The welfare state in Chile was transformed from a system with comprehensive benefits that was heavily funded by government revenues into one where benefits were significantly limited and regulated by market forces. Welfare policy has recently evolved into a quasi-comprehensive system in which state subsidies and benefits have been expanded but guided by the logic of the private market. These dynamics are largely the result of the interplay between the variation of Chile’s integration into the global economy and the variation in the nature of its domestic political system, which witnessed a transition from democratic governance to authoritarianism and then the resumption of democratic practices after sixteen years of military rule.

The Chilean social policies implemented since 1920 with the purpose of improving living standards of the lower income classes of the population were fundamentally reformed after the 1973 military coup. The military junta terminated most of the socially-oriented state programs to give place to the new market-oriented social and economic order efficiency. The political regime change to democracy in 1990, when the democratic coalition, Concertación, defeated Pinochet at the 1989 presidential election, did not recover any similar kind of state-organized equal economy. However, the following democratic Concertación regimes were different from the military junta in that they significantly expanded public welfare programs to compensate the economic dislocations generated from economic globalization.

What explains the transition of Chile’s social welfare policies, given that its national economy was being increasingly integrated into the global economy? In answering this question, a dominant theoretical approach in the literature—often referred to as the

Other scholars posit what they claim to be an alternative theory: the

Based on such debates, this study pinpoints the mechanism that transformed Chile’s welfare state by comparing the pressures related to global economic integration and political transition under Pinochet and Concertación regimes, and contributes to the existing literature by drawing upon efficiency and compensation approaches and developing a mediated theoretical framework that explains globalization’s effects on social spending. This article begins with a historical overview and then highlights the ways in which Chile’s democratic regimes developed a comprehensive welfare state. It then examines how the economic stabilization and trade liberalization policies of the military junta globally integrated the economy and in the process replaced Chile’s traditional welfare state with one that featured significantly limited benefits that were regulated by the free market. This is followed by a discussion of the restoration of democracy in Chile and the creation of a quasicomprehensive welfare state under conditions of greater global economic integration and the political dominance of the Concertación regime, which is composed of a ruling coalition of center-left political parties. The study concludes with a discussion of the future challenges to Chile’s welfare state.

Chile achieved independence from Spain in 1810 and by 1925 established an electoral democracy that ended in 1973. Throughout much of this period, various governments attempted to reform Chile’s social and economic system by pursuing the import-substitution industry (ISI), trade protectionism, expanding the welfare state and statist policies that sought to nationalize key industries. These statist policies were reinforced following the election of Eduardo Frei of the Christian Democratic Party (PDC) in 1964. The government acquired majority ownership of the copper industry, redistributed land, and expanded access to education. Despite these changes Chile’s political left pressed for more radical reforms, which in 1970 culminated with the election of Salvador Allende of the Popular Unity party. The Allende government accelerated the reforms of the Frei administration by fully nationalizing the copper and telecommunication industries and expanded land reform and the welfare state. The PDC allied with Chile’s parties on the right to block the legislative initiatives of Allende’s Popular Unity government. The ideological gridlock prevented the government from addressing the economic depression. Unemployment and inflation increased, while international capital flows to Chile plummeted. As the economy continued to deteriorate along with the indecisive outcome of the 1973 legislative elections, the military intervened on September 11.1)

The Chilean military, led by General Augusto Pinochet, deposed the Allende government in a violent coup and terminated democratic practices and civil liberties and regarded the organized left as an internal enemy of the state. In 1978, General Pinochet won a tightly controlled referendum, which institutionalized the junta’s rule. The military regime implemented a series of neoliberal economic reforms that liberalized trade and investment, privatized state holdings in the economy, and dismantled the comprehensive welfare state. In 1980, General Pinochet won another referendum that approved the new Constitution, which called for a plebiscite in 1988. Chileans were given the opportunity to reelect Pinochet to another 8-year term or reject him in favor of contested democratic elections. The collapse of the economy in 1982 sparked a nationwide protest against the military junta, which helped to galvanize opposition to Pinochet’s reelection among Chile’s political parties. In the ensuing plebiscite, 55% of the Chilean people rejected eight more years of military rule and called for democratic elections in 1989.2)

Two major coalitions of parties emerged to contest the 1989 elections. These included the center-left Coalition of Parties for Democracy, or Concertación, and the center-right Democracy and Progress coalition. Patricio Aylwin, a Christian Democrat and the candidate of the Concertación, won the presidency with 55% of the votes and the Concertación won majorities in the Chamber of Deputies and among the elected members of the Senate. The Concertación coalition has governed Chile continuously since the transition to democracy. Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle was elected president in 1993, followed by Ricardo Lagos in 1999, and Michelle Bachelet in 2005. While the Concertación coalition governments maintained the neoliberal economic policies of the Pinochet regime, they have also implemented social programs, although at much reduced levels than the Allende era, to reduce poverty and expand access to education and health care.3)

1)Simon Collier and William F. Sater, A History of Chile, 1808-1994, Cambridge Latin American Studies 82, 2nd ed. (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996). 2)Pamela Constable and Arturo Valenzuela, A Nation of Enemies: Chile under Pinochet (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1993). 3)John L. Rector, The History of Chile, Palgrave Essential Histories (Houndsmill, Baskingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005).

The fundamental proposition of efficiency theory is that high levels of government social spending undermine economic efficiency and the competitiveness of domestic firms in international markets.4) It is argued that since social spending is largely funded by corporate taxes, any increase in social expenditures will be accompanied by an equivalent increase in taxation levels. Increased taxes undermine investor confidence and the competitiveness of domestic companies, in both domestic and international markets.5) Increased social spending can also result in increased government debt, especially as the state increases its borrowing to finance welfare policies. Consequently, increased government borrowing results in higher interest rates and the devaluation of the currency, both of which increase production costs and discourage companies from making new investments.6)

High taxation levels brought about by increases in spending vis- ` a-vis government welfare policies will ultimately facilitate capital flight, as transnational corporations will begin relocating their investments to countries that have lower taxes and limited social protections. This produces a “race to the bottom” effect on the welfare state.7) Since economic globalization increases the mobility of transnational capital, it is this threat that forces governments to reduce social expenditures significantly, in order to restore investor confidence. In summary, the efficiency-theory model posits that economic globalization and the level of international competition that emerges from it constrain and limit government welfare spending in order for the state to attract and retain mobile capital.

While recognizing the budgetary constraints of the state under conditions of increased global economic integration, compensatory approaches to welfare spending emphasize social demands with respect to welfare allocation, and the political incentives of policymakers in responding to such demands. The welfare system, according to this approach, is a necessary mechanism for offsetting the costs of global economic integration.8)

Scholars in this tradition argue that efficiency theories overlook the political incentive to increase public programs in response to international economic integration.9) Since policymakers in democracies are primarily motivated by reelection, they are more likely to increase welfare spending to offset negative economic externalities—for example, job losses and increased income inequality—that result from the competitive nature of the global economy. Hence, knowing that those who are displaced will blame political incumbents for the adverse externalities of economic globalization, policymakers are more likely to increase welfare spending to pacify, for example, displaced workers. In addition, policymakers will also provide welfare benefits to ensure that the adverse externalities of global economic integration will not disrupt national financial markets.10)

The existing literature has produced evidence that cannot be generalized across countries. Studies on Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries suggest that increasing levels of global economic integration increases government welfare expenditures—a hypothesis consistent with the compensation thesis.11) Meanwhile, studies on the countries in the developing world suggest that increasing levels of economic globalization significantly reduces government welfare spending, as predicted by efficiency theories.12)

While the existing literature treats efficiency and compensation approaches as competing or mutually exclusive ‘theories’ of the welfare state, they are considered here to be mutually inclusive processes in the development of social policy. Government welfare policy emerges from the tension of globalization’s proclivity to retrench social spending and the proclivity of domestic political actors and institutions to compensate. In essence, the construction of social policy, under conditions of global economic integration, is a function of the dialectical pressures for greater economic efficiency and domestic political preferences for greater compensation.

