P’an’gyo differ from these; the details of the robes, in particular, show a striking difference. However, it is interesting that the two statues and the Vairocana Buddha share these details. These statues do not share any stylistic similarities with the statues of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries; rather, they have a similar base to the image of the Piṇḍola-Bhāradvāja statue housed in the Chŏnju National Museum.28 In fact, the expression of the body, the way in which the robe is worn, and the ends of the clothes hanging in a “U” shape between the two legs are reminiscent of one of the statues from Northern Song. These characteristics are especially similar to those on the Sengqie images found in Suzhou and Shanghai, rather than on those found in the Dazu caves on Beishan in Sichuan or Xiajiang, which are known to date from the late eleventh century to the early twelfth century. The Sengqie image found in the stone stupā in Ruiguang Temple in Suzhou is thought to have been produced between 1013 and 1017; in that image, Sengqie is wearing a hood and monk’s robes, and the robes fall down to his legs in a “U” shape, similar to what is seen on the P’an’gyo statues. The same can be said for the Sengqie image from the stupā at Xingjiao Temple in Shanghai, which is known to have been made between the years 1068 and 1093 (Plate 13). The only difference is that whereas in the image from Ruiguang Temple Sengqie is meditating with his two hands held together, in the image at Xingjiao Temple he has both hands hidden under his robes.29

The Sŭngga images found in P’an’gyo, however, are wearing much more complicated and intricate hoods (Plate 14). The long strings that tie the hoods together are draped by the ears; the rest of the hood is double-folded and covers the shoulders, showing the elaborate handiwork employed. The hood shape is different from the hood of the Piṇḍola-Bhāradvāja statue in the Chŏnju National Museum or the Kṣitigarbha image from the stone stupā in Maegok-dong in Sunch’ŏn City. The image most closely resembling this one is the Kṣitigarbha statue in Sŏnun Temple; these two share the similarity of the rounded robe ends between the knees, although the lengths differ. The decorative hood can also be seen in the Buddhist paintings of Koryŏ. However, in fourteenth-century Koryŏ Buddhist paintings, the hood of Kṣitigarbha has short string ties near the uncovered ears, and the hood is draped in a much longer fashion over the shoulders. The method of wearing the robe and the bead necklace decoration are also points on which the Sŏnun Kṣitigarbha and the “Painting of Kṣitigarbha” differ from the P’an’gyo statues.

It is not easy to date the three sculptures excavated from P’an’gyo, given that they display such different techniques from other known Koryŏ sculptures. All three exhibit very unique characteristics compared to other existing Koryŏ sculptures, and this makes it difficult to analyze their iconography and forms. There are not so many images dating to the twelfth century to compare them with. Besides these sculptures from P’an’gyo are definitely different from other Buddhist images in the late Koryŏ period. The stylistic features of the sculptures from P’an’gyo cannot be easily classified into any existing group of Koryŏ sculptures. These sculptures do not share visual similarities with statues from the tenth to eleventh centuries, not to mention the group of sculptures from the fourteenth century.

An example that the statues resemble most is the Buddha triad of Pyŏngnyŏn Hermitage (壁蓮庵) attached to Naejang Temple, of which only a photograph exists (Plate 15). They share similar facial outlines and bodily proportions, but the hood and robes are executed differently. Although it is difficult to compare the form of the P’an’gyo statues to extant images in Korea, it is easier to compare them to Buddhist sculptures from the Jiangnan region of China, which were produced in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. As these statues show similarities to those sculptures and differences from the fourteenth century Buddhist paintings of Koryŏ, the period of manufacture can be considered to be the early twelfth century.

Chinese coins excavated from the site serve as strong supporting evidence of this theory, as most of this Chinese money is from after the eleventh century. A total of forty-seven pieces of Chinese currency were excavated from four wooden coffin tombs from Area A of P’an’gyo’s Zone 12. The earliest from the collection is the “Zhidao yuanbao” (至道元寶), which was in circulation between 995 and 997; the latest is the “Chongning zhongbao” (崇寧重寶), which was in circulation between 1102 and 1106.30 Of these, sixteen Chongning zhongbao coins were excavated, comprising the largest group of a single currency type. Although Zone 12 and Zone 10 are at a distance from each other, given the total amount of coins excavated, it is feasible to think that P’an’gyo was an important regional locale during the eleventh and twelfth centuries. The statues excavated are thought to have been produced in the early twelfth century, when the cult of Sengqie was still prevalent within Koryŏ.31

