The Bem Sex-Role Inventory (BSRI) is one of the most investigated psychometric constructs and a focus of evaluation for measuring individuals’ gender role orientation in terms of masculinity, femininity, androgyny, and undifferentiated. However, many studies have examined the BSRI with convenient samples drawn from university campuses. Moreover, the link regarding the BSRI’s cross-cultural applicability is weak (Peng, 2006, p. 843), which reduce the confidence in its validity. To partly address these two issues, this paper examines whether the BSRI is applicable to Uyghur Muslims in China. Uyghurs are chosen partly because of data availability. Equally important, the BSRI was first developed with data from the US. A study of Uyghur Muslims can test its cross-cultural applicability. A Uyghur sample is interesting because of the Muslim insistence on gender stereotypic traits (Zang, 2011).

This paper asks: how similar are Uyghur men’s ratings to the Uyghur women’s ratings for masculinity and femininity? What are the most important traits for masculinity or femininity according to Uyghurs? Will the BSRI be valid when tested with a sample drawn from the general population? Data are drawn from a survey on Uyghurs (

Sandra Bem (1979, p. 1048) developed the BSRI to assess the extent to which cultural definitions of desirable female and male attributes were reflected in an individual’s self-description. Prior to her study, masculinity and femininity were thought to constitute a single bipolar dimension. Bem treated the two dimensions as separate and orthogonal (Auster & Ohm, 2000). The original BSRI consisted of 60 items: 20 stereotypically masculine (M), 20 stereotypically feminine (F), and 20 neutral filler items. The scale reliability coefficients reported in the BSRI manual range from 0.75 to 0.90 (Bem, 1974, p. 157; Bem, 1979, pp. 1949-1950; Bem, 1981, pp. 19-20)

The original BSRI was soon challenged in terms of its theoretical basis, item selection, dimensionality, etc. It was argued that the BSRI was atheoretical, that

Empirical studies of the BSRI have so far produced mixed results. Twenge’s (1997) meta-analysis of 63 studies showed that women’s self-ratings on masculinity had been increasing steadily and gender differences in self-ratings on the masculinity dimension had been decreasing over time. Auster and Ohm (2000, p. 522) found that 18 of 20 feminine traits still qualified as feminine, but only 8 of 20 masculine traits qualified as masculine. Hoffman and Borders (2001) asked whether gender schema theory that Bem had used to develop BSRI was still relevant today given rapid changes in social norms and women’s status in society since the 1970s.

In contrast, Walkup and Abbott (1978, p. 63) validated the 18 of the 20 masculine items and 19 of the feminine items on the original BSRI. Using 3,000 patrons of the two shopping malls in Chicago, Harris (1994) found that 19 masculine traits (the trait “masculine” was excluded) and 16 of the 19 feminine traits (the trait “feminine” was excluded) met Bem’s original criteria for inclusion. Holt and Ellis (1998) replicated Bem’s procedure and found minor discrepancies from the original scales. The reliability coefficients for the two scales were both over 0.90. Özkan and Lajunen (2005, p. 104) claimed that gender stereotypic traits were universal and that the BSRI was still valid although traditional M and F perceptions might be weakening.

Studies of Gender Stereotypic Traits among Han Chinese

Most of the BSRI studies have been based on samples from North America. Is the BSRI applicable to a non-Western cultural setting such as China? So far, there are a few BSRI studies using Han Chinese as research participants. Wang and Creedon (1989) found that Chinese men rated themselves significantly higher than Chinese women on the M scale, and women rated themselves significantly higher than men on the F scale. This pattern is consistent with the results reported in Bem for her US samples. Zhang, Norvilitis, and Jin (2001) found that for the M scale, the Chinese data yielded six factors, and the US data yielded four factors; for the F scale, six and five factors were yielded for the Chinese and the US samples respectively. On the 20 M items, the US men rated themselves higher than the US women did on 15 items, while the Chinese men rated higher than the Chinese women did on 17 items. With regard to the 20 F items, the Chinese women rated themselves higher than the men did on 12 items whereas the US women rated themselves higher than the men did on 17 items.

There are a few studies of Han Chinese outside mainland China. Hong and Rust (1989) sampled 100 Chinese in England and used the short form of the BSRI. They reported a correlation of only 0.07 between masculine and feminine scales, supporting Bem’s two-dimension claim. Lau (1989; also Lau & Wong, 1992) studied students in Hong Kong and found that the Cronbach’s alphas for the M and F scales were 0.80-0.87 and 0.70-0.75 respectively. Lau claimed that the BSRI was meaningful in Chinese culture and had similar psychological properties as it did in the US. Peng (2006, pp. 847-848, 850) found that in Taiwan, male respondents scored higher than female respondents on the 10 M items, which supported Bem. However, they also scored significantly higher than their female counterparts on the five F items: loves children, eager to soothe hurt feelings, tender, sensitive to the needs of others, and gentle. No significant differences were found between men and women on the remaining items. Peng (2006, p. 845; also Zhang, Norvilitis, & Jin, 2001, p. 249) concluded that the reliability of the M and F scales was generally acceptable in the Chinese context.

The Perception of Masculinity and Femininity among Muslims

By no means does the above discussion on Han Chinese imply that the BSRI can apply to Uyghur Muslims. Unlike Han Chinese, Uyghurs are ethnically Turkic and Muslims. Bem (1979, p. 1048) stressed the role of culture in defining desirable female and male attributes. Gender stereotypes may vary among different cultures and ethnic groups (Özkan & Lajunen, 2005, pp. 103-104). For example, some Muslim communities have maintained restrictive attitudes toward Muslim women. Hindu nationalists have described Muslim men as militant and sexually predatory (Jeffery & Jeffery, 2002, p. 1806). Therefore, a review of the studies of Muslims is useful and necessary for the Ürümchi study.

Only a few studies have used a Muslim sample or a sample from a Muslim majority country. Damji and Lee (1995, pp. 220-221) recruited 46 male and 35 female Muslims in the Ismaili mosque in Ottawa, Canada, and found that the Muslim women scored significantly higher on the femininity scale than did the Muslim men. But there were no significant differences between the genders with regard to the masculinity scale. The Muslim men scored higher on the femininity scale than did the 476 male Stanford University students in the Bem original study. There were no significant differences on the BSRI masculinity and femininity scales between the Ismaili Muslim sample and a group of sophomore students they sampled from the University of Alberta in Canada.

Abu-Ali and Reisen (1999, pp. 185, 191) studied 96 Muslim adolescent girls attending an Islamic high school in the US and found that these young women had comparable femininity scores, but higher masculinity scores than the US college women in Bem’s original samples. The masculinity score was below that for Bem’s male samples. The scores on the femininity scale were significantly higher than those of the masculinity scale.

Using 138 university students in Ankara, Turkey (presumably the majority of them were Muslims), Sevim (2006) found that femininity was associated with warmth, expressiveness and nurturance. Women seemed more concerned than men about relationships and about the feelings and ideas of others. Women were more empathic and more nurturing than men. Most of the participants who had feminine traits were female. Men were more traditionalist than women were with respect to these gender role attitudes.

Finally, Özkan and Lajunen (2005, pp. 103-110) conducted a survey among 280 men and 256 women from an elite university in Turkey and found that men scored lower on masculinity than on femininity. Women scored higher on femininity than on masculinity. Comparisons between men and women showed a major difference on the femininity scale of the BSRI but not on the masculinity scale. Both men and women scored higher on femininity than on masculinity. Women scored higher on femininity than men, whereas no differences between the sexes were found on masculinity scores. The findings supported the original BSRI masculinity-femininity structure.

Despite the above studies, the validity and applicability of the BSRI in different cultural contexts is still unclear because of the mixed findings and the convenient samples used by most studies of the BSRI. To contribute to this large literature, I draw data from a survey on Uyghur Muslims conducted in Ürümchi, capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, in 2007. It is necessary to point out that the Uyghurs in the city are not representative of Uyghurs in Xinjiang as the majority of them live in rural areas. However, an urban Uyghur sample can lead to some interesting findings about the effect of modernization on perceptions of masculinity and femininity.