This study argues that government welfare spending is a function of the ways in which the pressures of economic globalization is conditioned by domestic politics. Domestic politics factors include political regime type and political ideology of the ruling party. Political regime type determines the political environment that shapes the incentives of government officials who make welfare policies. The ruling party’s ideology determines the preferences of government leaders who make welfare policies: how government resources—specifically welfare expenditures—are distributed. This study, therefore, examines how economic globalization’s effect on the Chilean welfare state is conditional on the domestic political environment.

The dependent variable is social policies of different political regimes and the main explanatory variables are political regime type and political ideology of the ruling party. The dependent variable is measured by the social expenditures of each government.13) Political regime type is measured with dichotomous democracy/authoritarianism classification. Political ideology of the ruling party is measured with dichotomous leftist/rightist classification. The theoretical argument of this study is examined through the Chilean case which provides the examples of contrasting authoritarian Pinochet government and democratic Concertación government under increasing economic globalization.

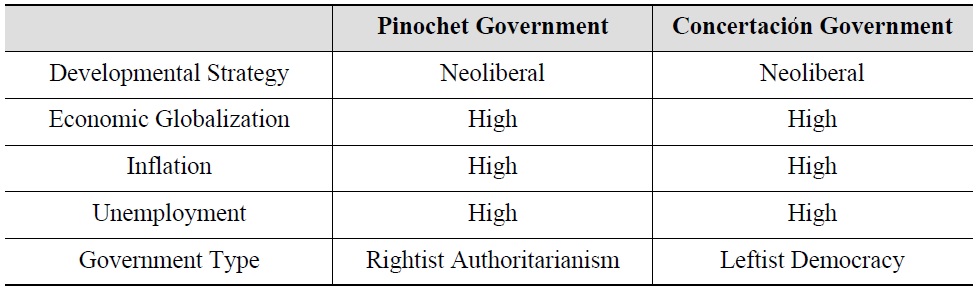

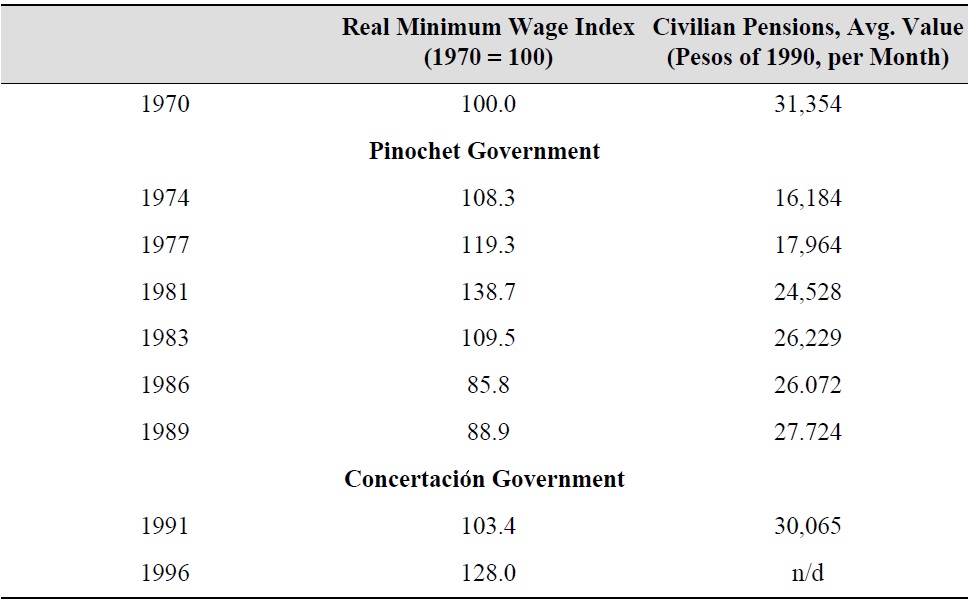

[Table 1.] Comparison of the Political and Economic Environments

Comparison of the Political and Economic Environments

The two political regimes—Pinochet and Concertación regimes—in Chile provides appropriate conditions for a comparative study. Both regimes pursued neoliberal economic globalization opposed to the pre-coup ISI developmental policies. Both regimes also have similarities in that they suffered from economic crisis which increased poverty and unemployment. However, the two political regimes showed clear contrasting political environments. While Pinochet government was a rightist authoritarian regime, the Concertación government was a leftist democratic regime.

4)George Avelinon, David S. Brown, and Wendy Hunter, “The Effect of Capital Mobility, Trade Openness, and Democracy on Social Spending in Latin America, 1980-1999,” American Journal of Political Science 49-3 (2005), pp. 625-641; Geoffrey Garrett, Partisan Politics in the Global Economy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998); Robert R. Kaufman and Alex Segura-Ubiergo, “Globalization, Domestic Politics, and Social Spending in Latin America: A Time Series Cross-Section Analysis, 1973-97,” World Politics 53-4 (2001), pp. 553-587. 5)Geoffrey Garrett, op. cit. 6)Ibid. 7)Richard J. Barnet and John Cavanagh, Global Dreams: Imperial Corporations and the New World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994); Richard J. Barnet and Ronald E. Muller, Global Reach: The Power of the Multinational Corporations (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1974); Jeremy Brecher and Tim Costello, Global Village or Global Pillage: Economic Reconstruction from the Bottom Up (Boston: South End Press, 1994). 8)David R. Cameron, “The Expansion of the Public Economy,” American Political Science Review 72-4 (1978), pp. 1243-1261; Robert R. Kaufman and Alex Segura-Ubiergo, op. cit.; Dennis Quinn, “The Correlates of Changes in International Financial Regulation,” American Political Science Review 9-3 (1997), pp. 533-551. 9)Geoffrey Garrett, op. cit. 10)George Avelinon et al., op. cit. 11)David R. Cameron, op. cit.; Alexander M. Hicks and Duane H. Swank, “Politics, Institutions, and Welfare Spending in Industrialized Democracies, 1960-82,” American Political Science Review 86-3 (1992), pp. 658-674; Torben Iversen and Thomas R. Cusack, “The Cause of Welfare State Expansion: Deindustrialization or Globalization,” World Politics 52-3 (2000), pp. 313-349. 12)George Avelinon et al., op. cit.; Robert R. Kaufman and Alex Segura-Ubiergo, op. cit.; Nita Rudra, “Globalization and the Decline of the Welfare State in Less-Developed Countries,” International Organization 56-2 (2002), pp. 411-445. 13)This study uses social spending as a share of GDP as a measure of the dependent variable. This data was complemented by total amount data in constant value.