The historical development of P’an’gyo was interrupted after the Mongol invasion in 1231. During the first invasion of the Mongols, the residents of Kwangju—including those of P’an’gyo—became exempt from corvée labor when they successfully fought off the Mongol army in the battle of Kwangju Mountain Fortress in 1232, under the leadership of Yi Se-hwa (李世華, ?–1238). The defeated Mongol army subsequently marched to Ch’ŏin Fortress (處仁城) in Yongin under the command of General Sartai, who was eventually killed by the monk general Kim Yun-hu (金允侯).32 There are records testifying that all the residents in the area were killed during the fierce battles against the Mongols in these areas, and this makes it likely that the area experienced an interruption in its historical development.33 The roof tiles excavated from the building site in Zone 10 of P’an’gyo, which were made across several different periods, attest to this fact. These tiles were manufactured separately and do not show evidence of gradual change. With a complete severance from the past due to the Mongol invasions, the reconstructed local area would have witnessed a rise in the cult of Kṣitigarbha, in order to console the spirits of the dead, thus answering the need to conduct rituals for the souls sacrificed during the war. The cult of Kṣitigarbha persisted until the early Chosŏn period together with the Kṣitigarbha images enshrined in stupās together with those of Amitābha and Avalokiteśvara.34 Rescuing the ancestors’ spirits from hell by creating Kṣitigarbha was an acceptable and respected act—even in the Confucian state of Chosŏn, which emphasized filial piety.35 It is important to note that until the early Koryŏ period, the objective of the cult of Kṣitigarbha centered on the elimination of one’s own sins, but this gradually shifted into guiding lost souls and providing healing.36

With regard to reconstructing the region, there are a few records worth noting. One record provides an account of a man called Cho Un-hŭl (趙云仡, 1332–1404) rebuilding the official government inn at P’an’gyo and becoming its director; other records testify to the P’an’gyo wŏn aiding those people who had travelled from the south in order to build the fortress in Hanyang (present-day Seoul), following the establishment of Chosŏn.37 In the early fourteenth century, Kwangju Prefecture, the administrative unit to which P’an’gyo belonged, was downgraded to a

During the second excavation of the P’an’gyo area, approximately 740 tomb sites were found dating from the Koryŏ and Chosŏn periods; most of them were commoners’ tombs from the Chosŏn period. This indicates that after the fourteenth century, this area functioned as a regional graveyard.39 After the Mongol invasions ended, people seemed to gather to build a new village near the River T’an’chŏn area from the ruins of war. Since there are few records about Sengqie in those periods, unlike in earlier times, we can reason that they did not know the original purpose and meaning of belief in Sengqie anymore. When they found the images from the devastated area, people in P’an’gyo might have thought the sculpture was a hooded Kṣtitigarbha which would have been familiar to them. It seems that they wanted to have their own Kṣtitigarbha for prayer to express their condolences for the deceased during the war against the Mongols. A number of wooden coffin tombs from the Koryŏ period have been excavated; among the many articles found including ceramics and bronze spoons, there is a possibility that evidence of the cult of Kṣitigarbha continuing from the Koryŏ–Chosŏn periods can also be found.40 Furthermore there are no other residential buildings excavated around the small building site where these sculptures were discovered. This means that the isolated hermitage provided a ritual space for the salvation of the souls of the deceased from falling into hell. It is plausible that the village people who had restored the town needed a place to hold a ritual for the dead apart from their own homes. Koreans prefer to divide the spaces for the living and the dead. The location of hermitage building site, which is far away from the village in Naksaeng or P’an’gyo, suggests that the area belonged to the dead. It is probable that the Bodhisattva-like images were worshipped as Kṣtitigarbha after the restoration of the town. The distribution of tombs in the P’an’gyo area—in close proximity to the building site where the three sculptures were found—indicate that although the building site in Zone 10 is only a small temple, it must have been the center of the worship of Kṣitigarbha within the region, with respect to guiding the spirits of the dead. Actually the cult of Kṣitigarbha never ceased nor was discarded after its transmission in the late Silla period. Even after Chosŏn was established, the cult of Kṣitigarbha still flourished. Not only Buddhist paintings featuring Kṣitigarbha from the Koryŏ period but also many Bodhisattva Kṣitigarbha sculptures dating to the sixteenth century still remain in Korea. However, there are a few Bodhisattva Kṣitigarbha sculptures dating from the early Koryŏ period before the Mongol invasions known to the public along with inscriptions or objects put into the belly of Buddha statues.

