The Human Rights Pillars: The State System and the Enlightenment

In this essay human rights encounter Durkheim’s

“The social” will here be seen as structure and culture. A structure is a web of social relations. We are

The human rights tradition carries the imprint of its origin in 17th-18th centuries European history: a

The state system structures the rights and duties of states. One right is the right of war, and one duty is to declare the war in advance; the right that Japan was deprived of in Article 9 of its constitution. States are conceived of as sovereign, conditioned by nothing but themselves, like the construction of individuals in Western Antiquity and Western Modernity-Renaissance; actually in denial of the

The enlightenment is a secular culture removing the divine from its predecessor, christianity: from the economy (Adam Smith; but surviving as an invisible hand); from the human mind (Kant, but surviving as moral consciousness and the stars); from mechanics (Laplace, je n’ai pas besoin de cette hypothèse), from evolution (Darwin), from history (Marx), from individual moral struggle (Freud). Quite some project.

How, then, do the two socials and human rights interlink?

The human rights were embedded in a structure with the state system up front, carrying an enlightenment culture, being a product of its context. But precisely how?

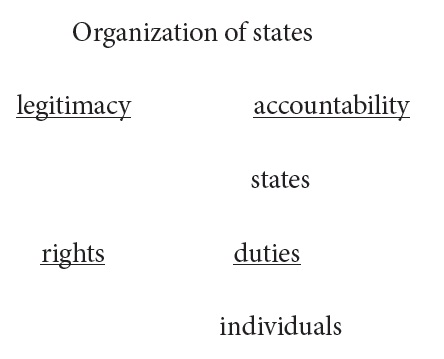

As a triadic

In this triadic structure the state organization gives legitimacy to states who receive the human rights norms by signing and ratifying, in return for states being accountable in human rights terms; and the states guarantee the rights of the individual citizens in return for such citizen duties as paying taxes, military service and respect for the state:

The norm content, their culture, reflected enlightenment secularism. Not only was the divine, as expressed in the Ten Commandments, removed as norm-sender, but also as a source of legitimacy and as the judge holding individuals accountable.

Even non-divine spirituality, attachment to some reality beyond the sum of individuals — like the web of life (buddhist) or the togetherness in the divine (islam) or the membership in a clan or in social harmony (Chinese, Japanese) — is removed.

The human rights culture is one of concreteness, a basic concern being that the thesis “a human right has been/has not been met” can be verified, or at least falsified. There is an implicit behaviorism evident to any eye perusing the 12 December 1948 UD and the 16 December 1966 CP and ESC Covenants the first and second generations respectively. In principle rightsholders have claims on duty-holders, and adjudication is based on holding the empirically observed and non-observed evidence up against the normatively defined right and wrong. The concrete and empirical will then tilt the rights away from the spiritual and mental toward the somatic and behavioral.

The third human rights generation effort to accommodate peace, development and the environment inside a human rights discourse is problematic as these are social level constructs. But Article 28 of the UD may come to the rescue, normalizing to everyone language: Everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration can be fully realized.

1Like the famous Margaret Thatcher thesis that there is no such thing as society, only individuals; thereby in principle denying the basis of sociology as a science. 2Very problematic, indeed, for god-states like the USA, Israel and Iran, accountable to that higher authority only; in the case of the US a closely “under God” that there is hardly space for any UN Charter or International Bill of Human Rights in-between. 3See Galtung and MacQueen (2008), see www.transcend.org/tup

Globalization Challenging the Pillars

The two-three centuries old context for the human rights tradition has in the meantime changed dramatically. Both pillars are shaking under the impact of globalization processes toward an increasingly borderless and an increasingly shrinking world. “Borderless” refers to the gradual erosion of the borders between states, and “shrinking” to all human categories, any other, coming closer, even so close that such borders as fault-lines, between genders and generations, classes and nations, are also either erased,

For eyes trained on territorial borders only it may look as if we are moving toward a one state-one nation world; the single state being the world, and the single nation humanity. In other words, a world government in a world without major fault-lines of any kind, only individuals, many, diverse, but borderless, and with the three generations of human rights as constitution.

Concretely, states — except the big ones beyond 100 million — are yielding in salience to such actors as local authorities (LAs), nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), transnational corporations (TNCs), regions, and at the global level the UN.