Ⅳ. Comprehensive Welfare State under Closed Economy

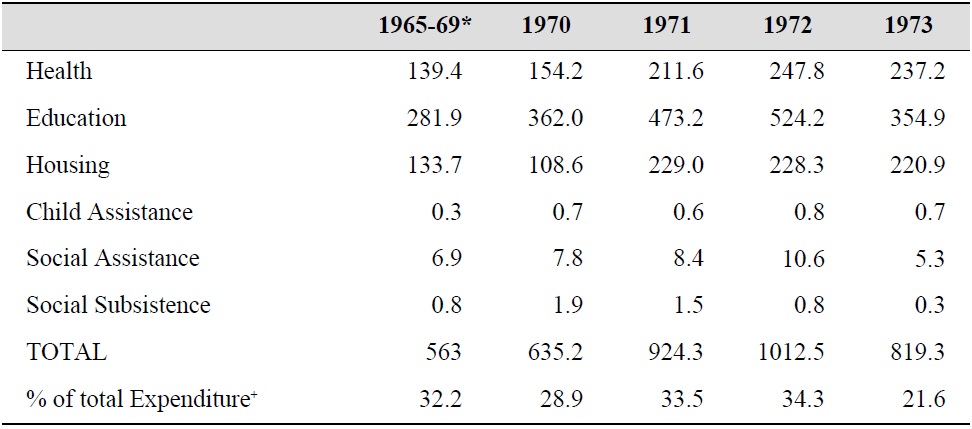

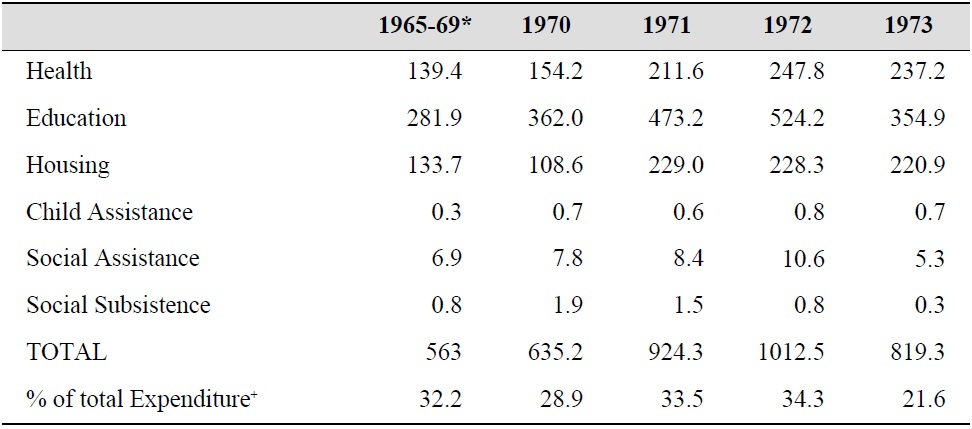

From the 1930s to the mid-1970s, Chile’s import substitution model of industrial development involved the use of discriminatory tariffs, exchange rate controls and tax policies to help establish national industries and protect them from overseas competition. During this period, Chile’s ISI strategy was intimately connected with its Bismarckian welfare state, in that the state tried to provide a comprehensive welfare to win the support of the working classes for the protectionist economic policies. The Bismarckian welfare state was also beneficial to capital because it provided a stable labor force for the domestic industry. The ISI strategy to nationalize industries also involved Chile’s welfare state.14) During the period of the Allende government’s largest nationalization initiatives, social spending for each year from 1970 to 1973 more than doubled the annual average of the previous four years.

By 1971, the Allende government unified the health-care systems into the

[Table 2.] Social Spending during the Allende Government (millions US dollar)

Social Spending during the Allende Government (millions US dollar)

The nationalization initiatives of the state were also used to provide the working classes with employment and salary increases as well as empower the labor unions. In 1970, the Allende government signed an agreement with one of the country’s largest unions, the Central Workers Union, which provided for the participation of workers in the planning and the administration of state-owned and mixed corporate enterprises, the reduction of unemployment by the provision of 180,000 jobs and the creation of a Central Committee on Wages and Salaries to formulate new wage and salary policies.

By the early 1970s, growing evidence suggested that Chile’s ISI strategy and the welfare state that it supported was financially unsustainable. Social spending per person, between 1920 and 1970, increased by 38%, while GNP per capita increased by only 2.3%.16) Trade protectionism provided no incentive for domestic firms to become efficient, but merely encouraged rent seeking behavior. The crisis in the macroeconomy led to a significant decline in tax revenues, which severely eroded the state’s ability to finance its increasingly costly social programs. With the growing economic crisis and political polarization within the Allende government, the military junta staged a coup d’eta on September 11, 1973.17)

14)Lester A. Sobel, Chile & Allende (New York: Facts on File, Inc., 1974). 15)Rex A. Hudson, Chile: A Country Study (Washington, DC: GOP for the Library of Congress, 1994); Maria Angelica Illanes and Manuel Riesco, “Developmentalism and Social Change in Chile,” in Manuel Riesco (ed.), Latin America: A New Developmental Welfare State Model in the Making? (New York: Palgrave Macmillan/UNRISD, 2007). 16)José-Pablo Arellano, “Social Policies in Chile: An Historical Review,” Journal of Latin American Studies 17 (1985), pp. 397-418. 17)Ricardo Zipper Israel, Politics and Ideology in Allend’s Chile (Tempel, AZ: Arizona State University Press, 1989).

Ⅴ. Retrenched Welfare State: Economic Globalization and Authoritarian Regime

To arrest the economic crisis the rightist authoritarian government of military junta drastically reduced the welfare state. In formulating an economic strategy the junta relied heavily on the advice of the Chicago Boys, a group of Chilean neoliberal economists who were trained at the University of Chicago under Milton Friedman and Arnold Harberger. The economic policies that were advocated by the Chicago Boys ended decades of ISI development in Chile and the comprehensive welfare state that it induced. The junta’s economic policy was based on three objectives: the stabilization of the economy, the liberalization of trade, and the privatization of state holdings.18)

The stabilization policy involved a two-part strategy. Often referred to as ‘shock treatment’, the first part of the stabilization policy sought to eliminate inflationary pressures by cutting the fiscal deficit by 25% within the first six months of the military dictatorship. The reduction of the fiscal deficit involved the retrenchment of public sector jobs and across the board cuts in the social programs of the welfare state.19) Second, the stabilization policy also concentrated on arresting the balance of payments crisis by securing external financing from international creditors. By January 1974, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) approved a stand-by arrangement that allowed Chile to borrow US $94.8 million over 12 months to overcome the foreign exchange deficit of its balance of payments. In April of that year the Inter-American Development Bank approved a US $73.3 million loan to Chile, which previously had been denied back in 1972 (during the Allende government). For its part, the US government also extended loans totaling US $52 million to finance Chile’s imports of American corn and wheat.20)

The junta’s liberalization policy dismantled the Allende government’s differentiated tariff structure of rates between 10% and 35%. The objective was to reduce tariffs to a uniform rate of 10% by 1979.21) In fact, the junta successfully implemented its trade reforms by significantly reducing tariffs from their 1973 levels to 10% by 1979. However, this pattern was temporarily suspended in 1982-1983, when Chile experienced its worst economic crisis since the 1930s. The junta also gradually reduced and eventually eliminated import prohibitions and import licenses. The trade reforms found strong political support among export-oriented industries that were unable to realize economies of scale under ISI. Since trade liberalization lowered the price of imported inputs of production, the reform also benefited firms in the construction and transportation industry which participated in several industrial strikes against the Allende government.22)

The junta implemented privatization policies by announcing that 115 nationalized companies would be returned to their former owners. The first of these companies were four US-owned motion picture distributors, the USowned General Tire International, and Dow Chemical. Chile’s State Development Corporation announced that another 88 business and industries would also be returned to their former owners because they were illegally expropriated by Allende’s Popular Unity government.23) On December 1974, the junta passed a decree that prohibited the state ownership of commercial banks.24)