Xinjiang is located in Northwest China and occupies one sixth of China’s territory. As noted, Uyghurs are a Turkic people and Sunni Muslims. They take Islamic foods, wear their costumes, and celebrate their own festivals. Their language, written in the Arabic script, belongs to the Turkic language. They are “one of the most nationalistic and least assimilated minorities in China” (Mamet, Jacobson, & Heaton, 2005, p. 191; also Dautcher, 1999, pp. 54-55, 337-339; Rudelson & Jankowiak, 2004, p. 311).

Uyghurs had lived in north-western Mongolia before they migrated enmasse to Xinjiang after the demise of the Uyghur Empire in 840. They practiced Manichaeanism, Nestorian Christianity, and shamanism before 932. Some Uyghurs became Buddhist; others were converted to Islam before the Mongol conquest around 1200 of the region known as Xinjiang today. The massive Uyghur conversion to Islam started after the Mongol conquest but was not completed until the mid-1400s. Some scholars claim that the Islamic conversion was basically achieved in the 1600s. Xinjiang became a province of the Qing Empire in 1884. After the establishment of the Republic of China (ROC) in 1911, it was ruled by Han warlords. The ROC managed to place Xinjiang under its direct control in 1944. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) took over Xinjiang in 1949.

When the CCP came to power in 1949, it strived for total power in an effort to transform China into a socialist country and to fully integrate Xinjiang into the PRC. The CCP regarded Islam as an alternative to political allegiance to the PRC state and made efforts to undermine the position of mosques and imams in Xinjiang. The CCP eliminated institutional Islam’s main source of revenues and has incorporated imams within the Beijing-based Chinese Islamic Association (Millward & Tursun, 2004, pp. 88-89). Religious suppression accumulated during the Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976. The government policies included the closing of rural bazaars, attacks on imams and mosques, forcible acculturation and assimilation, etc. (Fuller & Lipman, 2004, pp. 322, 326-328; also Rudelson & Jankowiak, 2004; Smith, 2000)

The political situation in Xinjiang changed in the 1980s. The CCP relaxed its grip on Islam due to its need to open China to the Muslim world for foreign trade and investment. It allowed greater autonomy and a relatively tolerant environment for ethnic and religious expressions in Xinjiang. This, together with events such as the formation of the five independent countries in Central Asia after 1991, has led to Islamic revival in Xinjiang. A large number of new mosques were constructed across the region between the 1980s and the 1990s (Smith, 2000, pp. 202, 208; also Mackerras, 2001; Rudelson & Jankowiak, 2004). In response, the CCP has reinforced its control over religious organizations and activities in the region since 1997. Yet the Islamic revival has ensured that “Muslim rituals influence all realms of Uyghur life” and “religious and cultural practices have become deeply intertwined” (Clark, 1999, p. 103; Fuller & Lipman, 2004, pp. 338, 341; Rudelson, 1997, pp. 48-49, 82-95).

Smith (2000, pp. 202, 208) found a reassertion of Uyghur ethnic identity in the forms of a re-traditionalisation process after the 1980s. Part of the retraditionalisation has focused on gender roles. I found during my fieldwork in Ürümchi that many Uyghurs supported gender equality in education and employment and disagreed that Islam suppressed women. At the same time, they insisted that the traditional gender roles were part of Uyghur culture and were consistent with the Islamic religion, and that Uyghur nationhood was based on good housewifery and Muslim motherhood. Uyghur parents wanted a daughter to be a good housewife after her marriage and expected a son to carry his family name to the next generation, contribute to the family’s welfare through financial and practical help, and take care of aging parents. These expectations guided Uyghur parents to train a child to fit his or her gender stereotype. Uyghur parents taught their sons to be independent and “act like a man”, whereas gentle and caring behaviour, obedience, and empathy were expected from their daughters, and this difference increased with the child’s age.

Gender role differentiation was observed in the division of labour between Uyghur men and Uyghur women in the family. Men were in charge of financial provision, physically heavy jobs and overall leadership in the family. Women were responsible for household tasks, childcare, elderly care, etc. It was considered as a shame if men do “women’s work”. If a man had to do household chores he preferred to do them when no outsiders were around (Rudelson, 1997). The division of labour was partly based on the assumption that men and women had different personality traits. Uyghur women were seen as being more dependent, more emotional, more submissive, more passive, more honest, more naïve, and weaker than Uyghur men, whereas Uyghur men were seen as being more independent, more aggressive, and more dominant than Uyghur women. Uyghur women could be “weak” and express their fragile or negative feelings, whereas men were expected to “be strong and tough” and to be self-sacrificing and able to maintain control under pressure. These gendered evaluations and expectations are more or less consistent with the masculine traits and feminine traits of the BSRI. It is likely that the data from the Uyghurs would support the validity and usefulness of the BSRI in the Ürümchi context.

However, this likelihood cannot be taken for granted. Since 1949, the Chinese government has carried out large scale modernization campaigns including education, industrialization, urbanization, etc. in Xinjiang. It has discouraged or even forbidden some Uyghur customary practices and promoted love and mutual companionship as major criteria in mate selection, creating the condition for gender egalitarianism to emerge in Xinjiang (Beller-Hann, 1998, 2004; Caprioni, 2008; Clark, 1999; Rudelson, 1997; Zang, 2008). Equally important, the Chinese government has promoted the idea that women “hold up half the sky” (i.e. women share equal social importance with men). It criticized patriarchal ideology and publicized gender equality values. It is important not to overstate the government’s achievements (Hershatter, 2007, pp. 5, 8, 60-64). Nevertheless, I observed in Ürümchi that many Uyghur women were employed. The changes in legal rights for women, expanded educational opportunities, increasing access to the internet, etc. have influenced the traditional structure of the gender roles. Uyghur women’s status in both society and the family has been greatly enhanced. In addition to these social and cultural changes, some of the working women have re-evaluated and showed masculine traits (e.g., assertiveness) in the workplace for career mobility or better working conditions including better wages. Finally, some Uyghur men in Ürümchi are well educated, support conjugality, and endorse gender egalitarianism (at least theoretically). Uyghur men and women may have already incorporated a great variety of masculine and feminine traits into their behavioural repertoire and may be more flexible in rating desirable traits from masculinity and femininity, thereby invalidating the BSRI in the Ürümchi context.