And secular I-culture enlightenment is competing with religions, spirituality, and we-cultures. The idea of Western secularism becoming a universal world view, like in Matt. 28:18-20 is fading. Structures and cultures are dialectic; there are forces and counter-forces. Surprising only to linearists.

The Social Is Changing; so also the Human Rights?

We start with the hypothesis of the fading state system.

There are two major problems. First, do states really have the power, resources and legitimacy to implement human rights if they so want? And second, given the CP and ESC records of many states, particularly the bigger ones, is it obvious that they so want? If incapable, or unwilling, or both, do some states still serve a useful purpose in the human rights construction?

Or, could other actors, like regions, be more useful, given the mobility and cultural shocks mentioned? How about regions — European, African, South Asian, Southeast Asian, and the coming Latin American, Islamic, East Asian and possibly Russian?

Beyond that, could we possibly imagine another approach, in fact broadening all levels in the triadic construction?

To start at the top: the UN has been very skilful in accommodating nonstate actors as carriers of world views “in consultative capacity”. Sooner or later a Security Council will reflect the regions, not like today giving the EU two vetoes and the others none. There are platforms for NGOs. The TNCs are brought in under the heading of social compacts (the LAs are absent, however). For a human rights council to consult with all of them, even bringing them in, should not be too complicated.

At the middle level: why not take the whole catalogue of rights and add non-state to state actors as duty-holders, adding not only regions but also NGOs-TNCs-LAs? Europe as a region is both norm-sender, duty-holder, sender of legitimacy and receiver of accountability. That formula could be generalized to other regions, some may be ready, some not, under the aegis of the UN.

At the bottom level: adding collective to individual rights-holders, to accommodate we-culture concerns.

These processes are evolving today, with the European region, the NGO Amnesty International, and the social compact approach up front. The human rights discourse accommodates them all up to some point, which in itself is no small achievement.

But with structures changing, meanings of human rights will also change. Late 18th century human rights delivered a fragmented, individualized citizenry to the state, against payment in human rights currency, and with the right for the state to exact payback in obedience currency, ultimately their life, serving the wars promoted by the state. A good deal?

With duty-holders more dispersed the loyalty-subservience of the rightsholders will not be the same. Loyalties, payback obligations, felt or real, will also be dispersed. From a world with a fragmented system of states with fragmented citizenries a more pluralistic human rights structure should promote a more complex web of rights and duties. More entropy, more peace.

Adding collective rights will increase this complexity. Take the three examples of possible “Asian” collective rights:

Compare the human rights tradition to a classical family, here a little idealized, but far from atypical. There are one or a few breadwinners, not necessarily male, who contribute more materially than they receive. There are those very young or very old who receive more than they contribute. The setting provides for continuous and contiguous satisfaction of many basic needs. There is a master of distribution, usually the mother-wife, apportioning to the family members according to need more than according to contribution. And all of this carried by a sense of family togetherness and family sharing.

The comment is, of course, that the internal we-culture of the family comes to nothing when no bread can be earned; then they need security nets internal and external to the family. But the basic point is that in a reasonably typical family meeting the needs of all is internalized as a culture, and institutionalized in the structure. Not doing so will lead to bad internal feelings and negative sanctions. Members of a family generally want do to each other what they have to do.

And in that lies the crux of the matter. Let us say we are searching for a structure and culture of human rights so that rights are met because dutyholders want to do what they have to do, must do. Or, do what they must do because they want do so, as the song goes, doing what comes naturally.

If conceived of as a part of the legal traditio the focus is on negative institutionalization, punishing the duty-holder for not exercising the duty, lamenting how this genius human rights bridge between domestic and international law falls short because it is not enforceable in an anarchic world. The legal tradition is punishment oriented; the socio-anthropological tradition is equally or more internalization oriented.

Norms are rooted inside us, not only communicated from the outside as reward and punishment. But one condition for this to happen is that the norms,

However, when the twin assumptions of secularism and individualism are not satisfied problems arise. Take the buddhist case. There is a deep spirituality seeing the web of relations between all sentient life, past-presentfuture, as more real than the individual manifestations of life. This means that how one relates is more important than who one is. Relations matter more than attributes. “I relate, hence I am” overshadows the individualistic “I think, hence I am”, and even more so if those thoughts are supposed to be cartesian only.