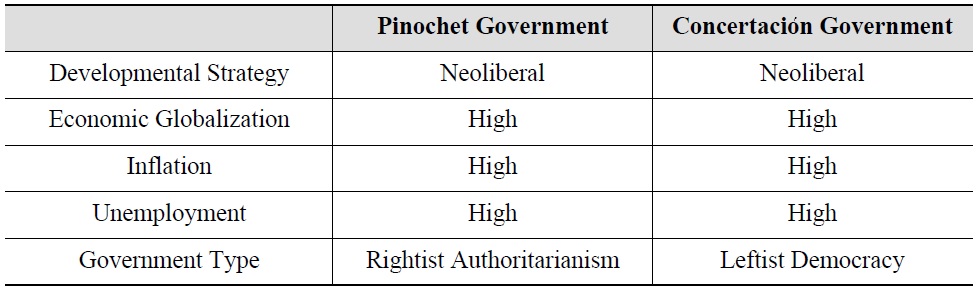

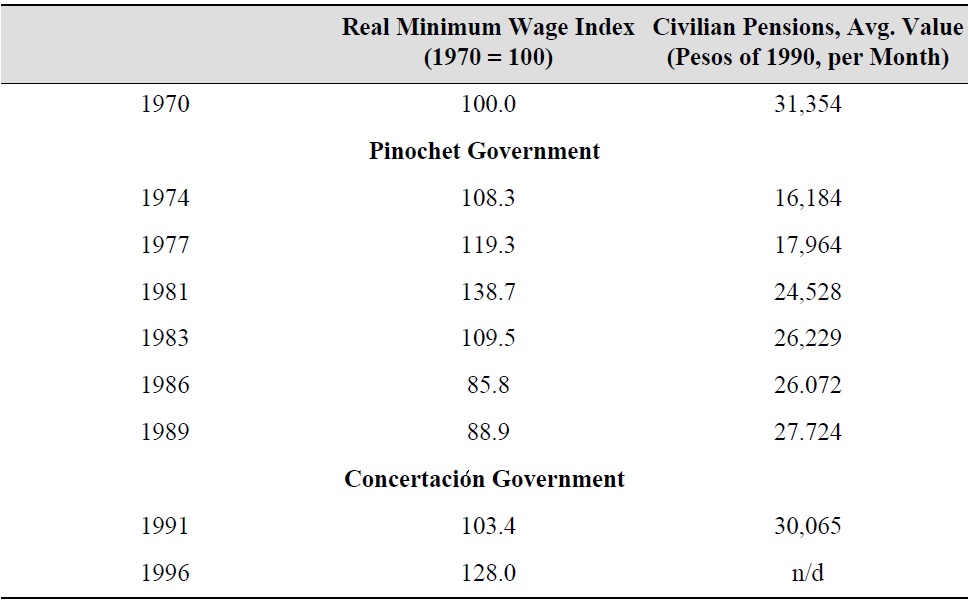

The junta’s privatization policies, which also liberalized the capital markets, were reinforced by the repression of labor unions that aligned themselves with the Allende government. On September 18, 1973, the junta issued a decree that banned the presentation of union demands and suspended the right of union leaders to use paid working hours to address union issues. Other decrees were issued that made it easier for private firms to fire workers, including the firing of workers who lead in what the junta considered illegal strikes. The junta’s anti-labor diktat also suspended unions’ rights for collective bargaining and the automatic adjustment of pensions to compensate for inflation.25) Consequently, union membership drastically declined from 65% of Chile’s total wage earners in 1973, the last year of the Allende government, to less than 20% on average for the entire 1980s.26)

The neoliberal stabilization policies that slashed the fiscal deficit achieved their objective by drastically reducing inflation from a high of 605.9% in 1973 to 21% in 1989, the last year of military rule in Chile. Controlling inflation and the stabilization of prices allowed Chile’s industry to achieve greater economies of scale as they benefited from the privatization of capital markets and trade liberalization, which effectively integrated Chile into the global economy. As a result, Chile’s annual growth rates during the years of military rule, with the exception of 1982-1983, exceeded the growth rates of the previous democratic governments as well as its Latin American neighbors and established the economic conditions that have sustained growth into the transitional years under democratic rule.

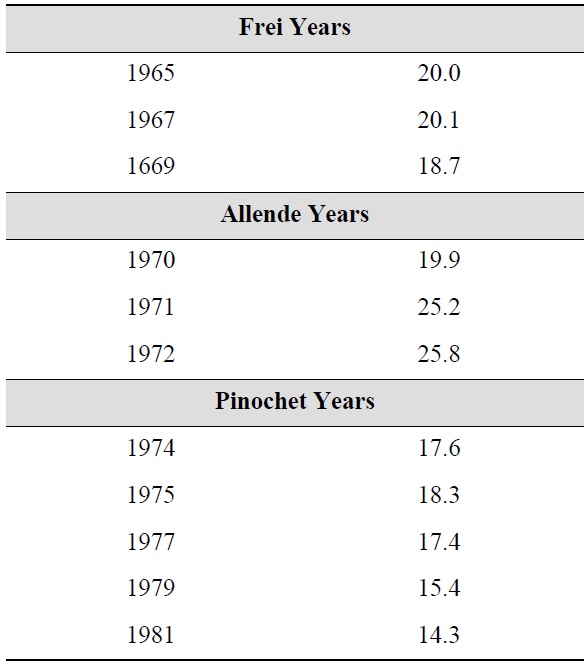

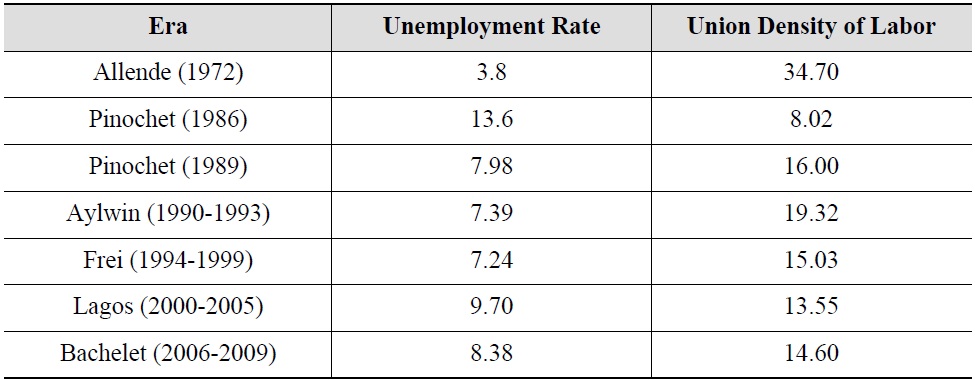

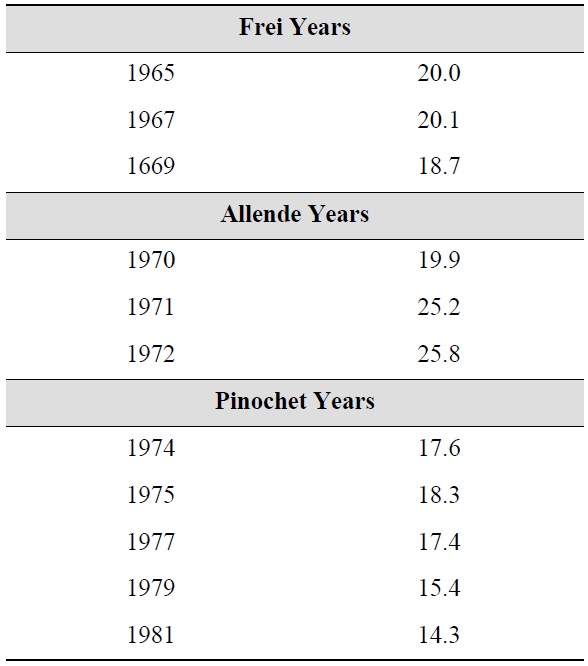

The success of the military junta’s neoliberal policies in globalizing the economy came at the expense of Chile’s welfare state and ended five decades of continuous social spending that had been financed by public revenues. While the neoliberal market forces emphasizing economic efficiency dominated domestic socioeconomic policies, the authoritarian government did not find any incentive to compensate the losers of the economic globalization. As a consequence of the junta’s stabilization policies to reduce inflation, social spending as a proportion of GNP was reduced from 20% in the second half of the 1960s to 14% by the start of the 1980s. Combined with the junta’s privatization policies, the allocation of education, housing, and social security was largely determined by market forces with increased participation by the private sector.

In terms of education reform, the junta drastically reduced expenditures on public schools and placed the burden of administering and supporting the education system on local municipalities and parents. Between 1980 and 1990, government spending on education was cut by 27%. Instead, in 1981, the junta introduced a nationwide school voucher program that gave parents the choice between sending their children to private or public schools. The program created a dynamic market for education with more than a thousand private schools entering the market for profit, which increased private enrollment rate from 20% to 40% by 1988 and exceeded 50% in Chile’s urban areas. Higher education was also market driven. The level of state funding to the universities was based on the proportion of students who entered universities with the highest scores on the national aptitude test. Universities were forced to compete for state funding in their effort to recruit the most qualified students. The higher education reform significantly reduced access to lower class students who could not afford university fees or whose test scores were not competitive to be recruited by the financially strapped universities.27)

The Allende government established

From the 1950s, the state played a major role in Chile’s low-cost housing development and built 60% of the houses between 1960 and 1972. The junta drastically slashed public spending on housing to less than half of its 1970 levels, which increased Chile’s housing deficit. In addition, the junta also reduced subsidies on housing loans and increased the participation of the private sector in the development of new homes and municipal buildings. Housing was also allocated to income groups that met certain savings goals, which effectively reduced poor families’ access to housing since they could not meet the junta’s savings criteria.29)

The military junta closed the previously unfunded

[Table 3.] Government Social Spending, 1961-1981 (% GDP)

Government Social Spending, 1961-1981 (% GDP)

While Chile’s privatized pension system has been hailed as a success and a model for pension reform, the new system was limited in its coverage. Before the junta’s privatization, the coverage of the public pension system accounted for 72% of the population, while the private pension system covered just 60% by 2000. The problem of coverage is rooted in the structure of Chile’s labor market, which is characterized by high levels of self-employment (28% of Chile’s labor force) and an informal labor force. Among the self-employed, only 4% were engaged in the new pension system in 2000 and 1.5 million self-employed workers were not enrolled in the system.34) The 10% mandatory employee contribution coupled with the nature of Chile’s labor market reduces the incentive for low-wage workers to contribute to the privatized pension system.