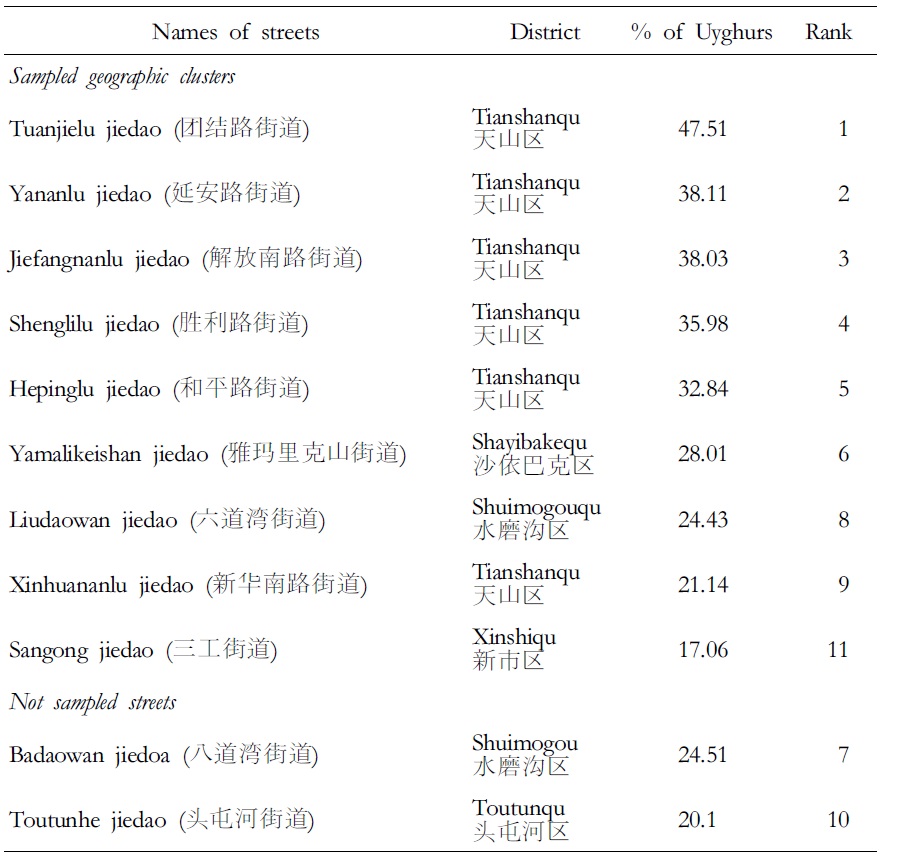

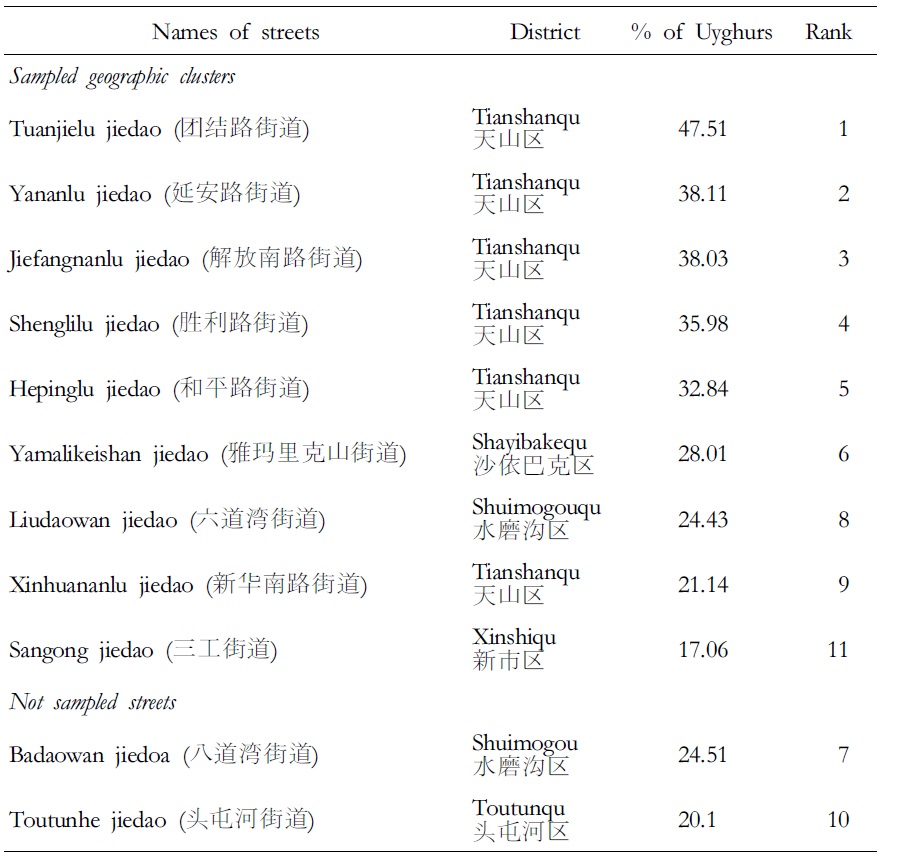

Thus, it is important to conduct empirical research to find out whether the BSRI is applicable to Uyghurs. I use data from a survey conducted in Ürümchi in 2007. Simple random sampling was not used in the survey: Uyghurs represented less than 10 percent of the total population in Ürümchi (Zang, 2011, p. 32). In addition, they were not evenly distributed in the city. Thus, my collaborators chose ten neighborhoods with the highest percentages of Uyghur households among their residents in Ürümchi as sampling clusters. However, Badaowan Street and Toutunhe Street, which reported the seventh and tenth highest percentages of Uyghur households in the city, declined to corporate with the local survey takers. Sangong Street, which was ranked the eleventh with 17.1 percent of Uyghur households among its residents, was used to make up the shortfall (See Table 1).

[Table 1] Sampled Urumchi Streets, 2007

Sampled Urumchi Streets, 2007

There was great variation in the percentages of Uyghur households (from 47.5 percent in Tuanjielu Street to 17.1 percent in Sangong Street) among the nine clusters. Thus, the probability proportional to size selection method was used so that each Uyghur household in the nine sampling clusters had the same chance of selection. A total of 1,394 Uyghur households were selected. Among them, 494 were not interviewed due to unavailability, refusals, or no access to gated residential buildings. The completion rate for the survey was 64.7 percent (

Following Choi, Fuqua, & Newman (2009), Özkan and Lajunen (2005, p. 105), and Peng (2006, p. 847), I use the Bem short version of femininity and masculinity scales. The neutral items were not included. The short version is used for greater levels of clarity and parsimony. It is conceptually sound, its internal consistency is reported as higher than that of the longer form, and the correlations between the long and short forms are impressively high (Choi, Fuqua, & Newman, 2009, pp. 698, 703-704; also Hoffman & Borders, 2001).

Zhang, Norvilitis, and Jin (2001) claim that “Cross-cultural studies on the BSRI generally suggested the existence of internal consistency and face validity of the scales in different cultures, but with removal of certain items from the original instrument” (p. 242). Local Han and Uyghur informants pointed out that many masculinity traits such as “assertive”, “dominant”, “forceful”, and “willing to take a stand” already measured the dimension of masculinity that the adjective “defends on own belief” did. They claimed that Uyghur manhood was partly measured by his ability to provide for his family. A man could not socially become an adult without financial independence. Thus, “defends on own belief” was replaced with “self-sufficient”. Indeed, some existing studies have shown that self sufficient is a key masculine trait (Auster & Ohm, 2000, p. 525; Blanchard-Fields, Suhrer-Roussel, & Hertzog, 1994, pp. 424, 435; also Choi, Fuqua, & Newman, 2008). As a result, masculinity is measured in this paper by ten items: aggressive, assertive, dominant, forceful, has leadership abilities, independent, strong personality, self-sufficient, willing to take a stand, and willing to take risks. Femininity is measured by ten items: affectionate, compassionate, eager to sooth hurt feelings, gentle, loves children, sympathetic, tender, sensitive to the needs of others, understanding, and warm (Peng, 2006, p. 846).

Following Bem (1981, p. 17), the Uyghur respondents were asked in the 2007 survey to rate the masculine and feminine items based on their judgements on how Uyghur culture evaluated each of these characteristics in a man/woman rather than their personal opinion of how desirable each of these characteristics was. In other words, they were asked to use the BSRI to judge what a Most Ideal Men and a Most Ideal Women were. Data analysis below uses the seven-point Likert scale so that 1 denotes “never or almost never true” and 7 denotes “always or almost always true.”

There are 416 men and 468 women in the Ürümchi sample. In order to be as consistent with Bem’s original study as possible, the Ürümchi sample is weighted to match her original sample, such that in data analyses there are half of the respondents (males) and half of the respondents (females) rating the desirability of traits “for a man” and the desirability of traits “for a woman.” By weighting the sample, I eliminate the possibility that the mean desirability ratings would be either significantly different from one another or not significant, because this sample size differs from the original sample used by Bem to develop the BSRI.