Even if the cult of Kṣitigarbha was first introduced in the eighth century, the image of Kṣitigarbha is hardly found before the late Koryŏ period. This causes difficulty for scholars trying to investigate the cult of Kṣitigarbha in the Koryŏ period. This is the reason why we cannot be certain that the statues discovered from the P’an’gyo District were originally created as images of Bodhisattva Kṣitigarbha.

6The 16 arhats are mentioned in Fazhuji (法住記, Records on the duration of the Law) by Xuanzang. The texts that mention the 25 arhats and 500 arhats are Anguttara Nikaya (增一阿含經, Gradual collection), Shisonglu (十誦律, Ten chanting law), and Fahuajing (法華經, The Lotus Sutra). 7Choe Song-eun (Ch’oe Sŏng-ŭn), “Koryŏ sidae Pulgyo chogak ŭi tae-Song kwan’gye,” [Relations between Buddhist sculpture of Koryŏ and Song China], Misulsahak yŏn’gu [Korean Journal of Art History] Vol. 237 (2003), 49–73. Based on the inscription of Yŏngt’ong Temple, there is a tendency to consider the upper limit of the establishment of the arhats as 1027, the 18th year of King Hyŏnjong’s reign and the year in which the temple was established. However, it cannot be proven that the temple and the arhats were established in the same year. 8Studies conducted on the Korean Kṣitigarbha images are cited in the following papers: Park Young-sook (Pak Yŏng-suk), “Kṣitigarbha as Supreme Lord of the Underworld,” Oriental Art, vol. 23 (1977); Kim Junghee (Kim Chŏng-hŭi), “Koryŏ mal Chosŏn chŏn’gi Chijangposal-hwa ŭi koch’al,” [A study on the painting of Kṣitigarbha in the late Koryŏ and the early Chosŏn period], Kogo misul [Archeology and Art History] 157 (1983), 32–47; Kim Junghee (Kim Chŏng-hŭi), Chosŏn sidae Chijang-siwangdo yŏn’gu [A study on the painting of the Kṣitigarbha and the Ten Kings of Hell in the Chosŏn period] (Seoul: Ilchisa, 1996); Kim Junghee (Kim Chŏng-hŭi), “Han-Chung Chijang tosang ŭi pigyŏ koch’al: Tugŏn-Chijang ŭl chungsim ŭro,” [A comparative analysis of the image of Kṣitigarbha in Korea and China: In relation to the hooded Kṣitigarbha], Kangjwa misulsa [The Art History Journal] Vol 9 (197), 63–103; Park Chanhee (Pak Ch’an-hŭi), “Chosŏn chŏn’gi t’ap pong’an Chijang posalsang yŏn’gu,” [A study of the stupā enshrined Kṣitigarbha images in early Chosŏn] (MA thesis, Tongguk University, 2005); Namgung Sara, “Yŏmal sŏnch’o Chijang posalsang yŏn’gu,” [A study on the Bodhisattva Kṣitigarbha sculptures of the late Koryŏ and early Chosŏn period] (MA thesis, Ehwa Woman’s University, 2007). 9See Kim Junghee (Kim Chŏng-hŭi), Ibid., 32–47. 10About the Great Monk Sengqie and the belief that he is the incarnation of Avalokiteśvara, see Yü Chün-fang, Kuan-yin: The Chinese Transformation of Avalokiteśvara (New York: Columbia University Press. 2001), 211–222. 11For more on Sengqie belief, the following texts can be consulted. Makita Tairyo, “Chukoku ni okeru minzoku Bukkyo seiritsu no ichikatei - Shishu taisei sogawashyo ni tsuite · Tonkohon sandaishiden ni tsuite,” [The process of the establishment of Folk Buddhism in China; About Monk Sengqie, the Great Saint of Sizhou and The Stories of Three Great Monks from Dunhuang Scripture], Toho Gakuho (東方學報) 25 (1954), reprinted in Chukoku Bukkyo shi kenkyu [Studies on the history of Chinese Buddhism] 2 vols, Tokyo: Daito (1981–1984).; Ma Shichang, “Zhongguo gudai fujiao wenhua jiaoliu liangli,” [Two examples of the cultural exchange of ancient Buddhism in China], Silk’ŭrodŭ munhwa wa Han’guk munhwa [Cultures of the Silk Road and the culture of Korea] (Taejŏn: Ch’ungnam University Press, 1997). 12Representative entries vis-à-vis the cult of Sengqie can be found in Yi Ye’s “Records of Establishing the Sengqie Cave in Mt. Samgak” in Tongmunsŏn, Vol. 64. Translations follow the version of the Institute for Translation of Korean Classics. About the translations, see http://db.itkc.or.kr/index.jsp?bizName=MK&url =/itkcdb/text/nodeViewIframe.jsp?bizName= MK& seojiId=kc_mk_c006&gunchaId=av064&muncheId=01&finId=010&NodeId=&setid=2059225& Pos=0&TotalCount=1&searchUrl=ok. and in the History of Koryŏ (Koryŏsa ). 