As a result, only a minority from Chile’s labor force makes regular contributions to the pension system, which reduces the likelihood that participants will accumulate sufficient funds in their personal accounts to maintain a minimum standard of living upon retirement. In 2006, projections that were based on the history of worker contributions demonstrated that a large share of the pension system’s participants would indeed face financial hardship upon retirement. And 45% of participants would also have pensions below the minimum pension guarantee threshold and would not have met the level of contribution required to qualify for the subsidized government benefit.35) An additional problem with the privatized pension reforms is that the high administrative costs, which reduce retirement benefits, also had a negative effect on the level of participation in the system. Administrative cost that is paid to pension fund managers reduces the rate of benefits from 12.7% before the reforms to 7.4% after their implementation.

18)Raul Laban and Felipe Larrain, “Continuity, Change and the Political Economy of Transition in Chile,” in Rudiger Dornbusch and Sebastian Edwards (eds.), Reform, Recovery, and Growth: Latin America and the Middle East (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1995), pp. 115-148; Eduardo Silva, “Capitalist Coalitions, the State, and Neoliberal Economic Restructuring: Chile 1973-88,” World Politics 45 (1993), pp. 526-559. 19)Milton Friedman, Letter to General Pinochet on Our Return from Chile and His Reply (Santiago, Chile, 1975). 20)Lester A. Sobel, op. cit. 21)Sebastian Edwards and Daniel Lederman, “The Political Economy of Unilateral Trade Liberalization: The Case of Chile,” NBER Working Paper Series (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1998). 22)Ibid.; Guillermo Campero, “Entrepreneurs under the Military Regime,” in P. W. Drake and I. Jaksic (eds.), The Struggle for Democracy in Chile, 1983-1990 (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1991). 23)Lester A. Sobel, op. cit. 24)Sebastian Edwards and Daniel Lederman, op. cit. 25)José-Pablo Arellano, op. cit.; Manuel Barrera and J. Samuel Valenzuela, “The Development of Labor Movement Opposition to the Military Regime,” in J. Samuel Valenzuela and Arturo Valenzuela (eds.), Military Rule in Chile: Dictatorship and Oppositions (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), pp. 230-269. 26)René Cortázar, “The Evolution and Reform of the Labor Market,” in S. Edwards and N. Lustig (eds.), Labor Markets in Latin America: Combining Social Protection with Market Flexibility (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 1997). 27)José-Pablo Arellano, op. cit. 28)Simon Collier and William F. Sater, op. cit.; Raul Laban and Felipe Larrain, op. cit. 29)Rex A. Hudson, op. cit. 30)Mauricio Soto, “The Chilean Pension Reform: 25 Years Later,” Pensions: An International Journal 12-2 (2007), pp. 98-125. 31)Silvia Borzutzky, “Social Security Privatization: The Lessons from the Chilean Experience for Other Latin American Countries and the USA,” International Journal of Social Welfare 12 (2003), pp. 86-96; B. Kritzer, “Privatizing Social Security: The Chilean Experience,” Social Security Bulletin 59-3 (1996), pp. 45-55; O. S. Mitchell, “Social Security Reform in Latin America,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 80-2 (1998), pp. 15-18. 32)Silvia Borzutzky, “Chile: Has Social Security Privatization Fostered Economic Development?” International Journal of Social Welfare 10 (2001), pp. 294-299; Rossana Castiglioni, “The Politics of Retrenchment: The Quandaries of Social Protection under Military Rule in Chile, 1973-1990,” Latin American Politics and Society 43 (2001), pp. 37-66. 33)Silvia Borzutzky, 2003, op. cit.; B. Kritzer, op. cit.; O. S. Mitchell, op. cit. 34)Silvia Borzutzky, 2003, op. cit.; MIDEPLAN, “Ministra Krauss respondio a demandas de mujeres mapuches urbanas,” Press release (2000), available at

Ⅵ. Continued Globalization and the Expansion of Welfare Spending

In the 1988 plebiscite the Chilean people voted to reject eight more years of military rule in favor of democratic elections in 1989 that brought the Concertación coalition government, led by Patricio Aylwin, to office. The new government continued the neoliberalization economic policies of the junta and went even further in the process of integrating Chile into the global economy. Immediately upon taking office, the Aylwin government reduced the uniform tariff from 15% to 11% in 1991. The uniform tariff was unilaterally reduced even further from 11% (1999) to 6% (2003).36) And from 1997 to 2009, various Concertación administrations have also extended trade liberalization by negotiating a series of bilateral and multilateral free trade agreements. Currently, Chile has signed 13 free trade agreements, two free trade association agreements with MERCOSUR and the European Union, and five economic complementation agreements.

However, while continuing and in some respects deepening the free market policies inherited from the military junta, the Aylwin government and its successors also implemented changes in Chile’s social welfare policies. Under the military government, in spite of the high economic growth rates during the years of economic openness, the fruit of economic growth was not equally distributed to the people, and every globalized economic transaction exacerbated the rising inequality. For example, small and medium-size enterprises which were not prepared for the competition in the global market slowly but persistently collapsed, resulting in a doubling of unemployment figures. However, since the authoritarian government was based on the clientelistic support of the business sector, and not of the public, compensation for the losers of economic globalization was not a priority of the government policies. Chile’s ratio of total population under the poverty line (whose daily per capita income is less than one dollar) and Gini Coefficient during the last years of the military regime surged up to around 3837) and 57,38) respectively, which were around the world’s highest. Therefore, expansion of public spending to alleviate the economic inequality was one of the most urgent tasks for the new democratic Concertación government.

Furthermore, the extremely unequal distribution of income and wealth remained intact even under the new Concertación governments and the trend of social dislocation like poverty, unemployment, and inequality by economic globalization continued. This economic situation provided political motivations to compensate the losers for the new democratic governments which were based on the working class.