>

Mean Desirability Ratings of Masculinity and Femininity

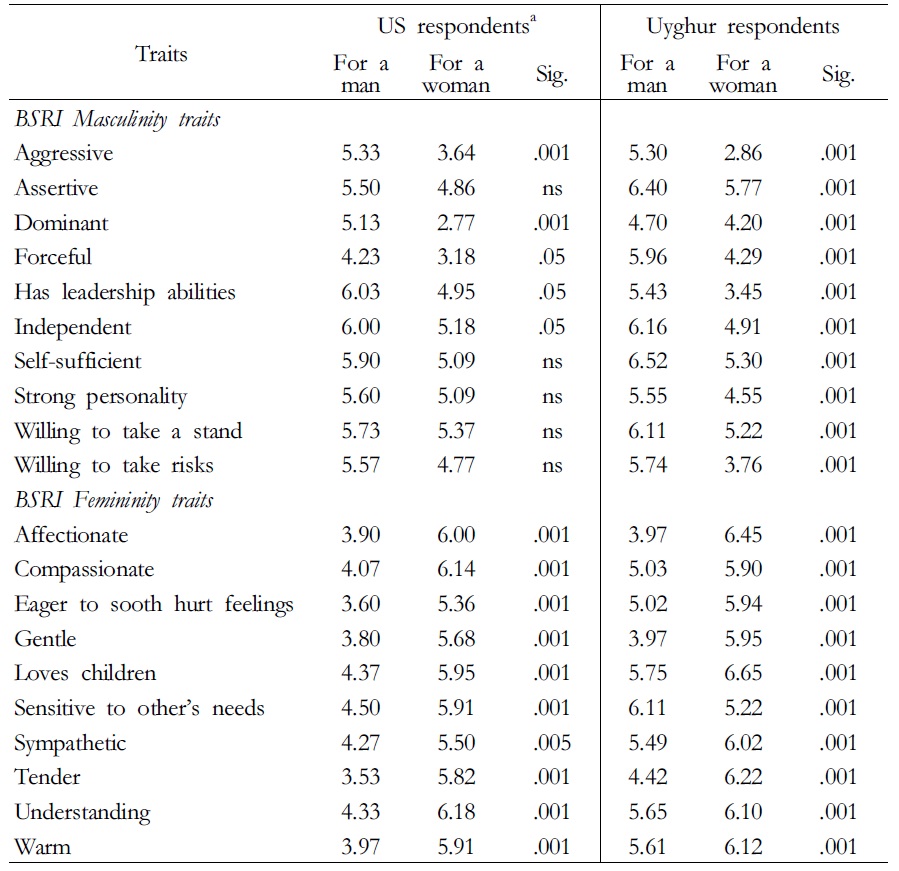

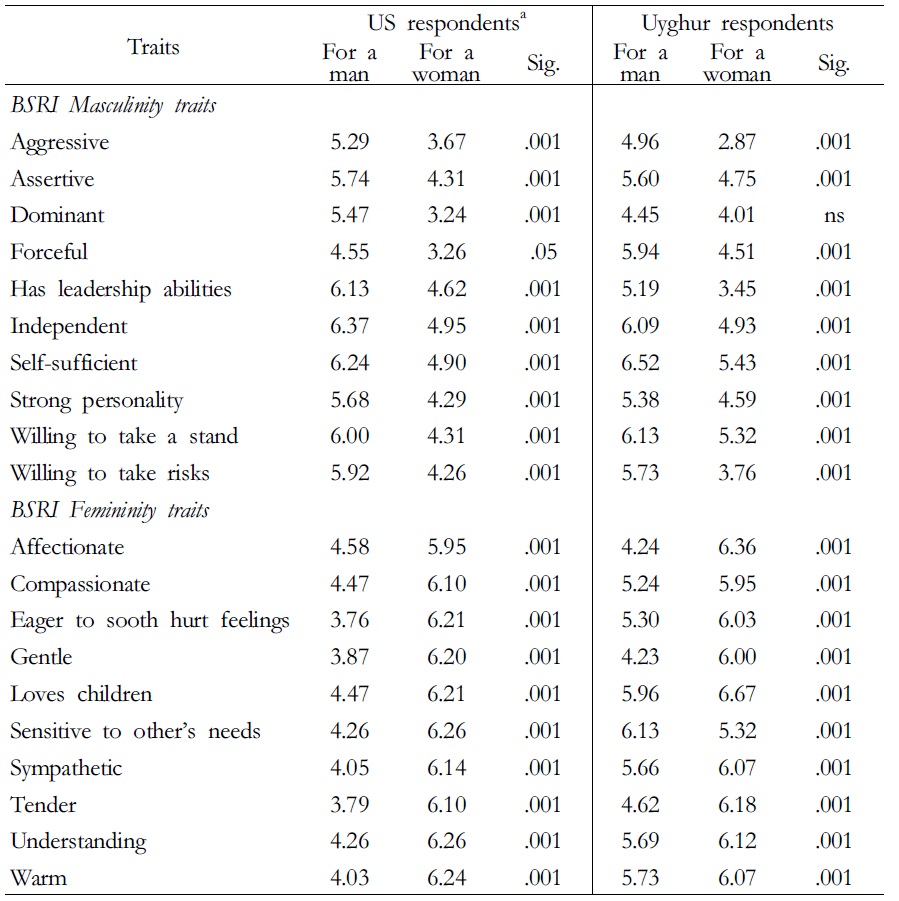

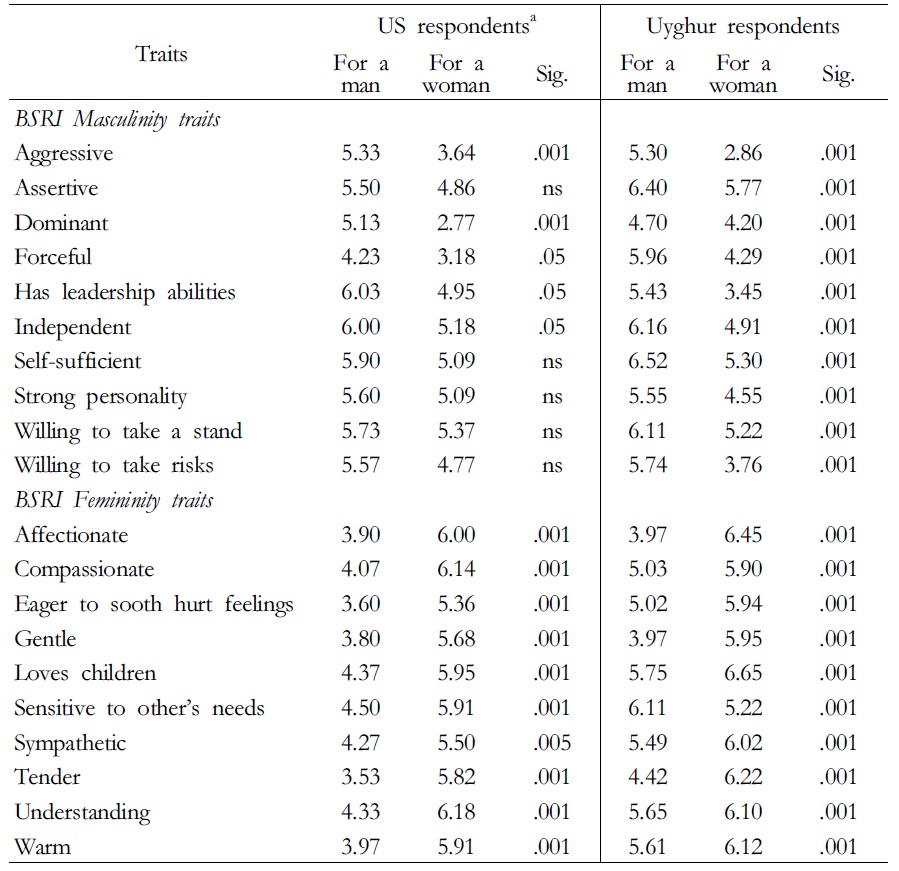

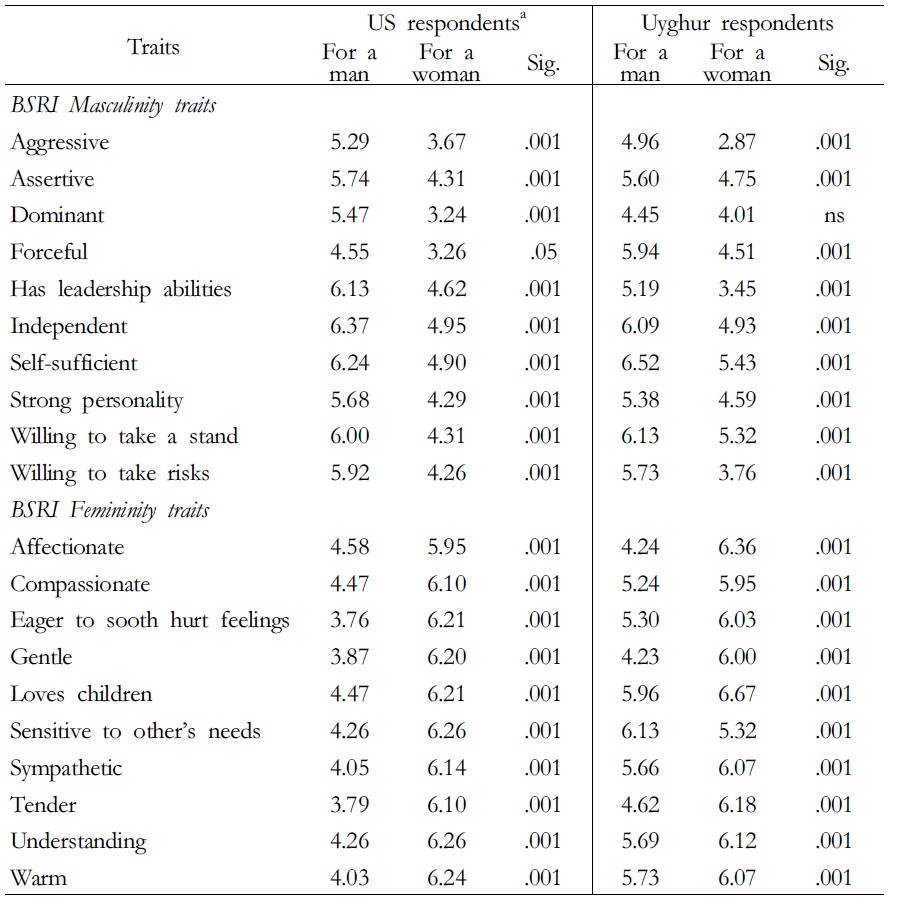

How do Uyghurs rate the masculine scale and the feminine scale of the BSRI? Tables 2 & 3 show the male and female respondents’ mean desirability ratings “for a man” and “for a woman” and the paired t test results. These findings can be used to examine whether the masculine and feminine traits which comprise the BSRI are valid in the Ürümchi context. Table 2 shows that the male respondents’ mean desirability ratings “for a man” and “for a woman” are significantly different for both the 10 masculine items (

[Table 2] Mean desirability ratings by male respondents

Mean desirability ratings by male respondents

[Table 3] Mean desirability ratings by female respondents

Mean desirability ratings by female respondents

A point of reference is essential for readers to understand Uyghur perceptions of masculinity and femininity well. Thus, I compare the mean desirability ratings by the Uyghur respondents with those by the US college students in Auster and Ohm’s sample (2000). Table 2 shows that the mean desirability ratings “for a man” and “for a woman” by the female college students in Auster and Ohm’s sample were significantly different for all 10 feminine traits, and the US male respondents’ mean desirability ratings “for a man” and “for a woman” were significantly different for the 10 feminine traits. The US female respondents’ mean desirability ratings for the 10 masculine traits were also significant. However, only 5 of the 10 masculine traits (aggressive, dominant, forceful, has leadership abilities, and independent) were rated by the US male respondents’ as significantly different. In other words, using Bem’s criteria, only these five traits would qualify as masculine. The BSRI was developed in the US, yet it seems to be more relevant in the Ürümchi context than in the US.