13Kim Kyonghye (Kim Kyŏng-hye), “Sajabinsin saji sŏkt’ap Sŭnggasang koch’al” [A study on the stone statue on the pagoda at Sajabinsin Temple: noting its iconographical relation to the hooded Kṣitigarbha] (MA thesis, Korea University, 2010). 14Ibid., 15–40. 15Zan ning, Songgaoseng-chuan (Biographies of Eminent Monks in the Song period) (988). T2061, 50: 822-823. 16Nam Dongsin (Nam Tong-sin), “Pukhan-san Sŭngga taesa-sang kwa Sŭngga sinang,” [A study on the granite Sŭngga of Sŭngga Temple on Mt. Pukhan and the Sŭngga Faith], Seoulhak yŏn’gu [The Journal of Seoul Studies] 14 (2000), 5–48. 17The inscription “沙州大聖” is found on the wall of Cave 177. Based on evidence from the text written outside the cave, it is thought to date from either 1066 or 1126. Zhongguo meishu quanji; diaosu pian 12 - Sichuan shiku diaosu [Catalogue of Chinese art works; sculpture 12 - Sichuan grotto sculpture] (Beijing: Beijing renmin meishu chubanshe, 1988). 18This main Buddha is a good comparison to the previously mentioned image in Minch’ŏn Temple at Kaesŏng. Choe Song-eun (Ch’oe Sŏng-ŭn), “Minch’ŏn-sa kŭmdong Amit’a puljwasang kwa Koryŏ hugi Pulgyo chogak,” [Minch’ŏn Temple’s gilt bronze statue of Amitabha and Buddhist sculpture in the late Koryŏ period], Kangjwa misulsa [The Art History Journal] Vol. 17 (2001), 25–45. 19Park Chanhee (Pak Ch’an-hŭi), ibid., 35–53. 20From the year 894—when Sengqie appeared in dreams and warned of attacks from enemies—no temple lacked images of Sengqie. Great Monks of Song 18 (T2061, 50: 822b). Another study focusing on this issue is that of Kim Kyonghye (Kim Kyŏng-hye), ibid., 45–50, which quotes the records of Japanese monks and classifies prayers for a safe sea journey, which are also a part of Sengqie belief. 21For more information on the Naksaeng-yŏk (horse-changing station) and the P’an’gyo-jŏm (Official lodge), refer to Sŏngnam Cultural Center ed., Sŏngnam ŭi munhwa yusan [History of the cultural heritage of Sŏngnam] (Sŏngnam: Sŏngnam Cultural Center, 2001), 75–84. 22Sŏngnam Cultural Center ed., ibid., 55–60; Sŏngnam Cultural Center ed., Naksaeng maul-chi [Records of Naksaeng Village] (Sŏngnam: Sŏngnam Cultural Center, 2009), 26–40. 23The written works of Yi Ye (李預), the Chijunch’uwŏnsa (知中樞院事) in 1092 and later the Hyŏngbusangsŏ (刑部尙書), constituted important information. Yi Ye, “Samgak-san chungsu sŭnggagul-gi,” [Records of establishing the Sengqie Cave in Mt. Samgak] in Tongmunsŏn, Vol. 64. Translations follow the version of the Institute for Translation of Korean Classics. Concerning the translations, see http://db.itkc.or.kr/index.jsp?bizName=MK& url=/itkcdb/text/nodeViewIframe. jsp?bizName=MK&seojiId=kc_mk_c006&gunchaId=av064&muncheId=01&finId=010&NodeId=&setid=2059225&Pos=0&TotalCount=1&searchUrl=ok. 24Yi Ye, ibid. 25King Munjong sent his envoys to Song in 1072. It was 26th year of King Munjong. See Kugyŏk Koryŏsa [Translated History of Koryŏ] vol. 3, Seoul: Kyŏngin Publishers (2006) 26For more about the cult of Sengqie in Koryŏ, see Nam Dongsin (Nam Tong-sin), ibid., 5–48. 27See the compilation from the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage on the stone stupā of Kŭmjang Temple. National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage ed., Sajin ŭro ponŭn Pukhan kukpo yujŏk [Photographs of National Treasures in North Korea] (Taejŏn: National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, 2006), 138. It is also thought that images of Sengqie would have been present in Kwaesŏk-ri in Hongch’ŏn, and on the four-lion stone stupā in Churi Temple in Haman. For further information, refer to Kim Kyonghye (Kim Kyŏng-hye), ibid., 63–66. 28The Piṇḍola-Bhāradvāja statue has been estimated to be from 1027 at the earliest, in relation to the establishment of the Yŏngt’ong Temple. However, the author disagrees with this estimation: in comparing it to the image in the stone stupā in Sajabinsin Temple site—which can be precisely dated to 1022—the stylistic differences are too great. For more information on Arhat beliefs, refer to Choe Song-eun (Ch’oe Sŏng-ŭn), “Uri nara ŭi nahan chogak” [Arhat images of Korea], Nahan [Arhat] (Ch’unch’ŏn: Ch’unch’ŏn National Museum, 2003). 