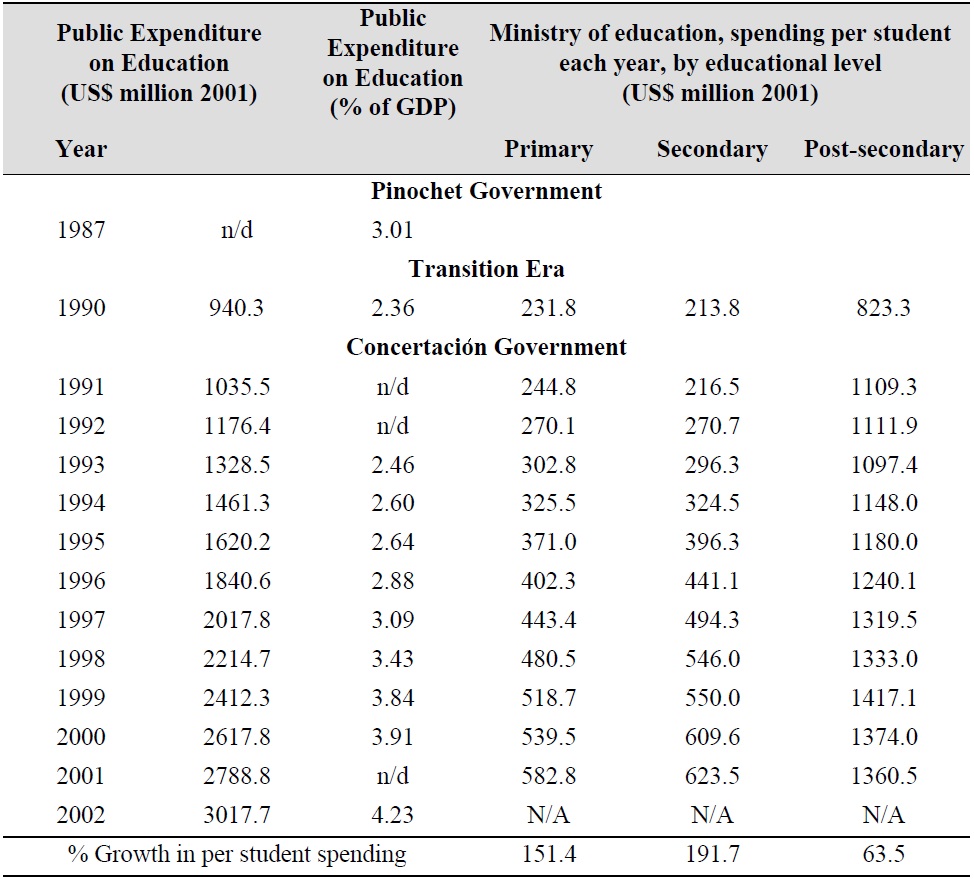

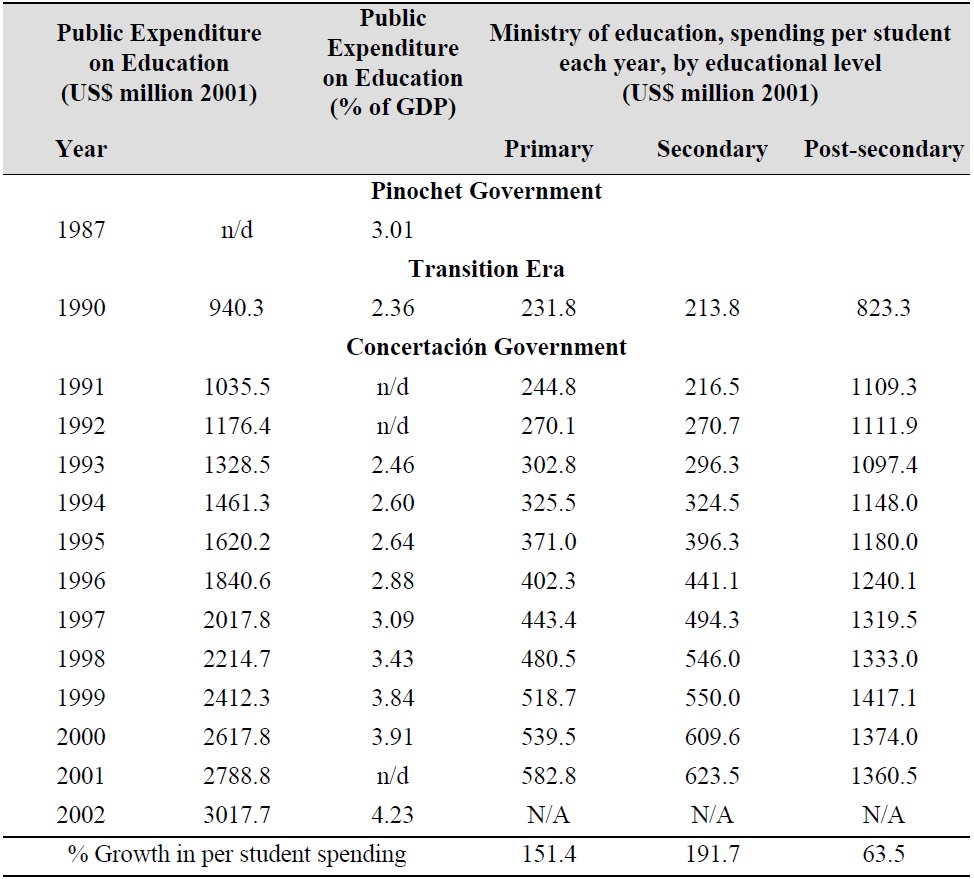

In terms of education the government expanded spending for elementary, secondary, and post-secondary schools. Public expenditure on education increased from US $940.3 million in 1990 to US $3017.7 million in 2001. Moreover, pubic spending per student in primary, secondary, and postsecondary schools almost tripled the amounts spent from 1990 to 2002 (see Table 4). Consequently, relative to the years under military rule, workingclass children have greater access to public education. The dropout rate among children from low income families were reduced from 4% for the first half of the 1990s to 2% in 1997.39) A marked improvement was also made in the learning performance among schools with different systems (municipal schools or government subsidized private schools) and these improvements were not biased in favor of private schools. The improvement in learning performance, access and retention rates among low-income children was also a result of the expansion and improved forms of social assistance. The expansion in government funded social assistance included food, health care, school-materials supply and grant programs. The main support for primary education came in the form of school meals and health care.

[Table 4.] Public Expenditure on Education by Various Concertacion Administrations

Public Expenditure on Education by Various Concertacion Administrations

In terms of housing, the government continued the practices of the junta by allowing private sector participation in the construction of new homes but increased public spending on housing by 50%. The government also changed the eligibility requirements for public housing programs to benefit lowincome families and provided subsidies to poor neighborhoods to fund utilities. And while the government maintained the structure of privatized heath care, it increased funding for the public health-care portions of the system that largely served the poor, especially primary care services. The government increased the salaries of health-care workers in the public sector and gave more authority to local and regional governments over the distribution of equipment and health-care resources and provisions.40)

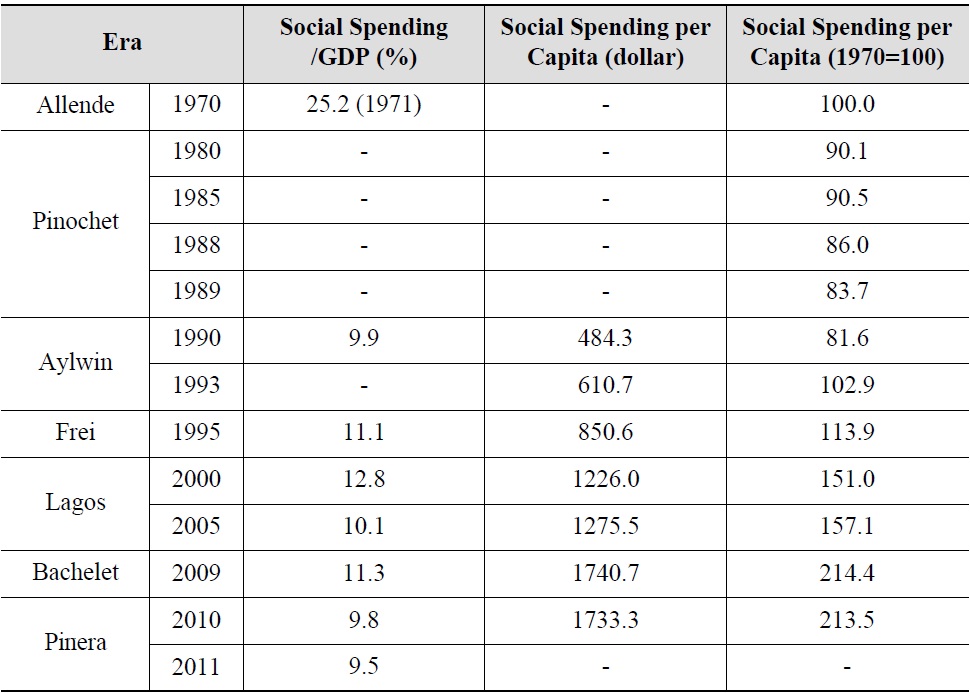

The privatized structure of Chile’s pension system was maintained by various Concertación administrations. The Concertación regimes, however, focused pension policies on improving the value of pensions. The Aylwin government increased the minimum pension that was paid of what remained of the state-run