>

Similarities in Male/Female Respondents’ Ratings

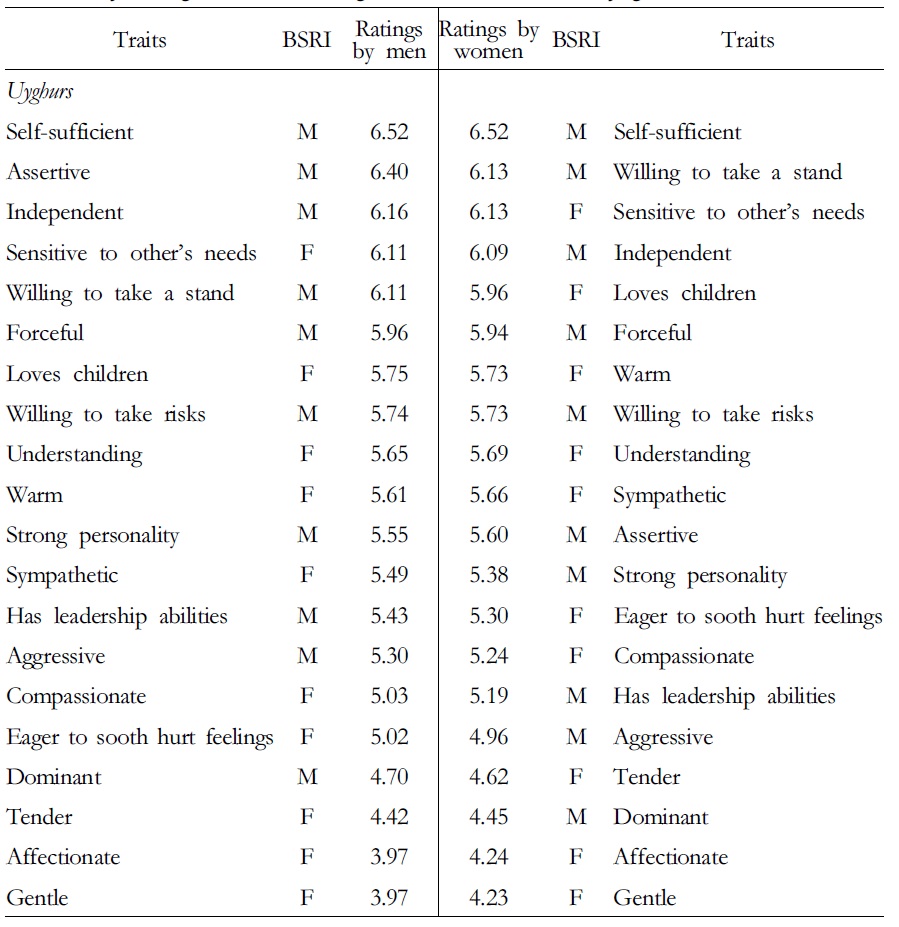

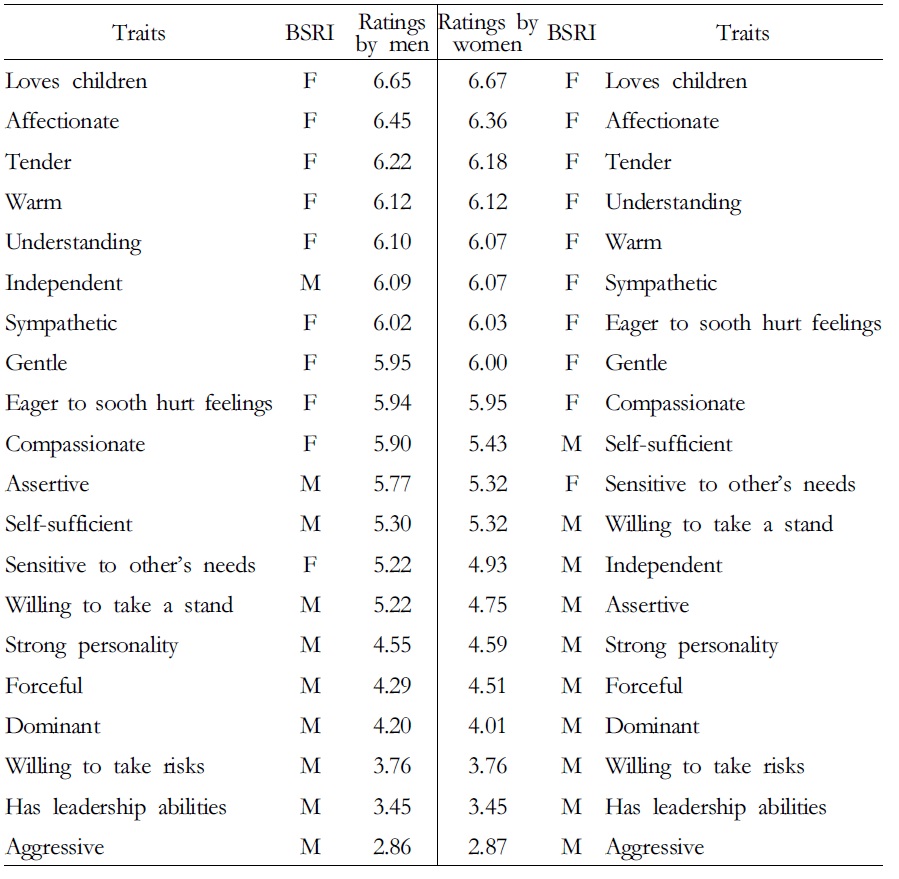

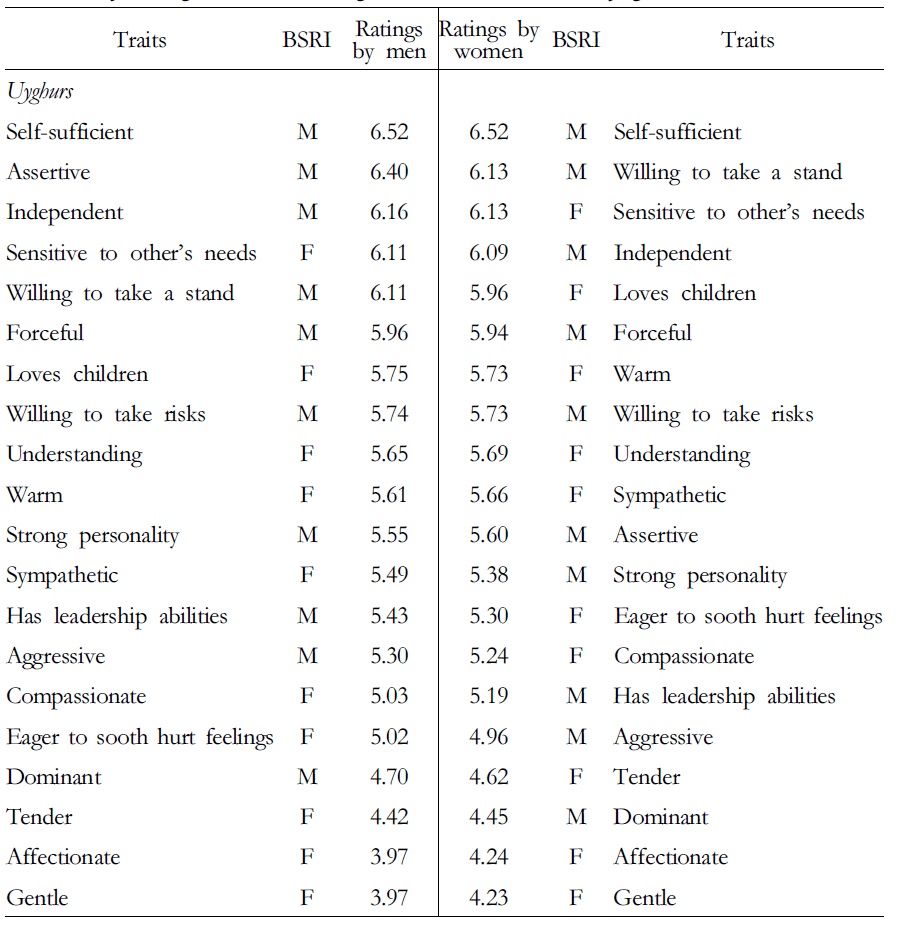

Are the Uyghur male respondents’ ratings different from the Uyghur female respondents’ ratings for masculinity and femininity respectively? Do the men and the women stress different masculine and feminine traits? Table 4 shows that the top ten masculine traits rated by the Uyghur men “for a man” include six masculine traits and four feminine traits. Among the top five traits, four are masculine (“self-sufficient”, “assertive”, “independent”, and “willing to take a stand”) and one is feminine trait (“sensitive to the needs of others”). The top ten masculine traits rated by the Uyghur women “for a man” include five masculine traits and five feminine traits. Among the top five traits, three are masculine (“self-sufficient”, “willing to take a stand”, and “independent”) and two are feminine (“sensitive to the needs of others” and “loves children”). Both the men and women rated “self-sufficient” as the most important masculine trait. Overall, there is a reasonable degree of similarity with regard to the highest rated five masculine items across the sexes. In contrast, both the men and women gave the lowest ratings to “dominant”, “tender”, “affectionate”, and “gentle” as they perceived these four items to be the least like what an ideal man should be.