In some buddhisms the ethical budget is collective: what my “I” has done of good comes to my near others as a merit because they inspired me. And conversely, whatever that “I” has done of bad comes to that “we” as a demerit because of acts of omission: they should have warned me, stood by me, helped me in that critical moment. My act of commission was contingent on their acts of omission.

The human rights implication is the right to relate. But in an atomizing postmodern social order with high loneliness that may be impossible. A social crime; some kind of genocide.

Let us hold the islamic social — with abrahamic roots like judaism and christianity but with more distance to secularism and individualism — up against human rights.

Objection: meeting the right is an end that can be met by many means. However, if the means also become autotelic ends, then sharing, like togetherness, becomes a right, not only a duty, moving up in the means-ends hierarchy. To be enshrined.

Pillar No. 5, the

Tariq Ramadan (2010), in

4Which means one out four humans, there being now 1,570 million muslims in the world (Stavanger Aftenblad, 2009/9/16).

The Right to Life - and to the Afterlife: A Note

The human rights tradition includes the right to life. It would have been more credible had there been a right to live in a social and world order where everything is done to solve conflicts by peaceful means before they turn violent.

But the human rights tradition does not include the basic human concern of all times: our body has only a finite lease on life. Many are the formulas to extend that lease beyond the death of the body into an afterlife, like the christian promise of salvation for an eternal afterlife, on the condition of the right faith and-or deeds. The enlightenment spirit would, and should, certainly exclude any right to salvation as something beyond the capacity of any duty-holding state. But it is not beyond the capacity of a duty-holding state to make available concrete factors seen as necessary conditions for access to an afterlife to the believers, like the places of worship. confession etc. Referring to the November 25 2009 Swiss referendum on forbidding minarets the argument might be that these institutions should be visible, maybe also audible (the mosque muezzin, the church bells). For the believer there is much at stake. Freedom of faith assumes freedom of practice.

If afterlife is seen in terms of progeny, then the rights of a clan as social actor enters. If afterlife is contingent on being member of a group with a collective ethical budget, then institutionalized isolation has to be avoided. All of this is within the capabilities of relevant duty-holders if they are not limited to states as organizations.

The enlightenment threw out the divine, and in that process also came close to negating the spiritual. But the spiritual has material foundations, and their protection is a human right.

Human Rights Meeting Social Science: A note

There is a huge problem here. I have built this essay around the idea that the human rights tradition was resting on two pillars, the state system and the enlightenment, both of them challenged by a vast array of interconnected processes we refer to as globalization. I have tried to make the point that human rights will have to change, at least bend; or else crack. They will not get out of this encounter untouched.

Others hailing from that vast intellectual continent social sciences, including law and history, may see this wholly or partly differently.

The problem with the social sciences is that they are also the children of the state system and the enlightenment. The unit they address, with the honorable exception of anthropology, is the country-state: sociology, economics, political science (the German

“Social” means state, it seems. And “science” means empiricism, even behaviorism, depriving human beings of their inner essence, the spiritual ability not only to see themselves but to transcend what they see. Which they do again and again, but so much social science tries to freeze them in static, non-contradictory, laws called findings.

The unavoidable conclusion from this analysis is that the social sciences suffer from the same deficits as the human rights: They are all children of the same union of the structure of the state system with the culture of enlightenment. The problem is whether they are capable not only of suggesting remedies but even of analyzing deficits from which they themselves are suffering. An objection might be that if experienced as deficits they could be particularly capable.

However that may be, the peace research discourse is an effort to elaborate epistemologies capable of accommodating such problems. A key term is “trans”, like in transnational, translevel, and transdisciplinary

However, there is a deeper level than “trans”, like an epistemology of dialectic holism. The world is, indeed, a

Human rights as they emerged are not forever, nor is “the social”, any social, nor the sciences to come to grips with the social. Hence this essay, as an indication of where the current dialectics may take us. Yield or break, like the famous cherry tree branch overloaded with wet snow. Adapt or die. Better the former, particularly with something so valuable as human rights.

5See Galtung (2008), www.transcend.org/tup.