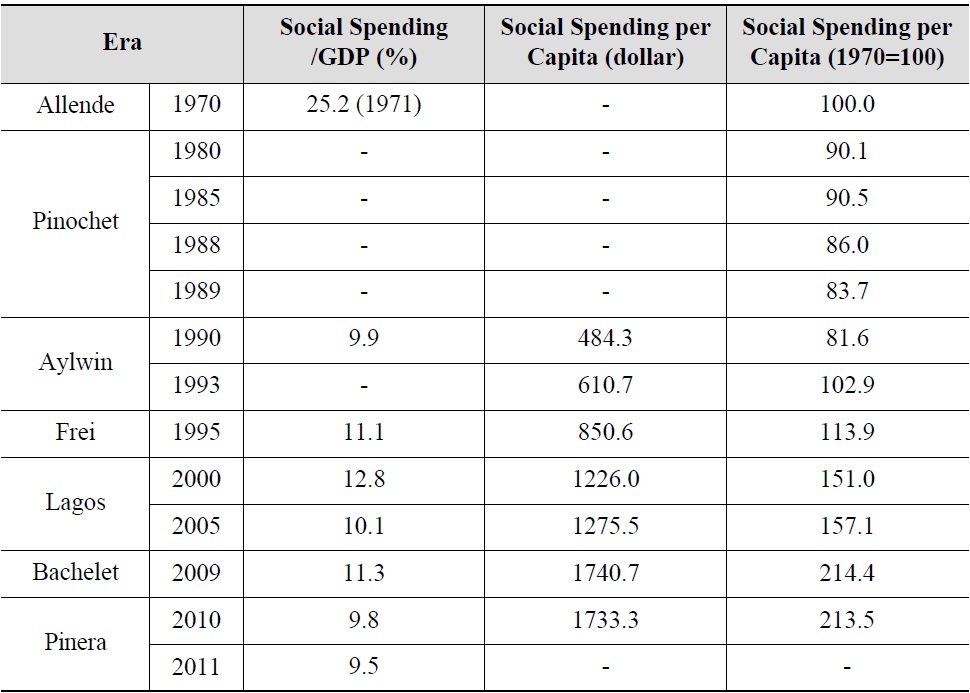

[Table 5.] The Transformation of Welfare Expenditures

The Transformation of Welfare Expenditures

In 2006, the Concertación government led by Michelle Bachelet moved to reform the private pension system to address the problems of coverage and the low participation among low income and self-employed members of the labor force. Referred to as the “reform of the reform” became law in 2008 and sought to strengthen Chile’s private pension system. The latest reforms created a new and more generous noncontributory “solidarity pension” that replaces both the means-tested PASIS benefit and the minimum pension guarantee that was established by the military junta. In 2012 when the reform was fully phased in, elders with family incomes of less than 60% of the national average are eligible for a full solidarity pension provided that they have no contributory pension benefit. Under the pension system that was created by the junta, low-income workers had little incentive to contribute once they qualified for the minimum pension guarantee. Under the new system, every additional income that is contributed to the personal accounts will earn an extra return.

The pension reform includes other measures that are designed to increase participation in the system. The reforms made participation by the selfemployed mandatory. This requirement will be phased in over a seven-year period. The reforms also seek to boost the participation of young low-income workers by paying subsidies to their employers who offer them formal-sector jobs. The personal retirement accounts for women will also be supplemented to compensate for time spent as noncontributors, while providing child care at home. In addition, the new reforms include measures that will reduce the administrative fees that are charged by pension fund managers plus measures that will improve competition among private Pension Fund Managing Corporations, often referred to as

In terms of health-care policies, the Aylwin government increased the resources to improve infrastructure and the equipment for public hospitals. The government also established new health-care policies modifying the existing policies for females and seniors. The Frei government enacted several measures to expand the coverage of medical service. A minimum coverage for preexisting conditions was established, excessive contributions of the insured were devolved to them, and some restrictions in coverage were alleviated.

36)Claudio Bravo-Ortega, Tradeliberalization in Chile: A Historical Perspective (Santiago, Chile: Universidad de Chile, Department of Economics, 2006). 37)Central Bank of Chile, “Indice Real ce Remuneraciones por Hora” (2004), available at

Ⅶ. Political Factors of Welfare Expansion under the Concertacion Governments

The basic characteristics of Chilean welfare state under the new democratic left were not quite different from those of the military government in that the welfare regime operated based on private market forces. However, economic globalization’s effect on the size of the state welfare was conditional on the nature of the domestic political environment. The nature of the Chilean political regime heavily conditioned the relationship between the openness of national economies and the size of the public sector’s welfare spending. Political regime type determines the political environment that shapes the incentives of government officials who make welfare policies. Democratic governments relative to authoritarian regimes are more likely to use welfare spending to compensate the losers of economic globalization to secure the support from the public. Since policymakers in democracies are subject to pressures from elections and interest groups, they are more likely to allocate a larger portion of their budgets for social welfare spending than those in authoritarian regimes.

In the face of the national crisis of developmentalism in early 1970s, the Pinochet regime pursued a minimalist state submitting to the market forces as a development strategy. Through this neoliberal strategy where the state subordinated to the abstract and seemingly neutral market forces, the Pinochet government tried to depoliticize the country and to some degree was successful. This “creative destruction” of the politics replaced the existing politicalized structure of social institutions with new laissez-faire economic system and repressive state.44) However, by the late 1980s, this repressive regime triggered vigorous demonstrations by the people. Finally, the Concertación’s activities brought the politics back into the state in 1988 and the presidential election was resurrected in 1989. This re-democratized Chilean political system increasingly required the political parties to pay more attention to developing policies to secure public support.

Political democratic theories emphasize the effect that political competition among political parties has on government welfare policies.45) Political competition refers to the intensity of elections which is often measured as the strength of opposition parties. When the electoral competition is intense, in order to boost political support political parties will be pressured to be engaged in social welfare reforms that they would otherwise ignore. Given the clientelistic nature of competitive electoral politics in many countries, political parties are likely to propose generous welfare benefits in order to secure votes. As the global economic integration of national economies increases, the clientelistic nature of competitive electoral politics is also expected to increase since parties increasingly seek to provide welfare benefits for constituent voting districts adversely affected by economic globalization.46)

Different from the former authoritarian regime, the Concertación had to be elected through political competition. In both plebiscite and the presidential election in 1988 and 1989, the margins of voting were just around 9%. In addition, even after the regime transition, the Concertación government was still suffering from the unbalanced political environment. According to the political pact with the rightists, which guaranteed designated Senate seats by Pinochet and Pinochet’s position as the commander of the Chilean military, the majority of the Senate was assumed by the anti-Concertación parties regardless of the electoral result. The binomial electoral system as well as non-elected senators also reinforced the power of the right in the parliament until the end of the Lagos government. The fact that the reform of social policies under Bachelet government—without designated senators—was much more progressive than those under the other Concertación governments reassures this argument.

These inferior conditions exerted the Concertación government harsher electoral pressure entailing the motivation to pledge more generous public policies to overcome the situation by securing public support. The new democratic Concertación governments strategically provided welfare compensation to build domestic political coalitions with the working class that support the new political regime, while keeping an open economy. Upon its inauguration in 1990, the Concertación government pledged ‘growth with equity,’ which entailed diverse social policies such as reform of labor law, revision of tax policies, increase of social spending, and installation of new social programs.

The nature of partisan politics also conditions the impact of global economic integration on governments’ welfare expenditures. Social democratic corporatist theories focus on the power of the political left; namely, leftist parties in shaping the welfare policies of the state.47) Leftist parties are known to focus more on economic (re)distribution than economic growth because they are supported by working classes. The core theoretical proposition of this perspective is that the political orientation of leftist parties and their supporters affects the ways in which the governments respond to economic globalization. The effect of global economic integration on states’ welfare spending is conditional on the nature of party politics. Governments led by left or centrist political parties (labor, social democratic, or Christian democratic parties) are more likely to support robust welfare policies than governments led by parties to the political right to compensate the losers of the economic globalization.48) Cynthia Kite argues that in countries where social democratic parties are strong the public is less tolerant of economic inequality and holds government accountable for providing welfare benefits.49)

The ruling center-leftist Concertación coalition effectively expanded the Chilean welfare expenditures to the level of quasi-comprehensive system (see Table 6). For fairer distribution of the economic growth, Aylwin government increased the value-added tax (VAT) from 16% to 18% and the corporate tax rate from 10% to 15%. The government also increased some income taxes. The attempt to increase taxes to finance social policies like Chile Solidario was reinforced under the Socialist presidents. Lagos increased corporate tax to 17% and VAT to 19%. President Bachelet was able to extend additional support to Chile Solidario with these increased taxes. However, the two Christian Democratic governments could not achieve any significant structural reform of social system, while they were successful in expanding social spending notably. The attempt to reform the legal structure of the welfare state was conspicuous under the Bachelet government. Furthermore, as seen in the Table 6, even under the Concertación governments, the leftist Lagos and Bachelet governments spent more money for social policies than the centrists Aylwin and Fei. This argument is corroborated by the fact that the proportion of social spending out of GDP decreased below 9% again under the rightist Pinera government.