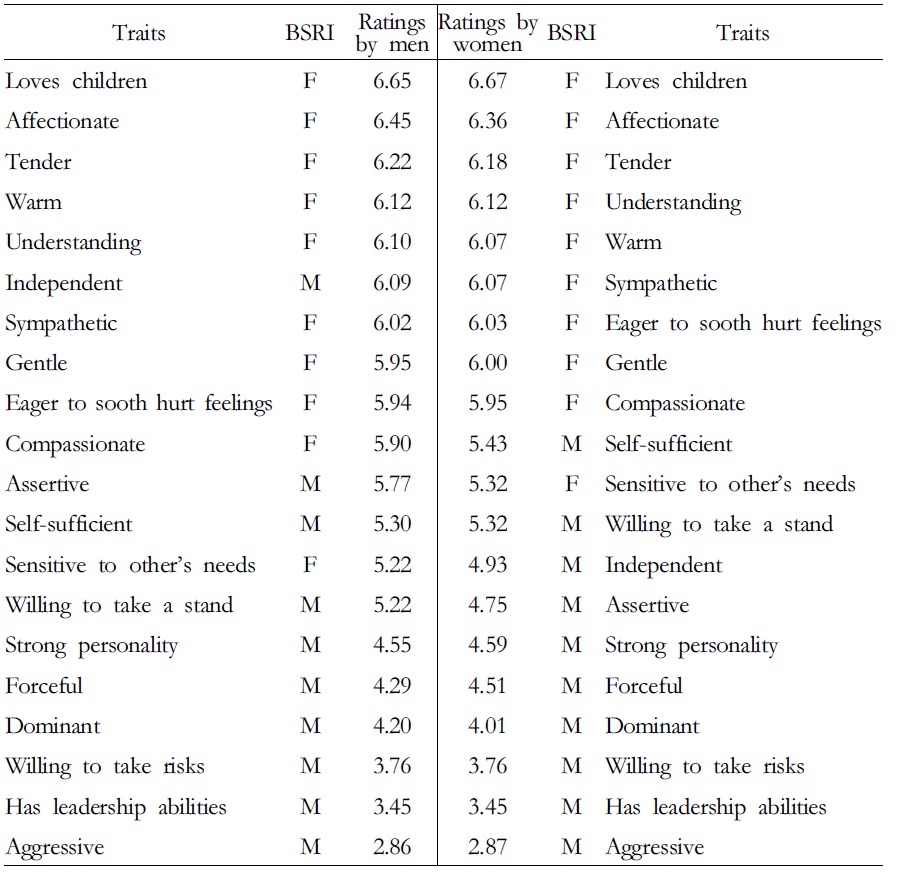

Table 5 shows that the top ten feminine traits as rated by men “for a woman” include nine feminine traits and one masculine trait. All of the top five traits are feminine traits. The top ten feminine traits as rated by women “for a woman” include nine feminine traits and one masculine trait. All of the top five traits are feminine traits. Overall, there is a good degree of similarity in rating the feminine scale by the Uyghur men and women, and the degree of similarity is higher than when they rated the masculine scale. In addition, the highest rated five feminine items across genders include “loves children”, “affectionate”, “tender”, “warm” and “understanding.” In other words, the Uyghur respondents, regardless of their gender, considered these five adjectives most appropriately described what an ideal woman should be. Similarly, both the men and women gave the lowest ratings to “forceful”, “dominant”, “willing to take risks”, “has leadership abilities”, and “aggressive”, as they perceived these five items to be the least like what an ideal woman should be.