29“Shanghai shi Songjiang xian Xingjiao si ta digong fajue jianbao,” [A brief report on the excavation of Xingjiao Temple Stupā at Songjiang County in Shanghai City], Kaogu [Archeology] 2 (1983). 30Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation ed., ibid., (2008), 2. This includes twelve indistinguishable coins. 31Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation ed., ibid. (2008), 2. 32For the warfare at that time, see Yun Yonghyeok (Yun Yong-hyŏk), “1232 nyŏn Yongin Ch’ŏin-sŏng esŏ ŭi tae-Mong sŭngch’ŏp,” [The great victory against the Mongols at Ch’ŏin Fortress in Yongin, 1232], Yŏ-Mong chŏnjaeng kwa Kanghwa tosŏng yŏn’gu [Study on the Kanghwa Fortress and the Koryŏ-Mongol War] (Seoul: Hyean, 2011). 33“As the Mongol army headed towards Kwangju, Ch’ungju and Chŏnju, everyone in these places was killed and exterminated” December in the 18th year of King Kojong, Koryŏ. Kukyŏk Tong’guk- t’onggam [Translated History of the Eastern Country, Korea], King Sejong Commemorative Association (1996); “A 3,000-man Mongol army camped in Koju (Kowŏn County, South Hamgyŏng Province) and Hwaju (Kŭmya County, South Hamgyŏng Province), from which 300 scout troops ventured out to Kwangju (Kyŏnggi Province) and set fire to villages,” 40th year of King Kojong (1253) Kukyŏk Koryŏsa [Translated History of Koryŏ], Seoul: Kyŏngin Publishers (2006). The same content also appears in History of Korea. 34This is still a ritual regularly conducted in Buddhist temples which uphold the traditions of placing importance on the Amitābha ritual, the Avalokiteśvara ritual, and the Kṣitigarbha ritual. 35“By applauding and reciting the name of the Bodhisattva and creating images, one will not fall into the paths of evil.” Chijang posal ponwŏn-gyŏng [地藏菩薩本願經 Sutra of Kṣitigarbha], “Performing a ritual twice every month and creating an image for your parents will aid them in reaching the level of Saengch’ŏn (生天),” Pulsŏl yŏsu siwang saengch’il-gyŏng [佛說預修十王生七經]. 36Mun Sangryeon (Mun Sang-nyŏn), “Chijang sinang ŭi chŏngae wa sinang ŭirye,” [A study on the development and religious ceremonies of Bodhisattva Kṣitigarbha faith], Chŏngt’ohak yŏn’gu [Journal of Pure Land Buddhism] 15 (2011), 137–194. 37Kukyŏk Koryŏsa [Translated History of Koryŏ] Vol. 112, “Book of Biographies 25”. Wŏn (院) were established in relation to yŏk (驛), and the wŏn created in major transportation locations developed along with the economic activities of the land. The agents that established such inns were diverse and included the state, monks, and various individuals. However, monks constituted the major establishers of wŏn, because through them, the temple could gain economic dominance over the area’s commercial activities that were based on the wŏn. Sap’yŏngwŏn (沙平院) became a major commercial center by the thirteenth century because it was situated on the Han River, and P’an’gyo was no different. Cho Un-hŭl built a wŏn and established himself as the owner presumably because he wished to engage in commercial activities that would be to his advantage. Kwangju was reinstated to the status of a mok (administrative unit) in 1356; this was in part related to the activities of Cho Un-hŭl. This information was compiled by the Sŏngnam Cultural Center, ibid., 63; for a list of active members or people who retired in the P’an’gyo region, see Sŏngnam Cultural Center ed., Sŏngnam inmul-chi: Kwangbok ijŏn p’yŏn [People of Sŏngnam: Periods before Independence] (Sŏngnam : Sŏngnam Cultural Center, 2010). 38Sŏngnam Cultural Center ed., ibid. (2001), 57. 39Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation ed., ibid. (2008), chapter on the process and details of the survey. 40Korea Cultural Heritage Foundation ed., ibid. (2008), pp. 5-10.