[Table 6.] Government Social Spending under Concertacion (% GDP)

Government Social Spending under Concertacion (% GDP)

The growth of labor power also affected this expansionary reform of welfare promoting close collaboration between the Concertación government and labor. Different from the former military regime, the leftist government tried to incorporate labor in the decision-making processes both to strengthen political alliance with labor and secure majority votes in the election. Even from his campaign, Aylwin encouraged the political participation of labor with the catchphrase ‘recovery of trade union rights’. After inauguration, the Aylwin government coordinated social policies with labor through the tripartite commission—“Framework Accord” between the government, labor, and business associations—the Confederation of Production and Commerce.50)

Under this foundation of labor policy, several legislative reforms—regulations governing dismissals, collective bargaining, union confederations, and individual contracts—strengthened the political influence of labor. Employment protection was enhanced and the role of labor unions in the collective bargaining process increased. This labor reform recovered the definition of dismissals with ‘economic cause’ abolishing the politically motivated causes. The legal maximum severance package was raised from five to eleven months’ wages, and the responsibility to provide legal proof of ‘economic cause’ was attributed to employers. Moreover, all employees with more than six years tenure could transfer their program from the job security protection to an ‘unemployment fund’.51)

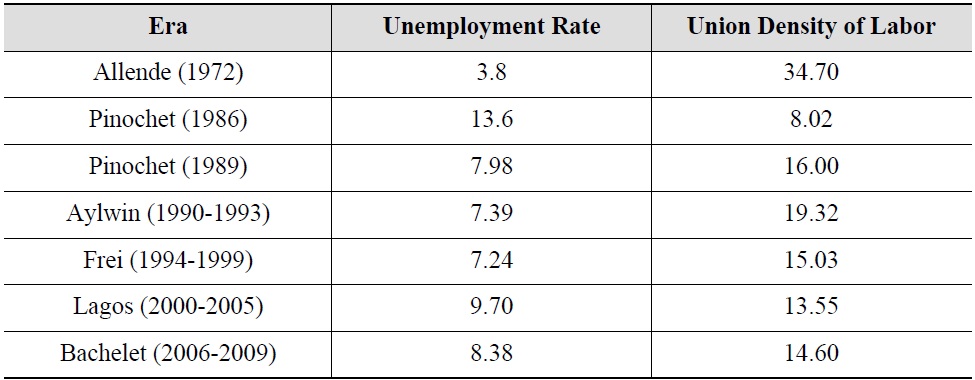

Following up on the Framework Accords, in 1991 people were allowed to organize labor confederations—a practice which had been banned under the military regime. In addition, the prevention of negotiations above the company level, or the prevention of collective bargaining over certain categories of dispute was abolished. Union federations were empowered to negotiate at the industry level as long as they represented a majority of the workers engaged. By the reform, the 60 days’ rule for the legal strike, which was abused to dismiss striking employees without severance pay, was eliminated. This trend of labor legislation reform was reinforced by the election of Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei to the presidency in 1994 when labor unions for public sector workers were legalized.52) Concertación government’s intention to enhance individual labor rights was expressed in the shape of increase of social benefits and pension programs, and continual efforts to negotiate a labor legislation reform in Congress during the period 1995-1998. A number of new laws and decrees with international standard were enacted. As a result, union membership drastically increased under the Concertación government (see Table 7).

[Table 7.] Labor Conditions in Chile (%)

Labor Conditions in Chile (%)

Faced with the authoritarian alliance within the state apparatus and the neoliberal economic system where the power of capital was maximized, the Concertación governments strategically adopted market-oriented economy to minimize the resistance of authoritarian political forces. This market-oriented economic system operated as a hurdle to transforming the welfare regime. Since state-led welfare system like the one under the Allende government could not be in harmony with the liberal market economy, the Concertación could not help keeping the liberal welfare system which was developed under the Pinochet government. However, at the same time, even though it was not strong enough to disrupt the neoliberal trajectory, the growth of labor operated as a pressure for the Concertación to strengthen the welfare state. Under this political dilemma, the Concertación alleviated the tension by expanding the size of the welfare expenditures, while keeping the existing liberal welfare regime. Upon his inauguration, Aylwin proclaimed the new government would succeed a market-based economic growth model, but one with fairer distribution of the economic fruit.

As such, resurrection of democratic rule increased the political influence of labor by having the collective bargaining system work more effectively. The number of strikes increased significantly compared with its frequency during the late military rule. After about ten years of transformation of the welfare state by the democratic center-leftist governments, the total poverty declined from 38% to 20% in 2000. According to

44)Marcus Taylor, “From National Development to ‘Growth with Equity’: Nation-building in Chile, 1950-2000,” Third World Quarterly 27-1 (2006), p. 70. 45)Alexander M. Hicks and Duane H. Swank, op. cit.; Cynthia Kite, “The Stability of the Globalized Welfare State,” in B. Sodersten (ed.), Globalization and the Welfare State (New York: Palgrave, 2004), pp. 213-238. 46)Paul Cammack, David Pool, and William Tordoff, Third World Politics: A Comparative Introduction (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988). 47)Alexander M. Hicks and Duane H. Swank, op. cit.; Peter Katzenstein, Small States in World Markets: Industrial Policy in Europe (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1985); Cynthia Kite, op. cit. 48)Evelyne Huber and John D. Stephens, Development and Crisis of the Welfare State: Parties and Policies in Global Markets (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001); John D. Stephens, “Economic Internationalization and Domestic Compensation: Northern Europe in Comparative Politics,” in Miguel Glatzer and Dietrich Rueschemeyer (eds.), Globalization and the Future of the Welfare State (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005). 49)Cynthia Kite, op. cit. 50)Paul G. Buchanan, “Preauthoritarian Institutions and Postauthoritarian Outcomes: Labor Politics in Chile and Uruguay,” Latin American Politics and Society 50-1 (2008), pp. 59-89. 51)Sebastian Edwards and Alejandra C. Edwards, “Economic Reforms and Labor Markets: Policy Issues and Lessons from Chile,” Economic Policy 15-2 (2000), pp. 181-230. 52)Sebastian Edwards and Alejandra C. Edwards, op. cit.; Paul G. Buchanan, op. cit. 53)J. Schatan, “Poverty and Inequality in Chile: Offspring of 25 Years of Neoliberalism,” Development and Society 30-2 (2001), pp. 57-77. 54)R. Soto and A. Torche, “Spatial Inequality, Migration and Economic Growth in Chile,” Cuadernos de Economlá 41 (2004), pp. 401-424.

Ⅷ. Future Challenges of the Welfare State

The dynamics of Chile’s welfare state can be explained with the interaction effect between the variation of economic globalization and the variation in the nature of its domestic political system. Chilean welfare state was transformed from a system with comprehensive benefits into one where benefits were significantly limited as neoliberal open economy was established by the military junta. Welfare policy under economic globalization has recently evolved into a quasi-comprehensive system by the Concertación government. These compensation policies by the Concertación government have considerably improved Chilean social dislocations. However, problems still exist.

According to the official data, the poverty rate in Chile would have declined substantially since 1990, owing to the very high economic growth rates. However, according to preliminary figures, poverty and indigence problems have not been substantially solved due in part to the increase in unemployment caused by the worldwide economic downturn. The socioeconomic inequality in Chile is one of the worst in Latin America. According to the World Bank, Chile’s Gini Coefficient in 2009 was 52, which was the thirteenth highest number among the 133 surveyed countries. In 1996 the average income of about half a million people of the top 5% was almost 100 times larger than the average of the poorest 10 million people. Furthermore, there is a clear proclivity that the correlation between overall economic development and the job creation is significantly diminishing, having reached a point where the elasticity GDP/employment is collapsing to zero.55)

In addition, there is tension between the Concertación government’s social welfare initiatives and its commitment to deepen Chile’s integration into the global economy. This tension will become more pronounced as Chile’s aging population increasingly demand greater outlays in social assistance. Furthermore, since Chile’s economy is deeply integrated into the global market, price fluctuations for copper and a prolonged recession in global capital markets could undermine the financial viability of public expenditures as well as threaten pension funds that are increasingly invested in overseas capital markets.56)

55)J. Schatan, op. cit. 56)Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, The Chilean Pension System (Paris, France: OECD, 1998).