[Table 4] Desirability ratings in descending order “For a man” by gender

Desirability ratings in descending order “For a man” by gender

[Table 5] Desirability ratings in descending order “For a woman” by gender

Desirability ratings in descending order “For a woman” by gender

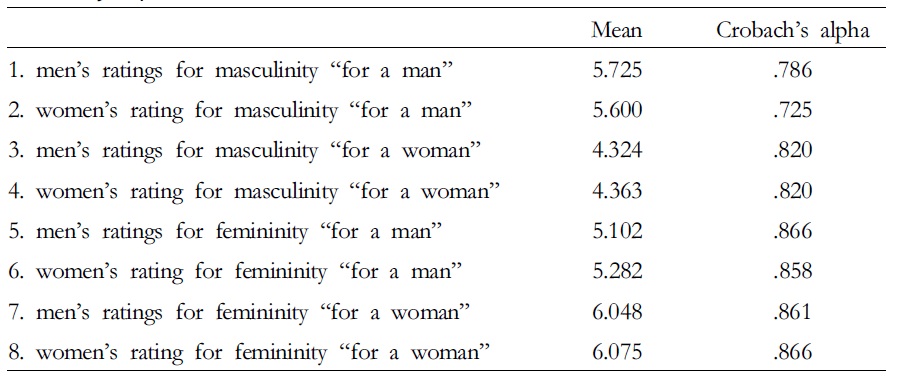

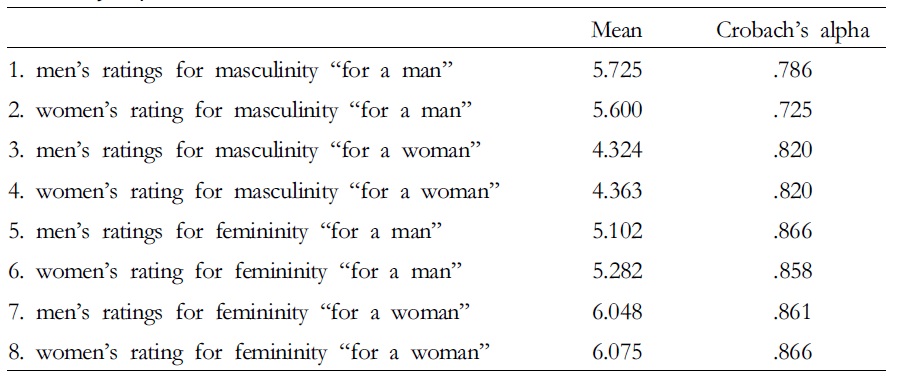

Table 6 shows that the mean desirability ratings of the masculine scale “for a man” by the male respondents’ is higher than those by the female respondents. The mean of the male respondents’ ratings for masculinity “for a man” is 5.725, as compared with 5.600 by the female respondents. The mean desirability ratings of the masculine scale “for a woman” by the male respondents did not exceed that by the female respondents. The mean of the male respondents’ ratings for the masculine scale “for a woman” is 4.324, as compared with 4.363 by the female respondents. The mean desirability ratings of the feminine scale “for a man” by the male respondents’ are lower than those by the female respondents. The mean of the male respondents’ ratings for femininity “for a man” is 5.102, as compared with 5.282 by the female respondents. The mean desirability ratings of the feminine scale “for a woman” by the male respondents’ is similar to that by the female respondents. The mean of the male respondents’ ratings for the feminine scale “for a woman” is 6.048, as compared with 6.075 by the female respondents.

Reliability alphas

In short, the Uyghur men score higher than the Uyghur women on masculine items and the Uyghur women score higher than the Uyghur men on feminine items. These patterns are consistent with the expectations from the BSRI (also see Blanchard-Fields, Suhrer-Roussel, & Hertzog, 1994, p. 433; Peng 2006, p. 847). The findings in Tables 2-6 thus suggest a good validity for the BSRI. In comparative perspective, these findings are more or less similar to those reported by Özkan and Lajunen (2005, p. 105). Finally, the Crobach’s alphas (α) shown in Table 6 show satisfactory internal consistency of the ratings reported in this paper.

Taken together, it can be seen that the Uyghur respondents of both genders congruently perceived some items as appropriate and others as less so in rating the masculine scale and the feminine scale of the BSRI. An important observation is that all of the lower rated masculine items in Table 4 are higher than or close to 4.0 on the 1 through 7 scale, which suggests that for both the male respondents and the female respondents, even the less appropriate adjectives are more or less true with regard to masculinity. However, the desirability ratings for “aggressive” (2.86 and 2.87), “has leadership abilities” (3.45 and 3.45), and “willing to take risks” (3.76 and 3.76) in Table 5 are lower than 4.0. This suggests the need to examine the construct validity of the short form of the BSRI through principal components analyses.