III. CONCLUSION: FROM SENGQIE TO K?ITIGARBHA

The three statues excavated from Sŏngnam during the housing site development project were produced from the early Koryŏ period onwards. They were excavated from a small building site in Zone 10 of P’an’gyo District, at the end of a mountain range that descends to the east of Mt. Kŭmt’o. During the ground survey, the foundations of a building thought to date from the late Koryŏ–early Chosŏn period were confirmed in several places; thereafter, the excavation was conducted in three parts, with the ground being divided by topography. Three statues were excavated from the eastern range of the mountain in Area C of Zone 10, which had been manufactured in different periods. They were a Vairocana Buddha with the

The iconography of the two statues with hands held together in prayer is not clear. It is possible that they are images of Kṣitigarbha, Sengqie, or an arhat, but none display any one typical iconography. This article starts from the hypothesis that the statues unearthed in P’an’gyo were created as Sengqie images and later came to be venerated as Kṣitigarbha images. These sculptures were buried as Kṣtitigarbha in the figure of Sengqie. All three statues show stylistic differences from other sculptures of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, most of which indicate that these three statues cannot be from this period. From the excavation site, several fragments of inlaid celadon bowls, a bronze mirror, and Northern Song coins in circulation during the tenth to twelfth centuries were recovered, and this indicates that the statues are from the same period as these artifacts; this hypothesis is further supported by the fact that the Sengqie images are similar in style to two eleventh-century statues. Therefore, the sculptures excavated from P’an’gyo can be dated as being from the early twelfth century. The two images with their hands held together in prayer were created by borrowing from the iconography of Sengqie; this was a widespread trend in Song China at this time. Later, reflecting the history of the P’an’gyo region, the images would have been worshipped as Kṣitigarbha by the fourteenth century.

The development of Kṣitigarbha belief was natural and accorded with changes in society. This development was also the reason for the wide distribution of Kṣitigarbha images in late Koryŏ Buddhist paintings and sculptures. During the Mongol invasions, the region of Kwangju—including P’an’gyo and Naksaeng—was severely affected, and its entire population almost wiped out. Therefore, Kṣitigarbha belief concerning guiding the spirits of the dead would have acquired currency as the area rehabilitated. In this context we can assume that the images produced as Sengqie to “protect” the area during the twelfth century would have been worshipped as Kṣitigarbha by the end of the Koryŏ period. From the beginning, Kṣitigarbha was worshipped by members of the general public who wished for salvation in the afterlife. The popularity of Kṣitigarbha belief during the late Koryŏ-early Chosŏn period—at a time when the country had suffered greatly from Mongol attacks—can be confirmed by the existence of Kṣitigarbha images that have survived from that period. The three statues, all of which are difficult to analyze solely on the bases of style and iconography, deserve attention, as they are uncommon examples of early Koryŏ period images. The images excavated from P’an’gyo show not only distinct regional characteristics, but are important examples that reveal local beliefs of the late Koryŏ period.

![Tongy?do [Map around P’an’gyo Area], Late Chos?n Period](http://oak.go.kr/repository/journal/17703/NRF003_2014_v17n1_223_f010.jpg)