>

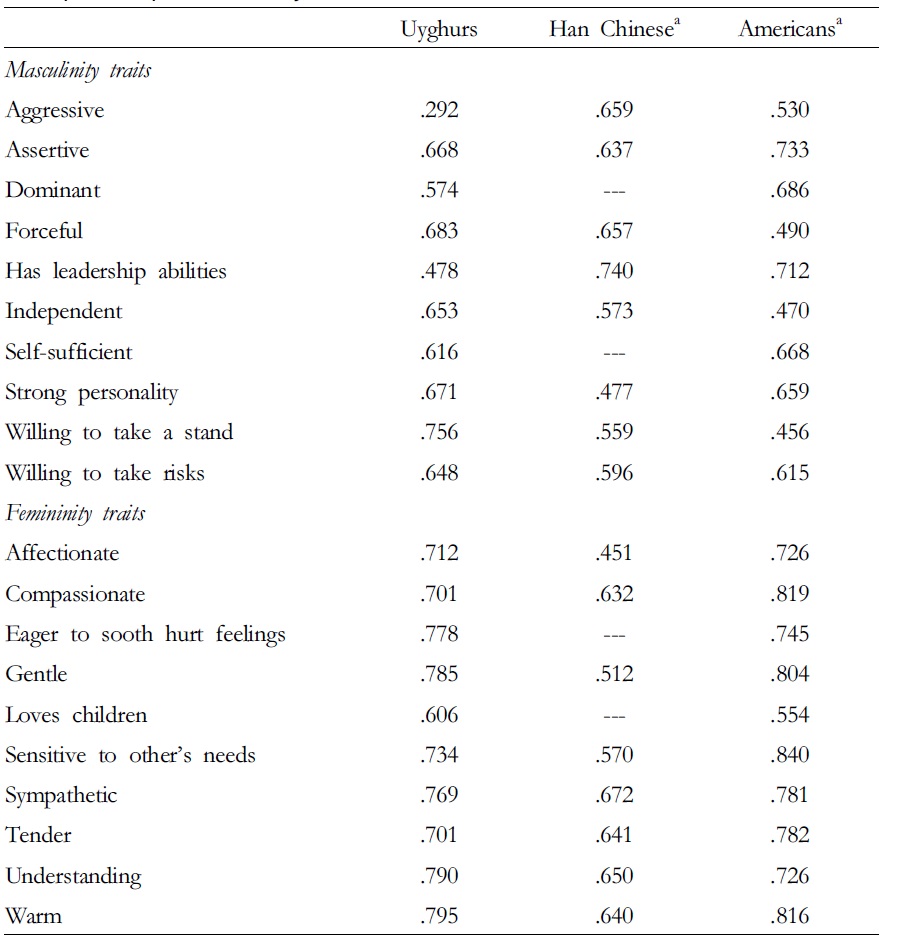

Principal Components Analyses

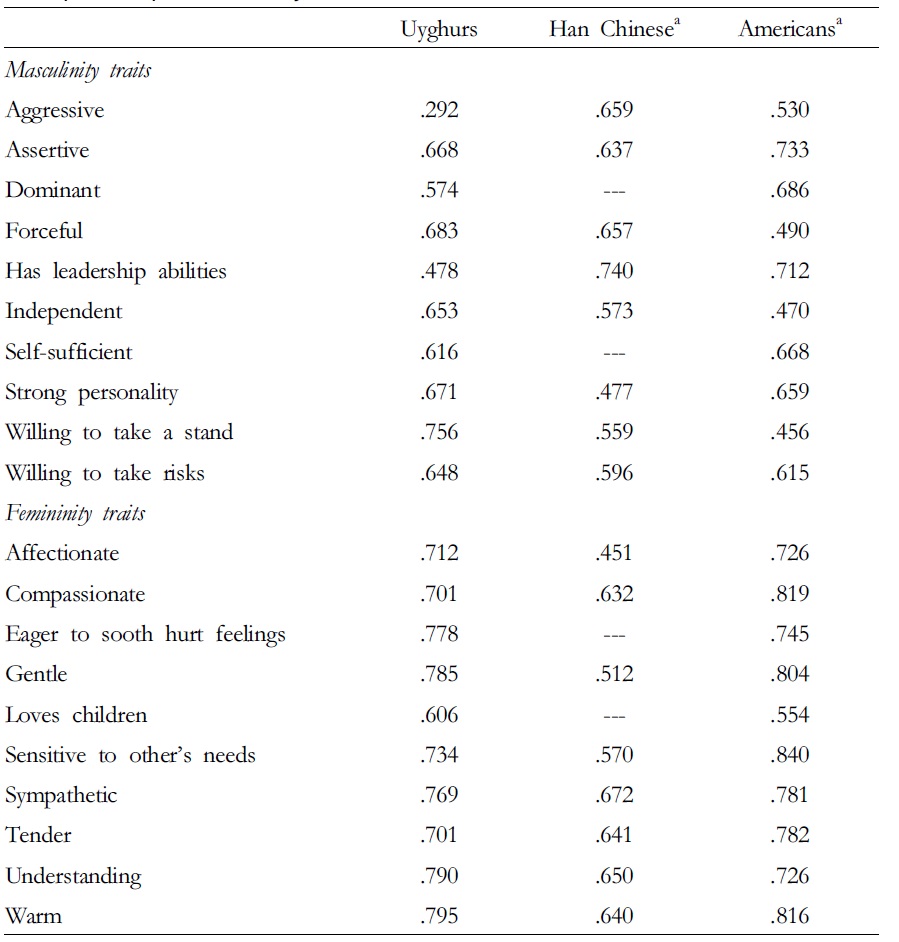

Thus, a principal components analysis with varimax rotation of the 10 M items was performed (Table 7). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin coefficient is .840 (

A principal components analysis with varimax rotation of the 10 F items was also performed. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin coefficient is .902 (

[Table 7] Principal components analyses of masculine and feminine items

Principal components analyses of masculine and feminine items

The first research question of this paper is whether the traits which comprise the masculine and feminine dimensions of the BSRI are valid in Ürümchi, and whether they are valid when tested with a sample drawn from the general population using the PPS sampling method. The Uyghur respondents were not asked to rate the importance of traits for themselves, rather they were asked to rate traits for an ideal man and an ideal woman. Using the same desirability rating scale for the traits and the same criteria by which a trait was considered masculine or feminine for the original instrument (Bem, 1974), it is found that the 10 feminine traits qualifies as feminine and 9 of 10 masculine traits qualifies as masculine in Ürümchi. These findings are consistent with those of Harris (1994), Holt and Ellis (1998), Özkan and Lajunen (2005, p. 104), and other scholars. The Ürümchi study offers support to the BSRI’s application to cultural settings other than North America. In fact, the findings from the Ürümchi study suggests that the BSRI is perhaps more relevant for the Uyghurs than for Americans. This is probably because Uyghur culture stresses traditional gender roles. In comparison, there are movements toward a greater degree of gender egalitarianism in the US, and women’s and men’s roles in American society have changed in a variety of ways, which may affect how Americans perceive the key characteristics of masculinity and femininity (Auster & Ohm, 2000, pp. 499-500). These contrasts may plausibly account for the likelihood that the Uyghurs are more likely than Americans to adhere to traditional gender role expectations when rating desirable traits for masculinity and femininity.

However, the above findings do not tell readers whether the Uyghur men and the Uyghur women stress different masculine and feminine traits. Thus, the second research question is how similar Uyghur men’s ratings are to the Uyghur women’s ratings for the masculine and feminine traits. It is found that there is a reasonable degree of similarity with regard to the highest rated masculine items across genders. There is also a good degree of similarity in rating the feminine scale by the Uyghur men and the Uyghur women. Both the male and the female respondents’ perceptions of an ideal man and an ideal woman were quite gender typed. Moreover, the Uyghur men and women similarly perceived some masculine and feminine items to be the least like what a man should be and to be the least like what a woman should be. The patterns of the desirability ratings arranged in rank seem traditionally gender typed and support the applicability of the BSRI in Ürümchi.

What does the above discussion tell us about gender role expectations among the Uyghurs other than evaluating the validity and usefulness of the BSRI? To partly answer this question, the third question this paper asks is what the most important traits are for masculinity or femininity. It is found that both the Uyghur men and Uyghur women rate “self-sufficient” as the most important trait “for a man”. This item is not among the masculine dimensions of the short form of the BSRI. Yet it is important for Uyghur masculinity because the Chinese government has aggressively promoted labor market reforms after 1978. Large scale unemployment, redundancies, and massive layoffs have affected or threatened the lives and livelihoods of millions of families in China. Workers of minority status have suffered from discrimination in the labor market, which has strengthened the emphasis in Uyghur culture on men’s responsibility for financial provision. There is the need to modify the BSRI before it can be used productively in the social contexts outside North America.

This need can be further illustrated with reference to “aggressive”: it is a main masculine trait in the US context (Auster & Ohm, 2000, p. 506; Blanchard-Fields, Suhrer-Roussel, & Hertzog, 1994, p. 425; Choi, Fuqua, & Newman, 2008, p. 898), yet it is irrelevant for the Uyghurs to define masculinity. In Uyghur culture, aggression is undesirable for both sexes, and open displays of anger to other Uyghurs are not appreciated as a sign of masculinity. Uyghur masculinity seems to be based on a man’s ability to be assertive, independent, and forceful, i.e., on his ability to defend and advance his cause without trespassing on others’ rights and dignity. This partly reflects the collective or communal nature of Uyghur culture. Similarly, “has leadership abilities” is not as a crucial masculine trait in Ürümchi as in the US.

Furthermore, the Uyghur respondents, whether male or female, felt that a combination of masculine and feminine traits is important “for a man”, and this result might reflect the societal changes in values which have occurred in Ürümchi (Clark, 1999; Rudelson, 1997). It is difficult for Uyghur men to be a male chauvinist in Ürümchi nowadays since many Uyghur women have a job and their wages are important in meeting household financial needs. Both the Uyghur men and women are better educated than their parents and appreciate conjugality (Clark, 1999). This may partly explain why they think that “sensitive to other’s needs”, “loves children”, and “understanding”, which are F items, are some of the key masculine dimensions. It seems that a masculine Uyghur man is a responsible provider, a caring husband, and a loving father. This perception reflects the continuity (financial provision) and changes (caring, sensitive, and loving) in Uyghur culture with regard to what an ideal man is. This is similar to the findings reported by Auster & Ohm (2000, p. 523) that in the US, gender differences in self-ratings on the masculinity dimension have been decreasing over time.

Auster and Ohm (2000, pp. 523-524) also report that in the US, masculine traits were seen as desirable for both men and women. But the Uyghur respondents did not think this way. Both the Uyghur men and women defined femininity mainly in terms of affection and expressiveness. This is consistent with virtuous housewifery and good motherhood stressed in Uyghur culture. Uyghur women’s key responsibility is homemaking and childrearing (Zang, 2011). Their paid work has improved their status in the family and society, but it is not a top feminine trait. There is much more continuity in women’s roles than in men’s role in Ürümchi, which may be partly accounted for by the on-going Islamic revival in Xinjiang. Islamic teachings emphasize traditional gender roles and emphasize women’s roles more than men’s roles (Zang, 2008, 2011). The Uyghur women seem to be more likely than the Uyghur men to believe that traditional gender expectations persist in terms of the desirability of particular traits “for a woman”. This is similar to American women when they rated the traits related to femininity (Auster & Ohm, 2000, p. 525).

Finally, Damji and Lee (1995) pointed out that “Researchers who study gender roles often overlook ethnic factors, despite the fact that gender roles vary considerably in different ethnic groups” (p. 216). Peng (2006, pp. 843-844) noted that the studies based on non-Western cultural or ethnic contexts were still few. This paper is the first attempt in the published Western literature to examine the psychometric properties of the BSRI among ethnic minority groups in China. It offers a piece that has been missing in the line of gender role research, strengthening the applicability of the BSRI in different cultural contexts. Equally important, most existing studies have relied on convenient samples drawn from university campuses. It is argued that university students are homogeneous in the tests of the BSRI (Choi & Fuqua, 2003), and that the findings based on undergraduate students may not be “generalizable to the population at large” (Auster & Ohm, 2000, pp. 526-527). This paper is one of the few attempts to examine the validity and usefulness of the BSRI with a scientifically drawn sample. Its findings are relevant for future efforts to test the BSRI with samples drawn from the general population at large or from other ethnic minority groups in China.